Abstract

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is the most common respiratory complication after preterm birth. Early preventive measures are important to reduce further damage on lung tissue. Thus, early discrimination between infants with and without BPD is of high importance. A low sample entropy (SampEn) of time series of the oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2-SampEn for short) is associated with an increased risk of hypoxemic events in neonates. We hypothesized that preterm infants have a lower SpO2-SampEn compared to term infants. Moreover, that infants with BPD have a lower SpO2-SampEn compared to those without BPD. Preterm infants < 32 w gestation and healthy term infants were eligible for study. We recorded SpO2 over 90 min through the clinical monitoring system with a sampling frequency of 0.98 Hz and calculated the SpO2-SampEn at 32 w postmenstrual age (PMA), 36 w PMA, and at discharge. We included 95 term and 180 preterm infants, of whom 44 (24.4%) developed BPD. SpO2-SampEn was lower in preterm infants compared to term infants. SpO2-SampEn was lower in infants with BPD compared to infants without BPD at 32 w PMA. However, gestational age was the only predictor of SampEn at 32 w PMA. This difference between infants with and without BPD was no longer present at 36 w PMA and discharge. SpO2-SampEn can be utilized to discriminate between preterm and term infants and between preterm infants with and without BPD. However, confounding factors such as caffeine therapy, gestational age and the natural boundary of 100% of SpO2 values have to be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary and cardiovascular development and function are closely linked during fetal development and postnatal life1. In newborn infants, the interaction between the pulmonary and cardiovascular system plays an important role during transition after birth. However, in preterm infants normal development of the pulmonary and cardiac systems is interrupted, which results in delayed cardiopulmonary adaptation and potentially to delayed long-term development of these systems2. The most common long term respiratory complication after preterm birth is bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). BPD affects between five to 30% of all very preterm infants (< 32 w gestation) and its prevalence is increasing due to increased survival rates of extremely preterm infants born at the limits of viability3,4. Evolving BPD is considered a developmental disease of the lung structure, resulting in ventilation-perfusion mismatch, clinically characterized by frequent intermittent hypoxia, prolonged requirement of respiratory support and supplemental oxygen to maintain stable oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2)2,5. In addition to structural immaturity of the lung, preterm infants exhibit an immature cardiopulmonary autonomous nervous system2,6,7. Preterm infants typically show irregular breathing and frequently have apnea of prematurity, associated with unstable SpO2, hypoxemia and bradycardia during the first weeks to months of life8.

Maturation of the cardiac autonomous nervous system is associated with an increased parasympathetic activity and can be quantitatively assessed using the heart rate variability (HRV). HRV increases as the parasympathetic activity increases, which explains the lower HRV in preterm infants compared to term infants6,9. Further, the mathematical analysis of HR time series can be used to assess the predictive value of the HR for clinically important events or medium-term clinical outcomes in neonates. For instance, the sample entropy (SampEn) of HR time series, a parameter describing complexity of values within a time series of heart beats, can be used as an early marker of neonatal sepsis10 and as a predictor of stability of the respiratory system in preterm infants over several months11. SampEn decreases not only when physiological data is highly regular but also in the presence of spikes/decelerations, or both12. Such phenomena are typical in time series analyses of physiological signals in preterm infants. The SampEn can not only be calculated from HR but also from time series of other physiological signals such as SpO2, provided the time series are sufficiently long and have been sampled at a frequency corresponding to the natural time scales of the physiological processes involved. In critically ill adults with sepsis, lower SampEn of SpO2 was a predictor of mortality13. Given the impact of immaturity and BPD on SpO2 stability and the predictive value of SampEn of HR on outcomes in preterm neonates, SampEn of time series of SpO2 may offer diagnostic value in this population. E.g., SampEn of SpO2 time series might be associated with maturational processes and respiratory disease in preterm infants. We would expect SampEn of SpO2 to increase with postnatal maturation and with resolution of lung disease due to less frequent hypoxemic events. Therefore, substantial differences in SampEn between infants with and without BPD might enable an earlier diagnosis of BPD by defining a SampEn threshold.

