Abstract

Electroosmotic drainage has been proposed as a method for reducing moisture content and simultaneously increasing shear strength, thereby enhancing the stability of soft clays. Understanding electroosmotic consolidated soil behavior under wet-dry cycles is vital for assessing long-term stability and performance in a changing environment. In this investigation, electroosmosis-treated soft clay specimens were prepared and subjected to different wetting-drying cycles. The experimental results emphasized that in the case of soft clay which has been treated under identical electroosmosis conditions and subsequently subjected to varying numbers of wetting-drying cycles, it was determined that with an increment in the number of wetting-drying cycles, the crack ratio exhibits an increasing trend. However, the extent of the crack ratio exerts a minimal and almost negligible effect on the average moisture content of the soil mass. Specifically, five wetting-drying cycles can induce a pronounced reduction in the coefficient of variation (COV) of the soil moisture content distribution. Moreover, it was observed that a relatively smaller crack ratio is associated with a relatively greater average shear strength. Simultaneously, the corresponding COV will be larger. Conversely, a larger crack ratio gives rise to a smaller average shear strength, and the corresponding COV will be smaller.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events caused by climate change, clay soil in many regions is subject to alternating wet and dry conditions, which affects the stability and bearing capacity of soil masses as well as the occurrence risks of geological disasters and foundation instability1. In the UK, approximately one in five buildings are at risk of drought because they are built on clays, whose engineering properties are very sensitive to water content change2. Similar climate-related disasters occur every year in France, the USA, China, Canada, and other countries. There have been reports indicating that rainwater infiltration can lead to the collapse of soil masses3, and the drying and wetting process might contribute to the variations of pore-size distribution4,5. The influence of weather conditions on the stability of clay soil foundations has attracted the attention of many geotechnical engineers.

Soft clays, which have high water content, large pore ratio, low shear strength, high compression coefficient and low permeability coefficient, are the most commonly encountered foundations in engineering construction requiring soil treatment6,7,8. Electroosmosis is a process in which, under the influence of an applied direct current electric field, the pore water within the soil mass migrates towards the cathode along with the hydrated cations9. This method was first demonstrated and used successfully as a dewatering tool in Germany by Casagrande in 1936, and since then, the method has been successfully employed in many applications such as soft soil treatment, slope stability, tunneling slurry waste, sports turf, and so forth10,11,12,13,14. Electroosmosis has been proven to be an efficient and rapid drainage consolidation method, which is especially suitable for treating soft clays with high water content and low permeability15.

The shear strength of the soft clay treated by electro-osmosis is significantly enhanced. However, due to the unidirectionality of the direct current electric field, there exists the problem of uneven distribution of shear strength16,17,18,19. If the soft clay, after being electroosmosis strengthened, is subjected to the infiltration of dew, rain, or flood, as well as the evaporation and drying effects of sunlight and wind, which is similar to being in wetting-drying cycles, a deeper understanding of the reinforcement characteristics of the electro-osmosis method can be achieved by studying how the shear strength characteristics will change20,21,22,23. Currently, the majority of relevant studies have centered on the physical, mechanical, cracking, and volume change characteristics of expansive soils, loess, and red soils during wetting-drying cycles24,25,26,27,28. The lack of reports on how wetting-drying cycles affect the shear strength behavior of electroosmotically treated soft clay is unfavorable for evaluating the safety of relevant projects applying this technology.

In this paper, a series of wetting-drying tests were conducted on soft clay treated by electroosmosis to explore the impact of the number of wetting-drying cycles on crack development, water content, and shear strength distribution. The mechanism of shear strength deterioration of electroosmosis-treated soft clay experienced wetting-drying cycles was revealed. Through the investigation of the effect of wetting-drying cycles on the electro-osmotically stabilized soft clay, a more profound comprehension can be achieved regarding the influence of subsequent environmental factors on the macroscopic mechanical performance of the soil mass.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

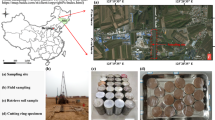

An overview of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1. The internal dimensions of the acrylic model box are 410 mm × 260 mm × 180 mm. The experimental setup for the electroosmotic stage is shown in Fig. 1a. Tubular electrokinetic geosynthetics (EKGs) were chosen as the electrodes, which are made of polyethylene, carbon black, and graphite with good conductivity and corrosion resistance. The details of tubular EKGs have been illustrated in Sun et al.29. Each experiment had four symmetrically distributed anodes (numbered 1–4) and one cathode. The surface of the cathode EKG was wrapped with a filter cloth to prevent soil particles from being carried out when water was drained from the cathode tube. The direct-current (DC) RXN-605D power supply (Zhaoxin, Shenzhen, CHN) has a digital display feature and a steady output voltage with a maximum output power of 60 V × 5 A. Applying a DC current in the field is viable. Despite the presence of several practical aspects and difficulties, like guaranteeing correct electrode installation, sustaining a stable power supply, handling potential electrochemical reactions, and accounting for soil heterogeneity, many successful field applications of electro-osmosis using DC current have been documented. These applications have attested to its efficacy in hastening the consolidation process of soft clayey soils. Nevertheless, meticulous engineering design and site-specific appraisals are essential to maximize performance and resolve any prospective problems that might occur during the field application of DC current.

For water drainage at the cathode, one end of a transparent polyurethane tube was inserted into the bottom of the cathode tube, and the other end was connected to an Erlenmeyer flask and a water-circulating multi-purpose SHB-IIIA vacuum pump (Beijing, CHN). The vacuum pump worked intermittently for 30 s every time. The water was pumped out from the soil specimens and collected in an Erlenmeyer flask with 1000 mL volume. It was then poured into a measuring cylinder with a minimum scale of 1 mL to measure the volume. The power, maximum vacuum degree, and single tap air sucking amount of the vacuum pump are 180 W, 0.085 MPa, and 10 L/min, respectively (Fig. 1a).

