Abstract

The proliferation of multidrug-resistant, metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (MBL-producing K. pneumoniae) poses a major threat to public health resulting in increasing treatment costs, prolonged hospitalization, and mortality rate. Treating such bacteria presents substantial hurdles for clinicians. The combination of Aztreonam (ATM) and ceftazidime/avibactam (CAZ/AVI) is likely the most successful approach. The study evaluated the in vitro activity of CAZ/AVI in combination with ATM against MBL-producing K. pneumoniae clinical isolates collected from Suez Canal University Hospital patients. Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae were isolated and identified from different specimens. The presence of metallo-β-lactamases was detected phenotypically by modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) testing, and genotypically for the three metallo-β-lactamase genes: blaNDM, blaIMP, and blaVIM by conventional PCR method. The synergistic effect of CAZ/AVI with ATM against MBL-producing K. pneumoniae was detected by ceftazidime-avibactam combination disks and E-test for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Out of the 65 K. pneumoniae isolates recovered, 60% (39/65) were carbapenem-resistant (CRKP). According to the mCIM and eCIM tests, 89.7% (35/39) of CRKP isolates were carbapenemase-positive, and 68.6% (24/35) were metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-positive. By using the conventional PCR, at least one of the MBL genes was present in each metallo-bata-lactamase-producing isolate: 8.3% carried the blaVIM gene, 66.7% the blaNDM, and 91.7% the blaIMP gene. After doing the disk combination method for ceftazidime-avibactam plus Aztreonam, 62.5% of the isolates shifted from resistance to sensitivity. Also, ceftazidime/avibactam plus Aztreonam resistance was reduced markedly among CRKP using the E-test. The addition of Aztreonam to ceftazidime/avibactam is an effective therapeutic option against MBL-producing K. pneumoniae.

Clinical Trials Registry: Pan African Clinical Trials Registry. Trial No.: PACTR202410744344899. Trial URL: https://pactr.samrc.ac.za/TrialDisplay.aspx?TrialID=32000

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, particularly strains producing metallo-β-lactamase, has become a challenge of particular importance in clinical practice worldwide. MBL-positive CRKP exhibits resistance to nearly all beta-lactam antibiotics, including carbapenems, leaving very limited therapeutic options1. Several recent studies have pointed out the role of the blaNDM, blaIMP, and blaVIM genes in determining this resistance, with blaNDM being the most widespread in many countries2. Ceftazidime/Avibactam in combination with Aztreonam has been an effective combination against MBL-mediated resistance since Aztreonam is stable against MBLs and Ceftazidime/Avibactam inhibits serine beta-lactamases3. The efficacy of this combination against MBL producers among CRKP in our region remains underexplored.

The global rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria has heightened concerns about infections that are untreatable with conventional antibiotics. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP), in particular, poses a serious public health threat, increasing mortality rates among critically ill patients and exacerbating the financial burden of hospital stays worldwide. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the infection rate of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) is 57/100,000, with in-hospital mortality rates of 33.50% for nosocomial infections and 43.10% for bloodstream infections4. Notably, approximately 50% of patients with K. pneumoniae pneumonia succumb to the infection5. In Egypt, CRKP prevalence ranges from 31.3% in university hospitals6 to 25.4% in tertiary care hospitals7, while in Greece, the rate reaches 66.3%8.

One or a combination of the following mechanisms mediate resistance to carbapenems: (1) the carbapenemases production which hydrolyzes carbapenems, such as the serine β-lactamases Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) (Ambler class A), metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) including New Delhi MBL (NDM) or Verona integron-encoded MBL (VIM), imipenemase (IMP) (Ambler class B) and OXA-48-like carbapenemases (Ambler class D), and less frequently, the production of Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and/or Ambler class C β-lactamase (AmpC) enzymes; (2) reduced permeability as a result of defective expression of specific outer membrane proteins; (3) drug efflux across the outer membrane; and (4) the production of a modified or low-affinity target, which is more significant in Gram-positive bacteria9. MBLs, out of all the carbapenemases, are currently the more concerning because of their ability to hydrolyze all β-lactams and carbapenems except Aztreonam (monobactam), and they are not inhibited by boronic acid inhibitors (vaborbactam), novel diazabicyclooctane (DBO) β-lactamases (avibactam, relebactam), or classical serine β-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., clavulanic acid, tazobactam, sulbactam)10.

Aztreonam has been the only monocyclic lactam antibiotic that is currently accessible for clinical use and effective against MBLs since it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 198611. Unfortunately, most MBL-Enterobacterales also co-harbor additional ESBL or AmpC β-lactamase genes, which makes monobactam ineffective against MBL producers and imparts Aztreonam resistance12. Ceftazidime/avibactam is a combination of beta-lactamase inhibitor (avibactam) and cephalosporin (ceftazidime). Avibactam inhibits serine carbapenemases such as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), AmpC beta lactamases, OXA-48, and ESBLS. By blocking class A, class C, and some class D beta-lactamases, avibactam restores ceftazidime’s action and overcomes resistance brought on by carbapenemases such as KPC. The combination, however, is ineffective against class B beta-lactamases, including VIM, NDM, and other metallo-beta lactamases13. Aztreonam is stable to the hydrolysis of MBLs like NDM, and avibactam protects Aztreonam from hydrolysis by serine β-lactamases, so the combination of Ceftazidime/avibactam plus Aztreonam is a valuable option to treat infections by beta-lactamase-producing Gram-negative pathogens producing serine β-lactamases, MBLs, or both14.

