Abstract

Concrete frameworks require strong structural integrity to ensure their durability and performance. However, they are disposed to develop cracks, which can compromise their overall quality. This research presents an innovative crack diagnosis algorithm for concrete structures that utilizes an optimized Deep Neural Network (DNN) called the Ridgelet Neural Network (RNN). The RNN model was then adjusted with a new advanced version of the Human Evolutionary Optimization (AHEO) algorithm that is introduced in this study. The AHEO as a new method combines human intelligence and evolutionary principles to optimize the RNN model. To train the model, an image dataset has been used, consisting of labeled images categorized as either “cracks” or “no-cracks”. The AHEO algorithm has been employed to refine the network’s weights, adjust the output layer for binary classification, and enhance the dataset through stochastic rotational augmentation. The effectiveness of the RNN/AHEO model was evaluated using various metrics and compared to existing methods. The model’s performance is evaluated by metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and is compared to existing methods including CNN, CrackUnet, R-CNN, DCNN, and U-Net, achieving an accuracy of 99.665% and an F1-score of 99.035%. The results demonstrated that the RNN/AHEO model outperformed other approaches in detecting concrete cracks. This innovative solution provides a robust method for maintaining the structural integrity of concrete frameworks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conception

Concrete structures and members often suffer from cracks, which are a prevalent type of defect. Cracking is an unavoidable issue in concrete, arising from a variety of factors such as shrinkage due to drying, improper implementation of concreting operations, unprincipled design, and environmental conditions1.

Crack detection in structures of concrete is vital for ensuring their durability and safety. Traditionally, this task has been carried out through manual visual inspections conducted by skilled professionals. However, this approach is not only time-consuming but also prone to human error, as it heavily relies on the expertise and experience of the inspector. Furthermore, manual inspections may not always detect cracks in their early stages, leading to significant structural damage if left unaddressed2.

Fortunately, technological advancements have introduced automated methods to enhance the accuracy and efficacy of crack diagnosis in concrete structures. These methods typically involve two key stages: classification and feature extraction. Feature extraction utilizes image processing approaches to extract related data from images of the concrete structure. This process enables the identification of characteristics that indicate the presence of cracks, such as changes in color, texture, or shape3.

Related works

The extracted features are then inputted into a classification algorithm, which analyzes them to determine whether cracks are present or not. Classification serves as an important step in the automated crack detection process. However, many papers did crack quantification too, and found the size, type, and propagation detection of cracks. For example, Park et al.4 proposed concrete crack detection and quantification based on using deep learning and structured light. Guo et al.5 proposed another method based on strain-hardening cementitious fusions based on generative computer vision. In another work, Bayar et al.6 estimated concrete crack propagation based on machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning algorithms are commonly used for this purpose. These algorithms are trained on a vast dataset of labeled images, enabling them to learn patterns and relationships between the extracted features and the presence of cracks7.

Several works in the field of artificial intelligence were proposed for concrete crack detection. For example, Zhang et al.8 introduced a deep-learning approach, called CrackUnet, for automatic pixel-level crack identification in concrete structures. The study involved the development of a dataset comprising 1200 images with manual annotations. An enhanced Unet architecture was utilized along with a unique loss function, generalized dice loss, to enhance crack detection precision. The model’s efficacy was assessed on two datasets, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing techniques in terms of accuracy, training efficiency, and resilience. Potential limitations of the study included the relatively small dataset size, potential biases in manual labeling, and the necessity for additional real-world data testing to ensure applicability.

Hacıefendioğlu et al.9 designed a deep learning-based approach to identify cracks in concrete roads across various weather, illumination, and shooting conditions. The authors employed a pre-trained Faster R-CNN to diagnose cracks in 323 images of a concrete road surface, with a resolution of 4128 × 2322 pixels, and achieve promising outcomes. They conducted a parametric analysis to examine the influence of shooting distance and height, weather conditions, and illumination levels on crack detection. The analysis revealed that the number of detected cracks remains consistent in different weathers. The study’s limitations may encompass the restricted size of the dataset, the utilization of only one type of deep learning model, and the absence of consideration for other factors that could impact crack detection, such as road surface roughness or vegetation cover. Furthermore, the study solely concentrates on crack detection and does not address other forms of damage that may arise in concrete roads.

Iraniparast et al.10 indicated an approach for automatically diagnosing and segmenting cracks in structures of concrete using transfer learning (TL) and deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN) techniques. The proposed method consisted of two stages: crack detection and segmentation. The authors employed DCNN classifier models for crack detection, which exhibit outstanding efficiency with F1-scores ranging from 99.6 to 94.5%. In the crack segmentation stage, a multiresolution analysis of the image based on the wavelet transform is utilized, achieving an F1-score of 95.25% and demonstrating satisfactory and consistent performance across various segmentation metrics. The authors asserted that their approach holds the potential to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of concrete crack diagnosis and segmentation, thereby improving the overall Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) of concrete structures. Nevertheless, the study has certain limitations, including a limited dataset size, data selection bias, model complexity, transfer learning limitations, segmentation limitations, and absence of field testing.

Laxman et al.11 presented a method using deep learning to automatically detect cracks and estimate their depth in concrete structures. This method involves a binary-class convolutional neural network (CNN) for crack detection and a combination of regression models and convolutional feature extraction layers for depth estimation. The effectiveness of this framework was demonstrated through testing on a reinforced concrete slab, yielding promising results that highlight its potential for automating the inspection and evaluation of concrete structure conditions. However, it was essential to note several constraints of the research, such as its narrow concentration on a specific type of concrete structure, a relatively small dataset, and the acknowledged impact of image quality on the accuracy of depth estimation. Furthermore, the study does not address other potential factors that could affect crack detection and depth estimation, nor does it provide a comprehensive discussion of computational resources or a thorough comparison with existing approaches.

