Abstract

The electrical performance of high energy storage density materials has always been a research direction that has received high attention. This study used three typical high energy storage density materials and a traditional energy storage material to maximize the application effect of these materials. These materials include Graphene Oxide (GO), Polyaniline/Manganese Oxide Composite (PANI/Mno2) and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) and a traditional material aluminum electrolytic capacitor (AEC). This article conducted systematic experiments to evaluate the effects of these materials on circuit response, stability, energy storage efficiency, electrical response time and humidity. The experimental materials of this article were prepared by high-purity raw materials and strict quality tests were conducted to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the experimental results. The results showed that in terms of energy storage efficiency, GO performed the best, and its energy storage efficiency was 30% higher than that of traditional materials AEC. In terms of different temperatures, the circuit response of the PANI/MNO2 was the most stable, and the stability of the high temperature increased by 25%. In terms of different humidity, the GO conductivity rate reached up to 125 s/m, an increase of 47% over the initial value. In terms of electrical response time, GO had the shortest response time, with an average of 0.35 s, which was 85% faster than AEC’s 2.64 s. After comprehensive analysis of various data, the three high energy storage density materials have shown excellent performance in energy storage efficiency, electrical stability, and response speed, among which GO has the most outstanding performance. This study provides important data support for the selection and optimization of high-performance energy storage materials, verifies the excellent performance of high energy storage density materials under rapidly changing electrical conditions, and proves their wide applicability and huge potential in practical applications, laying a solid foundation for the promotion and application of industrial and technological fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional energy storage materials face many challenges in circuit applications, including low energy storage efficiency, poor cycling stability, and slow response time. With the popularization of electronic equipment and the increase in power demand, the demand for high-efficiency and stable energy storage materials has become increasingly urgent. Traditional materials cannot quickly adjust their energy storage status in a rapidly changing voltage environment, resulting in unstable circuit performance. This situation is particularly unfavorable for electronic devices that need to respond quickly and high-precision control. The use of traditional energy storage materials requires complex craftsmanship and expensive materials, which further limits the possibility of large-scale application1,2. This article selects high energy storage density materials, including Graphene Oxide (GO), Polyaniline/Manganese Oxide Composite (PANI/MnO2), and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT). The rationale for selecting only these three materials (GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT) is that they exhibit unique electrical characteristics and structures, maintaining excellent energy storage performance and stability under high voltage and fast charging and discharging conditions3,4. PANI/MnO2 consists of organic electrical polymer and inorganic oxides, which has a good mechanical stability. Instead, PEDOT is widely used in various electronic devices and energy storage systems due to its good conductivity and environmental stability5.

The organizational structure of this article is as follows: the first part introduces the research background and main contributions; the second part reviews relevant research work; the third part provides a detailed description of the experimental methods and testing equipment; the fourth part presents and discusses the experimental results, comparing the performance of high energy storage density materials with traditional materials in terms of energy storage efficiency, electrical response time, cycling stability, and environmental adaptability; the fifth part summarizes the research conclusions and proposes future research directions. Through systematic experimental verification and detailed data analysis, this article provides a scientific basis for the widespread application of high energy storage density materials in power systems, electronic devices, and energy storage fields.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

-

(1)

Systematic experimental verification and performance comparison: Through systematic experiments, the article conducts systematic experiments on three typical high energy storage density materials (Graphene Oxide, GO; Polyaniline/Manganese Oxide Composite, PANI/MnO2; Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) as well as a traditional energy storage material (aluminum electrolytic capacitor, AEC) were comprehensively evaluated for circuit response, stability, energy storage efficiency, electrical response time, and humidity effects.

-

(2)

Revealed the excellent performance of high energy storage density materials: The study found that GO performs best in energy storage efficiency, 30% higher than the traditional material AEC; in terms of electrical response time, the average response time of GO is only 0.35 s, 85% faster than AEC. In addition, PANI/MnO2 has the most stable circuit response at high temperatures, with the stability increased by 25%; and the conductivity of GO also significantly increases under different humidity conditions, reaching a maximum of 125 s/m, an increase of 47% from the initial value %.

-

(3)

Provides scientific basis and future research direction: Through detailed data analysis and experimental verification, the article provides scientific basis for the wide application of high energy storage density materials in the fields of power systems, electronic equipment and energy storage.

Related work

The circuit response is affected by excitation and the state of energy storage components, and the current and voltage undergo corresponding changes during the transient process. Therefore, when designing and optimizing the circuit, various factors need to be comprehensively considered. Wang, Hongxia, and others provided profound insights into charge transfer and chemical reaction kinetics through a detailed analysis of the circuit response of perovskite solar cells, providing direction for future research and device optimization6. Cui, Huachen found that by applying stress, the voltage response of materials in specific modes can be selectively suppressed, reversed, or enhanced. This manipulation enabled materials to exhibit different circuit response behaviors under specific conditions, providing greater flexibility and functionality7. Laschuk, Nadia O. measured circuit response through Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to gain a deeper understanding of the electrochemical properties and behavior of materials, providing scientific basis for material design and optimization. Circuit response analysis helped to reveal the performance of materials in practical applications, such as battery life, sensor sensitivity, and corrosion protection capabilities8. Liu, Shanliangzi demonstrated the superiority of biphasic Ga-In conductors in high conductivity, extremely high stretchability, and cycling stability by studying their performance in circuit response, providing a new solution for converting existing rigid circuit board components into flexible and stretchable forms9. Zhu, Kaichen demonstrated the potential and application prospects of 2D materials in high-performance integrated circuits by analyzing their performance in circuit response in detail. 2D materials are expected to play an important role in future electronic devices and integrated circuits10. Although these studies have made some progress in circuit response and experimental verification, most of them focus on the electrical characteristics of a single material, lacking comprehensive experimental comparison and analysis of multiple high energy storage density materials.

