Abstract

We aimed to examine the effects of sodium and potassium intake on the risk of diabetes mellitus (DM). In a cohort of 99,552 working-age Korean adults (60,591 men; mean age 39.7 ± 6.9 and 38,961 women; mean age 38.4 ± 6.5), we longitudinally evaluated the risk of DM in relation to quartile levels of sodium intake, potassium intake, and the sodium-potassium ratio. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the risk of DM by calculating adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident DM (adjusted HR [95% CI]). In men, sodium intake was not associated with the risk of DM (first quartile: reference, second quartile: 0.96 [0.87–1.07], third quartile: 0.94 [0.84–1.05], and fourth quartile: 1.02 [0.89–1.18]). Women did not show a significant association between sodium intake and the risk of DM (first quartile: reference, second quartile: 0.87 [0.69–1.09], third quartile: 1.02 [0.81–1.29], and fourth quartile: 1.01 [0.76–1.33]). Additionally, potassium intake and the sodium-potassium ratio were not significantly associated with the risk of DM in either men or women. In conclusion, no significant association was observed between sodium or potassium intake and the risk of DM among working-age Korean adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A healthy dietary pattern is a key factor for preventing chronic diseases and promoting overall health. It is essential to reduce the risk of obesity-associated conditions, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases1,2. Conversely, an unhealthy dietary pattern is widely recognized as a major contributor to the development of chronic diseases.

DM is one of the most common chronic diseases, with an explosive increase in global prevalence3. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reports that the worldwide prevalence of DM has reached 10.5%, with almost half (44.7%) of adults being undiagnosed4. The IDF has also indicated that 537 million adults have been diagnosed with DM, which is an increase of 16% (approximately 7 million) since the estimates made in 20194. Fortunately, studies have demonstrated that dietary interventions with healthy foods are effective in the prevention and remission of DM by controlling body weight5,6,7.

High sodium and low potassium intakes are considered characteristics of unhealthy dietary patterns. Excessive salt and low potassium intakes are closely linked to an increased risk of hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic kidney disease, which are associated with morbidity and mortality among patients with DM8,9,10. Therefore, patients with DM are required to strictly limit their sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg/day to minimize the harmful effects of sodium11. This recommendation is based on observational evidence suggesting that high sodium intake is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in patients with DM12,13.

Previous studies have investigated the association between sodium intake and DM based on the adverse effects of high sodium intake in patients with DM. A meta-analysis indicated that individuals with DM have higher sodium intake and urinary sodium excretion than those without DM14. However, sodium intake was not found to be associated with DM in the meta-analysis14. Although a recent study showed an increased risk of type 2 DM proportional to the frequency of adding salt to foods, this study did not assess the association between the amount of salt intake and the risk of DM15. Moreover, few studies have longitudinally analyzed the risk of DM in relation to sodium intake. Thus, despite reports from previous studies, the evidence is still far from confirming the causative relationship between sodium intake and the development of DM.

To ascertain the effects of sodium and potassium intake on the development of DM, we longitudinally evaluated the risk of incident DM according to quartile levels of sodium intake among 99,552 Koreans without diabetes. Additionally, we quantified the risk of incident DM in relation to potassium intake and the sodium-to-potassium intake ratio (sodium-potassium ratio).

Methods

Study design and participants

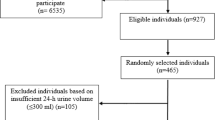

This retrospective cohort study was based on the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study (KSHS). The KSHS is a cohort study that investigated the medical data of Koreans who had received periodic health checkups at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital. Among the KSHS participants, we initially enrolled 189,008 who responded to a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) between March 2011 and December 2012. For participants who underwent several health checkups during the study period, the data from the first health checkup were regarded as baseline data. Among the 189,008 participants, we excluded 70,679 who met the following exclusion criteria: 11,761 participants whose total calorie intake was < 800 or ≥ 4,000 kcal/day in men and < 500 or ≥ 3,500 kcal/day in women; 9,475 with underlying DM; 45,617 with one or more missing covariate values; and 3,826 with a history of serious diseases (cancer, stroke, or coronary artery disease) affecting dietary patterns. Of the 118,329 participants, 99,552 followed up between January 2013 and December 2018, and thus, they were selected as eligible study participants.

