Abstract

Ropivacaine for thoracoscopy-guided thoracic paravertebral block (TTPB) offers only a short duration of postoperative pain relief, which is inadequate for managing pain following thoracic surgery. Research has shown that combining dexamethasone with ropivacaine significantly prolongs the duration of analgesia from the nerve block. We hypothesised that TTPB with ropivacaine combined with dexamethasone would enhance postoperative analgesia and prolong the duration of analgesia in patients undergoing radical thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery. The study randomly assigned patients to either a control group (Group C, n = 40) or a dexamethasone group (Group D, n = 40). TTPB injection of ropivacaine or ropivacaine combined with dexamethasone prior to surgical sutures. The study compared postoperative pain satisfaction scores、48 h postoperative rescue analgesia frequency、visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, the 24-h patient-controlled analgesia (PCIA) sufentanil consumption, blood glucose levels, adverse events and recovery status. Group D demonstrated higher postoperative pain satisfaction scores and lower 48 h postoperative rescue analgesia frequency compared to Group C. Additionally, Group D had significantly lower VAS scores at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h post-operation, as well as a reduced 24-h PCIA sufentanil consumption, shorter time to first mobilization, and shorter hospital stay compared to Group C (all P < 0.05). The VAS scores at 2 h postoperatively were significantly lower in Group D compared to scores at 24 and 48 h postoperatively. Conversely, Group C showed significantly lower VAS scores at 2 h postoperatively compared to scores at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively. The addition of dexamethasone as an adjuvant to ropivacaine enhanced the analgesic efficacy of TTPB, prolonged the duration of pain relief, and reduced the time to first ambulation and hospital stay duration.

Trial Registry: ChiCTR (2400086347); Registered 28/06/2024.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer in China are among the highest for all malignant tumors1. Surgical intervention is the preferred treatment for early and mid-stage pulmonary tumors2. Thoracoscopic surgery, characterized by smaller incisions, substantially decreases surgical trauma3. However, perioperative pain and the stress response remain significant issues, contributing to increased postoperative complications, prolonged hospital stays, adverse effects on surgical outcomes and recovery, and heightened financial burdens on patients4.

Ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block (UTPB) is commonly used to provide postoperative analgesia in thoracic surgical procedures. It effectively reduces surgical stress and postoperative pain while avoiding the hypotension associated with thoracic epidural analgesia. However, UTPB requires proficiency in ultrasound-guided techniques and has a high failure rate, which limits its application in thoracic surgeries5. In contrast, thoracoscopic-guided thoracic paravertebral block (TTPB) involves injecting local anesthetics paravertebrally under direct visualization before chest closure. This method allows for clear visualization of the local anesthetic spread across 2–4 vertebral segments around the injection site6. It effectively alleviates postoperative pain in minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgeries such as radical lung cancer surgery, thereby promoting postoperative recovery7,8.

In clinical practice, the long-acting local anesthetic ropivacaine is commonly used for thoracic paravertebral block, but its analgesic effect typically lasts only about 6 h, which is insufficient for effective postoperative pain relief in thoracic surgeries9. Several studies have demonstrated that adding dexamethasone as an adjuvant to ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided blocks can significantly enhance and prolong the analgesic duration10,11.However, there has been a lack of published reports on the use of dexamethasone in combination with ropivacaine specifically for TTPB. Therefore, this study was aimed to compare the postoperative analgesic efficacy, duration of analgesia, postoperative rescue analgesia frequency, opioid consumption, pain satisfaction scores, incidence of adverse reactions, and postoperative recovery outcomes between ropivacaine alone and ropivacaine combined with dexamethasone for TTPB in thoracic surgeries.