The experiment simulated the wetting effect using a rainfall simulation device, which consisted of a humidification system, four wide-angle sprinkler nozzles, and a bracket (Fig. 1b). The power and working pressure of the B50 humidification system (MIUS, Guangdong, CHN) are 25 W and 0.4–0.8 MPa, respectively30. The power of 25 W for the humidification system was determined based on a comprehensive assessment of the required humidification rate and the efficiency of the humidification mechanism. After conducting a series of preliminary tests, it was determined that a power input of 25 W was adequate to attain the intended level of humidity increase within the target environment. The working pressure range of 0.4–0.8 MPa was selected considering the characteristics of the humidification system components, such as the spray nozzles. The lower limit of 0.4 MPa was set to ensure proper atomization and dispersion of the water droplets, allowing for an even distribution of moisture in the air. The upper limit of 0.8 MPa was determined based on the pressure tolerance of the tubing, fittings, and other components in the system. It was connected to the inlet and outlet pipes. One end of the inlet pipe was placed into a beaker containing 500 mL of water, and the other end of the outlet pipe was linked to the sprinkler nozzles. The spacing of the wide-angle sprinkler nozzles along the length direction was 30 cm and along the width direction was 15 cm. The diameter of the wide-angle sprinkler nozzles is 0.25 mm, and the spray flow rate is 120–160 mL/min (Fig. 1b). In the preliminary experiment, the calibrations of the flow rate, droplet size and distribution, as well as the spray angle of the sprinkler nozzles were all carried out.

Drying under natural conditions is simulated by increasing temperature. The blast drying DHG-9145AE oven (Jiecheng, Shanghai, CHN) has an input power of 2 kW, an inner size of 450 mm×550 mm×600 mm, and a temperature control range of 10–300 ℃.

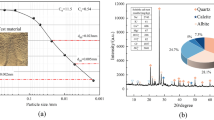

Soil samples

The soil samples used in this study were prepared by artificially mixing clay powder with specified amounts of distilled water. The distilled water, produced by a deionized water DBW-SYS equipment (Dongbo, Shenzhen, CHN), had a pH range of 5.8-6.0 and electrical conductivity less than 6 µS/cm. The clay powder was obtained from a mining company in Jiangning District, Nanjing, China. To obtain the basic geotechnical parameters of the soil powder, common geotechnical tests were performed based on the canonical standard ASTM, as shown in Table 1. The natural water content and plasticity index of the clay powder were 4.2% and 22, respectively. Sieving and hydrometer methods were used to analyze the soil particle size. The percentages of particle grain sizes less than 0.075 mm and 0.005 mm were 79% and 34%, respectively. According to ASTM D2487-06 classification, the soil samples are classified as clay of low plasticity, as indicated by CL. The calculated weight of the distilled water was determined on the basis of the natural water content and weight of the clay powder. The clay powder and distilled water were stirred uniformly to obtain soil samples with the specified water content.

The moisture content of soil is one of the physical property indicators of soil. The level of the moisture content in soil is closely related to the strength and compressibility of cohesive soil. In this experiment, the oven-drying method was adopted to determine the soil water content. Specifically, a soil sample was first weighed and then dried in an oven at 105 degrees Celsius for approximately 10 h. The ratio of the mass of water lost to the mass of the dried soil is defined as the water content. The pH of the soil was also tested before and after electroosmosis treatment. 10 g of the air-dried sample that had passed through a 2-mm sieve was taken and put into a 100-mL wide-mouth bottle. After that, 50 milliliters of pure water free of carbon dioxide was added (while keeping the ratio of soil to water at 1:5). It was shaken on a shaker for 3 min and then left undisturbed for 30 min. Subsequently, the supernatant from the upper part was taken and measured by using precision pH test paper (SSS, Shanghai, CHN). The initial pH value of the soil mass was 6.5 (Table 1).

For each test, 12 kg of clay soil powder with 4.2% water content was measured and mixed with 4.7 kg of distilled water using a mechanical mixer, in order to reach a water content of 45%. The target water content of 45% for soil samples was selected based on the in-situ moisture conditions of the clay soils in China, which ranged from 35–50%14. To remove air bubbles, the soil sample was slowly layered and gently pressed in the model box. The height of the soil sample in each test before treatment was approximately 120 mm. The shear strength of soft clay was directly determined through vane shear tests, which were carried out using a dynamoelectric TT-LVS vane shear device (Zhejiang Geotechnical Instrument, Zhejiang, CHN). The shear strength obtained from this test is equivalent to the undrained strength. The vane shear apparatus has blades that are 25.4 mm in diameter, 25.4 mm in height, and 0.01 mm in thickness. Electrically rotate the drill rod at a rate of 1° per 10 s, and take the peak value or the stable value as the reading when the undisturbed soil undergoes shear failure.The values of the shear stress and rotation angle were automatically recorded. The initial shear strength of the artificially prepared soil was approximately 4 kPa.

Test schemes

The detailed test conditions are presented in Table 2. Six tests (E1-E6) were carried out to explore the influence of wetting-drying cycles on the shear strength behavior of electroosmosis-treated soft clay. E1 only experienced the electroosmotic treatment stage and was used as the control test. The other tests experienced two stages, electroosmosis and wetting-drying cycles on the electroosmosis-treated soil.