We aimed to investigate the SampEn of time series of SpO2 in preterm compared to term infants. Moreover, we aimed to compare the SampEn of SpO2 in preterm infants with and without BPD across several time points during their hospitalization after birth. We then aimed to identify demographic and respiratory disease related factors associated with SampEn of SpO2 at the different time points. This study also evaluates the technical feasibility and validity of the SampEn of SpO2 in a clinical setting. We hypothesized that SampEn of SpO2 is lower in preterm infants compared to term infants, and that the presence of BPD is associated with lower SampEn among preterm infants. Secondary outcomes include the variability in SpO2 of infants with BPD through calculation of the mean, the standard deviation (SD) and the coefficient of variation (CV).

Results

Demographic data

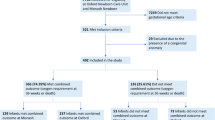

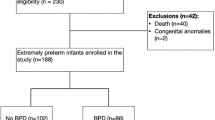

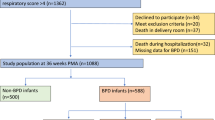

We included a total of 275 infants in this study. Of these, 180 were preterm infants and 95 term healthy infants. Forty-four of the 180 preterm infants (24.4%) were subsequently diagnosed with BPD (Fig. 1). Anthropometric data are outlined in Table 1. Gestational age, birth weight, and length at birth of infants with BPD were lower compared to infants without BPD. All preterm infants received caffeine during hospitalization. Caffeine administration was stopped later in preterm infants with BPD (caffeine administration at 36 w PMA in 80% of BPD infants vs. 20% of infants without BPD). Duration of supplemental oxygen and duration of respiratory support were longer in infants with BPD compared to those without BPD (Table 2).

Sample entropy

The durations and effective durations of all SpO2 time series obtained at 32 w PMA, 36 w PMA, and at discharge are outlined in Table 3. Total duration refers to the whole measurement, whereas the effective duration is the duration of the longest uninterrupted interval in the time series, i.e., the longest interval containing no missing values/artefacts. On average, the effective duration was > 5400 s at 36 weeks PMA and at discharge. The average effective duration was 4958 s at 32 weeks PMA due to difficulties obtaining uninterrupted measurements in preterm infants with BPD.

Overall, the SampEn of SpO2 in preterm infants at discharge was lower than that in term healthy infants (0.18 (0.10) vs. 0.22 (0.11), p < 0.05). Infants with BPD had a significantly lower mean (SD) SampEn compared to infants without BPD at 32 w PMA (0.19 (0.08) vs. 0.26 (0.09); p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). However, the difference in SampEn was no longer present at 36 w PMA and at discharge. In preterm infants without BPD, SampEn decreased from 32 w PMA to 36 w PMA (0.26 (0.09) vs. 0.16 (0.12), p < 0.001), but not from 36 w PMA to discharge (0.16 (0.12) vs. 0.17 (0.12), p 0.75). Infants with BPD had significantly lower SampEn of SpO2 compared to term infants at discharge (Fig. 2). Example waveforms of SpO2 time series are shown in Fig. 3.

We identified gestational age, postnatal age, birthweight z-score, the diagnosis of BPD, days on oxygen, days on conventional mechanical ventilation, days on NIPPV (non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation) and days on HHHF (heated humidified high flow) and caffeine at the time of measurement as potential explanatory factors for SampEn of SpO2 at 32 and 36 w PMA and at discharge. Gestational age as an indicator of maturation is more important than postnatal age in preterm infants. Therefore, we omitted postnatal age due to collinearity with gestational age in the final model (R2 = 0.99). Moreover, variables related to respiratory support were collinear with gestational age. Therefore, we computed the unstandardized residual for days on oxygen, conventional mechanical ventilation, days on NIPPV and days on HHHF against gestational age prior to the univariate analysis. We used the unstandardized residuals as independent measures of respiratory support.

