Abstract

Based on fuzzy sliding mode control, a control strategy is developed for the buckling suppression of a cantilever structure. Due to the laminated composite structure, shear effects on the dynamic behavior of the structure are incorporated into the development of the equations of motion. Subsequently, a second-order Galerkin discretization is applied to establish a two-dimensional nonlinear system for the cantilever structure. Numerical simulations demonstrate that a two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic model of the laminated composite structure is essential for precise buckling vibration estimations. Therefore, a new active control strategy for large-amplitude buckling suppression of a two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of a cantilever beam is established and implemented, effectively suppressing the large-amplitude buckling response in numerical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Composite materials have become ideal for manufacturing many structural components due to their high specific strength, high toughness, chemical resistance, and other beneficial properties. Such components are particularly suitable for multi-physics working environments1. Currently, composite cantilever beams, a typical mechanical structure, are widely used in marine2, mechanical engineering3, aviation4,5, aerospace6, and other fields. As is well known, the nonlinear dynamic behavior of cantilever structures, such as buckling vibration, has a significant impact on both the dynamic stability and safety of such wildly applied mechanical structures. Accordingly, studying the nonlinear dynamic responses and large-amplitude response suppression of laminated cantilever structures is of great significance for design optimization and industrial applications.

So far, scholars have studied the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of laminated cantilever beams. Based on the assumption of the Euler-Bernoulli beam, Zhang7 analyzed the chaotic motion of a cantilever beam subjected to axial and transverse excitation at the free end. Zhou et al.8 established an equation of motion for chaotic vibration of a multi-layer laminated buckled beam featuring a proof mass and an axially applied external excitation, using Euler-Bernoulli beam model. Apalara9 has proven the conditions for the exponential stability of a thermoelastic laminated beam, for which the equation of motion was derived under Timoshenko beam theory. Jun et al.10 proposed a dynamic stiffness method to investigate the free vibration of a laminated composite beam according to the higher-order shear theory. Amabili et al.5 proposed an improved higher-order shear theory to simulate the nonlinear responses of composite cantilever structures. It is worth noting that the above analyses have focused on one-dimensional cantilever beam systems. Furthermore, in 2023, one-dimensional systems are still acceptable in nonlinear dynamic analysis in particular situations, such as micro- or nano-cantilever mass sensors11 and cantilever beams in channel flow12.

However, multi-dimensional cantilever beam systems have been adopted by some scholars for accurate numerical simulation. Zhang et al.13 discussed the transverse nonlinear responses of a four-dimensional nonlinear systems modeling piezoelectric composite cantilever structures under lateral and in-plane excitation. Wang et al.14 discovered chaotic motion in a multi-dimensional vertical cantilever beam system. Jin et al.15 derived the nonlinear equation of motion for a shape memory alloy hybrid composite beam using the Hamilton principle and established a two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system with a second-order Galerkin discretization. In addition, Soares et al.16 found through mode comparison that the nonlinear analysis of two-dimensional systems for a flexible beam in channel flow is sufficient. It should be noticed that the large-amplitude vibration control of multi-dimensional systems was not mentioned in the above studies, such as a vibration control of a two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system.

For the sake of controlling the vibration of nonlinear systems, various control methods have been developed, including the force control approach7, Fuzzy control optimized by PSO17, and high-frequency base-excitation control18, among others. Among these control strategies, sliding mode control (SMC) is widely used in practical vibration suppression, often in combination with other control methods. SMC was proposed by Utkin in 199219. In 2019, SMC was applied in the closed-loop control of capacitive microstructures20; in 2020, Azizi21 adopted a sliding controller to control an ATMD system of an 11-story building; in 2021, Azizi and Mobki22 designed a sliding mode controller to achieve active control of a suspension system, reducing vibration in cars. To mitigate the impact of uncertain factors on nonlinear dynamic systems, traditional SMC was enhanced with fuzzy rules in 2006, leading to the development of fuzzy sliding mode control (FSMC), which was then implemented for the chaotic vibration suppression in a dynamic system subjected to unknown external disturbances23. In 2011, Yau et al.24 applied FSMC in the chaotic vibration control of a micro-electro-mechanical system. In 2016, Radgolchin et al.25,26 developed a multi-level adaptive fuzzy controller for beyond pull-in stabilization of electrostatically actuated microplates to realize smooth control action and better response specifications, and the proposed fuzzy controller proved to be effective and efficient in stabilizing the microplate beyond pull-in instability limit; in the same year, Arun Prasad et al.27 used FSMC for speed regulation of an electric motor, reducing speed variations under load conditions. In 2017, Zhou and Chen28 applied FSMC to suppress the vibration of spinning beams; later in this year, Rahmani29 proposed a model-free fuzzy sliding mode observer for the robust vibration control of a rotating carbon nanotube-reinforced composite cantilever beam. To achieve chaotic synchronization in a Sprott’s system, Kuo30 designed an adaptive FSMC-based controller, building on existing FSMC studies. In 2022, Singh et al.31 applied a fuzzy logic controller for the vibration control of a lumped parameter model, which was established based on a smart cantilever beam. Furthermore, in 2023, Ma et al.32 combined FSMC with ant colony optimization to reduce speed deviation in both compressors and pumps. Notably, the control methods mentioned above have been applied to manage nonlinear responses of one-dimensional nonlinear systems, while few strategies exist for buckling vibration suppression in a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of multi-layer composite cantilever structures (or other beam structures33,34). Hence, a control strategy may have to be demanded for buckling vibration control of a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of a laminated composite cantilever structure.