During the electroosmotic stage, parallel circuits are used for E1 and E5, E2 and E4, and E3 and E6, respectively. Therefore, the two tests in the parallel circuit have the same electrification and intermittent times. Unless unexpected situations occur (such as laboratory power outages), each experiment usually adopts a working mode of daytime power on and nighttime power off. The voltage was increased from 10 to 50 V in increments of 10 V. Compared to constant-voltage, increased voltage not only helps in effectively delaying the decrease in the trend in the current and improving the consolidation effect but also reduces power consumption and electrode corrosion31,32,33. Selecting a 10 V increment for voltage adjustments is based on a balance of precision, convenience, and practicality. If the drainage rate falls below 2 mL/h, the voltage is further increased by 10 V until the tests are stopped. The total electrokinetic treatment time, including electrification time and intermittent time, for E1 and E5, E2 and E4, and E3 and E6 was 394, 282, and 338 h, respectively (Table 2).

After electroosmosis treatment, E2 and E3, E4 and E5, and E6 experienced 1, 3, and 5 wetting-drying cycles, respectively. Many researchers, such as Khan et al.34 and Estabragh et al.35, have also reported on the behavior of soils subjected to 1, 3, and 5 wet-dry cycles. It was observed that there were no differences in the test results after five cycles of wetting–drying36,37. The dry and wet in the cycles of the present study were not absolute dry and wet, but the stimulation of the humidification and dehumidification process of electroosmosis treated clay. In each cycle, 500 mL of water was evenly sprayed onto the soil surface using the sprinkler nozzles, with a flow rate of 120 mL per minute. Similar to the study by Sun et al.30, different wetting amplitudes can be achieved by controlling the duration of nozzle filling. In this paper, only one scenario was selected for analysis. After simulating rainfall, the soil sample was sealed and left undisturbed for 24 h to allow for better water infiltration into the soil. Subsequently, the model box was placed in a blast drying oven at 35 °C for 21 h to ensure that the weight after drying matched the weight of the soil before spraying, following the methods of Md et al.38, Xu et al.39, and Wang et al.40. The model boxes were weighed before drying and periodically during the drying process to monitor the extent of drying. Although this differs from the natural drying process, it ensures a moderate rate of water evaporation, minimizing the risk of altering the soil’s chemical composition during drying. The soil samples were considered to have completed one wet-dry cycle when the weight loss in the oven was approximately equal to the amount of water added.

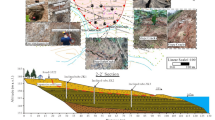

During the electroosmotic stage, the variation of current and discharged water in each test were monitored. After wet-dry stages, the water content and shear strength at different points, with depths of 10, 60, and 100 mm from the soil sample surface, were measured. The layout of these testing points is shown in Fig. 2. A crack image processing software (PCAS) was used for the quantitative measurement of the development of cracks in each test after electroosmosis treatment and wetting-drying cycles. In the study, repeatability tests were conducted. The E2 and E4 experiments were repeated two times under the same experimental conditions. The results demonstrated that the measured values of the main parameters, including crack ratios, water content, and shear strength, had a relatively small standard deviation, which indicates a good repeatability of the test results.

Experimental results and discussion

Electric current variation during electroosmotic consolidation

The electric currents of the three parallel circuits were directly obtained from the DC power supply, as shown in Fig. 3. The applied voltage was increased by 10 V When the drainage rate was lower than 2 mL/h at the current voltage. However, the time of each parallel circuit, when the drainage rate starts to fall below 2 mL/h, was not the same. Hence, the voltage adjustment time of each parallel circuit was not consistent. The electric current in each parallel circuit remained relatively stable at approximately 0.1 A under a voltage of 10 V. Since then, every 10 V increase in the applied voltage in each parallel circuit causes a sudden increase in the electric current and an increase in the amplitude of the current variation. When the voltage reaches 20 V and above, after each intermittent time, the electric current first shows an upward trend and then tends to stabilize or decrease. Intermittent current has several advantages, such as lightening electrode erosion, enhancing electroosmotic flow, and saving power consumption41,42,43. At voltages of 30 V and 40 V, the currents in each experiment were relatively similar. At a voltage of 50 V, the currents of tests E2 and E4, as well as E3 and E6, were both lower than those of E1 and E5 (Fig. 3).

Due to the influence of drainage rate, the parallel connection of E1 and E5 has the longest electrification time under a voltage of 10 V voltage; thus, the subsequent voltage upturn time was later than that of the other two parallel circuits. Moreover, their total electroosmotic treatment time (including intermittent time and electrification time) was the longest. The voltage upturn time of the E2 and E4 parallel circuits is earlier than that of the other two parallel circuits, and the total electroosmotic treatment time (including intermittent time and electrification time) is the shortest. Under the same level of voltage, the potential difference between the anode and cathode will undoubtedly decrease as time passes, which will consequently lead to a reduction in the electric current. This is caused by the drainage of water in the soil, the formation of cracks, as well as the increase in the interfacial resistance between the electrode and the soil44.