Nyathi et al.12 outlined a three-step strategy for detecting and measuring cracks in structures of concrete employing deep learning and image processing. The initial two steps focus on crack segmentation and classification through the use of custom CNN and U-Net models, while the final step involves assessing the width of a crack in millimeters employing a unique laser calibration technique. The method has shown high accuracy in both classification and segmentation, obtaining a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.16 mm in crack width measurement. This approach has various advantages over traditional image processing methods, such as the capability to assess cracks in millimeters, providing a more practical evaluation of structural harm for real-world applications. However, some drawbacks of this study include the need for a substantial amount of labeled data to train the deep learning models, sensitivity to changes in lighting conditions, and the potential requirement for alternative methods for different types of concrete structures. Further testing is recommended to confirm the method’s effectiveness across a broader range of concrete structures and to address assumptions regarding crack visibility and accessibility. Despite these limitations, the method proposed in the paper shows promise for crack detection and measurement in concrete structures.

There are also different surveys about using deep learning in concrete crack detection. For example, Kirthiga and Elavenil13 reviewed various image processing and machine-learning techniques for the detection of cracks on concrete surfaces. Overall, this study has demonstrated machine learning-based methods for automated crack inspection and has further developed such methods in the realm of civil engineering.

Amirkhani et al.14 reviewed the recent progress of vision-based classification and detection of concrete bridge defects. The review covered important components behind conventional frameworks, which are concrete defect taxonomy, public datasets, and evaluation metrics. The covered deep-learning-based classification and detection algorithms were also organized into layers of taxonomy with a thorough exposition of their benefits and shortcomings. We additionally provide both classification and detection baseline models for comparison on two widely used datasets. Notable challenges in concrete defect classification and detection and promising research directions were finally elaborated to not only build better models but also integrate them into real-world visual inspection systems, which deserve further research attention.

Zhang et al.15 summarized the application status of deep learning algorithms in identifying obvious defects in concrete from the three aspects of image classification, target detection, and semantic segmentation and pointed out the shortcomings of the current application. The paper explored the defect image acquisition method by analyzing both manual photography acquisition and UAV acquisition and described the construction method and expansion method of the dataset from the annotation method and data enhancement technology aspect. Analysis and discussion on the existing problems and application directions of deep learning-based intelligent identification of concrete surface defects are done.

Gap in the literature

However, automatic crack detection has witnessed numerous technological advancements, and the challenge of maintaining consistent efficiency remains. Despite being automated, current systems often struggle to accurately detect cracks in diverse and complex situations. Factors like different concrete textures, image noise, and varying lighting conditions, contribute to the complexity of these situations, resulting in potential false positives or negatives during crack detection. This emphasizes the need for a more adaptable and sophisticated system that can effectively address these challenges. Such a system should not only be resilient to environmental variations but also possess the ability to differentiate between cracked and intact concrete with a high level of precision.

Contributions

The main contribution is to design a crack classification system that can operate reliably under various conditions without compromising detection speed or accuracy, ultimately ensuring the safety and durability of concrete structures. This paper proposes a hybrid model for this purpose. The integration of Ridgelet Neural Networks (RNNs) with an advanced form of Human Evolutionary Optimization (AHEO) is a strategic approach to enhancing the precision and dependability of crack detection. The innovative application of AHEO to fine-tune and enhance the RNN model is a fundamental component of this research. By connecting the evolutionary principles embedded in AHEO, the optimization procedure becomes more efficient for the involved characteristics of crack formations in concrete infrastructures. Therefore, the main contributions can be highlighted as follows:

-

Designed a reliable crack classification system ensuring the safety and durability of concrete structures.

-

Proposed a hybrid model integrating Ridgelet Neural Networks (RNNs) with Advanced Human Evolutionary Optimization (AHEO).

-

Enhanced precision and dependability of crack detection through strategic integration.

-

Applied AHEO to fine-tune and optimize the RNN model effectively.

-

Addressed the unique characteristics of crack formations in concrete infrastructures.

Data collection

The evaluations of this study are based on the SDNET201816. It contributes to the advancement of maintenance strategies for concrete infrastructures worldwide17. Figure 1 illustrates a visual contrast between cracked and uncracked concrete pavement specimens for the SDNET2018 dataset. The images depict common conditions observed in concrete infrastructure.

Cracked samples (A) exhibit diverse crack patterns, likely caused by factors such as thermal expansion, load-induced stress, or material deterioration. These cracks vary in width and depth, indicating the level of damage18. Conversely, uncracked samples (B) remain undamaged with no visible signs of distress. This distinction is vital for training neural network systems to accurately differentiate and categorize the structural soundness of concrete surfaces.

Preprocessing

Median filtering

There are several advantages to using median filtering for image-based concrete crack detection. Firstly, it effectively reduces noise in images without blurring the edges of the cracks, ensuring accurate detection. Additionally, median filtering preserves the clarity of the crack boundaries, making it easier for algorithms to identify and analyze them, unlike other filters that may blur the edges. Moreover, median filtering is robust against outliers and impulsive noise, which can be mistaken for cracks. Furthermore, it is computationally simpler and faster, making it suitable for real-time crack detection applications. Therefore, applying median filtering enhances the quality of crack images, facilitating subsequent image processing or machine learning algorithms in accurately classifying and measuring the cracks.

The median filter functions by operating on a sliding pixel window, where the central pixel’s value is substituted with the median of the intensity values within that window. The user determines the window’s size, which directly impacts the filter’s effectiveness. This begins simplification based on examining a one-dimensional signal. The median filter process can be described as follows:

Take a window of size (\(n\)) centered at pixel (\(x(i)\)), with (\(i\)) representing the pixel’s index in the signal. The window will encompass a series of neighboring pixel values (\(x(i-k), \dots , x(i), \dots , x(i+k)\)), where (\(k =\frac{n-1}{2}\)).

