Abstract

Atypical sensory responses and seeking behaviors constitute the core symptoms of autism spectrum condition (ASC). There are possible links between atypical sensory profiles and attentional challenges in ASC. Due to the paucity of studies in adults, the nature of attentional challenges and their associations with sensory profiles in autistic adults remain elusive. Here, we investigated sustained attention performance and its associations with sensory profiles in 28 autistic adult males and 23 typically developing controls (TDCs). A gradual-onset continuous performance task and the Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile were employed to assess sustained attention performance and sensory profiles, respectively. Our results revealed that the two groups exhibited comparable sustained attention performance quantified by d-prime. A statistically significant negative correlation between d-prime and sensory seeking was observed only in the ASC group. Moreover, an interaction effect of group-by-sensory seeking was observed in d-prime, suggesting a unique interplay between sensory profiles and attention in autistic individuals. In the ASC group, omission error rate and post-error slowing were statistically significantly associated with difficulties in social communication and interactions. These results contribute to understanding attentional processes in ASC and highlight the potential influence of sensory profiles on cognitive functions in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum condition (ASC) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication and interactions, accompanied by focused interests and behaviors1. Unusual sensory responses (i.e., hyper- or hypo-reactivity) to sensory inputs are prevalent and persistent in autistic individuals2,3,4. They are now recognized as core symptoms in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5). Sensory profiles are highly heterogeneous in autistic individuals5,6,7and are believed to influence various cognitive functions7,8,9,10,11, particularly attention. Thus, elucidating the intricate sensory-attention relationships is fundamental for comprehending the overall picture of this disorder.

Both selective and sustained attention are crucial in our daily adaptive behaviors and mental health12,13,14. Among autistic individuals, attentional processes often diverge from those observed in typically developing controls (TDCs). These atypical attentional patterns in autism are characterized by challenges in sustaining attention, shifting focus between stimuli, and filtering out irrelevant stimuli15,16,17. For example, studies have highlighted specific challenges in maintaining attention over extended periods in autistic individuals18,19,20,21. However, these previous studies have been primarily conducted on autistic children and adolescents. The scarcity of research, especially on sustained attention in autistic adults, emphasizes the need for a more comprehensive investigation into these atypical attentional processes and their practical implications, which are crucial for adaptation to changing environments and meeting daily life demands.

Atypical sensory responses and seeking in autism may result in a cascading effect on attentional processes and social functioning8,22,23,24. These atypical sensory profiles can impair attentional processes, leading to challenges in focusing, maintaining, and shifting attention in response to environmental demands, which can in turn influence social communication and interactions. While previous studies have investigated atypical sensory and attentional processes separately18,19,25,26, few studies have examined both from the same participants27,28. Furthermore, despite the fact that atypical sensory profiles are known to persist in adulthood4,29, prior studies have focused mainly on autistic children and adolescents. These research gaps underscore the critical need for comprehensive studies that explore the interplay between sensory processing and attention in autistic adults.

In this study, our aim was twofold: firstly, to investigate whether autistic adults demonstrate atypical sustained attention performance compared with TDCs, and secondly, to examine whether sensory profiles are associated with sustained attention performance in ASC and TDC groups, respectively. We utilized a gradual-onset continuous performance task (gradCPT)30to measure sustained attention ability for the following reasons. First, this task is well-suited for assessing inter-individual differences in sustained attention ability31,32,33. Second, the gradCPT may be more related to sensory profiles than other sustained attention tasks (e.g., AX-CPT), as it involves continuously and subtly changing stimuli. These dynamic stimuli may induce boredom, especially in individuals with high sensory-seeking tendencies. We first assessed whether, compared with the TDC group, the ASC group exhibited atypical sustained attention ability, as quantified by d-prime. We then investigated the associations between d-prime and sensory profiles measured by the Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (AASP)34 separately for the ASC and TDC groups. These analyses could advance our understanding of ASC and provide insight into therapeutic intervention approaches to this disorder.

