Abstract

Color composition is a crucial factor in the aesthetic evaluation of paintings. Several studies have reported a prototype preference for art paintings, where altering the original painting results in a poorer aesthetic evaluation. If the original painting has familiar features, the phenomenon of original preference may be due to the fluency of processing color composition in paintings. However, there are few investigations into the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the preference for original paintings. This study aimed to clarify whether the original preference is due to the fluency of processing color composition using P3 asymmetry to reflect perceptual fluency for stimuli. Oddball tasks with a combination of the original and 180°, or 90° and 270° as control, were performed by swapping the repetitive and deviant stimuli for each task. The results revealed that P3 asymmetry was found only with a combination of 0° and 180°, indicating that the color composition of original paintings can be fluently processed compared with other color compositions in hue-rotated paintings. This explanation may lead to the elucidation of universal color preferences or physiological mechanisms that favor certain color compositions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The paramount criterion for evaluating the aesthetic value of a painting is balanced composition1. Several studies have demonstrated a prototype preference for paintings, with aesthetic evaluations declining when certain elements of the original painting are altered, such as when a realistic painting is transformed into an abstract rendering2, objects within the painting are relocated3, the orientation of the painting is rotated4, and the color gamut of the painting is rotated5. Nascimento et al.5 manipulated preferences by altering only the color composition, defined as the interaction of color combinations and color positions, by rotating the hue around the mean chromaticity of the paintings without changing the spatial features and mean chromaticity. This preference for the original color composition is driven by the perception of naturalness inherent in the composition6. Naturalness is determined by familiarity, defined as the psychological distance between the observer and the object/scene7. Thus, the prototype preference for paintings, as exemplified by color composition, may be attributed to high familiarity with the artwork.

The processing of a stimulus may differ in terms of both velocity and precision contingent upon its inherent attributes; this efficiency is denoted as “fluency.” The preference elicited by familiarity may, in part, be attributable to a misattribution of perceptual fluency8. Familiar stimuli that have been previously exposed are processed with greater fluency than are novel stimuli. This heightened fluency is erroneously ascribed to a preference for the stimulus. Perceptual fluency is one of the components that constitute processing fluency, alongside conceptual fluency. Perceptual fluency refers to the ease with which physical characteristics of stimuli, such as size or shape, are processed. This fluency is influenced by variables such as clarity9, prior exposure8,10, and familiarity11,12 with the stimuli, which relate to the misattribution of perceptual fluency mentioned earlier. Conversely, conceptual fluency refers to the ease with which the meaning of stimuli is processed and is affected by semantic priming13. Reber et al.14 posited the fluency model as a theoretical framework underpinning the formation of aesthetic preferences. They contended that an object’s visual attributes, in conjunction with an individual’s prior exposure to it, modulate its processing fluency, thereby instigating positive emotional responses and facilitating aesthetic evaluations. While several investigations have substantiated an inverted U-shaped relationship between processing fluency and aesthetic preference, additional information, such as the title, style, and description of a painting, can also augment aesthetic preference for stimuli characterized by low processing fluency15,16. The pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking (PIA model), combining the fluency model of aesthetic pleasure14 and dual-process theory from social psychology17, asserts that aesthetic preferences are generated through two distinct processes involved in stimulus processing. Automatic processing depends primarily on the characteristics of the stimuli themselves and remains separate from conscious evaluation. It is linked with the unconscious induction of emotional responses that do not require cognitive resources. Conversely, controlled processing entails purposeful engagement with stimuli, including deliberate analysis and interpretation, which may culminate in the modification of preceding emotional responses18. Within the PIA model, both automatic processing and controlled processing are shaped by perceptual and conceptual fluency. Nevertheless, automatic processing is thought to be more strongly affected by perceptual fluency, whereas controlled processing is more strongly affected by conceptual fluency18. Following the PIA and fluency model of aesthetic pleasure, original painting preferences may be attributed to the processing fluency induced by features inherent in the original works. Given that the preference bias demonstrated by Nascimento et al. with regard to the original color composition5 is elicited despite the absence of any differences in visual features besides the color composition, exploring this bias from a processing fluency perspective may shed light on the mechanism underlying the preference for color composition.

