Abstract

3D actual frequencies in the machined Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4, KDP) crystal surfaces are extracted and reconstructed through continuous wavelet transform (CWT) and power spectral density (PSD) methods. The temperatures of machined KDP crystals, which are exposed to laser irradiation with a wavelength of 1.064 μm and power of 200 MW/μm2 in 1 ns, are analyzed with wave optics. The ideal surfaces have been selected to analyze the impact of wavelength and amplitude on the internal temperature field of KDP crystals. Along the orthogonal direction of cutting, the closer the dominant 3D wavelength of the surface is to the laser’s incident wavelength, the greater the temperature increase. The maximum temperature decreases with the further increase of the wavelength (1.064–20 μm). The effect of the frequency feature on temperature in the cutting direction is similar to that in the orthogonal direction, but with a lesser impact on temperature variation. The temperatures of 3D surfaces and sub-surfaces above 10 μm depth are calculated using the wave optics theory. The maximum temperature field throughout the crystal is in the subsurface layer. With the increase of wavelength, the positions of the maximum temperature extend to the interior of the KDP crystal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As nonlinear optical crystals with superior performance, KDP crystals are widely used in high-power laser systems and inertial confinement fusion (ICF) facilities1,2,3,4,5,6. In these fields, laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) is an important parameter to evaluate the performance of machined KDP components, and it severely limits the development of ICF. The laser-induced damage of KDP crystals comprises ablation, melting, brittle fractures, and cracks, and most of these failures occur in the machined surfaces7,8,9. All factors influencing laser-induced damage are related to the temperature caused by laser irradiation. The temperature of KDP crystals is affected by the internal material structure and composition, such as point defects, dislocations, impurities (e.g., metal ions and organic matter), crystal growth environment, and seed crystals10,11,12,13,14,15. In addition, surface topographic features, that is, surface roughness and micro-scale waveness, affect the thermal and optical performance of KDP crystal components16,17,18,19.

Accurate extraction of the topography in the machined surfaces is beneficial for further analysis of their effects on the optical performance of KDP components. Various methods such as PSD, fractal method, and wavelet transform are widely used for surface topography evaluation20,21,22. In particular, the machined surfaces of KDP crystals were characterized by using wavelet, fractal, and PSD methods to study the relationship between the surface roughness and the fractal dimension during ultra-precision fly cutting23,24. In predicting surface roughness and optimizing the machining parameters of milling, the surface of milling parts is frequently analyzed by using fast Fourier transform and discrete wavelet transform (DWT)25,26. Moreover, PSD is often used to elucidate the effect of processing parameters on the roughness of the surface exposed to abrasive air jet micromachining27. The textural features from the surface image of the workpiece can be decomposed by undecimated wavelet transform to assess the wear of the tool caused by the turning process28. Wavelet transform such as DWT is a common method to decompose frequency features, except for arbitrary frequencies, from machined surfaces.

The influence of surface topography on the light and electric fields of machined KDP crystals was investigated using the calculation models based on finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) approach and Fourier modal method (FMM)29,30,31. The effect of different shapes of scratches on the laser damage threshold of the KDP crystal surface machined by single point diamond fly cutting was studied by FDTD method, which entailed an increase of the maximum LIDT value with increasing diameter of the circular scratch32. There was a medium-frequency waviness error along the cutting direction on the surface of the KDP crystal machined by an ultra-precision single-point diamond flying knife, which led to a decrease in the optical performance of the crystal and limited the ability of the latter in inertial confinement fusion33. The exploration of the impact of scratch characteristics on the surface and damage threshold of the high-quality KDP crystal using the FMM revealed a decrease in the threshold strength from 132 to 102TW/cm2 in the presence of surface scratches with a width of 2.5 μm and a depth of 0.1 μm34. The influence of surface scallop tool marks produced during the micro-milling repair process of the KDP crystal on its optical performance was studied and found the dependence of the light intensity on the tool marking period and scallop height35. Laser damage tests were conducted to observe the laser damage morphology of the KDP crystal surface, enabling one to establish that transverse cracks on the surface were conducive to the laser damage of the KDP crystal36,37.