Results

Gradual-onset continuous performance task

Twenty-eight adult males with autism and 23 typically developing adult controls participated in this study. Participants completed questionnaires, including AASP, Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ), and Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), and underwent a gradCPT to measure their sustained attention ability. The details of gradCPT are described elsewhere30,32. Briefly, the gradCPT used 10 grayscale, circular photographs of mountain scenes and 10 of city scenes, respectively. The images were presented in random order at a ratio of 10% mountain to 90% city, ensuring that no identical image appeared in consecutive trials. Each transition between images was achieved through linear pixel-by-pixel interpolation, lasting 800 ms. All images were shown on an LCD monitor with a 60-Hz refresh rate. Participants were seated in a chair with their heads stabilized by a chinrest, positioned 57 cm from the display. Participants were instructed to press a button for each city scene and to refrain from responding to mountain scenes. Participants were first familiarized with gradCPT by the 30-second practice of gradCPT, followed by an 8-minute run of the gradCPT. According to previous studies31,32, we calculated several behavioral metrics, including d-prime, Coefficient of Variation (CoV), Post-Error Slowing (PES), omission error, and commission error. In this study, we considered each participant’s d-prime, reflecting the ability to discriminate between city and mountain scenes, as a primary outcome, while other behavioral metrics were considered as the secondary outcomes. The derivations and explanations of primary and secondary outcomes are described in the Materials and Methods section.

Demographic data

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data of participants in the ASC and TDC groups. Two-tailed, two-sample t-tests showed no significant differences in age and full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) between the two groups (P > 0.09). The main effect of the group was observed in the total scores of the AQ and the total and subscale scores of the SRS (P < 0.001). For the sensory profile, a significant group effect was observed in all subscales of AASP (P < 0.05), except for sensory avoidance (P = 0.12). For low registration and sensory sensitivity, the ASC group exhibited higher scores than the TDC group, while they exhibited lower scores in sensory seeking (see Table 1).

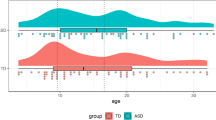

Group comparisons on behavioral metrics

Figure 1 presents the results of the behavioral data. Statistical analyses revealed no significant between-group difference in d-prime (t-value = −1.30, Cohen’s d = −0.35, P = 0.20). For the secondary outcomes, we also found no significant between-group differences (CoV: t-value = 1.11, Cohen’s d = 0.30 P = 0.27; PES: t-value = −1.71, Cohen’s d = −0.49, P = 0.09; Omission error: t-value = 0.43, Cohen’s d = 0.12, P = 0.67; and Commission error: t-value = 0.14, Cohen’s d = 0.04, P = 0.89). These results remained consistent after adjusting for age and IQ as nuisance covariates.

As complementary analyses, we conducted the Fligner-Killeen tests to check the homogeneity of group variance. No significant between-group differences were found (all P > 0.24), except for CoV (χ2 = 3.96, df = 1, Cliff’s δ = 0.25, P = 0.047).

Relationships between sensory profiles and behavioral metrics

Figure 2 shows the results of correlational analyses between the sensory profiles and the primary outcome (d-prime). In the ASC group, sensory seeking exhibited a significant negative correlation with d-prime (r = −0.49, q = 0.03), while other sensory profiles did not (all P > 0.20). In the TDC group, no sensory profile showed significant correlations with d-prime (all P > 0.17). We conducted a linear hypothesis test to confirm whether sensory seeking was differentially associated with d-prime between the two groups (i.e., the interaction effect of group and sensory seeking). The linear hypothesis test confirmed a significant difference (F(1,47) = 5.09, Cohen’s f2 = 0.11, P = 0.028). These results were unchanged after including age and IQ as nuisance covariates. For the secondary outcomes, we did not find statistically significant correlations in both groups (all P > 0.05).

Relationships between sensory symptoms and d-prime performance in the ASC and TDC groups. (A) Low registration, (B) Sensory seeking, (C) Sensory sensitivity, and (D) Sensory avoidance. Each subplot represents the linear relationship between sensory profile scores (x-axis) and d-prime (y-axis) with the line of best fit and its confidence interval shaded in grey. Data points are color-coded: red for the autism spectrum condition (ASC) group and blue for the typically developing control (TDC) group.

Relationships between the clinical symptoms and behavioral metrics in the ASC group

Pearson correlation analyses found no significant correlation between d-prime and clinical symptoms (all P > 0.13). We found no significant correlations with the AQ and SRS scores (all P > 0.17) for the secondary outcomes. PES exhibited a negative correlation with the ADOS communication score (r = −0.44, P = 0.02), while the omission error positively correlated with the ADOS reciprocal social interaction score (r = 0.39, P = 0.04).

