Abstract

Respiratory burst oxidase homologs (Rboh) genes is essential for synthesizing reactive oxygen species, which play a crucial role in environmental stress response. The Rboh gene family has been studied in model plants such as Arabidopsis. Nevertheless, Rboh remained largely unexplored in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Here, we performed characterization of the Rboh genes family in rice (OsRboh) under Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo), salicylic acid (SA), and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatments. Nine OsRboh genes were retrieved distributed across six chromosomes (1, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12).These genes vary in amino acid sequence length (728–1034), isoelectric point (9.05–9.84), and molecular weight (8.341–115.014 kDa). Analysis of gene structure, motifs and conserved domains showed that OsRboh genes have similar protein sequences and functions. The promoter region of OsRboh genes was found to contain mainly cis-acting elements associated with light, jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), and SA responsiveness. Predictions of functional protein–protein interaction showed that OsRboh genes were associated with MAPK signaling, plant-pathogen interaction, and other mRNA surveillance pathways. Prediction of miRNA targets and post-translational modification sites indicated that OsRboh genes may be regulated by miRNA and protein phosphorylation. Phylogenetic analysis showed that OsRboh genes were distributed into 7 clusters. Furthermore, 9 OsRboh genes were differentially expressed in different tissues (roots, stems, and leaves). OsRbohA, OsRbohB, and OsRbohD are significant genes in rice defense responses, showing unique and increased expression profiles under (Xoo-PXO99), (MeJA), and (SA) treatments. These genes important function in triggering defense mechanisms is further stressed by the high (> 20-fold) changes in expression they exhibit under these treatments. These findings enhance our understanding of rice OsRboh genes functions and contribute to stress tolerance improvement strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The respiratory burst oxidase homologs (Rboh) are crucial for the synthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are important for the development, growth, and resistance of plants to biotic as well as abiotic stresses1. ROS are signaling molecules that contain singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and a hydroxyl radical (HO−) are significant signaling molecules in living beings2. Plants in their natural habitats release low amounts of ROS to facilitate regular growth and metabolism. However, ROS production increases when plants are exposed to most if not all, environmental stress3,4. In the stressful ROS environment, primarily, H2O2 functions as a signaling molecule and carries out programmed cell death5. Rboh, another name for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (NOXs), are the main enzymes that produce ROS6. The first Rboh gene was discovered in rice, which was a significant breakthrough in the study of plant oxidative stress responses7. Rboh genes, which are components of the plasma membrane redox system, transfer electrons from intracellular NADPH to oxygen, generating O₂⁻ that is subsequently converted into other ROS, including H₂O₂8. Structurally, Rboh proteins are characterized by two EF-hand motifs in the N-terminal region, which are involved in calcium binding, and a C-terminal region containing six transmembrane segments and functional oxidase domains9. These proteins are homologous to gp91phox, the catalytically active subunit of the NADPH oxidase complex in mammalian phagocytes10,11.

The structural and functional characterization of Rboh proteins provided important insights into their role in cellular signaling and stress responses12. Earlier studies revealed that the C-terminal of Rboh proteins contains two heme groups, six trans-membrane core sections, cytosolic flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and NADPH binding domains13. In contrast, Rbohs have the N-terminals but have two EF-hands11. Characteristic NADPH oxidases have four conserved domains:NAD_binding_6, FAD_binding_8, NADPH_Ox, and Ferric_reduct14. These findings demonstrated the evolutionary conservation of NADPH oxidases across species.The AtRbohs in Arabidopsis, have similar structures, such as two EF chiral structures that bind to Ca2+ in the N-terminal region13. The Rboh genes was found in several plants, including tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.)15. However, Rboh family members have diverse physiological roles, including vigorous growth and metabolism, stress response, and phytohormone regulation16. Further, ten Rboh genes were found in Arabidopsis13, nine in apples17, seven in grapes18, fourteen in Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)19, nine in rice18, and twenty-six in upland cotton20. Additionally, seven Rboh genes were discovered in strawberries21, seven in jatropha22, eight in pepper23, eight in cassava24, and fourteen in rape seed25 has allowed for a deeper understanding of their roles in growth, metabolism, and stress resistance. These findings have highlighted that Rboh genes are not only involved in biotic stress responses but also regulate phytohormones, increasing their importance in plant biology26. In Arabidopsis, specific Rboh genes such as AtRbohD and AtRbohF are ubiquitously expressed, while others, like AtRbohH and AtRbohJ, are more tissue-specific, being expressed predominantly in pollen and stamens13. Although CaRbohC, CaRbohF, and CaRbohG genes were weakly expressed in pepper, the majority of CaRboh genes (CaRbohA, CaRbohB, and CaRbohD) were highly expressed in all tissues23. In C. sinensis, the genome has identified seven Rboh genes (CsRbohA-CsRbohG). The involvement of the CsRbohD gene in the response to cold stress was demonstrated by functional and physiological analyses and five of these genes were found to be temperature-responsive1. Furthermore, it is well known that other plants display this variable tissue expression of Rboh genes19. In biotic stresses, Rboh-dependent ROS help plants fight back by making cell walls stronger, helping with signal transduction, and playing important roles in different tissues and protecting them from pathogens9,27. Rice is the most important food crop across the world28,29. Rice, being one of the most important food crops globally, faces significant yield losses due to diseases caused by pathogens like Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae and Magnaporthe oryzae. The involvement of Rboh genes in the plant defense mechanisms against these pathogens has made rice an important model for studying Rboh gene function. Research on OsRboh genes in rice has revealed that these genes are expressed constitutively in various tissues such as calli, roots, shoots, and leaves, with some genes like OsRbohD and OsRbohH showing more specific expression patterns30. Additionally OsRbohB is involved in ROS generation and abscisic acid (ABA) signal transduction31.

Phytohormones, including (ABA), (JA) and (SA) are play essential roles in regulating plant responses to environmental stress32. Rboh genes have been revealed to interact with these hormones, influencing plant development and stress resistance. For example, the OsRbohB mutant in rice has altered stomatal dynamics and decreased drought resistance, indicating that Rboh genes are closely related to hormonal regulation and stress response pathways. In rice, OsRbohA and OsRbohE33 and OsRbohB34 are involved in immune responses20. These findings highlight the significance of Rboh genes in coordinating the plant defense strategies and metabolic adaptations to a variety of environmental stresses35.These findings suggest that Rboh genes are essential and play a variety of functional processes in multiple tissues. This study aims to characterize the OsRboh gene family in rice, specifically analyzing nine OsRboh genes (OsRbohA to OsRbohI) retrieved from the most recent rice genome annotation database (RGAP 6.1). We investigate their expression in different rice tissues and under treatments with (SA), (MeJA), and (Xoo), to understand their roles in biotic and abiotic stress responses. Additionally, we compare their physicochemical properties, chromosomal locations, conserved domains, and evolutionary relationships to homologs in other monocots and dicots.