In the present study, corresponding to the buckling vibration of a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of a laminated composite cantilever structure, a control strategy is established based FSMC and then validated in numerical simulation. The nonlinear partial-differential governing equation for the investigated cantilever structure, subjected to external sinusoidal excitation, is derived using Hamilton’s principle and validated through non-dimensionalization. The second-order Galerkin method is applied to develop the corresponding two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system. To demonstrate the influence of the first two vibration modes on the actual buckling response of the studied cantilever structure, numerical analysis is performed. Finally, an active control strategy is developed and introduced to suppress the large-amplitude buckling response of the two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system.

Model establishment

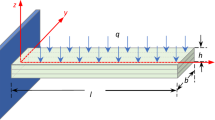

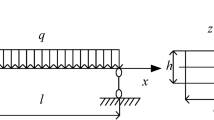

As shown in Fig. 1, a three-layer laminated composite cantilever beam structure is presented, and a Cartesian coordinate system \(\:oxyz\) is implemented to describe the displacement of the structure. The cross-section of the beam structure is uniformly rectangular; the structure’s total length, breadth, and height are denoted by \(\:l\), \(\:b\), and \(\:h\) respectively (as shown in Fig. 1 (a)), and the beam is composed of three layers and each layer features the same length, breadth, and height (as shown in Fig. 1 (a) and Fig. 1 (b)); the evenly distributed load, which is externally applied on the structure, is denoted by \(\:q\).

Without any deformation, the position of any point on the structure can be expressed as:

where the unit vectors along the \(\:x\)- and \(\:z\)-axes are denoted by \(\:\mathbf{i}\) and \(\:\mathbf{k}\), respectively.

The displacement of any point on the beam structure after deformation, according to Reddy’s higher-order shear effect assumption, can be expressed as:

where \(\:{c}_{1}=4/\left(3{h}^{2}\right)\); the displacements of a point on the middle-plane of the structure are denoted as \(\:{u}_{0}\) and \(\:{w}_{0}\), and the curvature due to Reddy’s higher-order shear effect is denoted by \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{x}\).

Then, based on Eq. (1) and Eq. (2), the kinetic energy of the cantilever structure, \(\:T\), can be derived as follows:

where \(\:\rho\:\) denotes the mass per unit volume of the cantilever structure.

Based on the expression of \(\:\mathbf{R}\) in Eq. (2), the geometric nonlinearity of the studied structure is expressed using the von Kármán type equation, as follows:

where, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{11}\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{13}\) represent the corresponding strains along the \(\:x\)- and \(\:z\)-axes, respectively.

Thus, based on Eq. (4-a) and Eq. (4-b), the potential energy of strain corresponding to the studied structure, \(\:U\), is derived as:

where the stiffness parameters in the \(\:x\)- and \(\:z\)-directions are denoted by \(\:{Q}_{11}\) and \(\:{Q}_{13}\), respectively.

The virtual work done by the evenly distributed load \(\:q\) and the damping force, \(\:W\), is given by:

where

and \(\:{q}_{0}\) in Eq. (7) denotes the magnitude of the sinusoidal external excitation, \(\:\omega\:\) represents the angular frequency of the excitation, and \(\:c\) is the damping coefficient of the cantilever structure.

With the application of Hamilton’s principle, we obtain:

where the Lagrangian fucntion \(\:L\) is expressed in Eq. (9) as follows

Considering the orthogonally symmetric laminated structure, we introduce Eq. (3), Eq. (5), and Eq. (6) into Eq. (8), and the partial differential equations of motion of the cantilever structure can be derived as follows:

where the specific expressions for \(\:{A}_{11}\), \(\:{K}_{2}\), \(\:{D}_{11}\), \(\:{F}_{11}\), \(\:{H}_{11}\), \(\:{A}_{55}\), \(\:{D}_{55}\), \(\:{F}_{55}\), \(\:{I}_{0}\), \(\:{I}_{4}\), and \(\:{I}_{6}\) can be found in Appendix, and

where \(\:i=0,\:1,\:2,\:\cdots\:,6\), and the stiffness parameters corresponding to the lower layer, middle layer, and upper layer of the cantilever structure are denoted by \(\:{Q}_{ij}^{\left(1\right)}\), \(\:{Q}_{ij}^{\left(2\right)}\) and \(\:{Q}_{ij}^{\left(3\right)}\), respectively, and the density parameters are correspondingly \(\:{\rho\:}^{\left(1\right)}\), \(\:{\rho\:}^{\left(2\right)}\) and \(\:{\rho\:}^{\left(3\right)}\).

