Abstract

The micromechanical properties of organic matter (OM) and organic pore structures in the over-mature stage are crucial for determining shale reservoir quality and assessing shale gas resource potential. However, there is still debate about the influence of micromechanical properties of OM on the micro-mesopore structures in over-mature shale. In this study, shale cores from the Niutitang Formation have been specifically chosen for OM isolation, adsorption testing, atomic force microscopy examination, and focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) analysis to assess the micromechanical properties of OM and pore structures. The findings indicate that organic micropores and mesopores predominantly exhibit elliptical, circular, or irregular shapes. Organic pores mainly provide pore volume (PV) and specific surface area (SSA) of shale. In the over-mature stage, residual kerogen and pyrobitumen transition towards a graphite structure, increasing Young’s modulus of OM. Additionally, as thermal maturity increases, the absence of a rigid mineral framework and pore fluid pressure results in the compaction of pores, leading to a decrease in PV and SSA. The organic micropores are more vulnerable to collapse and compaction because of the increased brittleness of OM. The organic micropores and mesopores gradually evolve from regular circular and elliptical shapes to irregular shapes during the over-mature stage. The research findings provide valuable insights into the micromechanical mechanism of pore evolution in over-mature marine shale within complex structural regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shale gas has undergone extensive exploration and development, achieving significant success in southern areas of China and northern America1,2,3. The successful exploitation of marine shale within the complex structural regions of southern China has brought about significant breakthroughs in the Chinese shale gas industry4,5. The northern region of Guizhou Province, adjacent to the Sichuan Basin, exhibits considerable potential for further development6. The Niutitang Formation, located north of Guizhou and characterized by several distinctive advantages, has become a favorable stratum for marine shale exploitation.This is attributed to its considerable reservoir thickness, high total organic carbon (TOC) content, high thermal maturity, and dry gas stage 7,8. Analyzing the pore structures of shale, particularly OM pores, is crucial since they significantly influence the storage capacity of shale gas reservoirs and play a significant role in enhancing gas exploration efficiency9,10. OM pores serve as the primary shale gas reservoir, playing a critical role in gas enrichment and migration11. The level of OM pore evolution substantially impacts the total porosity, permeability, and gas adsorption behavior of shale formations. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of pore structure characteristics of shale reservoirs is essential to optimize development strategies and increase the efficiency of shale gas exploration.

OM pores serve as the primary storage area for shale gas, contributing significantly to gas enrichment and migration12,13,14. The development of OM pores significantly influences the overall porosity, permeability, and gas adsorption characteristics of shale reservoirs. To gain a deeper understanding of the characteristics of OM pores, researchers have explored various methods for OM isolation, including OM removal methods, field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) image extraction methods, and chemical extraction techniques15,16,17,18,19. Applying these methods can accurately reveal the structural features of OM pores, providing theoretical support for efficient shale gas exploration. In recent years, there has been extensive discussion on the impact of geochemical parameters on OM pores, particularly focusing on thermal maturity20. The migration and storage capacities of shale gas are profoundly affected by thermal maturity6,21,22. Most studies have concentrated on the impact of thermal maturity on pores structures15,23,24,25. OM pores expand extensively when the Ro value is between 1.5 and 2.5%. When the Ro value reaches 2.5–3.0%, the pore system reaches optimal, generating favorable conditions for shale gas and oil exploration26. OM pores in shale reservoirs undergo a five-stage hydrocarbon production and evolution process27. In the Wufeng-Longmaxi and Niutitang formations, the generative capacity of OM pores is nearing its peak; Increased thermal maturity will lead to a decrease in the PV and SSA of OM pores, while inorganic pores remain relatively unaffected28. At the over-mature stage, due to increased thermal maturity, mesopores and micropores expand and their prevalence increases compared to stages of lower maturity29. However, the complex reactions of pores within other minerals and their response to thermal maturity might explain the relatively weak association found between macropores and thermal maturity30. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate organic micro-mesopores in the over-mature stage.

The micromechanical properties of OM are the primary manifestation of the impact of OM thermal maturity on organic micro-mesopores. Many experts and scholars employ nano-indentation and AFM to examine the micromechanical properties of various shales. Among these methods, AFM is particularly favored due to its high spatial resolution, precise data output, shallow indentation depth, and minimal damage to the sample surface31,32,33. Studies have shown that as thermal maturation increases, the Young’s modulus of OM also rises, leading to the progressive collapse and merging of internally generated nanoscale pores, which ultimately may vanish. Additionally, inertinite exhibits the highest Young’s modulus at comparable levels of thermal maturity, while bitumen displays the lowest. As the Ro value increases, there is a corresponding increase in Young’s modulus across different types of OM34. Consequently, a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between micromechanical properties, OM pore structure, and thermal maturity is essential for understanding the evolution of OM pores in marine shale. Although prior research has extensively discussed factors influencing shale pore structure and its correlation with OM thermal maturity, there is limited research on the micromechanical properties of OM in over-mature marine shale and their impact on pore structure. The effect of OM micromechanical properties on over-mature marine shale pore characteristics is still debated.

To explore the impact of micromechanical properties of OM on pore structure characterization in over-mature marine shale, physics experiments were conducted on shale cores extracted from Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 in the northern Guizhou Niutitang Formation. The study focused on OM isolation and t utilizing AFM to determine the relationship between thermal maturity and the characteristics of both bulk shale and OM pores. Furthermore, an analysis was performed to clarify the relationship between the characteristics of organic micro-mesopore structures and the micromechanical properties of OM. These findings enhance our understanding of the evolution of micromechanical properties in over-mature marine shale pores within complex structural regions.