Results

Baseline characteristics and surgical parameters

This study enrolled a total of 80 patients who were randomly assigned to Group C and Group D. During the course of the study, one patient in Group D required conversion from thoracoscopic to open surgery, and one patient in Group C experienced severe pleural adhesions during surgery. Consequently, these two patients were excluded from the final analysis. Thus, a total of 78 patients successfully completed both surgical and research procedures, as shown in the flow chart (Fig. 1). No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics and surgical parameters between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Primary outcomes

Frequency of rescue analgesia in the 48 h postoperative period was lower in group D compared to group C (1.4 ± 1.2 vs. 3.8 ± 1.6, t = 7.356, P < 0.001, Table 2). A comparison of postoperative pain satisfaction scores upon hospital discharge revealed a significantly higher level in Group D compared to Group C (8.4 ± 0.7 vs. 7.2 ± 0.8, t = − 7.287, P < 0.001, Table 2).

Secondary outcomes

The PCIA sufentanil consumption at 24 h postoperatively was significantly lower in Group D compared to Group C (43.9 ± 2.8 vs. 50.1 ± 2.7, t = 10.014, P < 0.001, Table 2). The VAS scores at 2 h postoperatively (both at rest and during coughing) were significantly lower in Group D compared to 24 and 48 h, whereas Group C showed significantly lower scores at 2 h compared to 6, 12, 24, and 48 h (Table 3). Additionally, VAS scores at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h (both at rest and during coughing) were significantly lower in Group D compared to Group C. There were no significant differences in VAS scores between the two groups at 2 h post-operation (Table 3). Group D showed a significant increase in blood glucose levels at 2 and 6 h postoperatively compared to Group C (Fig. 2). Furthermore, Group D had significantly shorter times to first ambulation and postoperative hospital stay compared to Group C. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of preoperative blood glucose levels, chest tube removal time, or incidence of adverse events (Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

As a minimally invasive procedure, thoracoscopic lobectomy offers benefits such as reduced surgical trauma and quicker recovery12. However, it can still lead to significant pain attributed to factors such as intercostal nerve injury, incisional discomfort, and the presence of chest tubes13,14. This pain can impede patients from deep breathing, coughing to clear sputum, and initiating early ambulation. Effective postoperative pain management is crucial as it promotes early active coughing, enhances lung function, reduces postoperative complications, and facilitates overall recovery4. Therefore, perioperative pain management should be prioritized. Effective postoperative analgesia not only accelerates patient recovery but also shortens hospital stays.

Thoracoscopic lobectomy commonly adopts paravertebral nerve block for postoperative analgesia, owing to its proven efficacy in clinical practice8. The thoracic paraspinal space is characterized by a triangular structure in the horizontal plane and houses various anatomical components, including spinal nerves within the intervertebral foramen, intercostal nerves, and the sympathetic chain15. Guided by thoracoscopy, paravertebral nerve block allows visualization of the local anesthetic spreading horizontally within the paravertebral space and vertically to adjacent paravertebral spaces. The analgesic effect of paravertebral nerve blockade is comparable to that of unilateral epidural blockade. Studies have demonstrated that TTPB effectively reduces postoperative pain in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy16. Consistent with findings from other researchers, TTPB is both effective and safe5.

Compared to UTPB, TTPB offers several advantages: it is simpler to perform, has a higher success rate, and reduces the risk of complications such as pneumothorax, accidental entry into the subarachnoid or epidural spaces17. However, the analgesic efficacy of a single dose of ropivacaine for TTPB is limited, which may not adequately meet the postoperative pain relief needs of patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy. To address this challenge, several studies have demonstrated that dexamethasone as an adjuvant combined with ropivacaine can enhance the analgesic intensity and prolong the duration of nerve blocks in ultrasound-guided procedures11,18,19. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of dexamethasone as an adjuvant in combination with ropivacaine versus ropivacaine alone for postoperative analgesia in TTPB. The goal was to identify an optimal analgesic approach and drug regimen that could enhance postoperative pain management, reduce the frequency of postoperative rescue analgesia, improve postoperative pain satisfaction, and promote recovery in patients.

