Abstract

The terrestrial environment is a significant source of anthropogenic debris emissions. While most studies on anthropogenic debris focus on the marine environment, our research delves into the effects of human activity on anthropogenic debris ingestion by studying the carcasses of feral pigeons. From January to June 2022, we collected the gastrointestinal tracts (GI tracts) of 46 pigeon carcasses in Taipei, Taiwan’s capital city. The results revealed that 224 anthropogenic debris samples were found, with the dominant form being fibers (71.9%), which are primarily black (29.9%). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) revealed that the main component of anthropogenic debris is polyethylene (PE) (20.5%), followed by anthropogenic cellulose (19.2%) and various other plastics. This study revealed that the amount of anthropogenic debris and chemical composition in the GI tract significantly increase with increasing human activity. These results prove that feral pigeons are valuable indicators for monitoring anthropogenic debris pollution in urban ecosystems. On the other hand, past research focused on analyzing microplastics, but we confirmed that the GI tract of pigeons has a high proportion of anthropogenic cellulose. Importantly, future studies should consider the potential impacts of anthropogenic cellulose in terrestrial ecosystems, as this could have significant implications for ecosystem health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic debris, a term used to describe human-made waste and product losses1, has become a global concern and has accumulated in various environments and organisms2,3,4. This debris includes a significant amount of plastic, and the large amount of plastic produced has made plastic pollution a global environmental issue4. Most studies related to plastic pollution have focused on aquatic environments, especially oceanic waters5. Nevertheless, the amount of plastic litter dumped on land yearly is 4–23 times greater than that dumped in the ocean6. Therefore, research on how terrestrial environments and ecosystems are harmed by plastic emissions still needs to be conducted.

In the terrestrial environment, many factors contribute to plastic debris, including personal care products, daily necessities, the wear of automobile tires, dust from vehicles, and many kinds of human necessities6,7,8. Plastic debris that enters the environment will continuously break into smaller sizes. During this breakdown, the plastic debris volume, charge, color, and appearance change, leading to varying bioavailabilities9. Plastic debris smaller than 5 mm is known as microparticles9,10. Many studies have shown that microparticles pass through different trophic levels in the food chain and negatively affect organisms11,12,13. For example, microplastics delay sexual maturity in female Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) and increase the likelihood of epididymal intraepithelial cysts in males1.

In addition to plastic debris, anthropogenic cellulose derived from textiles, carpets, wet wipes, care products, cigarette filters, and other products can also accumulate in animals14,15,16. While the most common celluloses are natural sources such as cotton and wool, colorants, finishes, antimicrobial agents, and ultraviolet light stabilizers can have severe adverse effects on organisms15,17. For example, dye (Direct Red 28) is considered carcinogenic for vertebrates18. Anthropogenic celluloses, which are more durable and persistent, tend to accumulate in the environment and in organisms14. Over half of the anthropogenic debris was rayon, made of cellulose compounds, ingested by fish in the English Channel3.

Birds are highly vulnerable to the accumulation of various environmental contaminants through bioaccumulation and biomagnification19,20. Common reasons for birds ingesting anthropogenic debris include food chain transfer, attraction by the smell of the debris, and accidental ingestion12,21,22. Animal experiments have investigated the adverse effects of anthropogenic debris on birds and other organisms1,23. However, these studies often fail to represent observed conditions owing to the limitations of the anthropogenic debris used (size, shape, type, and particle mixture) and the differences in exposure conditions compared with those in the field environment24,25. In addition, most research has focused on the marine environment, leading to a significant gap in knowledge concerning terrestrial birds25,26. Therefore, scientists, environmentalists, policymakers, and conservationists must actively monitor anthropogenic debris from terrestrial birds.

Given the variation in bird composition by geographic area and the type of anthropogenic debris across species21,26, the use of widely distributed species is crucial. This approach facilitates the comparison of research results from different environments and enables comparisons across geographical scales. The feral pigeon, a common exotic species in most countries, is expected to be uniquely suitable because its foraging range overlaps with that of humans27. In this study, we used feral pigeons as monitoring species to establish primary data on anthropogenic debris ingestion. The objectives of this study were to understand the effects of anthropogenic debris on terrestrial birds, examine sex differences in anthropogenic debris accumulation, and assess the relationships between human activities and anthropogenic debris accumulation. Finally, the feasibility of the use of feral pigeons as bioindicators for monitoring anthropogenic debris pollution in urban areas was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Research areas and sample collection

From January to June 2022, the carcasses of feral pigeons were collected at least once a week at 14 sampling sites in Taipei City, Taiwan. The foraging range of feral pigeons in the city is approximately 0.3 km28; therefore, a radius of 0.3 km around the hotspot was established for sampling (Fig. 1). The carcasses were collected daily between 4:00 and 6:00 in the early morning to minimize opportunities for being trampled by cars or removed by cleaning teams. Because the city was cleaned daily, the carcasses were collected to ensure that the feral pigeons died within 24 h. Only the complete carcasses without decomposition were analyzed to reduce bias.