Currently, there are no commonly accepted antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods to assess the synergic effect of CAZ/AVI plus ATM. “Time-kill kinetics” and “checkerboard” assays are labor-intensive, complicated, and interpretation-challenging testing procedures of synergistic effectiveness. The “E-strip-disc diffusion”, “E-strip stacking”, and “E-strip cross” assays are somewhat subjective, not very labor-intensive, and accurate15.

This study aims to evaluate the in vitro activity of CAZ/AVI in combination with ATM against MBL-producing K. pneumoniae clinical isolates collected from patients of Suez Canal University Hospital by disc diffusion and E-test methods.

Subject and methods

Study population and design

This observational cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at the Suez Canal University Hospitals in Ismailia, Egypt, from December 2022 to June 2024. Samples were collected from different intensive care units (ICUs) and other hospital wards and were processed in the Medical Microbiology and Immunology Department laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University.

Ethical considerations

The current study was implemented in coordination with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was gained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt, # 5060. The patients provided written informed consent, which addressed all the steps of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. The minor patient’s informed consent was obtained from a parent, which addressed all the steps of the study and their right to withdraw at any time.

Inclusion criteria

Immunocompromised, debilitated patients, patients with serious underlying diseases of both sexes (male and female), and patients of all age groups who showed signs and symptoms of pyogenic infections and agreed to participate were included in this study. Samples included urine from catheterized and non-catheterized patients, respiratory specimens from intubated and non-intubated patients, Pus and wound swabs, pleural fluid, and blood.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who received antibiotic treatment in the last 48 h or refused to participate were excluded.

Study procedures

Full history taking, and thorough physical examination

All enrolled patients were asked and examined for underlying medical conditions or certain types of healthcare exposures, such as:

-

Immunocompromising conditions.

-

Recent frequent or prolonged stays in health care settings.

-

Invasive medical devices such as breathing tubes, feeding tubes, and central venous catheters.

-

Open wounds.

-

A history of taking certain antibiotics for long periods.

For every patient admitted to internal wards or intensive care units, the following data was found age, length of stay, number of days needed for mechanical ventilation, and survival until hospital discharge. Additionally, microbiological results were obtained to identify K. pneumoniae-positive cultures.

Samples collection and preservation

Various samples (urine, sputum, endotracheal aspirate, pleural fluid, pus, and wound exudate) were collected aseptically16 throughout the study for presumptive K. pneumoniae isolation and identification. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory in sterile containers and stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 2 h before processing to maintain sample integrity and prevent bacterial overgrowth. A total of 365 clinical samples were analyzed for bacterial isolation.

Bacterial isolation and identification

For bacterial isolation, all collected samples were inoculated into blood agar and MacConkey agar media (Oxoid, UK) and incubated aerobically at 35 ± 2℃ for 24 h. For initial identification of the isolates, they underwent a hanging drop test, and biochemical tests including “catalase, citrate, oxidase, oxidative fermentation, indole, Methyl Red (MR), Voges-Proskauer (VP), urease, H2S production, and gelatin hydrolysis, pigment, and MUG test”.

Phenotypic detection of metallo-β-lactamases by modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) testing

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) adopted “modified carbapenem inactivation method” (mCIM) and “EDTA-modified carbapenem inactivation method” (eCIM) as a combination phenotypic test to detect and differentiate between serine and metallo-based carbapenemases for Enterobacterales17.

One “microliter loopful of the test isolate” was suspended in 2 ml of “trypticase soy broth” (TSB), and a “meropenem disc” was added to the suspension. The culture was incubated for 4 h at 35 °C. The control strain of K. pneumoniae MGH 78,578 (a carbapenem-sensitive strain) was adjusted in sterile saline with 0.5 “McFarland standard and streaked” in three directions on “Mueller–Hinton Agar” (MHA) plates to ensure an even and uniform cell lawn. After transferring the disc from the TSB suspension onto an MHA plate, the plate was left to incubate for the full night at 35 °C. To achieve a “final EDTA concentration” of 5 mM for every isolate, 20 µL of the 0.5 M EDTA was filled into a second 2-mL TSB tube intended for the eCIM test, which was labeled. Then the same steps as in mCIM were performed. The mCIM and eCIM tubes were processed in parallel. The “meropenem discs” from the mCIM and eCIM tubes were placed on the same MHA plate inoculated with the meropenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae MGH 78,578 indicator strain. Following incubation, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured.

For the mCIM test

Carbapenemase positive test strain: if it showed an inhibition zone 6–15 mm or the presence of pinpoint colonies within a 16–18 mm zone. Carbapenemase negative test strain: if it showed inhibition zone ≥ 19 mm. Intermediate test strain: if it showed inhibition zone 16-18 mm.