In this study, patients in Group D exhibited significantly higher postoperative pain satisfaction scores and lower 48 h postoperative rescue analgesia frequency compared to Group C, indicating greater satisfaction with pain relief. Several factors contribute to this observed difference. Firstly, as a glucocorticoid, dexamethasone inhibits the production of cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and peripheral phospholipase, thereby reducing the synthesis of pain mediators such as prostaglandins and bradykinin. These inflammatory substances play a crucial role in pain transmission, and dexamethasone’s inhibitory effect also helps alleviate pain20. Secondly, dexamethasone enhances vascular responsiveness to catecholamines, leading to vasoconstriction. It slows the absorption of ropivacaine, prolonging its presence in local tissues and thereby extending the duration of analgesia19, which further contributes to pain relief. Therefore, when combined with ropivacaine, dexamethasone synergistically enhances the analgesic effect on paravertebral tissues, prolonging pain relief21,22. Group D also demonstrated reduced PCIA sufentanil consumption for 24 h postoperatively compared to Group C, underscoring the superior analgesic efficacy in Group D. This approach not only ensured effective pain management but also reduced perioperative opioid use, mitigating the potential for adverse reactions and opioid-related issues such as addiction23.

A review of the literature revealed that ropivacaine typically provided nerve blockade for approximately 6 h9. In this study, Group C exhibited significantly lower VAS scores at the 2-h mark (both at rest and during coughing) compared to scores at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h, indicating a significant increase in pain after 6 h. Conversely, Group D showed significantly lower VAS scores at 2 h (both at rest and during coughing) compared to 24 and 48 h, suggesting increased pain intensity after 24 h in the dexamethasone combined with ropivacaine group. Previous studies have demonstrated that combining dexamethasone with ropivacaine prolongs the duration of TTPB. Compared to Group C, Group D exhibited lower VAS scores at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h (both at rest and during coughing), indicating prolonged block duration and enhanced analgesic efficacy, consistent with other research findings11. Additionally, Group D demonstrated significantly shorter time to first mobilization and hospital stay compared to Group C, highlighting that effective TTPB facilitates early mobilization, independent coughing, and shorter hospital stays, thus promoting postoperative recovery7. Postoperative blood glucose levels at 2 and 6 h were higher in Group D compared to Group C, indicating dexamethasone-induced hyperglycemia. Dexamethasone, a long-acting glucocorticoid, elevates blood glucose levels by promoting gluconeogenesis, reducing glucose utilization, enhancing the effects of other glucose-elevating hormones, and accelerating protein breakdown21,24. Therefore, careful monitoring of blood glucose levels is essential when administering dexamethasone, particularly in diabetic patients. Caution should be exercised in using glucocorticoids in this population to mitigate the risk of hyperglycemia. The incidence of postoperative adverse reactions was low, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups, and neither group experienced epidural blockade, indicating the safety of TTPB.

There were several limitations to this study that warrant consideration in future research. The postoperative pain scores were assessed only at specific time points and revealed that the combination of dexamethasone and ropivacaine could extend the analgesic duration of TTPB from 12 to 24 h. However, we did not conduct a more detailed statistical analysis to precisely quantify this extension. Therefore, future studies should include more frequent assessments of pain at various time intervals to accurately determine the specific duration of TTPB analgesia with dexamethasone and ropivacaine. Additionally, exploring the absorption and retention kinetics of local anesthetics in the thoracic paravertebral space using imaging data could provide valuable insights into their correlation with the duration of analgesia. This approach will be pursued in our future research endeavors to further enhance our understanding of TTPB and optimize its clinical application.

