Abstract

To explore whether collegiate recreational runners of different genders exhibit different lower extremity kinematics following a 5 km running time trial. Thirty collegiate recreational runners (15 males, 15 females) participated. The participants performed kinematic tests using IMUs before and after the 5 km running time trial. Spatiotemporal parameters were recorded via the Garmin HRM-RUN during the 5 km running time trial. The peak hip, knee and ankle joint angles and angular velocity were compared within and between groups using two-way analysis of variance. Spatiotemporal parameters were compared between groups using independent t tests. In terms of kinematic parameters, gender and time have a significant interaction effect on the peak knee internal rotation angle (P = 0.036) after 5 km running time trial. The peak ankle eversion angular velocity after running was significantly greater than that before running in male runners (P = 0.015). In terms of spatiotemporal parameters, the average cadence of females was significantly greater than that of males during running (P = 0.003). The Collegiate recreational runners presented gender-specific lower extremity kinematic characteristics following a 5 km running time trial. The peak knee internal rotation angle significantly increased after the 5 km running time trial in female runners. It should be paid more attention to the association between gender-specific lower extremity kinematic characteristics and running-related injuries in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Running is easy and practical, with millions of people around the world participating in running to improve their body composition, musculoskeletal health, cardiovascular health and psychological health1. However, although running can have many positive effects, its high risk of musculoskeletal injuries is of concern. Epidemiological surveys have shown that the injury rate of running ranges from 19 to 79%2,3, with sustained injuries being the most common reason for people to stop running4.

Most running-related injuries (RRIs) are overuse injuries located in the lower extremities, such as medial tibial stress syndrome, patellofemoral pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, stress fractures of the tibia and plantar fasciitis5. A recent umbrella review revealed that biomechanical characteristics exhibited large effect sizes in increasing the risk for RRIs6. Meanwhile, the incidence of RRIs is related to sex, with female runners having a significantly greater incidence of injury than male runners do7. A number of studies have shown that gender differences in the incidence of RRIs are related to running kinematics between males and females8,9,10,11. Some studies have suggested that differences in the peak hip adduction angle, peak internal rotation angle and peak knee abduction angle between the frontal and transverse planes lead to a greater incidence of RRIs among female runners9,10. Sinclair12 compared the differences in running kinematics between males and females and reported that the peak hip flexion angle of females differed from that of males in the sagittal plane. This13 reported that females exhibit significantly greater peak external knee valgus and hip internal rotation than males do during running. In addition, a previous study compared the effects of 5 km treadmill running on the difference in lower extremity kinematics in female amateur runners between the initial and terminal phases and reported that peak ankle eversion, peak knee abduction, peak ankle dorsiflexion velocity and peak hip internal rotation significantly increased in the terminal phase compared with the initial phase14. With prolonged running, the kinematics of the lower extremities undergo significant changes, which may increase the risk of RRIs.

If running kinematics following prolonged running can be clarified, more targeted injury prevention strategies can be established based on the different kinematic characteristics between genders. However, although numerous studies have explored the running kinematics of males or females, there is a gap in understanding concerning the comparison of changes in running kinematics following a 5 km running time trial that may cause fatigue, especially between genders. In addition, there are also limited gender-specific training exercises for injury prevention. Therefore, further research is needed to elucidate gender-specific changes in running kinematics following prolonged running.

Therefore, this study collected and compared lower extremity kinematics from collegiate recreational runners of different genders before and after a 5 km running trial. The aim of this study was to deepen the understanding of gender-specific kinematics models and provide a theoretical basis for the prevention and treatment of RRIs. It was hypothesized that the kinematics of recreational runners are gender-specific: peak angles and velocities of the hip and knee joints in the sagittal and transverse planes might significantly increase following a 5 km running time trial in both males and females, with females being greater than males.