Location and degree of anthropization for feral pigeon carcass collection. (a) Map of Taiwan and the location of Taipei city, where this study was conducted. (b) Locations of the 14 sampling sites in Taipei city. The English letters represent abbreviations for the names of the sampling sites, i.e., a: Guandu, b: Huajiang, c: Jihe, d: Dalongdonge, e: Shuanglian, f: Zhongzheng, g: Rongxing, h: Huashan, i: Chingmei, j: Minsheng, k: Guangfu, l: Wuxing, m: Yingfeng, and n: Songshan. The circles represent the 0.3 km range around the hotspots, while the colors of the circles represent different degrees of anthropization. The green space on the map indicates that the land belongs to a park, meadow, hill, or forest, and the mixed area indicates a school or airport.

After collection, the carcasses were immediately transported to the laboratory at National Taiwan University. Weight (g), subcutaneous fat mass, intestinal fat mass, and muscle shape were recorded during dissection to indicate the body conditions of individual pigeons29. The sex of each carcass was determined based on the presence of testes or ovaries, and each carcass was categorized by male, female, or unknown sex. The complete GI tract, from the esophagus to the large intestine, was subsequently collected21. The GI tract was wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent contact with the plastic bag, thereby reducing particulate contamination during the experimental procedure. The samples were subsequently stored in a −20 °C freezer until chemical digestion.

Tissue pretreatment

The GI tract of each feral pigeon was placed in a 500 ml flask, and 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) was added at a volume approximately three times greater than that of the GI tract. The flask was placed in an incubator at 65 °C. After thorough digestion at 65 rpm for 48 h, the flask was moved to room temperature for 24 h, after which KOH was added to completely decompose the organic matter21. Most anthropogenic debris cannot be destroyed by 10% KOH30; therefore, most anthropogenic debris was retained during chemical digestion.

Each lysate from the GI tract underwent a meticulous filtration process via a vacuum glass filter device. It passed through glass cellulose filter paper with a pore size of 1.0 μm. The filter paper was then meticulously removed via a nipper, stored on a glass plate, and placed in an oven at 60 °C for a thorough drying process of 48 h.

Quantification and characterization of anthropogenic debris

The dried filter papers were examined under a dissecting microscope (Olympus SZX16). Debris without apparent cellular structures was classified as suspicious debris, and each filter paper was examined three times to ensure that no debris was overlooked. When suspicious debris was found, it was marked with black ink for further investigation.

EPview V1.4 software was used to measure the maximum length (mm) of the debris, and the debris type and color were classified. The types of debris were classified into seven categories31: fragment, fiber, film, pellet, rubber, foam, and wax. The colors of the debris were characterized on the basis of past research20. However, owing to the possible discoloration of anthropogenic debris during the chemical digestion process32, the white-transparent category was first separated into white and transparent groups, and seven additional colors were further classified: gray/silver, black, blue/purple, green, orange/brown, red/pink, and yellow.

After a preliminary examination under a dissecting microscope, the chemical compositions of all the marked pieces of suspicious debris were examined via FTIR. The FTIR instrument was composed of a Shimadzu AIM-9000 and Shimadzu IRTracer-100 in series. The optical mode was set to reflection mode. First, the spectral background value of each piece of glass cellulose filter paper was established. Second, five thinner surfaces of debris were selected for spectrum measurements, and the spectrum was obtained by scanning each surface 16 times, so each fragment had 80 spectral results. The AIMsolution software was used to fit the 80 spectra into one synthetic spectrum. The synthesized spectrum was compared with the built-in substance database of 12,000 substances via the algorithms developed by the company. The criteria for identifying specific chemical compounds of individual debris included that the matching score of a substance was greater than 700 points and that the substance appeared more than three times among the first five estimations. The debris was classified as unknown anthropogenic debris when it did not match the above criteria.

The anthropogenic debris observed in this study included three types: plastic, anthropogenic cellulose, and unknown anthropogenic debris. The former two types were directly identified by the FTIR plastic, whereas the last type had spectral matching failure. Notably, anthropogenic cellulose was identified as cellulose through FTIR, but the debris exhibited visible staining and unnatural colors or textures33,34. Unknown anthropogenic objects usually have different structures, unlike their counterparts, which have natural structures such as a cell wall.