Material and methods

The physicochemical properties and chromosomal distribution and subcellular localization of OsRboh genes

To obtain the physiological characteristics and chromosomal distribution of nine OsRboh genes in rice, the gene sequences and annotations were retrieved from the Rice Genome Annotation Project (RGAP) database (http://rice.uga.edu/)36. The Expasy ProtParam program (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/)37, was used to examine the protein molecular weight (kDa), isoelectric point (pI), instability index (II), aliphatic index, and overall average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) of OsRboh genes. Chromosomal distribution of OsRboh genes was visualized using MapChart (https://www.wur.nl/en/show/mapchart.htm) software which displayed the start and end positions of the genes on the rice chromosomes38. The online bioinformatics tool WOLFSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/)39 was used to predict the subcellular localization of the OsRboh genes.

Motif, conserved domain, and gene structure analysis of the OsRboh genes family

The motif of OsRboh genes was analyzed using MEME Suite v5.5.2 (https://meme-suite.org/)40 and TBtools using the protein sequences of OsRboh genes. The motif number was set to 10, with all other parameters left at default. Conserved domain analysis of the OsRboh gene family was performed using the NCBI (Conserved Domain) CD Search tool. The gene structures of the OsRboh genes were analyzed using the GSDS server (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/)41 based on coding sequences retrieved from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/)42.

Analysis of cis-acting elements in OsRboh genes

In order to understand the regulatory elements of the nine OsRboh genes, the 1.5 bp upstream region before the translation start site of each OsRboh genes sequence was obtained using the Phytozome (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/) website42. The cis-acting elements were analyzed by the online website PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/), the analysis results were submitted to TBtools software for visualization43 and a graph illustrating the distribution of cis-elements in OsRboh genes was created in Microsoft Word.

Analysis of function and protein–protein interaction (PPI)

Protein interaction network investigations were conducted with STRING v9.1 (http://string-db.org/)44. The STRING database retrieves both the functional and physical interactions among proteins. A medium confidence score ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 was used to examine functional interactions. Therefore, interactions with scores of less than 0.4, from 0.4 to 0.7, and more than 0.7 are considered to have low, high, or maximum confidence, respectively. A total of 10, 20, and 50 interactors were the maximum number of interactors that could be found. Each of the choices had equivalent score of confidence that ranged between 0.865 to 0.99, 0.8 to 0.99, and 0.659 to 0.99, in that order.

Prediction of OsRboh genes phosphorylation and miRNA target sites

The psRNATarget program was applied to predict the miRNA targets of OsRboh genes (https://www.zhaolab.org/psRNATarget/) using the standard parameters45. The PmiREN database (https://www.pmiren.com/) provided the mature microRNA sequences of rice genes46. The phosphorylation sites47 were predicted with the online tool Musite (http://musite.net/) at a 95% specificity level. A model rice was selected to predict phosphorylating serine (S) threonine (T) Tyrosine (Y) residues.

Evolutionary relationship analysis of OsRboh genes and 8 other species

OsRboh genes evolutionary relationships were studied in nine plant species: Oryza sativa, Arabidopsis thaliana, Zea mays, Saccharum officinarum, Hordeum vulgare, Sorghum bicolor, Triticum aestivum, Setaria italica, and Brachypodium distachyon. The sequences for these species were obtained from Phytozome. MEGA11 was used for multiple sequence alignments, and the neighbor-joining method was used to construct a phylogenetic tree48. To evaluate the tree reliability, a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replications was performed using the P-distance substitution model.

Plant material and treatments

Germinated wild TP309 rice plantlets were grown in pots at 30 °C/28 °C with a 14 h/10 h day/night cycle. One-month-old rice plants, including roots, stems, and leaves, were collected for analysis. For hormonal treatments the rice plants with four leaves were sprayed with 1 mmol/L (SA) and 0.1 mmol/L (MeJA), while control plants were sprayed with deionized water (ddH2O). Leaf samples were collected at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h after treatment. For bacterial Inoculation the (Xoo) strain PXO99 was cultured on solid PSA medium containing 1% (w/v) peptone, 1% (w/v) sucrose, 0.1% (w/v) glutamic acid, and 1.5% (w/v) bacto agar, adjusted to pH 7.0. Bacterial cultures were grown at 28 °C for 2 days, after which the bacteria were harvested and suspended in sterile distilled water to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5–0.6, corresponding to approximately 108 CFU/mL. Inoculation was performed using the leaf-clipping method49. The second leaf of four-leaf-stage rice plants was clipped using sterilized scissors, which were first dipped into the Xoo suspension. The leaf tip (approximately 4–5 cm) was removed, and 50 µL of the bacterial suspension was applied to the cut surface. Control plants were inoculated with 50 µL of sterile distilled water. Following inoculation and hormone treatments, all leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for further analysis.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China, DP305) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of isolated RNA were determined using 1.5% agarose, gel electrophoresis, and NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The cDNA synthesis was performed according to the instructions of RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time qPCR analysis was performed using SYBR Green Mix PCR Kit with three technical replicates for each biological sample. The thermal cycling program was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 58 °C for 25 s, extension at 95 °C for 15 s, plate reading at each step, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The 2−ΔΔCT method [ΔΔCT = (Ct target gene − CtGAPDH)] was used to determine each mRNA relative expression50. As an internal reference gene, the OsGAPDH was used. List of the primer sequences used in real-time PCR Table S1.

Statistical analysis

We used the 2−ΔΔCT method to determine relative expression data and used Excel 2010 software for statistical analysis. The Values are presented as mean ± SD. We used t-test in GraphPad Prism v.8.5.0 to assess differences between groups p value (*: < 0.05, **: < 0.01, ****: < 0.0001, ns: not significant).