Demographic and clinical measurements

The study data included a medical history assessed using a self-administered questionnaire and anthropometric and laboratory measurements. All study participants were asked to respond to a health-related behavioral questionnaire that included topics on alcohol consumption (type of alcoholic beverage and frequency of consumption), smoking (never, former, current), education level (higher or less than a college degree), and exercise (frequency, duration, and intensity). Physical activity was assessed using the Korean-validated version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form16. Hypertension was defined as a prior diagnosis of hypertension, current use of antihypertensive medication, or having measured blood pressure ≥ 140/90. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (kilograms) by the square of the height (meters2). Participants with fasting glucose > 100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 5.7% were diagnosed with prediabetes17. DM was defined as any of the following conditions: fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, current use of glucose-lowering medication, and a prior diagnosis of DM18. Blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein after more than 12 h of fasting. The hexokinase method was used to measure fasting serum glucose, and HbA1c was measured using an immunoturbidimetric assay with a Cobra Integra 800 automatic analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Dietary assessment

In the KSHS, nutrient intake was assessed using the Korean version of the FFQ. A detailed description and validation of the FFQ have been described in previous studies19,20. The FFQ includes 106 food items commonly consumed by Korean adults. The frequency of food consumption is composed of nine categories (never or rarely, once a month, two or three times a month, once or twice a week, three or four times a week, five or six times a week, once a day, twice a day, and three times a day) and three serving sizes for each food item. Food photographs with typical intake portions were also included to enhance the participants’ understanding and study reliability. The consumption frequency of each food item selected by the study participants was converted into the daily frequency of consumption. Daily sodium intake was calculated by multiplying the amount of sodium contained in the selected serving size of foods by the daily frequency of those foods. Total energy and nutrient intakes, including sodium intake, were calculated using Can-Pro 3.0 software developed by The Korean Nutrition Society. Detailed explanations of the KSHS and FFQ data are provided in our previous studies21,22.

Statistical analysis

Within the four groups classified by quartile levels of sodium intake, data are presented as means ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables at baseline. Demographic, clinical, and dietary parameters among the four groups were compared using analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for DM and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) in each study group (adjusted HR [95% CI]). Covariates of the multivariable model were selected from the factors affecting dietary patterns and the development of DM. Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) were used to determine causal relationships and suitability of the selected covariates. DAGs were computed using DAGitty (v3.1, www.dagitty.net), and it was confirmed that the adjusted covariates were correctly selected (Supplementary Fig. S1). The multiple covariates included age, regular exercise, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake (g/day), hypertension, education, total calorie intake, and dietary fiber intake. To verify multicollinearity among the variables, we analyzed the variance inflation factor (VIF) and confirmed there were no variables with a VIF greater than 10. To minimize the distortion of results by outliers of sodium or potassium intake, we conducted an additional analysis excluding participants whose sodium or potassium intake had a Z score > 3 or <−3.

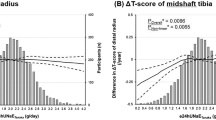

To justify the proportional hazards assumption, we created log-log plots with 95% CIs and the Schoenfeld residual test. The log-log plots are shown in Supplementary Figs. S2 (men) and S3 (women), in which each quartile group is marked by blue (quartile 1), red (quartile 2), pink (quartile 3), and green (quartile 4) in relation to sodium, potassium, and the sodium-potassium ratio. Graphs of each quartile group showed that the 95% CIs overlapped but were parallel. The Schoenfeld residual test and plots showed no significant differences (P < 0.05) for either men (Supplementary Fig. S4) or women (Supplementary Fig. S5). The log-log plots and the Schoenfeld residual test confirmed that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated in our analysis.