Conclusion

Dexamethasone as an adjuvant with ropivacaine enhanced the analgesic potency of TTPB, prolonged the duration of pain relief, decreased the requirement for postoperative opioids and the frequency of rescue analgesia, improved pain satisfaction scores, shortened the time to initial mobilization and hospital stays, and promoted overall patient recovery. However, the combination of dexamethasone with ropivacaine may elevate postoperative blood glucose levels, necessitating caution when administering it to diabetic patients.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a single-center, prospective, triple-blind, randomized clinical trial. This study was adhered to the Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement25. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study enrolled a total of 80 patients who underwent thoracoscopic radical surgery for lung cancer at the hospital between July 2024 and September 2024.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients scheduled for elective thoracoscopic lobectomy, aged 20–75 years; (2) Patients classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Grade II; (3) The BMI ranges from 18 to 30 kg/m2; (4) Patients who consented to participate. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients allergic to ropivacaine or dexamethasone; (2) Patients with diabetes, coagulation abnormalities, thoracic spinal deformities, fractures, trauma, or a history of surgery affecting the thoracic spine; (3) Patients requiring conversion to open thoracotomy during surgery; (4) Patients with severe pleural adhesions. The surgical procedures and TTPB were performed by a team of experienced thoracic surgeons, and anesthesia was administered by experienced anesthetists.

Randomization and blinding

A computer-generated random number table in a 1:1 ratio created by an independent investigator was used for randomization and allocation. The allocation was numbered in sequence and sealed in light-tight envelopes by a dedicated nurse. This nurse was responsible for recording the group assignments and preparing the necessary medications for thoracic surgeons before TTPB. The paravertebral block under thoracoscopic guidance was performed by the surgeon. Neither the nurse, surgeon, nor anesthesiologist participated in follow-up, data assessment of study indicators, or data analysis. Postoperative follow-up and evaluation by anesthesiologists who did not participate in the surgery. Additionally, both the patients and other researchers such as data analysts were unaware of the group assignments, maintaining the study’s triple-blind nature.

Anesthesia procedure

During the surgical procedure, all patients underwent continuous monitoring of electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry (SpO2), end-tidal CO2 pressure (PETCO2), and bispectral index (BIS). Under local anesthesia, internal jugular vein cannulation and radial artery cannulation with pressure measurement were performed. Anesthesia induction was achieved using rapid total intravenous induction with the following drugs: midazolam (0.05 mg/kg), propofol (2 mg/kg), sufentanil (0.4 μg/kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). Following oral double-lumen endotracheal intubation, proper positioning was confirmed using a fiberoptic bronchoscope, and intermittent positive pressure ventilation was initiated. A tidal volume of 8 ml/kg was employed during double-lung ventilation, while a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg was used during single-lung ventilation, with a controlled respiratory rate of 10–14 breaths per minute. Throughout surgery, PETCO2 was maintained between 35 and 40 mmHg. Anesthesia maintenance included propofol infusion at a rate of 6–8 mg/(kg·h), remifentanil infusion at 0.1–0.3 μg/(kg·min), and rocuronium bromide administered intravenously as a single dose of 0.2 mg/(kg·0.5 h). Adjustments to anesthesia dosages were made intraoperatively to maintain the BIS value between 40 and 60, ensuring appropriate anesthesia depth.

Surgical procedure

Patients underwent a two-port thoracoscopic lobectomy. The surgical incisions were made in the seventh intercostal space along the midaxillary line and the fourth intercostal space between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line. Intraoperative pathology confirmed the presence of a malignant tumor, and thoracoscopic lobectomy was performed. Prior to closing the thoracic incisions, a No. 26 thoracic drainage tube was placed.