Quality assurance and quality control

Dissection and tissue pretreatment were completed in a fume hood to prevent external plastic contamination, e.g., plastic falling from the air. All the metal dissection tools, glass beakers, and flasks were cleaned with aqua regia and then rinsed three times with 1.0 μm filtered, deionized water. All of the clean equipment was wrapped with aluminum foil to avoid contamination.

During the dissection process, experienced researchers with white lab coats conducted dissections bare-handedly and collected each pigeon’s GI tract within five minutes. During the tissue pretreatment, an additional blank sample was used for every 10 samples. If one debris sample with a similar shape, color, or component was found in both the collected and blank samples, the collected sample was considered contaminated, and the debris was removed. No debris was found in any of the blank samples throughout the experimental process, indicating the validity of our experiments in this study.

Degree of human activity

The degree of human activity was calculated on the basis of four factors: building area, road area, population, and market presence. The building and road areas within a 0.3 km radius were calculated on the basis of aerial images from 2021 by the Taipei City Historical Mapping and Data Display System via QGIS 3.24.3 geographic information system software. The population of each sampling site was meticulously and comprehensively calculated monthly on the basis of the data recorded by the Taipei Civil Affairs Bureau and the New Taipei Civil Affairs Bureau. The average population for each village from January 2021 to June 2022 was used. The proportional area of each village within the sampling range was subsequently calculated, the population for each village within a radius of 0.3 km was calculated on the basis of the proportional area, and the sum was used as the population in the sample area. The existence of open markets, such as traditional and night markets, within a 0.3 km radius of the sampling site was defined as market presence, whereas closed markets, e.g., markets inside buildings, were not included in the calculation because of the inability of feral pigeons to enter. We then ranked the building area, road area, population, and market presence at each sampling site, assigning corresponding points. The degree of human activity belonging to each sampling site was obtained by summing the corresponding points. The anthropization scores were ultimately divided into three groups: low, medium, and high. Among the 14 sampling sites, 6, 4, and 4 were classified as low, medium, and high, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical analysis

Our research methodology, followed by previous studies that used the amount of anthropogenic debris as the quantitative unit20,26,35, has allowed us to understand the three levels of anthropization and obtain the means ± SEs of the amount of anthropogenic debris in the GI tract of feral pigeons. The frequency of occurrence of anthropogenic debris (FO%) was calculated as the number of feral pigeons with at least one piece of anthropogenic debris divided by the number of samples, and the result was converted to a percentage as follows35:

The data we obtained did not have a normal distribution according to the Shapiro–Wilk test. Therefore, the Kruskal‒Wallis test was used to examine differences in weight, body condition, sex, number of anthropogenic debris, and total chemical components (included plastic, anthropogenic cellulose, and unknown anthropogenic debris) in the GI tract of feral pigeons with different degrees of anthropization. This test was also used to determine whether there were differences in the amount of anthropogenic debris and chemical composition between the sexes. If there were significant differences, Duncan’s multiple range test, a crucial post hoc test, was used to perform comparisons to determine the source of the differences. This study used Spearman’s rank correlation analysis to assess the correlation between the amount of anthropogenic debris and the weight and body condition of feral pigeons. The Mann‒Whitney U test was used to determine whether there were differences in the amount of anthropogenic debris in the GI tracts of feral pigeons between sites with and without markets.

Additionally, we conducted a detailed data analysis to investigate the effects of human activities and biological factors on the amount of anthropogenic debris ingested by feral pigeons. We used a generalized linear model (GLM) with a Poisson distribution, and the factors used for constructing the model included the degree of anthropization, the weights of the carcasses, the birds’ body conditions, and the birds’ sex. The optimal model solution was found by comparing the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values of the models. The data were compiled via EXCEL version 16.70, and R version 4.2.0 was used for statistical analysis and data visualization.

Results and discussion

Anthropogenic debris typologies

In this study, 43 feral pigeons were collected at 14 sampling sites (Supplementary Table S2). Finally, 224 pieces of anthropogenic debris were discovered in the GI tract of 43 feral pigeons. The average length of the debris was 1.45 ± 1.49 mm, with the longest piece measuring 8.37 mm and the shortest piece measuring 0.09 mm. The average maximum length of anthropogenic debris from feral pigeons was 1.45 ± 1.49 mm, similar to that reported in studies on Asian terrestrial birds26. However, the minimum length of anthropogenic debris recorded in this study is 0.09 mm, significantly shorter than the value reported in previous studies of Asian terrestrial birds, which was 0.5 mm26. These results indicate that the length of anthropogenic debris ingested by terrestrial birds in Asia is much shorter than previously considered in the literature, underscoring the need to use smaller-pore-size membranes during the filter process.