DM incidence and density (number of cases per 1,000 person-years) were calculated for each group. Person-years were calculated from the first visit between March 2011 and December 2012 to the last visit or the occurrence of DM in 2013–2018. The P for trend was calculated based on the median of each quartile group for sodium, potassium, and sodium/potassium intakes.

All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and a two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

During a median follow-up of 5.9 years, 3,219 (5.3%) men and 704 (1.8%) women developed DM. Study participants were characterized by relatively young age (39.7 ± 6.9 in men and 38.4 ± 6.5 in women) and a normal BMI (24.4 ± 2.9 in men and 21.5 ± 2.9 in women).

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study participants in relation to the quartiles of sodium intake in men. Groups with higher quartiles of sodium intake had a higher proportion of alcohol intake, were smokers, and had high physical activity. Additionally, potassium intake, the sodium-potassium ratio, dietary fiber intake, and total calorie intake increased with the quartiles of sodium intake. However, fasting glucose, HbA1c, and BMI did not show distinct differences among the quartile groups despite statistical significance (P < 0.05). The incidence of DM was highest in the fourth quartile, followed by the first, second, and third quartiles. The prevalence of prediabetes was 52.4% in men, with quartile 1 showing the highest prevalence.

Women showed findings similar to those in men (Table 2). Potassium intake, sodium-potassium ratio, dietary fiber intake, and total calorie intake increased proportionally with the sodium intake quartiles. No significant differences were observed in the mean values of fasting glucose, HbA1c, or BMI between the quartile groups. The fourth quartile had the highest incidence of DM, followed by the third, first, and second quartiles, respectively. The prevalence of prediabetes was 43.7% in women, and quartile 4 showed the highest prevalence.

Table 3 shows the risk for DM according to the quartile groups of sodium intake, potassium intake, and the sodium-potassium ratio in men. Quartile groups of sodium intake did not show statistically significant findings in the multivariable-adjusted HR and 95% CI for DM (first quartile: reference, second quartile: 0.96 [0.87–1.07], third quartile: 0.94 [0.84–1.05], and fourth quartile: 1.02 [0.89–1.18]). Regarding potassium intake, although the second (0.93 [0.84–1.03]) and third (0.89 [0.79–0.999]) had lower adjusted HRs for DM than the first quartile, wide dispersions of the 95% CIs nullified the statistical significance in the second quartile groups. The sodium-potassium ratio also did not show a significant association with the risk of DM (first quartile: reference, second quartile: 1.06 [0.96–1.18], third quartile: 1.00 [0.90–1.11], and fourth quartile: 1.09 [0.98–1.20]).

These findings were more prominent in women than in men (Table 4). In women, no significant association was observed among quartile groups of sodium intake and the risk of DM (first quartile: reference, second quartile: 0.87 [0.69–1.09], third quartile: 1.02 [0.81–1.29], and fourth quartile: 1.01 [0.7–1.33]). The quartile groups of potassium intake and the sodium-potassium ratio also did not show statistical significance or a specific direction in the association with the HR and 95% CI for DM.

Even after excluding outliers of sodium and potassium intake (1,334 men and 972 women), the adjusted HR and 95% CI for DM did not show a significant association with any quartile groups of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium-potassium ratio in either men (Supplementary Table S1) or women (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

In the present study, high sodium and low potassium intakes were not associated with the risk of developing DM. In men, the quartile groups of sodium intake and the sodium-potassium ratio did not show a significant association with the risk of DM. Although the second, third, and fourth quartiles of potassium intake showed lower HRs for DM than the first, a significant association was observed only in the third quartile. Analysis of women also failed to show any significant association of sodium intake, potassium intake, and the sodium-potassium ratio with the risk of DM. These results suggest that sodium and potassium intakes do not significantly influence the development of DM.