Electroosmotic flow during electroosmotic consolidation

The water discharge curve for each test during the electroosmotic stage is illustrated in Fig. 4. The total water discharge volumes of E1-E6 were 904, 910, 606, 979, 897, and 564 mL, respectively. Due to the differences in the intermittent time, power-on duration, voltage adjustment time, and crack propagation degree of each experiment, the drainage rate of each test was not the same at each applied voltage level. The total drainage volumes of the two tests within each parallel circuit (E1 and E5, E2 and E4, E3 and E6) were relatively close. Moreover, all the tests showed that the electroosmotic drainage rate was relatively fast in the early stage, while it decreased significantly in the middle and later stages. The zeta potential is one of the important electrokinetic properties of clay minerals. It is defined as the electrical potential developed at the solid-liquid interface in response to the relative movement of soil particles and water45. The cathode drainage is proportional to the zeta potential and is given by Eqs. (1) and (2).

where \(\:{k}_{e}\) is electroosmotic permeability coefficient, \(\:\nabla\:(-E)\) is the electrical gradient, \(\:\eta\:\) is the dynamic viscosity of the pore fluid, \(\:\epsilon\:\) is the permittivity of the medium, \(\:\zeta\:\) is the zeta potential, \(\:n\) is soil porosity. Under the action of an electric field, hydrogen ions are generated at the anode due to the electrolysis reaction of water, and the pore aqueous solution gradually becomes acidic13. After the electro-osmosis (E1), the pH of the soil in the area near the anode was measured to be between 5.0 and 5.5, the pH of the soil near the cathode remained basically at 6.5, and the pH of the soil in the intermediate area was between 5.8 and 6.2. Acidification causes the value of the soil zeta potential to decrease over time. As a consequence, it further leads to the reduction of the electroosmotic flow velocity in the middle and later stages of the experiment46. As shown in Fig. 5, the electrodes exhibited almost no corrosion. A white precipitate was found covering the surface of the cathode, which should be calcium carbonate precipitate.

For each test, the total electrification time under an applied voltage of 10 V was the longest. Moreover, their water discharge volumes exhibited significant differences, which determined the final relation of the total water discharge volume of each test. Under an applied voltage of 10 V, the difference in the water discharge volume of each test was mainly caused by intermittent current. For example, the first intermittent time of E2 and E4 was 12.7 h and then continuous electrified for 12 h, while the first intermittent time of other tests was 16–17 h and then continuous electrified for 5–7 h, as shown in Fig. 4. Obviously, the first intermittent time of E2 and E4 was shorter than that of the other tests, whereas their subsequent continuous electrification time was the longest. Therefore, the water discharge volumes of E2 and E4 during this period exceeded those of the other tests (Fig. 4).

Similarly, after three identical intervals and electrification experiences, the continuous electrification time of E1 and E5 was approximately 11 h, while that of E3 and E6 was approximately 9 h. Consequently, the water discharge volumes of E1 and E5 started to exceed those of E3 and E6 during this period. Under a low applied voltage of 10 V, the electric current of each test was close and stable. Moreover, intermittent electrification did not cause a larger fluctuation of electric current. According to the aforementioned test phenomenon, it can be concluded that the intermittent time should be shortened and the continuous electrification time should be extended under low applied voltage to promote soil water discharge. Water moving downward during the on-time will move in the opposite direction during the off-time41,47. The optimal intermittent time that generates the maximum electroosmotic flow in the soil is a function of the soil-water-electrolyte system and mainly depends on the time for the double layer to align with the applied electric field43.

Despite E3 and E6 having identical intermittent and electrification times, the drainage rate of E6 was significantly lower than that of E3 during 100–152 h. This may be because the electric current of E6 in the parallel circuit is lower than that of E3. Under low voltage and low current conditions, when the soil moisture content is high, the difference in water discharge is not obvious, and when the soil moisture content becomes low, the difference is obvious. However, after a prolonged intermittent period of 152–186 h, it was difficult for E3 to continue discharge even with an increased voltage. The drainage rate of E6 was increased under an applied voltage of 20 V (Fig. 4). This was because at this moment the soil moisture content of E6 was relatively higher, and raising the voltage increased the electric current in this circuit. It can be concluded that the influence of intermittent electrification on the soil drainage rate is also related to the magnitude of the electric current and the soil moisture content.

Cracks in electroosmosis-treated soft clay experienced wetting-drying cycles

During the process of electroosmotic reinforcement, cracks in the soil developed gradually. Figure 6 depicts the evolution of cracks in the soils upon the completion of electroosmotic consolidation and at the conclusion of each wetting and drying cycle in each test. At the end of electro-osmotic consolidation, the crack development in each test exhibited similarity. A few tiny cracks developed in the soil near the anodes, whereas relatively wide, long, and deep cracks were generated near the cathode along the soil width direction. The occurrence of cracks in the soil adjacent to the anode is primarily attributed to electrolytic water reaction, temperature variations, and drainage. In contrast, the cracks near the cathode are mainly induced by the electrolytic water reaction. The production of gases from electrolyzed water can cause significant changes in the stress state and the physical structure of the soil, resulting in the development of cracks, which in turn leads to an increase in the resistance of the circuit13,48. The development of cracks leads to a reduction in the contact area of the electrodes and soil, which reduces the electroosmotic drainage effect.

The process of wetting-drying cycles affects the distribution of soil water content, resulting in shrinkage deformation and cracking of the clay soil, destroying the integrity of the soil and deteriorating its mechanical properties. After one wetting-drying cycle, tinier cracks developed around the anodes and two obvious transverse cracks developed around the cathode. When the tensile stress produced by the moisture gradient is greater than the tensile strength of the soil, cracks begin to form49. After three wetting-drying cycles, the cracks on the soil surface had become significantly pronounced.More scattered cracks were emitted from the anodes and cathode, and annular cracks around the anodes. The cracks propagate along the original healing crack, and the new crack surface becomes a new surface. The water content gradient at the interface gets re-distributed, thus the cracks expand around49. With the development of cracks, the smoothness of the edges decreases gradually, resulting in a rougher shape. After five wetting-drying cycles, the width of the emitter cracks around the cathode increased, the surface soil near the anode was broken, and more tiny cracks developed on the soil surface (Fig. 6). The cracks divides the specimen into many small blocks, the rate of water loss becomes faster, soil water content easily acquires equilibrium, and appear the larger the water content gradient is more difficult, so the crack tends to get stabilized49.

