Abstract

The relationship between lifestyle choices and health outcomes has received significant scholarly attention. Research indicates that factors such as obesity, insufficient physical activity, tobacco use, and poor dietary habits may elevate the odds of developing metabolic disorders. This study aimed to investigate the association between the combined healthy lifestyle score (HLS) and the odds of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its associated components in a population of apparently healthy adults. This cross-sectional study utilized data from the Dena PERSIAN cohort, which comprised 2,971 healthy adults. Participants’ combined HLS were evaluated using validated questionnaires that assessed body mass index (BMI), physical activity level (PAL), smoking status, and dietary quality. The evaluation of dietary nutritional quality was conducted using the most recent version of the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), known as HEI-2020. The combined HLS was measured on a scale ranging from zero, indicating an unhealthy lifestyle, to four, representing the healthiest lifestyle. Individuals with the highest combined HLS score had 81% lower odds of having MetS compared to those with the lowest score (OR: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.11–0.33). Higher combined HLS scores were significantly associated with decreased odds of abdominal adiposity (OR: 0.11; 95% CI: 0.07–0.18), abnormal glucose homeostasis (OR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35–0.86), elevated serum triglycerides (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.26–0.67), and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.24–0.65) after adjusting for sex, age, education level, and marital status (P < 0.05). The findings indicated a significant association between adherence to a combined HLS and a decreased odds of developing MetS and its associated components among Iranian adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of interrelated metabolic abnormalities, including abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, that frequently coexist, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO)1. MetS has emerged as a major public health concern. Previous studies indicate that this condition is associated with a twofold increase in the risk of coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, a fivefold increase in the risk of diabetes, and a 1.5-fold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality2. Although various diagnostic definitions exist for this syndrome, leading to differing estimates, the global prevalence of this disorder is reported to range between 12.5 and 31.4%3. Meta-analyses have estimated the prevalence of MetS in Iran to be between 20 and 30%4,5. Furthermore, the total cost of MetS, which includes healthcare expenses and the loss of potential economic productivity, amounts to billions of dollars6. Both its prevalence and associated costs are projected to increase in the future.

The pathophysiology of MetS is not yet fully understood; however, it is evident that this syndrome arises from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors7. Previous studies have identified both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors associated with this condition. Unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking are recognized as the primary modifiable risk factors that individuals can change to reduce their risk of developing MetS7,8,9,10,11,12. These factors are major components of an individual’s lifestyle. It is important to note that previous studies indicate a correlation among these lifestyle risk factors13,14,15,16. Therefore, to effectively prevent MetS, it is essential to consider a comprehensive set of lifestyle components, referred to as the Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS), rather than focusing solely on individual factors17.

Recent studies have investigated the combined effects of lifestyle factors—including healthy dietary patterns, regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding smoking—on the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and overall mortality. The findings from these studies suggest that greater adherence to a healthy lifestyle is associated with a reduced risk of complications18,19,20,21. Niu et al. conducted a recent cohort study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and found that a middle-weighted HLS was associated with a lower risk of mortality from all causes compared to a low score. A high score for a healthy lifestyle was also linked to a lower risk among individuals displaying characteristics of MetS22. In Iranian populations, Mirmiran et al. (2021) found that greater adherence to a healthy lifestyle was associated with a reduced risk of developing MetS over a six-year period in Tehran23. Additionally, Vajdi et al. demonstrated that lower adherence to a healthy lifestyle was associated with higher odds of MetS in women in Tabriz, even after adjusting for all covariates24. However, these studies have significant limitations. Mirmiran et al.'s study only examined the association between HLS and MetS without analyzing its components separately for men and women23. Additionally, Vajdi et al.'s study was constrained by a relatively small sample size (n = 347) and a narrow age range (20–50 years)24. Furthermore, both studies focused exclusively on urban populations, neglecting the potentially different lifestyle patterns in rural areas23,24. Therefore, a large-scale study that incorporates both urban and rural populations, analyzes individual components of MetS, and represents distinct geographical and ethnic groups is necessary to gain a better understanding of this relationship within the Iranian population. Given the limited information regarding the relationship between combined HLS and the odds of MetS and its components in adults, this study aims to assess the association between combined HLS and the odds of MetS and its components within a large population (n = 2971) that encompasses nearly the entire eligible adult demographic, both urban and rural, of the Dena region. This analysis utilizes data from the Dena PERSIAN Cohort Study in Iran.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