Several studies have suggested that biological phenomena and clinical indices that are seemingly irrelevant to DM can act as potential risk factors23,24. A recent study showed that a non-dipping blood pressure pattern was associated with an approximately 1.5-fold higher risk of new-onset DM in patients with hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea23. Additionally, an increased hepatic steatosis index was associated with a greater risk of type 2 DM in the Chinese population24. Thus, we conducted this study to ascertain whether sodium and potassium intakes are associated with the risk of developing DM. Notably, we found that high sodium and low potassium intakes were not associated with the risk of DM.

Our findings conflict with those of previous studies that investigated the sodium status in patients with DM. In a recent meta-analysis of 43 cross-sectional studies and one cohort study, individuals with DM had higher levels of sodium intake (weighted mean difference: 621.79 mg/day, P< 0.001) and urinary sodium excretion than those without DM14. The frequency of adding salt to foods was proportionally associated with the risk of type 2 DM in the adjusted HR and 95% CI15. Moreover, a significant association between high sodium status and increased risk of DM has been shown in longitudinal investigations. In a prospective study of 1,935 Finnish individuals with a follow-up period of 18 years, elevated 24-hour urinary sodium excretion predicted the risk of type 2 DM, independent of physical inactivity, obesity, and hypertension25. A longitudinal analysis of 5,867 Chinese participants showed that the higher quartile groups (third and fourth quartiles) of sodium intake had a higher risk of DM than the lowest quartile of sodium intake26. Regarding potassium, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study and the Toranomon Hospital Health Management Center Study 1 demonstrated that low serum potassium levels were independent predictors of incident DM during a follow-up of 9 and 5 years, respectively27,28. However, heterogeneous results have been reported when directly analyzing the association of sodium and potassium intake with DM. A meta-analysis of four cross-sectional studies found that high sodium intake was not associated with type 2 DM14. The China Health and Nutrition Survey found no statistically significant association between low dietary potassium intake and risk of diabetes26. Moreover, most of the data were derived from cross-sectional studies, which are not comparable to our study.

Some explanations for the differences in the results between previous studies and ours may exist. For instance, our study participants were characterized by a relatively young age and a normal BMI, which is protective against the development of DM. The overall incidence of DM during the follow-up period was relatively low in men and women. It is presumed that the effect of hazardous factors, including high sodium intake, may be modest in young individuals with normal BMI. Another plausible explanation is the typical major source of sodium intake in the Korean diet. Thus, there may be differences in the sources of sodium intake between Korea and other countries. The major source of sodium intake is pickled seasoned vegetables, such as cabbage, radish, and herbs, which are rich in dietary fiber. Thus, it is likely that a high dietary fiber intake accompanies a high sodium intake. Studies have demonstrated that a high dietary fiber intake protects against the development of DM. A high intake of dietary fiber and a high sodium intake may have a role in reducing the risk of DM29. Lastly, the follow-up period of our study was short, which does not reflect the long-term effects of sodium intake on DM. Our results suggest that the effect of sodium intake on DM can vary depending on age, metabolic condition of the population, source of sodium intake, and follow-up period.

A high sodium intake is associated with a high risk of obesity. In a study conducted in Japan, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States, salt intake was found to be positively associated with BMI and the prevalence of overweight/obesity30. Therefore, the effect of sodium intake on DM has been postulated to be mediated by obesity. Our study also indicated that individuals with a higher sodium intake had a higher total calorie intake. Interestingly, potassium intake increased in proportion to sodium intake. These findings suggest that high intakes of sodium and potassium result from high food consumption. However, our hypothesis was not absolutely dependent on the role of obesity, which mediates the association between high sodium intake and an increased risk of DM. Although individuals with a higher sodium intake had a higher total calorie intake, we hypothesized that other mechanisms contributed to the effect of sodium on the development of DM in addition to obesity. These mechanisms may include inflammatory reactions provoked by sodium intake31and the direct effect of sodium intake on serum insulin concentration or insulin resistance32. The effect of sodium intake on DM may arise not only from obesity related to high sodium intake but also from independent actions of other mechanisms. These actions may trigger the pathophysiological responses related to insulin resistance, resulting in DM. Therefore, we aimed to ascertain the independent role of sodium intake in the risk of DM after adjusting for obesity and total calorie intake. However, we failed to identify a significant association between high sodium intake and an increased risk of DM. Considering the association between DM and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, our findings may explain the results of a previous study where sodium intake and the sodium-to-potassium ratio were not significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Koreans33.