The Pore and Crack Analysis System (PCAS) was used for the quantitative measurement of crack development in each test by processing the crack images. Binarization images and crack parameters were then obtained. The crack ratio was determined by calculating the ratio of the crack area to the total area of the soil sample49. Table 3 illustrates that the crack ratios of the soil samples after electroosmosis treatment in E1-E6 are 4.7, 3.7, 3.8, 4.0, 4.2, and 5.0%, respectively. The crack ratios of the electroosmosis-treated soil after different wetting-drying cycles in E2-E6 are 6.6, 7.3, 11.3, 14.9, and 16.6%, respectively.

The crack ratios of electroosmosis-treated soils in the six tests vary from 3.7 to 5.0% (Table 3). Throughout all the experiments, it was demonstrated that cracks became more pronounced as the number of wetting-drying cycles increased. Tang et al.50 pointed out that the impact of wetting-drying cycles on soil desiccation cracking behavior is not limitless and is associated with soil properties and initial state.

Water content of electroosmotic-treated soft clay experienced wetting-drying cycles

After conducting the shear strength test, measure the moisture content of the soil at the designated points, as shown in Fig. 2. The average moisture content and the coefficient of variation (COV) for all measurement points in each test are summarized in Table 4. Due to unforeseen circumstances, E2 obtained only a few data, so its COV is not listed. The average moisture content for each test after being subjected to different wetting-drying cycles is approximately 30%. The moisture content of each test was affected not only by the wetting-drying cycles but also by water reduction (including water discharge, evaporation, electrolytic water consumption, and so forth) in the soil during the electroosmotic stage51. It is known from the aforementioned results that the water discharge volumes of the E3 and E6 electroosmotic stages are much lower than those of the other four tests with close water discharge. It is preliminarily concluded that the average moisture content of the soil after electroosmotic strengthening in E3 and E6 should be higher than that of the other four tests. However, the moisture content of E3 and E6, after experiencing one and five wetting-drying cycles, respectively, is not much different from that of the other four tests. This may be due to the difference in evaporation rates of soil with varying moisture contents at the same temperature and time; higher moisture content leads to greater evaporation52.

The water content of the measuring points at the same horizontal distance from anode 1 and anode 2 was averaged, and the distribution of the water content of each test was obtained, as shown in Fig. 7. The moisture content of each test ranges from 25 to 35%. The soil moisture content of S1-S3 section shows an increasing trend, while that of S6-S4 section is not symmetrical with it. Especially for E3, the soil moisture content of S6-S4 section is significantly higher than that of S1-S3 section. This may be due to the poor drainage of the soil in the S4-S6 section of E3 during the electroosmotic stage. The moisture content of the soil reinforced by electroosmosis always increased continuously from the anode to the cathode16. For E3, E4, and E6, the water content in the S6 section is higher than that in the S5 section, which indicates that the water content of the three tests in the S6 section must be affected by the wetting-drying cycles.

The water discharge volumes and electrokinetic treatment durations of E1 and E5 were comparable during the electroosmotic stage. After the soil in E5 underwent three wetting-drying cycles, the water content in sections S2 and S3 decreased by approximately 4% compared to E1, while the water content in other sections remained nearly the same (Fig. 7). During the electroosmotic stage, the electrokinetic treatment times for E3 and E6 were identical, but the water discharge volume of E6 was 42 mL less than that of E3. However, after the soil in E6 underwent five wetting-drying cycles post-electroosmosis, the moisture content in sections S1 and S2 was slightly higher compared to E3, while the moisture content in sections S4-S6 decreased by about 4%, resulting in a more uniform moisture distribution.

Shear strength of electroosmotic-treated soft clay experienced wetting-drying cycles

After each test, the soil vane shear strength was tested according to the measurement point layout, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The average shear strength and COV of all measurement points in each test are shown in Table 5. Due to unforeseen circumstances, E2 obtained only a few data, so its coefficient of variation is not listed. The shear strength of the measuring points at the same horizontal distance from anode 1 and anode 2 was averaged, and the distribution of the shear strength of each test was obtained, as shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Table 5, there were notable differences in both the average shear strength and the COV among the tests. The highest average shear strength and COV were observed for E3 (one wetting-drying cycle). The average shear strength for E1 (no wetting-drying cycle) and E4 (three wetting-drying cycles) were similar. The average shear strength of E2 (one wetting-drying cycle), E5 (three wetting-drying cycles), and E6 (five wetting-drying cycles) were also similar, with E6 exhibiting the lowest COV for shear strength. The shear strength distribution for E6 was relatively uniform, whereas the other tests exhibited a decreasing trend from the anode to the cathode (Fig. 8). The data presented in Table 5; Fig. 8 do not seem to reveal any discernible pattern. This is because the shear strength in each test is influenced not only by the wetting-drying cycles but also by soil drainage consolidation and physicochemical reactions during the electroosmotic stage. Additionally, there are known differences in drainage during the electroosmotic stage across the tests (Fig. 4).

