Abstract

To analyze the correlation between the main perfusion parameters of the left ventricle and various physiological and coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors or comorbidities using dynamic stress computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (CT-MPI) in patients without obstructive coronary stenosis. This retrospective analysis included 119 patients without obstructive coronary artery stenosis in computed tomography angiography (CTA), and without perfusion defects in CT-MPI. Patients were categorized into groups based on the presence or absence of physiological and CAD risk factors or comorbidities. The global myocardial blood flow (MBF), myocardial blood volume (MBV), and perfused capillary blood volume (PCBV) of the left ventricle were compared between groups, and correlations with continuous variables were analyzed. Multivariate linear regression was used to identify independent factors. Perfusion parameters were higher (MBF, 149.41 ± 26.38 vs. 159.20 ± 21.31 ml/100 ml/min, MBV, 17.09 ± 2.37 vs.18.84 ± 1.89, and PCBV, 9.82 ± 2.21 vs. 11.47 ± 1.79 ml/100 ml [all P < 0.05]) in female patients than in male patients. Hypertension and overweight/obesity resulted in lower perfusion parameters (hypertension vs. normotension: MBF, 148.09 ± 21.15 vs. 161.47 ± 25.13 ml/100 ml/min, PCBV, 10.25 ± 2.23 vs. 11.22 ± 1.96 ml/100 ml; overweight/obesity vs. none: MBF, 148.82 ± 20.98 vs. 159.51 ± 25.44 ml/100 ml/min, PCBV, 10.20 ± 1.93 vs. 11.15 ± 2.22 ml/100 ml [all P < 0.05]). Body surface area (BSA), body mass index, stress heart rate (HR), incremental HR, coronary total plaque volume, and stress systolic blood pressure were significantly correlated with perfusion parameters (all P < 0.05). Stress HR, BSA, and hypertension were independent predictors of MBF, stress HR and sex were independent predictors of MBV, and stress HR and BSA were independent predictors of PCBV. Dynamic stress CT-MPI myocardial perfusion is affected by stress HR, sex, and BSA, and can identify early perfusion distribution in hypertension and obesity/overweight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (CT-MPI) is a noninvasive functional method used to assess myocardial perfusion under pharmacological stress1. Experts widely agree on the effectiveness of CT-MPI in detecting myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) based on clinical trials2,3,4. The precise quantification of myocardial perfusion, such as myocardial blood flow (MBF), using CT-MPI can aid in diagnosing myocardial ischemia in patients with obstructive CAD and coronary microvascular dysfunction5,6,7,8,9,10. In clinical practice, the quantitative parameters of CT-MPI in patients without hemodynamically significant ischemia widely vary, leading to confusion in the interpretation of perfusion.

Myocardial perfusion is a complex physiological process influenced by multiple pathways. Previous studies have focused on the distribution and influence of physiological factors on perfusion in normal healthy individuals11,12,13,14. Based on positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), normal perfusion shows significant variation and is related to physiological factors, such as age and sex11,12. Studies using CT-MPI have reported the distribution of MBF in healthy individuals13,14. However, in clinical practice, patients suspected of myocardial ischemia are always associated with CAD risk factors or comorbidities, such as hypertension (HP) or diabetes, and myocardial perfusion may already be compromised by CAD risk factors in the microvasculature7,8,9,15,16. In a real patient population, the effects of physiological factors and CAD risk factors on myocardial perfusion in stress CT-MPI remain inadequately understood9. Understanding the correlation between perfusion and physiological or CAD risk factors or comorbidities in patients without obstructive coronary stenosis using CT-MPI is essential. This knowledge is valuable for interpreting perfusion results, optimizing perfusion scanning15,16. In light of this, our study aimed to evaluate the correlation between perfusion parameters and physiological and CAD risk factors or comorbidities in patients without obstructive coronary stenosis using CT-MPI, ultimately contributing to a better understanding of myocardial perfusion in patients without hemodynamically significant ischemia.