Discussion

This study investigated whether autistic adults exhibited atypical sustained attention performance compared with TDCs and whether sensory profiles were associated with sustained attention performance measured by the gradCPT separately for the two groups. Our findings indicate comparable sustained attetion performance between the two groups. In the ASC group, sensory seeking was negatively correlated with sustained attention, a pattern absent in the TDC group. This differential relationship, confirmed through linear hypothesis testing, underscores the unique interplay between sensory processing and attentional functioning in ASC. These findings provide new insight into the complicated sensory-attention relationships in ASC and offer new suggestions for understanding and addressing attention-related challenges in this disorder.

Contrary to prior research suggesting sustained attentional challenges in ASC18,19,20,21, our study observed that sustained attention ability in the ASC group was comparable with those in the TDC group. There are three possible explanations for this discrepancy. One possible explanation is the variation in methodological approaches. For example, conventional tasks for measuring sustained attention, such as the Sustained Attention to Response Task, employ a sequence of discrete stimuli, thereby making it challenging to remove the external cues triggered by the abrupt beginnings and endings of these stimuli35. In contrast, the gradCPT presents stimuli that evolve subtly over time, eliminating such external cues. This less influence of external, stimulus-driven attention could explain the discrepancies with earlier research. The second possible explanation pertains to the characteristics of the task used in this study. Sustained attention performance is influenced by task demands and task monotony, with higher cognitive load accelerating the depletion of attentional resources and higher monotony fostering attentional drift and mind wandering36. The gradCPT, characterized by relatively low cognitive demands and a brief duration of 8 min, may not have imposed sufficient strain to reveal group differences in sustained attention abilities. Another possible explanation is differences in developmental stages. Previous research has predominantly documented attentional challenges in autistic children and adolescents18,19, while studies focusing on adults have encompassed a broader age spectrum, ranging from 19 to 50 years, and even including older adults20,21. This disparity in the ages of participants among various studies may lead to inconsistencies in results. There is evidence suggesting that certain cognitive functions, including attention, may develop toward typical levels as autistic individuals age37. Such complex relationships between cognitive functions and developmental stages obscure the understanding of challenges in the cognitive functions of ASC. Future longitudinal studies are necessary to understand the developmental trajectories of attentional profiles in ASC across the lifespan.

Our study observed that sensory seeking was negatively associated with sustained attention performance in the ASC group but not in the TDC group, suggesting a possibility that high levels of sensory seeking may reflect weak top-down attention in ASC. Sensory seeking refers to high neurological thresholds with a tendency to actively seek stimuli34. Since the gradCPT is characterized by continuously changing stimuli of weak stimulus intensity and fewer external cues than other sustained attention tasks, subjects must maintain their attention in a top-down manner during the task. Thus, prolonged periods of continuous weak stimulus intensity may cause boredom and difficulty maintaining top-down attention in autistic individuals who exhibit a high propensity for sensory seeking.

The atypical interaction between sensory seeking and attention observed in this study is consistent with previous findings11. A potential explanation is that sensory factors, such as sensory sensitivity, may exacerbate the negative impact of sensory seeking on cognitive function. For instance, a previous animal study demonstrated that mice exposed to excessive sensory stimulation during development exhibited increased sensory seeking and impaired cognition38. Moreover, several previous studies have reported heightened sensory sensitivity in autistic individuals compared to controls29,39. In our additional analyses, we included sensory sensitivity as a covariate in a general linear model with diagnosis, sensory seeking, and their interaction to investigate its potential role in modulating the relationship between sensory seeking and cognitive function (i.e., d-prime). The results indicated that while sensory sensitivity was not significantly associated with d-prime (t-value = −1.31, P = 0.20), the interaction between diagnosis and sensory seeking remained statistically significant (t-value = −2.16, P = 0.036). These findings suggest that the relationship between sensory seeking and cognitive function differs between autistic and typically developing individuals, independent of sensory sensitivity. Atypical sensory sensitivity during development may contribute to increased sensory seeking, but its role in influencing sustained attention is likely limited based on our current data.

