Abstract

Hepatitis B virus genetic diversity (HBV) evaluation is scarcely done in Tanzania, imposing a crucial knowledge gap toward elimination of HBV infection by 2030. This cross-sectional study was conducted on purposively selected 21 plasma samples with high HBV-deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) levels of > 300,000IU/mL. DNA extraction was done using Qiagen DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Partial amplification of 423 bp of pol gene, sequencing and analysis; and statistical analysis by STATA version 15 were done. These patients had mean age of 41 ± 11 years with HBV-DNA median of 979 [185.5–8457.5] IU/mL. The genotypes detected were HBV/A; 76.2% (16/21), HBV/D; 19% (4/21), and lastly HBV/G; 4.8% (1/21). Most of the HBV/As and all of the HBV/Ds identified in this study did not cluster with HBV/As and HBV/Ds from other parts of the world. Overall, 19% (4/21) of the patients had HBV escape mutations (T123V, Y134N, P120T and T123A). In conclusion, HBV/A and HBV/D are predominant over time in North-western Tanzania. Most HBV/A and all HBV/D are unique to Tanzania as had been previously reported. However, the pattern of hepatitis B virus genetic diversity is changing in Northwestern Tanzania with occurrence of HBV/G as new genotype in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus is a prototype of hepatotropic circular and partially double-stranded DNA viruses known as the Hepadnaviridae family1,2. Human HBV belongs to Orthohepadnavirus and has many genotypes among the mammals involved2. The genome of HBV ranges from 3,182 bp (Genotype D)3,4 to 3,248 bp (Genotype G)5 which is organized into eleven genes, four highly overlapping structural genes or open reading frames (ORFs) which are polymerase (pol) ORF, Pre-Core/Core (PreC/C) ORF, Pre surface/surface (PreS/S) ORF, and Protein X (X)-ORF, and seven being regulatory sequences which are direct repeat 1 and 2 (DR1 and DR2 respectively), and enhancer region 1 and 2 (EN-I and EN-II respectively), Promoter I, Promoter II, and basic core protein (BCP)5,6. As a para-retrovirus, HBV replicates through a pregenomic RNA intermediate (pgRNA) generated from transcription of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) by host cell enzymatic machinery in the nuclear of the hepatocyte7. The reverse transcription is carried out by a viral encoded reverse transcriptase (RT), which lacks a 5’-3’ exonuclease for proofreading and is hence prone to mutations at the rate of 1.4–3.2 × 10− 5 base substitutions/site/year8. Other mechanisms involved are human migration and viral recombination in cases of HBV genotype or subgenotype co-infection9. HBV mutation can occur in any genomic region, producing variants having different clinical implications and severity10.