Geological setting

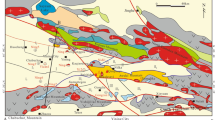

The research location is situated within the northern Guizhou Province of southwest China (Fig. 1a,b). This region exhibits a high degree of similarity in geological structure and evolutionary history to the Yangtze Platform, which influences the distribution and production patterns of shale gas resources23,24,35. It is unique because of the wide distribution of the Cambrian Niutitang Formation, which serves as favorable reservoir conditions, a high TOC, and a high thermal maturity. These geological conditions make the northern Guizhou region an optimal target for marine shale exploration. The geological structure of northern Guizhou is complex, with multiple folds and faults developing in various directions, particularly in the north–south and northeast directions35 (Fig. 1c). Predominantly, these folds exhibit a “compartmentalized” structure, mainly aligned in the northeast, with additional folds occurring in other directions36,37. The reservoir within the Niutitang Formation ranges from 40 to 107 m in thickness and is primarily composed of siliceous and carbonaceous shales38,39.

The geographical setting of the research location and geological structure features: (a) Location of Guizhou province; (b) Location of Northern Guizhou; (c) Unique geological characteristics of Northern Guizhou35.

Shale cores from FC 1, TM 1, and TX 1 wells were selected for the study. Fine-grained shale from the Mingxin Temple Formation forms the reservoir’s roof, while the Dengying and Laobao Formations make up its bottom. The bottom of Wells FC1 and TM1 consists of the dolomitic shale of the Dengying Formation (Fig. 2a), while the bottom of Well TX1 comprises the siliceous shale of the Laobao Formation (Fig. 2b).

Samples and methods

Samples

Shale core samples of the Niutitang Formation were chosen for this investigation from several geographic locations within the complex structural regions of northern Guizhou. After careful selection, six samples were selected from three Wells in Fenggang and Cengong in the Qianbei area for various experiments, each originating from different depths and blocks (Table 1). Various tests were conducted to investigate the mineral composition, TOC, thermal maturity, OM pore structure, micromechanical properties of the shale cores, and OM isolation. These tests included X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, TOC testing, vitrinite reflectance measurement (EqVRo), FIB-SEM and FE-SEM observations, N2 and CO2 adsorption, chemical extraction method, and AFM testing (Fig. 3).

The mineral composition, TOC, and Ro

The mineral composition of the core samples was determined using a Rigaku D/MAX-2600 X-ray diffractometer after the samples were crushed to a mesh size of 200. The instrument was operated at a scanning speed of 2°/min over a range of 2°–90°. The total organic carbon (TOC) content was analyzed using an Elementar vario TOC select instrument, with sample sizes ranging from 100 to 200 mesh. Thermal maturity was evaluated through vitrinite reflectance measurements obtained with a Leitz MVP-3 microscope photometer. Initially, epoxy resin was mixed with the shale samples and stored at 60 °C for 12 h. The samples were then processed by grinding and polishing, followed by calibration against two standard reflectance boards. Reflectance values were determined through the comparative method. In the absence of vitrinite in the Niutitang Formation, the reflectance of bitumen (Rb) was utilized to calculate the equivalent vitrinite reflectance (EqVRo)40.

OM isolation

To investigate the characteristics of the organic matter (OM) pore structures in the cores, OM isolation was carried out separately. The samples were crushed to a particle size of less than 2 mm for isolation. A solution of 6 mol/L HCl and 40% HF was employed to remove carbonates. To prevent the influence of pyrite, the residue was treated again with 6 mol/L HCl. An oscillator was used to separate the OM from the heavy liquid, and the separated OM was washed with distilled water to eliminate any remaining halide ions, which could interfere with subsequent analyses. The isolated OM was frozen for six hours at 5 °C and subsequently dried at 60 °C.

FIB-SEM and FE-SEM

The organic pore structures and morphological characteristics were investigated using a ZEISS Crossbeam 540 FIB-SEM. Observations were conducted at magnifications ranging from 2.5 to 1,000,000. The organic pore structures were performed with a ZEISS Sigma 300 FE-SEM, using magnification settings from 1.2 to 200,000. For sample preparation, a small quantity of powdered sample was affixed to a conductive adhesive and then coated with gold via a Quorum SC7620 sputter coater for approximately 45 s at 10 mA. Finally, the morphology of the samples was observed using FE-SEM at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV. In addition, imaging was carried out at a spatial resolution of 1.0 nm and a minimum working distance of 8.5 mm.

N2 adsorption and CO2 sorption experiments

The N2 adsorption was conducted using the Quantachrome Autosorb IQ for precise characterization of the shale core samples. Initially, the bulk shale samples were ground to a mesh size of 80 and vacuum-degassed for 12 h. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to low-temperature conditions at 77.3 K to obtain the corresponding isothermal adsorption curve. The SSA of the samples was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) equation41. Meanwhile, the CO2 sorption experiments were conducted using the Quantachrome Autosorb IQ. The samples were crushed to less than 100 mesh and decontaminated in a vacuum for 12 h before CO₂ adsorption at 273.15 K (0 °C). Applying the density functional theory (DFT)42 and Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH) models43 to obtain the PV and pore size distribution (PSD) curves.