Our study has several limitations. First, our analysis could not adjust for food sources of sodium and potassium intake. Food sources of sodium and potassium are important factors that affect the development of DM. In the present study, sodium and potassium intakes were calculated from 106 food items in the FFQ. Therefore, conducting an adjusted analysis of the 106 items selected by the study participants was not possible. Second, the FFQ is based on the recall of study participants; thus, a possibility of recall bias for sodium and potassium intake exists. Third, we conducted follow-ups for a median period of 5.9 years, which is relatively short for identifying the long-term effects of sodium and potassium intakes on the risk of DM.

In conclusion, sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium-potassium ratio were not associated with the risk of DM in either Korean men or women. This result somewhat contradicts the evidence indicating the harmful effects of high sodium and low potassium intakes on health outcomes. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The study participants were relatively young and had a low incidence of DM. In such participants, sodium and potassium intakes may have a modest effect on the development of DM. Further studies should be conducted in the general population with a longer follow-up period, improved dietary assessment, and diverse populations to identify the effects of sodium and potassium intake on the risk of DM.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study.

References

Noce, A., Romani, A. & Bernini, R. Dietary intake and chronic Disease Prevention. Nutrients 13, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041358 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Optimal dietary patterns for prevention of chronic disease. Nat. Med. 29, 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02235-5 (2023).

Guariguata, L. et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 103, 137–149 (2014).

Diabetes is. A pandemic of unprecedented magnitude now affecting one in 10 adults worldwide. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 181, 109133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109133 (2021).

Lin, X., Wang, S. & Huang, J. The Association between the EAT-Lancet Diet and Diabetes: a systematic review. Nutrients 15, 4462. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204462 (2023).

Lean, M. E. et al. 5-year follow-up of the randomised diabetes remission clinical trial (DiRECT) of continued support for weight loss maintenance in the UK: an extension study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00385-6 (2024).

Forouhi, N. G., Misra, A., Mohan, V., Taylor, R. & Yancy, W. Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. BMJ 361, k2234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2234 (2018).

Wang, Y. J., Yeh, T. L., Shih, M. C., Tu, Y. K. & Chien, K. L. Dietary Sodium Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: a systematic review and dose-response Meta-analysis. Nutrients 12 (10), 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102934 (2020).

Ma, H., Wang, X., Li, X., Heianza, Y. & Qi, L. Adding salt to Foods and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80 (23), 2157–2167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.09.039 (2022).

Liu, W., Zhou, L., Yin, W., Wang, J. & Zuo, X. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease attributable to high sodium intake from 1990 to 2019. Front. Nutr. 10, 1078371. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1078371 (2023).

Evert, A. B. et al. Nutrition Therapy for adults with diabetes or Prediabetes: a Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 42, 731–754. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci19-0014 (2019).

Ekinci, E. I. et al. Dietary salt intake and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 34, 703–709. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1723 (2011).

Thomas, M. C. et al. The association between dietary sodium intake, ESRD, and all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 34, 861–866. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1722 (2011).

Kolahdouz-Mohammadi, R., Soltani, S., Clayton, Z. S. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. Sodium status is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 60, 3543–3565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02595-z (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Dietary sodium intake and risk of Incident Type 2 diabetes. Mayo Clin. Proc. S0025-6196(23)00118-0 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.029 (2023).

Oh, J. Y., Yang, Y. J., Kim, B. S. & Kang, J. H. Validity and reliability of Korean version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form. J. Korean Acad. Fam Med. 28, 532–541 (2007).