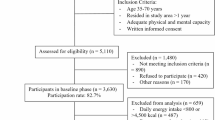

This cross-sectional study was conducted on a large population of adults using baseline phase data from the Dena PERSIAN cohort25,26. The Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (PERSIAN) Cohort (http://persiancohort.com) is a large longitudinal study focused on non-communicable diseases, encompassing various geographical, ethnic, and climatic groups across 18 provinces of Iran25. The Dena cohort includes nearly all individuals aged 35 to 70 years residing in both urban and rural areas of Dena County, which is located near Yasuj city in the Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province in southwestern Iran26.

Baseline phase data were collected from February 2018 to March 2020. The inclusion criteria comprised men and women aged 35 to 70 years, with a minimum duration of residence in the study area of over one year, sufficient physical and mental capacity to participate in the evaluation program, and the signing of a written consent form. The exclusion criteria included the inability to attend the clinic for a physical examination, intellectual disabilities, alcohol consumption, and unwillingness to participate in the study. Ultimately, 2971 subjects were included in the baseline phase of the study and subsequent analysis. More detailed information regarding the study design, participants, and data collection methods has been published previously26. Participants who reported a daily energy intake below 800 kcal or above 4500 kcal were excluded from the study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods and procedures conducted in this study adhered to the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. The objectives of the study were explained in detail, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants26. The study received approval from the ethics committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.YUMS.REC.1401.175).

Demographic, anthropometric, medical, and lifestyle assessment

The data, which included demographic, anthropometric, medical, and lifestyle measurements, were collected according to the cohort protocol by trained interviewers25,26. Anthropometric indicators, such as weight, height, and waist circumference (WC), were measured on the same day for each participant by trained healthcare providers at a health center. Height was measured using a stadiometer (Seca 755 1,021,994, Germany), ensuring that participants stood against a wall with their heels and buttocks in contact. Weight was measured using a calibrated standing scale (Seca 755 1,021,994, Germany), with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes to ensure accurate measurements. WC was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a flexible metric measuring tape (Seca 755 1,021,994, Germany). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters26.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice—first after a 5-min rest in a sitting position and again 15 min later, following the protocols for the right arm—using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (Richter, MTM Munich, Germany)26. Subjects were classified as smokers if they had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime27. Tobacco use was defined as the consumption of tobacco in the form of Naas, hookah, pipe, or snuff at least once a week for a minimum of six months26.

Assessment of physical activity level

The physical activity levels (PAL) of participants were evaluated using an Iranian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)28. The translation and validation of this questionnaire were previously conducted on the adult population of Iran, where all participants were asked to report their activities according to the questionnaire. Subsequently, the results of the IPAQ were expressed in terms of Metabolic Equivalent-hours per week (MET-h/week), considering the type, duration, and frequency of activities performed each week. Participants were then classified into quartiles based on their MET-h/week values: active, moderately active, moderately inactive, and inactive. We defined the low-risk group as individuals categorized as active and moderately active.

Dietary assessment

The dietary intakes of participants were assessed using a validated 113-item Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and a 127-item FFQ specifically designed for indigenous foods29,30. Participants were asked to report the frequency and portion sizes of food items consumed on a daily, weekly, monthly, and annual basis over the past year. All portion sizes and household sizes were converted to grams per day, and the energy and nutrient content of the foods were calculated using Nutritionist IV software (First Databank, San Bruno, CA).