The boundary conditions corresponding to Eq. (10-a), Eq. (10-b), and Eq. (10-c), can be established based on the previous study4, and presented as follows,

Because the current study focuses on the transverse vibration \(\:{w}_{0}\), both the axial vibration \(\:{u}_{0}\) and the rotational angle of the curvature \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{x}\) can be derived from Eq. (10-a), Eq. (10-b) based on the boundary conditions in Eq. (12-a), Eq. (12-b), Eq. (12-c), and Eq. (12-d), and \(\:{u}_{0}\) and \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{x}\) can be expressed as follows

With the introduction of both Eq. (13-a) and Eq. (13-b) into Eq. (10-c), it can be derived as follows,

+\(A_{{11}} \frac{{\partial \:w_{0} }}{{\partial \:x}}\frac{{\partial \:}}{{\partial \:x}}\left( { - \frac{1}{2}\left( {\frac{{\partial \:w_{0} }}{{\partial \:x}}} \right)^{2} + \frac{1}{{2L}}\int\limits_{0}^{l} {\left( {\frac{{\partial \:w_{0} }}{{\partial \:x}}} \right)^{2} dx} } \right)\)

+\(\:\left(-\left({A}_{55}-6{c}_{1}{D}_{55}+9{c}_{1}^{2}{F}_{55}\right)\frac{{\partial\:}^{2}{w}_{0}}{\partial\:{x}^{2}}+\left({A}_{55}-6{c}_{1}{D}_{55}+9{c}_{1}^{2}{F}_{55}\right)\frac{{F}_{11}{c}_{1}-{D}_{11}}{\left({A}_{55}-6{D}_{55}{c}_{1}+9{F}_{55}{c}_{1}^{2}\right)}\frac{{\partial\:}^{4}{w}_{0}}{\partial\:{x}^{4}}\right)\)

Therefore, with Eq. (11) introduced into Eq. (14), it can be derived that,

Non-dimensionalization

To validate and concisely express Eq. (15)13, the following dimensionless variables are introduced:

where \(\:I\) and \(\:{I}_{0}\) are expressed in Eq. (17) as follows,

Introducing Eq. (16) into Eq. (15), we obtain:

where A, B, C, D, F, G, and H are provided in Appendix. For brevity in the remainder of this study, \(\:{\stackrel{-}{w}}_{0}\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{t}\), and \(\:\stackrel{-}{q}\) will be denoted as \(\:{w}_{0}\), \(\:x\), \(\:t\) and, \(\:q\), respectively.

Series solutions

The function \(\:{w}_{0}\) can be expressed as a series of functions as follows:

.

Based on the cantilever boundary conditions, \(\:{\phi\:}_{n}\left(x\right)\) takes the following form:

where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}=1.875\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}=4.694\) in the case of a second-order Galerkin discretization.

Substituting Eq. (19) and Eq. (20) into Eq. (18) for a second-order Galerkin discretization, and the actual response \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\) at a specified point \(\:\left(x={x}_{\text{P}}=0.75\right)\) can be expressed based on Eq. (19) as follows:

where \(\:{T}_{1i}\) and \(\:{T}_{2i}\)\(\:\left(\text{f}\text{o}\text{r}\:i=1,\:2,\:\:\cdots\:,9\right)\) are provided in Appendix.

Large-amplitude buckling vibration

In this section, the large-amplitude buckling vibration at a specified point on the studied cantilever structure is presented.

The dimensions of the structure are as follows:

and \(\:q\) and \(\:c\) representing the applied load and the damping coefficient, respectively:

and the initial conditions are specified as follows:

The large-amplitude buckling vibration obtained from Eq. 12 and Eq. 13 at \(\:{x}_{\text{P}}=0.75\) is shown in Fig. 2. The dynamic response of this buckling vibration exhibits a displacement ranging from \(\:+3.116\) to \(\:-3.874\). Therefore, the absolute average amplitude of the discovered buckling vibration is about half of the range, which is nearly 3.5 times the height of the studied cantilever structure.

The first two mode vibrations are presented in Fig. 3: the displacement of \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) ranges from + 2.294 to -2.812, indicating that the absolute average amplitude of the buckling vibration for \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) is about 2.553; the displacement of \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) ranges from + 0.550 to -0.656, indicating that the absolute average amplitude of the buckling vibration for \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) is about 0.603.