The appearances and colors of the anthropogenic debris collected from the feral pigeons were remarkably diverse, particularly those of the anthropogenic debris (Supplementary Fig. S1). Among the 224 pieces of anthropogenic debris obtained, the majority were fibers (71.9%), followed by fragments (18.8%), and no wax particles were observed (Fig. 2a). Our study revealed a pressing global trend that demands immediate attention. This prevalence is not unique to feral pigeons, as observed in other terrestrial birds21,26,34,36. The results of abiotic samples from terrestrial environments further underscore the urgency of this issue, with fiber being the primary form of anthropogenic debris37,38.

The primary color of the anthropogenic debris was black (29.9%), followed by blue/purple (21.0%), transparent (16.5%), and other colors (Fig. 2b). This finding is consistent with that of the Barn owl (Tyto alba)39. However, debris color varies among species and environments21,26,39. For example, the primary colors of the debris observed in 17 species of terrestrial birds in China were green, red, and blue26. The primary colors of the debris collected from the red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) were blue and transparent21. This variation may be due to differences in the sample pretreatment methods used in each study. The lack of international consensus and a standardized process hamper our understanding of this issue, highlighting the need for further research in this area40. In addition, many wildlife are visual predators that look for prey on the basis of color41or have a feeding preference for specific colors42; these traits may also increase the likelihood of anthropogenic debris of a specific color being ingested and passed through the food chain. However, our perspective suggests that birds with larger body sizes are less likely to actively choose to ingest microscopic anthropogenic debris of a specific color21. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the color composition of anthropogenic debris in the environment caused differences in the color of debris in the GI tract.

The FTIR results showed that many civilian plastic components were found in feral pigeons. The plastic components accounting for the most significant proportions of the debris were PE (20.54%), PP (10.27%), and PVC (9.38%), all of which were found in people’s livelihood necessities (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). Furthermore, all three plastic components were found in high numbers in the high anthropization site (Supplementary Fig. S3). PE is a common raw material for food containers such as plastic bags, garbage bags, beverage bottles, and cans. PP can also make plastic containers, while PVC is used in hard and soft household products43. PE and PP are common plastic particles in the environment of northern Taiwan44,45and are two types of plastic components. They have become the most widely used polymers for human society due to their ease of processing and low costs46.

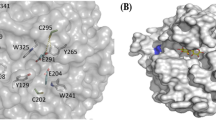

Chemical compositions of anthropogenic debris in feral pigeons. The vertical axis represents the chemical composition of the debris, the horizontal axis represents the amount of debris, and the proportion is shown after the bar graph. The orange bar represents the plastic composition, the green bar represents the unknown, and the blue bar represents anthropogenic cellulose.

After plastic components, anthropogenic celluloses were the second most abundant debris type (19.20%; Fig. 3). This result confirms that plastic is not the only anthropogenic debris ingested by wild birds, Similar to research in recent years34,47,48. Given that the composition of anthropogenic cellulose debris cannot be identified on the basis of its appearance, we believe that it is necessary to broaden the examination of anthropogenic debris to include non-plastic components in future research.

Feral pigeons can be used to monitor anthropogenic debris

According to the Kruskal‒Wallis test, there were no significant differences in weight, body condition, or sex among the different levels of anthropization sites. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the weight or body condition of pigeons collected during different seasons. These results indicated that the weight, body condition, and sex composition of the pigeons collected at the three anthropization levels did not differ, suggesting that the effects of biotic factors on the ingestion and accumulation of anthropogenic debris in the GI tracts of pigeons should be excluded. However, the Kruskal‒Wallis test revealed significant differences in the amount of anthropogenic debris collected from the different degrees of anthropization (H = 32.20, p < 0.001, n = 43). Duncan’s multiple range test revealed that at the sample sites with high anthropization levels, an average of 8.71 ± 2.33 pieces of anthropogenic debris were found in the GI tract, which was significantly greater than the medium level of anthropization (p < 0.001). The average amount of anthropogenic debris in the feral pigeons from the medium-anthropization sites was 5.07 ± 2.14, which was significantly greater than that from the low-anthropization sites, where an average of 1.89 ± 1.52 pieces of anthropogenic debris were observed (p < 0.001; Fig. 4a).

The Kruskal‒Wallis test also revealed significant differences in the number of chemical components found in the anthropogenic debris in the GI tracts of the feral pigeons among the sample sites with different levels of anthropization (H = 27.17, p < 0.001, n = 43). Duncan’s multiple range test revealed that the GI tracts with a high degree of anthropization had an average of 4.86 ± 1.61 chemical components, which was more significant than the medium degree of anthropization, with 3.38 ± 1.32 chemical components (p < 0.01), and more significant than the low degree of anthropization, with 1.42 ± 1.02 chemical components (p < 0.001; Fig. 4b).