Analgesia methods

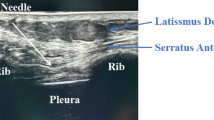

Before closing the thoracic incision, a No. 5 scalp needle, accompanied by an extension tube, was inserted into the paravertebral block site under thoracoscopic guidance. The needle was positioned 1 cm lateral to the T5-T6 vertebral interspace and advanced vertically to a depth of 0.5 cm below the parietal pleura (Fig. 3). After confirming the absence of blood or cerebrospinal fluid return upon aspiration, Group C received a 20 ml injection of 0.375% ropivacaine. Group D received a 20 ml injection of a solution diluted with 0.1 mg/kg of dexamethasone combined with 0.375% ropivacaine26. Following a 5-min observation period to ensure no bleeding or hematoma formation. A patient-controlled intravenous analgesia pump (PCIA) was connected after the surgical procedure concluded. The PCIA contained a solution of sufentanil (1.5 µg/kg) and tropisetron (5 mg), diluted with 0.9% sodium chloride injection to a total volume of 100 ml. The PCIA settings were as follows: a loading dose of 2 ml, a background infusion rate of 2 ml/h, a bolus dose of 0.5 ml, and a lockout interval of 15 min. When the VAS score reached ≥ 5 or the patient’s pain remains unacceptable after PCIA compression, rescue analgesia was administered in the form of 50 mg of flurbiprofen axetil.

Data collection

The primary outcomes measured in this study were the frequency of 48 h postoperative rescue analgesia and postoperative pain satisfaction scores upon hospital discharge, postoperative pain satisfaction scores were rated on a scale from 0 to 10. A score of 0 indicated the lowest level of satisfaction, while a score of 10 indicated the highest level of satisfaction.

The secondary outcomes assessed in this study included VAS scores recorded at 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after surgery, the consumption of patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) sufentanil administered at 24 h postoperatively, and blood glucose levels measured both pre-operation and at 2 and 6 h postoperatively. Furthermore, the incidence of adverse reactions such as drowsiness, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, itching, respiratory depression, and atelectasis from postoperative to discharge was also recorded. Other secondary outcomes evaluated were the time taken for the first ambulation, the interval until chest drain removal, and the length of postoperative hospital stay.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on pain satisfaction scores post-operation, the primary outcome measure. During the pilot testing phase, which involved 20 patients, the observation group showed a mean pain satisfaction score of 8.4 (SD 0.9), whereas the control group had a mean score of 7.7 (SD 1.0). Using MedSci Sample Size Tools, a sample size of 32 patients per group was determined, with a power of 0.8 and an alpha of 0.05. To account for a potential 10% data loss rate, it was decided to include 40 patients in each group.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 statistical software. Quantitative data following a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using Student’s t-test. Variables with a skewed distribution were reported as median (quartile) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Count data were expressed as numbers (percentages) and analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test. For all analyses, a P value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TTPB:

-

Thoracoscopy-guided thoracic paravertebral block

- UTPB:

-

Ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- PaO2 :

-

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen

- PaCO2 :

-

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- PCIA:

-

Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia pump

References

R S, Z. et al. [Cancer Incidence and Mortality in China, 2022]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 46, (2024).

Jedlička, V. Surgical treatment of lung cancer. Klin Onkol. 34, 35 (2021).

Matthew, F. et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic versus robotic-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Innovations 12, 259 (2017).

Xiaoyun, D., Huijun, Z. & Huahua, L. Early ambulation and postoperative recovery of patients with lung cancer under thoracoscopic surgery-an observational study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 18, 136 (2023).

Xia, X. et al. Comparison of thoracoscopy-guided thoracic paravertebral block and ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block in postoperative analgesia of thoracoscopic lung cancer radical surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Ther. 13, 577 (2024).

Lihong, H., Xia, X., Hui, T. & Jinxian, H. Effect of single-injection thoracic paravertebral block via the intrathoracic approach for analgesia after single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic lung wedge resection: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Ther. 10, 433 (2021).

Kateryna, S., Kay, L., Shivaditya, C., Divya, S. & Karina, G. A review of the paravertebral block: benefits and complications. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 27, 203 (2023).

Wenhui, Z., Jianbo, Z., Leilei, H. & Zhihang, T. Analgesic effect of thoracic paravertebral block on patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy under general anesthesia. Pak. J. Med. Sci. Q. 39, 1774 (2023).

