Abstract

Carbon sequestration and emission reduction in apple cultivation are of great significance for achieving sustainable agricultural development and combating climate change. However, the status of carbon emissions from apple cultivation is unclear, and this study will provide implications for the agriculture sector. This study applied the life cycle assessment method to quantify carbon emissions and analysed the footprint composition of apple orchards in China, and identified the emissions peak based on the Mann–Kendall analysis. The results showed that the carbon emissions of apple cultivation reached the carbon peak in 2014. The carbon emissions per unit area (CEA) and per unit yield (CEY) were 5.79 t CO2eq ha−1 and 0.23 kg CO2eq kg−1 in 2021, respectively. Carbon emissions from fertilizers (54.4%) and irrigation electricity (30.9%) were identified as the dominant components in apple orchards. Specifically, Henan and Shandong exhibited higher growing advantages, characterized by higher carbon economic efficiency and lower CEY. The carbon emissions of the ideal scenario will be decreased 69.6% through optimizing fertilizers and energy restructuring. In conclusion, promoting low-carbon development in apple orchards can be achieved through targeted in-field mitigation measures, such as optimizing the amount and types of fertilizers, and adopting new energy for agricultural machinery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Apple (Malus pumila Mill.) is one of the world’s most widely cultivated fruits1. China holds the distinction of being the largest apple cultivation country, producing 44.07 Mt, which accounts for 55% of the global production in 20212. Apple orchards represent a unique farmland ecosystem with substantial carbon sequestration potential that can offset a portion of carbon emissions3,4. Apple orchards simultaneously serve as both carbon emission sources and carbon sinks. Therefore, understanding the carbon emissions from apple orchards is crucial for advancing greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation and carbon sequestration in the agricultural sector and achieving carbon neutrality goal.

The carbon footprint serves as a common indicator for assessing the environmental impact of GHG emissions5,6,7. A detailed analysis of carbon footprint composition provides a foundation for identifying and selecting appropriate mitigation actions and carbon sequestration measures. Life cycle assessment (LCA) is widely used to evaluate and calculate carbon footprints of products or systems5,8,9,10,11. The agricultural inputs in the process of apple cultivation, such as fertilization, irrigation, pesticides, and agricultural mechanization constitute carbon sources and are likewise an important part of the carbon footprint. These agricultural inputs generate carbon emissions at the upstream producing stage, and field application of fertilizers generates N2O emissions and nitrogen losses, which harm the environment. Previous studies had shown that carbon footprints of different fruit production based on a field survey, including oranges, pears, apples, bananas, and peaches12. Li et al.13 comprehensively compared the carbon footprint of different crops based on field systems in 2018. Chen et al.14 identified the main crops’ carbon footprints in China, and the carbon footprint of different crops was analysed on the time scale, but it didn’t consider the differences between different regions in China. Targeted mitigation opportunities for apple orchards remain unclear due to a lack of comprehensive provincial-level analyses spanning a significant time period. Additionally, there has been limited investigation into the composition and dynamics of carbon emissions across different regions and timeframes. Thus, it is urgent to discuss these matters and consider regional heterogeneity, tailoring effective mitigation strategies for apple cultivation in China.

The carbon peak is an important period and process of achieving carbon neutrality. As part of its commitment, China aims to reach carbon emissions peak by 2030. The attainment of this ambitious national goal requires efforts from individual sectors. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the carbon emissions peak in the agricultural sector to ensure timely achievement of China’s overall carbon peaking goal. However, projecting the peak for the agricultural sector has been challenging due to the complexity of the agricultural system. GHG emissions varied across regions, crop types, and management practices15,16,17,18, resulting in different years of carbon peak. Thus, it is imperative to identify the peaks of carbon emissions at both sub-national and food-specific levels. By analysing the time-scale changes of carbon emissions from apple orchards in each province, we can better assess whether and when carbon emissions have a peak. And this will help to provide a strong theoretical basis for the low-carbon development of apple orchards in the future.

To address these challenges, this study comprehensively investigated the carbon emissions based on the time-series agricultural data-set from 2002 to 2021. This study explored the spatial and temporal dynamics changes of carbon emissions from apple cultivation, analysed the footprint composition leading to changes trend over time. And we also identified the regional differences in the development of apple orchards to analyse the advantages of apple cultivation in different provinces. Our results will show a new perspective to assess whether and when GHG emissions of apple orchards reach their carbon peak. This will provide scientific and technological supports for proposing a low-carbon development model of apple orchards.

Methods

Study area

To quantify the carbon footprint of Chinese apples, this study selected primary apple cultivation provinces and municipalities, including Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, Liaoning and Beijing. The cultivation area and production of apples were shown in Fig. 1, which were used to estimate total carbon emissions. According to the China Rural Statistical Yearbook, these provinces’ apple production reached 40.06 Mt and the planting area reached 1612.8 thousand ha in 2021, accounting for 81.64% and 83.02% of the total national production and planting area, respectively19.