The frequency of anthropogenic debris occurrence in pigeons increased with anthropization (Supplementary Table S3). The GLM, which solely incorporated the degree of anthropization, demonstrated the lowest AIC value (AIC = 190.51), a crucial indicator of model selection (Table 1). This finding underscored the importance of the degree of anthropization associated with anthropogenic debris in feral pigeons, which was positively correlated (p < 0.001; Table 2). Combining these results, the amount of anthropogenic debris in pigeons increased with increasing levels of anthropization. In past studies, the amount of anthropogenic debris in fish bogue (boops boops) in the Mediterranean Sea has been related to the degree of anthropization49. Our research results confirm that this phenomenon also occurs in terrestrial birds.

Feral pigeons have different dietary preferences than their rock pigeon ancestors. Compare with rock pigeons that ingest grassland seeds, feral pigeons depend more on food provided by humans, especially food scattered by humans (waste food) and human food50,51. According to the Mann‒Whitney U test, the number of anthropogenic debris collected from wild pigeons at sampling sites with a market was significantly greater than that at sampling sites without a market (M with market = 7.00 ± 2.70, M without market = 2.55 ± 2.65, p < 0.001, n = 43; Fig. 5). In this study, pigeons in Taipei often flew to the market in flocks to scavenge food from garbage piles or pick up trash discarded at stalls; these behaviors may cause the market to become a pathway for human-made waste diversion.

Pigeons, a species that has successfully colonized nearly all major cities worldwide, share a unique symbiotic relationship with humans50,51. On the other hand, pigeons are exotic bird species found in many regions27. The active or passive sample collection methods are less contentious than other approaches are and do not pose a threat to native bird populations. The practical implications of this research are profound. Using pigeons as bioindicators can help researchers better understand and mitigate anthropogenic debris pollution in urban areas, significantly contributing to wildlife conservation efforts. For example, northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis), a seabird, has chosen to represent the ecological quality objective in the North Sea, with a target of less than 10% of birds accumulating 0.1 g of plastic in their bodies29. Recent studies have shown that common swift (Apus apus) and common house martin (Delichon urbicum) are bioindicators of anthropogenic debris in terrestrial air48. Although the study is already complete, to our knowledge, no bird species have yet been proposed to represent the ecological quality objective in the terrestrial environment in Asia to support long-term monitoring and environmental litter reduction.

Ecological risk of anthropogenic debris

An average of 6.00 ± 3.66 pieces of anthropogenic debris were observed in the GI tracts of females, 3.81 ± 2.98 in male feral pigeons, and 5.14 ± 3.89 in unknown-sex pigeons. According to the results of the Kruskal‒Wallis test, there was no significant difference in the amount of anthropogenic debris or chemical composition of the debris in the feral pigeons among the three sex groups (Supplementary Fig. S4). The activity range of female feral pigeons is more extensive than that of male pigeons28. This finding is significant, as it suggests that female feral pigeons may be exposed to more diverse pollutants. This surprising equality in exposure to anthropogenic debris suggests that feral pigeons of different sexes are at the same risk. This unexpected result may be due to the high human density in Taipei, which makes it easier to find food, leading to male and female feral pigeons foraging at the same locations.

Anthropogenic debris blocks the intestinal tracts of animals, leading to reduced feeding rates and body weights52,53. In studies on birds, digestive obstruction has been considered to cause a decline in body condition. When intestinal obstruction occurs, birds use their stored body energy to compensate for the energy difference caused by reduced nutrient absorption54. The average body condition of the feral pigeons in this study was 4.8 ± 1.7 points, which is typical29.

The statistical results also revealed that the amount of anthropogenic debris is unrelated to body condition and weight. In addition, the amount of anthropogenic debris observed in feral pigeons is smaller than that associated with decreased weight in seabirds53. Based on the bird’s body size to anthropogenic debris volume ratio, the particle size of the anthropogenic debris ingested by the feral pigeons in this study should not be enough to block the digestive tract, indicating that there is no risk of physical injury due to anthropogenic debris ingestion among feral pigeons.

However, the potential influence of anthropogenic debris at the chemical level must be considered. In an experiment with short-tailed shearwater (Puffinus tenuirostris), ingested plastic debris was shown to transfer chemical substances to the birds’ bodies55. We found a substantial amount of plastic debris and anthropogenic cellulose in the GI tracts of feral pigeons. Both substances contain a cocktail of chemicals14,26; furthermore, pores accumulate on anthropogenic debris in the environment owing to physicochemical reactions, making these particles more likely to adsorb environmental pollutants56. In addition, smaller debris represents a larger surface area ratio and is more toxic to animals10. The sampling sites with greater anthropization had a more comprehensive range of anthropogenic debris lengths and more debris with a small volume (Supplementary Fig. S5). Fiber debris had the widest difference in maximum and shorter lengths among the anthropogenic debris types (Supplementary Fig. S6). Among the anthropogenic debris components, there were more anthropogenic cellulose particles, PE particles, and unknown anthropogenic debris with relatively small lengths (Supplementary Fig. S7).