Results

study population

Among the 169 patients with coronary artery stenosis < 50%, 50 were excluded, including 6 with stent implantation, 5 with a history of infarction, 8 with structural heart disease, 5 with myocardial hypertrophy, 16 with local decreased MBF value caused by deep bridge vessel, 10 with unqualified CTP image quality, 10 with incomplete information on risk factors. A total of 119 patients were included in this study. The Likert scores for the image quality of CT-MPI were as follows: 4 for 90 patients, 3 for 24 patients, 2 for 5 patients, and 1 for 10 patients (who were excluded). The radiation exposure during CT-MPI was 276.51 ± 95.28 mGy*cm, equivalent to 7.19 ± 2.45 mSv. All patients tolerated stress CT-MPI well.

In total, 119 patients, 53 (44.54%) males; mean age, 69.58 ± 5.93 years; and average BMI, 25.03 ± 16.99 kg/m2 ); 59 (49 .58%) patients had HP, 32 (26.89%) were diagnosed with diabetes, 25 (21.01%) had hyperlipidemia, and 29 (24.37%) reported a history of smoking. Only 7 (5.88%) patients had a family history of CAD; this number was significantly small to be analyzed.

On CCTA images, 47 (39.49%) patients had minimal stenosis (1–24%) and 34 (28.57%) had mild stenosis; the Agatston CACS was 0 (0–69.96), and coronary TPV was 26.41 (0–127.72). On CT-MPI images, the global MBF (ml/100 ml/min), MBV (ml/100 ml), and PCBV (ml/100 ml) of the patients were 154.84 ± 24.10 (range, 101.06–235.55), 18.06 ± 2.28 (range, 12.08–23.16), and 10.74 ± 2.14 (range, 3.95–15.61), respectively. During the scanning, the rest and stress HRs (bpm) were 76.84 ± 12.77 and 90.87 ± 30.69, respectively. The rest and stress systolic BPs (SBPs, mmHg) were 136.12 ± 15.69 and 124.82 ± 13.49, respectively, and the diastolic BPs (DBPs, mmHg) were 84.10 ± 12.33 and 77.46 ± 11.17, respectively. The characteristics of the study population are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Univariate analysis

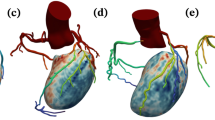

The patients were categorized into groups based on physiological factors and the presence or absence of CAD risk factors or comorbidities. Within the groups analyzed, MBF and PCBV showed similar statistical differences. The global MBF (ml/100 ml/min), MBV, and PCBV (ml/100 ml) in females were significantly higher than those in males (159.20 ± 21.31 vs. 149.41 ± 26.38 [P = 0.031], 18.84 ± 1.89 vs. 17.09 ± 2.37 [P < 0.001], and 11.47 ± 1.79 vs. 9.82 ± 2.21 [P < 0.001], respectively). Patients with HP and overweight/obesity had significantly lower MBF and PCBV compared with those without (HP and without HP: MBF, 148.09 ± 21.15 vs. 161.47 ± 25.13 ml/100 ml/min [P = 0.002]; PCBV, 10.25 ± 2.23 vs. 11.22 ± 1.96 ml/100 ml [P =0.013], respectively; overweight/obesity vs. without overweight/obesity: MBF, 148.82 ± 20.98 vs. 159.51 ± 25.44 ml/100 ml/min [P = 0.016], PCBV, 10.20 ± 1.93 vs. 11.15 ± 2.22 ml/100 ml [P = 0.014], respectively). No significant differences were observed among the other groups (all P > 0.05). The results are shown in Table 3; Figs. 1, 2 and 3, and illustrations of typical cases are displayed in Fig. 4.