Materials and methods

Participants

An a priori power analysis (β = 0.2; P = 0.05) was conducted on the basis of a previous study8 with G*POWER 3.1 (Universität Kiel, Germany) to determine the sample size needed for the present study, and the minimum sample size required was 24. To maximize the statistical power and detect potential gender differences, we recruited 30 participants: 15 males (mean ± SD age: 20.33 ± 1.84 years; height: 174.67 ± 6.54 cm; mass: 64.23 ± 3.85 kg) and 15 females (mean ± SD age: 20.73 ± 1.67 years; height: 161.93 ± 2.71 cm; mass: 53.42 ± 3.47 kg). All of the participants were rearfoot strikers, were free from any injuries within 3 months prior to testing, and were running a minimum of 20 km/week. The demographic characteristics of the participants are provided in Table 1. Before participation, all participants were required to complete a written informed consent form and a health history screening. All protocols and procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Physical Education and Sports, Beijing Normal University (IRB approval number: TY2023101002).

Experimental protocol

Instrumentation

The kinematics of the lower extremities were measured via an inertial measurement unit (IMU) system. IMUs are tools for measuring motion capture and are gaining popularity in the field of human motion capture15. The IMU system (STT system, Basque Country, Spain) used in this study contains seven IMUs for tracking three-dimensional motion.

Spatiotemporal parameters, including cadence, stride length, vertical oscillation, the vertical ratio and contact time, are important indicators of gait during walking or running16. Monitoring spatiotemporal parameters of gait is important for assessing performance and predicting overuse injuries17. Garmin HRM-RUN is a heart rate monitor produced by Garmin. The participants wore it on their chest to monitor their heart rate and collect spatiotemporal parameters during running. The reliability of the Garmin HRM-RUN has been proven in previous studies18,19.

Procedures

Data were collected at the Sports Science Research Laboratory at Beijing Normal University. Before data collection, participants were informed of the objectives, procedures, and potential risks of participation in the study. This study recruited a total of 46 participants and conducted health history screenings and cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPET). Health screening mainly included investigations of the medical history. The cardiopulmonary exercise test was conducted using Cosmed K5 (Cosmed, Italy), where participants engaged in a progressive load test on a treadmill (Rodby RL-2000E, Sweden) until they were completely exhausted. The test was terminated when the following two or more criteria are met: (1) the oxygen uptake curve plateaus or decreases; (2) the respiratory quotient (RQ) is ≥ 1.10; and (3) it is difficult for athletes to continue exercising20. Based on the performance of the CPET, 30 recreational runners (male = 15; female = 15) with similar peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) values (male: 45.67 ± 2.90; female: 45.58 ± 3.53) were selected for this study.

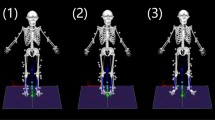

Before lower extremity kinematics were collected, seven IMUs were placed with adhesive nylon straps on both sides of the sacrum, thigh, shank and foot (Fig. 1). Each IMUs incorporates three triaxial sensors (a magnetometer, an accelerometer and a gyroscope) that measure the corresponding magnitudes in the three axes of space (X, Y, Z). The information from each of these three sensors is combined by means of a fusion algorithm, which allows the calculation of the spatial orientation (three angles) of the sensor with respect to an absolute reference or with respect to the initial position of the sensor, and converts the variables were obtained in the form of quaternions into angles by the ISen software21. The hip joint angle was defined as the rotation of the femur coordinate system relative to the pelvic coordinate system; the knee joint angle was defined as the rotation of the calf coordinate system relative to the femur coordinate system; and the ankle joint angle was defined as the rotation of the foot coordinate system relative to the calf coordinate system22. The joints rotate around the x, y, and z axes in sequence to obtain the angles of the joints in the sagittal plane (flexion), frontal plane (eversion) and transverse plane (internal rotation)22. A standing calibration trial was obtained to define the segmental coordinate systems and joint axes. After the calibration trial, the participants ran along a 30 m runway at a speed of 4 ± 0.3 m/s. The running speed was monitored using photoelectric cells placed 1.92 m apart along the runway. A successful trial was defined when the running speed was within ± 5% of the target speed. A total of three successful trials were collected from each participant.