In all these researches, ideal frequency features were used in the form of trigonometric functions to build the models for simulating and analyzing the influence of surface topography on the laser damage and LIDT. However, ideal frequency features have no apparent correlation with actual frequency features that might exist in the machined surface. This limitation would produce errors in the analysis results. In this paper, CWT and PSD are used to extract and reconstruct actual frequency features in the actually machined surface. In particular, the wave optics theory is applied to describe the effects of surface frequency features on the temperature of the KDP crystal. Special attention is paid to the roles of wavelengths and amplitudes in the temperature of the KDP crystal. The effect results of actual frequency features on the temperature of the KDP crystal can effectively optimize the practical machining parameters and achieve better surface topography of the KDP crystal to improve the LIDT performance of the KDP components.

Methods and experiments

Cutting experiment

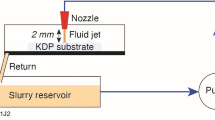

Machined KDP crystal surfaces were obtained by single-point diamond turning (SPDT) as shown in Fig. 1. The cutting and tool parameters are listed in Table 1.

The morphology of a typical SPDT machined KDP crystal was measured using white light interferometer (Fig. 2). Figure 3 depict the surface topography results, including the 3D surface morphology and the 2D profile obtained from the sampling points at the middle position of the 3D pattern perpendicular to the machined direction. The sampling area is as large as 360 μm × 360 μm; the number of sampling points is 256 × 256, and the sampling period is 1.412 μm/pixel. The 3D topography exhibits the anisotropically distributed surface frequency features that can be thoroughly analyzed from the 2D surface profile (Fig. 3). The extracted 2D profile evidences plenty of frequecy features that can disturb the laser transmission and have a significant effect on the temperature of the KDP crystal.

Extraction and reconstruction methods

The PSD method used in this study to quantitatively describe the surface micro-topography of the KDP crystal can be described by the formula below:

where f is the spatial frequency; L is the sampling length; z(f, L) is the Fourier transform of 2D surface profile.

Frequency features existing in the machined KDP surface are analyzed based on the PSD results. The frequency features are reconstructed by CWT method defined as:

where W is the continuous wavelet coefficient that is determined by (x) which is the Mexh wavelet basis in this paper; f(x) is the original signal; a is the scale factor; b is the position factor (where b is 0 in the paper).

The scale factor a of CWT could be expressed as the relationship between the wavelet base and the specific frequency as follows:

where fc is the wavelet base center frequency of the Mexh (fc = 0.25); Δ is the sampling period of the measuring instrument; fs is the center frequency of the actual frequency defined as:

where f is the actual frequency of the machined surface; L is the length of sampling boundary; N is the number of sampling points within the length of the sampling boundary.

The wavelet coefficient is the result of CWT analysis, which is dimensionless. The 2D profile of the actual frequency features f(t) needs to be reconstructed using wavelet coefficients as follows:

where Cψ are the permissible conditions.

Simulation model

Based on the wave optics theory and the information about surface frequency features, the theoretical investigation of the effect of ideal and actual frequency features on the temperature field of the KDP crystal is performed by building the model as shown in Fig. 4. The frequency features used in this model are extracted and reconstructed from the original surface profile from Fig. 2.

The electric field in the KDP crystal is solved by wave equation of the laser beam propagating in the KDP crystal. And the wave equation can be expressed as:

where ▽ is the Hamiltonian; εr is relative dielectric constant (εr = 2.1); σ is the electrical conductivity; μr is the relative permeability (σ = μr = 1) indicating the complete energy loss; k0 is the wave number; E is the electric field.

When solving the problem of electromagnetic field, it is necessary to simulate a domain with an open boundary. Under this condition, the boundary of the computational domain can support the passage of electromagnetic waves in a non-reflective manner. Scattering boundary conditions and perfect matching layers are applied in our model. If the 2D model is considered only, the electromagnetic wave is meant to propagate in the X–Z plane and the electric field is polarized in the Y direction. It is assumed that the rest of the space, except for the model itself, is completely filled with vacuum (no energy flow density is absorbed), and the exterior is transparent to all radiation. In this respect, the scattering boundary conditions of the lower boundary can be written as:

where Ey is the y-axis component of the electric field.

The energy of electromagnetic losses determine the temperature of the KDP crystal. As a heat source in the anlysis of part of heat transfe, the energy of electromagnetic loss Pd can be determined as:

where n is the refractive index; J is the current density; E is the electric field intensity.

The heat conduction of the laser beam and the temperature distribution in the KDP crystal can be calculated as:

where T is the temperature; ρ is the density; c is the specific heat; t is the time; z is the direction along the coordinate axis (z-axis); k is the thermal conductivity.