Global MBF was positively and weakly correlated with stress HR (r = 0.352, P < 0.001) and HR increment (r = 0.322, P = 0.0036) and weakly correlated with rest HR, BSA, BMI, and TPV (0 < r < 0.3, all P < 0.05). Global MBV was weakly correlated with BAS, BMI, stress HR, TPV, rest SBP, and stress SBP (0 < r < 0.3, all P < 0.05). Global PCBV was weakly correlated with BSA (–0.372, P < 0.001), stress HR (r = 0.385, P < 0.001), and TPV (r=–0.351, P < 0.001) and weakly correlated with rest HR and increment HR (0 < r < 0.3, all P < 0.05). No correlations were found between perfusion parameters and age, rest HR, LVM, LVMI, and CACS score (all P > 0.05). No correlations were found between age, LVM, LVMI, CACS, and BPs (all P > 0.05). The correlation matrix was presented in Fig. 5, with significant factors specifically highlighted using colors to indicate the strength and direction of the correlations. The r and P values results are listed in Table 4.

Correlation matrix for continuous variables with significant correlations (P < 0.05). The strength and direction of the correlations are represented by the colors and sizes of the tiles. Positive correlations are shown in blue, whereas negative correlations are depicted in red, with darker colors indicating stronger relationships.

multivariate linear regression

In assessing the dependent factors for MBF, the following univariates were initially assessed: BSA, BMI, rest and stress HR, sex, HP, incremental HR, and TPV, which were significantly correlated with MBF (all P < 0.05). For HR-related factors, we included all variables in a multivariate regression for MBF and found that only stress HR was independently correlated (P < 0.05). As stress HR was correlated with sex, adjusting for stress HR rendered the relationship between MBF and sex nonsignificant (P = 0.12), whereas stress HR remained highly significant (P < 0.001). For body weight-related factors, BSA and BMI were included, with only BMI emerging as an independent factor. Given the intercorrelation between BSA and HP, we included them in the analysis and found that both remained significant. In the final multivariate linear regression model, HR, BSA, HP, and coronary TPV were included. Coronary TPV lost significance, leaving three independent predictors (HP, BSA, stress HR) of MBF. The final equation was as follows: MBF = 131.03 − (11.36 × HP) − 23.71 × BSA + 0.62 × stress HR. The adjusted R-squared for this model was 24%.

When assessing the dependent factors for MBV, BSA, stress HR, sex, coronary TPV, and stress SBP were significantly correlated with MBV (all P < 0.05). These significant factors were incorporated into a single model. BSA, coronary TPV, and stress SBP were not significantly correlated, leaving only sex and stress HR independently correlated with MBF. The final equation was as follows: MBV = 113.40 + (1.54 × sex) + (0.04 × stress HR). The adjusted R-squared for this model was 20.3%.

When assessing the dependent factors for PCBV, sex, HP, BSA, BMI, rest and stress HR, incremental HR, coronary TPV, and rest and stress SBP were significantly correlated with PCBV (all P < 0.05). BSA and BMI had similar physiological implications; however, BSA was independently correlated with PCBV. Among various HR parameters, stress HR emerged as an independent factor. When BSA and HP, which were intercorrelated, were included in one model, HP was not statistically significant. Finally, when sex, stress HR, BSA, coronary TPV, and stress SBP were combined into a single model, only BSA and stress HR remained significant. The final equation was as follows: PCBV = 11.95 – (3.88 × BSA) + (0.05 × stress HR). The adjusted R-squared of this model was 24%.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the influence of both physiological and cardiovascular risk factors on stress CT-MPI in patients without significant hemodynamic myocardial ischemia: (1) Stress HR obviously effects the perfusion parameters, was an independent factor of all MBF, MBV, and PCBV. (2) Female patients had significantly higher perfusion values than male patients, with higher stress HR, and sex was an independent predictor of only MBV; (3) Patients with HP and overweight/obesity had significantly lower MBF and PCBV values; HP and BSA were independent predictors of MBF.