Results

Physiological properties, chromosomal distribution, and subcellular localization of OsRboh genes in rice

Nine OsRboh genes were retrieved in the rice genomic annotation database using Expasy ProtParam bioinformatics tools. These nine OsRboh genes are distributed through six chromosomes out of twelve chromosomes (Fig. 1). Chromosome1 contains three Rboh genes (OsRbohA, OsRbohB, and OsRbohE). Chromosome5 contained OsRbohC and OsRbohD. Chromosome 8, 9, 11, and 12 contained OsRbohF, OsRbohG, OsRbohI, and OsRbohH, respectively (Fig. 1). The amino acid sequence length of OsRboh proteins varied from 728 (OsRbohA) to 1034 (OsRbohF), while the isoelectric point varied from 9.05 (OsRbohA) to 9.84 (OsRbohF). Additionally, the relative molecular weight varied from 8.341 to 115.014 kilodaltons (kDa) (Table 1). The instability index showed that OsRbohB was the most unstable protein. The average GRAVY values of all OsRboh proteins were found to be less than zero, indicating that these proteins were hydrophilic overall. Subcellular localization prediction with WOLFSORT showed that OsRboh proteins were restricted on the plasma membrane.

Analysis of OsRboh genes structure, motif, conserved domain

The structures, motifs and conserved domains of nine OsRboh genes were analyzed using TBtools program. 10 motifs were predicted throughout the OsRboh genes (Fig. 2a). The OsRboh genes in each cluster shared similar motif distributions except motif 8, which is absent in the OsRbohF gene. The motifs are distributed consistently, suggesting that the OsRboh gene family members have highly conserved protein sequences, indicating similar functions. The OsRboh genes shows various conserved domains (Fig. 2b). All OsRboh genes have the NAD_binding_1 at their N terminal. In addition, OsRbohH members contain the EF-hand_7 domain. EF-hand_7 are predicted as a conserved EF-hand domain associated with calcium ion binding. However, OsRbohD, OsRbohE, and OsRbohI contain EF-hand_1. Except for OsRbohE and OsRbohF, other OsRboh gene family members contain Cytocrome_b_N. All OsRboh genes have a ferredoxin reductase (FNR) domain. The FNR domain is involved in the electron transfer process of the photosystem51. The structural features of OsRboh genes and exon–intron structures was noted based on their evolutionary relationship (Fig. 2c). Although intron length and position varied, most of them had phase distributions that are similar. Most OsRboh genes contained 10 and 15 exons in the coding DNA sequence (CDS) with OsRbohA, OsRbohE, and OsRbohF containing 12 introns. In addition, OsRbohC and OsRbohG contained 13 introns, OsRbohB 11, OsRbohD 14, OsRbohH 10, and OsRbohI 9 restricted introns. Overall, the OsRboh genes of the same subfamily have shown different gene structures, indicating that they have a close evolutionary relationship.

The evolutionary relationships of motif, conserved domain, and gene structure. MEGA 11 was used to generate the phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method. (a) Examining 10 OsRboh genes motifs. The distinct colored rectangular box represents every motif. (b) OsRboh genes conserved domain distribution. Different color blocks indicate the conserved domains in the OsRboh proteins (c) Yellow, gray, and green rectangles represent gene structures called introns, exons, and untranslated regions (UTRs), respectively.

Function prediction of cis-acting elements of OsRboh genes and different types of cis-acting elements in the promoter region of OsRboh genes

Cis-acting elements are most significant for regulating the expression of genes52. The PlantCARE database was applied to extract the 1500 (bp) region upstream of the start codon of the OsRboh genes for cis-acting element analysis and to predict the potential function of the OsRboh genes43. The results displayed that OsRboh genes contain numerous cis-acting elements (Fig. 3a). A total of thirteen cis-acting elements were screened, including six stress responsiveness elements (low-temperature, light, anaerobic-induction, wound, drought-inducibility, and defense Stress responsiveness), two development regulation elements (Meristem expressions and seed-specific regulation), and five hormone elements MeJA gibberellin, abscisic acid, auxin, and salicylic acid responsiveness). Among the cis-acting elements, those related to light response, methyl jasmonate (MeJA) response, abscisic acid (ABA) response, and salicylic acid (SA) response were notably enriched in the promoters of most OsRboh genes. The graphical representation of these findings is shown in (Fig. 3b).

Promoter region of OsRboh genes (bp). (a) The rectangles that change color represent cis-acting elements. The black lines indicate the OsRboh genes promoter’s region size. (b) Each color in the bar graph represents a distinct response category and shows the quantity and kinds of elements linked to different hormone responses and other regulatory processes across various Rboh genes.

Predictions of functional protein–protein interaction

A combined interaction network of nine OsRboh genes has been generated to identify the interactions between the OsRboh and other proteins within the relevant plant species (Fig. 4). The relationship between OsRboh and other proteins in related plant species has been identified through molecular function and cellular component analysis. A network model involving 9 OsRboh proteins was generated using the STRING database. The Physiological and functional interactions of OsRboh proteins. A network model was generated using the STRING database involving nine OsRboh proteins, which have 50 interactors and indicate possible interacting partners in the evidence view, 57 nodes (proteins), and 420 edges (interactions) with statistical significance (P- values) ranging from 1.0 to 1653. The KEGG database showed that they were involved in MAPK signaling, plant-pathogen interaction, and mRNA surveillance pathways. OsRbohC, OsRbohE, OsRbohG, OsRbohH, and OsRbohI interacted similarly with CDPK (calcium-dependent protein kinase) in MAPK signaling. OsRbohD and OsRbohF were involved in NADPH oxidase H2O2 formation activity.

Analysis of OsRboh genes phosphorylation and miRNA target sites

Protein post-translational modification (PTM), regulates several vital biological processes, such as membrane transport, cell signaling, metabolism, and differentiation54. The protein sequence analysis revealed that OsRboh genes contained conserved phosphorylation sites, such as serine, threonine, and tyrosine (Table 2). Most phosphorylation sites of OsRboh genes were observed in OsRbohC, and the fewest sites in OsRbohD. Most of the possible phosphorylation sites are located in the N-terminal region upstream of the EF-hands. As an instance, OsRbohC serine residues correspond to S-7, S-9, S-22, S-32, S-42, S-112, and S-120 in the same sites: OsRbohB-32, OsRbohE-9, OsRbohF-120, OsRbohG-22, and OsRbohH-7, 42, 112, respectively. The equivalent OsRbohD serine residue S-5 was also conserved in OsRbohE in the same sites. MicroRNAs are important for plant growth, signal transduction, and defense against biotic and abiotic stresses55. The psRNATarget was used with default parameters to predict the target miRNA of OsRboh genes. The rice genome was used as query sequences. We selected the small RNA/target sites and set a maximum expectation value of 5. The prediction displayed that the OsRbohD targets mi11339 and mi11343 families with the minimum expectation value of 1. The OsRbohA targets the mi11339 family and the OsRbohH targets the miR531 family with the minimum expectations value of 2.5. While OsRbohF targets the miR2228 family, OsRbohG targets the miR5799 and OsRbohI targets the miR2275 gene family with a confidence value of 3. Additionally, OsRbohE targets the miR171 family; OsRbohC targets miR1850, and miR5519 families; and OsRbohB targets the miR5819 family with the expectation value of 3.5 (Table S2).