AFM

Before testing the micromechanical properties of OM in shale, bulk shale core samples were extensively polished using sandpaper with grit sizes ranging from 400 to 5000, achieving relatively smooth experimental surfaces. Subsequently, experiments were conducted using the Bruker Dimension Icon AFM instrument, which was equipped with a cantilever beam with a 2 kHz oscillation frequency and a high scanning resolution of up to 256 × 256 pixels. This mode significantly reduced the load, improved resolution, and accelerated scanning speed, ensuring precision and efficiency in the experimental results44. In the experiment, the Peak Force Tapping Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping (PF-QNM) mode was employed to comprehensively capture the morphology and micromechanical properties of the shale core (Fig. 4). Initially, a detailed scan of a 5 μm × 5 μm surface area of the shale core was conducted using the microscope on the AFM to locate OM. Subsequently, the scanning procedure was then improved in Peak Force mode by modifying the maximum force applied by the probe to the sample surface, ensuring the probe tip remained at least 150 nm away. Pressure was then applied to the surface to bring the probe into contact with the sample, gradually increasing the force in the z-axis until a stable peak force value was reached. Throughout this process, the maximum adhesion force value when the probe exited the sample surface was meticulously recorded, and the detector was repositioned to a distance of 150 nm from the sample surface in preparation for the next cycle45. Through this series of precise operations, critical surface characteristics of the shale core, including surface roughness and modulus, were obtained, contributing to a deeper understanding of shale pore structures and their mechanical properties. Finally, import the data into NanoScope Analysis software for filtering analysis, excluding the values of inorganic minerals with Young’s modulus exceeding 50 GPa. Derjaguin–Muller–Toporov Er was used to calculate the simplified modulus Er :

Diagram of the working mode of AFM; (a) Schematic diagram of the probe; (b) Schematic diagram of the full force-distance45.

The Eqs. (2) and (3) above \({F}_{tip }\) is the force on the tip, \({F}_{adh}\) is the adhesion force, \(R\) stands for the tip radius, and \(d\) signifies the sample deformation. After obtaining the reduced modulus \({E}^{*}\), the Young’s modulus \(E\) of the sample can be determined by combining \({E}^{*}\) with Poisson’s ratio \(v\) where \({E}_{tip}\) and \({v}_{tip}\) represent the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the probe, correspondingly.

A common way to figure out the root-mean-square hardness (Rq) and median roughness (Ra) of the OM is to import the AFM data via the NanoScope Analysis software. These parameters describe the variability in surface morphology and the standard deviation from the baseline plane to the surface. The formulas for calculating Rq and Ra are as follows:

In the Eq. (4), (5), (6), \({N}_{x}\) and \({N}_{y}\) represent the number of scan points with the x-axis and y-axis, respectively; \(z\left(i,j\right)\) denotes the height of the measurement point; and \({z}_{mean}\) is the mean height for all measurement points.

Results

Mineralogy and organic geochemistry

The results of the organic geochemical and mineralogical compositions are summarized in Table 1. The quartz proportion in the three Wells ranges from 49.8 to 72.2%, with an average of 59.08%. The percentage of clay minerals varies from 8.9 to 24.7%, averaging 17.23%. The proportion of feldspar ranges from 7.7 to 10.9% with an average of 8.98%, and the average pyrite content is 5.4–15.5%, with an average of 9.93%. Among these samples, TM1S1 exhibits the highest clay mineral content at 24.7%, while FC1S1 has the lowest at 8.9%. Thus, quartz and clay are the predominant minerals across all three Wells, with lower proportions of feldspar and pyrite. The clay mineral composition, determined by XRD tests, includes illite, montmorillonite, and illite-montmorillonite mixed layers. The combined contents of these three minerals constitute the total clay mineral content.

The average TOC content is 5.95%, ranging from 5.41 to 7.31%. The average Ro is 2.92%, with values varying from 2.32 to 3.72%. The FC1S1 sample shows the highest thermal maturity, while TM1S2 exhibits the lowest. Based on the TOC content and Ro values, it was concluded that all three of the Well samples were over-mature dry gas stage, organic-rich shales.

OM pores

The development of OM pores varies across the northern Guizhou region, and these pores are the primary focus of our research. Notably, the TOC content is above 2% in all three Wells of the Niutitang Formation. Figure 5 illustrates the pore characteristics observed using FIB-SEM. The Well FC1 developed honeycomb-like OM pores characterized by irregular, elliptical forms, bordered by intragranular pores (Fig. 5a,b). The Well TM1 displays fewer OM pores, primarily circular, with quartz and adjacent intragranular pores surrounding the OM (Fig. 5c,d). Meanwhile, the Well TX1 exhibits a rich diversity of OM pores that include numerous circular and irregular shapes (Fig. 5e,f).

Figure 6 illustrates characteristics of OM pores observed using FE-SEM. In Well FC1, large pores are embedded with smaller pores, exhibiting elliptical and irregular shapes, creating a sponge-like distribution (Fig. 6a,b). The OM pores in Well TM1 are primarily elliptical and circular (Fig. 6c,d), while those in Well TX1 show irregular, circular, and elliptical shapes (Fig. 6e,f). The presence of large pores embedded within smaller ones facilitates the occurrence and migration of shale gas in all three Wells. Notably, the slight variation in pore morphology observed in Well TM1 suggests significant heterogeneity in the development of shale OM pores. Furthermore, the honeycomb-like pattern of OM pores in Wells FC1 and TX1 indicates a strong relationship between the appearance of OM pores and the bulk shale.