The sensory-attention relationship observed in this study may be related to the degree of functional alterations in the cognitive control network in the autistic brain. The cognitive control network comprises several brain regions, such as the inferior frontal cortex (IFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). This network is associated with top-down attention40and has been shown to play a crucial role in situations with perceptual uncertainty41or when detecting environmental changes42. Furthermore, this region has been associated with sensory seeking behaviors43,44. A recent meta-analysis has reported that, compared with the TDC group, the ASC group exhibits altered brain activity in this network (e.g., IFC and ACC) during cognitive control45. Our observations, combined with prior neuroimaging findings, may imply that high levels of sensory seeking reflect weak top-down attention through functional alterations of the cognitive control network in the autistic brain. Further studies combining neuroimaging techniques will shed light on the triadic relationship between sensory seeking, brain function, and sustained attention in autistic individuals.

Prior studies have investigated alterations of omission errors or diminished PES in autistic children46,47,48,49and adults50,51, but no studies have reported significant associations with the clinical symptoms. Our exploratory analyses found that omission error and PES were significantly correlated with specific ADOS subscales, respectively. PES was negatively correlated with the ADOS communication score, suggesting that greater communication difficulties may impact post-error adjustments; in contrast, omission error was positively correlated with the ADOS reciprocal social interaction score, indicating that social interaction challenges may contribute to attentional lapses or omissions. These differential associations highlight the need for further research to explore the specific mechanisms linking error monitoring processes to distinct clinical features in ASC.

The current results should be interpreted with caution. First, we focused solely on sustained attention because of its implications for academic and social difficulties in ASC12,52. Thus, it is unclear whether all attentional processes are comparable between the ASC and TDC groups. Second, this study did not include female participants to increase the biological homogeneity of the sample. Prior research has demonstrated sex differences in attention regardless of diagnosis53; this choice limits the applicability of our findings to the broader ASC population. Third, we did not consider the existence of sensory subtypes within the ASC group. Prior studies have demonstrated the presence of sensory subtypes in autistic individuals5,6,10. These sensory subtypes may exhibit distinct patterns of challenges in cognitive functions, which may have influenced our findings. Furthermore, we did not investigate the extent to which individual items in sensory seeking contributed to our findings. Therefore, future studies with a larger sample size are necessary to investigate the associations between sensory seeking and cognitive functions in an item-wise manner while considering these sensory subtypes. Fourth, unlike previous studies utilizing the AASP29,39,54,55, the group differences in sensory avoidance did not reach statistical significance. This is primarily due to the tendency of the TDCs in this study to exhibit high sensory avoidance. However, the recruitment methods employed in this study were consistent with those used in our previous studies29,54, and there are prior studies in which TDCs demonstrated similar sensory avoidance values56,57. In addition, we observed that the ASC group exhibited higher sustained attention ability (t-value = −2.09, Cohen’s d = −0.59, P= 0.04) after excluding poor performers (i.e., those more than two standard deviations below the mean), suggesting outliers may influence group comparisons. Thus, the possibility of sampling bias resulting from the modest sample size must be considered. Indeed, a post-hoc power analysis indicates that the sample size in this study is insufficient for detecting small and medium effects. Therefore, future research with a larger sample size is warranted. Fifth, since we recruited TDC and ASC participants using different methods, our findings may be potentially biased due to differences in recruitment procedures. Future research is necessary to recruit participants using the same methods to determine whether our results can be replicated. Sixth, a self-report scale was used to evaluate each individual’s sensory profile. Although the AASP has been employed in numerous studies29,39,54,55, self-report measures are sensitive to individuals’ awareness of their issues and differences from most others. Future research may benefit from incorporating objective measures to complement this approach. Sixth, the current study was cross-sectional and focused on autistic adults. Thus, the causality of the sensory-attention relationships and the developmental perspective are lacking. Given the evidence that autistic individuals exhibit atypical brain development compared with TDCs58, the sensory-attention relationship in ASC may also differ among developmental stages. Seventh, this study employed the JART to estimate IQ scores in the TDC group instead of the WAIS. While the JART has been validated in healthy controls59and is widely used in Japanese clinical studies54,60,61,62, it is based on reading ability, which introduces the potential for under- or overestimation of certain aspects of intelligence. Future studies could benefit from examining sustained attention while controlling for IQ scores estimated using the WAIS to provide a more comprehensive assessment. Lastly, this study did not assess the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in autistic participants. Given that 50–70% of autistic individuals also present with comorbid ADHD63and individuals with ADHD show atypical sensory profiles29,57,64, we cannot rule out the possibility that our findings may be attributable to the ADHD symptoms. Future studies should explore these aspects comprehensively, including multiple behavioral tasks, a broader gender spectrum, a larger sample size from a general population, multiple developmental stages, and individuals with ADHD.