Gestational age was the only statistically significant predictor of SampEn of SpO2 at 32 w PMA. Gestational age explained 17.8% of the variability seen in SampEn of SpO2 at 32 w PMA (adjusted R2 = 0.178, p < 0.001). Days on NIPPV independent of gestational age was the only predictor of SampEn of SpO2 at 36 w PMA and explained 4% of the variability (adjusted R2 = 0.039, p < 0.001). At discharge none of the entered variables were statistically significantly associated with SampEn of SpO2.

Additional measures of variability

We evaluated the mean, SD, and CV of SpO2 time series as measures of central tendency and dispersion in the time series (Table 4). SD and CV of SpO2 in preterm infants was higher compared to term infants. In infants with BPD, SpO2 time series had statistically significantly lower mean and higher SD and CV compared to infants without BPD at all three time points. Mean SpO2 increased in all preterm infants over time. Also, SD and CV of SpO2 decreased over time in infants with and without BPD, with still significantly higher SD and CV in infants with BPD vs. infants without BPD at discharge.

Discussion

We found that SampEn of time series of SpO2 was lower in preterm infants compared to term healthy infants at discharge. SampEn of SpO2 was lower in preterm infants with BPD compared to infants without BPD at 32 w PMA. However, the main predictor of SampEn of SpO2 at 32 w PMA is maturation at birth. The difference in SampEn of SpO2 between infants with and without BPD was no longer present at 36 w PMA or at discharge. NIPPV was a significant predictor of SampEn of SpO2 at 36 w PMA but explained only 4% of the variability of SampEn of SpO2. Longitudinally, SampEn of SpO2 in preterm infants with BPD did not substantially change from 32 w PMA to discharge while there was a marked decrease in preterm infants without BPD from 32 to 36 w PMA (but not from 36 w PMA to discharge). As expected, conventional measures of dispersion including SD and CV of SpO2 in preterm infants at discharge were higher compared to term infants. In preterm infants with BPD, time series of SpO2 had higher SD and CV than those without BPD across all time points.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing SampEn of SpO2 in preterm vs. term infants and, longitudinally, in preterm infants with and without BPD over the course of weeks to months. Recent studies in adults indicate that SampEn of SpO2 is a good predictor of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and of survival in critically ill patients with sepsis13,14. Small studies in neonates (n = 25–44) showed that low SampEn of SpO2 is associated with a higher risk of intermittent hypoxemic events in the NICU and an important predictor of periventricular leukomalacia following neonatal heart surgery15,16. There are no published studies assessing the association of SampEn of SpO2 with neonatal respiratory disease or with postnatal maturation in preterm neonates. However, low SampEn of time series of HR was previously identified as an indicator of extubation failure and of poor postnatal maturation in preterm infants17,18.