Vasodilator stress agents are used during dynamic stress CT-MPI to induce hyperemia. ATP is regularly used instead of adenosine because of its lower costs2. It is widely believed that the intravenous injection of adenosine or ATP reduces cardiac parasympathetic tension and increases sympathetic nerve tension. This leads to an increase in HR, peripheral vascular dilataion, a decrease in BP, and, ultimately, an increase in MBF17,18. An individual’s response to pharmacological stress can affect the level of congestion, which may be influenced by various physiological and pathological factors and can be indicated by an increase in HR18. In our study, stress HR was identified as an independent predictor of three perfusion parameters. These results are consistent with the responses of the stress agents. A decreased BP also predicts the degree of perfusion19. However, we did not observe this effect in our database; The reason may be that we measure the BP in the supine after the scan, which may cause the measurement error.

Global MBF, MBV, and PCBV were significantly lower in males than in females, and sex was an independent predictor of MBV. This sex disparity may be owing to the elevated HR for stress observed in female patients. This result is similar to those of studies on healthy volunteers using CT-MPI12,13. Studies employing CMR16and PET imaging20have reported significant differences in MBF between sexes. A SPECT study suggested that male patients had a diminished HR response to adenosine21. The underlying causes of these sex differences remain uncertain, but can potentially be related to factors, such as estrogen levels affecting coronary artery tone22, increased capillary density in the myocardium of females23, or different responses to stress agents between the sexes21. Brown et al. suggested that females might require more intensive medical treatments and different perfusion thresholds for significant coronary stenosis to improve long-term outcomes than males12.

Based on the above results, to maximize coronary hyperemia and myocardial perfusion, the dose and injection time of stress agents should be adjusted by observing the HR or BP during stress CT-MPI. Yu et al.24recommended an HR increment of at least 20 bpm in CT-MPI as a predictor of a significant increase in global MBF. The use of higher doses or injection rates of stress agents in male patients should also be considered. Some medications and foods also affect perfusion; therefore, these agents need to be discontinued when performing stress CT-MPI to avoid influencing perfusion results1,2,3,25.

The global MBF value was lower than that among healthy volunteers using the same CT scanner, 164 ± 24 (range, 114–228) ml/100 ml/min13. Our study shows that although there is no clear hemodynamic stenosis in the coronary artery, various risk factors lead to a decrease in myocardial perfusion, with HP and BSA being particularly significant.

The global MBF, MBV, and PCBV of LV were significantly lower in patients with HP than in those without HP, and HP was a dependent factor for the three parameters. This result is similar to that of a study by Vliegenthart et al., who reported that patients with HP exhibited lower MBV and Ktrans than those without HP9. In both studies, patients had no left ventricular hypertrophy, suggesting that these parameters can potentially detect perfusion abnormalities before the onset of left ventricular hypertrophy, possibly because of early autonomic dysfunction26. Early assessment of myocardial perfusion in individuals with HP without left ventricular hypertrophy may be possible, which is clinically important for mitigating the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Previous studies had shown that an increased BMI was associated with abnormalities in coronary circulatory function27. In patients with obesity, the coronary coronary flow reserve decreases linearly with increasing BMI28. Our study found that BSA was an independent factor associated with MBF and PCBV, that could more accurately show this influence than BMI. This may be because BMI does not accurately reflect body fat content. A study found that overweight adults had a similar risk of death to individuals of a “normal” weight. Moreover,《nature》 calls for the redefinition of obesity instead of BMI29.

Certainly, plaque assessments and CACS do not rely on false prognostic distinction between obstructive and nonobstructive lesions. TPV was strongly and independently associated with adverse coronary events30. Coronary TPV negatively correlated with MBF, MBV, and PCBV; however, it was not an independent factor. These results showed that in patients without obstructive coronary artery stenosis, plaques did not cause significant hemodynamic changes sufficient to result in a decrease in perfusion.

In our study, we did not find statistically significant differences in perfusion parameters between the groups with respect to diabetes or hyperlipidemia. In addition, no correlation was observed between age groups. Previous studies had reported that these factors affect myocardial perfusion during functional imaging9,12,21. The sample size of patients with diabetes or hyperlipidemia was likely insufficient to detect significant differences.