Therefore, the influence of \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) on \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\) should be considered, and multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic systems for cantilever structures are necessary to achieve an accurate simulation of the buckling response. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, the large-amplitude buckling vibration requires a multi-dimensional system. Consequently, a control strategy based on the FSMC must be developed to suppress this dynamic behavior.

Control strategy

According to FSMC studies27,32, the dynamic systems to be controlled are given as follows:

and the desired reference system is presented as:

where \(\:1\le\:j\le\:n-1\), \(\:\mathbf{Y}={\left[{y}_{1}{y}_{2}\cdots\:{y}_{n}\right]}^{T}\in\:{\mathbf{R}}^{n}\), \(\:f\left(\mathbf{Y},t\right)\) represents the detailed form of \(\:{\dot{y}}_{n}\), \(\:d\left(\mathbf{Y},t\right)\) denotes an external uncertain disturbance applied on the dynamic system with \(\:\left|d\left(\mathbf{Y},t\right)\right|\le\:{B}_{\text{b}\text{o}\text{u}\text{n}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}\text{y}}\in\:{\mathbf{R}}^{+}\), and \(\:u\in\:\mathbf{R}\) represents the control input. Additionally, \(\:{\mathbf{Y}}^{o}={\left[{x}_{1}^{o}{x}_{2}^{o}\cdots\:{x}_{\kappa\:}^{o}\right]}^{T}\left(\kappa\:\le\:j\right)\) denotes the specified output in \(\:\mathbf{Y}\), and \(\:{\mathbf{X}}^{o}={\left[{x}_{1}^{o}{x}_{2}^{o}\cdots\:{x}_{\kappa\:}^{o}\right]}^{T}\) is the desired reference system response corresponding to \(\:{\mathbf{Y}}^{o}\).

However, it is observed that the active control formulated in Eq. (26) and Eq. (27) cannot be directly applied to multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic systems derived through Galerkin discretization, such as the cantilever structure represented in Eq. (22). It is also notable that the simulation results presented in Fig. 3, along with the previous studies12, emphasize the necessity of a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system, as in Eq. (22), for accurate buckling response analysis. Therefore, an active control strategy adapted from FSMC is established to control the buckling response observed in Eq. (22).

According to a nonlinear dynamic system defined below (i.e., Eq. (18)):

when \(\:U\) is introduced as the control input and \(\:{\Delta\:}F\left(w,\dot{w}\right)\) represents the uncertain disturbance externally applied to the dynamic system, Eq. (28) can be expressed as:

Applying the Galerkin discretization to Eq. (29) yields a system of second-order ordinary differential equations involving \(\:U\) and \(\:{\Delta\:}F\left(w,\dot{w}\right)\), as follows:

where \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{i}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\), \(\:{u}_{i}\), and \(\:{\Delta\:}{f}_{i}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\) represent the corresponding expressions of \(\:{\Phi\:}\left(w,\dot{w},t\right)\), \(\:U\), and \(\:{\Delta\:}F\left(w,\dot{w}\right)\) after applying the Galerkin discretization.

Specifically, \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{i}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\), \(\:{u}_{i}\), and \(\:{\Delta\:}{f}_{i}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\) after the introduction of the \(\:n\)th-order Galerkin discretization in Eq. (19) and Eq. (20) will lead to the following in Eq. (31), Eq. (32) and Eq. (33) below,

Thus, \(\:\mathbf{W}\) in Eq. (30) is defined in Eq. (34) shown as follows:

On the basis of Eq. (18) and Eq. (30), \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\) is then expressed as:

where \(\:{x}_{\text{P}}\) in Eq. (35) denotes the location of the selected point.

If a desired reference system is provided in Eq. (36) shown as follows:

then \(\:U\) can be described in Eq. (37) shown as follows:

where \(\:{U}_{eq}\) and \(\:{U}_{r}\) are defined in Eq. (38) shown as follows:

and \(\:\kappa\:\) is the coefficient defining the sliding surface in SMC, \(\:{k}_{fs}\) satisfies \(\:\left|{\Delta\:}F\left(w,\dot{w}\right)\right|<{k}_{fs}\in\:{\mathbf{R}}^{+}\), and \(\:{U}_{fs}\) is determined according to the fuzzy rule table presented in Table 128.

Corresponding to Table 1, the specific membership functions of \(\:{U}_{eq}\), \(\:\frac{d{U}_{eq}}{dt}\), and \(\:{U}_{fs}\) have been provided in Fig. 4a and b, following the previous studies23,27,28.