In conclusion, the current study finds comparable sustained attention ability and its unique relationship with sensory seeking in autistic adults. The current findings highlight the importance of sensory symptoms on cognitive functions in autistic adults, and further research investigating the relationship between sensory profiles and cognition in ASC is warranted.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All participants provided written informed consent. The institutional review board at Showa University Karasuyama Hospital approved recruitment procedures and experimental protocols, which were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Twenty-eight autistic adult males (30.9 ± 5.3 years old) participated in this study. Autistic participants were recruited from the outpatient unit of Karasuyama Hospital, Showa University, Tokyo, Japan. A clinical team assessed the developmental history, present illness, life history, and family history and then made clinical diagnoses based on the DSM-IV-TR, in line with our previous studies29,54. The ADOS Module 465,66 was administered to all the autistic participants except for one participant. Twenty-four of the 27 autistic participants met the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) on the ADOS, comprising 16 diagnosed with autism and 8 with ASD. In contrast, three autistic participants did not meet the diagnostic criteria for ASD. Among these, two participants failed to reach the cutoff score on the “Communication” subscale of the ADOS (< 2) but satisfied the cutoff scores for both the “Reciprocal Social Interaction” subscale and the total ADOS score. One participant did not meet the cutoff scores for the “Reciprocal Social Interaction” subscale (< 4) and the total score (< 7) but did meet the cutoff for the “Communication” subscale. Consequently, these three participants were included in the ASC group. Twenty-three typically developing adult controls (TDC; 28.2 ± 6.2 years old) participated in this study. TDCs were recruited via an advertisement that included information such as a brief summary of the research objectives, inclusion criteria (e.g., age ≧ 20 years old), and exclusion criteria (e.g., a history of psychiatric or neurological problems). In this study, we asked controls to indicate if they had a history of psychiatric or neurological problems, severe medical conditions, or a family member with a history of psychiatric problems. None of the TDCs met these criteria.

The IQ scores of autistic participants were evaluated using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV), WAIS-III, or WAIS-Revised. Based on previous studies54, the IQ scores of control participants were estimated using a Japanese version of the National Adult Reading Test (JART)59. Based on the National Adult Reading Test (NART) for English-speaking populations67, the JART was developed and validated to estimate the IQ scores of normal Japanese individuals by scoring their reading ability of 25 words printed in Kanji (adopted logographic Chinese characters)59. Furthermore, it has been widely used in Japanese clinical studies to estimate IQ scores in controls60,61. All the participants completed the AASP, which assesses sensory profiles in four domains: low registration, sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoidance34. The four domains of the AASP differ in terms of the ways in which neurological thresholds (i.e., high or low) interact with behavioral responses (i.e., passive or active). Low registration refers to high neurological thresholds and passive behavioral responses, while sensory seeking refers to high neurological thresholds and active behavioral responses. Both sensory sensitivity and sensory avoidance refer to low neurological thresholds, while the former and latter denote passive and active behavioral responses, respectively. Here, a person with ‘high neurological thresholds’ would take longer to perceive stimuli or be more likely to miss stimuli compared with a person with low neurological thresholds. All the participants completed the AQ68and SRS, Second Edition69 to characterize the autistic traits.

Behavioral analyses for gradual-onset continuous performance task

We calculated behavioral metrics from the gradCPT data of each participant, including d-prime, CoV, PES, omission error, and commission error, according to previous studies30,31. The d-prime is an index of perceptual sensitivity or accuracy that incorporates both hit and false alarm rates. The d-prime is calculated using the following formula:

d-prime = Z(hit rate) - Z(false alarm rate),

where Z() represents the inverse cumulative distribution function, which converts hit and false alarm rates into z-scores. In this study, a hit is defined as correctly omitting a response to a mountain scene image, while a false alarm refers to an omission error where participants fail to respond to a city scene image. A commission error occurs when participants fail to inhibit a response to a mountain scene image. CoV is a measure used to evaluate trial-to-trial fluctuations in attention. It is calculated based on correct responses to city scene trials and is defined as the standard deviation of reaction times (RTs) divided by the mean RT for each participant. Higher CoV values indicate greater difficulties in maintaining attention. On the other hand, PES measures the extent to which participants delay their responses following an incorrect response, providing an indicator of error monitoring processes.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2. To evaluate the impact of the group on the primary outcome, we used Welch’s two-sample t-test. The statistical threshold was set to P < 0.05.