The field of neuroaesthetics, which endeavors to reveal abstract subjective cognitive and affective processes, such as aesthetic preferences, from brain function, was postulated by Zeki19. Since then, several attempts have been made to indirectly investigate the correlation between perceptual/cognitive factors and aesthetic sensations by measuring the brain activities associated with these factors20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Notably, event-related potentials (ERP), which are voltage fluctuations in the electroencephalogram (EEG) that are temporally related to internal or external events, have revealed several components related to aesthetic judgments, including the posterior P2 (peaks in positivity at least 200 ms after the event) associated with the efficient allocation of selective attention resources25, N2 (peaks in negativity at least 200 ms after the event) reflecting processing time for inhibiting responses26, the anterior P2 associated with emotions and arousal25,27, and P3 and late positive potential (LPP) associated with subjective arousal and long-term memory28. The manifestation of the P3 amplitude in response to the oddball paradigm is explained by context-updating theory, which posits that the P3 amplitude is evoked when the memory comparison process in working memory determines whether an input stimulus is the same as a previous stimulus29,30. If the process determines that an input stimulus differs from a previous stimulus, the stimulus representation is updated. Working memory processing performance is poorer with unfamiliar objects than with familiar objects31,32. The difference in P3 amplitude between repetitive and deviant stimuli in the oddball paradigm is greater when the deviant stimulus is more unnatural or unfamiliar than is the repetitive stimulus, for example, when a blue face is the deviant stimulus and a pale-orange face is the repetitive stimulus33,34. Such asymmetry in P3 amplitude is an indicator of processing fluency. Thus, it can be predicted that if the color composition of a painting is fluently processed by an observer, the P3 amplitude will increase when the representation in working memory is updated from the original painting to a hue-rotated painting.

Regarding the study of original color composition preferences, Nakauchi et al.35 demonstrated high-dimensional color characteristics in universally preferred original paintings. Nascimento et al.6 reported that the naturalness of such color compositions drives aesthetic appreciation. Taniyama et al.36 indicated that original painting preferences are judged at relatively early stages, such as automatic processing, as evidenced by changes in pupillary light reflex. Nevertheless, the fundamental reasons behind the preference for paintings with such color characteristics and the perceptions underlying their naturalness assessment remain ambiguous. The color characteristics inherent in the original artwork possesses heightened naturalness. However, as naturalness comprises two dimensions—namely, “closeness to nature” and “familiarity”7—discerning whether this assessment of naturalness is derived from familiarity, closely related to processing fluency, cannot be conclusively determined through behavioral evaluation or pupil measurements, which fluctuate due to various factors. As mentioned previously, the P3 amplitude reflects the difference in naturalness between deviant and repetitive stimuli in the oddball paradigm. Consequently, potential exists to extract processing fluency, derived from naturalness, from the color composition of paintings through EEG measurements.

This study aims to elucidate the processing fluency of color composition in original paintings using P3 asymmetry induced in an oddball paradigm between original and hue-rotated paintings. The hypothesis is that if the color composition of the original paintings possesses high processing fluency, which leads to the perception of naturalness, P3 asymmetry will be observed between the 0° (original) and 180° hue rotation. Conversely, between the 90° and 270° hue rotation, where neither possesses the naturalness of the original painting, P3 asymmetry will not be observed. Additionally, in the experiment by Taniyama et al.36, which used both abstract and representational paintings (flower paintings) to investigate the influence of context within the painting, it was confirmed that pupil constriction occurred when viewing the original paintings, regardless of whether they were abstract or flower paintings. Therefore, in this experiment, it is similarly expected that P3 asymmetry will be observed regardless of the context. As for the behavioral data in the oddball task, higher P3 amplitude has been found to be associated with higher accuracy for target identification in a previous related study37. Hence, when the 180° hue-rotated painting that is predicted to elicit a larger P3 amplitude serves as the target, accuracy is expected to be higher. However, differences in the perceived naturalness or processing fluency of paintings could affect identification accuracy in addition to P3 asymmetry.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-three volunteers participated in the experiment (17 men and six women; age: 20–23 years, mean age: 21.80 years, SD: 0.92). All participants were undergraduate or postgraduate students at Toyohashi University of Technology. The participants were trichromats and had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity. Ishihara plates were used for color vision testing. The participants provided their written informed consent before the experiment. The experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Committee for Human Research of Toyohashi University of Technology.