Life cycle assessment and system boundary

The life cycle assessment (LCA) method is divided into “from cradle to grave” and “from cradle to farm gate”, following the requirements and guidelines of the international organization for standardization20. It consists of defining objectives and scope, data collection, impact assessment and life cycle interpretation. In the process of agricultural production, the “from cradle-to-farm gate” LCA method was adopted in this study.

The system boundary, as illustrated in Fig. 2, encompassed upstream agricultural input production and farm cultivation. First, the upstream production of agricultural inputs, such as chemical fertilizers, pesticides, film, irrigation electricity, and agricultural mechanical diesel fuel, generated CO2 emissions. Second, the in-field application of chemical and manure fertilizers emitted direct and indirect N2O emissions. Third, the CH4 emissions or sinks in the field are considered. However, the carbon sequestration of soil and trees was not considered due to the lack of data in different regions orchards. The GHG emissions in apple orchards were CO2, N2O and CH4, and both were expressed in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2eq). The functional units were carbon emissions per unit yield (CEY) (kg CO2eq kg−1) and carbon emissions per unit area (CEA) (t CO2eq ha−1).

Data acquisition

The data on planting area and production from 2002 to 2021 were collected from the China Rural Statistical Yearbooks19. Agricultural inputs and economic data from 2002 to 2021 were acquired from the China Agricultural Products Cost–Benefit Yearbooks21, which were shown in the supplementary data. The dosages of manure, pesticide, and diesel fuel were calculated based on costs and unit prices. The reciprocal of the consumer price index (CPI) is usually regarded as the purchasing power index of money (https://www.stats.gov.cn/), and the inflation/deflation of money was calculated by using CPI data provided by the World Bank Group, and the base year of CPI is 2010 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator). Emission factors were derived from relevant literatures and guidelines (Table 1).

Carbon emissions quantification

In the apple orchard system, all sources of carbon emissions need to be calculated at different stages of apple production.

First, the carbon emissions from the upstream production of agricultural inputs in apple orchards are estimated using the following equation:

where \({E}_{i}\) represents the carbon emissions from agricultural inputs in apple orchards (kg CO2eq ha−1); \(i\) represents different types of agricultural inputs, including chemical fertilizers, pesticide, agricultural film, mechanical fuel, and irrigation electricity; \({I}_{i}\) represents the application amount of different agricultural inputs (kg/kWh/L ha−1); and \({EF}_{i}\) is the emission factor for different agricultural inputs.

Second, the direct and indirect N2O emissions from nitrogen fertilizers application in the field are estimated using the following equation. Direct N2O emissions are directly from fertilizers application, while indirect N2O emissions are from atmosphere N deposition and N leaching/runoff.

where \({E}_{direct}\) represents the direct N2O emissions from fertilizers in-field application (kg CO2eq ha−1); n represents different types of nitrogen fertilizers, and the nitrogen nutrient content of manure is 0.51%29, \({F}_{n}\) represents the input of nitrogen fertilizers (kg N ha−1); 0.01 (kg N2O kg−1 N) represents the emission factor of N2O caused by chemical fertilizers and manure28; \(44/28\) represents the N2O-N conversion coefficient into N2O; 273 represents the 100-year global warming potential (GWP) of N2O3.

where \({E}_{indirect}\) represents the indirect N2O emissions (kg CO2eq ha−1); \({E}_{indirect,d}\) represents the indirect N2O emissions from atmospheric nitrogen deposition (kg CO2eq ha−1);\({E}_{indirect,l}\) represents the indirect N2O emissions from leaching or runoff nitrogen (kg CO2eq ha−1); \({F}_{n}\) represents the input of nitrogen fertilizers (kg N ha−1); 0.11 (kg N2O kg−1 N) represents the proportion of volatile nitrogen; 0.24 (kg N kg−1) represents the proportion of leaching or runoff nitrogen; 0.01 (kg N2O kg−1 N) represents the emission factor of fertilizers applied in the field; and 0.011 (kg N2O kg−1 N) represents the emission factor of leaching or runoff nitrogen28.

Third, the CH4 emissions in the field are estimated using the following equation:

where \({E}_{CH4}\) represents the emissions of CH4 (kg CO2eq ha−1); \(C{E}_{CH4}\) represents the uptake of CH4 in the field (kg CH4 ha−1)30, 27.9 represents the 100-year global warming potential (GWP) of CH43.

Consequently, the carbon emissions per unit area (CEA), carbon emissions per unit area (CEY), and total carbon emission (CE) of apple production are calculated using the following equations:

where \(CEA\) represents the carbon emissions per unit area from the apple orchards (t CO2eq ha−1); A represents the total area of the apple orchards; \(CEY\) represents the carbon emission per unit yield (kg CO2eq kg−1); \(Y\) represents the apple yield per unit area (kg ha−1); CE represents the total carbon emissions from the apple orchards (Mt CO2eq).