Bulk shale and OM pore structure characterization

N2 adsorption and CO2 sorption analysis

Figure 7 illustrates the PSD curves of OM and bulk shales for N2 and CO2 adsorption, providing insights into the gas storage capacity of these samples. The isothermal CO2 sorption curves (Fig. 7c,d) show an increase in all samples with relative pressure. In contrast, the N2 adsorption curves reveal that at relatively high pressures (P/P0 = 0.989), the absorbed gas volume reaches its maximum value. All curves exhibit hysteresis loops at higher pressures, but these loops close at lower relative pressures (Fig. 7a,b). By analyzing low-temperature nitrogen adsorption data, we can conclude that micropores demonstrate a strong adsorption capacity under low relative pressure conditions. As pressure decreases, these micropores release gas rapidly, resulting in a sudden closure of the hysteresis loop. This phenomenon extends to and can reach the lowest pressure46. This phenomenon may be triggered by incomplete desorption of N2, irreversible molecules being absorbed in pores with approximate adsorbate molecular widths, or OM expansion during adsorption47. Importantly, in all three Wells, FC1, TM1, and TX1, the N2 and CO2 adsorption curves of OM show higher gas adsorption volumes than those for bulk shale, indicating better development of OM pore.

SSA and PV

Typically, pore structure characteristics include PV, SSA, PSD, and pore connectivity. To comprehensively describe the multiscale pore development of both the bulk shale and OM, the BET model (2 nm < Φ < 50 nm) and the DFT model (0 nm < Φ < 2 nm) were used to calculate the SSA of samples. Subsequently, the PV of the samples from the three Wells were obtained using the BJH and DFT model, as shown in Table 2.

The average SSA values for Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 are 13.144 m2/g, 12.786 m2/g, and 17.713 m2/g, respectively. The average SSA of OM pores values is 59.159 m2/g, 51.921 m2/g, and 37.643 m2/g for three Wells. Furthermore, relying on the DFT model. Firstly, an appropriate atomic model needs to be constructed. Secondly, suitable exchange–correlation functionals and basis sets are chosen. The atomic structure is then optimized to reach the system’s lowest energy state, and the total energy and adsorption energy are calculated. Finally, the calculated adsorption energy is compared with experimental data to obtain the corresponding pore structure parameters. The SSA values for bulk shales at Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 are 29.910 m2/g, 36.752 m2/g, and 20.640 m2/g, respectively, while OM SSA values are 53.831 m2/g, 152.019 m2/g, and 105.208 m2/g. TM1 has the highest SSA among these Wells, followed by TX1 and FC1. The comparison between SSA from N2 and CO2 adsorption tests on bulk shales reveals that the SSA from CO2 sorption tests is significantly larger, indicating a substantial contribution of micropores to the overall SSA in shale. The average SSA of OM pores in all three Wells is greater than that of bulk shales. Organic mesopores account for 67% to 83% of the entire mesopore SSA, while organic micropores account for 67% to 82% of the entire micropore SSA.

The average mesopore volumes for bulk shales in Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 are calculated using the BJH model as follows: 0.022 cm3/g, 0.018 cm3/g, and 0.060 cm3/g, respectively. The average PV of OM pores is 0.078 cm3/g, 0.069 cm3/g, and 0.049 cm3/g. When calculated using the DFT model, the PV for bulk shales in Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 are 0.004 cm3/g, 0.019 cm3/g, and 0.007 cm3/g, while the average PV of OM pores are 0.017 cm3/g, 0.046 cm3/g, and 0.032 cm3/g, respectively. The Wells TM1 and FC1 have the largest average mesopore volumes calculated based on the BJH model, while the Wells TM1 has the largest average micropore volume calculated using the DFT model. Of the entire mesopore volume, organic mesopores account for 44–82%, and of the entire micropore volume, organic micropores account for 68–93%.

PSD curves

The PSD curves are computed using the DFT and BJH models, based on experimental data on N2 and CO2 adsorption, respectively. For pores with a diameter over 2 nm, the BJH model is typically utilized48,49, whereas the DFT model is employed for pores smaller than 2 nm50,51. Figure 8 illustrates the PSD obtained by the BJH method for bulk shales and organic mesopores across the Wells studied. For Well FC1, the PSD mainly ranges from 3.8 nm to 43.8 nm for bulk shales and from 3.4 to 30.2 nm for organic mesopores. For Well TM1, the corresponding ranges are 3.4–43.5 nm for bulk shales and from 3.4 nm to 29.6 nm for organic mesopores. Similarly, Well TX1 shows ranges from 3.4 nm to 32.1 nm for bulk shales and from 3.1 to 28.5 nm for organic mesopores. The presence of comparable peaks in the trends of bulk shales and organic mesopores indicates that organic mesopores significantly contribute to the overall mesopore volume. The PSD of bulk shales and organic micropores is computed using the DFT method. For Well FC1, the PSD mainly ranges from 0.3 to 1.47 nm and 0.3 to 1.47 nm, for Well TM1 ranges from 0.3 nm to 1.48 nm and 0.3 nm to 1.47 nm, and for Well TX1 ranges from 0.3 nm to 1.47 nm and 0.3 nm to 1.48 nm. Given the similarity of the peaks in the trends of variation of OM and bulk shales, it can be inferred that the primary source of micropores as a whole is organic micropores.

In conclusion, the PSD curves of bulk shales and OM show similar trends, indicating the feasibility of isolating organic pores from bulk shale. Firstly, the analysis of the CO2 PSD curves for all samples reveals multi-peak distributions across all samples, indicating a complex pore structure. Secondly, a comparison of the N2 adsorption PSD curves indicates that as pore size increases, dV/dD gradually decreases. Lastly, the mesopore PSD curves for the three Wells display similar or parallel patterns. Analysis of micropore PSD curves reveals that Wells FC1 and TM1 exhibit higher pore peak values compared to TX1, which may enhance gas storage capacity in these Wells.