-

Arrange the pixel values within the window in ascending order.

-

If (\(n\)) is odd, the median value (\(M\)) is the middle value of the sorted set. If (\(n\)) is even, (\(M\)) is typically the average of the two middle values.

-

Substitute the pixel value (\(x(i)\)) with the median value (\(M\)).

-

Mathematically, the median (\(M\)) of a value set (\(X=\left[{x}_{1}, {x}_{2}, \dots , {x}_{n}\right]\)) is defined as:

For a two-dimensional image, the process is similar but applied in both horizontal and vertical directions. The window moves across the image, considering a neighborhood for each pixel, sorting the values, and calculating the median to replace the original pixel value.

This filtering method is particularly beneficial for maintaining sharp edges in images, crucial for tasks like crack detection in concrete, as it avoids blurring edges like linear filters. Figure 2 illustrates the application of median filtering for noise reduction.

Contrast enhancement

Within the present research, Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) has been employed for contrast enhancement of the input images. The CLAHE is a sophisticated technique employed to enhance the contrast of images. This method proves particularly beneficial in accentuating local contrast and revealing intricate details that may not be discernible in the original image. The CLAHE algorithm operates by partitioning the image into smaller, contextual regions referred to as tiles. Subsequently, it independently applies histogram equalization to each tile. To mitigate the issue of excessive amplification of noise, a prevalent concern with conventional adaptive histogram equalization (AHE), CLAHE incorporates a contrast limit into the histogram equalization procedure. In the following, the steps of the CLAHE have been explained:

Image segmentation involves dividing the input image (\(I\)) into non-overlapping tiles (\({T}_{i,j}\)), where (\(i\)) and (\(j\)) are the tile indices.

Histogram computation is performed for each tile (\({T}_{i,j}\)), resulting in a histogram (\({H}_{i,j}(k)\)) that represents the intensity levels within the tile.

To avoid amplifying noise, the histogram is truncated at a specified value (Clip Limit), with any excess being redistributed among other histogram bins.

The truncated histogram is then utilized to generate a Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) (\({C}_{i,j} \left(k\right)\)), which facilitates the mapping of old intensity values to new ones.

Following histogram equalization, neighboring tiles may exhibit discontinuities at their borders. Bilinear interpolation is employed to smooth out these discontinuities. The CDF utilized in CLAHE is mathematically represented as follows:

where, \(l\) is an intensity level, and \(k\) is the maximum intensity level in the tile \({T}_{i,j}\).

Figure 3 showcases several instances of contrast enhancement using the CLAHE-based method. The first image (A) represents the original image, while the second image (B) displays the image after undergoing contrast enhancement.

Applying CLAHE can improve the local contrast of pavement images, thereby enhancing the visibility of cracks. This enhancement facilitates the accurate identification and classification of cracks by subsequent image-processing algorithms or neural networks. By equalizing the contrast within concrete surface images, CLAHE ensures that cracks are more easily distinguishable from the surrounding material. This is crucial for the reliable detection of cracks in structural health monitoring systems.

Data augmentation

Data augmentation has a critical role in enhancing the efficacy of deep learning models, particularly in tasks like concrete crack detection in image classification. By augmenting the dataset with modified images, the model can improve its ability to generalize and adapt to different real-world scenarios. Convolution filters are used to modify the texture and quality of the images through convolution operations, enabling the model to recognize features and patterns regardless of high-resolution details.

Random erasure is another technique that simulates occlusion by randomly removing parts of the image. This helps the model identify features without relying solely on complete visual information, thereby improving its crack detection capabilities even when cracks are partially hidden. Color space transformations, achieved by altering RGB color channels, brightness, and contrast, introduce variations in the appearance of the images.

This mimics diverse lighting conditions, which is crucial for a model deployed in environments where lighting conditions significantly impact visibility. Geometric transformations, such as cropping, stretching, zooming, flipping, and rotating, introduce spatial and perspective changes that assist the model in detecting cracks regardless of their orientation, scale, and position within the image. By incorporating a variety of augmentations, a comprehensive training dataset is created, which is vital for developing a reliable crack detection system. These techniques combined enable the deep learning model to effectively handle the complexities of analyzing real-world concrete surfaces. Figure 4 illustrates some samples of image augmentation utilized in the detection of concrete cracks.

The incorporation of these techniques is crucial for enhancing the robustness of algorithms developed for crack detection. By integrating a broader range of data using these methods, the diversity of crack images can be expanded. Consequently, this allows the model to effectively adjust to unfamiliar data and improve its overall precision. By integrating these augmentation techniques, we can effectively train the Ridgelet Neural Network to identify concrete cracks with enhanced efficiency in real-world scenarios.

Ridgelet neural network

A Ridgelet Neural Network uses ridgelet functions as activation functions in its hidden layers, enabling it to effectively represent directional information in high-dimensional spaces and functions with hyperplane singularities. This unique feature makes it well-suited for approximating a variety of multivariate functions, especially those with spatial inhomogeneities.

Unlike traditional neural networks that use simpler activation functions like sigmoid or ReLU, the Ridgelet Neural Network employs a three-layer feed-forward structure with the ridgelet function in the hidden layer. This design enables the network to capture more intricate patterns and relationships in the data, making it mostly beneficial for myriad tasks, comprising high-dimensional data or directional patterns and features.

Ridgelet surpasses the traditional neural network by extending the strengths of wavelet to higher dimensions.