This study has some limitations. This was a single-center study, and its conclusions are only applicable to scenarios with similar devices and scanning schemes. Second, the different perfusion analysis software used may have affected the perfusion results because of the different specific models analyzed. Additionally, the raw data were processed using a manual splitter, and there may have been potential interoperation bias. Furthermore, no comparative analysis was performed with other noninvasive functional tests, such as stress CMR. Finally, myocardial perfusion is a complex physiological process influenced by multiple pathways, and a well-specified model may not capture all sources of variability. In such cases, a low adjusted R-squared (20.3–24%) reflects the model’s ability to explain part of the variability, especially when dealing with complex cardiovascular interactions, underscoring the importance of future studies to explore other potential contributing factors that were not included in the current model. Further studies with larger sample sizes and a prospective design are required.

This study preliminarily analyzed the influence of physiological and CAD risk factors on perfusion parameters in dynamic stress CT-MPI in patients without coronary obstructive stenosis and local perfusion defects. This study reveals that myocardial perfusion parameters are affected by stress HR, sex, BSA, and can identify early perfusion distribution in patients with hypertension and obesity/overweight.

Methods

study population

This study was approved and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (registration number: 2022 − 357). All CT-MPI and CCTA scanning methods were performed in accordance with the relevant expert consensus by the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT)2. A cohort of adult patients were retrospectively assessed between October 2020 and March 2024.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) suspected CAD following a combined CT-MPI and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) scan and (2) patients without obstructive coronary stenosis, which is defined as less than 50% narrowing of their coronary arteries confirmed by CCTA4. The following patients were excluded from this study: (1) patients with a history of ischemia, myocardial infarction, and revascularization, including interventional therapy or coronary artery bypass surgery; (2) patients with concomitant or structured heart disease, such as left ventricual hypertrophy, cardiomyopathy, or heart dysfunction; (3) patients with significant localized absolute MBF values < 100 ml/100 ml/min or relative MBF ratios < 0.667, based on the conclusions of previous studies31,32; (4) patients with nondiagnostic quality of CT-MPI images; and (5) patients with incomplete clinical information. A flowchart of the inclusion process is shown in Fig. 6.

image scan

Preparation: The following medications were discontinued 24–48 h before the examination: beta-blockers, nitrates, calcium antagonists, dipyridamole, and aminophylline. Caffeinated beverages and foods, such as coffee and cola, were also not consumed within 24 h preceding the examination2,3. Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring leads were attached to monitor the patients throughout the examination. Blood pressure (BP, mmHg) and heart rate (HR, beats per minute [bpm]) were assessed, and detailed process instructions and repeated breathing exercises were performed, in order to reduce motion artifacts during the scan. Two 18-gauge cannulas were inserted into the antecubital vein.

Equipment and process:

CT scans were performed using a third-generation dual-source CT system (Somatom Force; Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). The coronary artery calcification score (CACS) was calculated using a plain scan of the heart followed by a CT-MPI scan covering the entire left ventricle (LV). Finally, CCTA was performed.

Computed tomography-myocardial perfusion imaging scanning: Adenosine disodium triphosphate (ATP) was intravenously injected at a rate of 0.14 mg/kg/min to induce coronary artery dilatation, followed by 40–48 ml of iodized contrast medium (Iodomyron, 400 mg/ml, Bolecco, Italy) at a rate of 5–6 ml/s at the end of the 3rd minute, and the duration of injection was 8 s, followed by 40 ml of normal saline at the same rate3. The scan trigger delay was 4 s, and scanning was performed using the shuttle-mode acquisition technique at the end of systole (250 ms after the R-wave) for a total scan time of 32 s. The patients were closely monitored for safety during scanning, and ATP injection was immediately discontinued upon completion. CARE Kv and CARE DOSE 4D were programmed to automatically modify the tube voltage and current according to the designated settings: a reference tube voltage of 80 kV, reference tube current of 300 mAs, rotation time of 0.25 s per cycle, collimation of 48 × 1.2 mm, and layer thickness and increment of 3 mm and 2.9 mm, respectively. All patients were sublingually administered nitroglycerin 5–10 min after the CT-MPI scan. Subsequently, CCTA was performed.