While some birds can expel indigestible substances, including anthropogenic debris, through pellet vomiting47,57, feral pigeons do not exhibit this behavior. This unique characteristic may lead to more anthropogenic debris remaining in feral pigeons than in other bird species. Our study also revealed that the appearance, volume, and length of anthropogenic debris particles found in terrestrial birds, such as feral pigeons, differ significantly from those found in seabirds58. However, the majority of ecotoxicological studies on anthropogenic debris have focused on marine species12,22,33. This underscores the urgent need for further research to assess the risk of anthropogenic debris to terrestrial wildlife comprehensively.

Recently, the body structures of birds other than the digestive tract have been found to contain anthropogenic debris, indicating that the process by which anthropogenic debris enters the bird body and moves between organs may be diverse59,60. This diverse interaction of birds with anthropogenic debris in the environment, which has diverse sizes, colors, appearances, and compositions, underscores the need for research to reconsider how such complex pollutants are defined. Moreover, researchers should develop and design analysis methods based on the characteristics of different types of anthropogenic debris, as this will be crucial in understanding the full extent of the impact of anthropogenic debris on wildlife61.

Conclusions

This study presents data on plastic and cellulose pollution using terrestrial birds as indicators in Taiwan for the first time. The results show that human activity increases feral pigeon ingestion of anthropogenic debris, which includes many kinds of plastic and cellulose. Owing to the high overlap between the foraging ranges of feral pigeons and humans and their high dependence on human food, feral pigeons ingest more diverse chemical compositions at sites with relatively high human activity. These results prove that feral pigeons are feasible indicators for monitoring anthropogenic debris in urban ecosystems. Feral pigeons are likely to pick up waste, making markets a potential pathway for the transfer of anthropogenic debris. Although there is no evidence that anthropogenic debris causes a reduction in body weight or body condition in feral pigeons, the particle size of anthropogenic debris in feral pigeons is relatively small; therefore, the possibility of pollution transfer needs future concern.

Data availability

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Roman, L. et al. Is plastic ingestion in birds as toxic as we think? Insights from a plastic feeding experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 665, 660–667 (2019).

Jambeck, J. R. et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 347, 768–771 (2015).

Lusher, A. L., Mchugh, M. & Thompson, R. C. Occurrence of microplastics in the gastrointestinal tract of pelagic and demersal fish from the English Channel. Mar. Pollut Bull. 67, 94–99 (2013).

Van Sebille, E. et al. A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 124006 (2015).

Li, J., Liu, H. & Chen, J. P. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 137, 362–374 (2018).

Horton, A. A., Walton, A., Spurgeon, D. J., Lahive, E. & Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 586, 127e141 (2017).

Sommer, F. et al. Tire abrasion as a major source of microplastics in the environment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18, 2014–2028 (2018).

Wright, S. L., Ulke, J., Font, A., Chan, K. L. A. & Kelly, F. J. Atmospheric microplastic deposition in an urban environment and an evaluation of transport. Environ. Int. 136, 105411 (2020).

Galloway, T. S., Cole, M. & Lewis, C. Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1–8 (2017).

Jeong, C. B. et al. Microplastic size-dependent toxicity, oxidative stress induction, and p-JNK and p-p38 activation in the monogonont rotifer (Brachionus Koreanus). Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 8849–8857 (2016).

Carbery, M., O’Connor, W. & Palanisami, T. Trophic transfer of microplastics and mixed contaminants in the marine food web and implications for human health. Environ. Int. 115, 400–409 (2018).

Hammer, S., Nager, R., Johnson, P., Furness, R. & Provencher, J. Plastic debris in great skua (Stercorarius skua) pellets corresponds to seabird prey species. Mar. Pollut Bull. 103, 206–210 (2016).

Nelms, S. E., Galloway, T. S., Godley, B. J., Jarvis, D. S. & Lindeque, P. K. Investigating microplastic trophic transfer in marine top predators. Environ. Pollut. 238, 999–1007 (2018).

Athey, S. N. et al. The widespread environmental footprint of indigo denim microfibers from blue jeans. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 7 (11), 840–847 (2020).