Healthy eating index‑2020

The evaluation of dietary nutritional quality is conducted using the most recent version of the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), known as HEI-202031,32,33. The HEI is a measure developed by the USDA and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) that aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA)32. The HEI-2020 comprises 13 components, which are categorized into two groups: adequacy (9 ingredients) and moderation (4 ingredients). Adequacy components assess the consumption of foods that promote health, with higher scores indicating greater intake. These components include total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein foods, seafood, and plant proteins and fatty acids. Conversely, moderation components assess the intake of foods that should be limited, with higher scores reflecting lower intake. These components include saturated fats, refined grains, sodium, and added sugars. The HEI-2020 assigns scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better diet quality. The highest and lowest consumption levels of three adequacy components—dairy, whole grains, and fatty acids—were assigned scores of 10 and 0, respectively. The other six adequacy components—total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, total protein foods, seafood, and plant proteins—received scores of 0 for the lowest intake and 5 for the highest intake. Lastly, the highest and lowest consumption levels of moderation components—saturated fats, refined grains, sodium, and added sugars—were scored at 0 and 10, respectively. A key feature of the HEI is that its scoring system differentiates dietary quality from quantity through a method known as the density approach. The components are typically calculated as the amount of each food group per 1,000 cal in the overall dietary intake. The fatty acids component is an exception; it is scored based on the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids. To determine the total score of the HEI-2020, we summed the scores of the individual items, resulting in a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 10033. Individuals who ranked in the upper two-fifths of the HEI-2020 were considered to have a healthy diet.

Calculation of combined healthy lifestyle score (HLS)

The HEI-2020 score, PAL, BMI, and smoking status of participants were considered in the calculation of the combined HLS. Individuals received a score of zero or one for each of these four lifestyle components. A score of 1 was assigned for the presence of each of the following criteria: BMI < 25 kg/m2, being physically active or moderately active (highest and second-highest quartiles of MET-hours per week), being a non-smoking, and being in the upper two quintiles of the HEI-2020. Otherwise, they received a score of 0. The final combined HLS was calculated by summing the scores that each participant received for these four lifestyle components. A score of 4 indicates the highest adherence to a combined healthy lifestyle, while a score of 0 indicates the least adherence (Table 1)34.

Biochemical measurements

A 25 mL blood sample was collected in tubes containing either a clot activator or an anticoagulant, specifically one 7 mL clot tube and three 6 mL EDTA tubes, after an overnight fast. This was done to measure various biochemical variables, including fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides (TG). Following standard laboratory protocols and utilizing Pars Azmoon kits (Pars Azmoon Co, Tehran, Iran), all measurements were performed using a biochemistry autoanalyzer (BT1500, 47,173,738, Italy) and a hematology cell counter (Sysmex, XP B0463, Japan)26.

Definition of the metabolic syndrome

In this study, we defined metabolic syndrome based on the criteria established by the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III). The diagnosis of MetS requires the presence of three or more of the following components: (i) abdominal adiposity (WC > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women), (ii) elevated blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mm Hg or the use of antihypertensive medication), (iii) abnormal glucose homeostasis (FBG ≥ 100 mg/dL or the use of antidiabetic medication), (iv) low serum levels of HDL-C (< 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women), and (v) high serum TG levels (≥ 150 mg/dL or the use of fibrate medication)35.

Statistical analyses

In the current study, we performed all statistical analyses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We categorized all subjects into four groups based on the combined HLS scores (ranging from 0 to 4), with the first group (individuals scoring 0) serving as the reference group. Percentages were used to describe qualitative variables, while means ± standard deviation (SD) were employed to report quantitative variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess the normal distribution of the data.

To evaluate the differences among categories of combined HLS, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for continuous variables. Additionally, the Chi-square test was utilized to compare the distribution of individuals concerning categorical variables across the combined HLS categories. The association between combined HLS with MetS was investigated using binary logistic regression in both crude and multivariable-adjusted models. In the adjusted model, we adjusted for sex (male/female), age (continuous), education level (illiterate/elementary/diploma/university), and marital status (married/single/divorced/widowed).

Results

Based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 2,971 individuals were selected for this study, with an average age of 50.1 ± 9.7 years. The overall prevalence of MetS in our study population was 33.1%. The study population consisted of 62.9% urban and 37.1% rural residents, with a significant difference in HLS distribution between these areas (P = 0.005).

Table 2 presents a summary of the characteristics of the study participants categorized by their combined HLS into five groups (scores 0–4). The results indicate that participants in the highest combined HLS group were more physically active, better educated, and more likely to be married. Additionally, they were all non-smokers and exhibited lower BMI, weight, and rates of obesity compared to those in the lowest combined HLS group (P < 0.05). In addition, as indicated by the data in Table 2, participants with the highest combined HLS exhibited significantly lower serum levels of FBG and TG, as well as higher levels of HDL-C, compared to those with the lowest combined HLS (P < 0.05).