Coronary computed tomography angiography scanning:

A prospective ECG-triggered acquisition method was applied, which involved the administration of 40–60 ml of iodized contrast medium (Iodomyron, 400 mg/ml, Bolecco, Italy) at a flow rate of 4–6 ml/s. This was immediately followed by the injection of 40 ml of normal saline. The utilization of trigger scanning technology allowed for the precise setting of the trigger level at the ascending aorta, with a defined threshold of 100 Hounsfield units. The scan commenced automatically after a waiting period of 5 s. The reference tube voltage was set to 100 kV, utilizing CARE DOSE 4D technology to enable automatic current regulation at 320 mA. The scanning procedure involved a rotation time of 0.25 s per cycle and collimation dimensions of 192 mm × 0.6 mm. Data reconstruction was performed using a Bv40 reconstruction kernel with a layer thickness of 0.75 mm and in increment of 0.5 mm.

image processing

CT-MPI images were reconstructed using Qr36 and transferred to the myocardial perfusion analysis software (Syngo.via, Siemens Healthineers). Data for respiratory movement, noise reduction, and myocardial segmentation were manually adjusted. The MBF, myocardial blood volume (MBV), and perfused capillary blood volume (PCBV) were quantified using a hybrid deconvolution model. The automatic generation and evaluation of perfusion images were conducted using a Likert scoring system to assess quality. Presence of motion artifacts was evaluated in the 16 segments of the LV causing perfusion image dislocation, with scores of 0–4 based on the following criteria: an artifact-free segment percentage of ≥ 90%, score of 4; ≥ 80%, score of 3; ≥ 70%, score of 2; ≥ 60%, score of 1; and ≥ 50%, score of 0, with scores of 2–4 considered acceptable. Subsequently, the qualified perfusion images were transferred to the Cardiac Function Analysis software (Siemens Healthineers, version 2.0.5), which produced a color-coded polar map of the MBF. This map allows for the direct display of MBF values for any area that the mouse pointer hovers over. Patients with MBF values < 100 ml/100 ml/min were considered myocardial ischemia, and were excluded. The global MBF, MBV, and PCBV of the entire LV were automatically calculated using myocardial perfusion analysis software for the included cases.

For CCTA images, the diastolic CCTA images were imported into the coronary analysis workstation (Shukun, China). The severity of stenosis in the left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary arteries were assessed according to the guidelines provided by the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography4, and the CACS as well as the coronary total plaque volume (TPV) were calculated for all coronary arteries. The diastolic CCTA images were imported into the cardiac function software (Syngo.via, Siemens Healthineers) to automatically calculate the LV mass (LVM, g) and LVM index (LVMI) = (LVM/body surface area [BSA], g/m2).

CT-MPI and CCTA results were evaluated by two cardiac radiologists blinded to the patient data. Conflicts were resolved through discussion with an additional senior cardiologist specializing in radiology with > 15 years of experience.

information collection

Patient information, including age, sex, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), BSA, and CAD risk factors, were obtained from the Picture Archiving and Communication System. BMI and BSA were calculated by height and weight, and patients with BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2were considered overweight and obesity33. The diagnosis of comorbidities were established by clinicians according to the following criteria: HP, BP ≥ 140/90 mm Hg34; diabetes, fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7 mmol/L or 2 h after loading or random blood glucose level ≥ 11.1 mmol/L or hemoglobin A1c level ≥ 6.5%35; and hyperlipidemia, with one of the following conditions: triglyceride level ≥ 2.3 mmol/L, total cholesterol level ≥ 6.2 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level ≥ 4.1, or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level < 1.0 mmol/L36. Smoking history (past or current smoking) and family history of CAD (first-degree relative, parent, sibling, or child, have coronary heart disease at age < 50 years) were reported by the patients themselves.