Belzagui, F., Buscio, V., Gutiérrez-Bouzán, C. & Vilaseca, M. Cigarette butts as a microfiber source with a microplastic level of concern. Sci. Total Environ. 762, 144165 (2021).

Zhou, H., Zhou, L. & Ma, K. Microfiber from textile dyeing and printing wastewater of a typical industrial park in China: occurrence, removal and release. Sci. Total Environ. 739, 140329 (2020).

Almroth, B. C. et al. Assessing the effects of textile leachates in fish using multiple testing methods: from gene expression to behavior. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111523 (2021).

Remy, F. et al. When microplastic is not plastic: the ingestion of artificial cellulose fibers by macrofauna living in seagrass macrophytodetritus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11158–11166 (2015).

Burger, J. et al. Assessment of metals in down feathers of female common eiders and their eggs from the aleutians: arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, manganese, mercury, and selenium. Environ. Monit. Assess. 143, 247–256 (2008).

Provencher, J. F. et al. Quantifying ingested debris in marine megafauna: a review and recommendations for standardization. Anal. Methods. 9, 1454e1469 (2017).

Carlin, J. et al. Microplastic accumulation in the gastrointestinal tracts in birds of prey in central Florida, USA. Environ. Pollut. 264, 114633 (2020).

Savoca, M. S., Wohlfeil, M. E., Ebeler, S. E. & Nevitt, G. A. Marine plastic debris emits a keystone infochemical for olfactory foraging seabirds. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600395 (2016).

Rist, S. E. et al. Suspended micro-o-sized PVC particles impair the performance and decrease survival in the Asian green mussel Perna viridis. Mar. Pollut Bull. 111, 213–220 (2016).

Phuong, N. N. et al. Is there any consistency between the microplastics found in the field and those used in laboratory experiments? Environ. Pollut. 211, 111–123 (2016).

Prokić, M. D. et al. Studying microplastics: lessons from evaluated literature on animal model organisms and experimental approaches. J. Hazard. Mater. 414, 125476 (2021).

Zhao, S., Zhu, L. & Li, D. Microscopic anthropogenic litter in terrestrial birds from Shanghai, China: not only plastics but also natural fibers. Sci. Total Environ. 550, 1110–1115 (2016).

Haag-Wackernagel, D. & Moch, H. Health hazards posed by feral pigeons. J. Infect. 48, 307–313 (2004).

Rose, E., Nagel, P. & Haag-Wackernagel, D. Spatio-temporal use of the urban habitat by feral pigeons (Columba livia). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 60, 242–254 (2006).

Van Franeker, J. Save the North Sea Fulmar-Litter-EcoQO manual part 1: collection and dissection procedures. Alterra (2004).

Dehaut, A. et al. Microplastics in seafood: Benchmark protocol for their extraction and characterization. Environ. Pollut. 215, 223–233 (2016).

Provencher, J. F., Vermaire, J. C., Avery-Gomm, S., Braune, B. M. & Mallory, M. L. Garbage in guano? Microplastic debris found in faecal precursors of seabirds known to ingest plastics. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 1477–1484 (2018).

Cole, M. et al. Isolation of microplastics in biota-rich seawater samples and marine organisms. Sci. Rep. 4, 4528 (2014).

Bourdages, M. P., Provencher, J. F., Baak, J. E., Mallory, M. L. & Vermaire, J. C. Breeding seabirds as vectors of microplastics from sea to land: evidence from colonies in Arctic Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 764, 142808 (2021).

Wayman, C. et al. Accumulation of microplastics in predatory birds near a densely populated urban area. Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170604 (2024).

Lourenço, P. M., Serra-Gonçalves, C., Ferreira, J. L., Catry, T. & Granadeiro, J. P. Plastic and other microfibers in sediments, macro invertebrates and shorebirds from three intertidal wetlands of southern Europe and West Africa. Environ. Pollut. 231, 123–133 (2017).

Sherlock, C., Fernie, K. J., Munno, K., Provencher, J. & Rochman, C. The potential of aerial insectivores for monitoring microplastics in terrestrial environments. Sci. Total Environ. 807 (1), 150453 (2022).

Corradini, F. et al. Evidence of microplastic accumulation in agricultural soils from sewage sludge disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 671, 411–420 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. Microplastic and mesoplastic pollution in farmland soils in suburbs of Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 242, 855–862 (2018).

Nessi, A. et al. Microplastic contamination in terrestrial ecosystems: a study using barn owl (Tyto alba) pellets. Chemosphere 308, 136281 (2002).

Provencher, J. F. et al. Proceed with caution: the need to raise the publication bar for microplastics research. Sci. Total Environ. 748, 141426 (2020).