RNN enhances the directional sensitivity of neurons by incorporating additional scale and location in its directional description. A Ridgelet neural network can approximate a complete multi-variable function on a smaller scale. The Ridgelet transform offers a more adaptable structure, faster parallel processing speed, and greater fault tolerance and resilience due to its relatively fixed nature. Consider that Φ is a function from \({R}^{n}\) To \(R\), meeting the specified condition:

where, \(\widehat{\varphi }\) specifies the FT (Fourier transform) of \(\varphi\), and \(N\) signifies the environmental dimension of the load forecast process. In this condition, the Fourier transform for space \(A\) is achieved as follows:

where, \(U\) represents the Ridgelet orientation, \(Z(t)\) represents the input data or feature vector at time \(t\), \(b\) and \(a\), in turn, illustrate the position and the scale of the Ridgelet, \(\alpha\) represents the parameter of the Ridgelet in space \(A\), such that:

where, \(USM\) describes an \(N\)-dimenstional unit sphere space.

The predicted output equation can be generated by using Ridgelet functions as the base variable and decomposing the function \(y|y=f(x):{R}^{n}\to {R}^{m}\) into \(m\) projections \({R}^{n}\to R\), resulting in the successful attainment of the output.

where, \(K\) represents the hidden layers quantity.

The structure of an RNN arrangement is depicted in Fig. 5.

Based on Fig. 5, the prediction’s effectiveness is enhanced by utilizing the linear integration of the Ridgelets and weights (\({w}_{i}\)). The first step in the system of hybrid prediction is defining the variables of the Ridgelet Neural Network. To commence, the training instances are considered in the following manner:

The scalar Ridgelet variables are defined by the parameters \(a\), \(b\), and \(W\). The direction, which is the final parameter, is expressed as follows:

By assuming these variables as decision variables, the chief objective is to optimize the design of the Ridgelet Neural Network. The cost function is the MSE (Mean Squared Error) which should be minimized.

where, \({D}_{ij}\left(t\right)\) and \({O}_{ii}(t)\) describe the desired and the real output of the network. The real output of the network is achieved subsequently:

where, \(l=\text{1,2},\dots ,n\).

Therefore, the main objective is to provide an optimization technique to minimize the MSE from Eq. (9). This study uses a modified metaheuristic that is an advanced variant of human evolutionary optimization for this purpose.

Advanced human evolutionary optimization algorithm

One of the primary drivers is the considerable adaptableness of the evolution of humans and their capability to discover optimized solutions in complicated environments. This brilliant capability to thrive in and navigate serious conditions has led to the development of HEOA (Human Evolutionary Optimization Algorithm) as a meta-heuristic algorithm, enabling it to effectively pursue optimized solutions in complicated scenarios. The Chaotic Universe Theory provides a unique point of view regarding the evolution and origin of the world.

It proposes the world requires a precise primary condition or a specific formation event that gradually evolves through self-regulating phenomena and chaotic processes. The present concept inspires Chaos Mapping, specifically Logistic, which is integrated into the algorithm like an initialization method. By incorporating the theory of chaos into HEOA, this algorithm introduces an exploratory and active component into the optimality procedure. The procedure of evolution of humans is divided into two various phases: human improvement and exploration.

The present division clarifies the complex concept of the evolution of humans, and it implies a technical basis for understanding the growth of human communities. During the global exploration stage, primary individuals encountered novel environments and characteristics, depending on trial and error as well as adjustment to develop techniques to survive. Over time, they slightly accumulated skills and knowledge through exploration and response.

The present stage of global search and adjustment is in agreement with the early stages of human evolution, reflecting the inquisitive nature of our species. The phase of individual growth defines the slight construction of human communities and the appearance of various nations, social systems, and technologies. The growth of humans has been deeply stemmed from perception, education, and awareness of the world and the environment. By gathering and exchanging information, individuals have created a system of knowledge about their existence and the world around them.

The current algorithm classifies the community of humans into four various characters: leaders, searchers, followers, and losers. Leaders pursue greater individual growth based on current information, while searchers venture into unfamiliar areas. Followers observe the findings of leaders and assist the leaders on the trips.

Unsuccessful individuals who struggle to adjust have been excluded from the community, and the population is relocated to areas that foster human growth. All roles adopt various search techniques to uncover the optimal global solution. Two extra techniques, namely the Levy flight approach and the jumping approach, have been discovered to enhance the existing algorithm. The Levy flight method is widely employed in intelligent optimization algorithms as it improves algorithm performance. This approach enhances global search skills by suggesting random motions.

The jumping approach is inspired by image density methods that ensure the evolution of the research scenario. It utilizes a jumping method like compression to simplify global search and modification. The present distinct approaches cooperatively lead to the functionality and design of the current algorithm that enables it to shape the fundamental rules of the evolution of humans and efficiently tackle complicated optimality issues. In the following, we first explain the original Human evolutionary optimization algorithm (HEOA) and then, in subsection (5.6), the advanced version is explained.

Population initializing

To replicate the disorderly step at the commencement of the evolution of humans, the present algorithm adjusts the population employing the Logistic Chaos Mapping technique. The initialization equation for Logistic Chaos Mapping involves defining the size of the population (\(N\)) and the highest number of iterations (\(Maxiter\)), while the lower bound (\(l\)) and upper bound (\(u\)) establish the boundaries of the search space.

where, \(\alpha = 4\), \(i = 1, 2, \dots ,N,\) \({z}_{i}\) describes the \({i}^{th}\) iteration and \({z}_{i-1}\) describes the former iteration value, and \({z}_{i}\) describes chaotic Map to the solution space:

Human global search

Once initialization of the individuals has been accomplished, the subsequent stage involves calculating each solution’s fitness. During the accompanying trials, the global search stage was explained as the highest 25% of iterations. Once confronted with unfamiliar regions and constrained information, candidates desire to adjust a stable approach to probing in the phases of individual improvement. The formula is determined below:

The adaptive function is denoted by \(\beta\), while \(t\) indicates the present quantity of iterations. The term \(dim\) refers to the problem’s dimensionality or the complexity of the parameters comprised. \({Z}_{i}^{t}\) represents the current state, and \({Z}_{i}^{t+1}\) indicates the state after the next update. \({Z}_{finest}\) represents the best state found so far, and \({Z}_{mean}^{t}\) denotes the average state in the current population. The floor function represents rounding down. Levy denotes the Levy distribution, \({f}_{jmp}\) is the jump coefficient, and \(rand\) is a random stochastic value between 0 and 1.