Following the active control strategy presented in Eqs. (29)-(38), buckling suppression for the vibration shown in Fig. 2 can be applied. According to Eq. (18) and Eq. (29), the established active control strategy can be implemented in Eq. (39) shown as follows:

Based on Eq. (30) and the second-order Galerkin discretization in Eqs. (21–22), this leads to:

where, through the specific Galerkin discretization, \(\:{u}_{1}\), \(\:{u}_{2}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{f}_{1}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\), and \(\:\varDelta\:{f}_{2}\left(\mathbf{W},t\right)\) are derived as:

Control application

Based on Eq. (40), Eq. (41) and Eq. (42), the suppression of the large-amplitude buckling vibration \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\) at the selected location on the studied cantilever structure is implemented in this section. To discuss the efficacy of the proposed control strategy in suppressing the vibration of the studied laminated composite cantilever structure, three different desired reference system responses have been presented in three cases based on the same parameters in Eq. (23), Eq. (24), and Eq. (25).

Case I) \(\:{w}_{r}=1.4\text{sin}\left(0.9931t\right)\)

With control applied at the time \(\:t=250\), the corresponding control parameters are as follows:

With the control applied, the large-amplitude buckling vibration previously shown in Fig. 2 has been suppressed, and the results are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7, and Fig. 8.

In Fig. 5, the maximum amplitude of the response at the location \(\:{x}_{\text{P}}=0.75\) has been reduced by \(\:59.41\%\), from \(\:3.495\) to approximately \(\:1.419\). The response is effectively suppressed and the amplitude is well synchronized with the desired sinusoidal response defined in Eq. (43). With the values of the control parameters \(\:\kappa\:\) and \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (43), the entire suppressing process shows that about 160 non-dimensional time units are required to get the buckling vibration finally suppressed.

In Fig. 6, a displacement comparison is presented to illustrate the efficacy of the applied control in detail. Although there exists only small difference in the amplitude between the actual response of the cantilever structure and the desired reference system response \(\:{w}_{r}\), the difference in the frequency is obvious. Hence, with the values of the control parameters \(\:\kappa\:\) and \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (43), only the amplitude synchronization is well achieved.

Figure 7 (a) and Fig. 7 (b) respectively illustrate the first and second mode vibrations of the beam. With the application of the control, both \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) are eventually suppressed, with their corresponding amplitudes significantly decreased. It should be noticed: after control achieved, the amplitudes of \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) have been reduced to \(\:1.047\) and \(\:0.096\) respectively, and the reduced amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) is only \(\:6.8\%\) of the suppressed amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\), which is \(\:1.419\) as shown in Fig. 5. Therefore, the first two mode vibrations are sufficient in the vibration control of the current case, since \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) can be omitted after control achieved.

Figure 8 shows the required control input. Initially, \(\:U\) rapidly increases to approximately \(\:-68\), which is the highest input required in the control process. During vibration suppression, the control input then gradually decreases to about \(\:-6.425\) and stabilizes once the actual response of the cantilever structure is synchronized with the desired response in Eq. (43). Comparing the values of \(\:U\) at the beginning and end of the control process, it is revealed: after the large-amplitude buckling response of the cantilever beam structure is suppressed, only a relatively low control cost is needed to maintain response suppression as the evenly distributed load \(\:q\) in Eq. (24) is applied. This demonstrates the efficiency of the developed control strategy.

Case II) \(\:{w}_{r}=1.0\text{sin}\left(0.9931t\right)\)

With control applied at the time \(\:t=250\), the corresponding control parameters are as follows:

With the control applied, the large-amplitude buckling vibration previously shown in Fig. 2 has been suppressed, and the results are presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11, and Fig. 12.

In Fig. 9, the maximum amplitude of the response at the location \(\:{x}_{\text{P}}=0.75\) has been reduced by \(\:68.35\%\), from \(\:3.495\) to approximately \(\:1.106\). The response is effectively suppressed and the amplitude is well synchronized with the desired sinusoidal response defined in Eq. (44). With the larger values of the control parameters \(\:\kappa\:\) and \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (44), the entire suppressing process shows that less than 10 non-dimensional time units are required to get the buckling vibration finally suppressed, indicating a much shorter synchronization process comparing with the 160-non-dimensional-time-unit process required in Fig. 5 in Case I).

In Fig. 10, a displacement comparison is provided to demonstrate the efficacy of the applied control. Besides the small difference in the amplitude between the actual responses of the cantilever structure and the desired reference system response \(\:{w}_{r}\), the difference in the frequency becomes smaller than that in Fig. 6 in Case I). Thus, with the increased values of the control parameters \(\:\kappa\:\) and \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (44), the frequency synchronization is improved in Case II).

Figure 11a and b respectively illustrate the first and second mode vibrations of the beam. With the application of the proposed control strategy, both \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) can be suppressed, with their corresponding amplitudes significantly suppressed. It should be noticed: after control achieved, the amplitudes of \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) have been decreased to \(\:0.825\) and \(\:0.069\) respectively, and the reduced amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) is only \(\:6.2\%\) of the suppressed amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\), which is \(\:1.106\) as shown in Fig. 9. Therefore, the first two mode vibrations are sufficiently enough in the vibration control of the current case, since \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) can be omitted after control achieved.