Table 3 presents the distribution of MetS and its components according to the combined HLS score categories. The overall prevalence of MetS components in our study population was as follows: abdominal adiposity (59.4%), elevated blood pressure (19.9%), abnormal glucose homeostasis (53.4%), low HDL-cholesterol (36.8%), and high serum triglycerides (39.5%). The distribution of MetS and its components, with the exception of elevated blood pressure, significantly decreased as the HLS score increased (P < 0.05).

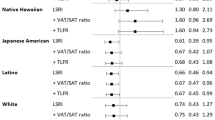

The OR and 95% CI for the presence of MetS and its components across the combined HLS score categories in both crude and adjusted models are presented in Table 4. In the crude model, individuals in the highest score of combined HLS had lower odds of having MetS and all its components except elevated blood pressure compared to those in the lowest score of combined HLS. These associations remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders including sex, age, education level, and marital status (Adjusted model).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the relationship between combined HLS and the odds of developing MetS and its components among the entire eligible adult population—both urban and rural—of the Dena region in Iran. Our findings indicate that the prevalence of MetS in our study population was 33.1%, and its components, with the exception of elevated blood pressure, significantly decreased as adherence to combined healthy lifestyle practices increased. These results suggest that combined HLS is negatively associated with the odds of MetS in the Iranian population, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Regarding the components of MetS, we observed that in both the crude and adjusted models, combined HLS was inversely associated with the odds of MetS components, except for elevated blood pressure. However, after incorporating BMI into the previously adjusted model, the odds of hypertriglyceridemia, abnormal glucose homeostasis, and low serum HDL-C remained significantly associated with combined HLS.

Our study is significant due to the high prevalence of MetS worldwide, its financial burden, and its association with CVD and diabetes2,4,5,6,36. In contrast to our research, a substantial body of literature has previously explored the relationship between lifestyle factors and the risk of MetS, often focusing on specific components such as PAL, smoking, and dietary habits. However, given that lifestyle factors are generally interconnected in typical living conditions, it is more advantageous to adopt a holistic approach that treats lifestyle as a singular composite variable. Our findings regarding the protective effects of combined healthy lifestyle factors against metabolic disorders align with previous studies. Clinical trials have demonstrated that diets rich in functional foods can significantly improve cardiovascular risk factors and inflammatory markers in overweight individuals37. Additionally, research has shown that adherence to healthy dietary patterns, which include whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, is associated with lower levels of inflammatory biomarkers. This association may help elucidate the protective effects of a healthy lifestyle against metabolic disorders38. Furthermore, long-term population-based studies suggest that dietary choices and lifestyle factors play a crucial role in metabolic health by modulating inflammatory pathways39.

Recently, several studies have investigated the combined effects of HLS on coronary disease21, mortality18, and MetS23,24. Research conducted in North America and Spain has demonstrated that healthy lifestyle habits significantly reduce the odds of developing MetS40,41. A cross-sectional study involving 787 individuals aged 45 to 75 found that HLS, defined as a composite measure of diet, smoking, PAL, and alcohol consumption, was associated with a decreased odds of MetS42. Van Wormer et al.43 found that over a two-year period, reducing healthy lifestyle factors such as weight, alcohol consumption, and fruit and vegetable intake increases the risk of developing MetS. Furthermore, our findings regarding MetS are further supported by recent studies that have examined the relationship between HLS and the risk of MetS in healthy adults23,24. In 2021, a cohort study conducted in Iran by Mirmiran et al. found that a higher score of HLS was associated with a reduced risk of developing MetS over a six-year period, independent of confounding factors23. The researchers evaluated the HLS using three components: the Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HLS-AHEI-2010), the modified French Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score, and the Healthy Diet Pattern Score (HLS-HDP). They believe that the method proposed by Patel et al.18, is more appropriate for assessing HLS and their relationship with the risk of MetS in the Iranian population. This method utilizes the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) 2010 to evaluate dietary quality, which is a well-established index that has demonstrated an inverse relationship with the risk of cardiometabolic disorders across various populations. It is important to note that we utilized the HEI-2020, the updated version of the AHEI-2010, in our study. Another investigation conducted in the United States found no association between alcohol consumption, PAL, smoking, and MetS44. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in study designs, sample sizes, diagnostic criteria for MetS, fundamental characteristics such as age and sex, diverse methodologies for assessing HLS, and inadequate adjustments for confounding factors.