High energy storage density materials refer to substances that can store a large amount of energy. They have the characteristics of high energy density, high efficiency, low cost, and are widely used in multiple fields. Choi, Christopher demonstrated the importance of pseudocapacitive materials in high energy storage density applications by analyzing their electrochemical properties and potential applications in detail. Pseudocapacitive materials combined high energy density and high power density, making them suitable for developing electrochemical energy storage devices for fast charging11. Zhou, Cheng created a comprehensive database covering medium and high temperature phase change materials from 1956 to 2017, providing valuable resources for the design and application of future medium and high temperature energy storage systems, as well as the application of high energy storage density materials in medium and high temperature phase change energy storage, demonstrating their enormous potential in improving energy density and cycle efficiency12. Amiri, Azadeh proposed the potential of High Entropy Materials (HEMs) in energy storage and conversion technologies, particularly their application in improving the performance of electrochemical energy storage systems. By optimizing material design and exploring new combinations, HEMs are expected to play a key role in future electrochemical energy storage and catalytic applications13. Wang, Ge emphasized the importance of developing new lead-free high-temperature dielectric materials to promote the development of high energy/power density capacitor technology by analyzing in detail the advantages and potential of dielectric capacitors in high energy storage density applications14. Pan, Zhongbin et al. designed and prepared a novel high energy storage density (1 − x)(BNT–BST)–xKNN ceramic, which exhibited excellent energy storage and discharge performance. Especially, the 0.94(BNT–BST)–0.06KNN ceramic exhibited high efficiency and energy density under low electric fields, and remained stable within temperature and frequency ranges15. The research mainly focuses on the electrical properties of a single material, lacking comprehensive experimental verification and comparative analysis of multiple high energy storage density materials. This has led to a lack of comprehensive understanding of the performance of high energy storage density materials in practical applications. In addition, although some studies have mentioned the performance of materials in specific environments, there is still a lack of in-depth and systematic discussion on the specific effects of environmental humidity, temperature and other factors on the circuit response of high energy storage density materials.

Acquisition and detection of experimental materials

Material preparation

The preparation of GO is carried out using the improved Hummers method. 5 g of graphite powder are weighed and added to a mixed solution containing 180 milliliters of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) and 40 milliliters of phosphoric acid (H2PO4, 85%). The mixture is cooled in an ice bath to 0 degrees Celsius and stirred evenly. Then, 15 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) are slowly added, with the addition rate controlled to ensure that the temperature does not exceed 20 degrees Celsius. After potassium permanganate is completely dissolved, the reaction mixture is heated to 35 degrees Celsius and stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture is slowly poured into 2 L of ice water, and 50 milliliters of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) are gradually added to terminate the reaction. The reaction mixture is centrifuged multiple times, each time at 10,000 rpm (revolutions per minute) for 30 min, and washed with deionized water until the pH value of the washing solution approaches neutrality. The obtained graphene oxide suspension is freeze-dried for 48 h to obtain graphene oxide powder16.

PANI/MnO2 is prepared by chemical oxidation polymerization method. 2.5 g of aniline (C6H5NH2) monomer are weighed and dissolved in 250 milliliters of 1 mol/liter hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution, and the solution is cooled in an ice bath to 0–5 degrees Celsius. 2.5 g of ammonium persulphate ((NH4)2S2O₈) are slowly added as an oxidant and stirred to maintain temperature. 5 g of manganese dioxide (MnO2) nanoparticles are added to ensure their uniform dispersion in the polyaniline matrix. After the reaction lasted for 8 h, the product is separated by filtration and washed multiple times with deionized water until the pH value of the washing solution approaches neutrality. Finally, the product is vacuum dried at 60 degrees Celsius for 24 h to obtain PANI/MnO2 powder17.

PEDOT is prepared by chemical oxidation method. First, 1 gram of 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (C6H4O2S) monomer is weighted and uniformly dissolved in 50 milliliters of ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH). 2.5 g of ferric chloride (FeCl2) are weighed as oxidants and added in batches to the monomer solution. The reaction time is 24 h; the temperature is maintained at room temperature of 25 degrees Celsius; stirring is maintained. After the reaction is completed, the product is washed multiple times with ethyl alcohol and deionized water to remove unreacted monomers and by-products. Finally, the filter cake is dried at 60 degrees Celsius in a vacuum drying oven for 12 h to obtain pure PEDOT powder18.