Stimuli and apparatus

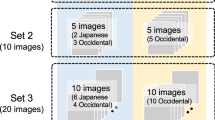

The stimuli comprised 10 abstract and 10 flower paintings, obtained from WikiArt.org (see Table 1). All data related to the paintings are available at WikiArt.org. The reason for using both abstract paintings and flower paintings as stimuli is to examine the influence of context within the paintings. In representational art, such as the flower paintings, recognizable objects are depicted, and elements such as the yellow petals of a sunflower may be influenced by memory colors. In contrast, abstract paintings, containing no recognizable objects, allow for the investigation of the pure effects of color composition alone. Hue-rotated paintings were generated by rotating the chromaticity of the original paintings for each pixel in the CIELAB color space by 90° each, around a line parallel to the L* axis through the mean chromaticity point on the a*–b* plane5,35. The hue-rotated paintings were paired at 180° each (0°–180° and 90°–270°) because the greatest shift on each pixel occurs on the a*–b* plane. In the oddball paradigm, one painting from each pair was presented frequently (standard), whereas the other was presented infrequently (target). The stimuli were resized to the mean area of all paintings while preserving their aspect ratio (mean visual angle (degree): x,y = 6.49, 6.17; SD: x, y = 0.852, 0.876). The mean L* value of all the paintings was 55.68, and raw luminance was 15.96 cd/m2 (SD: L* = 0.576, raw luminance = 0.535 cd/m2). The paintings were presented on a gray background (with the same luminance as that of the paintings, i.e., 15.96 cd/m2). The 80 paintings were divided into two categories (abstract, flower) and four hue angles (0°, 180°, 90°, and 270°), with each category and hue consisting of 10 paintings (total number of stimuli: 80).

EEG measurements were taken in a dark room using a Biosemi 64-channel ActiveTwo system with a sampling frequency of 500 Hz and 64 electrodes. The participants had their heads held steady on a chinrest situated at a viewing distance of 60 cm from the LCD monitor (VIEWPixx, resolution: 1920 × 1200 pixels, frame rate: 120 Hz).

Procedure

The experiment comprised 80 trials, with 10 trials per condition, and a 4:1 ratio of repetitive (standard) to deviant (target) presentations in the oddball task. The frequency of target presentation during the task was randomly determined between 6 and 10 times per trial. The experiment comprised a total of four sessions, with each session consisting of 20 trials. Participants were allowed to take breaks between sessions as needed. Within each session, the 0°−180° and 90°−270° pairs were presented 10 trials each in a random order. The category and target hue within a session remained consistent throughout. The order in which the category and target hue were presented was counterbalanced across participants. None of the paintings were shown to participants prior to the experiment, and no painting was repeated across trials.

Before the task, a fixation point was displayed for 1500 ms. During the task, stimuli were presented for 200 ms, with a 500 ms interval of fixation point presentation between each stimulus. Participants were instructed to fixate on the center of the screen while maintaining a stationary viewpoint. The timing of target stimulus presentation was randomized. Upon completing the oddball task, participants were asked to report the number of target presentations. They were instructed to count the number of other paintings that were not the first painting presented because the target was never presented first. The trial flow is depicted in Fig. 1 and an example stimulus for each condition is presented in Fig. 2.

The experiment in this study includes two conditions: category and target-hue. The former contained two art painting genres, abstract paintings (abstract) and representational paintings (flower). The latter defines which hue-rotated painting is assigned to the target stimulus in the oddball task. For example, when the target hue was 0°, the standard stimulus was set to 180°; conversely, when the target hue was 180°, the standard stimulus was set to 0°.

The experiment was conducted using MATLAB 2019b and Psychtoolbox 338. EEG recordings were obtained throughout the trials, with the analysis focusing exclusively on EEG data collected during the oddball task.

Data analysis

EEG data

Although EEG recordings were obtained continuously throughout the trials, only the EEG data from the presentation of the fixation point to the end of the oddball task were analyzed. EEG signals were filtered between 0.1 and 30 Hz, re-referenced to the average of both earlobes, and interpolated to remove artifacts such as blinks, employing the artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR) method. EEG data were epoched for each stimulus presentation in the oddball task. Subsequently, epochs in which the voltage of the EEG signal exceeded ± 100 µV at any electrode were rejected. The grand average of the epoch rejection rate was 0.104 (SD = 0.117) (the epoch rejection rates for each condition are presented in Supplementary Table 1).