The boundary conditions of the upper and lower profiles are defined as:

where h is the depth of the crystal in the Z direction of computation model. Since the boundaries on both sides are set to be in adiabatic state, the corresponding boundary conditions can be computed as:

The solution of thermal stress is based on the thermoelastic equation and the mechanical boundary condition. The thermal stress is defined as:

where Fth is the thermal stress; M is the Young’s modulus; α is the coefficient of thermal expansion; T is the current temperature of the KDP crystal; T0 is the initial temperature of the KDP crystal.

The incident direction of electromagnetic waves is the negative direction along the Z axis shown in Fig. 4. When the upper boundary is infinitely far away from the lower boundary, there is no electromagnetic wave reflection from the former through the interior of the crystal. This condition admits that the energy is completely absorbed. According to the 2D uniform absorbing state of the geometric model under the action of the electromagnetic field, the parameters and experimental conditions of the incident laser beam and the heat conduction are set as follows: the unit linear polarized laser is used for vertical incidence; the laser is parallel to the main axis of the crystal; the power density of the incident laser beam is 200 MW/μm2; the wavelength of the incident laser is 1.064 μm; the initial temperature T0 of the KDP crystal is 293.15 K; the laser pulse duration t is 1 ns. The calculated coefficient of thermal expansion is 13 × 10–6/K. The material parameters of the KDP crystal are listed in Table 2.

Results and discussion

Extraction of actual surface frequency features

Figure 5 displays the frequency features obtained on the machined surface by PSD method. The values of the most pronounced peaks are 0.0083, 0.0112, and 0.0277 μm−1, whereas the power densities of other frequency features tend to zero. This indicates that the micro-topography of the surface under consideration is mainly influenced by these three frequency features.

Figure 6 shows the PSD calculation results of KDP crystals with different surface frequency characteristics. The low-frequency spatial frequency eigenvalues fx affected by the actual frequency feature of wavelength 100 μm and 53 μm are all 0.0084 μm−1, The low-frequency spatial frequency eigenvalues fx affected by the actual frequency feature of wavelength 74 μm are 0.0112 μm−1, The power spectrum with the low-spatial frequency eigenvalue fx has the largest value. This indicates that the mid-frequency spatial real frequency eigenvalue is the main spatial real frequency characteristic on the machined surface of the crystal. As the surface frequency feature increases, the power spectral value of the actual frequency feature in low-frequency space increases, as does the power spectral value of the main spatial frequency feature. The 3D topography of the machined surface changes significantly when the surface frequency characteristic is a single variable, resulting in a reduction of the machined texture in the machined area.

Analysis of temperature

Figure 7 shows the 3D surface topography reconstructed from the spatial frequency features obtained by continuous wavelet transform at different actual surface frequency feature. The periodic changes can be seen more obviously. The number of cycles of the 3D shape reconstructed increases with the actual surface frequency feature. The mid-frequency information of the three-dimensional surface morphology reflects the primary spatial frequency characteristics of the machined crystal surface. In contrast, the high-frequency information of the three-dimensional surface morphology is characterized by short wavelengths and weaker periodic variation patterns, providing the least information about the spatial frequency distribution. This is related to the properties of the selected machine tool and the crystal.

CWT results of different spatial frequency feature: (a) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (b) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (c) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm. (d) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (e) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (f) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm. (g) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (h) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (i) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm.

To comprehensively analyze the impact of wavelength and amplitude on the internal temperature field of KDP crystals, ideal surface wavelengths ranging from 0 to 120 μm with amplitudes of 1–20 nm, as well as ranging from 0 to 10 μm with amplitudes of 1–4 nm, were selected for fx and fy, respectively. Figure 8 shows a summary of the effects of different amplitudes of fx and fy frequencies on the maximum temperature of KDP crystals. Under identical amplitude conditions, the maximum temperature depends on the difference between the surface frequency wavelength and the incident laser wavelength. As the surface frequency wavelength increases, the influence of frequency characteristics on the maximum temperature of KDP crystals initially shows a sharp increase and then stabilizes on a fluctuating platform. When the wavelengths of fx and fy reach 1.064 μm, the maximum temperature peaks. This phenomenon occurs because once the surface frequency wavelength approaches the incident light beam wavelength at 1.064 μm, diffraction energy reaches its maximum and becomes concentrated. For fx wavelengths ranging from 1.064 to 20 μm, the maximum temperature decreases sharply with the increase of wavelength. For fx wavelengths ranging from 20 to 60 μm, the maximum temperature gradually decreases with the increase of wavelength. Beyond 60 μm wavelengths, the maximum temperature remains unchanged despite variations in surface frequency characteristics. The effect of the frequency feature on temperature in the fy direction is similar to that in the fx direction, but with smaller wavelengths and amplitudes, resulting in a lesser effect on temperature variation. Under identical wavelength conditions, the maximum temperature on the surface of KDP crystals depends on the amplitude of surface frequency characteristics, which increases with its growth.