Analysis of economic and environmental factors

To better understand the relationship between carbon emissions and economic development, we introduced carbon economic efficiency (CEE) as an indicator to evaluate apple economic development8. Higher CEE indicated a greater planting advantage. CEE was calculated using the following equation:

where \(CEE\) represents carbon economic efficiency (yuan (kg CO2eq)−1); \(NP\) represents the net profit per unit area (yuan ha−1); and \(CEA\) represents the carbon emissions per unit area (kg CO2eq ha−1).

Carbon peak assessment

This study used the Mann–Kendall (MK) trend test method to analyse whether and when the NCE of apple production in China peaked. The MK test is a non-parametric trend test method for time series data. It has low requirements on the original data, as it does not need to meet specific distribution assumptions. This allows the MK trend analysis to overcome restrictions on the form of sequence distribution31.

The principles of carbon peak assessment are as follows: First, the maximum value of carbon emissions is identified in the time series data. If the data volume is greater than 5 years after the maximum value in the region (n > 5), the MK test is conducted for the carbon emission data. If the data volume is less than or equal to 5 years after the maximum value (n ≤ 5), the trend test cannot be conducted, and indicates that the carbon peak has not been achieved. If there is a significant downward trend in carbon emissions in the region after the maximum year, this region is considered to have reached its peak (P < 0.05). If there is no significant trend, it is considered that this region is on the carbon peak plateau (P ≥ 0.05). The MK test method’s specific calculation steps32 are as follows:

where 1 ≤ i, j ≤ n; \(sgn\left({x}_{j}-{x}_{i}\right)\) is the indicator function, depending on whether the plus or minus sign of \({x}_{j}-{x}_{i}\) is 1, 0 or \(-1\). S represents the test statistical variables.

where \(g\) denotes the number of knotted arrays in the original data; \({t}_{i}\) denotes amount of data in the \(i\) knotted array. varS represents variance. Z represents the standardization of statistical variables. If the value of Z is greater than 0, it means that the sequence has an upward trend, if the value of Z is less than 0, it means that the sequence has a downward trend.

Pathways of emissions reduction

In order to investigate the potential for emissions reduction of apples in China, this study developed two carbon emission scenarios for apples in 2030 and 2060. During the cultivation of apples, GHG emissions were primarily attributable to fertilizers and irrigation electricity. It would be beneficial to consider ways to optimize field cultivation management and clean energy (such as solar energy, windy energy etc.) use as a means of reducing future emissions from apple orchards in China. Consequently, the most significant opportunity for emission reductions at the cultivation stage lies in the optimization of the quantity of fertilizers application and the introduction of novel fertilizers. According to the government policy of action plan for fertilizers and pesticide reduction by 2025 (Ref.33, https://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/), the report pointed out that the amount of fertilizers should be reduced and the proportion of new fertilizers type and organic fertilizers should be increased. By 2030, we assumed that fertilizers would be reduce to 80%, as the application of nitrogen fertilizer is expected to decrease by 20% to 28% through optimizing nitrogen fertilizer34. And Liu et al.35 suggested nitrogen fertilizer application has a great potential of 49%, through the integration of comprehensive nutrient management strategies. Therefore, we assumed fertilizers would reduce to 80% in 2030 and 50% in 2060. As the report pointed out the dosage of pesticides should be reduced 10%, we assumed pesticides would reduce to 90% by 2030 and 80% by 2060. The synthesis report 2020 on China’s Carbon Neutrality36 stated that decarbonization will be achieved by 2060, so it was assumed that all conventional energy sources would be converted to new energy sources by 2060. GHG emissions could be reduced through the application of organic fertilizers by 16%, slow-released fertilizers (such as urea formaldehyde, isobutylidene diurea etc.) by 25% and inhibitor fertilizers (such as chloromethyl pyridine, dicyandiamide etc.) by 49%37,38,39. In the context of carbon neutrality scenarios, N2O emissions were estimated by multiplying carbon emissions data by emissions reduction rate when using organic, slow-release and inhibitor fertilizers. However, due to lack of data on emissions factors for producing organic fertilizer, slow-released fertilizer, inhibitor fertilizer, we considered no difference in emissions of producing stage in our study. The carbon emissions of renewable energies in production didn’t consider due to lake of emissions factors. And this study did not consider the impact of technological advances and climate change on apple yields and soil carbon sequestration (Table 2).

Statistical analysis and graphing

In this study, Microsoft excel 2019 was used for data aggregation and calculation, and R 4.3.0 was used for the Mann–Kendall trend test. The diagrams were produced using ArcGIS 10.4 and Origin 2021.

Results

Carbon emissions by functional unit

The spatial distribution characteristics of carbon emissions per unit area (CEA) and carbon emissions per unit yield (CEY) in 2021 are shown in Fig. 3a,b. Shanxi had the highest CEA, followed by Shaanxi, Hebei, Shandong and other provinces. The CEAs ranged from 3.83 to 7.94 t CO2eq ha−1. Beijing and Shanxi had the highest CEY, reaching 0.29 kg CO2eq kg−1. The CEYs of other provinces ranged between 0.11 and 0.22 kg CO2eq kg−1.