We expected SampEn of SpO2 to be lower in preterm infants with BPD compared to infants without BPD. Furthermore, we expected an increase in SampEn of SpO2 towards discharge, potentially approaching values of healthy term infants, i.e., to reflect both resolution of respiratory disease and postnatal maturation of lung structure and autonomous nervous system. We found that SampEn of SpO2 in preterm infants with BPD was lower at 32 w PMA compared to infants without BPD, but the main predictor of SampEn of SpO2 at 32 w PMA is maturation at birth. Nevertheless, values remained stable until discharge in infants with BPD and decreased significantly in those without BPD from 32 to 36 w PMA (but not from 36 w PMA towards discharge). A decrease in SampEn of SpO2 in infants without BPD over several weeks seems counterintuitive. However, the effect of important co-factors may explain this finding: Almost all preterm infants were prescribed caffeine at 32 w PMA, independent of BPD status (170 of 171 infants). In contrast, 80% of infants with BPD but only 20% of infants without BPD still received caffeine at 36 w PMA which may have resulted in an increased frequency of short hypoxemic events in the former, leading to lower SampEn of SpO2 after cessation of caffeine. Caffeine citrate is a highly effective treatment for apnea of prematurity and prevention of BPD19. The discrepancy in rates of caffeine administration at 36 w PMA is a result of clinical practice as physicians typically discontinue caffeine upon increasing cardiorespiratory stability of patients which occurs earlier in those infants who do not develop BPD. In previous studies, caffeine administration induced an enhanced autonomic nervous system responsiveness, reflected by indices of parasympathetic activity from HR and blood pressure systems20. Thus, the decrease of SampEn in time series of SpO2 from 32 to 36 w PMA in infants without BPD may be related to earlier discontinuation of caffeine administration, resulting in values comparable to those of infants with BPD who remained on caffeine. As a result, caffeine therapy is not statistically significantly associated with SampEn of SpO2 at 36 w PMA. Also, with increasing age and improving lung maturation, preterm infants without BPD will tend to show SpO2 values close to 100% for extended periods of time. Due to this ceiling effect, SampEn of SpO2 may decrease as the time series may become highly regular. SampEn may potentially even approach lower values than that of ‘less stable’ appearing time series (Fig. 3b), which might also explain the longitudinal decrease in SampEn in preterm infants without BPD from 32 to 36 w PMA. The persistently low SampEn of time series of SpO2 in infants with BPD at 36 w PMA may be explained by ongoing respiratory disease. At discharge, SampEn of SpO2 did not differ between preterm infants with and without BPD. Importantly, the average PMA at discharge in preterm infants with BPD was 40 w PMA but only 37 w PMA in those without BPD. Given that the SampEn of a cardiorespiratory signal in infants may be interpreted as an integrative physiological marker of health12, the 3-week advantage in maturation to overcome residual respiratory disease may explain this finding. Overall, values in preterm infants at discharge were lower than those of healthy term infants which may reflect differences in maturation as the mean PMA at discharge in the whole cohort of preterm infants was 37.4 w vs. 40.3 w in healthy term infants. Even though healthy term infants were on average three weeks older at discharge compared to the preterm infants included in our study (40 w PMA compared to 37 w PMA), healthy term infants seem to be the only suitable control group of infants for our discharge measurements. Healthy term infants are ready for discharge within hours to days after birth as they are mature enough and maintain a stable SpO2. Thus, important factors to consider when evaluating SampEn of SpO2 in infants with and without BPD over various timepoints are gestational age, caffeine administration and the ceiling effect of SpO2 values.

In terms of secondary outcome measures, we found an increased variability in SpO2 as measured by the SD and CV of SpO2 in preterm infants with BPD compared to preterm infants without BPD and term healthy infants, potentially reflecting the lack of stability of oxygenation in infants with BPD. This seems biologically plausible and suggests that conventional measures of variation of a set of values, such as SD and CV, are not necessarily aligned with measures of complexity derived from nonlinear time series analysis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating SampEn of SpO2 in preterm infants with and without BPD and comparing them with term healthy infants in a pragmatic clinical care setting. Our study was prospectively designed and included a total of 275 infants, ensuring sufficient statistical power to evaluate and interpret results. Also, the aimed-for duration of the time series was 90 min, resulting in about 5000 data points per measurement which is safely above the 2000 data points where entropy values seem to stabilize21,22. Further, the use of the SpO2 signal derived from peripheral pulse oximeters instead of the HR from electrocardiogram allows for application and repetition of such an analysis in clinical study settings beyond intensive care, as pulse oximeters are commonly available in normal wards and even outpatient areas.