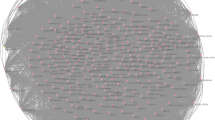

Evolutionary relationship of OsRboh genes and other plant species

125 Rboh genes, including 9 Oryza sativa, 10 Arabidopsis_thaliana, 15 Zea mays, 43 Saccharum officinarum, 8 Hordeum vulgare, 10 Sorghum bicolor, 8 Triticum aestivum, 13 Setaria italic and 9 Brachypodium distachyon were used to infer a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5a). The Rboh members were clustered into seven groups and the numbers of Rboh genes family were provided in (Fig. 5b). OsRbohG and OsRbohF are both clustered in Group 3. Group 4 contained OsRbohD and OsRbohE. OsRbohI belongs to Group 5. Group 6 includes OsRbohA and OsRbohB; however, Group 7 contained OsRbohC and OsRbohH. No OsRboh members belonged to Groups 1 and 2. The absence of OsRboh genes in Groups 1 and 2 is likely due to the evolutionary variance and functional change specific to Oryza sativa. These evolutionary routes might have led to a distribution of Rboh genes that reveals the unique physiological and environmental adaptations of rice, resulting in OsRboh genes in Groups 3 to 7 but not in Groups 1 and 211. In Group 2, Arabidopsis (a eudicot) and monocots both descended from a common angiosperm ancestor, but they diverged from each other very early in angiosperm evolution, long before Arabidopsis separated from other eudicot lineages56.

Phylogenetic trees (a) Alignment of Rboh genes in Oryza sativa, Arabidopsis thaliana, Zea mays, Saccharum officinarum,Hordeum vulgare, Sorghum bicolor, Triticum aestivum, Setaria italic and Brachypodium distachyon using MEGA-11. The P distance substitution model and neighbor-joining method were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap values were set to 1000. Phylogenetic tree was visualized using iTol online (b) Seven groups are displayed in various colors. OsRboh genes sequence counts groups 3–7.

OsRboh genes expression in diverse tissues

The qRT-PCR analysis revealed significant differences in OsRboh gene expression levels across rice tissues (roots, stems, and leaves) at various growth stages. OsRbohA and OsRbohE were predominantly and significant expressed in the root, whereas OsRbohC and OsRbohD were more expressed in the leaf and stem as compared to the root, showing statistical significance. On the other hand, OsRbohF, OsRbohH, and OsRbohI exhibited relatively lower and diverse expression across tissues. These findings highlight the tissue-specific expression patterns of OsRboh genes, implying that they might play key functions in rice development.

Analysis of OsRboh genes expression patterns under Xoo, MeJA, and SA treatments

The rice cultivar TP309 was treated with (SA), (MeJA), and (Xoo-PX099) under stress conditions. We exposed 4–5 leaf stage rice seedlings to simulated conditions at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h. Subsequently, the expression profile of OsRboh genes was examined through qRT-PCR (Fig. 7). Under (SA) treatment, OsRbohA, OsRbohC, and OsRbohH genes show upregulation. While the expression levels increased in OsRbohA and OsRbohC (8 ~ sevenfold) times higher than at 0 h and no significant change individually. On the other hand, the remaining OsRboh genes showed varying degrees of downregulation at 0 h, 3 h, and 6 h. After (MeJA) treatment, the expression levels of OsRbohB, OsRbohE, and OsRbohI were upregulated after post-treatments, and the other six genes showed downregulation at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h. Notably, OsRbohB was significantly increased, and the expression level was over (~ sevenfold) times more than that of 0 h. While the same time OsRbohG expression increased (~ fivefold) higher than at 0 h, there was significant change in fold. During (Xoo- PXO99) strain inoculation within 12 h OsRbohD, OsRbohE, and OsRbohF were upregulated. Conversely, the remaining OsRboh genes showed downregulation at 0 h, 3 h, and 6 h in response to Xoo induction post inoculation. The expression levels of OsRbohD and OsRbohF showed the upregulation, and the relative fold is about (20–16-fold) times more than that of 0 h and also no significant fold change. These results showed that OsRbohA, OsRbohB, and OsRbohD are highly expressed after treatments with (JA), (SA), and (Xoo-PXO99). OsRbohD and OsRbohH may be more closely associated with (SA) induction because their transcript levels were only elevated under (SA) treatment. OsRbohE and OsRbohF expression levels may not be shown in SA- and MeJA-mediated defense because their expressions remained undetected.

Discussion

Rboh genes are essential for (ROS), and these contribute significantly to the defense mechanism beside biotic and abiotic stresses57. The role of the OsRboh genes in the rice plants stress behaviour and pattern of its expression in the plant immune response are still unclear although its primary role has been established58. In this study, we identified and characterized nine members of the OsRboh gene family in the rice genome (Table 1). The OsRboh genes were distributed on 6 chromosomes out of 12 (chr1, chr5, chr8, chr9, chr11, chr12), with the maximum number of genes found on chr1 (Fig. 1). According to the subcellular localization estimation, the membrane of plasma is bound to nine OsRboh proteins., as described previously20,23, indicating a possible function for Rboh in controlling the production of ROS. Notably, in Grape (Vitis vinifera L.), a few Rboh genes, such as VvrbohA, VvrbohC1, and VvrbohD, suggest similar functions to other plant homologs. These proteins are predicted to be found in the plasma membrane18.