Mean position \({{\varvec{Z}}}_{{\varvec{m}}{\varvec{e}}{\varvec{a}}{\varvec{n}}}^{{\varvec{t}}}\): The mean state of the present population, illustrated by \({Z}_{mean}^{t}\), has been computed employing the subsequent formula.

Adaptive function \(\beta\)

The adaptive function, denoted as \(\beta\), has been found to be responsible for adapting the variables on the basis of the current situation and iterations. This function elucidates the growing challenge of individually examining information, as well as the characteristics of a crowded environment, which are calculated using the following equation.

Levy distribution: which is utilized to replicate the intricate characteristics of information acquisition during the global search phase in humans and the individualized curved improvement. The equation for Levy distribution is determined as follows, with the value of \(\gamma\) set at 1.5.

Jumping

The individual’s global search process involves a technique of stimulated jumping through the collection and reformation of pictures, in order to enhance the distribution of search scenarios. This approach affects how the individual’s eye perceives a picture within an integration of local and overall structures that makes it comparatively resistant to the negative impact of particular local data. The current approach maintains the crucial features of the meta-data while spreading the exploration in several areas, hence enhancing search efficacy. The coefficient of jump, illustrated by \({f}_{J}\), computes the magnitude of the jump and has been determined in the following manner:

Development step of the individual

During the development stages of the individual, the current algorithm categorizes the individual’s community into four different personas: explorers, leaders, strugglers, and supporters. All personas adopt a cohesive exploration technique, collaborating to uncover the best possible solution globally. The particular exploration techniques for all personas have been explained as follows:

Leaders: which are individuals who possess a surplus of information and have been commonly located in optimum positions. In the carried out research, candidates in the top 4/10 of preadaptation have been chosen as leaders. The candidates begin expeditions to identify finer regions for personal growth, using their information. The current global search process has been executed using the prescribed formula.

where, \(Rn\) represents a random variable following a distribution that is normal. The function \({O}_{1,d}\) generates a row vector that has \(d\) components in a place that all elements are one, \(B\) represents the assessment value of the situation (where, B = 6/10), \(R\) is a stochastic variable that is between 0 and 1 and indicates the intricacy of the location involving the leaders.

Depending on the complexity of the location, the leader is going to decide on a proper search technique. The comfort of information retrieval, depicted by \(\omega\), slightly reduces as progress advances. The coefficient \(\omega\) has been calculated using the following equation:

Searchers: Searchers comprise a significant part of uncovering new territories to discover the finest solution in the solution space. During the process, candidates who rank in the top between 80 and 40% of the population based on benchmarks are chosen as explorers. The method used by explorers is represented by the following equation.

where, \({Z}_{worst}^{t}\) specifies the \({t}^{th}\) iteration’s minimum modified member position in the population.

Followers: In the course of the investigation, these individuals align themselves with the most adaptable leader and conform to their methods. Typically, around 90% to 80% of the population, based on the level of their adaptableness, become followers. The followers’ approach to searching can be described as:

where, \({Z}_{finest}^{t}\) Illustrates the position of the most modified candidate during iterations. \(Rd\) defines a random value in the range [1, d].

Losers: Individuals who remain in the population and have experienced the poorest adaptation are classified as losers. Those currently under-adapted individuals who are not suitable for society would be eliminated, and new individuals would be introduced by imitation in regions conducive to personal growth. The replenishment of the population has been depicted as follows:

Advanced version

To improve the exploration and exploitation aptitudes of the human evolutionary optimization algorithm, certain modifications need to be made in the initialization of agents, the creation of the triangular topological units, and the local aggregation function. The main objective is to strike a balance between expanding the search area (exploration) and concentrating the search around the most optimal solutions (exploitation). One approach to achieve this is by incorporating more advanced distributions during population initialization, which can increase the level of unpredictability and diversity in the algorithm.

To accomplish this, the opposition-based learning approach has been employed to generate the initial population as follows:

During the process, \(R\left(t\right)\) and \({R}_{opp}\left(t\right)\) have been analyzed and the optimal one is used for the next iteration.

Authentication of the algorithm

The Advanced Human Evolutionary Optimizer (AHEO) underwent a thorough validation process against a set of 20 state-of-the-art benchmarks. These benchmarks consisted of 10 CEC 2019 and 10 CEC 2021 test functions. The evaluation process was conducted meticulously as part of an annual assessment tournament that utilized the 100-Digit Challenge to measure algorithmic performance.

To ensure a comprehensive analysis, the CEC04-CEC10 functions were configured as 10-dimensional minimization challenges, with a range of [-100, 100], following the specifications set by the CEC benchmarks’ developers. These functions were subjected to rotational and shift transformations to assess the adaptability and robustness of the algorithms.

In a contrasting setup, the CEC01-CEC03 functions were presented in various dimensions, requiring a more nuanced approach to maintain equilibrium across the tests. Scaling was introduced as an optional parameter to further diversify the testing conditions.

To ensure the integrity of the results, especially for the CEC01 functions, quality assurance protocols were established to address the complexity introduced by an additional 1000 dimensions to certain functions.