Currently, there are 10 known HBV genotypes (HBV/A-J), about 44 sub-genotypes, 9 serotypes, as well as several variants involving all four ORFs of HBV11. HBV genotypes/sub-genotypes and serotypes have all been shown to influence the transmission, pathogenesis, variant occurrences, and geographical distribution. In turn, variants influence the treatment, vaccine response, and HBV diagnostic failure12. Globally, the contribution of HBV genotypes is as follows: HBV/C (26.1%), HBV/D (22.1%), HBV/E (17.6%), HBV/A (16.9%), HBV/B (13.5%), and the other genotypes (HBV/F/G/H/I/J and recombinants) are < 2% each. There are differences in predominant HBV genotypes in different regions: America (America-HBV/H > HBV/G, ) Asia (HBV/C > HBV/D > HBV/B > HBV/A > HBV/Recombinants) Europe (HBV/D), Northern Africa (HBV/D > HBV/E), Middle Africa (HBV/A > HBV/E), Western Africa (HBV/E > > HBV/A), Southern Africa (HBV/A), and Eastern Africa (HBV/A > > HBV/D > > HBV/E)13. In Tanzania, genotypes reported from previous studies conducted among blood donors include A (86.9%), A1 (100%), and D (29%). Genotype HBV/E has also been reported14. With respect to HBV infection prevention and treatment, HBV surface and polymerase genes are important for frequent molecular evaluation. Both natural infection and vaccination target the HBsAg in the second hydrophilic loop (139 to 147 or 149 aa) by producing hepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs). This provides protection against all HBV genotypes and sub-genotypes and is responsible for the broad immunity afforded by HBV vaccination. However, mutations within this region of the HBV surface antigen have been reported15. Prevalence of these HBV escape mutations have been shown to increase over time16,17 and patient’s age18. Therefore, these HBV escape mutations can occur in a previously mutation-free WHO-HBV epidemiological region, and hence, frequent HBV escape mutation analysis in the respective region is necessary. On the other hand, several mutations involving the polymerase gene with reduced efficacy of anti-HBV antiviral drugs such as tenofovir (TDF) and entecavir (ETV) have been reported10. Polymerase mutations can be analyzed by either targeted partial or whole genome sequence analysis. In Tanzania, molecular characterization of HBV has been scarcely done on the HB-S gene in blood donors, reporting HBV/A, D, and E as well as negligible (0.4%) escape mutations in HBV/A and 0% of antiviral drug resistance-associated mutations. The HBV escape mutations reported were A128V, Q129H, and M133T in HBV/A and none in both HBV/D and HBV/E14. This scarcity of HBV molecular characterization studies makes Tanzania to lack key information required for elimination of HBV infection by 2030. Therefore, this study aims at routine molecular characterization of HBV virus by partial amplification of polymerase gene among chronically hepatitis B infected patients at Bugando Medical Centre, a tertiary referral hospital in Northwestern Tanzania.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The samples were from another study conducted from May 2023 to October 2023 which was approved by the joint Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences/Bugando Medical Centre (CUHAS/BMC) research ethics and review committee (CREC/663/2023). “The need for informed consent was waived by CUHAS/BMC research and review committee.“. Permission to use archived plasma specimens and to conduct the study at Bugando Medical Centre was from the previous study which was granted by the Bugando Medical Centre management (AB.286/317/01/PART “M”). All retrospective data were accessed with fully anonymity by using their hospital registration number from the Bugando Medical Records. After retrieving, the participants were given study identification number. These study identification numbers were used in all data analysis and communication related to the study. All data were treated with maximum confidentiality. All laboratory processes and experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study design, duration, area, population and sample size

This retrospective laboratory-based cross-sectional study had 21 purposively sampled from archived plasma specimens of chronically Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients attending at Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Northwestern Tanzania.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included plasma samples from repeatedly confirmed HBsAg-positive patients for more than six months. Included were all plasma samples of patients with HBV-deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) levels > 300,000 IU/mL and an available volume of > 300µL. All plasma remnants with volume < 300µL were excluded.

Data and plasma samples sorting

Demographic data and clinical data, including HBV-DNA, alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate amino transferase (AST), and full blood picture (FBP) parameters were collected by using a checklist from a medical record database. Plasma samples with > 300 uL and HBV-DNA level results of > 300,000 IU/mL were sorted and stored at -80 °C in the Bugando Medical Centre (BMC) Molecular laboratory until further analysis.

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequence analysis

A total of 200 µl of thawed plasma samples were drawn from each sample and used for DNA extraction using the Qiagen DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer instructions19. The extracted DNA in Eppendorf tubes was packed in tight double plastic bags and transported to Germany for amplification, sequencing, and sequence analysis as previously described20. HBV-DNA partial amplification and Sanger chain termination sequencing was done at a well specialize HBV virology institute, “Institute of Virology, Giessen, German”. The polymerase gene fragment amplified was about 423 bp. Genotyping using the HIV/HBV Stanford database21 and GenoPheno2hbv 2.022, NCBI HBV genotyping tool23 and hepatitis B database (HBVdb) tool24 was performed to determine HBV genotypes, subgenotypes and mutation pattern.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the A la Carte Mode, which is a package of Methodes et Algorthmes pour la Bio-Informatique (MABL)-Laboratoire d’Informatique, de Robotique et de Microélectronique de Montpellier (LIRMM), Université Montpellier, North-West of Montpellier, France. The procedure involved four steps. The first step was multiple alignment using MUSCLE, the second step was alignment curation using Gblocks, the third step was construction of the phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likehood (PhylML), and the fourth and last step was visualization of the tree using TreeDyn25. The bootstrap was set at 100.