Surface roughness and Young’s modulus of OM

By using AFM, we obtained micromechanical surface pore structure and micromechanical properties of OM parameters in the samples and analyzed their surface roughness. The Young’s modulus of OM and the three-dimensional surface roughness of Wells FC1, TX1, and TM1 are shown in Figs. 9, 10 and 11. The surface roughness parameters Ra, Rq, and the average Young’s modulus of OM are shown (Table 3). Wells FC1, TM1, and TX1 have average Ra values of 50.85 nm, 40.3 nm, and 30.25 nm, accordingly. The average Rq values are 65.9 nm, 51.8 nm, and 50.4 nm, and the average modulus values are 13.39 GPa, 15.54 GPa for Well FC1, 6.48 GPa, 7.75 GPa for Well TM1, and 8.19 GPa, 13.12 GPa for Well TX1. The thermal maturity ranges from 2.32% to 3.72%, and the Ro values for well FC1 are 3.65% and 3.72%, with maximum values of Young’s modulus for OM being 25 GPa and 28 GPa, respectively (Fig. 9a2, a4). For well TM1, Ro values are 2.32% and 2.40%, with maximum values of Young’s modulus for OM being 14 GPa and 16 GPa (Fig. 10b2, b4). In well TX1, Ro values are 2.57% and 2.85%, with maximum values of Young’s modulus for OM being 19 GPa and 23 GPa (Fig. 11c2, c4). Across the three Wells, the average Young’s modulus increased from 6.48 GPa to 15.54 GPa.

Discussion

Relationship between thermal maturity and pore structure of OM

When OM begins to dissolve, generates an increased number of hydrocarbons, leading to the formation of numerous pores. Consequently, the PV and SSA of the micropores have a positive relationship with the TOC content (wt.%), increasing the SSA and PV of the shale matrix (Fig. 12b,d). Furthermore, the SSA in OM is significantly higher than in bulk shale, suggesting that organic micropores primarily contribute to total micropores. However, there is no correlation between TOC and the PV and SSA of mesopores, as these may contain clay minerals and other mineral components (Fig. 12a,c). Thus, the thermal maturity of OM must be taken into account52,53.

Some OM pores are filled with bitumen, resulting in a reduction in pore volume. Consequently, with increasing thermal maturity, OM pores tend to compact and collapse. The PV and SSA of organic micropores show a positive relationship with TOC. Furthermore, Fig. 12 illustrates that the correlation between TOC content and the organic micropore PV and SSA is larger than that of mesopores, suggesting that TOC content has a more substantial impact on organic micropores compared to mesopores.

A gradual decrease in the organic PV and SSA is observed as OM solidifies and its Young’s modulus improves with thermal maturity. Consequently, the organic micropore PV and SSA show an inverse relationship with the RO (Fig. 13b,d), while the mesopore SSA and PV display no correlation with RO (Fig. 13a,c). The correlation between RO and the PV and SSA of organic micropores is stronger than that observed for mesopores (Fig. 13), indicating that RO has a more significant impact on the PV and SSA of micropores than on mesopores. Additionally, the relationships between the PV and SSA of organic mesopores with TOC and RO are not particularly significant (Figs. 12a,c, 13a,c), suggesting that the pore structure is influenced not only by organic geochemistry but also by the micromechanical properties of OM and the heterogeneity of shale.

Evolution of micromechanical properties of OM in the over-mature stage

Shape standards are instrumental in distinguishing between kerogen and solid bitumen, which constitute the majority of OM in the over-mature stage54, under microscopic observation, kerogen displays a finely laminated structure characterized by densely packed organic particles, which form alternating layers with clay mineral layers. In contrast, bitumen exhibits a more homogeneous structure with a tight bond between bitumen and mineral particles, and it lacks a distinct laminated structure55.

The Young’s modulus of kerogen increases with RO (Fig. 14), primarily due to alterations within the internal chemical structure of kerogen. The chemical structure formation of kerogen occurs in two distinct phases: the production of dry gas and the formation of condensate oil and wet gas56. During the condensate oil and wet gas development phase, there is a significant structural shift characterized by an increase in the proportions of bridging and aromatic carbons. Conversely, the structural changes during the dry gas generation phase are comparatively minor, marked by a slight increase in aromatic carbon and bridging carbon proportions57. With increasing thermal maturity, the internal C-H structure of kerogen decreases, while the level of aromaticity rises, leading to an increase in kerogen density. This transformation results in kerogen gradually converting into solid bitumen, thereby increasing the Young’s modulus and brittleness of OM58. Consequently, with increasing thermal maturity, the Young’s modulus of OM rises. Furthermore, a variety of factors, including the lithology of shale formations, the types of OM, and the expansion of OM pores, significantly influence the micromechanical properties of OM.

Relationship between micromechanical properties of OM and OM pore structure at the over-mature stage

The presence of OM pores in shale may be influenced by the micromechanical properties of OM. In the Woodford Shale (Ro = 0.5–6.36%), Young’s modulus values for kerogen with well-formed pores vary from 6 to 15 GPa, whereas those with less developed pores range from 1.9 to 2.2 GPa60. This evidence suggests that thermal maturity impacts both the pore structure and micromechanical properties of OM. As thermal maturity increases, residual kerogen and pyrobitumen gradually evolve towards a graphite structure, leading to an increase in the Young’s modulus of OM. This structural evolution causes brittle graphite fractures, which contribute to the collapse of internal OM pores. Therefore, there is a negative relationship between the SSA and PV of OM micro-mesopores and Young’s modulus values (Fig. 15a–f). During the immature to oil generation stages, crude oil derived from kerogen cracking blocks mineral and organic mesopores. However, at a high stage of maturity, the development trend of mesopores remains relatively constant. Thus, the relationship between the organic SSA of mesopores and Young’s modulus is weak (Fig. 15b), as is the relationship with PV of mesopores (Fig. 15d). Additionally, compared to mesopores, organic micropores are significantly more affected by changes in Young’s modulus.