The performance of AHEO was compared with other prominent optimization algorithms, including the Lévy flight distribution (LFD)19, Gaining-Sharing Knowledge-based algorithm (GSK)20, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)21, and Coronavirus Herd Immunity Optimizer (CHIO)22.

Each algorithm underwent 100 iterations, involving 50 agents in the process. The operational parameters for these algorithms were systematically documented in Table 1, enabling a transparent and fair comparison.

This section has been specifically crafted to provide a focused lens on the validation efforts that highlight the effectiveness of AHEO within the field of evolutionary computation.

The research included the computation of key metrics like average value and the standard deviation value. To conduct a thorough analysis, each algorithm was executed 20 times. The comparison of the proposed AHEO with other sophisticated metaheuristics is presented in Table 2. The outcomes of the latest algorithms on the CEC2019 benchmark are depicted in Table 2.

The study involved calculating important metrics such as the standard deviation and mean. To ensure a comprehensive analysis, all algorithms were run 20 times. Table 2 displays the comparative analysis of the proposed Modified Ideal Gas Molecular Movement algorithm against other advanced metaheuristics. The ultimate outcomes of the current algorithms on the CEC2019 benchmark are illustrated in the following table.

Table 2 provides a comparison of the performance of the AHEO algorithm with other advanced metaheuristics such as LFD, GSK, HHO, and CHIO on the CEC2019 benchmark. The table displays the standard deviation and average values for each algorithm’s performance across ten different test functions. AHEO demonstrates superior performance compared to other algorithms on most test functions, except CEC01 where it performs similarly to LFD and GSK. AHEO showcases better stability and consistency than its counterparts, as indicated by its lower standard deviation values on the majority of test functions. This indicates that AHEO is less affected by parameter settings and can effectively adapt to various problem scenarios. The success of AHEO can be attributed to its ability to strike an equilibrium between exploitation and exploration, retain valuable information from past searches, and thoroughly explore the solution space. The ultimate outcomes of the current algorithms on the CEC2021 benchmark have been illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3 presents the comparison results of the current algorithms on the CEC2021 benchmark. It displays the standard deviation (StD) and average (AVG) values of each algorithm’s performance across ten test functions. The proposed AHEO algorithm illustrates finer efficacy in comparison with other algorithms on most test functions. It particularly excels on CEC03, CEC04, CEC05, CEC06, CEC07, CEC09, and CEC10, while achieving secondary or tertiary rankings on the remaining three test functions. AHEO’s superiority can be attributed to its ability to effectively balance exploration and exploitation through two distinct populations.

Additionally, it utilizes a memory-based mechanism to retain valuable information from previous searches and efficiently explores the entire solution space with a dynamic neighborhood structure. In contrast, traditional optimization techniques employed by LFD, GSK, HHO, and CHIO may encounter difficulties in finding optimal solutions and getting trapped in local optima. The outcomes represented in Table 3 emphasize the competitive advantage of AHEO over state-of-the-art metaheuristics on the CEC2021 benchmark. This underscores its potential applicability in various fields such as engineering design, scheduling, and logistics planning.

Results and discussions

During the evaluation of the proposed system for early detection of concrete crack, a series of tests were conducted to assess its effectiveness. Various measurement indices were employed to quantify the model’s efficacy. Within the present part, the mathematical formulas for the measurement indices will be represented that have listed below:

A) Specificity: The specificity metric evaluates a model’s accuracy in identifying true negative situations. It calculates the proportion of true negatives (TNs) to the sum of false positives (FPs) and TNs:

B) Recall (Sensitivity): Sensitivity refers to the measure of how well a model detects genuine positive instances. It quantifies the proportion of true positives (TPs) to the sum of false negatives (FNs) and TPs:

C) Accuracy: Accuracy assesses the entire correctness of a model’s outputs. It determines the proportion of the sum of TPs and TNs to the sum of all instances:

D) Precision: Precision indicates the proportion of true positives (TPs) to the sum of all positive instances. It calculates the ratio of TPs to the sum of TPs and false positives (FPs):

where, True Positive as TP, True Negative is denoted as TN, False Positive as FP, and False Negative as FN.

The explained metrics offer valuable insights into the performance of the concrete crack detection model. By analyzing these indicators, researchers can determine how well the model can accurately detect this issue and distinguish them from other medical conditions.

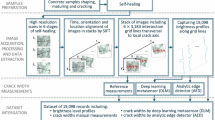

The simulation results are divided into three categories, each serving a specific purpose. The initial simulation evaluates the crack detection model’s effectiveness both before and after preprocessing steps. The second simulation involves a comparison of the recommended Ridgelet Neural Network (RNN) optimized by Advanced Human Evolutionary Optimization (AHEO), i.e., RNN/AHEO model with two other methods: a basic RNN model and an RNN model with traditional RNN/HEO model. This comparative analysis aims to demonstrate the superior performance of the suggested method. The third test focuses on evaluating the efficiency of the RNN/AHEO architecture compared to other current models. The simulations were carried out using Matlab R2020b for execution on Microsoft Windows 11. Testing is carried out on an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-9750H CPU clocked at 2.60GHz, paired with 16.0 GB of RAM, and an Nvidia GPU with 8 GB RTX 2070.

Analyzing the method before and after preprocessing

This section provides a comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of the RNN/AHEO model, both before and after implementing the random over-sampling technique. The main distinction observed in the study was that the initial results did not involve the over-sampling technique, whereas the subsequent results included the preprocessing steps. Table 4 illustrates the outcomes of concrete crack dataset recognition before and after the implementation of preprocessing steps.