Figure 9 illustrates the temperature-field distribution on the processed surface of KDP crystals under the influence of different frequency features. Higher temperatures on the surface correspond to areas where the amplitude of the surface morphology is larger, namely, the peaks of the surface morphology. For the different frequency feature of the actual machined surface, the highest temperatures of low-frequency surfaces are 368 K, 358 K, and 370 K, respectively. The highest temperatures of mid-frequency surfaces are 378 K, 369 K, and 387 K, whereas the highest temperatures of high-frequency surfaces are 384 K, 373 K, and 392 K. Conversely, the low temperatures on the surface correspond to areas where the amplitude of the 3D surface morphology is smaller, that is, the valleys of the surface morphology. When the beam passes through a crystal surface with low-frequency spatial actual features, the propagation path undergoes certain changes, thereby causing varying degrees of optical distortion. The beam converges at areas with high amplitudes on the surface, thereby generating more energy and increasing the temperature. By contrast, at areas with low amplitudes, the beam does not converge, resulting in less energy and lower temperatures. Therefore, when the spatial actual frequency feature peaks on the three-dimensional surface morphology are larger, calcium fluoride crystals are more susceptible to damage because of excessively high temperature and thermal stress.

Temperature distribution of surface with different frequency features: (a) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (b) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (c) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm. (d) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (e) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (f) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm. (g) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (h) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (i) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm.

Figure 10 respectively show the temperature field distribution inside the different frequency feature surface. For the different frequency feature of the actual machined surface, the highest temperatures in the crystals of low-frequency feature are 368 K, 368 K, and 370 K, respectively. The highest temperatures in the crystals of mid-frequency feature are 378 K, 384 K, and 387 K; the highest temperatures in the crystals of high-frequency feature are 369 K, 373 K, and 392 K. The analysis results of the temperature field within the crystal’s internal cross-section are similar to the previous 2D ideal profile analysis results. As the surface wavelength decreases, the periodicity of temperature variation within the crystal increases. The peak temperature rises with decreasing wavelength and manifests in regions closer to the surface. The depth of the KDP crystal model is only set to 50 μm, which limits the ability to reflect further differences. The maximum values of temperature decline with increasing original contour frequency, consistent with the earlier analysis results.

The internal temperature distribution of surface with different frequency features: (a) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (b) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm, (c) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 100 μm. (d) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (e) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm, (f) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 74 μm. (g) Low- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (h) Mid- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm, (i) High- frequency surface with a wavelength of 53 μm.

Conclusions

Actual frequency features in machined surface of KDP crystals are extracted and reconstructed using PSD and CWT methods. The calculations with wave optics theory method are performed to theoretically investigate the effect of actual frequency features on the temperature of KDP crystals.

-

1.

The surface frequency features with a wavelength less than 5 μm might result in the severe optical distortion of KDP crystals when the incident laser beam wavelength is 1.064 μm. Optical distortion leads to localized temperature rises within the crystal, reducing the laser damage threshold. Thus, the surface frequency features with a wavelength less than 5 μm should be avoided in the practical machining of KDP crystals. Otherwise, the amplitude should be as small as possible to prevent the harmful effect of such features on the crystal surface. If the wavelength is more than 60 μm, then the requirements for the amplitudes of surface frequency features can be reduced. Therefore, this study can provide effective guidance for optimizing the actual machining parameters of KDP crystals to achieve the best machined surface topography and LIDT performance in high-power laser systems.

-

2.