The OsRboh genes in each cluster shared similar motif distributions except motif 8, which is absent in the OsRbohF gene. The motifs are distributed consistently in Rboh genes (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the OsRboh family members contain a highly conserved domain and similar functions24. Nine OsRboh genes have the NAD_binding_1 at their N terminal. The NAD_binding_1 domain is likely involved in binding to NAD, which is important for the enzymatic activity of the OsRboh proteins59. Additionally, OsRbohH members contain the EF-hand_7 domain. EF-hand_7 is predicted to be a conserved EF-hand domain associated with calcium ion binding. However, OsRbohD, OsRbohE, and OsRbohI comprise EF-hand_1. Except for OsRbohE and OsRbohF, other OsRboh genes family members contain Cytocrome_b_N. All OsRboh genes have the Ferredoxin reductase (FNR) domain and MPS2 domain (Fig. 2b). In Solanum melongena L. all eight SmRboh genes have the domain NADPH_Ox Ferric_reduct is not present in SmRbohE2, but NAD_binding_6 and the Ferric_reduct domain are absent from SmRbohE160. Moreover, ZmRBOHs possess EFh and EF-hand_7. The functions of these conserved domains are different11. They are very essential for the structure, function, and regulation of the OsRboh proteins, which are important for plant defense responses and various developmental processes61, according to our analysis of the OsRboh gene structures. The coding DNA sequence (CDS) of most Rboh genes comprised 10 to 15 exons (Fig. 2c). Although OsRbohC and OsRbohG contained 13 introns, OsRbohB 11, OsRbohD 14, OsRbohH 10, and OsRbohI 9 restricted introns, OsRbohA, OsRbohE, and OsRbohF confined 12 introns. Overall, distinct gene structures have been observed in the OsRboh genes that belong to the same subfamily, indicating their strong evolutionary links. The highly varied distribution of intronic regions compared to exonic sequences in Rboh genes, the understanding of structural variation in these genes and their splicing variations indicates to significant genomic changes during the evolutionary history52.

The promoter regions of the OsRboh genes exhibited various cis-acting elements, as identified through plantCARE (Fig. 3a). The components were divided into three functional groups: hormone response, stress response, and development regulation42. In this study, Six stress responsiveness components were chosen out of a total of thirteen illustrative cis-acting elements: low-temperature, light, anaerobic-induction, wound, drought-inducibility, and defense Stress responsiveness; two development regulation elements: Meristem expressions and seed-specific regulation; and five hormone elements: MeJA gibberellin, abscisic acid, auxin, and salicylic acid responsiveness. The graphical representation of these findings is shown in (Fig. 3b). Previous studies suggested that Rboh genes involve several physiological processes, such as hormone silencing, biotic and abiotic responses, and development62. For example, ABA can increase tomato tolerance, improve Rboh enzyme activity, and induce the expression of the SiRboh1 gene63. Jasmonate acid compounds (JA) are significant stress signaling molecules that control the antioxidant enzyme system of the plant as well as Rboh activity64. Ethylene (ETH) and salicylic acid (SA) control the production of ROS in response to AtRbohD65. This research study revealed that most OsRboh genes contained high concentrations of these cis-acting components, comprising of light-responsive elements, MeJA-responsive elements, abscisic acid-responsive elements, and salicylic acid-responsive elements. Based on these cis-regulatory components, the OsRboh genes promoter region may responsive to several signals being controlled.The present work interaction network analysis using STRING provided insights into the potential functional associations and interacting partners of the nine OsRboh genes proteins in rice (Fig. 4). Rboh genes are important components of plant signaling networks, and they participate in various pathways that transmit signals, including their connections with different regulatory elements, including CDPK, Calcium sensor interacting protein kinase that includes calcineurin B-like, OST1, CBL/CIPK, and Ser/Thr protein kinases with a Ca2+-binding calmodulin like region66. In this study, 50 partners altogether which interacted with OsRboh genes. KEGG database revealed their connection in plant-pathogen interaction, MAPK signaling, and other mRNA Surveillance Pathways67. In plant-pathogen interaction, the OsRbohA-OsRbohI genes interacted with CDPKs (calcium-dependent protein kinases). A previous study suggested that this network model provides a comprehensive view of how Rboh proteins interact with other proteins and participate in various cellular pathways68. Similarly, other results advise that potato (Solanum tuberosum) St CDPK5 induces the phosphorylation of StRbohB and regulates the oxidative burst69. It features their importance in plant defense mechanisms, stress responses, and cellular signaling, particularly their roles in ROS production and interaction with key signaling components like CDPKs and MAPK pathways70. The Protein phosphorylation is an vital post-translational modification that has a significant impact on several regulatory signaling pathways in plants71.

Phosphorylation of specific sites on proteins can lead to changes in protein structure, resulting in changes in enzyme activity, biological action, intracellular localization, protein stability and substrate specificity.The amino acids serine (S), threonine (T), and tyrosine (Y) are important for phosphorylation72. In the present study, we predicted the 9 OsRboh proteins phosphorylation sites. The maximum number of phosphorylation sites of OsRboh genes was observed in OsRbohC by 7 predicted sites. In comparison, the minimum number was observed in OsRbohD by only 2 predicted sites (Table 2). The serine residues corresponding to S-7, S-9, S-22, S-32, S-42, S-112, and S-120 in OsRbohC were conserved in other OsRboh genes like OsRbohB-32, OsRbohE-9, OsRbohF-120, OsRbohG-22, and OsRbohH-7, 42, 112. In addition, the amino acid sequence S-5 S-238 in OsRbohD matches the phosphorylation positions of OsRbohE-5 and OsRbohI-238. Prior research has demonstrated that the Rboh gene family in two model plants, Arabidopsis along with rice, has a large number of potential interaction partners with phosphorylation sites that have been widely discovered by computational methods. This research study highlights the key role of the N-terminal amino acid residue as well as its phosphorylation in regulating various plant biological functions73. The equivalent serine residue at position 5 (S-5) was conserved in OsRbohE52. This differential conservation pattern of phosphorylation sites in the N-terminal region could contribute to the functional diversity and differential regulation of OsRboh isoforms.

MicroRNAs, a group of small non-coding RNAs, significantly control gene expression at the post-transcriptional level24. miRNA prediction revealed that OsRboh genes target diverse miRNA families (Table S2). Previous research studies have proved that the module miR5819-OsbZIP38 genes are associated with a conserved peptide upstream open reading frame (CPuORF3) in rice responses to fungal inducers74. In fsv1 ovules, there was a notable upregulation of miR5519 expression levels and a downregulation of miR1850. MiRNAs have the potential to regulate the MMC meiosis process by modulating the expression of transcription-associated genes in rice75. However mi11339 are involved in the interaction between rice plants and fungal elicitors74. In addition the functions of target Citrus miR171b SCARECROW-like (SCL) genes are positively regulated in citrus Huanglongbing HLB disease resistance76. Similarly miR171c targets GRAS plant-specific transcription factors in rice to regulate floral transition and maintain shoot apical meristem identity77. miR5799 elucidates natural light–dark cycle regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism and gene expression in rice roots78. miR531 has demonstrated its involvement in abiotic responses79. When pollen and embryo sacs develop in autotetraploid rice, miR2275 exhibits differential expression80. Recent research has demonstrated that miRNA cascades modify target pre-mRNA expression, which in turn affects how plants respond to stress81. Rice is one of the most important food crops in the world. In the latest release of miRBase (version 21), 713 mature miRNAs were found in rice, which play multiple roles in many key biological processes, such as pattern formation, leaf development, stress response, and sexual reproduction82.