Figure 12 shows the control input demanded for vibration suppression. Firstly, \(\:U\) quickly increases to about \(\:-499\), which is the maximum control input demanded in the control process. During vibration suppression, the control input then rapidly decreases to about \(\:-237\) and stabilizes once the actual response of the cantilever structure is synchronized with the desired response. Comparing the values of \(\:U\) at the beginning and end of the control process, it is indicated: after the large-amplitude buckling response of the cantilever beam structure is suppressed, only a relatively low control cost is needed to maintain response suppression when the studied structure is being subjected to the evenly distributed load \(\:q\) in Eq. (24). However, to further suppress the amplitude of the studied structure from the previous amplitude reduction \(\:59.41\%\) to the current reduction \(\:68.35\%\), the maximum control input demanded has increased from \(\:-68\) to \(\:-499\), which is nearly 635% increase in the control input.

Case III) \(\:{w}_{r}=0.1\text{sin}\left(0.9931t\right)\)

With control applied at the time \(\:t=250\), the corresponding control parameters are as follows:

With the control applied, the large-amplitude buckling vibration previously shown in Fig. 2 has been suppressed, and the results are presented in Figs. 13, 14 and 15, and 16.

In Fig. 13, the maximum amplitude of the response at the specified location \(\:{x}_{\text{P}}=0.75\) has been reduced by \(\:96.85\%\), from \(\:3.495\) to approximately \(\:0.110\). The response is significantly suppressed and the amplitude is well synchronized with the desired sinusoidal response defined in Eq. (45). With the greatly increased value of \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (45), the entire suppressing process shows that less than 5 non-dimensional time units are required to get the buckling vibration finally suppressed, indicating a shorter synchronization process comparing with the 10-non-dimensional-time-unit process required in Fig. 9 in Case II).

In Fig. 14, a displacement comparison is shown to demonstrate the efficacy of the applied control strategy. Both the difference in the amplitude between the actual responses of the cantilever structure and the desired reference system response \(\:{w}_{r}\), and the difference in the frequency between the two, have become much smaller than those in Fig. 10 in Case II). Thus, with the significantly increased value of \(\:{k}_{fs}\) in Eq. (45), both the amplitude synchronization and the frequency synchronization have been achieved very well in Case III).

Figure 15a and b respectively illustrate the first and second mode vibrations of the studied cantilever beam. With the application of the proposed control strategy, both \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) are significantly suppressed. It should be noticed: after control achieved, the amplitudes of \(\:{w}_{\text{1,1}}\) and \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) have been decreased to about \(\:0.087\) and \(\:0.010\), and the reduced amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) is only about \(\:9.0\%\) of the suppressed amplitude of \(\:{w}_{\text{P}}\), which is \(\:0.110\) as shown in Fig. 13. Therefore, the first two mode vibrations are sufficiently enough in the vibration control of the current case, since \(\:{w}_{\text{2,1}}\) can be omitted after control achieved.

Figure 16 shows the control input needed for vibration suppression. Firstly, \(\:U\) quickly increases to about \(\:+730\), which is the maximum control input needed in the control process. During vibration suppression, the control input then quickly decreases to about \(\:+501\) and stabilizes once the actual response of the cantilever structure is synchronized with the desired response. Comparing the values of \(\:U\) at the beginning and end of the control process, it is learned: after the large-amplitude buckling response of the cantilever beam structure is suppressed, a relatively low control cost is needed to maintain response suppression when the studied structure is subject to the evenly distributed load \(\:q\) in Eq. (24). However, to further suppress the amplitude of the studied structure from the previous amplitude reduction \(\:68.35\%\) to the current reduction \(\:96.85\%\), the maximum control input need has increased from \(\:-499\) to \(\:+730\), which is almost 46% increase in the control input.

Conclusions

For the first time, an active control strategy has been implemented for the suppression of large-amplitude buckling in a composite cantilever beam structure, with higher-order shear effects considered in model establishment. Numerical simulations reveal a large-amplitude buckling response, demonstrating that not only is a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system required for accurate buckling response estimation of the structure, but a corresponding control strategy is also essential for vibration suppression in such structures. Therefore, based on the FSMC, an active control strategy was developed and implemented to suppress the large-amplitude buckling vibration of the studied structure. Through numerical simulations, both the effectiveness and efficiency of this control strategy in suppressing the buckling response have been thoroughly demonstrated. The primary conclusions of the study are presented as follows:

-

(1/5)

The large-amplitude buckling vibration of the two-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of the studied laminated composite cantilever beam structure can be reduced by up to 97% approximately, fully demonstrating the efficacy of the established control strategy in vibration suppression;

-

(2/5)

The amplitude of the suppressed vibration of the studied structure can be well synchronized with different desired reference amplitudes, fully demonstrating the efficacy of the established control strategy in amplitude synchronization;

-

(3/5)

The frequency of the suppressed vibration of the studied structure may be well synchronized with a desired reference frequency, indicating the influence of the established control strategy on frequency synchronization;

-

(4/5)

Both the first mode vibration and the second mode vibration, which are derived through a second-order Galerkin discretization, can be effectively suppressed corresponding to different reference response, demonstrating the efficacy of the established control strategy in the vibration suppression of a multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system;

-

(5/5)

Both the control efficacy shown in the three specified control cases in the present study, and the control input demanded in each of the corresponding control case, reveal the potential limitation of the established control strategy: the application of the proposed control may have to take into account the balance between the desired control efficacy and the corresponding practically-demanded control cost.