Preprocessing has greatly improved the performance of our model with significant increases in accuracies, precisions, specificities, and sensitivities. In the end, the random oversampling technique helped us to balance the classes from the dataset leading to a more stable and reliable model. Based on this alone, accuracy improved from 96.301% to 99.665%, showing higher accuracy in correctly identifying both when cracks where present and not present. As a result, the precision rose from 97.989% to 99.194%, which indicated the model’s improved capability of retrieving all relevant instances. Similar behavior is seen with specificity that increased from 98.215% to 99.550%, showing that the model had a better identification of instances without cracks. The measures indicated that after preprocessing the model had a very high rate of sensitivity or 98.876% for denoting if any cracks were present. This emphasizes the strength of random oversampling in addressing class imbalances leading to better learning and ultimately better predictions by the model.

Analyzing the method based on the network architecture

An examination is necessary to determine the significance of the proposed RNN/AHEO model. This evaluation will involve a comparison with its simpler versions, specifically the RNN/HEO model, which lacks algorithmic changes, and the basic RNN architecture. The RNN/AHEO model can be seen as a streamlined version of the suggested approach as it does not incorporate the algorithmic adjustments of the AHEO algorithm. The RNN model serves as a foundational method that utilizes the original RNN model without any alterations. The accuracy of classification for the three methods was assessed through simulations of concrete crack detection. The classification analysis of the concrete crack Dataset has been represented in Table 5, where the performance of the RNN/AHEO model was contrasted with that of the RNN/HEO model and RNN.

The performance of the three models, RNN/AHEO, RNN/HEO, and RNN, showed significant variations, with the RNN/AHEO model demonstrating superior results. It achieved an accuracy of 99.665%, precision of 99.194%, specificity of 99.550%, and sensitivity of 98.876%. These impressive scores indicate that the RNN/AHEO model excelled in accurately identifying and categorizing cracks in the dataset. The integration of the AHEO algorithm into the RNN framework appears to greatly enhance the model’s capability for generalizing and predicting unseen data accurately.

Instead, the RNN/HEO model, lacking the algorithmic advancements of AHEO, performed decently but fell short of the RNN/AHEO model. It achieved an accuracy of 97.544%, precision of 97.308%, specificity of 97.614%, and sensitivity of 96.050%. The comparison between the RNN/HEO and RNN/AHEO models highlights the superior sophistication of the latter due to the additional algorithmic adjustments. The basic RNN model, without any modifications or enhancements, yielded the lowest results among the three. It had an accuracy of 84.731%, precision of 86.715%, specificity of 86.307%, and sensitivity of 86.940%.

While the underlying RNN model can detect patterns in the data, it is outperformed by more advanced versions. In conclusion, the outstanding performance of the RNN/AHEO model underscores the importance of combining advanced techniques like AHEO with traditional RNN architectures. The improvements in precision, recall, specificity, and sensitivity demonstrate the effectiveness of such hybrid models in complex tasks like concrete crack detection. Additionally, the results emphasize the significance of algorithmic enhancements in achieving top-notch metrics in machine learning projects.

Analyzing the method based on the comparative analysis

To perform a more comprehensive analysis of the proposed RNN/AHEO model in comparison to other recently mentioned methodologies, a comparative evaluation was carried out using several models that have been recently published. To provide a clear and concise discussion on the efficacy of the suggested RNN/AHEO model compared to the aforementioned methodologies, its results were compared with those of several recently published models, including deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN)10, CrackUnet8, R-CNN9, convolutional neural network (CNN)11, U-Net model12.

The current study utilized the SDNET2018 dataset to conduct simulations and evaluate the classification accuracy of the five techniques. The classification analysis of the RNN/AHEO model is presented in Table 6, where it is compared with other modern deep models. The comparison results of the distinct methods regarding categorization accuracy are depicted in Table 6.

The efficacy of the seven models for concrete crack diagnosis varies, with the RNN/AHEO model surpassing all others. It achieves the highest accuracy (99.665%), precision (99.194%), specificity (99.550%), and sensitivity (98.876%), indicating its proficiency in accurately identifying the presence and absence of cracks with minimal false positives and negatives. The CNN model closely follows, demonstrating strong performance with an accuracy of 98.191%, precision of 98.398%, specificity of 98.758%, and sensitivity of 97.599%.

However, it still falls short compared to the RNN/AHEO model, particularly in terms of accuracy and sensitivity. CrackUnet’s performance is slightly inferior to the CNN model, with an accuracy of 98.010%, precision of 97.675%, specificity of 97.587%, and sensitivity of 97.171%. R-CNN and DCNN models exhibit similar performances, with R-CNN having a slight advantage in accuracy (97.979%) and specificity (97.509%), while DCNN boasts slightly higher precision (96.058%). U-Net demonstrates the lowest performance among the models, with an accuracy of 97.212%, precision of 96.028%, specificity of 95.930%, and sensitivity of 96.480%.

The results conclusively highlight the superiority of the RNN/AHEO model in concrete crack detection, attributed to the synergy between the RNN architecture and the AHEO algorithm. These findings emphasize the importance of selecting the most suitable model architecture and enhancements for a given task to achieve optimal performance.