For the eCIM test

When the mCIM test showed positive results; metallo-β-lactamase positive strain: a zone diameter increases of ≥ 5 mm for eCIM in comparison to mCIM. Metallo-β-lactamase negative strain: A ≤ 4-mm increase in zone diameter for eCIM compared to mCIM.

Molecular detection of metallo-β-lactamase genes by conventional PCR

Bacterial DNA was extracted using the “QIAprep Miniprep DNA Purification Kit” (“QIAGEN, Germany”) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the detection of blaNDM, blaIMP, and blaVIM with a set of primers18 as described in Table 1. The reaction mixture was prepared in a total volume of 25 μl including:

-

5 μl of template DNA,

-

12.5 μl of 2X ABT Red master mix (Applied Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Egypt), and

-

2 μl of both forward and reverse primers

-

the volume was then completed with sterile distilled water up to 25 μl.

Reaction mixtures without a DNA template served as negative controls. Amplification was carried out in a thermal cycler (Peltier Thermal cycler, MJ Research, U.S.A). PCR cycling conditions included “initial denaturation” at 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 56–58 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min for extension, and a final polymerization at 72 °C for 10 min”. Amplified fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel at 5 V/cm for 2 h and observed by a UV transilluminator.

Antimicrobial sensitivity testing

Standard disc diffusion method

Phenotypic detection of antibiotic resistance was done using the “Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method” on Mueller Hinton agar (Oxoid, UK) and incubated at 35 °C for 16–18 h according to Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines of CLSI, 2022, control strain of K. pneumoniae MGH 78,578 was used15. The antibiotics used: Ampicillin (10 µg), Amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 µg), Cefepime (30 µg), Ceftazidime (30 µg), Cefotaxime (30 µg), Imipenem (10 µg), Meropenem (10 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Amikacin (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Levofloxacin (5 µg). All antibiotics were purchased from “Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, USA)”.

Ceftazidime/avibactam combination method with Aztreonam discs

The test organism was first added to the MHA plates through inoculation. Following that, 30 µg/20 µg of ceftazidime/avibactam antibiotic discs were placed on them, and they were incubated for 1 h at 35 ± 2 °C. After this incubation, the ceftazidime/avibactam disks were removed, and the Aztreonam discs were placed in the same location and incubated for 1 h at 35 ± 2 °C. The 1-h duration was sufficient for antibiotic diffusion into the medium, as confirmed by the observed zones of inhibition. The following day, a zone of inhibition was noted following CLSI 2024 guidelines for disc diffusion testing, synergy was considered present if the zone diameter of the replacement AZT disc was ≥ 21 mm19.

MIC of ceftazidime/avibactam alone and in combination with Aztreonam

For the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination, ceftazidime/avibactam and Aztreonam E-test strips were utilized. After an hour of incubation, one of the two ceftazidime/avibactam E-test strips was removed, and the imprint of the removed E-test strip was covered with an Aztreonam E strip. The plates underwent another 18-h incubation period at 35 ± 2 °C.

Statistical analysis

Data was coded and entered into the computer statistical program. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 (Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data presentation was performed via tables and graphs. Qualitative data were presented as numbers and percentages while quantitative data were presented as mean ± Standard Deviation. Fisher’s exact tests were used for qualitative variables. ANOVA test was used to compare the Zone diameter between groups and Tukey Post Hoc test was used to assess the significance between each two groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation, identification, and phenotypic detection of K. pneumoniae isolates

A total of 365 examined clinical samples were analyzed for bacterial isolation. A total of 65 K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered. 60% (39/65) of the isolates were CRKP identified by either being meropenem and/or imipenem resistant.

The patients’ ages ranged from 16 to 75, with a mean of 44.6 and a standard deviation of ± 20.4. The CRKP isolates were obtained more frequently from males (61.5%) than females (38.5%). The highest rate of CRKP isolation was from endotracheal aspirates (46.7%), while the lowest rate was from sputum and blood (10%) from ICUs of Suez Canal University hospitals (Table 2).

Preliminary isolation and identification of K. pneumoniae were based on Gram-negative staining and colony morphology. The isolates were Gram-negative, non-motile bacilli, forming small (3–5 mm), gray, moist, and often mucoid colonies on blood agar. On MacConkey agar, the colonies appeared pink-yellow due to lactose fermentation. Biochemical tests confirmed the identification of K. pneumoniae, with positive results for catalase, citrate, VP, urease, and MUG tests, and negative results for oxidase, indole, MR, H2S production, gelatin hydrolysis, and pigment production. The isolates were also fermentative in oxidative fermentation tests.

Phenotypic detection of metallo-β-lactamases by modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) testing

Modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) tests resulted in 35 (89.7%) CRKP isolates showed a zone diameter of 6–15 mm for meropenem disc and interpreted as carbapenemase positive, while 1 (2.6%) isolate showed a 17 mm zone diameter that was interpreted as carbapenemase intermediate and 3 (7.7%) isolates showed zone diameters of ≥ 19 mm and interpreted as carbapenemase negative (Table 3). A total of 24 isolates (68.6%) showed an increase of zone diameter ≥ 5 mm after adding EDTA and they were considered Metallo-β-lactamase positive isolates (Table 4, Fig. 1).