The evolutionary relationship of the OsRboh genes family was analyzed across nine plant species, including rice and 8 other plant species. A total of 125 Rboh protein sequences were examined and categorized into seven groups based on variations in their protein topological structure (Fig. 5a). The absence of rice Rboh members in Groups 1 and 2 can be attributed to the evolutionary divergence between monocots such as rice and eudicots (Arabidopsis). Group 2 contains Arabidopsis Rboh members, which separated from the monocot lineage more recently than from a common ancestor shared with other plant species analyzed in this study9,11. These findings are graphically represented in (Fig. 5b), which displays the sequence counts of OsRboh genes categorized into seven groups, each depicted in a distinct color The grouping of Rboh members based on their protein topological structure suggests functional divergence and specialization within the Rboh genes family. The variations in the number of Rboh members across different plant species may reflect their specific roles in various physiological processes, such as stress responses and development60.

The OsRboh genes expression patterns across several plant tissues indicate that its expression levels vary in different tissues (roots, stems, and leaves) (Fig. 6). OsRbohA and OsRbohE have the highest expression in the roots, suggesting that their involvement in root-specific activities may be essential. These functions could include root growth, development, nutrient uptake, or responses to soil-borne stresses. Their high expression in roots aligns with previous findings that OsRbohA and OsRbohE are involved in rice tolerance to salt stress, as roots are the primary site of salt perception83. OsRbohG, OsRbohH, and OsRbohI show comparatively lower expression in stems, while OsRbohC and OsRbohD displays relatively high expression in stems compared to roots and leaves. This differential expression pattern suggests these genes may have specialized functions in stem-related processes, potentially including stem elongation, vascular development, or mechanical support84. In OsRbohC and OsRbohD the expression level was high in the leaf as compared to root and stem. The diverse expression patterns observed across different tissues highlight the functional specialization within the OsRboh genes family. This tissue-specific expression is likely a result of evolutionary adaptation, allowing rice to fine-tune ROS production and signaling in different plant parts to meet specific physiological needs or respond to localized stresses.

The OsRboh genes expression pattern in various tissues (roots, stems, and leaves) was found to be significantly different p-values (*: < 0.05, **: < 0.01, ***: < 0.0001, ns: not significant). The error bars show the standard deviation, as determined using the t-test with GraphPad Prism v.8.5.0. This experiment was conducted three times, with GAPDH as the internal reference gene.

The OsRboh genes family encodes NADPH oxidases that show crucial roles in ROS production and signaling during plant development, growth, and stress responses35. Upon (SA) treatment, the expression level of OsRbohA and OsRbohC (8 ~ sevenfold) showed a significant upregulation, suggesting their involvement in SA-mediated defense responses. Additionally, OsRbohD and OsRbohH were specifically induced by SA, indicating their potential roles in SA signaling pathways (Fig. 7). These findings promote previous studies focusing on the role NADPH oxidases play in SA-mediated defense mechanisms85. Under (MeJA) treatment the expression level of OsRbohB increasing over (~ sevenfold) times more than that of 0 h was significantly upregulated and the expression level of OsRbohG also increased in relative fold (~ fivefold) times more than of 0 h in same time 3 h (Fig. 7). This result suggests their involvement in jasmonic acid (JA) signaling and defense responses against biotic and abiotic stresses. Interestingly, OsRbohG exhibited differential expression patterns under (SA) and (MeJA) treatments, implying distinct regulatory mechanisms for SA and JA signaling pathways85. SA and JA treatment in cassava has been shown to have antagonistic effects on MeRbohC and MeRbohF gene expression, which is consistent with reports from experiments in tobacco and Arabidopsis86. The expression of the Xoo PXO99 strain was administered. In OsRbohD and OsRbohF the expression level was increased in the 12 h the relative (20 ~ 15-fold) times more than that of 0 h, both genes are upregulated and no significant change (Fig. 7). This upregulation suggests their roles in PAMP (pathogen-associated molecular pattern) triggered immunity and oxidative burst during the plant defense response against Xoo infection84,87. OsRbohA, OsRbohB, OsRbohC OsRbohD, OsRbohF, and OsRbohG appear to be involved in multiple stress responses, as they were induced by SA, MeJA, and Xoo treatments. The differential expression patterns of OsRboh genes under various stress conditions highlight their diverse functions. These findings provide a valuable understanding of OsRboh genes in stress responses to the rice crop and highlight the importance of NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS signaling in plant defense mechanisms.

qRT-PCR was used to detect the expression levels of OsRbohA-OsRbohI under the treatment of (Xoo), 0.1 mmol/L (SA), and 1.0 mmol/L (MeJA). Leaf samples were collected at 0, 3, 6, and 12 h, and two-way ANOVA was performed using GraphPad Prism v.8.5.0. The results showed that the P value was statistically significant (*: < 0.05 or **: < 0.01). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the significantly different relative expression levels under different treatment times. The experiment was repeated three times with water treatment as the control and GAPDH as the internal reference gene.

Conclusion

This research characterized 9 Rboh genes (OsRbohA to OsRbohI) from rice. Their physicochemical properties and chromosomal localization were investigated. The gene structures, motif and conserved domain distribution patterns, and cis-acting element analysis demonstrated that OsRboh genes are both divergent and conserved. Functional protein–protein interaction, phosphorylation and miRNA target sites, phylogenetic evolution, and expression patterns of OsRboh genes were investigated. OsRboh genes showed diverse expression patterns in tissues (roots, stems, and leaves). Six OsRboh genes were response to expression patterns in (MeJA), (SA), and (Xoo) treatments. OsRbohD and OsRbohF was significantly upregulation under Xoo treatments. Additionally, OsRbohA OsRbohB, OsRbohC and OsRbohG also exhibit significant upregulation (> 20-fold) under (SA) and (MeJA) environmental stress condition. These findings provide information on the regulation of OsRboh gene family expression in rice immune response disease resistance, as well as specific mechanisms and breeding applications for coordinating and increasing rice yield using Rboh genes.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript supplementary information files.