Relationship between micromechanical properties of OM and pore structure of OM; (a, b) Relationship between the organic micropores, mesopores SSA, and Young’s modulus; (c, d) Relationship between the organic micropores, mesopores PV and Young’s modulus; (e, f) Relationship between the organic micro-mesopores SSA, PV, and Young’s modulus.

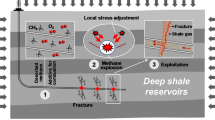

As thermal maturity increases, the absence of support from rigid mineral frameworks and pore fluid pressure results in the overlying strata or structural deformation compressing the organic pores, leading to pore compaction and a reduction in PV and SSA. This effect is particularly pronounced in shales with high clay mineral or OM enrichment, the plasticity of shale is increased, contributing to a decline in the number of OM pores and ultimately leading to their compaction and collapse. Concurrently, kerogen shape becomes more regular (Fig. 16). Additionally, brittle minerals, closely cemented with OM, exert pressure on the OM during diagenesis as thermal maturity increases61,62. With increasing thermal maturity, the organic micropores and mesopores are influenced by the rising of Young’s modulus of OM, evolving from regular circular and elliptical shapes to irregular shape distributions, and the number of OM pores gradually diminishes until the metamorphic stage (RO > 3.5%), when OM pores completely disappear and collapse21,63,64. The internal structures of OM micropores are particularly susceptible to collapse and compaction due to increased brittleness. In contrast, organic mesopores suffer significantly less damage during diagenesis compared to micropores owing to their larger pore size. The evolution of pore structures in shale reservoirs is critically influenced by the maturity of OM, its micromechanical properties, and interactions with brittle minerals, providing essential insights into the micromechanical mechanism of pore evolution in over-mature marine shale within complex structural regions.

Schematic of shale matrix pore evolution. (a) over-mature-deep, high-temperature stage (2.0% < RO < 2.5%), the number of organic pores increased a lot; (b) over-mature-deep, high-temperature stage later, the number of organic pores began to gradually decrease(2.5% < RO < 3.0%); (c)over-mature-metamorphic stage (3.0% < RO < 3.5%), the number of OM pores decreased rapidly, and the shape became irregular; (d) metamorphic stage (RO > 3.5%) due to OM is getting hard, which led to the OM pores gradually disappeared.

Conclusions

The characteristics of organic micropore and mesopore structures were investigated by collecting shale cores from the Niutitang Formation and conducting OM isolation and AFM tests. This study analyzes the influence of micromechanical properties on the characteristics of organic pore structures. The conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

-

(1)

In the over-mature stage, both bulk shale and organic pores predominantly develop elliptical, circular, or irregular shapes. The adsorption capacity of organic pores significantly surpasses that of bulk shale. Consequently, organic pores are the primary contributors to the PV and SSA of shale. Specifically, Organic micropores account for 68–93% and 67–82% of the total micropore PV and SSA, respectively. Similarly, organic mesopores account for 44–82% and 67–83% of the total mesopore PV and SSA, respectively.

-

(2)

In the over-mature stage, the micromechanical properties of OM increase with increasing thermal maturity. The OM Young’s modulus value increases due to the decrease in plasticity and increase in brittleness of OM. In this study, maturity increases from 2.32 to 3.72% and the average Young’s modulus increases from 6.48 to 15.54GPa.

-

(3)

As increasing thermal maturity, a negative correlation is observed between the micromechanical properties of OM and pore structure. The absence of a rigid mineral framework and pore fluid pressure leads to the compaction of organic pores, resulting in a decrease in PV and SSA. Given that mesopores are larger than micropores, the larger mesopores are more likely to remain in situ. Therefore, organic micropores are more susceptible to compaction and more strongly influenced by Young’s modulus values than mesopores.

Data availability

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

References

Dong, D. et al. Resource potential, exploration and development prospect of shale gas in the whole world. Geol. Bull. China 30(2–3), 324–336 (2011).

Guo, X. et al. Hydrocarbon generation and storage mechanisms of deep-water shelf shales of Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Silurian Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47(1), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1876-3804(20)60019-2 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. A primary discussion on challenges for exploration and development of shale gas resources in China. Nat. Gas Ind. 33(1), 8–17 (2013).

Wang, P. F. et al. Comparison of organic matter pores of marine and continental facies shale in China: Based on Focused Ion Beam Helium Ion Microscopy (FIB-HIM). Pet. Geol. Exp. 40(5), 739–748 (2018).

Wu, W. et al. Gas-in-place content of deep shales and its main controlling factors: A case study on the Wufeng-Longmaxi shales in the Middle Luzhou block of the Southern Sichuan Basin. China. Energy. Fuel. 37(12), 8296–8310. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c01220 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Depositional environment and thermal maturity of the coal-bearing Longtan shale in Southwest Guizhou, China: Implications for shale gas resource potential. Int. J. Coal Geol. 231, 103607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2020.103607 (2020).