For E1 and E5, the water discharge volumes, electrification time, average moisture content, and moisture content distribution are relatively similar. However, E5 exhibits lower average shear strength and COV compared to E1. This reduction is attributed to the decreased shear strength of the soil near the anodes (S1 and S6 sections) in E5. The results indicate that after three wetting-drying cycles, the shear strength of the soil near the anodes decreased, leading to a corresponding reduction in both the average shear strength and COV. In the electroosmotic stage, the water discharge volume and total electroosmotic treatment time for E3 were lower than those for E1 but were similar to those for E6. However, after the wetting-drying cycles, E3 exhibited higher average shear strength and COV compared to E1, while E6 showed lower values than E1. This discrepancy is due to the uneven distribution of shear strength in the electroosmosis-treated soil in E3, where the shear strength between electrodes 1 and 2 and the cathode is significantly higher than that between electrodes 3 and 4 and the cathode. The soil shear strength at sections S1 and S6 near the anode is lower for E6 compared to E1. These results indicate that while the average shear strength and COV of the soil treated with electroosmosis are minimally affected by a single wetting-drying cycle, they decrease significantly after five cycles. Despite both E4 and E5 undergoing three wetting-drying cycles after electroosmosis treatment, E4 exhibited a higher average shear strength than E5. This is attributed to the higher shear strength observed at sections S1 and S6 near the anode in E4 compared to E5, with minimal differences at other points. The increased water discharge in E4 during the electroosmotic stage likely contributed to this disparity. Therefore, it is inferred that the electroosmosis-treated soil in E4 had a higher shear strength before the wetting-drying cycles compared to E5.

Discussion

The permeability of clay soil is 5.7 × 10^-7 cm/s, as shown in Table 1. Based on the permeability coefficient, the theoretical infiltration depth of water into the soil over a 24-hour period is calculated to be 0.5 mm. However, due to factors such as the development of surface cracks in the soil, separation between the electrodes and the soil, and the detachment of the shrinking soil boundary from the model box, the actual water infiltration is expected to exceed the theoretical estimate. Similar to the study by Sun et al.30, different wetting amplitudes can be achieved by controlling the duration of nozzle filling. In the experimental design phase, the spray flow rate was initially considered in relation to various rainfall intensities, including light, moderate, and heavy rain. However, after reviewing the testing methods for rainfall, it became clear that direct comparisons were not feasible. Consequently, the experiment focused on selecting the minimum spray flow rate from the spraying system, which remains representative of one of the rainfall scenarios. Future research will continue to explore the wetting effect of electro-osmotic soil reinforcement under varying rainfall intensities through simulation.

Based on the experimental design outlined in this paper, a series of wetting-drying tests were conducted on electroosmosis-treated soft clay to investigate the effects of wetting-drying cycle durations on crack development, water content, and shear strength characteristics of the electroosmosis-reinforced soft clay. When electroosmosis-treated soft clay underwent wetting-drying cycles, the COV of soil moisture content decreased, particularly after five cycles, where the COV dropped to 3.5%. This indicates that the wetting-drying cycles, especially after five cycles, help achieve a more uniform distribution of moisture content in the electroosmosis-treated soil, while the average moisture content remains relatively stable.

Additionally, after three or five wetting-drying cycles, the shear strength of the soil near the anode decreases significantly, resulting in a reduction in both the average shear strength and the COV. In contrast, a single wetting-drying cycle has a minimal impact on the shear strength of soil treated by electroosmosis. This is attributed to the formation of substantial aggregates in the soil near the anode due to drainage consolidation and chemical cementation during the electroosmotic stage. There are fissures present between the large aggregates. When water seeps into these cracks, it disrupts the chemical cementation holding the soil particles together. As a result, after several wetting-drying cycles, the shear strength of the soil near the anode will significantly decrease53. In addition, the impact of three wetting-drying cycles on the average shear strength of the soil is more pronounced than that of five cycles. The COV of the shear strength for electroosmosis-treated soil subjected to five wetting-drying cycles is the smallest and shows a more uniform distribution.

It should be noted that the presented results are derived from the experimental data obtained in Jiangning District, Nanjing, China. Since the data is location-specific, further calibration might be necessary when applying these proposed results to other zones to ensure their accuracy and reliability. Furthermore, the soil collapse and variations of pore-size distribution during drying and wetting process, as well as the soil-water characteristic curve, are not considered in this study. Further research is required to conduct a comprehensive analysis of these aspects and their potential influences on the overall performance of the electroosmotically treated soft clay.

In practical engineering applications, soft clay treated by electro-osmosis should be protected from prolonged exposure to external environmental conditions, such as rainfall and evaporation, which can induce wet-dry cycling. Surface cracks in the soil should be promptly repaired and reinforced to prevent water from infiltrating through these cracks and accelerating the deterioration of the soil. After the soft clay undergoes electro-osmotic treatment and is subjected to wet-dry cycles, its shear strength must be reassessed. Moreover, further research on optimizing electro-osmosis design is necessary to better resist the effects of natural wet-dry cycling.

In general, the soft clay treated under the same electroosmosis conditions and then subjected to different numbers of wetting-drying cycles shows that the smaller the crack ratio is, the greater the average shear strength will be, but the corresponding COV will also be larger. Conversely, the larger the crack ratio is, the smaller the average shear strength will be, and the corresponding COV will also be smaller.

Conclusions

With the experimental results of electroosmosis-treated soft clay experienced different wetting-drying cycles by the six experiments, the important conclusions have summarized as follows.

During the electroosmosis phase, it was observed that reducing the intermittent time and extending the continuous electrification time at low applied voltage helps promote soil water discharge. For the soft clay that has been treated under the same electroosmosis conditions and then subjected to different numbers of wetting-drying cycles, it is found that as the number of wetting-drying cycles increases, the crack ratio becomes larger. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the crack ratio has a negligible influence on the average moisture content of the soil mass. Five wetting-drying cycles can result in a remarkable decrease in the COV of the soil moisture content distribution. In addition, it is noted that a smaller crack ratio corresponds to a greater average shear strength. At the same time, the corresponding COV will be larger. Conversely, a larger crack ratio leads to a smaller average shear strength, and the corresponding COV will be smaller.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Stark, T. D. & Duncan, J. M. Mechanisms of strength loss in stiff clays. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 117(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1991)117:1(139) (1991).