References

Zhang, Y. et al. Genome wide identification of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) genes in Citrus sinensis and functional analysis of CsRbohD in cold tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 648 (2022).

Kaur, G. & Pati, P. K. Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements of Respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) gene families in Arabidopsis and rice provides clues for their diverse functions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 62, 104–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.04.002 (2016).

Considine, M. J. & Foyer, C. H. Stress effects on the reactive oxygen species-dependent regulation of plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 5795–5806 (2021).

Rai, K. K. & Kaushik, P. Free radicals mediated redox signaling in plant stress tolerance. Life 13, 204 (2023).

Kora, D. et al. ROS-hormone interaction in regulating integrative defense signaling of plant cell. Biocell 47, 503–521 (2023).

Du, L. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) gene family in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) under abiotic and biotic stress. Genes https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14091665 (2023).

Zhao, Y. & Zou, Z. Genomics analysis of genes encoding respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) in jatropha and the comparison with castor bean. PeerJ 7, e7263. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7263 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. NADPH oxidases and the evolution of plant salinity tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 43, 2957–2968. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13907 (2020).

Chang, Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homologs (Rboh) gene family and function of GbRboh5/18 on verticillium wilt resistance in Gossypium barbadense. Front. Genet. 11, 788 (2020).

Suzuki, N. et al. Respiratory burst oxidases: the engines of ROS signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 691–699 (2011).

Zhang, H. et al. Evolutionary analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) genes in plants and characterization of ZmRBOHs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 3858 (2023).

Baxter, A., Mittler, R. & Suzuki, N. ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1229–1240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ert375 (2013).

Sagi, M. & Fluhr, R. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol. 141, 336–340. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.078089 (2006).

Sumimoto, H. Structure, regulation and evolution of Nox-family NADPH oxidases that produce reactive oxygen species. FEBS J. 275, 3249–3277 (2008).

Kobayashi, M., Kawakita, K., Maeshima, M., Doke, N. & Yoshioka, H. Subcellular localization of Strboh proteins and NADPH-dependent O2−-generating activity in potato tuber tissues. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj113 (2006).

Gui, T. Y., Gao, D. H., Ding, H. C. & Yan, X. H. Identification of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) family genes from pyropia yezoensis and their correlation with archeospore release. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 929299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.929299 (2022).

Cepauskas, D. et al. Characterization of apple NADPH oxidase genes and their expression associated with oxidative stress in shoot culture in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Culture 124, 621–633 (2016).

Cheng, C. et al. Genome-wide analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homologs in grape (Vitis vinifera L). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 24169–24186 (2013).

Yu, S. et al. Systematic study of the stress-responsive Rboh gene family in Nicotiana tabacum: Genome-wide identification, evolution and role in disease resistance. Genomics 112, 1404–1418 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the Gossypium hirsutum L. respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Ghrboh) gene family. BMC Genomics 21, 1–19 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Identification of NADPH oxidase family members associated with cold stress in strawberry. FEBS Open Bio 8, 593–605 (2018).

Zhao, Y. & Zou, Z. Genomics analysis of genes encoding respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) in jatropha and the comparison with castor bean. PeerJ 7, e7263 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Genome-wide identification, classification, evolutionary expansion and expression of Rboh family genes in pepper (Capsicum annuum L). Trop. Plant Biol. 14, 251–266 (2021).

Huang, S. et al. Genome-wide identification of cassava MeRboh genes and functional analysis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 167, 296–308 (2021).

Li, D., Wu, D., Li, S., Dai, Y. & Cao, Y. Evolutionary and functional analysis of the plant-specific NADPH oxidase gene family in Brassica rapa L. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 181727 (2019).

Sachdev, S., Ansari, S. A., Ansari, M. I., Fujita, M. & Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 10, 277 (2021).

Wang, R., He, F., Ning, Y. & Wang, G.-L. Fine-tuning of RBOH-mediated ROS signaling in plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 25, 1060–1062 (2020).

Xiao, X. et al. A novel glycerol kinase gene osNHO1 regulates resistance to bacterial blight and blast diseases in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 800625 (2022).

Solangi, F. et al. Exploring the influence of different water-treatment durations on the initial growth stage of different maize varieties.

Ji, Z., Wang, C. & Zhao, K. Rice routes of countering Xanthomonas oryzae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3008 (2018).

Shi, Y. et al. OsRbohB-mediated ROS production plays a crucial role in drought stress tolerance of rice. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 1767–1784 (2020).

Lv, Z.-Y. et al. Phytohormones jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, gibberellins, and abscisic acid are key mediators of plant secondary metabolites. World J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 7, 307. https://doi.org/10.4103/wjtcm.wjtcm_20_21 (2021).

Yoshie, Y. et al. Function of the rice gp91phox homologs OsrbohA and OsrbohE genes in ROS-dependent plant immune responses. Plant Biotechnol. 22, 127–135 (2005).

Nagano, M. et al. Plasma membrane microdomains are essential for Rac1-RbohB/H-mediated immunity in rice. Plant Cell 28, 1966–1983 (2016).

Shi, Y. et al. OsRbohB-mediated ROS production plays a crucial role in drought stress tolerance of rice. Plant Cell Rep. 39, 1767–1784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-020-02603-2 (2020).

Kawahara, Y. et al. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice 6, 1–10 (2013).

Gasteiger, E. et al. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003).

Voorrips, R. E. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93, 77–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/93.1.77 (2002).

Horton, P. et al. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm259 (2007).

Bailey, T. L. et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208 (2009).

Hu, B. et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817 (2015).

Lescot, M. et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327 (2002).

Chapman, J. M., Muhlemann, J. K., Gayomba, S. R. & Muday, G. K. RBOH-dependent ROS synthesis and ROS scavenging by plant specialized metabolites to modulate plant development and stress responses. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 32, 370–396 (2019).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638–D646. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1000 (2022).

Dai, X., Zhuang, Z. & Zhao, P. X. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W49–W54 (2018).

Guo, Z. et al. PmiREN: a comprehensive encyclopedia of plant miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D1114–D1121 (2020).