Comparative phylogenetic analysis

A combined comparative phylogenetic analysis was performed. The local comparative phylogenetic analysis involved the current study HBV surface/partial polymerase sequences and previously obtained sequences from other previous studies done in Tanzania that were found in the NCBI nucleotide database26. The global comparative phylogenetic analysis involved sequences from the current study and those from other parts of the world, which were selected automatically by the HIV/HBV Stanford database21. The procedure involved preparation and uploading of the local comparative phylogenetic library into the HIV/HBV Stanford database, followed by construction of the comparative phylogenetic tree by using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL)27,28.

Preparation of the local comparative phylogenetic library

Local HBV/A comparative phylogenetic library

The library created contained 102 HBV/A sequences, of which 16 were from the current study and 86 sequences were from the previous study. HBV/A surface sequences from previous studies done in Tanzania were searched and downloaded from the NCBI nucleotide database. HBV/A surface sequences from previous studies found in the NCBI were 672, which were distributed as follows: North-western (Lake Zone) (TZLK) 304; Eastern Zone (TZE) 186; Southern Zone (TZS) 94; Southern Highlands Zone (TZSH) 32; Zanzibar (TZZN) 29; Northern Zone (TZN); 20; Western Zone (TZW) 6; and Unguja (TZUN) 126. The 86 sequences were obtained by using systematic cluster sampling, in which 30 sequences from the TZLK were obtained by sampling every 10th sequence, 10 sequences from the TZE were obtained by sampling every 18th sequence, 10 sequences from the TZS were obtained by sampling every 9th sequence, 10 sequences from the TZSH were obtained by sampling 3rd sequences, 9 sequences from the TZZN by sampling every 3rd sequence, 10 sequences from the TZN by sampling every 2nd sequences, all of the 6 sequences from the TZW, and 1 sequence from the TZUN.

Local HBV/D comparative phylogenetic library

The library created contained 99 HBV/D sequences in which 4 sequences were from the current study and 95 sequences were from the previous study. HBV/D surface sequences from previous study done in Tanzania were searched and downloaded from the NCBI nucleotide database. HBV/D surface sequences from previous study found in the NCBI were 95 and distributed as follows:- North-western (Lake Zone) (TZLK) 68; Eastern Zone (TZE) 22; Southern highlands Zone (TZSH) 2; Northern Zone (TZN) 2; and Western Zone (TZW) 126. All of the sequences from all of Zones were sampled.

Data management and analysis

Demographic, HBV-DNA levels, ALT, AST, and platelet parameters were extracted from medical records and then, along with serotype, genotype and mutation data, were entered and cleaned using Microsoft Excel 2016. APRI scores were calculated according to the respective formula29. HBV-DNA result values of target not detected (TND), < 20 IU/mL, and > 1.7 × 108 were treated as 0, 20, and 1.7 × 108 IU/mL, respectively. STATA software version 15 was used to analyze the data. Continuously skewed data were summarized using a medium and an interquartile range (IQR), while normally distributed data were summarized using the mean and standard deviation. Categorical data such as sex, genotypes, and mutations were summarized using proportion (per cent). We used two sample proportion tests to compare the significance of proportional differences of HBV escape mutation between current and previous studies. The p-value significance was set at < 0.05 and the confidence interval (CI) at 95%. The nucleic acid sequence datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GenBank repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/, with accession number from PQ446445-PQ446465.

Results

Patients’ social demographic and clinical data

Of the 22 purposively selected DNA samples with high HBV-DNA levels > 300,000 IU/mL, 21 were amplified and therefore sequenced. One sample (HBV_TZ 19) could not be amplified, possibly due to a mutation at the primer binding site. HBV chronically infected patients (21) had a mean age of 41 ± 11 years. Most of them, 85.7% (18/21) were male, and many, 38.1% (8/21) were from the Mwanza region. The median HBV-DNA levels were 979 [185.5–8457.5] IU/mL. Nevertheless, these patients had ALT levels with a median of 90.3 [55.9-185.7], with the majority, 81% (17/21) having levels above 41 U/L. They also had AST levels with a median of 168.0 [55.2–309.5], and most of them, 81% (17/21) had levels above 40 U/L. The APRI score was 2.7 [0.9–3.3] with more than half, 66.7% (14/21), of the patients having levels of more than 1 score (Table 1).