Conclusions

Timely identification of cracks in concrete structures is essential for proactive maintenance and restoration. The rise of digital imaging technology has led to the increasing use of machine learning algorithms to automate crack detection and classification. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated promise in image recognition tasks, they have limitations in handling data with intricate spatial relationships, like those in concrete structure images. Ridgelet Neural Networks (RNNs) offer a deep learning architecture that can better capture spatial relationships, making them a viable alternative to CNNs. Evolutionary optimization algorithms are commonly used to fine-tune deep learning model parameters by mimicking natural selection and evolution processes to find optimal solutions in vast parameter spaces. Advanced Human Evolutionary Optimization (AHEO) is a novel optimization algorithm that integrates human intelligence and domain expertise into the optimization process, resulting in enhanced efficiency and effectiveness. The objective of this research was to enhance and fine-tune an RNN model with AHEO to categorize and diagnose cracks in structures of concrete. Through the combination of RNNs and AHEO, the researchers aimed to produce a robust solution capable of precisely recognizing and categorizing cracks in concrete structures, ultimately enhancing the integrity and safety of infrastructure. After assessing the recommended approach, it was implemented on the SDNET2018 database. The results were compared with multiple advanced techniques, including deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN), CrackUnet, R-CNN, CNN, and U-Net model. The outcomes demonstrated that the suggested method performs better than them in different terms. Crack detection system design, even if it is creative, has its limitations. Since the accuracy and reliability of such systems are highly reliant on data quality and quantity, data gaps can impact them both. The model might also be challenged by changing lighting and weather conditions, which could impact detection precision. The working of RNNs along with AHEO increases the complexity and resource usage. Its universality is also limited because it may not apply to all forms of fracture or structural materials, other than concrete. Regular maintenance and upgrades are resource-intensive and are critical for system effectiveness. Future additions could include augmenting data gathering to better represent higher variety, higher-quality pictures for various conditions, system optimization for real-time usage, and/or application to asphalt or metallic substances. IoT technology enables ubiquitous monitoring and automatic data collecting, which is likely to improve infrastructures concerning maintenance upkeep. Research into reducing computing requirements without sacrificing accuracy and relying on advanced environmental mitigation methods may also aid performance. Such intuitive user interfaces and visualization tools would not only make the system more accessible to practitioners, but they would also serve the practical needs of practitioners. Khan says that these future additions would help strengthen the classification of fractures, making the concrete structures safe and durable.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the kaggle website: https://www.kaggle.com/aniruddhsharma/structural-defects-network-concrete-crack-images/code.

References

Duan, F. et al. Model parameters identification of the PEMFCs using an improved design of crow search algorithm. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47(79), 33839–33849 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Optimal economic scheduling of microgrids considering renewable energy sources based on energy hub model using demand response and improved water wave optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 55, 105311 (2022).

Roujin Mousavifard, M.A., Razmjooy, N. & Alizadeh Y. Optimal Design of Functionally Graded Steels Using Multi-objective Ant Lion Optimizer. in The 27th Annual International Conference of Iranian Society of Mechanical Engineers-ISME2019. (2019).

Park, S. E., Eem, S.-H. & Jeon, H. Concrete crack detection and quantification using deep learning and structured light. Constr. Build. Mater. 252, 119096 (2020).

Guo, P., Meng, W. & Bao, Y. Intelligent characterization of complex cracks in strain-hardening cementitious composites based on generative computer vision. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134812 (2024).

Bayar, G. & Bilir, T. A novel study for the estimation of crack propagation in concrete using machine learning algorithms. Constr. Build. Mater. 215, 670–685 (2019).

Deshpande, A. et al. Deep learning as an alternative to super-resolution imaging in UAV systems. Imag. Sens. Unmanned Aircraft Syst. 2, 9 (2020).

Zhang, L., Shen, J. & Zhu, B. A research on an improved Unet-based concrete crack detection algorithm. Struct. Health Monit. 20(4), 1864–1879 (2021).

Hacıefendioğlu, K. & Başağa, H. B. Concrete road crack detection using deep learning-based faster R-CNN method. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 46(2), 1621–1633 (2022).

Iraniparast, M. et al. Surface concrete cracks detection and segmentation using transfer learning and multi-resolution image processing. Structures 54, 386 (2023).

Laxman, K. et al. Automated crack detection and crack depth prediction for reinforced concrete structures using deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 370, 130709 (2023).

Nyathi, M. A., Bai, J. & Wilson, I. D. Deep learning for concrete crack detection and measurement. Metrology 4(1), 66–81 (2024).

Kirthiga, R. & Elavenil, S. A survey on crack detection in concrete surface using image processing and machine learning. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 9(1), 15 (2024).

Amirkhani, D. et al. Visual concrete bridge defect classification and detection using deep learning: A systematic review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25, 10483 (2024).

Zhang, J., Xu, Y. & Lu, D. Intelligent detection of concrete apparent defects based on a deep learning-literature review, knowledge gaps and future developments. Ceram. Silikáty 68(2), 252–266 (2024).

Dorafshan, S., Thomas, R. & Maguire, M. SDNET2018: An annotated image dataset for non-contact concrete crack detection using deep convolutional neural networks. Data Brief 21(1664–1668), 2018 (2018).

Dorafshan, S., Maguire, M. & Chang, M. Comparing automated image-based crack detection techniques in the spatial and frequency domains. in 26th ASNT Research Symposium. (2017).

Mahjoubi, S. et al. Identification and classification of exfoliated graphene flakes from microscopy images using a hierarchical deep convolutional neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105743 (2023).

Houssein, E. H. et al. Lévy flight distribution: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 94, 103731 (2020).

Mohamed, A. W., Hadi, A. A. & Mohamed, A. K. Gaining-sharing knowledge based algorithm for solving optimization problems: A novel nature-inspired algorithm. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 11(7), 1501–1529 (2020).

Heidari, A. A. et al. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 97, 849–872 (2019).

Al-Betar, M. A. et al. Coronavirus herd immunity optimizer (CHIO). Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 5011–5042 (2021).

Funding

Beijing Vocational Education Reform Project (Project Approval Number: DG2022008). The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R305), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., M.A., K.A.A., F.A.B. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Ahmadi, M., Alnowibet, K.A. et al. Concrete crack detection using ridgelet neural network optimized by advanced human evolutionary optimization. Sci Rep 15, 4858 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89250-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89250-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Leveraging emerging technologies to address the crisis of aging concrete infrastructure

Journal of Infrastructure Preservation and Resilience (2025)