Material impurity detection

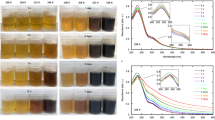

Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is utilized to analyze the chemical bonds and functional groups of materials to determine their structure and purity (FTIR was performed using Spectrum Software, version 10.5, URL: https://www.perkinelmer.com.). The prepared GO, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT powder are mixed with a small amount of KBr (potassium bromide), respectively. The mass ratio of samples to KBr is 1: 100. The mixture is ground and pressed into transparent sheets. The pressed sample slices are placed in the sample chamber of the FTIR spectrometer. The scanning range is set to 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Each sample is scanned 32 times to reduce noise19. The spectral data is collected through FTIR spectrometer software, and the infrared spectrogram of the sample is generated. The data is subjected to baseline correction and noise removal processing to ensure spectral clarity20. The details are shown in Fig. 1.

In Fig. 1, FTIR spectrogram of different materials are displayed. The X-axis represents the number of waves (Wavenumber), measured in cm−1; the Y-axis represents absorbance. GO shows an absorption peak of carbonyl group (C = O) at 2000 cm−1, and a broad absorption peak of hydroxyl (O-H) at 3400 cm−1. The spectrum of PANI/MnO2 shows characteristic absorption peaks of the benzene ring skeleton and MnO2, with absorption peaks near 2200 cm−1 corresponding to certain hydrogen bonds in PANI or byproducts during polymerization. A characteristic absorption peak is displayed at around 1600 cm−1, usually related to the vibration of the benzene ring skeleton. The absorption peak of PEDOT near 2200 cm−1 may be related to the polymer chain structure of PEDOT. The C = C stretching vibration peak is displayed at around 1500 cm−1. Through these characteristic absorption peaks, the presence and main components of the material are confirmed, and it is known that there are no obvious impurities in the relevant materials of this experiment. If impurities exist, additional absorption peaks appear outside the characteristic peaks, thereby affecting purity analysis.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) is used to analyze the thermal stability and composition of materials (TGA were collected using Pyris software, version number is Pyris 7.1, URL: https://www.perkinelmer.com.). Approximately 5–10 milligrams of GO, PANI/MnO2, and PEDOT powders are weighed to ensure uniform distribution of the samples in an aluminum sample tray. The sample disk is placed in the sample chamber of the TGA instrument and heated from room temperature to 800 degrees Celsius in an inert gas (such as nitrogen) atmosphere at a rate of 10 °C/min, and the mass change of the sample is recorded. Through TGA instrument software, the relationship curve between quality change and temperature is collected, and a TGA map is generated to record the initial mass, decomposition temperature, and remaining mass of the sample21. The details are shown in Fig. 2.

As shown in Fig. 2, the TGA curves of different materials are shown. The X-axis represents temperature, in degrees Celsius (°C); the Y-axis represents the weight% (%). GO undergoes partial decomposition between 200 and 300 °C, losing some oxygen-containing functional groups and resulting in a decrease in weight. PANI/MnO2 decomposes at higher temperatures (300–400 °C), and manganese oxide has high thermal stability. PEDOT undergoes decomposition between 250 and 350 °C, exhibiting a significant decrease in weight. From these thermogravimetric curves, it can be inferred that there are no obvious impurities in the relevant materials of this experiment. If impurities exist, additional quality loss occurs during the decomposition process, which affects purity analysis.

Experimental methods

This article uses a variety of testing methods to comprehensively evaluate the electrical performance of high energy storage density materials, including conductivity tests, capacitor tests and impedance tests. Each test method has its unique steps and data analysis methods. The conductivity test method measures the current of the sample by applying a voltage, and then calculates the conductivity using a formula, as shown in Formula 122.

In Formula 1, \(\:I\) is the current passing through the sample; V is the applied voltage; A is the cross-sectional area of the sample.

The method of testing capacitance includes applying AC (alternating current) voltage of different frequencies, measuring current response, and then calculating capacitance using the formula shown in Formula 223.

The method of testing impedance includes applying AC voltage to a known frequency, measuring the phase difference and amplitude of voltage and current, and calculating impedance using formulas. The formula is shown in Formula 324.

Experimental data acquisition and processing

Data acquisition device

A full set of experimental devices are used in this article, including electrical measurement systems, environmental control systems and data collection systems. The electrical measurement system includes power supply, function generator, current meter, voltage meter and oscilloscope. The power supply provides a stable DC (direct current) voltage with a range of 0–10 V and a precision of 0.01 V. The function generator generates a communication signal of different frequencies and amplitude, from 1 Hz to 1 MHz, with an amplitude of 0–10 V. The current meter measures the current of the sample with an precision of 0.01 mA. The voltage meter measured the voltage at both ends of the sample with an precision of 0.01 MV. The oscilloscope is used to record and display the transient voltage and current change in the circuit, and the bandwidth is 100 MHz.