The P3 component of the EEG, measured at the parietal Pz electrode, was analyzed. A − 100 ms to 700 ms interval centered around each stimulus presentation was cut out, with the presentation of each stimulus in a trial during the oddball task assigned a time of 0 ms. Baseline correction was performed by subtracting the averaged amplitude of interval from 100 ms prior to stimulus presentation to 0 ms from the entire interval. The cognitive load that occurred during the context-updating process within the oddball paradigm was quantified by the difference in P3 responses between the target and standard stimuli. To extract the P3 component, we computed the difference by subtracting the averaged standard EEG waveform from the target EEG waveform within each pair condition, followed by taking maximum value from the resulting subtraction waveform within the 330–450 ms time window. We confirmed the presence of P3 asymmetry by comparing components under different conditions. For example, when presenting the 180° hue-rotated painting as the target stimulus with the standard stimulus set at 0°, we calculated the difference as target 180° minus standard 0°.

Accuracy of the target identification data

The accuracy of the identification of the target stimuli in the oddball paradigm was grand-averaged among all participants in each condition. Two participants were excluded from the accuracy analysis because their behavioral data could not be recorded due to data transmission problems.

Statistical analysis

To determine the presence of P3 asymmetry, two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed with the category condition (abstract vs. flower) and target-hue condition (0° vs. 180° or 90° vs. 270°) on the P3 components after subtracting the standard EEG from the target EEG for each 0°–180° and 90°–270° pair. Similarly, for the accuracy data, two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed with the category condition (abstract vs. flower) and target-hue condition (0° vs. 180° or 90° vs. 270°) on the accuracy data for each 0°–180° and 90°–270° pair.

For the two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, a partial eta square was indicated as the effect size. Post hoc comparisons using paired-sample t-tests were conducted for significant factors using ANOVA.

Results

P3 asymmetry by Hue-rotation

Figure 3 depicts the subtraction of the standard EEG from the target EEG in each condition. Figure 4 reveals the results of the inter-participant averages of the maximum values of the differential EEGs shown in Fig. 3 in the 330–450 ms range (P3 difference). Further, the topographs of the P3 differences at each electrode are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Table 2 presents the ANOVA results for Fig. 4, showing a significant difference in the target-hue condition of the 0°–180° pair, \(F\left( {1,22} \right)=7.873,\;~p=0.010,~\;\eta _{p}^{2}=0.264\), and in the category condition of the 0°−180° pair, \(F\left( {1,22} \right)=4.540,~\;p=0.045,\;~\eta _{p}^{2}=0.171\). This result indicates that replacing the target stimulus from the 180° hue-rotated painting to the original painting (0°) in the 0°–180° pair reduced the P3 amplitude difference between the target and standard in both painting categories, confirming the asymmetry of P3 in the 0°–180° pair. However, no significant difference was observed in the target-hue condition of the 90°–270° pair, \(F\left( {1,22} \right)=0.480,~\;p=0.496,~\;\eta _{p}^{2}=0.021.\)

Results of the differential EEGs (target EEG–standard EEG) in abstract in the 0°–180° hue-pair (top-left), abstract in the 90°–270° hue-pair (top-right), flower in the 0°–180° hue-pair (bottom-left), and flower in the 90°–270° hue-pair (bottom-right). The yellow and blue lines represent differential EEG when the target is the original painting (0°) or hue-rotated painting (180°), respectively. The green and red lines represent differential EEG when the target is the 90° or 270° hue-rotated painting, respectively. Shaded regions represent the standard errors in each condition.

The P3 difference (target–standard). The yellow and blue bars represent the P3 difference when the target is the original painting (0°) or hue-rotated painting (180°), respectively. The green and red bars represent the P3 difference when the target is the 90° or 270° hue-rotated painting, respectively. The error bars (black lines) represent the standard error. The asterisk implies a significant difference between levels (\(p<0.05\)).

Accuracy of target identification in the Oddball paradigm

The results of the accuracy of counting the number of target presentations in the oddball paradigm are plotted in Fig. 5. Table 3 presents the ANOVA results for Fig. 5, revealing a significant interaction between the category and target-hue condition in the 0°–180° pair, \(F\left( {1,21} \right)=7.949,\;~p<0.05,\;~\eta _{p}^{2}=0.275\). Simple main effects were observed between categories when the target-hue was 0°, \(F\left( {1,21} \right)=8.670,\;~p<0.01,\;~\eta _{p}^{2}=0.292\), and between 0° and 180° when the category was flower, \(F\left( {1,21} \right)=14.013,~\;p<0.01,~\;\eta _{p}^{2}=0.400\). No significant main effects or interactions were observed in the 90°–270° pair.