Wang, D. Y., Tang, C. S., Cui, Y. J., Shi, B. & Li, J. Effects of wetting–drying cycles on soil strength profile of a silty clay in micro-penetrometer tests. Eng. Geol. 206, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2016.04.005 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Experimental investigation of the collapsibility of loess subjected to water invasion. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 83(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03532-6 (2024).

Zhai, Q. et al. Prediction of the soil–water characteristic curves for the fine-grained soils with different initial void ratios. Acta Geotech. 18(10), 5359–5368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01833-4 (2023).

Zhai, Q. et al. A new domain model for estimating water distribution in soil pores during the drying and wetting processes. Eng. Geol. 322, 107180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107180 (2023).

Almeida, M. S. S. et al. Ground improvement techniques applied to very soft clays: state of knowledge and recent advances. Soils Rocks. 46, e2023008222. https://doi.org/10.28927/SR.2023.008222 (2023).

Burland, J. B. On the compressibility and shear strength of natural clays. Geotechnique 40, 329–378. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1990.40.3.329 (1990).

Horpibulsuk, S., Yangsukkaseam, N., Chinkulkijniwat, A. & Du, Y. J. Compressibility and permeability of Bangkok clay compared with kaolinite and bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 52, 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2011.02.014 (2011).

Reuss, F. F. Charge-induced flow. Proc. Imp. Soc. Naturalists. Moscow. 3, 327–344 (1809).

Casagrande, I. L. Electro-osmosis in soils. Geotechnique 1, 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1949.1.3.159 (1949).

Lamont-Black, J., Huntley, D., Glendinning, S. & Jones, C. J. F. P. The use of Electrokinetic geosynthetics (EKG) in enhanced performance of sports turf. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Geosynthetics, Yokohama, Japan, September, 18–22 (2006).

Kalumba, D., Glendinning, S., Rogers, C. D. F., Tyrer, M. & Boardman, D. I. Dewatering of tunneling slurry waste using electrokinetic geosynthetics. J. Environ. Eng. 135, 1227–1236. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2009)135:11(1227) (2009).

Martin, L., Alizadeh, V. & Meegoda, J. Electro-osmosis treatment techniques and their effect on dewatering of soils, sediments, and sludge: a review. Soils Found. 59, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2018.12.015 (2019).

Sun, Z. H., Geng, J. X., Wei, G. W. & Li, W. J. Engineering application of vacuum preloading combined with electroosmosis technique in excavation of soft soil on complex terrain. Plos One. 18, e0288026. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288026 (2023).

Estabragh, A. R., Naseh, M. & Javadi, A. A. Improvement of clay soil by electro-osmosis technique. Appl. Clay Sci. 95, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2014.03.019 (2014).

Pandey, B. K. & Rajesh, S. Enhanced engineering characteristics of soils by electro-osmotic treatment: an overview. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 4649–4673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-019-00973-3 (2019).

Tang, X. W., Xue, Z. J., Yang, Q., Li, T. & VanSeveren, M. Water content and shear strength evaluation of marine soil after electro-osmosis experiments. Dry. Technol. 35, 1696–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2016.1270299 (2017).

Hansbo, S. Soil improvement by means of electro-osmosis. 6th international Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering, Arlington, VA, 11–16, August (2008).

Rittirong, A., Douglas, R. S., Shang, J. Q. & Lee, E. C. Electrokinetic improvement of soft clay using electrical vertical drains. Geosynth Int. 15, 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1680/gein.2008.15.5.369 (2008).

Ying, Z., Benahmed, N., Cui, Y. J. & Duc, M. Wetting-drying cycle effect on the compressibility of lime-treated soil accounting for wetting fluid nature and aggregate size. Eng. Geol. 307, 106778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106778 (2022).

Pasculli, A., Sciarra, N., Esposito, L. & Esposito, A. W. Effects of wetting and drying cycles on mechanical properties of pyroclastic soils. Catena 156, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.04.004 (2017).

Diel, J., Vogel, H. J. & Schlüter, S. Impact of wetting and drying cycles on soil structure dynamics. Geoderma 345, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.03.018 (2019).

Tang, C. S. et al. Effects of wetting-drying cycles and desiccation cracks on mechanical behavior of an unsaturated soil. Catena 194, 104721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104721 (2020).

Nowamooz, H. & Masrouri, F. Mechanical behaviour of expansive soils after several drying and wetting cycles. Geomech. Geoengin. 5, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/17486025.2010.521588 (2010).

Estabragh, A. R., Parsaei, B. & Javadi, A. A. Laboratory investigation of the effect of cyclic wetting and drying on the behaviour of an expansive soil. Soils Found. 55, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2015.02.007 (2015).

Rosenbalm, D. & Zapata, C. E. Effect of wetting and drying cycles on the behavior of compacted expansive soils. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 29, 04016191. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001689 (2017).

Wang, C., Zhang, Z. Y., Liu, Y. & Fan, S. M. Geometric and fractal analysis of dynamic cracking patterns subjected to wetting-drying cycles. Soil. Till Res. 170, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2017.02.005 (2017).

Allam, M. M. & Sridharan, A. Effect of wetting and drying on shear strength. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 107, 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1061/AJGEB6.0001117 (1981).

Sun, Z. H. et al. Consolidation of soft clay by cyclic and progressive electroosmosis using electrokinetic geosynthetics. Arab. J. Geosci. 15(13), 1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10380-3 (2022).

Sun, Z. J., Yang, X. Y., Zhao, Z. Y. & Zhang, B. C. Study on deformation characteristics of different angle loess slopes under wet-dry alternation. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10377-y (2022).