Herman, W. H. Prediabetes diagnosis and management. JAMA 329 (14), 1157–1159. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.4406 (2023).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Introduction and methodology: standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 47 (Supplement_1), S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-SINT (2024).

Ahn, Y. et al. Development of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire based on dietary data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr. Sci. 6, 173–184 (2003).

Ahn, Y. et al. Validation and reproducibility of food frequency questionnaire for Korean genome epidemiologic study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 1435–1441. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602657 (2007).

Park, S. K., Chung, Y., Oh, C. M., Ryoo, J. H. & Jung, J. Y. The influence of the dietary intake of vitamin C and vitamin E on the risk of gastric intestinal metaplasia in a cohort of koreans. Epidemiol. Health. 44, e2022062. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2022062 (2022).

Park, S. K. et al. Longitudinal analysis for the risk of depression according to the consumption of sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage in non-diabetic and diabetic population. Sci. Rep. 13, 12901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40194-6 (2023).

Luo, Q. et al. Non-dipping blood pressure pattern is associated with higher risk of new-onset diabetes in hypertensive patients with obstructive sleep apnea: UROSAH data. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1083179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1083179 (2023).

Cai, X. et al. Hepatic steatosis index and the risk of type 2 diabetes Mellitus in China: insights from a General Population-based Cohort Study. Dis. Markers. 2022, 3150380. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3150380 (2022).

Hu, G., Jousilahti, P., Peltonen, M., Lindström, J. & Tuomilehto, J. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study in Finland. Diabetologia 48, 1477–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-1824-1 (2005).

Hao, G. et al. Dietary sodium and potassium and risk of diabetes: a prospective study using data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Diabetes Metab. 46, 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2019.12.002 (2020).

Chatterjee, R. et al. Serum and dietary potassium and risk of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 1745–1751. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.362 (2010).

Heianza, Y. et al. Low serum potassium levels and risk of type 2 diabetes: the Toranomon Hospital Health Management Center Study 1 (TOPICS 1). Diabetologia 54, 762–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-2029-9 (2011).

McRae, M. P. Dietary Fiber intake and type 2 diabetes Mellitus: an Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. J. Chiropr. Med. 17, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2017.11.002 (2018).

Zhou, L. et al. Salt intake and prevalence of overweight/obesity in Japan, China, the United Kingdom, and the United States: the INTERMAP Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110, 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz067 (2019).

Kleinewietfeld, M. et al. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature 496, 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11868 (2013).

Yatabe, M. S. et al. Salt sensitivity is associated with insulin resistance, sympathetic overactivity, and decreased suppression of circulating renin activity in lean patients with essential hypertension. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 92, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.29028 (2010).

Kwon, Y. J., Lee, H. S., Park, G. & Lee, J. W. Association between dietary sodium, potassium, and the sodium-to-potassium ratio and mortality: a 10-year analysis. Front. Nutr. 9, 1053585. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1053585 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was based on medical data collected and arranged by Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study (KSCS). Therefore, this study could be done by virtue of the labor of all staffs working in KSCS and Total Healthcare Center, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital. Additionally, we specially appreciate to prof. Yoosoo Chang in Kangbuk Samsung Cohort team and prof. Mi Kyung Kim in Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Medicine, Hanyang University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sung Keun Park and coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript as a first author. Ju Young Jung and Chang-Mo Oh participated in conducting statistical analysis and writing manuscript. Jae-Hong Ryoo played roles in editing and reviewing manuscript.Ju Young Jung is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approvals for the study protocol and analysis of the data were obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No. KBSMC 2020-09-25). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the IRB of the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. IRB of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved the exemption of informed consent for the study because we only assessed retrospective data with de-identified personal information obtained from routine health check-up.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S.K., Oh, CM., Ryoo, JH. et al. Intake of sodium and potassium, sodium-potassium intake ratio, and their relation to the risk of diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep 15, 4411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88787-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88787-7