The ideal surfaces ware constructed to analyze the effects of wavelength and amplitude in different machining directions on the surface temperature of the KDP crystal. The effect of the frequency feature on temperature in the fy direction is similar to that in the fx direction, but with smaller wavelengths and amplitudes, resulting in a lesser effect on temperature variation. The maximum temperature caused by the surface frequency features is dependent on the wavelengths and amplitudes. The most serious effect on both parameters is observed when the wavelength of the surface frequency features is close to the incident laser wavelength (1.064 μm). In the wavelength range of 1.064–60 μm, the maximum temperature decreases with the increase of the wavelength. At a wavelength above 60 μm, the maximum temperature remains stable with varying surface frequency features. At the same wavelength, the maximum temperature is proportional to the amplitudes of surface frequency features.

-

3.

Both ideal surfaces and real surfaces of KDP crystal were considered separately, and they showed a remarkable effect on the temperature of KDP crystals. At a wavelength range of 0–140 μm, the maximum temperature of KDP crystals affected by the actual frequency features is 4–12 K higher than that for the ideal frequency features. In addition, the surface frequency features with different wavelengths affect the positions of the maximum temperature in KDP crystals. In particular, the position of the maximum temperature extends to the interior of the KDP crystal at the same amplitude of surface frequency with the increase of wavelength.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, X., Gao, H. & Yuan, J. Experimental investigation and analytical modelling of the tool influence function of the ultra-precision numerical control polishing method based on the water dissolution principle for KDP crystals. Precis. Eng. 65, 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2020.04.014 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Optomechanical analysis and performance optimization of large-aperture KDP frequency converter. Opt. Laser Technol. 109, 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.08.053 (2019).

Zhao, L. et al. Research on precision automatic tool setting technology for KDP crystal surface damage mitigation based on machine vision. J. Manuf. Process. 64, 750–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.02.012 (2021).

Spaeth, M. L. et al. Description of the NIF laser. Fusion Sci. Technol 69(1), 25–145. https://doi.org/10.13182/fst14-861 (2016).

Pei, G., Ye, L., Du, W., Yan, H. & Xu, X. Optimization of second-harmonic generation in large-aperture KDP crystals using multipoint support mounting configurations. Opt. Eng. 59(1), 016104–016104. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.oe.59.1.016104 (2020).

Luo, Y. et al. Laser-induced bulk modification in KDP crystal analyzed by optical spectroscopy under high-power laser excitation. J. Lumin. 207, 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.10.118 (2019).

Yang, Z. S. et al. Laser-induced surface burn: A feasible approach for controlled production of thermal damage and its monitoring based on acoustic emission. Lasers Eng. 33(4–6), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102984 (2016).

Tan, C. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation of localized CO2 laser interaction with fused silica during the process of surface damage mitigation. Results Phys. 16, 102936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2020.102936 (2020).

Wu, C., Guo, W., Li, R., Zhao, Y. & Zhou, Q. Thermal effect on oxidation layer evolution and phase transformation in grinding of Fe-Ni super alloy. Mater. Lett. 275, 128072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2020.128072 (2020).

Yin, H. et al. Growth study and characterization of KDP crystals grown by 2D translation method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 215, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.05.027 (2018).

Raghorte, V. R., Wakde, G. C., Meshram, N. S. & Rewatkar, K. G. Harvesting amino acid doped KDP crystal by temperature and time control using AVR microcontroller. Results Chem. 2, 100074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2020.100074 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Study on optical performance and 532 nm laser damage of rapidly grown KDP crystals. Opt. Mater. 114, 110995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2021.110995 (2021).

Baig, M. I., Anis, M. & Muley, G. G. Comprehensive study on crystal growth, optical and dielectric properties of potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate crystal influenced by organic additive salicylic acid. Optik 131, 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2016.11.085 (2017).

Yin, Y., Zhang, Y., Dai, Y., Xiao, Q. & Tie, G. Novel magneto-rheological finishing process of KDP crystal by controlling fluid-crystal temperature difference to restrain deliquescence. CIRP Ann. 67(1), 587–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2018.04.058 (2018).

Kanimozhi, D., Nandhini, S. & Indirajith, R. Effects of dyes in the growth, optical, mechanical and dielectric properties of KDP crystals. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 30(11), 10244–10255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-01361-6 (2019).

Xiao, M. et al. Prediction of surface roughness and optimization of cutting parameters of stainless steel turning based on RSM. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018(1), 9051084. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9051084 (2018).