The accuracy of target identification. The yellow and blue bars represent the accuracy when the target is the original painting (0°) or hue-rotated painting (180°), respectively. The green and red bars represent the accuracy when the target is the 90° or 270° hue-rotated painting, respectively. The error bars (black lines) represent the standard error. Two asterisks imply significant differences between levels (\(p<0.01\)).

Discussion

This study sought to determine whether the preference for an original painting was due to the high processing fluency with its color composition by using P3 asymmetry. Our findings were as follows: (1) The P3 amplitude difference was significantly larger when the target hue was 180° than when it was 0° (original). However, no significant differences were observed among the 90°–270° pairs, indicating P3 asymmetry only among the 0°–180° pairs. (2) The accuracy of target identification was significantly different only for flower paintings in the 0°–180° pairs, confirming that the accuracy at 0° was higher than that at 180° for the flower paintings but not the abstract paintings.

The P3 asymmetry shown in this study resembles search asymmetry, which involves searching for an outlier—diagonal line as the target—in straight lines. This phenomenon occurs with a shorter response time when the target is represented by a diagonal line39. This arises from the deviation from a standard condition, which can be attributed to the greater prevalence of lines parallel or perpendicular to the ground compared to oblique lines in our daily experiences. The phenomenon of a downward-tilted cube being preferred—referred to as viewing-from-above bias—leads to search asymmetry, as demonstrated by the reduced reaction time when searching for an upward-facing, rather than a downward-facing, cube with its bottom visible40. This bias may arise from the prevalence of objects in daily life being viewed from above, resulting in the formation of an acquired standard. The similarity in color statistics between paintings and natural landscapes41,42 suggests that exposure to color composition contained in numerous original paintings in daily life may form a cognitive bias toward original paintings. Thus, the asymmetry of P3 in the 0°–180° condition may be due to the assumption that the color composition of original paintings represents the standard state.

Perceptual fluency is closely related to stimulus familiarity, with higher perceptual fluency generally leading to higher familiarity9,43,44. The P3 asymmetry between the original and hue-rotated paintings produced in this experiment further supports the theory that familiarity causes the preference for original paintings. P3, induced by the oddball paradigm, is caused by updating representations stored in working memory by the stimuli to which they are exposed (context-updating hypothesis). Working memory capacity is related to the speed of stimulus processing, whereas perceptual fluency reflects processing speed14,45. Working memory processing performance is also higher for familiar objects than for unfamiliar ones32. These findings suggest a difference in familiarity and perceptual fluency between the original and the 180° hue-rotated paintings, providing evidence that original paintings have familiar color compositions.

Regarding the P3 amplitude, when the target hue was 180°, the difference in P3 amplitude increased regardless of the category, whereas the accuracy of target identification was better when the target hue was 0° with only the flower condition. If the P3 amplitude was correlated with oddball task performance, a larger P3 amplitude would result in more accurate discrimination. When a hit occurs, the P3 amplitude is significant, whereas in the case of a miss, it decreases. Additionally, the greater the signal detection sensitivity, represented by d’, the larger the P3 amplitude by target identification in the oddball task37. However, the findings of this experiment revealed a contrasting result, whereby accuracy was lower when the target was at 180° compared to when it was at 0° in the flower condition, and the P3 amplitude was larger for stimuli associated with lower accuracy. This suggests that changes in the P3 amplitude due to decreased processing fluency caused by unnaturalness are more pronounced than in the previously mentioned relationship between task performance and P3 amplitude. Furthermore, the difference in accuracy observed only in the flower condition may reflect the results of a previous study, which revealed that a decrease in naturalness due to hue rotation is more significant in flower than in abstract paintings36. In addition, the opposite relationship between P3 difference and target identification as predicted might be related to differences in the method of target identification in the oddball task. The oddball task in this study requires remembering the number of targets that appeared during the task, rather than responding with a button press when the target is identified46. In other words, working memory resources must be reserved. Kok states that increased memory load in visual search tasks involving memory rehearsal reduces allocable resources and decreases the P3 amplitude elicited by target identification in the visual search task47. Given that P3 is larger when 180° is the target, because more working memory resources are needed to update the representation from 0° to 180°, updating to 180° could lead to working memory overload, making it impossible to allocate resources to the task of counting the number of targets. The main difference between the abstract and flower paintings lies in whether or not there is an identifiable object in the paintings. In the case of flower paintings, there is additional semantic processing, related to the connection between the object and the color, which is probably absent in abstract paintings. The hue-rotated flower paintings require more working memory resources because of the lower conceptual fluency due to the lack of object-color associations.