Composition of the carbon footprint in 2021 and temporal and spatial variation characteristics of CEY and CEA. (a) Spatial distribution of CEA in 2021. (b) Spatial distribution of CEY in 2021. (c) Composition of the carbon footprint for each province in 2021. (d) Temporal variation characteristic of composition of the carbon footprint. (e) Temporal variation characteristic of CEA and CEY.

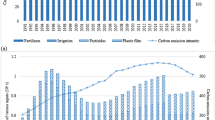

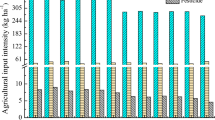

The composition of the carbon footprint of apple orchards in China showed that fertilizers and irrigation electricity were the primary components of the carbon footprint (Fig. 3c). On average, carbon emissions from fertilizers production, fertilizers in-field application, and irrigation electricity accounted for 21.3%, 33.1%, and 30.9%, respectively, followed by film, pesticides, and diesel fuel in 2021. On a temporal scale (Fig. 3d), the carbon emissions from fertilizers production and in-field application increased from 2002 to 2014, and then decreased to 3.18 t CO2eq ha−1 in 2021. The carbon emissions of irrigation electricity increased to 1.80 t CO2eq ha−1 in 2021.

Both CEY and CEA showed a tendency to fluctuate upward and then downward (Fig. 3e). The national average CEY increased from 0.20 kg CO2eq kg−1 in 2002 to 0.33 kg CO2eq kg−1 in 2014, then decreased to 0.23 kg CO2eq kg−1 in 2021. The national averaged CEA also increased from 2002 to 2014 and then decreased to 5.79 t CO2eq ha−1 in 2021.

Carbon emissions peak

From 2002 to 2021, the total national apple production showed an increasing trend (Fig. 4), while the national CE achieved a carbon peak (21.29 Mt CO2eq) in 2014, as CE showed a significant downward trend from 2014 to 2022 based on the MK trend test (P = 0.009) (Table 3). Furthermore, Shanxi and Liaoning reached their carbon emission peaks in 2013 and 2014, respectively, as they showed significant downward trends (P = 0.001 and P = 0.002), although with continuous increase in apple production. Henan’s apple production increased to a maximum in 2015, but the CE continued to decrease from the carbon peak year of 2004. Despite the continuous decline in apple production in Beijing, the peak in carbon emissions remained in 2014 (P = 0.001). Hebei reached its peak of carbon emissions in 2009 (P = 0.003). However, the CE of apple planting in Shandong, Shaanxi, and Gansu had not reached carbon peak.

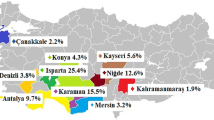

Planting advantage analysis

Carbon economic efficiency (CEE) could reflect the relationship between the environment and the economy (Fig. 5). Henan and Shandong had the higher CEE (5.23 and 5.18 yuan (kg CO2eq)−1) and the lowest CEY. Shaanxi had the highest CEE (5.55 yuan (kg CO2eq)−1), but the CEY was also higher than that of Henan and Shandong. Beijing and Hebei had moderate CEE, while Shanxi, Gansu, and Liaoning had lower CEE (1.1, 1.25 and 0.07 yuan (kg CO2eq)−1, respectively). By comprehensively comparing CEE and CEY, Henan and Shandong showed synergies between carbon emissions and economic development, indicating that both Henan and Shandong had planting advantages in apple orchards.

Pathways of emissions reduction

Figure 6 depicts the pathway of carbon emissions reduction at apple cultivation from 2021 to 2060. Based on scenario assumptions of the implementation of various alternative actions, the carbon emissions per unit area (CEA) caused by agricultural inputs and machines are projected to decrease from 5.40 t CO2eq ha−1 to 3.54 t CO2eq ha−1 by 2030 and 1.64 t CO2eq ha−1 by 2060, with a significant decrease of 69.6% from 2021 to 2060. Reduction of fertilizers application and transformation of traditional fertilizers to the low-carbon emissions fertilizers are key to reducing emissions in the apple orchards. GHG emissions from fertilizers would decrease from 3.17 in 2021 to 1.47 t CO2eq ha−1 in 2060. And the energy consumption of irrigation electricity and diesel would decrease to zero by 2060.

Discussion

Driving forces and targeted measures for apple cultivation

Understanding the drivers of GHG emissions is crucial for identifying targeted mitigation measures. Changes in factors such as planting scale and agricultural inputs could be the essential drivers leading to an increase or decrease in apple orchards GHG emissions. The drivers that determine changes in apple orchards emissions trend were shown in Figs. 3d and 4. The changes in the intensities of agricultural inputs resulted in increasing of carbon emissions of apple production from 2004 to 2014. By contrast, the carbon emissions were reduced during 2015–2021, which was driven by decreased intensity and inputs. Our results indicated a significant downward trend in carbon emissions after 2014, and apple cultivation in China had achieved the peak of carbon emissions in this year (Table 3). The peak in 2014 was mainly attributed to policy adjustments, such as the double reduction policy for fertilizers and pesticides implemented in 2015. Although there was limited research on whether Chinese apple production has reached its carbon peak, a few studies had identified carbon peaks in the agricultural sector40,41. However, the peak years reported in these studies are inconsistent, due to variations in planting areas, yields, agricultural inputs, and management practices42,43, and the carbon emissions varied across provinces, with CEA ranging from 3.83 to 7.94 t CO2eq ha−1 and CEY ranging from 0.11 to 0.29 kg CO2eq kg−1, respectively (Fig. 3). Therefore, the development of the apple industry in different provinces requires tailored emission reduction measures and low-carbon development models.