We performed Pearson correlation analyses to examine whether sensory profiles were associated with sustained attention. Since three out of the four subscales of AASP exhibited significant between-group differences (see Table 1), we performed these analyses in each group. The statistical threshold was set to P< 0.05, and we applied a false discovery rate (FDR) correction method70. Once statistically significant correlations between sustained attention and sensory profiles were identified in any group, we examined the interaction effect of group and sensory profile on the primary outcome using a linear hypothesis test, which evaluates the statistical contribution of a specific coefficient within a general linear model.

As exploratory analyses, we also performed Pearson correlational analyses to investigate the associations of behavioral metrics with the clinical symptoms (i.e., AQ, SRS, and ADOS scores) in the ASC group. Due to the exploratory nature of these analyses, we set the statistical threshold to P < 0.05. The same procedures were applied to the secondary outcomes. We also reported the effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d) across all the statistical analyses.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) (American Psychiatric Pub, 2013).

Ausderau, K. et al. National survey of sensory features in children with ASD: factor structure of the sensory experience questionnaire (3.0). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 915–925 (2014).

Baranek, G. T., David, F. J., Poe, M. D., Stone, W. L. & Watson, L. R. Sensory experiences Questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 47, 591–601 (2006).

Leekam, S. R., Nieto, C., Libby, S. J., Wing, L. & Gould, J. Describing the sensory abnormalities of children and adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 894–910 (2007).

Scheerer, N. E. et al. Exploring sensory phenotypes in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism. 12, 67 (2021).

Kaneko, A. et al. Sensory and social subtypes of Japanese individuals with Autism Spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 3133–3143 (2023).

Ben-Sasson, A., Gal, E., Fluss, R., Katz-Zetler, N. & Cermak, S. A. Update of a Meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: a New Decade of Research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 4974–4996 (2019).

Baranek, G. T. et al. Cascading effects of attention disengagement and sensory seeking on social symptoms in a community sample of infants at-risk for a future diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 30–40 (2018).

Watson, L. R. et al. Differential associations between sensory response patterns and language, social, and communication measures in children with autism or other developmental disabilities. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, 1562–1576 (2011).

Lane, A. E., Young, R. L., Baker, A. E. Z. & Angley, M. T. Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 40, 112–122 (2010).

Neufeld, J. et al. The impact of atypical sensory processing on adaptive functioning within and beyond autism: the role of familial factors. Autism 25, 2341–2355 (2021).

Gallen, C. L. et al. Contribution of sustained attention abilities to real-world academic skills in children. Sci. Rep. 13, 2673 (2023).

Isbell, E., Calkins, S. D., Swingler, M. M. & Leerkes, E. M. Attentional fluctuations in preschoolers: direct and indirect relations with task accuracy, academic readiness, and school performance. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 167, 388–403 (2018).

Keller, A. S., Leikauf, J. E., Holt-Gosselin, B., Staveland, B. R. & Williams, L. M. Paying attention to attention in depression. Transl Psychiatry. 9, 279 (2019).

Landry, R. & Bryson, S. E. Impaired disengagement of attention in young children with autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 45, 1115–1122 (2004).

Chawarska, K., Volkmar, F. & Klin, A. Limited attentional bias for faces in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 67, 178–185 (2010).

Vivanti, G., Fanning, P. A. J., Hocking, D. R., Sievers, S. & Dissanayake, C. Social attention, joint attention and sustained attention in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Williams Syndrome: convergences and divergences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 1866–1877 (2017).

Chien, Y. L. et al. Visual memory and sustained attention impairment in youths with autism spectrum disorders. Psychol. Med. 45, 2263–2273 (2015).

Chien, Y. L. et al. Impaired sustained attention, focused attention, and vigilance in youths with autistic disorder and Asperger’s disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 8, 881–889 (2014).