Boerger, C., Lattin, M., Moore, G. L., Moore, C. J. & S. L. & Plastic ingestion by planktivorous fishes in the North Pacific Central Gyre. Mar. Pollut Bull. 60 (12), 2275–2278 (2010).

Okamoto, K., Nomura, M., Horie, Y. & Okamura, H. Color preferences and gastrointestinal-tract retention times of microplastics by freshwater and marine fishes. Environ. Pollut. 304, 119253 (2022).

Liao, C. P., Chiu, C. C. & Huang, H. W. Assessment of microplastics in oysters in coastal areas of Taiwan. Environ. Pollut. 286, 117437 (2021).

Bancin, L. J., Walther, B. A., Lee, Y-C. & K, A. Two-dimensional distribution and abundance of micro- and mesoplastic pollution in the surface sediment of Xialiao Beach, New Taipei City, Taiwan. Mar. Pollut Bull. 140, 75–85 (2019).

Kunz, A., Walther, B. A. & L¨owemark, L. Distribution and quantity of microplastic on sandy beaches along the northern coast of Taiwan. Mar. Pollut Bull. 111, 126–135 (2016).

Pelegrini, K., Maraschin, G. M., Brandalise, R. N. & Piazza, D. Study of the degradation and recyclability of polyethylene and polypropylene present in the marine environment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136 (48), 48215 (2019).

Wayman, C. et al. Unraveling Plastic Pollution in Protected Terrestrial raptors using regurgitated pellets. Microplastics 3 (4), 671–684 (2024).

Wayman, C. et al. The potential use of birds as bioindicators of suspended atmospheric microplastics and artificial fibers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 282, 116744 (2024).

Tsangaris, C. et al. Using Boops boops (osteichthyes) to assess microplastic ingestion in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut Bull. 158, 111397 (2020).

Sol, D., Santos, D. M., García, J. & Cuadrado, M. Competition for food in urban pigeons: the cost of being juvenile. Condor 100, 298–304 (1998).

Spennemann, D. H. & Watson, M. J. Dietary habits of urban pigeons (Columba livia) and implications of excreta pH – a review. Eur. J. Ecol. 3 (1), 27–41 (2017).

Welden, N. A. & Cowie, P. R. Long-term microplastic retention causes reduced body condition in the langoustine, Nephrops norvegicus. Environ. Pollut. 218, 895–900 (2016).

Spear, L. B., Ainley, D. G. & Ribic, C. A. Incidence of plastic in seabirds from the tropical pacific, 1984–1991: relation with distribution of species, sex, age, season, year and body weight. Mar. Environ. Res. 40, 123–146 (1995).

Ryan, P. Effects of ingested plastic on seabird feeding: evidence from chickens. Mar. Pollut Bull. 19, 125–128 (1988).

Tanaka, K. et al. Accumulation of plastic-derived chemicals in tissues of seabirds ingesting marine plastics. Mar. Pollut Bull. 69, 219–222 (2013).

Mato, Y. et al. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 318–324 (2001).

Winkler, A. et al. Occurrence of microplastics in pellets from the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) along the Ticino River, North Italy. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 41731–41739 (2020).

Bond, A. L., Provencher, J. F., Daoust, P-Y. & Lucas, Z. N. Plastic ingestion by fulmars and shearwaters at Sable Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Mar. Pollut Bull. 87, 68–75 (2014).

Liu, W. et al. Varying abundance of microplastics in tissues associates with different foraging strategies of coastal shorebirds in the Yellow Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 865, 161417 (2023).

Tokunaga, Y. et al. Airborne microplastics detected in the lungs of wild birds in Japan. Chemosphere 321, 138032 (2023).

Rochman, C. M. et al. Rethinking microplastics as a diverse contaminant suite. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 38, 703–711 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We want to express our profound gratitude to the Taipei City Animal Protection Office for their unwavering support and resources, which have been pivotal in our understanding of the population distribution of feral pigeons in Taipei City. The research was significantly advanced by the support of the Taipei Zoo, Kinmen National Park Research Fund (KM1137002), and the Ocean Conservation Administration in Taiwan, whose contributions were instrumental in our anthropogenic debris analysis. We also want to thank Alexander Kunz, Jun-Pei Liao, Siña Mariella, and Ning Yan for their invaluable sharing of their experimental experience in analyzing anthropogenic debris.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.T.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. W.T.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing, Visualization. C.Y.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision. S.Y.H.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision. C.H.H.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. C.H.K.: Resources. C.H.H.: Resources. H.W.Y.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, WT., Yang, WT., Ko, CY. et al. Using feral pigeon (Columba livia) to monitor anthropogenic debris in urban areas: a case study in Taiwan’s capital city. Sci Rep 15, 5933 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89103-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89103-z