Concerning the components of MetS, the combined HLS exhibited an inverse relationship with impaired glucose homeostasis, reduced serum levels of HDL-C, and elevated TG levels, even after adjusting for potential confounding factors. Consistent with our findings, Vajdi et al. demonstrated that higher levels of combined HLS were inversely associated with the odds of abnormal glucose homeostasis and elevated TG levels24. Furthermore, Farhadnejad et al. found that individuals in the highest quartile of HLS exhibited lower levels of FBG, TG, LDL-C, and blood pressure (BP), as well as higher levels of HDL-C20. Additionally, a study conducted by El Bilbeisi et al. indicated that among diabetic patients, those in the lowest quartile of HEI-2010 showed an increased odds of developing MetS45. A significant factor of combined HLS that influences the risk of MetS is the dietary quality of the participants, as measured by the HEI. Our research indicated that a higher combined HLS is associated with reduced consumption of added sugars, increased intake of vegetables, and decreased consumption of meats. Previous studies, such as those conducted by Jowshan et al., found that the scores of HEI-2015 components (total vegetables and added sugars) were linked to a lower odds of developing MetS46. Additionally, the Bogalusa Heart Study highlighted an association between low intake of fruits and vegetables and the prevalence of MetS47. The proposed mechanisms to explain this relationship can be attributed to the high levels of phytochemicals and antioxidants present in fruits and vegetables. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of these compounds can help reduce inflammation in the body, lower insulin resistance, and protect cellular health35,48. Consequently, research has demonstrated that dietary patterns rich in fruits and vegetables improve the components of metabolic syndrome49,50.

PAL is a key variable in the calculation of the combined HLS in our research, as well as in other comparable studies23,24. The existing literature suggests that PAL may provide a protective effect against the risk of MetS, as indicated by a meta-analysis of cohort studies51. This protective mechanism has been associated with a reduction in central adiposity by inducing a negative energy balance. Additionally, it positively influences glucose metabolism by upregulating insulin receptors in muscle tissue, thereby enhancing insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, physical activity promotes beneficial changes in lipid deposition patterns, increases plasma antioxidant capacity, and elevates levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines51,52,53,54. Our study underscores the significance of PAL, aligning with the findings of Mirmiran et al., which indicate that an increase in PAL is associated with a significant rise in combined HLS23.

A critical component of lifestyle that influences the risk of MetS is the assessment of dietary quality among participants. As previously mentioned, the HEI-2020 represents the most recent iteration of this index, following the HEI-2015, which was an updated version of the HEI-201031,32,33. Although numerous studies have used this tool to assess dietary quality concerning conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, smoking status, cancer survival, aging, and chronic renal failure55,56,57,58,59, to our knowledge, this is the first study to employ the HEI-2020 to assess dietary quality and its association with MetS in healthy adults. Two studies have indicated that higher adherence to the HEI-2010 is associated with a reduced risk of MetS among adult women60 and patients with type 2 diabetes61. Furthermore, greater adherence to healthy dietary patterns that are rich in whole grains, fiber, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes, while being low in red and processed meats, is associated with decreased inflammatory markers and a lower risk of MetS49,50,62,63.

Obesity is a primary underlying risk factor for MetS due to its role in elevating inflammatory markers, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance64,65. Our study demonstrated a significant adverse association between combined HLS and abdominal obesity, even after adjusting for sex, age, physical activity, cigarette smoking, education level, and marital status. However, this association became non-significant after further adjustment for BMI. Therefore, we can cautiously conclude that the major impact of BMI on MetS is primarily attributed to abdominal obesity and fat distribution.