Wichers, R. H. et al. Modulation of brain activation during executive functioning in autism with citalopram. Transl Psychiatry. 9, 286 (2019).

Geurts, H. M. & Vissers, M. E. Elderly with autism: executive functions and memory. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 665–675 (2012).

Dellapiazza, F. et al. Links between sensory processing, adaptive behaviours, and attention in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 270, 78–88 (2018).

Liss, M., Saulnier, C., Fein, D. & Kinsbourne, M. Sensory and attention abnormalities in autistic spectrum disorders. Autism 10, 155–172 (2006).

Damiano-Goodwin, C. R. et al. Developmental sequelae and neurophysiologic substrates of sensory seeking in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 41–53 (2018).

Green, S. A. et al. Neurobiology of sensory overresponsivity in Youth with Autism Spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 72, 778–786 (2015).

Remington, A., Swettenham, J., Campbell, R. & Coleman, M. Selective attention and perceptual load in autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Sci. 20, 1388–1393 (2009).

Crasta, J. E., Salzinger, E., Lin, M. H., Gavin, W. J. & Davies, P. L. Sensory Processing and attention profiles among children with sensory Processing disorders and Autism Spectrum disorders. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 14, 22 (2020).

Pastor-Cerezuela, G., Fernández-Andrés, M. I. & Sanz-Cervera, P. Marín-Suelves, D. The impact of sensory processing on executive and cognitive functions in children with autism spectrum disorder in the school context. Res. Dev. Disabil. 96, 103540 (2020).

Ohta, H. et al. White matter alterations in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in relation to sensory profile. Mol. Autism. 11, 77 (2020).

Esterman, M., Noonan, S. K., Rosenberg, M. & Degutis, J. In the zone or zoning out? Tracking behavioral and neural fluctuations during sustained attention. Cereb. Cortex. 23, 2712–2723 (2013).

Fortenbaugh, F. C., Rothlein, D., McGlinchey, R., DeGutis, J. & Esterman, M. Tracking behavioral and neural fluctuations during sustained attention: a robust replication and extension. Neuroimage 171, 148–164 (2018).

Fortenbaugh, F. C. et al. Sustained attention across the Life Span in a sample of 10,000: dissociating ability and strategy. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1497–1510 (2015).

Rosenberg, M. D. et al. A neuromarker of sustained attention from whole-brain functional connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 165–171 (2016).

Brown, C. & Dunn, W. Adolescent/adult sensory profile. (2002).

Huang, H., Li, R. & Zhang, J. A review of visual sustained attention: neural mechanisms and computational models. PeerJ 11, e15351 (2023).

Thomson, D. R., Besner, D. & Smilek, D. A resource-control account of sustained attention: evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 82–96 (2015).

Weiss, E. M. et al. Age-moderating effect in prepotent response inhibition in boys with Asperger syndrome: a 2.5 years longitudinal study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 269, 361–364 (2019).

Ravinder, S. et al. Excessive Sensory Stimulation during Development Alters Neural Plasticity and Vulnerability to Cocaine in Mice. eNeuro 3, (2016).

Habata, K. et al. Relationship between sensory characteristics and cortical thickness/volume in autism spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 11, 616 (2021).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002).

Tsumura, K. et al. Perceptual uncertainty alternates top-down and bottom-up fronto-temporal Network Signaling during response inhibition. J. Neurosci. 42, 4567–4579 (2022).

Downar, J., Crawley, A. P., Mikulis, D. J. & Davis, K. D. A multimodal cortical network for the detection of changes in the sensory environment. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 277–283 (2000).

Coffman, B. A. et al. Trait sensation seeking is associated with heightened beta-band oscillatory dynamics over left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex during reward expectancy. J. Affect. Disord. 292, 67–74 (2021).

Holmes, A. J., Hollinshead, M. O., Roffman, J. L., Smoller, J. W. & Buckner, R. L. Individual Differences in Cognitive Control Circuit Anatomy Link Sensation Seeking, Impulsivity, and Substance Use. J. Neurosci. 36, 4038–4049 (2016).

Lukito, S. et al. Comparative meta-analyses of brain structural and functional abnormalities during cognitive control in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Med. 50, 894–919 (2020).

Xiao, T. et al. Response inhibition impairment in high functioning autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence from near-infrared spectroscopy data. PLoS One. 7, e46569 (2012).