The P3 difference was significant between categories, with a larger P3 difference in flower paintings than in abstract paintings. Evidence suggests that laypeople tend to pay more attention to details of recognizable objects when viewing representational paintings48. It is also known that the left hemisphere of the brain is superior in processing local features and category judgments, while the right hemisphere is superior in processing global and configural features49,50; further, it has been reported that in preference judgments, preference was enhanced when representational paintings were presented in the right visual field, whereas no such left-right difference was observed for abstract images24. The amplitude of the P3 is known to increase with the difference in perceptual distinctiveness between the target and standard51,52. These results suggest that while flower paintings are affected by the color change between the original and the hue-rotated painting because attention is focused on the flower, abstract paintings are less affected by the color change because local attention is less focused, and the mean chromaticity of the painting does not change between the original and the hue-rotated paintings. Thus, because the difference in perceptual distinctiveness between the standard-target is larger in the flower paintings, the P3 amplitude difference is expected to be larger in these paintings.

A significant P3 asymmetry was found for the 0°–180° pair but not for the 90°–270° pair. This result may be due to the original painting preference, similar to a previous finding that preference was reduced by changing some of the components of the original painting3. The distance in chromaticity moved by each pixel due to hue rotation was the same between the original and the 180° hue-rotated paintings and between the 90° and 270° hue-rotated paintings. In other words, the hue difference of each pixel between the two is the same. Nevertheless, the fact that a difference was observed only in the 0°–180° pair further supports the hypothesis that the original paintings have a familiar color composition. What exactly is a familiar color composition? Although the color statistics of paintings are similar to those of natural scenes41,42, the preferred color composition of paintings is not always similar to that of natural landscapes. Nakauchi and Tamura demonstrated that the preference for paintings can be explained by three color statistics in the LAB color space: skewness a*, correlation a*–b*, and correlation L*–b*53. This study also investigated the correlation coefficients between P3 difference and each color statistic in the 0°−180° hue pairs as additional analysis with single regression. The results showed that correlation a*-b*, skewness b*, and skewness a* were higher, in that order, and correlation a*-b* and skewness a* were consistent with previous studies as variables explaining preference (results of the single regression analysis are presented in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). While these three (skewness a*, correlation a*–b*, and correlation L*–b*) or consistent two color statistics (correlation a*-b* and skewness a*) explaining painting preference are common across painting categories, subjective evaluations such as preference and naturalness, as well as discrimination performance in an oddball task, reveal that the effect of hue rotation is more significant in flower paintings than in abstract paintings36. In this experiment, however, no significant differences were observed in the P3 asymmetry of the 0°–180° pair between abstract and flower paintings. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in pupillary constriction by hue rotation between the abstract and flower paintings36. These findings suggest that physiological responses reflecting automatic processing in the PIA model, such as the pupillary light reflex36 and P3 asymmetry, reflect preference judgments toward familiar color compositions present in original paintings, irrespective of painting categories. Moreover, in behavioral responses that require controlled processing in the PIA model, such as subjective evaluations, there may exist a potential reflection of preference judgments arising from the relationship between objects, such as flowers, and their associated colors (memory color), in addition to the shared color characteristics of paintings.

The number of stimuli used in the psycho-physiological experiment was limited due to the load on the participants. Therefore, it was difficult to analyze color statistics because the sample was small. However, the results of this study, which revealed that the color composition preference of paintings could be explained by an implicit familiarity index called P3 asymmetry, suggest that combining the previous findings that several color statistics and visual characteristics can explain the preference for paintings, with this study, which investigates the factors of preference for paintings from a physiological aspect, may improve the understanding of universal color composition preference and the physiological mechanisms by which these colors are preferred. Consequently, evaluations related to color composition, which have relied predominantly on hue and contrast so far, can now incorporate physiological indicators alongside behavioral data. Moreover, by generalizing this evaluative methodology to be accessible not only to specialists for visual design but also to amateurs, it holds promise as a means to support individuals lacking in aesthetic sense.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study included in this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tatarkiewicz, W. A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Hekkert, P. & Van Wieringen, P. C. W. The impact of level of expertise on the evaluation of original and altered versions of post-impressionistic paintings. Acta Psychol. 94, 117–131 (1996).