The temperature control box, humidity controller and atmosphere controller constitute an environmental control system. The temperature of the experimental environment is controlled by the temperature control box, and its precision is ± 0.1 °C, and the range is -20 °C to 150 °C. The humidity controller is used to control the humidity of the experimental environment. The range is 0-100% humidity, and the precision is ± 2% humidity. The atmosphere controller is used to regulate the atmosphere in the experimental environment, which mainly includes the proportion of oxygen and nitrogen to ensure that the experiment is performed under specific atmosphere conditions. The relevant equipment is shown in Fig. 3:

The data acquisition system consists of high -precision data acquisition cards, computer and data processing software. The data collection card converts the analog signal in the electrical measurement system into digital signals, computer storage and processing data, data processing software analysis and display data. The data collection system can record the voltage, current, and environmental parameters during the experiment in real-time to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the data.

Data collection

Each sample of this experiment is strictly prepared and processed to ensure that their morphology and composition are consistent. The prepared GO, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT are connected to the experimental circuit. Before the experiment, all devices need to be calibrated to ensure that the data is accurate. The AC voltage of different frequencies and amplitude of the function is measured by the function generator to measure the current response of the sample under these conditions. Voltmeters and ammeters record and display transient voltage and current changes in the circuit to analyze the reaction speed and stability of materials under rapidly changing voltage conditions.

There are three steps collected in this article: measuring the conductivity, capacitance and impedance. Conductivity, capacitance, and response time were measured using a CH Instruments 600E electrochemical workstation. The conductivity data shows the conductive capacity of the material under the DC voltage condition. The higher conductive rate material can transmit the current more effectively. The capacitor data indicates the energy storage capacity of the material under AC voltage conditions. Using high-precision data collection card, the data collection process converts the analog signal to a digital signal and transmits it to the computer. The use of data collection software can monitor and record experimental data in real-time to ensure that the data is complete. Table 1 shows the data collection results of Go, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT.

Table 1 shows the electrical performance data of the three high energy storage density materials: conductivity, capacitance and impedance. They perform well under different voltage and frequency conditions. The table records the data of each material into five sets of different experimental conditions. Table 1 presents the electrical performance data for three high energy storage materials—GO, PANI/MnO2, and PEDO under various experimental conditions. The table records key parameters: voltage, current, conductivity, frequency, capacitance, and impedance. For GO, at a voltage of 0.1 V, the conductivity reaches 7500 S/m, while the impedance is 1.79 Ohm. As voltage increases to 0.5 V, the conductivity decreases to 1220 S/m, with the impedance rising to 12.82 Ohm. PANI/MnO2 shows similar trends, with its highest conductivity (6500 S/m) at 0.1 V, while at 0.5 V, conductivity decreases to 1100 S/m, with impedance increasing to 14.29 Ohm. PEDOT, on the other hand, shows a slightly lower conductivity, peaking at 5800 S/m at 0.1 V, and impedance at 1.89 Ohm. At 0.5 V, its conductivity reduces to 1340 S/m, and impedance increases to 13.16 Ohm.

Data preprocessing

The data processing steps of this article include noise filtering, baseline correction and data smooth.

The original data is filtered out by noise, and the digital filter removes high-frequency noise in the data. The low-pass filter used in this article has a transmission function, as shown in Formula 425,26.

In Formula 4, \(\:f\) is the frequency; \(\:{f}_{c}\) is the cutoff frequency; n is the order of the filter.

In order to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data, the baseline correction usually uses the baseline function of the polynomial and fitting to reduce the baseline drift in the data27.

In Formula 5, \(\:B\left(x\right)\) is the baseline function; \(\:{a}_{i}\) is the fitting coefficient; \(\:x\) is the data point.

After processing the data, the data smooth is to reduce the fluctuation of data by using a moving average or other smoothing algorithms. Formula 6 shows the smooth function of the mobile average algorithm28.

In Formula 6, \(\:S\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the smoothed data point; \(\:{y}_{i+j}\) is the original data point; \(\:m\) is half of the smooth window.

Data fitting

After the data pre-processing is completed, the processing data needs to be further fitted and analyzed. Data fitting is to describe the electrical performance of the material by using the appropriate electrical model, further understand the behavior characteristics of the material under different conditions, and verify the reliability of the experimental results. For the conductivity data, this article uses the Drude model, which is shown in the Formula 729.

In Formula 7, n is the carrier concentration; e is the electronic charge; \(\:\tau\:\) is the scattering time; \(\:{m}^{*}\) is the effective quality; \(\:\omega\:\) is the angular frequency. By fitting conductivity data, the free carrier concentration and mobility of the material were analyzed.

For capacitance data, the RC (resistor–capacitor) equivalent circuit model is used for fitting. The capacitance formula of the RC equivalent circuit model is shown in Formula 830.

In Formula 8, \(\:Z\left(\omega\:\right)\) is impedance; \(\:j\) is an imaginary unit; \(\:\omega\:\) is the angular frequency; \(\:C\) is the capacitance; R is the resistance. By fitting capacitance data, the dielectric constant and energy storage capacity of the material are analyzed.

For impedance data, the complex impedance model is used for fitting. The formula for the complex impedance model is shown in Formula 931.