Li, X. B. et al. Slurry improvement by vacuum preloading and electro-osmosis. P. I. Civil. Eng-Geotec 172, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.17.00181 (2019).

Liu, F. Y. et al. Improvement of dredger fill by stepped vacuum preloading combined with stepped voltage electro-osmosis. Mar. Georesour Geotec. 39, 822–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2020.1766606 (2021).

Bian, X. Y., Yang, H. D., Liu, H., Xu, Z. Y. & Zhang, R. J. Experimental study on the improvement of sludge by vacuum preloading-stepped electroosmosis method with prefabricated horizontal drain. Geotext. Geomembranes. 52, 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geotexmem.2024.04.001 (2024).

Khan, M. A., Hossain, M. S., Khan, M. S., Samir, S. & Aramoon, A. Impact of wet-dry cycles on the shear strength of high plastic clay based on direct shear testing. In Geotechnical Frontiers 2017, 615–622 (2017).

Estabragh, A. R., Moghadas, M. & Javadi, A. A. Effect of different types of wetting fluids on the behaviour of expansive soil during wetting and drying. Soils Found. 53, 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2013.08.001 (2013).

Rao, S. M., Reddy, B. V. V. & Muttharam, M. The impact of cyclic wetting and drying on the swelling behaviour of stabilized expansive soils. Eng. geol. 60, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7952(00)00103-4 (2001).

Kalkan, E. Impact of wetting–drying cycles on swelling behavior of clayey soils modified by silica fume. Appl. Clay Sci. 52, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2011.03.014 (2011).

Md, S. H., Ling-Wei, K. & Song, Y. Effect of Drying-Wetting Cycles on Saturated Shear Strength of Undisturbed Residual Soils. Am. J. Civ. Eng. 4(4), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajce.20160404.15 (2016).

Xu, J., Li, Y. F., Wang, S. H., Wang, Q. Z. & Ding, J. L. Shear strength and mesoscopic character of undisturbed loess with sodium sulfate after dry-wet cycling. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 1523–1541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01646-4 (2020).

Wang, J. J., Zhou, Y. F., Wu, X. & Zhang, H. P. Effects of soaking and cyclic wet-dry actions on shear strength of an artificially mixed sand. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 23, 1617–1625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0896-2 (2019).

Tao, Y. L., Zhou, J., Gong, X. N., Chen, Z. & Hu, P. C. Influence of polarity reversal and current intermittence on electroosmosis. Ground Improv. Geosynthetics. 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413401.020 (2014).

Micic, S., Shang, J. Q., Lo, K. Y., Lee, Y. N. & Lee, S. W. Electrokinetic strengthening of a marine sediment using intermittent current. Can. Geotech. J. 38, 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-098 (2001).

Mohamedelhassan, E. & Shang, J. Q. Effects of electrode materials and current intermittence in electroosmosis. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng-Gr. 5, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1680/grim.2001.5.1.3 (2001).

Sun, Z. H., Zhang, C., Demarscho Eugene, B. & He, X. W. Electroosmotic flow in soft clay and measures to promote movement under direct current electric field. Plos One. 19(4), e0302150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302150 (2024).

Liu, Y. N., Zhuang, Y. F., Xiao, F. & Liu, Z. T. Mechanism for reverse electroosmotic flow and its impact on electrokinetic remediation of lead-contaminated kaolin. Acta Geotech. 18(3), 1515–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-022-01640-3 (2023).

Azzam, R. & Oey, W. The utilization of Electrokinetics in Geotechnical and Environmental Engineering. Transp. Porous Med. 42, 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006753622691 (2001).

Gopalakrishnan, S., Mujumdar, A. S. & Weber, M. E. Optimal off-time in interrupted electroosmotic dewatering. Separations. Technol. 6, 197–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-9618(96)00153-1 (1996).

Sun, Z. H., Xu, S. W., Zhang, C., Geng, J. X. & Gu, Y. Electroosmotic strengthening of soft clay under different electrification modes. Energy Sci. Eng. 12(7), 3126–3141. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1806 (2024).

Huang, Z., Wei, B. X., Zhang, L. J., Chen, W. & Peng, Z. M. Surface crack development rules and shear strength of compacted expansive soil due to dry–wet cycles. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 2647–2657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-018-00784-y (2019).

Tang, C. S., Shi, B., Liu, C., Zhao, L. Z. & Wang, B. J. Influencing factors of geometrical structure of surface shrinkage cracks in clayey soils. Eng. Geol. 101, 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2008.05.005 (2008).

Mahalleh, H. A. M., Siavoshnia, M. & Yazdi, M. Effects of electro-osmosis on the properties of high plasticity clay soil: chemical and geotechnical investigations. Electroanal. Chem. 880, 114890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.114890 (2021).

Hanks, R. J., Gardner, H. R. & Fairbourn, M. L. Evaporation of water from soils as influenced by drying with wind or radiation. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 31, 593–598. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1967.03615995003100050001x (1967).

Xu, X. T. et al. Effect of wet-dry cycles on shear strength of residual soil. Soils Found. 61, 782–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2021.03.001 (2021).

Funding

This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42207189), Key Laboratory of New Technology for Construction of Cities in Mountain Area (LNTCCMA-20230108), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX24_2072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, and writing–review and editing, Z.S.; writing–original draft, formal analysis, visualization, and validation, Z.S. and C.W.; investigation, Z.S., C.W., Y.Q. and S.L.; resources and methodology, Y.Q.; data curation, C.W., Y.Q. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Z., Wu, C., Qing, Y. et al. Influence of wetting-drying cycles on the shear strength behavior of electroosmotically treated soft clay. Sci Rep 15, 5748 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88868-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88868-7