After completing the first test of running kinematics, the seven IMUs were removed. The participants were asked to complete a 5 km running time trial on the 400 m track near the laboratory. We encouraged participants to run with near-maximum effort. During the process of running, participants wore the Garmin HRM-RUN to collect heart rate and spatiotemporal parameters. After completing the 5 km running time trial, the participants returned to the laboratory as soon as possible for the second test of running kinematics. The testing process was the same as that of the first test.

Data analysis

Real-time kinematic data collected by the sensor signals of the IMU system can be transmitted wirelessly to the software iSen 3.06. In the spatial three-dimensional coordinate system of the iSen inertial motion capture system, the global X-axis was defined as the vertical axis, the global Y-axis was defined as the anteroposterior axis, and the global Z-axis was defined as the lateral axis. The kinematic data were exported to a CSV-formatted file in iSen 3.06 software, and 10 consecutive gait cycles were analysed. Data were obtained from each participant’s dominant leg, which was defined as the leg they preferred to use when kicking a ball23. The spatiotemporal parameters collected by Garmin HRM-RUN can be directly transmitted to Garmin Connect software.

Statistical analysis

The following variables were extracted from the time series data: peak angle and peak velocity of the lower extremity joints (hip, knee, and ankle) in three planes (sagittal, frontal and transverse). The Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test and Levene test were used to test the normality and homogeneity of variance of the continuous data, respectively. The data that did not conform to a normal distribution (peak hip internal rotation angle, peak knee abduction angle, peak ankle dorsiflexion angle, peak ankle internal rotation angle, and peak hip internal rotation velocity) were converted using JMP 17.0. Descriptive data are presented as the means and standard deviations. Statistical analyses of kinematic characteristics were performed using two-way analysis of variance, and spatiotemporal parameters were analysed via independent t tests. For all analyses, the significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Participant characteristics

The participant characteristics are reported in Table 2. There was no difference in age (P = 0.536), BMI (P = 0.252) or VO2peak (P = 0.938). However, males were taller (P = 0.000) and weighed more (P = 0.000). The participants completed a 5 km running time trial on a standard 400 m track field. The time required to run 5 km for males and females was 1437.4 ± 84 s and 1441.7 ± 86 s, respectively (P = 0.892). The average heart rate during running was 167.93 ± 14.74 in males and 166.07 ± 10.19 in females (P = 0.252).

Spatiotemporal parameters

Independent sample t tests were used to analyse the spatiotemporal parameters between the groups, and the results are shown in Table 2. The average cadence of female runners was significantly greater than that of male runners (P = 0.003), whereas there was no statistically significant difference in stride length (P = 0.19), vertical oscillation (P = 0.057), the vertical ratio (P = 0.07) or contact time (P = 0.55).

Kinematic characteristics

Two-way analysis of variance was used to analyse the running kinematics, and the results are shown in Table 3. The results indicated that sex and time have a significant interaction effect on the peak knee internal rotation angle (P = 0.036). In addition, the peak ankle eversion velocity after running was significantly greater than that before running in males (P = 0.015).

Compared with the male group, the female group presented significant increases in the peak knee flexion angle (P = 0.007), peak hip flexion velocity (P = 0.000), peak knee flexion velocity (P = 0.000), peak hip abduction velocity (P = 0.000), and peak knee internal rotation velocity (P = 0.027) and a significant decrease in the peak ankle dorsiflexion angle (P = 0.035) before running. Compared with the male group, the female group presented significant increases in the peak knee flexion angle (P = 0.002), peak knee internal rotation angle (P = 0.01), peak hip flexion velocity (P = 0.000), peak knee flexion velocity (P = 0.000), peak hip abduction velocity (P = 0.004), peak knee internal rotation velocity (P = 0.009) and peak ankle eversion angle (P = 0.026) after running.