Rest and stress HR and HR increments (calculated as stress HR minus rest HR) were documented according to the ECG recordings. Rest and stress BP were collected before and after stress CT-MPI. The CT-MPI dose-length products were documented. The effective radiation dose (mSv) was calculated as the product of dose length multiplied by a conversion factor (k = 0.026, msv.mgy–1.cm–1)37.

statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26.0, IBM) and MedCalc software package (version 15.2.0). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages (%), whereas continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations or as medians with interquartile ranges. First, we performed a univariate analysis to identify variables that had a statistically significant correlation with MBF, MBV, and PCBV. For categorical variables, differences between groups were assessed using t-tests or nonparametric tests. For continuous numerical variables, pairwise correlations were assessed using Pearson or Spearman tests, depending on the distribution (normal or non-normal as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test), to generate a correlation matrix with corresponding P-values. For categorical variables, differences in perfusion parameters (MBF, MBV, PCBV) between the groups were evaluated using t-tests or nonparametric tests, as appropriate. Variables that showed significant correlations (P < 0.05) in the univariate analyses were selected for further analysis.

To ensure a more systematic approach and to avoid arbitrary inclusion of variables, we grouped significant variables based on their physiological or clinical relevance. Subsequently, we tested for correlations between variables within each group to identify potential multicollinearity or relationships that could suggest one variable might confound the effect of another. In instances where two variables within a group were strongly correlated, we first applied multivariate tests to determine which variables exhibited independent significance. After refining the variables within each group, we combined them into a final multivariate model to account for potential confounding across groups. A two-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Seitun, S. et al. Stress computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging: a new topic in cardiology. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 69, 188–200 (2016).

Patel, A. R. et al. Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography expert consensus document on myocardial computed tomography perfusion imaging. J. Cardio Vasc Comput. Tomogr. 14, 87–100 (2020).

Sliwicka, O. et al. Dynamic myocardial CT perfusion imaging—state of the art. Eur. Radiol. 33 (8), 5509–5525 (2023).

Cury, R. C. et al. CADRADSTM 2.0–2022 coronary artery disease-reporting and data system: an expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the North America Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 16 (6), 536–557 (2022).

Nous, F. M. A. et al. Dynamic myocardial perfusion CT for the detection of hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 15 (1), 75–87 (2022).

Meinel, F. G. et al. Global quantification of left ventricular myocardial perfusion at dynamic CT: feasibility in a multicenter patient population. Am. J. Roentgenol. 203 (2), W174–W180 (2014).

Yu, Y. et al. Microvascular myocardial ischemia in patients with diabetes without obstructive coronary stenosis and its Association with Angina. Korean J. Radiol. 24 (11), 1081–1092 (2023).

Tomizawa, N. et al. Longer diabetes duration reduces myocardial blood flow in remote myocardium assessed by dynamic myocardial CT perfusion. J. Diabetes Complications. 32 (6), 609–615 (2018).

Vliegenthart, R. et al. Dynamic CT myocardial perfusion imaging identifies early perfusion abnormalities in diabetes and hypertension: insights from a multicenter registry. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 10 (4), 301–308 (2016).

Kong, W. F. et al. Diagnostic efficacy of absolute and relative myocardial blood flow of stress dynamic CT myocardial perfusion for detecting myocardial ischemia in patients with hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1398635 (2024).

Wang, L., Jerosch-Herold, M., Jacobs, D. R. Jr, Shahar, E. & Folsom, A. R. Coronary risk factors and myocardial perfusion in asymptomatic adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47 (3), 565–572 (2006).

Brown, L. A. E. et al. Sex- and age-specific normal values for automated quantitative pixel-wise myocardial perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 24 (4), 426–434 (2023).

Lyu, L. J. et al. Knowledge of hyperemic myocardial blood flow in healthy subjects helps identify myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 3 (9), 817911 (2022).

Møller, M. B. et al. Normal values of myocardial blood flow measured with dynamic myocardial CT perfusion. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 25 (7), 986–995 (2024).

Székely, A. et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion should be interpreted in the light of sex and comorbidities in patients with suspected chronic coronary syndrome: a cardiac positron emission tomography study. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging. 44 (1), 89–99 (2024).