In 2021, the average CEY for apple orchards in China was 0.23 kg CO2eq kg−1 (Fig. 3), which was higher compared to Chile and France44,45. Furthermore, our result was lower than those of Italy, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, theUSA, and Japan46,47,48,49. The global average carbon emissions for apple orchards were reported as 0.36 kg CO2eq kg−147, which was higher than China. There are significant differences between different countries. We found emissions from fertilizers accounted for 54.4% of the carbon footprint in 2021 (Fig. 3), and fertilizers were considered the most important factor in apple production. The carbon emissions from fertilizer used in peach, banana, and orange cultivation accounted for 49% to 81% of their respective carbon footprints12, which was similar to our result. During the planting process, the average fertilizers application was 758.25 kg ha−1 in China, which was 36–40% higher than that of the USA and France44,49. The CEY from apples in Shaanxi, Gansu and Shanxi provinces were higher than those, the main reason was related to the higher application of fertilizers and irrigation. This was mainly related to the climatic and soil conditions in different regions50. Liu et al.35 recommended that local nitrogen management strategies can halve fertilizer use in China, so it is need specific fertilization in different apple planting regions according to the actual nutrient conditions. Reducing excessive fertilizers use may have a positive impact on carbon emissions and the quality of apples51. Therefore, optimizing fertilizers management, improving fertilizers utilization efficiency, and ensuring balanced nutrition provision are important targeted measures for reducing carbon emissions.

Irrigation, as a regulator of GHG emissions in farmland10,52, accounted for 30.9% of total GHG emissions in apple orchards in our study. The main reason was that apple trees are perennial and deciduous, with high water demands during the growth period. Irrigation can influence GHG emissions by affecting soil structure53 and soil respiration54,55. The conventional irrigation measures during apple cultivation include surface irrigation, alternate partial root-zone irrigation, surface drip irrigation and subsurface irrigation. Compared to traditional irrigation, drip irrigation could improve high-efficiency water use efficiency and apple yield56,57. Drip irrigation is identified as an effective method to improve water use efficiency, but excessive irrigation water can increase GHG emissions58. Thus, optimizing drip irrigation practices is necessary to mitigate GHG emissions from apple orchards. Excessive fertilizers application and traditional irrigation in apple cultivation is primarily carried out by small farmers in China, who often lack awareness of carbon emissions reduction and tend to manage apple orchards based on their own fertilization and irrigation habits43,59. Therefore, effective communication and collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and farmers are essential to promoting the implementation of targeted measures in rural areas.

Opportunities for low-carbon apple development

The development of the apple industry should consider the relationship between carbon emissions and economic development. To compare the planting advantages of different fruits and regions, it is essential to establish a universal indicator. However, CEA or CEY alone cannot directly assess the carbon efficiency and economic efficiency of apple cultivation. In this study, the CEE was introduced, and it comprehensively characterized the relationship between carbon emissions and the economy. CEE could serve as an indicator to evaluate the environmental and economic costs of agricultural products (Fig. 5). Our findings indicated that Henan and Shandong had higher growing advantages due to their higher CEE and lower CEY. In the process of reducing carbon emissions, it is crucial to ensure steady economic progress. A development model that balances GHG emissions reduction with economic efficiency improvement is recommended60,61. Therefore, CEE can be an effective indicator for assessing the growing advantages of agricultural products.

Meeting future food demand with lower GHG emissions and achieving high-quality economic development requires improving the overall efficiency of the economy and the environment62,63. This study outlined potential future developments for the apple industry and proposes strategies to reduce its carbon footprint (Fig. 6). The reduction of fertilizers application, the increase in the proportion of new fertilizers (e.g., organic fertilizers, slow-released fertilizers and inhibitor fertilizers) and the energy restructuring are of critical importance in the context of low-carbon apple development. The results of this study are similar to those of other studies, showing that the use of slow and controlled release fertilizers, improved water and fertilizers use efficiency and a shift in the energy mix could decrease the emissions of agriculture by 206064. Therefore, the promotion of low-carbon technologies will facilitate the apple industry’s transition towards low-carbon development.