Gao, J., Thelen, J. J., Dunker, A. K. & Xu, D. Musite, a tool for global prediction of general and kinase-specific phosphorylation sites. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 2586–2600 (2010).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Ke, Y., Hui, S. & Yuan, M. Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae inoculation and growth rate on rice by leaf clipping method. Bio-protocol 7, e2568, https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.2568 (2017).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protocols 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Kimata-Ariga, Y. et al. NADP(H) allosterically regulates the interaction between ferredoxin and ferredoxin-NADP(+) reductase. FEBS Open Bio 9, 2126–2136. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.12752 (2019).

Kaur, G. & Pati, P. K. Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements of Respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) gene families in Arabidopsis and rice provides clues for their diverse functions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 62, 104–118 (2016).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D605-d612. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1074 (2021).

Ramazi, S. & Zahiri, J. Post-translational modifications in proteins: resources, tools and prediction methods. Database 2021, baab012 (2021).

Wang, J., Mei, J. & Ren, G. Plant microRNAs: biogenesis, homeostasis, and degradation. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 433008 (2019).

Conklin, P. A., Strable, J., Li, S. & Scanlon, M. J. On the mechanisms of development in monocot and eudicot leaves. New Phytol. 221, 706–724 (2019).

Kim, E.-J. et al. Genome-wide analysis of root hair preferred RBOH genes suggests that three RBOH genes are associated with auxin-mediated root hair development in rice. J. Plant Biol. 62, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-019-0006-5 (2019).

Li, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, J. & He, C. Expression and functional analysis of OsRboh gene family in rice immune response. Sheng wu Gong Cheng xue bao = Chin. J. Biotechnol. 27, 1574–1585 (2011).

Ansari, H. R. & Raghava, G. P. Identification of NAD interacting residues in proteins. BMC Bioinform. 11, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-160 (2010).

Du, L. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) gene family in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) under abiotic and biotic stress. Genes 14, 1665 (2023).

Wu, F. et al. Systematic analysis of the Rboh gene family in seven gramineous plants and its roles in response to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 603. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04571-7 (2023).

Chapman, J. M., Muhlemann, J. K., Gayomba, S. R. & Muday, G. K. RBOH-dependent ROS synthesis and ROS scavenging by plant specialized metabolites to modulate plant development and stress responses. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 32, 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00028 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. H2O2 mediates the crosstalk of brassinosteroid and abscisic acid in tomato responses to heat and oxidative stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4371–4383. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eru217 (2014).

Janicka, M., Reda, M., Mroczko, E., Wdowikowska, A. & Kabała, K. Jasmonic acid effect on Cucumis sativus L. growth is related to inhibition of plasma membrane proton pump and the uptake and assimilation of nitrates. Cells 12, 2263 (2023).

Wang, H. Q. et al. Ethylene mediates salicylic-acid-induced stomatal closure by controlling reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide production in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 294, 110464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110464 (2020).

Kaur, G., Sharma, A., Guruprasad, K. & Pati, P. K. Versatile roles of plant NADPH oxidases and emerging concepts. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.02.002 (2014).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Hu, C. H. et al. NADPH oxidases: the vital performers and center hubs during plant growth and signaling. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020437 (2020).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell 19, 1065–1080. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.048884 (2007).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638-d646. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1000 (2023).

Ardito, F., Giuliani, M., Perrone, D., Troiano, G. & Lo Muzio, L. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 40, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2017.3036 (2017).

Lee, J. M., Hammarén, H. M., Savitski, M. M. & Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 14, 201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-35795-8 (2023).

Kaur, G. & Pati, P. K. In silico insights on diverse interacting partners and phosphorylation sites of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rbohs) gene families from Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1378-2 (2018).

Baldrich, P. et al. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression in the response of rice plants to fungal elicitors. RNA Biol. 12, 847–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2015.1050577 (2015).

Yang, L. et al. Genetic subtraction profiling identifies candidate mirnas involved in rice female gametophyte abortion. G3 7, 2281–2293. https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.117.040808 (2017).

Lv, Y. et al. MicroRNA miR171b positively regulates resistance to huanglongbing of citrus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 5737 (2023).

Han, H. & Zhou, Y. Function and regulation of microRNA171 in plant stem cell homeostasis and developmental programing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23052544 (2022).

Li, H. et al. A natural light/dark cycle regulation of carbon-nitrogen metabolism and gene expression in rice shoots. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01318 (2016).

Kushawaha, A. K., Khan, A., Sopory, S. K. & Sanan-Mishra, N. Priming by high temperature stress induces microrna regulated heat shock modules indicating their involvement in thermopriming response in rice. Life https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040291 (2021).

Xia, R. et al. 24-nt reproductive phasiRNAs are broadly present in angiosperms. Nat. Commun. 10, 627. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08543-0 (2019).

Raza, A. et al. miRNAs for crop improvement. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 201, 107857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107857 (2023).

Fang, Y., Xie, K. & Xiong, L. Conserved miR164-targeted NAC genes negatively regulate drought resistance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 2119–2135 (2014).

Zhu, Y. et al. Identification of NADPH oxidase genes crucial for rice multiple disease resistance and yield traits. Rice 17, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-023-00678-5 (2024).

Li, Y., Chen, Y., Wu, J. & He, C. Expression and functional analysis of OsRboh gene family in rice immune response. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 27, 1574–1585 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. The plasma membrane NADPH oxidase OsRbohA plays a crucial role in developmental regulation and drought-stress response in rice. Physiol. Plant. 156, 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12389 (2016).

Lugassi, N. et al. Expression of Arabidopsis hexokinase in tobacco guard cells increases water-use efficiency and confers tolerance to drought and salt stress. Plants https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8120613 (2019).

Qi, J. et al. OsRbohI regulates rice growth and development via jasmonic acid signalling. Plant Cell Physiol. 64, 686–699. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcad031 (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by “Unveiling and Leading” Project of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory (B23YQ1512) and China National Seed Group (B23CQ15CP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Investigation, (S.K). Formal analysis, (S.K), (F.S). Data curation, (S.K). Writing—original draft (S.K). Supervision, (Y.C) Project administration, and Funding acquisition, (Y.C) Conceptualization (S.H), review and editing, (X.X), (Z.Z), (F.S), and (S.H).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khaskhali, S., Xiao, X., Zhang, Z. et al. Expression profile and characterization of respiratory burst oxidase homolog genes in rice under MeJA, SA and Xoo treatments. Sci Rep 15, 5936 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88731-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88731-9