Nagalingeswaran, A. et al. Ropivacaine: A novel local anaesthetic drug to use in otorhinolaryngology practice. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 73, 267 (2021).

Rajagopalan, V., Anand, P., Krishnamoorthy, K. & Prabuvel, N. Comparison of morphine, dexmedetomidine and dexamethasone as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block for postoperative analgesia-a randomized controlled trial. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 37, 102 (2021).

Pehora, C., Pearson, A. M., Kaushal, A., Crawford, M. W. & Johnston, B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Datab. Syst. Rev. 11, 1770 (2017).

Sihag, S., Kosinski, A. S., Gaissert, H. A., Wright, C. D. & Schipper, P. H. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a comparison of early surgical outcomes from the society of thoracic surgeons national database. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 101, 1281 (2015).

Kyle, M. & Keleigh, M. Pain management in thoracic surgery. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 30, 339 (2020).

Dan, Y. & Xi, Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery program focusing on chest tube management improves surgical recovery after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 19, 253 (2024).

Pawa, A., Wojcikiewicz, T., Barron, A. & El-Boghdadly, K. Paravertebral blocks: Anatomical, practical, and future concepts. Current Anesthesiol. Rep. (Philadelphia). 9, 263–270 (2019).

Yoshikane, Y. et al. Continuous paravertebral block using a thoracoscopic catheter-insertion technique for postoperative pain after thoracotomy: A retrospective case-control study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 12, 1 (2017).

Lihong, H., Xia, X., Weiyu, S. & Jinxian, H. Feasibility and effectiveness of multi-injection thoracic paravertebral block via the intrathoracic approach for analgesia after thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy. Esophagus 18, 513 (2021).

Rosenfeld, D. M. et al. Perineural versus intravenous dexamethasone as adjuncts to local anaesthetic brachial plexus block for shoulder surgery. Anaesthesia 71, 380–388 (2016).

Cummings, K. C. III. et al. Effect of dexamethasone on the duration of interscalene nerve blocks with ropivacaine or bupivacaine. Br. J. Anaesth. 107, 446–453 (2011).

Ren, H. et al. Dexamethasone inhibits Il-8 via glycolysis and mitochondria-related pathway to regulate inflammatory pain. BMC Anesthesiol. 23, 317 (2023).

Desai, N., Kirkham, K. R. & Albrecht, E. Local anaesthetic adjuncts for peripheral regional anaesthesia: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 76, 100–109 (2021).

El-Boghdadly, K., Pawa, A. & Chin, K. J. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: Current perspectives. Local Reg. Anesth. 11, 35–44 (2018).

Julio, F. Jr. et al. Opioid versus opioid-free analgesia after surgical discharge: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 399, 2280 (2022).

Chenchen, Z. et al. The role of ultrasound-guided multipoint fascial plane block in elderlypatients undergoing combined thoracoscopic-laparoscopic esophagectomy: A prospective randomized study. Pain Ther. 12, 841 (2023).

Melanie, C. et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: The consort pro extension. JAMA 309, 814 (2013).

Jia-Qi, C. et al. Effect of perineural dexamethasone with ropivacaine in continuous serratus anterior plane block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J. Pain Res. 15, 2315 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the patients who participated in this project.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ningbo Health Science and Technology Project Fund 2023Y04 in Zhejiang, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kewei Wu and Lihong Hu designed the study and submitted the manuscript. Shuyu Deng and Xufeng Zhang collected and analyzed the data. Dawei Zheng participated in the surgical operation. Kewei Wu drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lihuili Hospital, Affiliated to Ningbo University (Approval number: KY2023SL340-01). All participants included in the study signed their informed consents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, KW., Deng, SY., Zhang, XF. et al. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant with ropivacaine in thoracoscopy guided thoracic paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in thoracic surgery. Sci Rep 15, 5038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89064-3