Future development

In the future development of the present study, the following potential research topics should be considered:

-

The established control strategy should be further validated in the vibration control of the multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system, which features the specific dimensions higher than the two-dimensional one studied in the present research. The corresponding research will not only contribute to the numerical studies on nonlinear vibration control of multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system, but also contribute to the possible practical application of the proposed control strategy in real world.

-

The convergence analysis of multi-dimensional nonlinear dynamic systems should be considered in the nonlinear vibration control of such multi-dimensional systems. Before the implementation of one control strategy in a multi-dimensional system, a proper dimension of the system may have to be decided to ensure the precision of the numerical simulation, while unnecessary calculation cost due to high dimensional systems can be reduced.

-

Maintain a balance between control cost and control efficacy. To facilitate the possible application of the proposed control strategy in practice, the control cost has to be optimized to fit the actuators available in engineering, while the control efficacy is not seriously compromised.

-

The critical buckling load of a cantilever structure subjected to transverse load, such as the one studied in the present research, should be studied. Such studies will not only facilitate the buckling vibration control, but may also demonstrate the differences between an axial-load induced buckling vibration and a transverse-load induced buckling vibration.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Chen, C. D. & Huang, B. F. A novel higher-order refined zigzag theory for static bending analysis in sandwich composite beam. Appl. Math. Model. 119, 586–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2023.03.011 (2023).

Liu, H., Qu, Y., Xie, F. & Meng, G. Vortex-induced vibration of large deformable underwater composite beams based on a nonlinear higher-order shear deformation zig-zag theory. Ocean Eng. 250, 111000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111000 (2022).

Pham, P. T., Kim, G. H. & Hong, K. S. Vibration control of a Timoshenko cantilever beam with varying length. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 20, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-021-0490-5 (2022).

Zhang, W., Sun, L., Yang, X. D. & Jia, P. Nonlinear dynamic behaviors of a deploying-and-retreating wing with varying velocity. J. Sound Vib. 332(25), 6785–6797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2013.08.006 (2013).

Amabili, M., Ferrari, G., Ghayesh, M. H., Hameury, C. & Zamal, H. H. Nonlinear vibrations and viscoelasticity of a self-healing composite cantilever beam: theory and experiments. Compos. Struct. 294, 115741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115741 (2022).

Jin, F., Zhao, C., Xu, P., Xue, J. & &Xia, F. Nonlinear eccentric bending and buckling of laminated cantilever beams actuated by embedded pre-stretched SMA wires. Compos. Struct. 284, 115211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115211 (2022).

Zhang, W. Chaotic motion and its control for nonlinear nonplanar oscillations of a parametrically excited cantilever beam. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 26(3), 731–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2005.01.042 (2005).

Zhou, L., Ji, P. & Chen, F. Chaos and subharmonic bifurcation of a composite laminated buckled beam with a lumped mass. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 147, 110933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110933 (2021).

Apalara, T. A. On the stability of a thermoelastic laminated beam. Acta Mathematica Scientia 39, 1517–1524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10473-019-0604-9 (2019).

Jun, L., Xiaobin, L. & Hongxing, H. Free vibration analysis of third-order shear deformable composite beams using dynamic stiffness method. Arch. Appl. Mech. 79, 1083–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-008-0276-8 (2009).

Darban, H. Size effect in ultrasensitive micro- and nanomechanical mass sensors. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 200, 110576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110576 (2023).

Soares, F. et al. Bifurcation analysis of cantilever beams in channel flow. J. Sound Vib. 567, 117951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2023.117951 (2023).

Zhang, W., Yang, J. H., Zhang, Y. F. & Yang, S. W. Nonlinear transverse vibrations of angle-ply laminated composite piezoelectric cantilever plate with four-modes subjected to in-plane and out-of-plane excitations. Eng. Struct. 198, 109501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109501 (2019).

Wang, G. X., Ding, H. & Chen, L. Q. Gravitational effects and mode interactions of vertical cantilever beams. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 123, 103493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2020.103493 (2020).

Jin, F., Zhao, C., Xu, P., Xue, J. & Lin, J. Nonlinear vibration of SMA hybrid composite beams actuated by embedded pre-stretched SMA wires with tension-bending coupling effect. J. Sound Vib. 568, 117964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2023.117964 (2024).