Dong, D. Z. et al. Forming conditions and characteristics of shale gas in the Lower Paleozoic of the Upper Yangtze region. Oil Gas Geol. 31(3), 288–299 (2010).

Dong, D. Z. et al. Forming conditions and characteristics of shale gas in the Lower Paleozoic of the Upper Yangtze region. China 31(3), 288–299 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. Influencing mechanism of saline sediments on pore system formation and evolution in terrestrial shales. Petrol. Sci. 20(6), 3280–3300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2023.06.010 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. Organic geochemical characteristics, mineralogy, petrophysical properties, and shale gas prospects of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shales in Sanquan Town of the Nanchuan District Chongqing. Aapg Bull. 102(11), 2239–2265. https://doi.org/10.1306/04241817065 (2018).

İnan, S. et al. Formation and occurrence of organic matter-hosted porosity in shales. Int. J. Coal Geol. 199, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2018.09.021 (2018).

Ji, W. et al. Pore characterization of isolated organic matter from high matured gas shale reservoir. Int. J. Coal Geol. 174, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2017.03.005 (2017).

Liu, K. et al. Nanopore structures of isolated kerogen and bulk shale in Bakken Formation. Fuel 226, 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.04.034 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Evolution of mechanical properties of kerogen with thermal maturity. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 145, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105906 (2022).

Wang, Y., Liu, L. & Cheng, H. Gas adsorption characterization of pore structure of organic-rich shale: Insights into contribution of organic matter to shale pore network. Nat. Resour. Res. 30, 2377–2395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-021-09817-5 (2021).

Kuila, U. et al. Nano-scale texture and porosity of organic matter and clay minerals in organic-rich Mudrocks. Fuel 135, 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.06.036 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Effect of organic matter on pore structure of mature lacustrine organic-rich shale: A case study of the Triassic Yanchang shale, Ordos Basin China. Fuel 185, 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.100 (2016).

Safaei-Farouji, M. et al. Simulation of thermal maturity in kerogen type II using hydrous and anhydrous pyrolysis: A Case study from the Bakken Shale, United States. Energy. Fuel. 37, 19602–19620. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c02845 (2023).

Sun, M. et al. Pore structure characterization of organic-rich Niutitang shale from China: Small angle neutron scattering (SANS) study. Int. J. Coal Geol. 186, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2017.12.006 (2018).

Clarkson, C. R. et al. Characterization of tight gas reservoir pore structure using Usans/sans and gas adsorption analysis. Fuel 95, 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.12.010 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Maceral evolution of lacustrine shale and its effects on the development of organic pores during low mature to high mature stage: A case study from the Qingshankou Formation in northern Songliao Basin, northeast China. Petrol. Sci. 20(5), 2709–2725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2023.08.025 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Comparative study on pore structure characteristics of marine and transitional facies shales: A case study of the Upper Permian Longtan Formation and Dalong Formation in the Lower Yangtze area, south China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 215, 110578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110578 (2022).

Sun, W. et al. Pore structures of shale cores in different tectonic locations in the complex tectonic region: A case study of the Niutitang Formation in Northern Guizhou, Southwest China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 80, 103398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103398 (2020).

Sun, W. et al. The distribution characteristics of brittle minerals in the Lower Cambrian Niutitang Formation in northern Guizhou. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 86, 103752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103752 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Thermal maturity: The controlling factor of wettability, pore structure, and oil content in the lacustrine Qingshankou shale. Songliao Basin. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 215, 110618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110618 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. An experimental study of organic matter, minerals and porosity evolution in shales within high-temperature and high-pressure constraints. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 102, 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.12.014 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. Pore structure characterization for the Longmaxi and Niutitang shales in the Upper Yangtze Platform, South China: Evidence from focused Ion beam–he Ion microscopy, nano-computerized tomography and gas adsorption analysis. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 77(5), 1323–1337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.09.001 (2016).

Song, D. et al. A comprehensive study on the impacts of rock fabric on hydrocarbon generation and pore structure evolution of shale under semi-confined condition. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 124, 104830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104830 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Pore system and gas adsorption potential of lacustrine Yanchang Mudstone, Ordos Basin. China. Energy Rep. 8, 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.11.259 (2022).

Gu, Y. et al. Microstructure evolution of organic matter and clay minerals in shales with increasing thermal maturity. Acta Geol. Sin.-English Edition. 94(2), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-6724.14285 (2020).

Eliyahu, M. et al. Mechanical properties of organic matter in shales mapped at the nanometer scale. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 59, 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2014.09.007 (2015).

Graham, S. P. et al. Geomechanical characterisation of organic-rich calcareous shale using AFM and nanoindentation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54(1), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02261-6 (2021).

Kong, L. et al. AFM vs. Nanoindentation: Nanomechanical properties of organic-rich Shale. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 132, 105229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.105229 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Influence of geochemical features on the mechanical properties of organic matter in shale. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth. 125(9), e2020JB019809. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020jb019809 (2020).

Sun, W. et al. Impact of tectonic deformation on shale pore structure using adsorption experiments and 3D digital core observation: A case study of the Niutitang Formation in Northern Guizhou. Energy 278, 127724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127724 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Characteristics and dominant controlling factors of organic-rich marine shales with high thermal maturity: a case study of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang Formation in the Cen, Gong block, southern China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 33, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.05.009 (2016).

Zheng, W. et al. Analyses of the characteristics and main controlling factors for the micro/nanopores in Niutitang shale from China’s southeastern Chongqing and Northern Guizhou regions. Earth Sci. Front. 26, 220 (2019).

He, X. et al. The study on the Qian Zhong upheaval. Guizhou Geol. 22, 83–89 (2002).