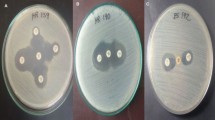

Molecular detection of metallo-β-lactamase genes by conventional PCR

By conventional PCR, molecular testing was done to detect the 3 MBL genes in the 24 Metallo-β-lactamase positive isolates. All 24 isolates harbored at least one of the MBL genes (blaIMP, blaNDM, and blaVIM). A total of 22 isolates (91.7%) harbored blaIMP gene, 16 isolates (66.7%) harbored blaNDM and 2 isolates (8.3%) harbored blaVIM (Table 4, Fig. 2A–C). Full-length gel images with membrane edges are included in the Supplementary Information file. The gels were not physically cut before imaging.

Detection of metallo-beta lactamase genes by agarose gel electrophoresis. Lane M shows a 100 bp molecular strand DNA ladder, (A) blaNDM gene; All Lanes show positive specimens (236 bp), except lane (3, 5), (B) blaIMP gene; All Lanes show positive specimens (587 bp), (C) blaVIM gene; 2 Lanes show positive specimens (382 bp).

Antibiotic susceptibility test

Standard disk diffusion method

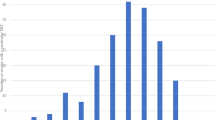

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was done on the 39 K. pneumoniae isolates by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method. The highest resistance was for Ampicillin, Amoxicillin-clavulanate, and Ceftazidime antibiotics as they showed 100%, 94.9%, and 82.1% resistance respectively. In contrast, the least resistance was for Cefepime 28.2% (Table 6, Fig. 3).

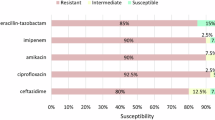

Ceftazidime/avibactam susceptibility testing alone and in combination with aztreonam (disc replacement method)

None of the isolates showed zone diameter ≥ 21 mm when testing Aztreonam disc susceptibility by the Kirby-Bauer method, while 2 isolates (8.3%) were ≥ 21 mm for Ceftazidime-Avibactam disc. However, after doing the combination method for Ceftazidime-Avibactam plus Aztreonam, synergy was observed in 15/24 (62.5%) of the resistant isolates, inhibition zone became ≥ 21 mm (Tables 7 and 8).

None of the sensitive isolates carried the blaVIM gene. None of the isolates showed zone diameters ≥ 21 mm for Aztreonam alone, while 2 isolates (8.3%) were sensitive to Ceftazidime/Avibactam alone. However, the combination of Ceftazidime/Avibactam + Aztreonam resulted in 15 isolates (62.5%) becoming sensitive, demonstrating a significant synergistic effect (p < 0.001). Among the 15 isolates that became sensitive to the combination of Ceftazidime-Avibactam + Aztreonam (zone diameter ≥ 21 mm), 9 isolates (60%) harbored the blaIMP gene, and 6 isolates (40%) harbored the blaNDM gene (Tables 7 and 8).

MIC of ceftazidime/avibactam alone and in combination with aztreonam

When the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) antibiotic susceptibility test was done by E-test strips, it revealed MIC of ceftazidime/avibactam ranged from 8/4 to ≥ 64/4 µg/ml, while after doing the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam plus Aztreonam the MIC of all isolates ranged from ≤ 0.016/4 to 6/4 µg/ml (Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections, posing a significant threat to human health due to limited therapeutic options9. The combination of Ceftazidime/Avibactam (CAZ/AVI) and Aztreonam (ATM) has emerged as a crucial therapeutic option for MBL-producing CRKP, as it neutralizes class A, C, and some class D beta-lactamases while combating MBLs20. This study evaluated the in vitro efficacy of CAZ/AVI + ATM against MBL-producing CRKP isolates from Suez Canal University Hospital, Egypt.

The study was carried out on 365 clinical samples, a total of 65 K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered (17%). 60% (39/65) of the isolates were carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) as identified by either being meropenem- and/or imipenem-resistant. The age of the patients ranged from 16 to 75 years old, with a percentage of (61.5%) from male patients and (38.5%) from female patients (Table 2). The highest rate of CRKP isolation was from endotracheal aspirates (46.7%), while the lowest rate was from sputum and blood (10%) from the different ICUs (Table 2).

The CRKP prevalence has been reported worldwide. ICU hospitalization was found to be a significant risk factor for developing CRKP21,22,23,24. The disparities in prevalence rates may be related to changes in the hospital setting, the number of specimens examined, and the frequent use of carbapenems as empiric therapy in ICUs along with the antimicrobial stewardship program’s non-implementation. Studies from other hospitals in Egypt showed different prevalence rates of CRKP. It was 66%, 33.3%, 44.3%, and 14.2%, in Zagazig21,22, Mansoura23, Suez Canal24, and Al-Azhar25 University Hospitals respectively. The prevalence rate was 13.9% at the Egyptian National Cancer Institute-Cairo26. Comparably, other research revealed that the prevalence rate in New York and Greece was 20 and 40% respectively27,28. A study conducted in the USA revealed a higher result of 83%29.