Limitation and possibilities

This study has certain limitations and uncertainties. CH4 emissions from orchards could be monitored by static tanks, and the results of relevant literature studies showed that methane emissions in drylands showed a negative growth trend (− 2.47 to − 0.4 kg CH4 ha−1)65,66, while few studies calculated CH4 emissions in dryland. Additionally, although apple trees and soil possess significant carbon sequestration potential67,68,69, research on the carbon sequestration of trees in orchard is limited and exhibits significant variability. And there is a lack of data on soil nutrient conditions and changes in soil organic matter across different provinces. Consequently, the carbon sequestration of both soil and trees was not incorporated into in this study. Therefore, Monitoring carbon emissions and carbon sequestration from different orchards in the future will be necessary to accurately assess the carbon emissions of apple orchards. In addition, due to the lack of emission factors in the production process of agricultural inputs such as new fertilizers and renewable energy, deviations would be caused to the estimation process in the scenario hypothesis. And the adjustment of the energy structure from production would be beneficial to reduce the carbon emissions of agricultural inputs to achieve green low-carbon development. We suggest to establish a complete emission factor system in LCA to accurately estimate the carbon emissions of different processes in the future. Despite these limitations, the findings of this study are still reliable and provide valuable insights into the environmental and economic costs of Chinese apple cultivation. This study sheds light on the current state of apple orchards in terms of carbon emissions and serves as a theoretical foundation for achieving sustainable development in apple orchards.

With the growing concern about the problem of climate warming, low-carbon planting will become an important trend in the future development of agriculture. By adopting advanced technologies such as intelligent irrigation and precise fertilizers application, not only improve the efficiency of agricultural production, but also reduce the waste of water and fertilizers, which in turn will reduce the pressure on the environment. And the transformation and development of agriculture should strengthen the adjustment and optimization of energy structure and realize automation, intelligence and precision in the process of agricultural production through the technological fusion of new technologies and new industries. The future development of agriculture should be based on scientific and technological innovation as the main force, and green development as a practical requirement, in order to achieve green, high-quality development of agriculture.

Conclusions

This study employed a life cycle assessment method to quantitatively calculate the carbon footprint of apple orchards in China. The analysis considered temporal and spatial changes in carbon emissions and identified the carbon emissions peak for apple cultivation. The results indicated that the carbon emissions from apple cultivation in China showed a “low–high–low” trend, with the peak occurring in 2014. Fertilizers and irrigation electricity were identified as significant contributors to the carbon footprint of apple orchards. The averaged CEA and CEY in 2021 were 5.79 t CO2eq ha−1 and 0.23 kg CO2eq kg−1, respectively. The assessment of the relationship between CEE and CEY revealed significant variations in the growing advantages of apple cultivation across different regions. Future scenario analysis showed that the carbon emissions of apple trees will be decreased through optimizing fertilizers and energy restructuring. The findings highlight opportunities for low-carbon development in the apple industry through collaboration among farmers, scientists, and policymakers to implement targeted mitigation measures such as fertilization and irrigation in specific regions.

Data availability

All data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author (email: liyingchun@caas.cn). Data are derived from the agricultural production data set provided by the National Bureau of Statistics (China).

References

Bai, X. G. et al. Assessing fertilizer use efficiency and its determinants for apple production in China. Ecol. Indic. 104, 268–278 (2019).

USDA. Fresh Apples, Grapes, and Pears: World Markets and Trade. https://www.fas.usda.gov/data (United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2022).

IPCC. Climate change 2022 Mitigation of Climate Change; Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (2022).

Toensmeier, E. Perennial staple crops and agroforestry for climate change mitigation. Integrating landscapes: Agroforestry for biodiversity conservation and food sovereignty. Adv. Agrofor. 12, 1 (2017).

Guo, C. et al. Carbon footprint analyses and potential carbon emission reduction in China’s major peach orchards. Sustainability 10, 2908 (2018).

Huang, W. et al. Carbon footprint of cotton production in China: Composition, spatiotemporal changes and driving factors. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153407 (2022).

Zhang, D., Shen, J., Zhang, F., Li, Y. & Zhang, W. Carbon footprint of grain production in China. Sci. Rep. 7, 4126 (2017).

Chen, X. H. et al. Carbon footprint of a typical pomelo production region in China based on farm survey data. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 124041 (2020).

Frankowska, A., Jeswani, H. K. & Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of fruits consumption in the UK. J. Environ. Manag. 248, 109111 (2019).

Stres, B. et al. Influence of temperature and soil water content on bacterial, archaeal and denitrifying microbial communities in drained fen grassland soil microcosms. Fems Microbiol. Ecol. 66, 110–122 (2008).

Vinyes, E. et al. Life cycle assessment of apple and peach production, distribution and consumption in Mediterranean fruit sector. J. Clean. Prod. 149, 313–320 (2017).

Yan, M. et al. Farm and product carbon footprints of China’s fruit production—life cycle inventory of representative orchards of five major fruits. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 4681–4691 (2016).

Li, Y. P. et al. Exploring the environmental impact of crop production in China using a comprehensive footprint approach. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153898 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Identifying the main crops and key factors determining the carbon footprint of crop production in China, 2001–2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 172, 105661 (2021).