Our study has some limitations that require careful interpretation of the results. Although we included preterm infants from 23 to 32 w gestation, only 44/180 preterm infants had BPD due to the relatively low rate of BPD among infants at our hospital. This may result in spectrum bias. Along with the single-center design, this limits generalizability of the results, particularly since respiratory care practices and incidences of BPD vary widely among hospitals and countries23. We corrected for differences between extrauterine maturation in infants with and without BPD by assessing SampEn of SpO2 at a common PMA. However, BPD is an evolving disease and extrauterine development might be affected by several factors such as preexisting disease, nutritional management, or intercurrent infections. Nevertheless, assessment at a common PMA seems a reasonable approach to correct for extrauterine maturation. There are multiple potential technical and clinical confounders that need to be considered. Restlessness can affect the artefact-free pulse oximetry measurement. By measuring the infants 30 min after a morning feed in a sleeping or quiet awake state, we aimed to minimize these artefacts on the pulse oximetry measurements. Also, clinical confounders like sepsis, inotrope use, and caffeine citrate can affect SampEn data10. Therefore, we assessed for any relevant medication during measurements. Almost all infants received caffeine at 32 w PMA (n = 170/171). At 36 w 80% of infants with BPD and 20% of infants without BPD still received caffeine. However, at 36 PMA, caffeine therapy was not associated with SampEn of SpO2. At 32 w, 5 infants received antibiotic treatment, of which 1 infant (20%) had BPD and died. One infant had already received antibiotic treatment for 14 days and thus did not have an acute infection. At 36 w, one infant without BPD received antibiotics. No inotrope use was documented during any of the measurements. Due to the low number of infants (3%) that received antibiotic treatment, we do not expect there to be a relevant impact on our results. Further, although calculations of SampEn of SpO2 were readily available within minutes after the measurements, they were not available as continuous outputs that could directly be used by clinicians in the NICU which limits clinical utility in routine preterm care. Furthermore, when assessing SampEn of SpO2 time series the underlying algorithm of SpO2 signal processing might differ dependent on the manufacturer thereby affecting the results24.

Given the widespread use and multitude of effects of caffeine on the cardiorespiratory system in preterm infants25, it seems imminent to assess its effects on parameters of nonlinear time series analyses. Particularly when considering that nonlinear time series analyses may soon be implemented in clinical care and integrated into NICU monitoring systems26. Further, we measured SampEn of SpO2 in a clearly defined cohort of preterm infants and a control group of healthy term infants to assess the diagnostic utility related to BPD and postnatal maturation. Arguably, the relative importance of intermittent hypoxic events and a ceiling effect of SpO2 values at 100%, development of reference values and the use of standardized methods for signal acquisition, data processing, and interpretation would allow for comparison across different physiological signals, patient populations, and study settings. Nonlinear time series analysis in preterm infants is possible in a variety of physiological signals such as HR, respiratory rate, SpO2, or body temperature11,12,15,17,27. If and how SampEn estimations correlate across several physiological signals, whether any potential correlations depend on the time scale of measurement, and how they may complement each other to improve diagnostic utility for early detection of disease or monitoring of maturation in preterm infants remains to be investigated in future studies.

SampEn of time series of SpO2 can be utilized to discriminate between preterm infants with and without BPD and preterm vs. healthy term infants but requires careful consideration of confounding factors such as maturation at birth and the natural boundary of 100% of SpO2 values. In contrast, standard measures of variation such as mean, standard deviation and coefficient of variation of SpO2 seem less dependent on confounding factors. The potential of SpO2-SampEn for monitoring postnatal maturation and its relation to other physiological signals suitable for nonlinear time series analysis requires further study. Also, after the initial validation phase, more clinical studies need to be conducted to validate the clinical utility of SpO2-SampEn for early prediction of adverse neonatal outcomes.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a single center observational cohort study at the University Children’s Hospital Basel (UKBB) in Switzerland between December 2018 and July 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ, Ref 2018-01,207). All measurements were performed in accordance with the regulations of the ethics committee. Written parental consent was obtained for all participants prior to study enrolment. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04303494).

Participants

This study is a subproject within the larger study Predictive Value of Heart Rate Variability on Cardiorespiratory Events (NCT04303494). Very preterm infants (< 32 w gestation) and/or those with a birth weight less than 1500 g were eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria for term healthy control infants were (1) chronological age of 3 to 28 days, and (2) hospitalization in the neonatal rooming-in unit as a healthy sibling, or a healthy neonate ready for discharge from the maternity ward. Exclusion criteria included major congenital malformations including neuromuscular disorders, thoracic malformations, or a major cardiac malformation. Eligible infants were allocated into groups according to whether they were born preterm or at term and the presence of a BPD diagnosis according to the NICHD BPD definition published in 20011.