Discussion and implications

The current study evaluated gender differences in lower extremity kinematics following a 5 km running time trial in colligate recreational runners. The results of this study partially support our hypothesis that the peak angle of the knee joints in the transverse plane significantly increased after the 5 km running time trial in female runners. This result indicates that prolonged running has a gender-specific effect on the lower extremity kinematics of recreational runners.

In this study, thirty recreational runners with similar running performance were encouraged to complete a 5 km running time trial with near-maximum effort. The two groups of runners completed the running trial in similar times (male: 1437.4 ± 84 s; female: 1441.7 ± 86 s; P = 0.892). Previous studies stated that the participants ran until they reached a state of exertion as determined by one of two events: (1) reaching 85% of the participant’s estimated heart rate maximum (208-(0.7 × age))24 or (2) a score of 17 on the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale25. Although this study did not record the RPE of the participants, some fatigue can be observed from the average HR (male: 167.93 ± 14.74 bpm/min; female: 166.07 ± 10.19 bpm/min; P = 0.252). A previous study revealed that as running time increases, fatigue gradually increases, and the human body spontaneously adjusts and changes its running movement patterns26. Therefore, fatigue is believed to alter running kinematics27. The results revealed that the peak knee internal rotation angle of females significantly increased after the 5 km running trial, which was similar to the findings of previous studies28,29. Dierks28 investigated the effects of running in an exerted state on lower extremity kinematics in recreational runners and reported that the peak knee internal rotation angle significantly increased from the beginning of the run to the end of the run. However, the above studies did not mention the sex of the participants and cannot reveal the gender differences in kinematics before and after running fatigue; our research filled this gap. Harrison29 compared the difference in kinematics during treadmill running (2.68 m/s) between novice and experienced female runners and reported that novice runners displayed greater peak knee internal rotation angles than experienced runners did, which revealed that the peak knee internal rotation angle displayed by novice runners may help explain their greater risk for overuse injury. Radzak30 reported that increased peak knee internal rotation angle during fatigue running was associated with decreased isometric hip-abductor torque and that isometric hip-abductor torque and eccentric control should be strengthened to prevent or rehabilitate injuries. In our study, there was no difference in peak knee internal rotation angle before running between the two groups (males: 13.48 ± 9.12; females: 13.52 ± 8.42; P = 0.984), whereas it significantly increased in the female group after running (males: 13.39 ± 9.81; females: 25.14 ± 13.94; P = 0.000). Previous studies have suggested that runners who are at high risk of iliotibial band syndrome exhibit greater peak knee internal rotation than do those who remain uninjured31,32,33,34. There was no significant difference in peak ankle internal rotation velocity between the two groups (males: 175.64 ± 26.81 vs. 162.52 ± 44.09, P = 0.178; females: 185.70 ± 50.42 vs. 197.56 ± 50.22, P = 0.071), but an analysis of the data of the two groups revealed that male runners presented a significant downwards trend, whereas female runners presented a significant upwards trend. The results may not be robust enough due to the sample size, but they are still highly important for understanding gender-specific kinematic differences. In addition, this study also revealed gender differences in the peak knee flexion angle, peak ankle dorsiflexion angle, peak hip flexion velocity, peak knee flexion velocity, peak hip abduction velocity, peak knee internal rotation velocity and peak ankle eversion velocity, no significant interaction effect was found between the two groups. Future research should continue to focus on a series of relevant indicators to deepen the understanding of gender-specific kinematics models.

The spatiotemporal parameters revealed that the average cadence during 5 km running was significantly greater in females than in males (males: 169.73 ± 8.11, females: 182.27 ± 12.33; P = 0.003). In our study, although male and female runners have similar HRs during 5 km running, differences in anatomical structure and morphology generally lead to lower muscle strength in females than in males, so greater muscle fatigue might occur in female runners. An increase in cadence results in a decrease in step length and, in turn, requires less force to propel forwards35. This could be an adaptation to reduce loading at the hip and knee joints during running, which might be an adaptive mechanism to optimize energy expenditure and prevent RRIs for female runners19. Owing to the limited research on the gender specificity of spatiotemporal parameters, further studies are needed in the future.