Yang, C. et al. Reservoir characteristics and exploration potential evaluation of lower Cambrian Niutitang Shale in Northern Guizhou: A case study of well Qx1. Energies 17, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17051166 (2024).

Jacob, H. Classification, structure, genesis and practical importance of natural solid oil bitumen (“migrabitumen”). Int. J. Coal Geol. 11(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-5162(89)90113-4 (1989).

Brunauer, S., Emmett, P. H. & Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 60(2), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2509(75)85027-5 (1938).

Do, D. D. & Do, H. D. Pore characterization of carbonaceous materials by DFT and GCMC simulations: A review. Adsorp. Sci. Technol. 21(5), 389–423. https://doi.org/10.1260/026361703769645753 (2003).

Barrett, E. P., Joyner, L. G. & Halenda, P. P. The determination of pore volume and area distributions in porous substances. I. Computations from nitrogen isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73(1), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01145a126 (1951).

Li, C. et al. Application of PeakForce tapping mode of atomic force microscope to characterize nanomechanical properties of organic matter of the Bakken Shale. Fuel 233, 894–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.021 (2018).

Yang, R. et al. Nano-scale pore structure and fractal dimension of organic-rich Wufeng-Longmaxi shale from Jiaoshiba area, Sichuan Basin: Investigations using FE-SEM, gas adsorption and helium pycnometry. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 70, 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.11.019 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Porosity changes in progressively pulverized anthracite subsamples: Implications for the study of closed pore distribution in coals. Fuel 225, 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2509(75)85027-5 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Compositional shift of residual gas during desorption from anthracite and its influencing factors. Fuel 250, 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.03.144 (2019).

Algazlan, M. et al. Role of organic matter and pore structure on CO2 adsorption of Australian organic-rich shales. Energy. Fuel. 36, 5695–5708. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c00657 (2022).

Cui, R. et al. Pore structure and gas adsorption characteristics in stress-loaded shale on molecular simulation. Energy. 286, 129658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129658 (2024).

Xiong, J. et al. Insights into the pore structure characteristics of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation shale in the Jiaoshiba area, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 12(10), 2857–2868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-022-01486-1 (2022).

Zou, J., Rezaee, R. & Liu, K. Effect of temperature on methane adsorption in shale gas reservoirs. Energy. Fuel. 31(11), 12081–12092. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02639 (2017).

Song, L. & Carr, T. R. The pore structural evolution of the Marcellus and Mahantango shales. Appalachian Basin. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 114, 104226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104226 (2020).

Xie, W. et al. Effects of gas components, reservoir property and pore structure of shale gas reservoir on the competitive adsorption behavior of CO2 and CH4. Energy 254, 124242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124242 (2022).

Liu, B., Mastalerz, M. & Schieber, J. SEM petrography of dispersed organic matter in black shales: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 224, 103874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103874 (2022).

Emmanuel, S. et al. Impact of thermal maturation on nano-scale elastic properties of organic matter in shales. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 70, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.12.001 (2016).

Liu, Y., Xiong, Y. & Li, Y. Effect of thermal maturation on chemical structure and nanomechanical properties of solid bitumen. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 92, 780–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.12.008 (2018).

Zheng, T. et al. Kerogen structure and porosity in Woodford Shale before and after hydrous closed-system pyrolysis. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 145, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2023.104375 (2022).

Okiongbo, K. S., Aplin, A. C. & Larter, S. R. Changes in type II kerogen density as a function of maturity: Evidence from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation. Energy. Fuel. 19(6), 2495–2499. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef050194 (2005).

Kumar, V. et al. Estimation of elastic properties of organic matter and woodford shale through nano-indentation measurements. SPE Canada Unconventional Resources Conference? SPE, 2012:162778. SPE-162778-MS.

Liu, Y., Su, C. & Shang, F. Direct imaging of micropores in shale kerogen. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 146, 105928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105928 (2022).

Tan, J. et al. Pore evolution of lacustrine organic-rich shales: insights from thermal simulation experiments. Energy. Fuel 35, 3079–3094. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c03828 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Organic matter pores structure and evolution in shales based on the he ion microscopy (HIM): A case study from the Triassic Yanchang, Lower Silurian Longmaxi and Lower Cambrian Niutitang shales in China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 84, 103682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103682 (2020).

Hu, C. et al. Evolution of organic pores in Permian low maturity shales from the Dalong formation in the Sichuan Basin: Insights from a thermal simulation. Gas Sci. Eng. 121, 205166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2023.205166 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. New insights into controlling factors of pore evolution in organic-rich shale. Energy Fuel 35(6), 4858–4873. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c04189 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Nos. 52264004, 51774101, 52104080, and 52164016); the Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (Project No. Qiankehe Basic-ZK [2024] General 050); the Guizhou University Natural Science Special (Special Post) Scientific Research Fund Project (Project No. (2021) 51) and the Guizhou Outstanding Young Science and Technology Talent Program (YQK [2023]012). The authors gratefully acknowledge this assistance

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Declarations Investigation and Writing –original draft, H.L.; Resources, Funding acquisition, and Writing – editing W.S.; Supervision and Resources, Y.Z.; Visualization and Investigation, Z.W.; Visualization Q.D.; Software, W. L.; Validation, Y.L.; Supervision, X.X.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, H., Sun, W., Zuo, Y. et al. Impact of micromechanical properties of organic matter on the micro-mesopore structures of the over-mature shale in the Niutitang Formation. Sci Rep 15, 4542 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89164-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89164-0