The present study showed that the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) test showed that 35/39 (89.7%) CRKP isolates showed a zone diameter of 6–15 mm for meropenem disc and interpreted as carbapenemase positive, while 1/39 (2.6%) isolate showed a 17 mm zone diameter that was interpreted as carbapenemase intermediate and 3/39 (7.7%) isolates showed zone diameters of ≥ 19 mm and interpreted as carbapenemase negative (Table 3). The eCIM testing of the 35 carbapenemase-positive CRKP isolates showed that 24 isolates (68.6%) had an increase of zone diameter ≥ 5 mm after adding EDTA and they were considered Metallo-β-lactamase positive isolates (Table 4).

Previous studies have widely used the mCIM test for phenotypic carbapenemase detection. In Egypt, studies at Zagazig University hospitals reported 86% (49/57) and 89.1% (106/119) of CRKP isolates as carbapenemase-positive21,22, while Alexandria University Hospital found 70% (37/53) of isolates to be mCIM-positive, with 51% (19/37) confirmed as MBL-positive by eCIM30. In India, a study at a tertiary hospital revealed 96% (145/151) of CRKP isolates as mCIM-positive, with 98% (142/145) being eCIM-positive31. Similarly, studies in China reported 96.4% (402/417) and 88% (91/103) of isolates as mCIM-positive, with 26.4% (110/417) and 75% (68/91) being eCIM-positive, respectively32,33.

The modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) effectively identifies carbapenemases but cannot differentiate between serine and metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). To address this, the EDTA-modified carbapenem inactivation method (eCIM) was developed, enabling precise detection of MBLs. The combination of mCIM and eCIM tests distinguishes between serine carbapenemases (mCIM-positive, eCIM-negative) and MBLs (mCIM-positive, eCIM-positive)34,35. While mCIM is cost-effective, easy to perform, and requires no specialized equipment, its long incubation period (8 h to overnight) and inability to confirm carbapenemase class remains limitations17.

In the present study, by conventional PCR, molecular testing was done to detect the 3 MBL genes (blaIMP, blaNDM, and blaVIM) in the 24 Metallo-β-lactamase positive isolates. All 24 isolates (100%) harbored at least one of the MBL genes. A total of 22 isolates (91.7%) harbored blaIMP gene, 16 isolates (66.7%) harbored blaNDM and 2 isolates (8.3%) harbored blaVIM (Table 5, Fig. 2A-C).

The CRKP isolates have genes that encode carbapenemase, such as bla genes, in addition to a range of genes that confer resistance to medications other than β-lactams, rendering all antibiotics ineffective. Carbapenemases are classified into two classes according to the composition of their active sites: “serine-carbapenemases” which have “Serine” in the active site making the class A and class D, and the second category “Metallo-β-lactamases (MBL)” which have an active site including a zinc atom making the class B. The most commonly reported genes in class B MBL-producing strains are blaNDM, blaIMP, and blaVIM, while the most commonly reported genes in class A and D are blaKPC and blaOXA, respectively36. Currently IMP-producing and NDM-producing CRKP are well recognized. Nevertheless, there haven’t been many reports of CRKP when blaIMP and blaNDM coexist37,38,39. Unlike our findings, several studies in Egypt revealed that the most prevalent gene among CRKP isolates was the blaNDM gene21,40,41,42. In Uganda, blaVIM was the most amplified carbapenemase gene, while blaNDM was the least amplified one43. Meanwhile, it was reported in China that blaKPC was the most prevailing gene in K. pneumoniae44. In Turkey, the blaOXA-48 gene was the most predominant followed by blaNDM and blaVIM genes respectively. blaKPC and blaIMP genes were not identified 45,46. In Saudia Arabia, the most common carbapenemases were the blaOXA-48 and blaNDM genes. No blaKPC or blaIMP genes were detected47,48.

In the present study, antibiotic susceptibility testing was done on the 39 K. pneumoniae isolates by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method. All 39 CRKP isolates in the present study were multidrug-resistant (MDR). The highest resistance was for Ampicillin 39/39 (100%), Amoxicillin-clavulanate 37/39 (94.9%), Ceftazidime 32/39 (82.1%), and Cefotaxime 27/39 (69.2%) antibiotics. The most sensitive antibiotics were Cefepime 16/39 (41%) and Ciprofloxacin 14/39 (35.9%) (Table 6, Fig. 3).

Numerous investigations have also documented the noteworthy correlation between multidrug resistance and carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates whether locally in Egypt21,22,23,24,25,26 or worldwide32,49,50,51. An alarming elevated prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) “resistance to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes”, extremely drug-resistant (XDR) “resistance to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobials”, and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) “resistance to all agents in all antimicrobial classes”. Since pan-drug-resistant isolates are essentially unaffected by antibiotics, higher rates of morbidity and mortality are to be predicted, which is concerning52.