In Formula 9, \(\:R\) is the resistance; \(\:j\) is an imaginary unit; \(\:\omega\:\) is the angular frequency; \(\:L\) is inductance; \(\:C\) is the capacitance.

Table 2 shows the results of GO, PANI/MnO2, and PEDOT after data preprocessing and fitting.

In Table 2, for GO, its conductivity exhibits high stability under different voltage conditions. At 0.1 V, the treated conductivity is 7350 S/m, indicating good conductivity of GO at low voltage. As the voltage increases, the conductivity slightly decreases, reaching 1196 S/m at 0.5 V. The capacitance value gradually decreases with the increase of voltage, reaching 9.13e-3 F at 0.1 V and 3.99e-4 F at 0.5 V, indicating that the energy storage capacity of GO is weakened at higher voltages. The impedance value varies greatly at different voltages, increasing from 1.82 Ohm at 0.1 V to 12.50 Ohm at 0.5 V, indicating a significant increase in GO impedance at higher voltages. The superior stability of GO may be related to its unique two-dimensional structure, high specific surface area, and excellent conductive properties, which together enable it to maintain relatively stable conductivity when temperature changes.

For PANI/MnO2, its conductivity is 6370 S/m at 0.1 V, showing high conductivity, and the conductivity drops to 1078 S/m at 0.5 V. The capacitance value varies greatly at different voltages, decreasing from 6.89e-3 F at 0.1 V to 3.58e-4 F at 0.5 V, indicating a weakened energy storage capacity of PANI/MnO2 at higher voltages. The impedance value increases from 1.89 Ohm at 0.1 V to 14.29 Ohm at 0.5 V, indicating a significant increase in the impedance of the material at higher voltages. For PEDOT, its conductivity is 5690 S/m at 0.1 V, demonstrating good conductivity. At 0.5 V, the conductivity drops to 1320 S/m. The capacitance value varies less under different voltages, decreasing from 7.92e-3 F at 0.1 V to 3.78e-4 F at 0.5 V. The impedance value increases from 1.85 Ohm at 0.1 V to 12.82 Ohm at 0.5 V, indicating a significant increase in PEDOT impedance at higher voltages.

Experimental results

Comparison of energy storage efficiency

In the comparison experiment of energy storage efficiency, this article tests three high energy storage density materials (GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT) and traditional AEC32. The experiment uses the energy storage efficiency of different materials to measure their performance. In order to ensure the reliability and repetitiveness of the data, the number of samples of each material must not less than 9.

The calculation of energy storage efficiency is based on the energy storage and release ability of the material during the charging and discharging process. Specifically, the energy storage efficiency (\(\:{\upphi\:}\)) can be calculated by the following formula:

Among them, discharge energy and charging energy respectively represent the energy that the material can store and release during the discharge and charging processes.

In terms of statistical analysis, this article uses mean values and error bars to display experimental results. The mean reflects the average level of energy storage efficiency for each material, while the error bars show the range of fluctuations in the experimental data, providing additional information on the reliability of the data. By calculating the standard error (SE) and performing statistical analysis methods such as t-test (t-test), this article further verified the importance of the found results. SE measures the degree of deviation between the sample mean and the population mean, while the t test is used to compare whether there is a significant difference in the means of two sets of data. The application of these statistical methods enhances the credibility of the experimental conclusions and ensures that the observed differences in energy storage efficiency are statistically significant.

The details are shown in Fig. 4.

In the Fig. 4, the energy storage efficiency comparison of each material under constant voltage is displayed. The column diagram shows the energy storage efficiency of each material and adds an error bar to display the error range of the experimental data. GO has the highest energy storage efficiency, reaching 95%, indicating that it has an advantage in charge storage, which is related to its higher ratio area and excellent conductive performance. The energy storage efficiency of PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT is also high, 90% and 85%, respectively, indicating that they show good stability and efficient charge transmission capabilities in the energy storage process. The energy storage efficiency of traditional materials AEC is 80%, but the efficiency is reduced after multiple charging and discharge. The error bar in the figure shows that the data of high energy storage density materials in the experiment fluctuate less, which indicates that experimental repetitiveness and data reliability are higher.