Clinical variables and measurements

We obtained sex, gestational age, birth weight and length at birth from medical records. Body weight was recorded at each test occasion. We measured SpO2 over a 90-min period at 32 w postmenstrual age (PMA), 36 w PMA and at discharge. To rule out the effects of night/day cycling, spontaneous movements, feeding, and nursing care procedures on SpO2, we aimed to start SampEn recordings at 9 am while infants were asleep, or at least in a quiet awake state 30 min after a morning feed. Consequently, if above conditions could not be met after the morning feed, the next feasible observation period after an 11 am feed was chosen. SpO2 was measured via pulse oximetry using the standard neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) monitoring system (Philips IntelliVue MX700, Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands). FiO2 management was based on standard operating procedures and overseen by nurses at the bedside and adapted to achieve an SpO2 range of 87–95% in infants with supplemental oxygen and 87–100% in infants without supplemental oxygen. Raw data was acquired at 0.98 Hz and processed by a commercially available software (ixTrend and Dataplore, ixcellence GmbH, Wildau, Germany). All clinical data was stored in a LabKey database installed on a local server. LabKey is an open-source platform for scientific data integration, analysis, and collaboration28. SampEn for time series of SpO2 measurements was calculated based on the analysis, insights and recommendations outlined by Richman and Moorman21, using custom-made software implemented in R29 and using the following R-Packages: “TSEntropies”30, “lubridate”31 “dplyr”32, “FSA”33, "data.table"34, “Rlabkey”35, “mgsub”36. For the calculation of the SampEn using the algorithm implemented within the R-package “TSEntropies”, the following parameters were used: Embedding dimension m = 3, radius of searched areas r = 0.2*sd(TS), where sd(TS) stands for the standard deviation of the whole time series at hand. No downsampling was used, i.e., the lag parameter was set equal to 1. Furthermore, for the ease of use for our study staff, our R-code was integrated in a graphical user interface (GUI) using the Shiny Framework37,38,39. SampEn is the “negative natural logarithm of the conditional probability that two sequences similar for m points remain similar at the next point”, without allowing self-matches21. Thus, SampEn is a measure of randomness of a time series. In other words, SampEn represents the rate at which new information is produced in a time series. Low SampEn indicates lower complexity within a time series, i.e., less information production. Typically, reduced SampEn of HR time series is associated with short- or medium-term disease in neonates10,11,21,40. Based on previous work by Richman and Moorman21, our goal was to collect time series of SpO2 containing at least 4096 values measured equidistantly in time, which corresponds to measuring uninterruptedly for 69.66 min at a sampling frequency of 0.98 Hz. Thus, and in order to leave a margin, we obtained each time series by measuring for 90 min. However, due to movement artefacts during some measurements, the resulting time series occasionally contained missing values or invalid values. Consequently, we searched in each time series for the longest uninterrupted interval. The duration of this interval is what we called the effective duration of the time series. Oftentimes the effective duration was longer or equal to 69.66 min, i.e., the minimum duration required according to Richman and Moorman. In the few cases in which the effective duration was shorter, we increased the effective duration by imputing missing values/artefacts. Imputation was done using Spline interpolation as implemented in the R-package “imputeTS”41. In such cases, only time series with less than 3% missing values were used.

Statistical methods

We tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk’s method combined with visual inspection through Q–Q plots and testing for absence of variance through the F-test. We used mean, SD and the independent two-tailed t-test for normally distributed data and median, interquartile range (IQR) and the Mann–Whitney U test (Wilcoxon test) for non-normally distributed data. Linear regression analysis was used to assess potential explanatory variables of SampEn of SpO2 at the time points 32- and 36-weeks postmenstrual age as well as at discharge. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software R (version 4.0.3, R Development Core Team, Vienna Austria)29 and figures were produced using the package ggplot242. Missing values were analyzed through available case analysis. Aiming for 80% power at a 5% significance level, assuming that prematurity status and BPD have a small effect size (f2 = 0.26)43, we planned to analyze data from a sample of n = 180 preterm infants and n = 100 term infants.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jobe, A. H. & Bancalari, E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163, 1723–1729. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060 (2001).