Adamczak, S. & Zmarzły, P. Influence of raceway waviness on the level of vibration in rolling-element bearings. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 65(4), 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1515/bpasts-2017-0059 (2017).

Munoa, J. et al. Chatter suppression techniques in metal cutting. CIRP Ann. 65(2), 785–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2016.06.004 (2016).

Chen, W. & Sun, Y. Influence of low-spatial frequency ripples in machined potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystal surfaces on wavefront errors based on the wavelet method. Opt. Eng. 54(2), 024101–024101. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.oe.54.2.024101 (2015).

Pahuja, R. & Ramulu, M. Study of surface topography in abrasive water Jet machining of carbon foam and morphological characterization using discrete wavelet transform. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 273, 116249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2019.05.030 (2019).

Ünlüsoy, D. & Süzen, M. L. A new method for automated estimation of joint roughness coefficient for 2D surface profiles using power spectral density. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 125, 104156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104156 (2020).

Xiao, M. et al. Research on fault feature extraction method of rolling bearing based on NMD and wavelet threshold denoising. Shock Vib. 2018(1), 9495265. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9495265 (2018).

Chen, D., Zhang, S., Liu, J., Zha, C. & Pan, R. Morphological analysis of KDP-crystal workpiece surfaces machined by ultra-precision fly cutting. Materials 13(2), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13020432 (2020).

Qi, X., Shang, Y., Ding, Z. & Wei, W. Particularities and research progress of the cutting machinability of wood-plastic composites. Mater. Today Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106924 (2023).

Prabhakar, D. V. N., Kumar, M. S. & Krishna, A. G. A novel hybrid transform approach with integration of fast Fourier, discrete wavelet and discrete shearlet transforms for prediction of surface roughness on machined surfaces. Measurement 164, 108011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108011 (2020).

Shang, Y., Shen, J., Wei, W. & Zheng, B. Optimization of ball mill cylinder structure based on response surface optimization module and multi-objective genetic algorithm. J. Mech. Sci. Technol.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-024-0636-5 (2024).

Li, Q., Deng, Y., Li, J. & Shi, W. Roughness characterization and formation mechanism of abrasive air jet micromachining surface studied by power spectral density. J. Manuf. Process. 57, 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.07.039 (2020).

Danesh, M. & Khalili, K. Determination of tool wear in turning process using undecimated wavelet transform and textural features. Procedia Technol. 19, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2015.02.015 (2015).

Ji, J., Yu, M. & Guo, R. Fast finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method of two dimensional target scattering calculation by two-level hierarchical approach. Optik 203, 163951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.163951 (2020).

Spaeth, M. L. et al. Optics recycle loop strategy for NIF operations above UV laser-induced damage threshold. Fusion Sci. Technol. 69(1), 265–294. https://doi.org/10.13182/fst15-119 (2016).

Tian, Y. et al. Characteristics of laser-induced surface damage on large-aperture KDP crystals at 351 nm. Chin. Phys. Lett. 32(2), 027801. https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307x/32/2/027801 (2015).

Liu, Q. et al. Incident laser modulation by tool marks on micro-milled KDP crystal surface: Numerical simulation and experimental verification. Opt. Laser Technol. 119, 105610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.105610 (2019).

Miao, J., Yu, D., An, C., Ye, F. & Yao, J. Investigation on the generation of the medium-frequency waviness error in flycutting based on 3D surface topography. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 90, 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9404-8 (2017).

Cheng, J. et al. Determination of ultra-short laser induced damage threshold of KH2PO4 crystal: Numerical calculation and experimental verification. AIP Adv. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4945415 (2016).

Cheng, J. et al. Effect of surface scallop tool marks generated in micro-milling repairing process on the optical performance of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystal. Mater. Des. 157, 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2018.07.057 (2018).

Yang, H. et al. Dynamic behavior modeling of laser-induced damage initiated by surface defects on KDP crystals under nanosecond laser irradiation. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57300-2 (2020).

Pang, Q., Kuang, L. & Xu, Y. The influence of cutting parameters on micro-topography of frequency features extracted from the machined KH2PO4 surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 234(14), 1762–1770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954405420927561 (2020).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qilong Pang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, resources, Writing—original draft. Zulong Yan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing—review and editing. Jianlong Xiong: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, Q., Yan, Z. & Xiong, J. Effect of 3D surface topographies on the temperature field of machined potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals. Sci Rep 15, 11118 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89228-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89228-1