Francuz, P., Zaniewski, I., Augustynowicz, P., Kopiś, N. & Jankowski, T. Eye movement correlates of expertise in visual arts. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 87 (2018).

Johnson, M. G., Muday, J. A. & Schirillo, J. A. When viewing variations in paintings by Mondrian, aesthetic preferences correlate with pupil size. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat Arts. 4, 161–167 (2010).

Nascimento, S. M. C. et al. The colors of paintings and viewers’ preferences. Vis. Res. 130, 76–84 (2017).

Nascimento, S. M. C., Marit Albers, A. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Naturalness and aesthetics of colors—preference for color compositions perceived as natural. Vis. Res. 185, 98–110 (2021).

Siipi, H. Dimensions of naturalness. Ethics Environ. 13, 71–103 (2008).

Bornstein, R. F. & D’Agostino, P. R. Stimulus Recognition and the Mere exposure effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 545–552 (1992).

Whittlesea, B. W. A., Jacoby, L. L. & Girard, K. Illusions of immediate memory: evidence of an attributional basis for feelings of familiarity and perceptual quality. J. Mem. Lang. 29, 716–732 (1990).

Jacoby, L. L. & Whitehouse, K. An illusion of memory: false recognition influenced by unconscious perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 118, 126–135 (1989).

Whittlesea, B. W. & Williams, L. D. Why do strangers feel familiar, but friends don’t? A discrepancy-attribution account of feelings of familiarity. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 98, 141–165 (1998).

Birch, S. A. J., Brosseau-Liard, P. E., Haddock, T. & Ghrear, S. E. A curse of knowledge in the absence of knowledge? People misattribute fluency when judging how common knowledge is among their peers. Cognition 166, 447–458 (2017).

Lee, A. Y. & Labroo, A. A. The effect of conceptual and perceptual fluency on brand evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 41, 151–165 (2004).

Reber, R., Schwarz, N. & Winkielman, P. Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8, 364–382 (2004).

Leder, H., Carbon, C. C. & Ripsas, A. L. Entitling art: influence of title information on understanding and appreciation of paintings. Acta Psychol. 121, 176–198 (2006).

Belke, B., Leder, H. & D Augustin, M. Mastering style. Effects of explicit style-related information, art knowledge and affective state on appreciation of abstract paintings. Psychol. Sci. Q. 48, 115 (2006).

Strack, F. & Deutsch, R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8, 220–247 (2004).

Graf, L. K. M. & Landwehr, J. R. A dual-process perspective on fluency-based aesthetics: the pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 19, 395–410 (2015).

Zeki, S. Art and the brain. J. Conscious. Stud. 6, 76–96 (1999).

Kawabata, H. & Zeki, S. Neural correlates of beauty. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 1699–1705 (2004).

Cela-Conde, C. J. et al. Activation of the prefrontal cortex in the human visual aesthetic perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 6321–6325 (2004).

Calvo-Merino, B., Jola, C., Glaser, D. E. & Haggard, P. Towards a sensorimotor aesthetics of performing art. Conscious. Cogn. 17, 911–922 (2008).

Ishizu, T. & Zeki, S. Toward a brain-based theory of beauty. PLoS One 6, e21852 (2011).

Nadal, M., Schiavi, S. & Cattaneo, Z. Hemispheric asymmetry of liking for representational and abstract paintings. Psychon Bull. Rev. 25, 1934–1942 (2018).

Righi, S., Gronchi, G., Pierguidi, G., Messina, S. & Viggiano, M. P. Aesthetic shapes our perception of every-day objects: an ERP study. New. Ideas Psychol. 47, 103–112 (2017).

Carbon, C. C., Faerber, S. J., Augustin, M. D., Mitterer, B. & Hutzler, F. First gender, then attractiveness: indications of gender-specific attractiveness processing via ERP onsets. Neurosci. Lett. 686, 186–192 (2018).

Wang, X., Huang, Y., Ma, Q. & Li, N. Event-related potential P2 correlates of implicit aesthetic experience. Neuroreport 23, 862–866 (2012).