Yallapragada, S. G., Savani, R. C. & Goss, K. N. Cardiovascular impact and sequelae of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 56, 3453–3463. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25370 (2021).

Thébaud, B. et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Nature Rev. Dis. Primers 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0127-7 (2019).

Geetha, O. et al. New BPD-prevalence and risk factors for bronchopulmonary dysplasia/mortality in extremely low gestational age infants ≤28 weeks. J. Perinatol. 41, 1943–1950. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01095-6 (2021).

Jensen, E. A. et al. Association between intermittent hypoxemia and severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 204, 1192–1199. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202105-1150OC (2021).

Longin, E., Gerstner, T., Schaible, T., Lenz, T. & König, S. Maturation of the autonomic nervous system: differences in heart rate variability in premature vs. term infants. J. Perinat. Med. 34, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2006.058 (2006).

Harteveld, L. M. et al. Maturation of the cardiac autonomic nervous system activity in children and adolescents. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e017405. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.120.017405 (2021).

Di Fiore, J. M., Poets, C. F., Gauda, E., Martin, R. J. & MacFarlane, P. Cardiorespiratory events in preterm infants: Etiology and monitoring technologies. J. Perinatol. 36, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.164 (2016).

Lavanga, M. et al. Maturation of the autonomic nervous system in premature infants: Estimating development based on heart-rate variability analysis. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.581250 (2021).

Griffin, M. P. & Moorman, J. R. Toward the early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis and sepsis-like illness using novel heart rate analysis. Pediatrics 107, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.1.97 (2001).

Jost, K., Datta, A. N., Frey, U. P., Suki, B. & Schulzke, S. M. Heart rate fluctuation after birth predicts subsequent cardiorespiratory stability in preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 86, 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0424-6 (2019).

Lake, D. E., Richman, J. S., Griffin, M. P. & Moormann, J. R. Sample entropy analysis of neonatal heart rate variability. Am. J. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00069.2002 (2002).

Gheorghita, M. et al. Reduced oxygen saturation entropy is associated with poor prognosis in critically ill patients with sepsis. Physiol. Rep. 10, e15546. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.15546 (2022).

Al Rajeh, A. et al. Application of oxygen saturation variability analysis for the detection of exacerbation in individuals with COPD: A proof-of-concept study. Physiol. Rep. 9, e15132. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.15132 (2021).

Ramanand, P., Indic, P., Travers, C. P. & Ambalavanan, N. Comparison of oxygen supplementation in very preterm infants: Variations of oxygen saturation features and their application to hypoxemic episode based risk stratification. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1016197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1016197 (2023).

Jalali, A., Licht, D. J. & Nataraj, C. Discovering hidden relationships in physiological signals for prediction of periventricular leukomalacia. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2013, 7080–7083. https://doi.org/10.1109/embc.2013.6611189 (2013).

Latremouille, S., Bhuller, M., Shalish, W. & Sant’Anna, G. Cardiorespiratory measures shortly after extubation and extubation outcomes in extremely preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 93, 1687–1693. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02284-5 (2023).

Stålhammar, A. M. et al. Weight a minute: The smaller and more immature, the more predictable the autonomic regulation?. Acta Paediatr. 112, 1443–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16796 (2023).

Schmidt, B. et al. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2112–2121. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa054065 (2006).

Huvanandana, J., Thamrin, C., McEwan, A. L., Hinder, M. & Tracy, M. B. Cardiovascular impact of intravenous caffeine in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 108, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14382 (2019).

Richman, J. S. & Moorman, J. R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H2039-2049. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039 (2000).

Yentes, J. M. et al. The appropriate use of approximate entropy and sample entropy with short data sets. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 41, 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-012-0668-3 (2013).