Hwang-Gu, S. L. et al. Symptoms of ADHD affect Intrasubject Variability in youths with Autism Spectrum Disorder: an ex-gaussian analysis. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 48, 455–468 (2019).

Vlamings, P. H. J. M., Jonkman, L. M., Hoeksma, M. R., van Engeland, H. & Kemner, C. Reduced error monitoring in children with autism spectrum disorder: an ERP study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 28, 399–406 (2008).

Sokhadze, E. et al. Impaired error monitoring and correction function in Autism. J. Neurother. 14, 79–95 (2010).

Möde, L. et al. Cognitive control in adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: a study with event-related potentials. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1180827 (2023).

Bogte, H., Flamma, B., van der Meere, J. & van Engeland, H. Post-error adaptation in adults with high functioning autism. Neuropsychologia 45, 1707–1714 (2007).

Andrade, B. F., Brodeur, D. A., Waschbusch, D. A., Stewart, S. H. & McGee, R. Selective and sustained attention as predictors of social problems in children with typical and disordered attention abilities. J. Atten. Disord. 12, 341–352 (2009).

May, T., Cornish, K. & Rinehart, N. J. Gender profiles of behavioral attention in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Atten. Disord. 20, 627–635 (2016).

Itahashi, T. et al. Neural correlates of shared sensory symptoms in autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Commun. 2, fcaa186 (2020).

Kuno-Fujita, A. et al. Sensory Processing patterns and Fusiform Activity during Face Processing in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 13, 741–750 (2020).

Escelsior, A. et al. Sensation seeking correlates with increased white matter integrity of structures associated with visuospatial processing in healthy adults. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1267700 (2023).

Kamath, M. S. et al. Sensory profiles in adults with and without ADHD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 104, 103696 (2020).

Uddin, L. Q., Supekar, K. & Menon, V. Reconceptualizing functional brain connectivity in autism from a developmental perspective. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 458 (2013).

Matsuoka, K., Uno, M., Kasai, K., Koyama, K. & Kim, Y. Estimation of premorbid IQ in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease using Japanese ideographic script (Kanji) compound words: Japanese version of National Adult Reading Test. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 60, 332–339 (2006).

Oya, M. et al. Increased glutamate and glutamine levels and their relationship to astrocytes and dopaminergic transmissions in the brains of adults with autism. Sci. Rep. 13, 11655 (2023).

Okazaki, K. et al. Discrimination in the clinical diagnosis between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls using eye movement and cognitive functions. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 77, 393–400 (2023).

Shibukawa, S. et al. Alterations in subcortical magnetic susceptibility and disease-specific relationship with brain volume in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 14, 164 (2024).

Rong, Y., Yang, C. J., Jin, Y. & Wang, Y. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 83, 101759 (2021).

Bijlenga, D., Tjon-Ka-Jie, J. Y. M., Schuijers, F. & Kooij, J. J. S. Atypical sensory profiles as core features of adult ADHD, irrespective of autistic symptoms. Eur. Psychiatry. 43, 51–57 (2017).

Gotham, K., Risi, S., Pickles, A. & Lord, C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 613–627 (2007).

Gotham, K., Pickles, A. & Lord, C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 693–705 (2009).

Nelson, H. E. & National Adult Reading Test (NART). For the Assessment of Premorbid Intelligence in Patients with Dementia: Test Manual (NFER Nelson, 1982).

Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S. & Tojo, Y. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) in Japan: a cross-cultural comparison. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 36, 263–270 (2006).

Constantino, J. N. Social Responsiveness Scale Second Edition (SRS-2): Manual (Western Psychological Services (WPS), 2012).

Storey, J. D. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 64, 479–498 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP18dm0307008. The study was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 19K03370, 23K06996, 23K11798, and 24K10715. We would like to thank Noriko Ishimura, Mika Kato, and Taku Sato for their efforts in the recruitment of participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I. and R.H. designed this study. T.I., R.A., H.O., and M.N. recruited participants, and T.I. collected behavioral and clinical data. T.I. analyzed the data. T.I. wrote the original draft of this manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Itahashi, T., Aoki, R., Nakamura, M. et al. Sensory seeking and its influence on sustained attention performance in adult males with Autism Spectrum Condition. Sci Rep 15, 4047 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88733-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88733-7