The present study has several limitations. First, although validated questionnaires were employed to assess dietary habits and physical activity, some measurement errors are unavoidable. Second, the consumption of alcoholic beverages, such as wine and liquor, is uncommon among the Iranian population due to religious considerations. Additionally, while we adjusted for major confounding variables in our models, there may still be residual or unmeasured confounders, the effects of which cannot be disregarded. Fourth, consistent with the characteristics of most cross-sectional designs, it is important to interpret these findings with the understanding that causality and directionality of the associations cannot be established. The current research has several strengths, including its dynamic participation that encompasses both rural and urban populations within the region, a prospective design, an appropriate age range for participants, and a relatively substantial sample size. Additionally, our study comprehensively assessed lifestyle factors by incorporating smoking status along with dietary quality, physical activity, and BMI in the combined HLS calculation. Furthermore, this study assessed diet quality using the HEI-2020 rather than relying solely on individual dietary components. Additionally, we employed validated and reliable food frequency and physical activity questionnaires to collect data on dietary intake and levels of physical activity.

Conclusion

The results of our cross-sectional study indicated a significant association between higher combined HLS and reduced odds of MetS and its components in Iranian adults. Further longitudinal and intervention studies in the general population should be conducted to confirm these relationships.

Data availability

On reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide the datasets used and analyzed during the current work.

Abbreviations

- HLS:

-

Healthy lifestyle score

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HEI-2020:

-

Healthy eating index-2020)

- PERSIAN:

-

Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran

- WC:

-

Waist circumferences

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- IPAQ:

-

International physical activity questionnaires

- MET-h/day:

-

Metabolic equivalents-hours per day

- FFQ:

-

Frequency questionnaire

- DGA:

-

Dietary guidelines for Americans

References

Consultation W. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part; 1999.

Engin A. The definition and prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. In Obesity and lipotoxicity. pp.1–17 (2017).

Noubiap, J. J. et al. Geographic distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components in the general adult population: A meta-analysis of global data from 28 million individuals. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 188, 109924 (2022).

Mazloomzadeh, S., Khazaghi, Z. R. & Mousavinasab, N. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis Iran. J. Public Health 47(4), 473 (2018).

Farmanfarma, K. K. et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iran: A meta-analysis of 69 studies. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 13(1), 792–799 (2019).

Sullivan, P. W., Ghushchyan, V., Wyatt, H. R. & Hill, J. O. The medical cost of cardiometabolic risk factor clusters in the United States. Obesity. 15(12), 3150–3158 (2007).

Bovolini, A., Garcia, J., Andrade, M. A. & Duarte, J. A. Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology and predisposing factors. Int. J. Sports Med. 42(03), 199–214 (2021).

Gennuso, K. P., Gangnon, R. E., Thraen-Borowski, K. M. & Colbert, L. H. Dose–response relationships between sedentary behaviour and the metabolic syndrome and its components. Diabetologia. 58, 485–492 (2015).

Kwon, H., Kim, D. & Kim, J. S. Body fat distribution and the risk of incident metabolic syndrome: A longitudinal cohort study. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 10955 (2017).

Yang, C. S., Zhang, J., Zhang, L., Huang, J. & Wang, Y. Mechanisms of body weight reduction and metabolic syndrome alleviation by tea. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 60(1), 160–174 (2016).

Park, Y.-W. et al. The metabolic syndrome: Prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch. Intern. Med. 163(4), 427–436 (2003).

Shin, H. S., Oh, J. E. & Cho, Y. J. The association between smoking cessation period and metabolic syndrome in Korean men. Asia Pacific J. Public Health. 30(5), 415–424 (2018).

Vajdi, M., Nikniaz, L., Pour Asl, A. M. & Abbasalizad, F. M. Lifestyle patterns and their nutritional, socio-demographic and psychological determinants in a community-based study: A mixed approach of latent class and factor analyses. PLoS One. 15(7), e0236242 (2020).

Golubić, M. et al. Comprehensive lifestyle modification intervention to improve chronic disease risk factors and quality of life in cancer survivors. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 24(11), 1085–1091 (2018).

Steyn, K. & Damasceno, A. Lifestyle and related risk factors for chronic diseases. Disease Mort. Sub-Saharan Africa. 2, 247–265 (2006).

Santos, L. The impact of nutrition and lifestyle modification on health. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 97, 18–25 (2022).

Garralda-Del-Villar, M. et al. Healthy lifestyle and incidence of metabolic syndrome in the SUN cohort. Nutrients. 11(1), 65 (2018).