Liu, D., Zhang, W. S., Wang, X. Z., Guo, Y. J. & Chen, X. P. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential of hybrid maize seed production in northwestern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 29, 17787–17798 (2022).

Wu, H. J. et al. The influence of crop and chemical fertilizer combinations on greenhouse gas emissions: A partial life-cycle assessment of fertilizer production and use in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168, 105303 (2021).

Yang, W. J. et al. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing yield through manure substitution and supplemental irrigation in dryland of northwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 332, 107937 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from vegetables production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 317, 128449 (2021).

NBSC. China Rural Statistical Yearbook. http://www.stats.gov.cn/ (China Statistic Press, National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2003–2022).

ISO. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (2006).

NDRC. China Agricultural Products Cost-Benefit Yearbooks. http://www.stats.gov.cn/ (China Statistic Press, National Development and Reform Commission of China, 2003–2022).

Chen, S., Lu, F. & Wang, X. K. Estimation of greenhouse gases emission factors for China’s nitrogen, phosphate, and potash fertilizers. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 6371–6383 (2015).

Lin, K. T., Zhu, C. Z. & Chen, R. K. Research on the space-time differences of carbon sink of sugarcane industry in China. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res 35, 241–245 (2015).

Zhang, G., Lu, F., Huang, Z. G., Chen, S. & Wang, X. K. Estimations of application dosage and greenhouse gas emission of chemical pesticides in staple crops in China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 27, 2875–2883 (2016).

Li, B. Study on the Carbon Emission of Agricultural Land Utilization and Emission Reduced Policy in China. https://www.cnki.net/ (Hua Zhong Agricultural University, 2011).

NDRC. Accounting Methods and Guidelines for Corporate Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Food, Tobacco, Alcohol, Beverages, and Tea. https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/ (National Development and Reform Commission of China, 2015).

NDRC. Average CO2 Emission Factors for China’s Regional Grids in 2011 and 2012. http://www.stats.gov.cn/ (2014).

IPCC. Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Volume 4 Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use. https://www.ipccnggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/vol4.html (2019).

Li, S. T. & Ji, Y. J. Characteristics of nutrient input/output and nutrient balance in different regions of China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 44, 4207–4229 (2011).

Zhao, C. et al. Spatial patterns of net greenhouse gas balance and intensity in Chinese orchard system. Sci. Total Environ. 779, 146250 (2021).

Adeloye, A. J. & Montaseri, M. Preliminary streamflow data analyses prior to water resources planning study/Analyses préliminaires des données de débit en vue d’une étude de planification des ressources en eau. Hydrol. Sci. J. 47(5), 679–692 (2002).

Zhang, N. et al. Peaking characteristics and enlightenment based on carbon peak countries. China Environ. Sci. 42, 1912–1921 (2022).

MOA (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China). The Action Plan for Reducing Fertilizer and Pesticide Utilization by 2025. http://www.moa.gov.cn/ (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. A steady-state N balance approach for sustainable smallholder farming. PNAS 118, e2106576118 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Localized nitrogen management strategies can halve fertilizer use in Chinese staple crop production. Nat. Food 5, 825–835 (2024).

EFC (Energy Foundation China). Synthesis Report 2020 on China’s Carbon Neutrality: China’s New Growth Pathway: From 14th Five Year Plan to Neutrality. https://www.efchina.org/Reports-en/report-lceg-20201210-en (2020).

Fan, D. et al. Global evaluation of inhibitor impacts on ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 28(17), 5121–5141 (2022).

Hei, Z. et al. Full substitution of chemical fertilizer by organic manure decreases soil N2O emissions driven by ammonia oxidizers and gross nitrogen transformations. Glob. Change Biol. 29(24), 7117–7130 (2023).

Lü, H. D., Wang, X. Y., Pan, Z. L. & Zhao, S. C. Assessment of the crucial factors influencing the responses of ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions to controlled release nitrogen fertilizer: A meta-analysis. J. Integr. Agric. 22(11), 3549–3559 (2023).

Chen, X., Shuai, C. Y., Wu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Analysis on the carbon emission peaks of China’s industrial, building, transport, and agricultural sectors. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 135768 (2020).

Hu, Y. C., Su, M. R. & Jiao, L. M. Peak and fall of China’s agricultural GHG emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 389, 136035 (2023).

Liu, Z. J. et al. Current status of fertilization, distribution of N and P in soil profiles and techniques for reducing fertilizer application and improving efficiency in China’s apple orchards. J. Plant Nutr. 27, 1294–1304 (2021).

Pang, J. et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils under traditional cropland and apple orchard in the semi-arid Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 269, 116–124 (2019).

Alaphilippe, A., Simon, S., Brun, L., Hayer, F. & Gaillard, G. Life cycle analysis reveals higher agroecological benefits of organic and low-input apple production. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 33, 581–592 (2012).

Iriarte, A., Yáñez, P., Villalobos, P., Huenchuleo, C. & Rebolledo-Leiva, R. Carbon footprint of southern hemisphere fruit exported to Europe: The case of Chilean apple to the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 293, 126118 (2021).