Impact of different temperatures on circuit response

In this section, the effects of different temperatures on the response of material circuits are studied. The conductivity of the three high energy storage density materials (GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT and traditional materials AEC) is tested at low, room and high temperature conditions. The experimental conditions are strictly controlled to ensure that the impact of temperature on the conductivity can truly reflect the performance changes of the material. The details are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5 shows the conductivity of Go, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT and AEC changes under different temperature conditions. The line chart shows the changes in conductivity of each material at multiple temperature points from − 20℃ to 100℃, reflecting the influence of temperature on material conductivity. As shown in the figure, the conductivity of GO at low temperature (-20℃) is 70 S/m. As the temperature increases, the conductivity gradually increases to 135 S/m at 100℃. This indicates that the conductivity of GO decreases less at low temperatures, while it significantly increases at high temperatures, exhibiting good temperature stability. The conductivity of PANI/MnO2 is 60 S/m at low temperature and gradually increases to 125 S/m at 100℃ with increasing temperature. The conductivity of PEDOT at low temperature is 55 S/m, which gradually increases to 120 S/m at 100 ℃ as the temperature increases. The conductivity trend of these two materials at different temperatures is similar to that of GO, but the overall conductivity is slightly lower than GO. However, the conductivity of traditional material AEC under low temperature conditions is only 40 S/m, which gradually increases to 105 S/m at 100℃ as the temperature increases. Compared with materials with high energy storage density, AEC exhibits significant changes in conductivity under low and high temperature conditions, indicating a higher sensitivity to temperature changes and poorer temperature stability33,34,35. The conductivity of GO, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT all increase in the temperature range of 20 to 30 ℃. As the temperature increases, more free charge carriers are released (for example, bound charges become free charges through thermal excitation). This increases the charge carrier concentration in the material and thus increases the conductivity. As a traditional material, the change in conductivity of AEC with temperature may be affected by different physical and chemical processes, but it also shows an increasing trend overall.

Comparison of capacitance stability

In order to evaluate the cycling stability, this article tests three high energy storage density materials (GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT, and AEC) capacitance retention rates through multiple charging and discharge cycles28. The experiment is performed under constant voltage conditions, and the capacitance retention rate of each material is recorded after the charging and discharge cycle of different times. The results are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 shows the heat map of AEC, GO, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT’s capacitance retention rates after multiple charging and discharge circles. The shades of color reflect the capacitance retention rates of different materials. It can be seen from the figure that after 100 charging and discharge cycles, the capacitance retention rate of GO remains at 89%, which indicates that its excellent cycling stability is maintained; the capacitance retention rate is maintained at 87%. The capacitance retention of traditional materials AEC shows obvious attenuation, which indicates that its stability is poor.

Comparison of electrical response times

In the comparison experiment of electrical response time, the response time of three high energy storage density materials (GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT and AEC) is measured using a AC voltage of different frequencies. The experiment aims to evaluate the electrical response ability of these materials at different frequencies to determine their applicability under rapidly changing electrical conditions. The detailed diagram is shown in Fig. 7.

From Fig. 7, it can be seen that the response time of each material varies with frequency, reflecting the adaptability of the material under rapidly changing electrical conditions. The response time of GO remains at the lowest level under both low-frequency and high-frequency conditions, demonstrating extremely fast electrical response capability. As the frequency increases, the response time of GO gradually increases from 0.05 s to 0.53 s, and it can still maintain an extremely fast response time under high-frequency conditions, suitable for rapidly changing electrical applications. The response time of PANI/MnO2 gradually increases with the increase of frequency, demonstrating good electrical response ability. PANI/MnO2 responds to 0.1 s under low-frequency conditions, and when the frequency increases to 100 Hz, the response time increases to 1.4 s. Under high-frequency conditions, it also has better electrical performance. PEDOT’s response time is very large, from 0.15 s to 1.6 s, showing good electrical response characteristics. PEDOT has a good response time under low-frequency and high-frequency conditions, which makes it an ideal choice for extensive electrical applications. AEC’s response time is 0.3 s under low-frequency. As the frequency increases, the response time gradually increases to 2.64 s. Compared with the three high energy storage density materials, AEC has the longest response time, and shows slower electrical response capabilities. Therefore, it is not suitable for rapid changes.

Influence of environmental humidity on electrical performance

In the experiments of the effects of electricity performance and environmental humidity in this section, three types of high energy storage density materials GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT and traditional materials AEC are tested. Under different humidity conditions (20% RH, 40% RH, 60% RH, 80% RH, 100% RH), the conductivity changes of each material are recorded to obtain electrical performance in different humidity environments. The details are shown in Fig. 8.

In Fig. 8, the scatter plot matrix of conductivity for GO, PANI/MnO2, PEDOT, and AEC under different humidity conditions is displayed. In Fig. 8, the horizontal axis represents different humidity conditions, usually expressed as a percentage of relative humidity (RH), such as 20% RH, 40% RH, 60% RH, 80% RH, and 100% RH. The vertical axis shows the conductivity values of various materials under different humidity conditions. Conductivity is usually measured in Siemens per meter (S/m), which is an indicator of the material’s ability to conduct electricity. The scatter plot matrix displays the changes in conductivity of various materials under different humidity conditions. GO’s conductivity is distributed in different humidity conditions, but as the humidity increases, its conductivity gradually increases. The data point in the scatter plot matrix shows the conductivity distribution trend of Go under different humidity conditions. This shows that under high humidity conditions, GO’s conductivity is higher. The conductivity of PANI/MnO2 is more distributed evenly under different humidity conditions. When the humidity rises from 20% RH to 100% RH, its conductivity gradually increases. The conductivity of PANI/MnO2 changes under various humidity conditions. The data points in the scatter plot matrix indicate that under high humidity conditions, its conductivity is higher. PEDOT’s conductivity performs well under different humidity conditions. When humidity rises from 20% RH to 100% RH, its conductivity gradually increases. PEDOT’s conductivity increases significantly under high humidity conditions, and the data point in the scatter plot matrix shows this change. AEC’s conductivity increases with the increase of humidity, but the change is not much. The data point in the scatter plot matrix shows the changing conductivity of AEC under different humidity conditions, indicating that its conductivity is limited at high humidity conditions.