Siffel, C., Kistler, K. D., Lewis, J. F. M. & Sarda, S. P. Global incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia among extremely preterm infants: A systematic literature review. J. Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med. 34, 1721–1731. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1646240 (2021).

Johnston, E. D. et al. Oxygen targeting in preterm infants using the Masimo SET radical pulse oximeter. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 96, F429-433. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2010.206011 (2011).

Mitchell, L. & MacFarlane, P. M. Mechanistic actions of oxygen and methylxanthines on respiratory neural control and for the treatment of neonatal apnea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 273, 103318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2019.103318 (2020).

Van Laere, D. et al. Machine learning to support hemodynamic intervention in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin. Perinatol. 47, 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2020.05.002 (2020).

Jost, K. et al. Dynamics and complexity of body temperature in preterm infants nursed in incubators. PLoS One 12, e0176670. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176670 (2017).

Nelson, E. K. et al. LabKey Server: An open source platform for scientific data integration, analysis and collaboration. BMC Bioinform. 12, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-71 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, (Vienna, Austria, 2020). https://www.R-project.org/

Tomcala, J. TSEntropies: Time Series Entropies, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=TSEntropies (2018).

Garrett Grolemund, H. W. Dates and times made easy with lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 40, 1–25 (2011).

Wickham, H., Henry, L., Müller, K., Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (2023).

Ogle, D. H., Wheeler, A. P., Dinno, A. FSA: Simple Fisheries Stock Assessment Methods, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FSA (2023).

Dowle, M. A. S. data.table: Extension of data.frame, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=data.table (2023).

Hussey, P. Rlabkey: Data Exchange Between R and ‘LabKey’ Server, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Rlabkey (2023).

Ewing, M. mgsub: Safe, Multiple, Simultaneous String Substitution, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mgsub (2021).

Chang, W. et al. shiny: Web Application Framework for R. , https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=shiny (2023).

Burger, G. shinyTime: A Time Input Widget for Shiny, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=shinyTime (2022).

Atkins, A., Wickham, H., McPherson, J., Allaire, J. rsconnect: Deploy Docs, Apps, and APIs to ‘Posit Connect’, 'shinyapps.io’, and ‘RPubs’, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rsconnect (2023).

Fairchild, K. D. et al. Septicemia mortality reduction in neonates in a heart rate characteristics monitoring trial. Pediatr Res 74, 570–575. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2013.136 (2013).

Steffen Moritz, T.B.-B. imputeTS: Time Series Missing Value Imputation in R. R J. 9, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2017-009 (2017).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2009).

Quintana, D. S. Statistical considerations for reporting and planning heart rate variability case-control studies. Psychophysiology 54, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12798 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms. Thilagavathy Jagan for her help during the implementation of the data acquisition and storage as well as with the coding of some of the computational procedures. We would also like to thank the study nurse Isabel Gonzalez for data acquisition. Thank you to Elisabeth Büchler and Mareike Hug for their assistance in recruitment of study participants.

Funding

This study was supported by a project grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (no 179374).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. L.R.W. and S.K. analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the first and final version of the manuscript. L.R.W. made the tables and graphs embedded in the manuscript. E.D.E. conceived and implemented the data acquisition, and the data storage and management procedures. E.D.E. conceived and implemented the computational and data analysis approach, including data quality management. E.D.E. and C.S. designed and implemented the graphical user interface. S.M.S. was the principal investigator obtaining study funding, leading the study design, verifying all statistical calculations, and contributing to data interpretation. B.S. analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the first and final version of the manuscript. Also, all authors helped in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramin-Wright, L., Kaempfen, S., Delgado-Eckert, E. et al. Sample entropy of oxygen saturation in preterm infants. Sci Rep 15, 6104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89174-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89174-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predicting the treatment-requiring retinopathy of prematurity using birth weight, laboratory data and continuous peripheral capillary oxygen saturation monitoring

Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology (2025)