K. pneumoniae resistance to carbapenems arises from complex mechanisms, including increased efflux pump activity, altered outer membrane permeability, and the production of carbapenemases, which hydrolyze β-lactams and may include extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs). According to CLSI surveillance data, 50–60% of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales remain susceptible to cefepime53, which may be used to treat these isolates despite carbapenemase production54. However, cefepime susceptibility should alert clinicians to potential treatment failure, as carbapenem-resistant isolates often exhibit multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotypes and carry additional resistance factors. The expression of mobile genetic elements within carbapenemase genes further exacerbates resistance55, underscoring the urgent need for new antibiotics and synergistic combinations to combat these pathogens.

In our study, none of the isolates showed zone diameter ≥ 21 mm when testing Aztreonam disc susceptibility by the Kirby-Bauer method, while 2 isolates (8.3%) were ≥ 21 mm for Ceftazidime-Avibactam disc. However, after doing the combination method for Ceftazidime-Avibactam plus Aztreonam, synergy was observed in 15/24 (62.5%) of the resistant isolates, inhibition zone became ≥ 21 mm, indicating a shift from resistance to sensitivity. Among the 15 isolates that became sensitive to the combination of Ceftazidime-Avibactam + Aztreonam (zone diameter ≥ 21 mm), 9 isolates (60%) harbored the blaIMP gene, and 6 isolates (40%) harbored the blaNDM gene. None of the sensitive isolates carried the blaVIM gene, suggesting that the combination therapy is particularly effective against isolates carrying blaIMP and blaNDM genes (Tables 7 and 8). In addition, Ceftazidime-avibactam minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) using E-test strips, ranged from 8/4 to ≥ 64/4 µg/ml (resistant) when tested. However, when ceftazidime-avibactam plus Aztreonam was combined, the MIC ranged from ≤ 0.016/4 to 6/4 µg/ml (sensitive) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Previous studies revealed promising results of the combination of CAZ/AVI and ATM to treat carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Synergy was observed between CAZ/AVI and ATM disc in 33/35 (94.28%)56 and 60/60 (100%)57 of the carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella species isolates. Several recent investigations have also shown, through the use of various testing methodologies, the synergy between CAZ/AVI and ATM in MDR, XDR, and PDR Klebsiella species isolates15,58,59,60,61.

Ceftazidime/Avibactam, a third-generation cephalosporin coupled with a β-lactamase inhibitor, is a new and efficacious therapeutic alternative that exhibits broad-spectrum efficacy against serine β-lactamases but is degraded by Metallo-β-lactamases. Aztreonam, on the other hand, is vulnerable to hydrolysis by serine β-lactamases but stable in the presence of Metallo-β-lactamases. Thus, Ceftazidime/Avibactam + Aztreonam is a useful combination to treat infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria that produce serine β-lactamases and/or Metallo-beta-lactamases14.

This study has several limitations. First, the detection of resistance genes (blaNDM, blaIMP, and blaVIM) was performed using conventional PCR, which confirms their presence but does not provide detailed sequence information or identify specific variants. Future studies should include sequencing to characterize these genes further and explore potential mutations or variants. Second, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the sample size, though sufficient for preliminary analysis, could be expanded in future work to strengthen the statistical power of the results.

Conclusion

The novel combination of Ceftazidime/Avibactam (CAZ/AVI) and Aztreonam (ATM) demonstrates significant in vitro efficacy against Metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. This combination effectively overcomes resistance mediated by MBLs and serine β-lactamases, offering a promising therapeutic option for treating highly resistant CRKP infections. Nevertheless, more in vivo studies are still required to validate these findings and explore the clinical applicability of this combination therapy.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Karampatakis, T., Tsergouli, K. & Behzadi, P. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: virulence factors, molecular epidemiology and latest updates in treatment options. Antibiotics 12(2), 234 (2023).

ElBaradei, A. Co-occurrence of blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 among carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates causing bloodstream infections in Alexandria, Egypt. Egypt. J. Med. Microbiol. 31(3), 1–7 (2022).

Brauncajs, M., Bielec, F., Malinowska, M. & Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. Aztreonam combinations with avibactam, relebactam, and vaborbactam as treatment for New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales infections—In vitro susceptibility testing. Pharmaceuticals 17(3), 383 (2024).

Ahmadi, Z., Noormohammadi, Z., Behzadi, P. & Ranjbar, R. Molecular detection of gyrA mutation in clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Iran. J. Public Health 51(10), 2334 (2022).

Martin, R. M. & Bachman, M. A. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 4 (2018).

Taha, M. S. et al. Genotypic characterization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from an Egyptian University Hospital. Pathogens 12(1), 121 (2023).

Al-Baz, A. A., Maarouf, A., Marei, A. & Abdallah, A. L. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance profiles of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from tertiary care hospital, Egypt. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 88(1), 2883–2890 (2022).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2019) Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. https://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx?Dataset=27&HealthTopic=4. (Accessed 30 Jun 2022). (2022).

Hammoudi, H. D. & Ayoub, M. C. The current burden of carbapenemases: review of significant properties and dissemination among gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 9(4), 186 (2020).