The results show that high energy storage density materials such as graphene oxide (GO), polyaniline/manganese dioxide composites (PANI/MnO2) and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) have significant advantages in energy storage efficiency, Electrical response time and cycle stability are significantly better than traditional aluminum electrolytic capacitors (AEC). These experimental results have far-reaching implications for practical applications of energy storage systems and electronic devices.

First, the high energy storage efficiency and fast response capability of high energy storage density materials mean that electronic devices can store and release energy more efficiently, thereby achieving longer battery life and higher dynamic response speed. This is crucial for portable electronic devices such as smartphones and tablets, and can significantly improve the user experience. Secondly, the cycle stability of high energy storage density materials means that they can maintain stable performance during repeated charge and discharge processes, which is crucial for systems such as electric vehicles and energy storage power stations that require stable operation for a long time. Finally, the application of high energy storage density materials can also promote innovation in energy storage technology and electronic devices, provide strong support for the research and development of new electronic equipment, and further expand the application fields of electronic technology.

Conclusions

By studying the energy storage efficiency, electrical response time, cycling stability and environmental adaptability of high energy storage density materials, high energy storage density materials were better than traditional materials in many performance indicators. GO, PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT all showed good thermal stability at different temperatures. Under high humidity conditions, GO’s conductivity increased significantly, which showed that it performed well under rapid changing electrical conditions. Through comparison of electrical response time experiments, GO’s response time was the shortest, which showed that it performed well under the rapid change of electrical conditions. Under the influence of environmental humidity, the conductivity of the three high energy storage density materials increased with the increase of humidity, especially GO showed the most significant improvement. The results of electrical performance analysis showed that the impedance of GO increased from 1.82 OHM at 0.1 V to 12.50 OHM at 0.5 V, indicating that the impedance at a higher voltage increased significantly. PANI/MnO2 and PEDOT also showed similar trends, but the conductivity was very different under different voltage. Through the analysis of these data, this article can learn more about the performance advantages and potential of high energy storage density materials in various application scenarios. It shows huge application prospects and huge potential in terms of energy storage efficiency, electrical stability and response speed. Experiments have verified the excellent electrical performance of high energy storage density materials in the humidity change environment, which shows that they are very useful in practical applications. Of course, this study also has some shortcomings. The main reason is that although the circuit response of high energy storage density materials has been systematically experimentally verified and the performance has been compared, there is a lack of in-depth evaluation of the long-term stability and reliability of these materials in practical applications. Future research will focus on further optimizing the performance of high energy storage density materials, exploring their potential in more practical application scenarios, and in-depth research on the relationship between their microstructure and performance, providing a more comprehensive scientific basis for the development and application of high-performance energy storage materials.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhou, Y. et al. Two-birds-one-stone: Multifunctional supercapacitors beyond traditional energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 14(4), 1854–1896 (2021).

Mitali, J., Dhinakaran, S. & Mohamad, A. A. Energy storage systems: A review. Energy Storage Sav. 1(3), 166–216 (2022).

Majumder, P. & Gangopadhyay, R. Evolution of graphene oxide (GO)-based nanohybrid materials with diverse compositions: An overview. RSC Adv. 12(9), 5686–5719 (2022).

Vella Durai, S. C., Kumar, E., Muthuraj, D. & Bena Jothy, V. Investigations on structural, optical, and AC conductivity of polyaniline/manganese dioxide nanocomposites. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 10(4), 410–416 (2019).

Promsuwan, K. et al. Bio-PEDOT: modulating carboxyl moieties in poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for enzyme-coupled bioelectronic interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12(35), 39841–39849 (2020).

Wang, H., Guerrero, A. & Al-Mayouf, A. M. Kinetic and material properties of interfaces governing slow response and long timescale phenomena in perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 12(7), 2054–2079 (2019).

Cui, H. et al. Three-dimensional printing of piezoelectric materials with designed anisotropy and directional response. Nat. Mater. 18(3), 234–241 (2019).

Laschuk, N. O., Easton, E. B. & Zenkina, O. V. Reducing the resistance for the use of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis in materials chemistry. RSC Adv. 11(45), 27925–27936 (2021).

Liu, S., Shah, D. S. & Rebecca Kramer-Bottiglio Highly stretchable multilayer electronic circuits using biphasic gallium-indium. Nat. Mater. 20(6), 851–858 (2021).

Zhu, K. et al. The development of integrated circuits based on two-dimensional materials. Nat. Electron. 4(11), 775–785 (2021).

Choi, C. et al. Achieving high energy density and high power density with pseudocapacitive materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5(1), 5–19 (2020).

Zhou, C. Medium-and high‐temperature latent heat thermal energy storage: Material database, system review, and corrosivity assessment. Int. J. Energy Res. 43(2), 621–661 (2019).