Patel, Y. R., Gadiraju, T. V., Gaziano, J. M. & Djoussé, L. Adherence to healthy lifestyle factors and risk of death in men with diabetes mellitus: The Physicians’ Health Study. Clin. Nutr. 37(1), 139–143 (2018).

Noethlings, U., Ford, E. S., Kroeger, J. & Boeing, H. Lifestyle factors and mortality among adults with diabetes: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. J. Diabetes. 2(2), 112–117 (2010).

Farhadnejad, H. et al. The higher adherence to a healthy lifestyle score is associated with a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in Iranian adults. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 22(1), 42 (2022).

Khera, A. V. et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(24), 2349–2358 (2016).

Niu, M. et al. Emerging healthy lifestyle factors and all-cause mortality among people with metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-like characteristics in NHANES. J. Transl. Med. 21(1), 239 (2023).

Mirmiran, P., Farhadnejad, H., Teymoori, F., Parastouei, K. & Azizi, F. The higher adherence to healthy lifestyle factors is associated with a decreased risk of metabolic syndrome in Iranian adults. Nutr. Bull. 47(1), 57–67 (2022).

Vajdi, M., Karimi, A., Farhangi, M. A. & Ardekani, A. M. The association between healthy lifestyle score and risk of metabolic syndrome in Iranian adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23(1), 16 (2023).

Poustchi, H. et al. Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): Rationale, objectives, and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187(4), 647–655 (2018).

Harooni, J. et al. Cohort profile: The PERSIAN Dena Cohort Study (PDCS) of non-communicable diseases in Southwest Iran. BMJ open. 14(4), e079697 (2024).

Control CfD, Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2004. MMWR. 2005; 54: 1121–1124. 2006.

Moghaddam, M. B. et al. The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: Content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl. Sci. J. 18(8), 1073–1080 (2012).

Eghtesad, S. et al. Validity and reproducibility of the PERSIAN Cohort food frequency questionnaire: Assessment of major dietary patterns. Nutr. J. 23(1), 35 (2024).

Eghtesad, S. et al. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire assessing food group intake in the PERSIAN Cohort Study. Front. Nutr. 10, 1059870 (2023).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 118(9), 1591–1602 (2018).

Phillips, J. A. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2020–2025. Workplace Health Saf. 69(8), 395 (2021).

Shams-White, M. M. et al. Healthy eating index-2020: review and update process to reflect the dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 123(9), 1280–1288 (2023).

Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S., Shayanfar, M., Mohammad-Shirazi, M., Sharifi, G. & Esmaillzadeh, A. A combined healthy lifestyle score in relation to glioma: a case-control study. Nutr. J. 21(1), 6 (2022).

Huang, P. L. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Disease Models Mech. 2(5–6), 231–237 (2009).

Obeidat, A. A., Ahmad, M. N., Haddad, F. H. & Azzeh, F. S. Alarming high prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Jordanian adults. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 31(6), 1377 (2015).

Izadi, V., Haghighatdoost, F., Moosavian, P. & Azadbakht, L. Effect of low-energy-dense diet rich in multiple functional foods on weight-loss maintenance, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 37(5), 399–405 (2018).

Arabzadegan, N. et al. Effects of dietary whole grain, fruit, and vegetables on weight and inflammatory biomarkers in overweight and obese women. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorexia Bulimia Obesity. 25, 1243–1251 (2020).

Hassannejad, R. et al. Long-term association of red meat consumption and lipid profile: A 13-year prospective population-based cohort study. Nutrition. 86, 111144 (2021).

Sotos-Prieto, M. et al. Association between the Mediterranean lifestyle, metabolic syndrome and mortality: a whole-country cohort in Spain. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 1–12 (2021).

Hershey, M. S. et al. The Mediterranean lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index and metabolic syndrome in a non-Mediterranean working population. Clin. Nutr. 40(5), 2494–2503 (2021).

Sotos-Prieto, M. et al. A healthy lifestyle score is associated with cardiometabolic and neuroendocrine risk factors among Puerto Rican adults. J. Nutr. 145(7), 1531–1540 (2015).

VanWormer, J. J., Boucher, J. L., Sidebottom, A. C., Sillah, A. & Knickelbine, T. Lifestyle changes and prevention of metabolic syndrome in the Heart of New Ulm Project. Prevent. Med. Rep. 6, 242–245 (2017).