Some limitations in this study should be taken into consideration. First, only collegiate recreational runners were included; as a result, the findings should only be applied to collegiate recreational runners. Second, although this study assessed the participants’ VO2peak to ensure that there was no significant difference in sport performance between the two groups, it did not collect data on the lower extremity muscle strength of the participants to establish a closer relationship between fatigue and kinematics. Further research will be conducted in the future. Third, only peak values of lower extremity kinematics were assessed. Further investigations should focus on all continuous values during the stance phase or gait.

Conclusion

The collegiate recreational runners presented gender-specific lower extremity kinematic characteristics following the 5 km running time trial. The peak knee internal rotation angle significantly increased after the 5 km running time trial in female runners. It should be paid more attention to the association between gender-specific lower extremity kinematic characteristics and running-related injuries in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Please contact: lidaxin@mail.bnu.edu.cn.

References

Burke, A., Dillon, S. & O’Connor, S., et al. Aetiological factors of running-related injuries: A 12 month prospective “running injury surveillance centre” (RISC) study. Sports Med-Open. 46(9) (2023).

Hollander, K. et al. Prospective monitoring of health problems among recreational runners preparing for a half marathon. BMJ Open Sports Exerc. Med. 4(1), e000308 (2018).

Van Middelkoop, M. et al. Prevalence and incidence of lower extremity injuries in male marathon runners. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 18(2), 140–144 (2008).

Fokkema, T. et al. Reasons and predictors of discontinuation of running after a running program for novice runners. J. Sci. Med. Sports 22(1), 106–111 (2019).

Bredeweg, S. W. et al. Differences in kinetic variables between injured and noninjured novice runners: A prospective cohort study. J. Sci. Med. Sports 16(3), 205–210 (2013).

Correia, C. K. et al. Risk factors for running-related injuries: An umbrella systematic review. J. Sports Health Sci. 13(6), 793–804 (2024).

Taunton, J. E. et al. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 36, 95–101 (2002).

Ferber, R., Davis, I. M. & Williams, D. S. III. Gender differences in lower extremity mechanics during running. Clin. Biomech. 18, 350–357 (2003).

Malinzak, R. A. et al. A comparison of knee joint motion patterns between men and women in selected athletic tasks. Clin. Biomech. 16, 438–445 (2001).

Almonroeder, T. G. & Benson, L. C. Sex differences in lower extremity kinematics and patellofemoral kinetics during running. J. Sports Sci. 35(16), 1575–1581 (2017).

Chumanov, E. S., Wall-Scheffler, C. & Heiderscheit, B. C. Gender differences in walking and running on level and inclined surfaces. Clin. Biomech. 23, 1260–1268 (2008).

Sinclair, J. et al. Gender differences in the kinetics and kinematics of distance running: Implications for footwear design. Int. J. Sports Sci. Eng. 6(2), 118–128 (2012).

Thijs, Y. et al. Is hip muscle weakness a predisposing factor for patellofemoral pain in female novice runners? A prospective study. Am. J. Sports Med. 39(9), 1877–1882 (2011).

Quan, W. et al. comparative analysis of lower limb kinematics between the initial and terminal phase of 5km treadmill running. J. Vis. Exp. 161, e61192 (2020).

Stołowski, Ł et al. Validity and reliability of inertial measurement units in active range of motion assessment in the hip joint. Sensors (Basel). 23(21), 8782 (2023).

Lohman, E. B., Balan Sackiriyas, K. S. & Swen, R. W. A comparison of the spatiotemporal parameters, kinematics, and biomechanics between shod, unshod, and minimally supported running as compared to walking. Phys. Ther. Sports 12, 151–163 (2011).