Mygind, N. D. et al. Coronary microvascular function and Cardiovascular Risk factors in women with Angina Pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: the iPOWER Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 (3), e003064 (2016).

Nguyen, K-L. et al. Safety and tolerability of regadenoson CMR. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 15, 753–760 (2014).

Karamitsos, T. D. et al. Feasibility and safety of high-dose adenosine perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 12 (1), 66 (2010).

Kramer, C. M. et al. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) protocols: 2020 update. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 22, 17 (2020).

Chareonthaitawee, P., Kaufmann, P. A., Rimoldi, O. & Camici, P. G. Heterogeneity of resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in healthy humans. Cardiovasc. Res. 50 (1), 151–161 (2001).

Gebhard, C. et al. Sex and age differences in the association of heart rate responses to adenosine and myocardial ischemia in patients undergoing myocardial perfusion imaging. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 27 (1), 159–170 (2020).

Collins, P. et al. 17 beta-estradiol attenuates acetylcholine-induced coronary arterial constriction in women but not men with coronary heart disease. Circulation 92 (1), 24–30 (1995).

Miller, V. M. Gender and vascular reactivity. Lupus 8, 409–415 (1999).

Yu, L., Tao, X., Dai, X., Liu, T. & Zhang, J. Dynamic CT myocardial perfusion imaging in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: quantification of myocardial blood Flow according to Varied Heart Rate increments after stress. Korean J. Radiol. 22 (1), 97–105 (2021).

Lassen, M. L. et al. Sex differences and caffeine impact in adenosine-induced hyperemia. J. Nucl. Med. 63 (3), 431–437 (2022).

Palatini, P. & Julius, S. The role of cardiac autonomic function in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 11 (3), 199–205 (2009).

Valenta, I., Upadhyaya, A., Jain, S. & Schindler, T. H. PET/CT Assessment of Flow-mediated epicardial vasodilation in obesity and severe obesity. JACC Adv. 3 (5), 100936 (2024).

Bajaj, N. S. et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Risk in obese patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72 (7), 707–717 (2018).

Prillaman, M. Why BMI is flawed - and how to redefine obesity. Nature. 622(7982), 232–233 (2023).

Kwiecinski, J. et al. Noninvasive coronary atherosclerotic plaque imaging. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 16 (12), 1608–1622 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Clinical outcomes of dynamic computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging combined with coronary computed tomography angiography versus coronary computed tomography angiographyguided strategy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 13 (1), e009775 (2020).

Kong, W. F. et al. Diagnosing myocardial ischemia of obstructive coronary artery disease using dynamic computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging: optimization of relative myocardial blood flow ratio. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 40 (12), 2481-2490 (2024).

Working Group on Obesity of Chin. Guidelines for adult overweight and obesity control in China. Acta Nutrimenta Sinica. 26 (1), 1–4 (2004).

Mancia, G. et al. 2023 ESH guide⁃lines for the management of arterial hypertension the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 41 (12), 1874–2071 (2023).

Compilation group of《Clinical Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of. Type 2 diabetes in the Elderly in China》. Clinical guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of type 2 diabetes in China (2022 edition). Chin. J. Diabetes. 30 (01), 2–51 (2022).

Joint Committee on the Chinese guidelines for lipid management. Chinese guidelines for lipid management. Chin. Circulation J. 38 (3), 0237–0235 (2023).

Trattner, S. et al. Cardiac-specific Conversion factors to Estimate Radiation Effective Dose from dose-length product in computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 11 (1), 64–74 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2022YFS0075), the Sichuan Provincial Cadre Health Research Project (No. 2020 − 225).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. LS, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Resources; BL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software. XC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis. AM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HP and GZ: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HH: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author XC was employed by company Siemens Healthineers. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, W., Shang, L., Long, B. et al. Impact of physiological and coronary artery disease risk factors on myocardial perfusion in stress computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging. Sci Rep 15, 4967 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88836-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88836-1