Li, R., Chen, X., Zhou, C., Dai, Q. Q. & Yang, L. Recent advances in β-lactamase inhibitor chemotypes and inhibition modes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 242, 114677 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. In vitro activity of aztreonam–avibactam against metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae—A multicenter study in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 97, 11–18 (2020).

Salvia, T., Dolma, K. G., Dhakal, O. P., Khandelwal, B. & Singh, L. S. Phenotypic detection of ESBL, AmpC, MBL, and their co-occurrence among MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates. J. Lab. Phys. 14(03), 329–335 (2022).

Rajan, R., Rao, A. R. & Kumar, M. S. Ceftazidime-avibactam/aztreonam combination synergy against carbapenem-resistant gram-negative isolates: In vitro study. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 14(1), 16–21 (2024).

Garcia-Bustos, V., Cabañero-Navalón, M. D. & Lletí, M. S. Resistance to beta-lactams in gram-negative bacilli: relevance and potential therapeutic alternatives. Rev. Esp. Quim. 35(Suppl 2), 1 (2022).

Khan, A. et al. Evaluation of susceptibility testing methods for aztreonam and ceftazidime-avibactam combination therapy on extensively drug-resistant gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 65(11), 10–128 (2021).

Aher, T., Roy, A. & Kumar, P. Molecular detection of virulence genes associated with pathogenicity of Klebsiella spp. isolated from the respiratory tract of apparently healthy as well as sick goats. Isr. J. Vet. Med. 67(4), 249–252 (2012).

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, CLSI supplement M100-Ed34. (2024).

Alizadeh, R., Alipour, M. & Rezaee, F. Prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in health care centers in Mazandaran province. Avicenna J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8(4), 130–134 (2021).

Bakthavatchalam, Y. D., Walia, K. & Veeraraghavan, B. Susceptibility testing for aztreonam plus ceftazidime/avibactam combination: A general guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories in India. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 40(1), 3–6 (2022).

BaSkaran, V., JeyaMani, L., ThangaraJu, D., Sivaraj, R. & Jayarajan, J. Detection of carbapenemase production by modified carbapenem inactivation method among carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli at a tertiary care center in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. Natl. J. Lab. Med. 12, 11–14 (2023).

Ali, S. E., Mahmoud, N. A., Elamin, M. M., Amr, G. E. & Mahrous, H. K. Assessment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in intensive care unit of Zagazig University Hospitals. Microbes Infect. Dis. 5(1), 282–294 (2024).

Gandor, N. H., Amr, G. E., Eldin Algammal, S. M. & Ahmed, A. A. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant k. pneumoniae isolated from intensive care units of Zagazig University Hospitals. Antibiotics 11(8), 1108 (2022).

Moemen, D. & Masallat, D. T. Prevalence and characterization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from intensive care units of Mansoura University hospitals. Egypt. J. of Basic Appl. Sci. 4(1), 37–41 (2017).

El-Sweify MA, Gomaa NI, El-Maraghy NN, Mohamed HA. Phenotypic detection of carbapenem resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae in Suez Canal University Hospitals, Ismailiyah, Egypt. 4(2): 10-18. (2015).

Anani HA, El Madbouly AA, Althoqapy AA, El-Dydamoni OA. Al-Azhar University Journal for Virus Research and Studies. 3(1): 1-12. (2021).

Ashour, H. M. & El-Sharif, A. Species distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative aerobic bacteria in hospitalized cancer patients. J. Transl. Med. 7, 1–3 (2009).

Bratu, S. et al. Rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in New York City: a new threat to our antibiotic armamentarium. Arch. Intern. Med. 165(12), 1430–1435 (2005).

Giakkoupi, P. et al. Emerging Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates coproducing KPC-2 and VIM-1 carbapenemases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53(9), 4048–4050 (2009).

Marquez, P., Terashita, D., Dassey, D. & Mascola, L. Population-based incidence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae along the continuum of care, Los Angeles County. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34(2), 144–150 (2013).

Aboulela, A. G., Jabbar, M. F., Hammouda, A. & Ashour, M. S. Assessment of phenotypic testing by mCIM with eCIM for determination of the type of carbapenemase produced by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Egypt. J. Med. Microbiol. 32(1), 37–46 (2023).

Verma, G. et al. Modified carbapenem inactivation method and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-carbapenem inactivation method for detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cureus 16(6), e63340 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Carbapenem-resistant hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates from a tertiary hospital in China: Antimicrobial susceptibility, resistance phenotype, epidemiological characteristics, microbial virulence, and risk factors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1083009 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. Molecular characteristics and antimicrobial resistance profiles of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates at a tertiary hospital in Nanning, China. BMC Microbiol. 23(1), 318 (2023).

Tsai, Y. M., Wang, S., Chiu, H. C., Kao, C. Y. & Wen, L. L. Combination of modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and EDTA-CIM (eCIM) for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. BMC Microbiol. 20, 1–7 (2020).

Tamma, P. D. & Simner, P. J. Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms from clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56(11), 10–128 (2018).

Hammoudi Halat, D. & Ayoub, M. C. The current burden of carbapenemases: review of significant properties and dissemination among gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 9(4), 186 (2020).