Scataglini, S. et al. Measuring spatiotemporal parameters on treadmill walking using wearable inertial system. Sensors (Basel). 21(13), 4441 (2021).

Paolo, T., Nicola, G. & Enrico, S, et al. Running power: Lab based versus portable devices measurements and its relationship with aerobic power. Eur. J. Sports Sci. 22, 1555–1568 (2022).

Gómez, M. J. et al. Differences in spatiotemporal parameters between trained runners and untrained participants. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31, 2169–2175 (2017).

Millet, G. P. & Bentley, D. J. Physiological differences between cycling and running: Lessons from triathletes. Sports Med. 39(3), 179–206 (2009).

Sánchez-Rodríguez, A. et al. Sensor-based gait analysis in the premotor stage of LRRK2 G2019S-associated Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 98, 21–26 (2022).

Hao, L. T. et al. Effects of different trunk-restraint squatting postures on human lower limb kinematics and dynamics. J. Med. Biomech. 39(1), 118–124 (2024).

Ruas, C. V. et al. Lower-extremity strength ratios of professional soccer players according to field position. J. Strength Cond. Res. 29(5), 1220–1226 (2015).

American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (2000).

Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (1998).

Kim, H. K., Mirjalili, S. A. & Fernandez, J. Gait kinetics, kinematics, spatiotemporal and foot plantar pressure alteration in response to long-distance running: Systematic review. Hum. Mov. Sci. 57, 342–356 (2018).

Derrick, T. R., Dereu, D. & McLean, S. P. Impacts and kinematic adjustments during an exhaustive run. Med. Sci. Sports Exer. 34(6), 998–1002 (2002).

Dierks, T. A., Davis, I. S. & Hamill, J. The effects of running in an exerted state on lower extremity kinematics and joint timing. J. Biomech. 43(15), 2993–2998 (2010).

Harrison, K. et al. Comparison of frontal and transverse plane kinematics related to knee injury in novice versus experienced female runners. J. Appl. Biomech. 37(3), 254–262 (2021).

Radzak, K. N. & Stickley, C. D. Fatigue-induced hip-abductor weakness and changes in biomechanical risk factors for running-related injuries. J. Athl. Train 55(12), 1270–1276 (2020).

Miller, R. H. et al. Lower extremity mechanics of iliotibial band syndrome during an exhaustive run. Gait Posture 26, 407–413 (2007).

Noehren, B., Davis, I. & Hamill, J. ASB clinical biomechanics award winner 2006 prospective study of the biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 22, 951–956 (2007).

Friede, M. C., Innerhofer, G., Fink, C., Alegre, L. M. & Csapo, R. Conservative treatment of iliotibial band syndrome in runners: Are we targeting the right goals?. Phys. Ther. Sports 54, 44–52 (2022).

Day, E. M. & Gillette, J. C. Acute effects of wedge orthoses and sex on iliotibial band strain during overground running in nonfatiguing conditions. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 49(10), 743–750 (2019).

Jaén-Carrillo, D. et al. Influence of footwear, footstrike pattern and step frequency on spatiotemporal parameters and lower-body stiffness in running. J. Sports Sci. 40(3), 299–309 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the runners who participated in this study for their collaboration. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D.X, L.Y.L, P.C and F.Y.Y collected the data of test. L.D.X wrote the first draft of the manuscript. L.D.X, L.Y.L, P.C, F.Y.Y and T.D.H read and revised multiple drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received Institutional Ethics Approval from the College of P.E and Sport, Beijing Normal University, China (IRB approval number: TY2023101002) . Participants gave written informed consent before taking part. The study was performed in accordance with the standards of ethics outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Liu, Y., Feng, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of the effects of gender on lower extremity kinematics following a 5 km running time trial in collegiate recreational runners. Sci Rep 15, 5166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89188-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89188-6