Amiri, A. Recent progress of high-entropy materials for energy storage and conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 9(2), 782–823 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Electroceramics for high-energy density capacitors: current status and future perspectives. Chem. Rev. 121(10), 6124–6172 (2021).

Pan, Z., Hu, D., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Shen, B. & Zhai, J. Achieving high discharge energy density and efficiency with NBT-based ceramics for application in capacitors. J. Mater. Chem. C 7(14), 4072–4078 (2019).

Alkhouzaam, A., Qiblawey, H., Khraisheh, M., Atieh, M. & Al-Ghouti, M. Synthesis of graphene oxides particle of high oxidation degree using a modified hummers method. Ceram. Int. 46(15), 23997–24007 (2020).

Abbas, S. et al. One-pot synthesis of reduced graphene oxide-based PANI/MnO2 ternary nanostructure for high-efficiency supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 33(33), 25355–25370 (2022).

Ahmad, Z., Azman, A. W., Buys, Y. F. & Sarifuddin, N. Mechanisms for doped PEDOT: PSS electrical conductivity improvement. Mater. Adv. 2(22), 7118–7138 (2021).

Gopanna, A., Mandapati, R. N., Thomas, S. P., Rajan, K. & Chavali, M. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) of polypropylene (PP)/cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) blends for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Polym. Bull. 76(8), 4259–4274 (2019).

McCrae, K. et al. Assessing the limit of detection of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and immunoassay strips for fentanyl in a real‐world setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 39(1), 98–102 (2020).

Chaudhary, A. K. & Vijayakumar, R. P. Studies on biological degradation of polystyrene by pure fungal cultures. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22(5), 4495–4508 (2020).

Shahsavari, M., Jafari, M. & Grabinsky, M. Cemented paste backfill hydraulic conductivity evolution from 30 minutes to 1 week. Geotech. Test. J. 45(4), 753–777 (2022).

Li, H., Xiang, D., Han, X., Zhong, X. & Yang, X. High-accuracy capacitance monitoring of DC-link capacitor in VSI systems by LC resonance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34(12), 12200–12211 (2019).

Fu, Y., Xu, J., Shi, M. & Mei, X. A fast impedance calculation-based battery state-of-health estimation method. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69(7), 7019–7028 (2021).

Yu, X. & Li, J. Adaptive Kalman filtering for recursive both additive noise and multiplicative noise. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58(3), 1634–1649 (2021).

Fan, M. & Song, K. Reconfigurable low-pass filter with sharp roll-off and wide tuning range. IEEE Microwave Wirel. Compon. Lett. 30(7), 649–652 (2020).

Djeundje, V., Biatat & Crook, J. Dynamic survival models with varying coefficients for credit risks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 275(1), 319–333 (2019).

Chen, X., Wu, S., Shi, C. & Yanguo Huang. Sensing data supported traffic flow prediction via denoising schemes and ANN: A comparison. IEEE Sens. J. 20(23), 14317–14328 (2020).

Sharma, S. et al. SEM-Drude model for the accurate and efficient simulation of MgCl2–KCl mixtures in the condensed phase. J. Phys. Chem. A 124(38), 7832–7842 (2020).

Ji, Y., Li, G. & Shi-lin Qiu, and Simulation of second-order RC equivalent circuit model of lithium battery based on variable resistance and capacitance. J. Cent. South Univ. 27(9), 2606–2613 (2020).

AbdelAty, A. M., Yousri, D. A., Said, L. A. & Radwan, A. G. Identifying the parameters of cole impedance model using magnitude only and complex impedance measurements: A metaheuristic optimization approach. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 45(8), 6541–6558 (2020).

Saravanan, M. & Rajini, G. K. Comprehensive study on the development of an automatic helmet violator detection system (AHVDS) using advanced machine learning techniques. Comput. Electr. Eng. 118(8), 1–13 (2024).

Chakraborty, A. & Ray, S. Optimal allocation of distribution generation sources with sustainable energy management in radial distribution networks using metaheuristic algorithm. Comput. Electr. Eng. 116(4), 7–16 (2024).

Hasan, M. & Niyogi, R. Deep hierarchical reinforcement learning for collaborative object transportation by heterogeneous agents. Comput. Electr. Eng. 114(3), 109066 (2024).

Xu, B. Design of intrusion detection system for intelligent mobile network teaching. Comput. Electr. Eng. 112(12), 109013 (2023).

Funding

The work was funded by Key Project of Natural Science Research Projects in Anhui Province Universities (2024AH051760), Research Project on Science and Technology Innovation of Huangshan University College Students (XSKY202418) and Anhui Province College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Project (S202310375001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng Li is responsible for writing papers, organizing data, proofreading language, and designing research frameworks. Kang Fu is responsible for writing papers, analyzing data, improving research methods, comparing research content. Yuwan Cheng is responsible for liaising with research projects, implementing research projects, and organizing data. Kaijie Hong is responsible for analyzing data, improving research methods, comparing research content. Guo Zhang is responsible for writing papers and improving research methods.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Fu, K., Cheng, Y. et al. Circuit response and experimental verification of high energy storage density materials. Sci Rep 15, 5432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89300-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89300-w