Jia, X. et al. Coexistence of bla NDM-1 and bla IMP-4 in one novel hybrid plasmid confers transferable carbapenem resistance in an ST20-K28 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 13, 891807 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. First report in China of Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates harboring bla NDM-1 and bla IMP-4 drug resistance genes. Microb. Drug Resist. 21(2), 167–170 (2015).

Liu, L., Feng, Y., Long, H., McNally, A. & Zong, Z. Sequence type 273 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying bla NDM-1 and bla IMP-4. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62(6), 10–128 (2018).

Amer, R., Ateya, R. M., Arafa, M. & Yahia, S. H. Ceftazidime/avibactam efficiency tested in vitro against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from neonates with sepsis. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2, 529–540 (2021).

El-Domany, R. A., El-Banna, T., Sonbol, F. & Abu-Sayedahmed, S. H. Co-existence of NDM-1 and OXA-48 genes in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in Kafrelsheikh, Egypt. Afr. Health Sci. 21(2), 489–496 (2021).

Shawky, A. M., Tolba, S. & Hamouda, H. M. Emergence of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase blaNDM-1 and oxacillinases blaOXA-48 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Egyptian hospital. Egypt. J. Microbiol. 54(1), 25–37 (2019).

Okoche, D., Asiimwe, B. B., Katabazi, F. A., Kato, L. & Najjuka, C. F. Prevalence and characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from Mulago National Referral Hospital, Uganda. PloS One 10(8), e0135745 (2015).

Wang, Q. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: data from a longitudinal large-scale CRE study in Chin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67(2), S196-205 (2018).

Kilic, A. et al. Identification and characterization of OXA-48-producing, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Turkey. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 41(2), 161–166 (2011).

Baran, I. & Aksu, N. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a tertiary-level reference hospital in Turkey. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 15, 1–1 (2016).

Zowawi, H. M. et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the countries of the Gulf cooperation council: dominance of OXA-48 and NDM producers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58(6), 3085–3090 (2014).

Memish, Z. A. et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase production among gram-negative bacteria in Saudi Arabia. Microb. Drug Resist. 21(3), 307–314 (2015).

Li, Y., Shen, H., Zhu, C. & Yu, Y. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections among ICU admission patients in Central China: prevalence and prediction model. BioMed. Res. Int. 2019(1), 9767313 (2019).

Vardakas, K. Z. et al. Characteristics, risk factors and outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the intensive care unit. J. Infect. 70(6), 592–599 (2015).

Pierce, V. M. et al. Modified carbapenem inactivation method for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase production among Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55(8), 2321–2333 (2017).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan drug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18(3), 268–281 (2012).

Schwaber, M. J. & Carmeli, Y. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a potential threat. JAMA 300(24), 2911–2913 (2008).

Lee, N. Y. et al. Clinical impact of cefepime breakpoint in patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 57(2), 106250 (2021).

Coppi, M. et al. Multicenter evaluation of the RAPIDEC® CARBA NP test for rapid screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and gram-negative nonfermenters from clinical specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 88(3), 207–213 (2017).

Khan, S. et al. Evaluation of a simple method for testing aztreonam and ceftazidime-avibactam synergy in New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales. Plos One 19(5), e0303753 (2024).

Sreenivasan, P. et al. In-vitro susceptibility testing methods for the combination of ceftazidime-avibactam with aztreonam in metallo-beta-lactamase producing organisms: Role of combination drugs in antibiotic resistance era. J. Antibiot. 75(8), 454–462 (2022).

Wenzler, E., Deraedt, M. F., Harrington, A. T. & Danizger, L. H. Synergistic activity of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam against serine and metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative pathogens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 88(4), 352–354 (2017).

Pragasam, A. K. et al. Will ceftazidime/avibactam plus aztreonam be effective for NDM and OXA-48-Like producing organisms: Lessons learned from In vitro study. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 37(1), 34–41 (2019).

Rawson, T. M. et al. A practical laboratory method to determine ceftazidime-avibactam-aztreonam synergy in patients with New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM)–producing Enterobacterales infection. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 29, 558–562 (2022).

Taha, R., Kader, O., Shawky, S. & Rezk, S. Ceftazidime-avibactam plus aztreonam synergistic combination tested against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales characterized phenotypically and genotypically: a glimmer of hope. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 22(1), 2–10 (2023).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Khattab: concept and design of the study, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpreted the results, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. A. M. Askar: concept and design of the study, data acquisition, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. H. Abdellatif: concept and design of the study, data acquisition, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. A.A.A. Othman: concept and design of the study, interpreted the results, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. A. H. Rayan: concept and design of the study, interpreted the results, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. H. Azab: concept and design of the study, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpreted the results, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human ethics and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt, #5060. The patients provided informed consent, which addressed all the steps of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. The minor patient’s informed consent was obtained from a parent, which addressed all the steps of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. It is declared that: All methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations. It was performed according to the recommendations of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khattab, S., Askar, A.M., Abdellatif, H.A.A. et al. Synergistic combination of ceftazidime and avibactam with Aztreonam against MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICU patients. Sci Rep 15, 5102 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88965-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88965-7