Cerutti, A. K., Bruun, S., Donno, D., Beccaro, G. L. & Bounous, G. Environmental sustainability of traditional foods: The case of ancient apple cultivars in Northern Italy assessed by multifunctional LCA. J. Clean. Prod. 52, 245–252 (2013).

Clune, S., Crossin, E. & Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 766–783 (2017).

Stoessel, F., Juraske, R., Pfister, S. & Hellweg, S. Life cycle inventory and carbon and water FoodPrint of fruits and vegetables: Application to a Swiss retailer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3253–3262 (2012).

Venkat, K. Comparison of twelve organic and conventional farming systems: A life cycle greenhouse gas emissions perspective. J. Sustain. Agric. 36(6), 620–649 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Preliminary views of region plantation for apple production in China referred to fruit quality and orchard income. China Fruits 11, 1–5 (2022).

Wang, G. Y., Zhang, X. Z., Wang, Y., Xu, X. F. & Han, Z. H. Key minerals influencing apple quality in Chinese orchard identified by nutritional diagnosis of leaf and soil analysis. J. Integr. Agric. 14(5), 864–874 (2015).

Butterbach-Bahl, K., Baggs, E. M., Dannenmann, M., Kiese, R. & Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: How well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 1621 (2013).

Trost, B. et al. Irrigation, soil organic carbon and N2O emissions. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 33, 733–749 (2013).

Oertel, C., Matschullat, J., Zurba, K., Zimmermann, F. & Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils: A review. Chemie Erde 76(3), 327–352 (2016).

Sapkota, A., Haghverdi, A., Avila, C. C. E. & Ying, S. C. Irrigation and greenhouse gas emissions: A review of field-based studies. Soil Syst. 4, 20 (2020).

He, Z. et al. Optimization of apple irrigation and N fertilizer in Loess Plateau of China based on ANP-EWM-TOPSIS comprehensive evaluation. Sci. Hortic. 311, 111794 (2023).

Sun, M., Gao, X., Zhang, Y., Song, X. & Zhao, X. A new solution of high-efficiency rainwater irrigation mode for water management in apple plantation: Design and application. Agric. Water Manag. 259, 107243 (2022).

Tang, W. Z. et al. Effects of water allocation process on greenhouse gas emissions in drip-irrigated apple orchards on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 338, 108077 (2022).

Meng, Y. D., Xu, F. Y., Yang, F. & Gong, X. X. Situation of fertilizer application and analysis of fertilizer saving potential in crop farming in China. Phosphate Compd. Fertil. 30, 1–4 (2015).

Li, S., Wu, J. C., Wang, X. Q. & Ma, L. Economic and environmental sustainability of maize-wheat rotation production when substituting mineral fertilizers with manure in the North China Plain. J. Clean. Prod. 271, 122683 (2020).

Van Grinsven, H. et al. Costs and benefits of nitrogen for Europe and implications for mitigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3571–3579 (2013).

Hong, J. et al. Water, energy, and carbon integrated footprint analysis from the environmental-economic perspective for apple production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 368, 133184 (2022).

Meng, M., Fu, Y. & Wang, L. Low-carbon economy efficiency analysis of China’s provinces based on a range-adjusted measure and data envelopment analysis model. J. Clean. Prod. 199, 643–650 (2018).

Chen, M., Cui, Y., Jiang, S. & Forsell, N. Toward carbon neutrality before 2060: Trajectory and technical mitigation potential of non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions from Chinese agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 368, 133186 (2022).

Xie, B. H. et al. Effects of N fertilizer application on soil N2O emissions CH4 uptake: A two-year study in an apple orchard in eastern China. Atmosphere 8, 181 (2017).

Song, Q. L. et al. A three-year record of CO2, CH4 and N2O in maize fields influenced by mulching methods on the loess plateau, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 367, 108963 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Four pathways towards carbon neutrality by controlling net greenhouse gas emissions in Chinese cropland. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 186, 106576 (2022).

Giuseppe, M., Cristos, X., Vitale, N. & Bartolomeo, D. Orchard management, soil organic carbon and ecosystem services in mediterranean fruit tree crops. Sci. Hortic. 217, 92–101 (2017).

Wu, T. et al. Carbon sequestration by fruit trees—Chinese apple orchards as an example. PLoS ONE 7, 38883 (2012).

Funding

This work was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAASZDRW202417, CAAS-CSGLCA-202301); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (D41105115); and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Y2020PT05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingyu Zhang: Data curation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Yanqun Wang: Visualization. Yingchun Li: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. Zhengping Peng: Writing—review & editing. Fen Ma: Methodology. Xue Han: Formal analysis. Kuo Li: Investigation. Mingyue Zhao: Investigation and data curation. Xin Ma: Project administration and Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Li, Y. et al. Carbon emissions peak of China’s apple cultivation achieved in 2014: a comprehensive analysis and implications. Sci Rep 15, 12141 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88885-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88885-6