Else, J. E., Ellis, J. & Orme, E. Art expertise modulates the emotional response to modern art, especially abstract: an ERP investigation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 1–18 (2015).

Donchin, E. & Coles, M. G. H. Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behav. Brain Sci. 11, 357–374 (1988).

Polich, J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin. Neurophysiol. 118, 2128–2148 (2007).

Anaki, D. & Bentin, S. Familiarity effects on categorization levels of faces and objects. Cognition 111, 144–149 (2009).

Jackson, M. C. & Raymond, J. E. Familiarity enhances visual working memory for faces. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 34, 556–568 (2008).

Minami, T., Goto, K., Kitazaki, M. & Nakauchi, S. Asymmetry of P3 amplitude during oddball tasks reflects the unnaturalness of visual stimuli. Neuroreport 20, 1471–1476 (2009).

Cycowicz, Y. M. & Friedman, D. Visual novel stimuli in an ERP novelty oddball paradigm: effects of familiarity on repetition and recognition memory. Psychophysiology 44, 11–29 (2007).

Nakauchi, S. et al. Universality and superiority in preference for chromatic composition of art paintings. Sci. Rep. 12, 4294 (2022).

Taniyama, Y., Suzuki, Y., Kondo, T., Minami, T. & Nakauchi, S. Pupil dilation is driven by perceptions of naturalness of color composition in paintings. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat Arts https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000580 (2023).

Nieuwenhuis, S., Aston-Jones, G. & Cohen, J. D. Decision making, the P3, and the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Psychol. Bull. 131, 510–532 (2005).

Kleiner, M., Brainard, D. & Pelli, D. What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3? Perception 36, 1 (2007).

Treisman, A. & Gormican, S. Feature analysis in early vision: evidence from search asymmetries. Psychol. Rev. 95, 15–48 (1988).

von Grünau, M. & Dubé, S. Visual search asymmetry for viewing direction. Percept. Psychophys. 56, 211–220 (1994).

Graham, D. J. & Redies, C. Statistical regularities in art: relations with visual coding and perception. Vis. Res. 50, 1503–1509 (2010).

Montagner, C., Linhares, J. M. M., Vilarigues, M. & Nascimento, S. M. C. Statistics of colors in paintings and natural scenes. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 33, A170–A177 (2016).

Johnston, W. A., Dark, V. J. & Jacoby, L. L. Perceptual fluency and recognition judgments. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 11, 3–11 (1985).

Lanska, M., Olds, J. M. & Westerman, D. L. Fluency effects in recognition memory: are perceptual fluency and conceptual fluency interchangeable? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 40, 1–11 (2014).

Ackerman, P. L., Beier, M. E. & Boyle, M. O. Individual differences in working memory within a nomological network of cognitive and perceptual speed abilities. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 131, 567–589 (2002).

Ritter, W. & Vaughan, H. G. Jr. Averaged evoked responses in vigilance and discrimination: a reassessment. Science 164, 326–328 (1969).

Kok, A. On the utility of P3 amplitude as a measure of processing capacity. Psychophysiology 38, 557–577 (2001).

Vogt, S. & Magnussen, S. Expertise in pictorial perception: eye-movement patterns and visual memory in artists and laymen. Perception 36, 91–100 (2007).

Hübner, R. Hemispheric differences in global/local processing revealed by same-different judgements. Vis. Cogn. 5, 457–478 (1998).

Robertson, L. & Lamb, M. Neuropsychological contributions to theories of part/whole organization. Cogn. Psychol. 23, 299–330 (1991).

Katayama, J. & Polich, J. Stimulus context determines P3a and P3b. Psychophysiology 35, 23–33 (1998).

Comerchero, M. D. & Polich, J. P3a and P3b from typical auditory and visual stimuli. Clin. Neurophysiol. 110, 24–30 (1999).

Nakauchi, S. & Tamura, H. Regularity of colour statistics in explaining colour composition preferences in art paintings. Sci. Rep. 12, 14585 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grants JP19H01119 and JP20H05956) and the Program for Leading Graduate Schools at Toyohashi University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. wrote the manuscript and performed the experiments. Y.T., Y.N., and T.M. conceived the experiments. Y.T. and Y.N. analyzed the results. S.N. and T.M. supervised the experiments and discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taniyama, Y., Nihei, Y., Minami, T. et al. Natural color composition induces oddball P3 asymmetry associated with processing fluency. Sci Rep 15, 4878 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88815-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88815-6