Soares, F. et al. A Galerkin formulation for the nonlinear analysis of a flexible beam in channel flow. J. Fluids Struct. 118, 103842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2023.103842 (2023).

Marinaki, M., Marinakis, Y. & Stavroulakis, G. E. Fuzzy control optimized by PSO for vibration suppression of beams. Control Eng. Pract. 18(6), 618–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conengprac.2010.03.001 (2010).

Sahoo, P. K. & Chatterjee, S. Vibrational control and resonance of a nonlinear tilted cantilever beam under multi-harmonic low and high-frequency excitations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 125, 107386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2023.107386 (2023).

Utkin, V. I. Sliding Modes in Control and Optimization. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-84379-2 (Springer, 1992).

Mobki, H., Jalilirad, M., Vatankhah Moradi, M. & Azizi, A. Multi input versus single input sliding mode for closed-loop control of capacitive micro structures. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0728-5 (2019).

Azizi, A. A case study on designing a sliding mode controller to stabilize the stochastic effect of noise on mechanical structures: residential buildings equipped with ATMD. Complexity 2020 (9321928), 10115520209321928 (2020).

Azizi, A. & Mobki, H. Applied mechatronics: Designing a sliding mode controller for active suspension system. Complexity 2021 (6626842). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6626842 (2021).

Yau, H. T. & Kuo, C. L. Fuzzy sliding mode control for a class of chaos synchronization with uncertainties. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 7(3), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2006.7.3.333 (2006).

Yau, H. T., Wang, C. C., Hsieh, C. T. & Cho, C. C. Nonlinear analysis and control of the uncertain micro-electro-mechanical system by using a fuzzy sliding mode control design. Comput. Math. Appl. 61(8), 1912–1916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2010.07.019 (2011).

Radgolchin, M. & Moeenfard, H. Development of a multi-level adaptive fuzzy controller for beyond pull-in stabilization of electrostatically actuated microplates. J. Vib. Control 24(5), 860–878. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546316653040 (2016).

Radgolchin, M., Moeenfard, H. & Ghasemi, A. H. A two-level adaptive fuzzy control algorithm for beyond pull-in stabilization of electrostatically actuated microplates. Proc. ASME 2016 Dynamic Syst. Control Conf. 2 (DSCC2016-9841). https://doi.org/10.1115/DSCC2016-9841 (2016).

Arun Prasad, K. M. & Unnikrishnan, A. Usha Nair. Fuzzy sliding mode control of a switched reluctance motor. Procedia Technol. 25, 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2016.08.167 (2016).

Zhou, L. & Chen, G. Fuzzy sliding mode control of flexible spinning beam using a wireless piezoelectric stack actuator. Appl. Acoust. 128, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2017.06.015 (2017).

Rahmani, B. Adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control for vibration suppression of a rotating carbon nanotube-reinforced composite beam. J. Vib. Control. 24 (12), 2447–2463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546316687937 (2018).

Kuo, C. L. Design of an adaptive fuzzy sliding-mode controller for chaos synchronization. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 8 (4), 631–636. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2007.8.4.631 (2007).

Singh, K., Kumar, R., Talha, M. & Narain, V. Vibration control of smart cantilever beam using fuzzy logic controller in Machines, Mechanism and Robotics. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. (eds (eds Kumar, R., Chauhan, V. S., Talha, M. & Pathak, H.) 1801–1812 (Springer, Singapore,. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0550-5_173 (2022).

Ma, Y., Liu, Y., Ding, H. & Yu, X. Hierarchical optimal intelligent battery thermal management strategy for an electric vehicle based on ant colony sliding mode control. ISA Trans. 143, 477–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.09.026 (2023).

Holmes, P. J. Bifurcations to divergence and flutter in flow-induced oscillations: a finite dimensional analysis. J. Sound Vib. 53(4), 471–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-460X(77)90521-1 (1977).

Abou Rayan, A. M., Nayfeh, A. H., Mook, D. T. & Nayfeh, M. A. Nonlinear response of a parametrically excited buckled beam. Nonlinear Dyn. 4, 499–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00053693 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NNSFC) through grant No.11602234, the talent scientific research fund of LIAONING PETROCHEMICAL UNIVERSITY (No. 2017XJJ-058), Liaoning Provincial Education Department Basic Scientific Research Project for Young Scientists (LJ212410148044), Liaoning Provincial Education Department Basic Scientific Research Project for Youth (LJ212410148060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. L.S.: Investigation, Data curation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision. X.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Review, Supervision. Y.Z.: Writing - review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. Y.D.: Data curation, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, J., Sun, L., Liu, X. et al. Buckling suppression of a cantilever structure with a modified fuzzy sliding mode control. Sci Rep 15, 4745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89259-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89259-8