Bhanushali, C. J. et al. Association between lifestyle factors and metabolic syndrome among African Americans in the United States. J. Nutr. Metabol. 2013(1), 516475 (2013).

El Bilbeisi, A. H., El Afifi, A. & Djafarian, K. Association of healthy eating index with metabolic syndrome and its components among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine: A cross sectional study. Integr. Food Nutr. Metab. https://doi.org/10.15761/IFNM.1000271 (2019).

Jowshan, M.-R. et al. Association between healthy eating index-2015 scores and metabolic syndrome among Iranian women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 24(1), 30 (2024).

Yoo, S. et al. Comparison of dietary intakes associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors in young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80(4), 841–848 (2004).

Feinkohl, I. et al. Associations of the metabolic syndrome and its components with cognitive impairment in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 19, 1–11 (2019).

Azadbakht, L., Mirmiran, P., Esmaillzadeh, A., Azizi, T. & Azizi, F. Beneficial effects of a dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 28(12), 2823–2831 (2005).

Esposito, K. et al. Effect of a mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: A randomized trial. Jama. 292(12), 1440–1446 (2004).

Zhang, D. et al. Leisure-time physical activity and incident metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Metabolism. 75, 36–44 (2017).

Gomez-Cabrera, M. C., Domenech, E. & Viña, J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: upregulation of antioxidant genes by training. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44(2), 126–131 (2008).

Hidalgo-Santamaria, M. et al. Exercise intensity and incidence of metabolic syndrome: The SUN project. Am. J. Prev. Med. 52(4), e95–e101 (2017).

DiMenna, F. J. & Arad, A. D. Exercise as “precision medicine” for insulin resistance and its progression to type 2 diabetes: a research review. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 10, 21 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. The combined effects of the most important dietary patterns on the incidence and prevalence of chronic renal failure: Results from the US national health and nutrition examination survey and mendelian analyses. Nutrients. 16(14), 2248 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Body mass index mediates the association between four dietary indices and phenotypic age acceleration in adults: a cross-sectional study. Food Funct. 15(15), 7828–7836 (2024).

Liu, J. C. et al. Association between pre- and post-diagnosis healthy eating index 2020 and ovarian cancer survival: evidence from a prospective cohort study. Food Funct. 15(16), 8408–8417 (2024).

Luo, T. & Tseng, T. S. Diet quality as assessed by the healthy eating index-2020 among different smoking status: an analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) data from 2005 to 2018. BMC Public Health. 24(1), 1212 (2024).

Zhiyi, L. et al. Association of the healthy dietary index 2020 and its components with chronic respiratory disease among U.S. adults. Front Nutr. 11, 1402635 (2024).

Saraf-Bank, S., Haghighatdoost, F., Esmaillzadeh, A., Larijani, B. & Azadbakht, L. Adherence to healthy eating index-2010 is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome and its features among Iranian adult women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 71(3), 425–430 (2017).

El Bilbeisi, A. H., Hosseini, S. & Djafarian, K. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome among Type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza strip Palestine. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 27(3), 227–238 (2017).

Saneei, P. et al. Adherence to the DASH diet and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Iranian women. Eur. J. Nutr. 54(3), 421–428 (2015).

Esposito, K., Kastorini, C. M., Panagiotakos, D. B. & Giugliano, D. Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome: an updated systematic review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 14(3), 255–263 (2013).

Grundy, S. M. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89(6), 2595–2600 (2004).

Okura, T. et al. Body mass index ≥23 is a risk factor for insulin resistance and diabetes in Japanese people: A brief report. PLoS One. 13(7), e0201052 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to everybody who took part in the study. This project was also supported by the research council of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Funding

This study was supported by Yasuj University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and Design: F.A, A.H.M, S.A., S.H.S Acquisition of Data: M.J. Analysis and Interpretation of Data: S.H.S, F.A, S.A. Drafting the Manuscript: A.P, M.Z, M.H, M.J. Revising Manuscript for Intellectual Content: M.J, S.A., F.A. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jowshan, MR., Pourjavid, A., Amirkhizi, F. et al. Adherence to combined healthy lifestyle and odds of metabolic syndrome in Iranian adults: the PERSIAN Dena cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 5164 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89028-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89028-7