General molecular characteristics

The predominant genotype was HBV/A, 76.2% (16/21), followed by HBV/D, 19% (4/21) and the last was HBV/G, 4.8% (1/21). All HBV/A were sub-genotype A1. Serotypes in HBV/A1 were Adw2, 81.3% (13/16), followed by Ayw2, 12.4% (2/16), and the least was Adw1, 6.3% (1/16), while all HBV/D genotypes were Ayw2.

Hepatitis B escape mutations and the characteristics of the patients with versus without hepatitis B escape mutations

Out of 21 sequenced samples, 4 (19%) had HBV escape mutations. The escape mutations identified were T123V, Y134N, P120T, and T123A. These four patients with HBs-escape mutations had a median age of 48 [44-52.5] years, and all were male. None of the 21 patients studied had antiretroviral drug resistance associated mutation. Of these patients with HBV escape mutations, 2/4 (50.0%) were from Shinyanga, and the rest, 2/4 (50%), were from Geita and Mwanza, one patient from each region. All four patients had HBV DNA levels ranging from 553,996 IU/mL to 2,000,000 IU/mL. Among these four patients, two had an HBV/A genotype, and the other two had an HBV/D genotype. On the other hand, patients without HBV escape mutations were 81% (17/21) (Table 2). These patients had a median age [IQR] of 3131,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 years, and the majority of them, 77.8% (14/17), were male. The overall proportion of patients with HBV escape mutation was significant lower compared to those without escape mutation (19% versus 81%, p-value < 0.005%) in current study (Table 3). However, escape mutation showed to increase significantly among HBV/A (0.4% versus 12.5%, p-value < 0.005%) compared to previous findings in 2017. The HBV/D samples in this current study (4 samples) were too small to be compared with previous samples (95 samples) in 2017 (Table 4).

Phylogenetic analysis

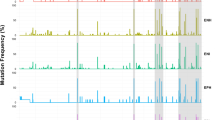

All 21 HBV sequenced are closely related according to their respective genotypes (Fig. 1).

Combined local and global comparative phylogenetic analysis for HBV/A

Combined local and global phylogenetic analysis showed that all of the HBV/A isolates obtained in this current study clustered randomly with previous isolates obtained from other regions of Tanzania. However, as it is for other previous isolates, most of the isolates of this current study did not mix-up with other isolates from outside Tanzania (Fig. 2).

Combined local and global comparative phylogenetic analysis for HBV/D and HBV/G

Combined local and global phylogenetic analysis showed that all of the HBV/D isolate obtained in this current study clustered with previous isolates obtained from Tanzania Northern and Lake Zones. Both of the current and the previous HBV/D isolates from Tanzania did not mix-up with other isolates from outside Tanzania (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic tree of the 21 hepatitis B virus isolates obtained in this current study. The phylogenetic tree was created by Methodes et Algorthmes pour la Bio-Informatique (MABL)-Laboratoire d’Informatique, de Robotique et de Microélectronique de Montpellier (LIRMM), Université Montpellier, North-West of Montpellier, France. The branch length is proportional to the number of substitutions per site25.

Combined local and global comparative phylogenetic tree of hepatitis B virus genotype A (HBV/A). Coloured and non-coloured isolates are HBV/A from within and outside Tanzania respectively. Sequences obtained from this current study are coloured blue. All non-blue coloured sequences are from previous study performed in Tanzania. The initials indicate different parts of Tanzania. TZLK: Tanzania Lake Zone, TZE: Tanzania Eastern Zone, TZSH: Tanzania Southern Highlands Zone, TZS: Tanzania Southern Zone, TZN: Tanzania Northern Zone, TZW: Tanzania Western Zone, TZZN: Tanzania Zanzibar, and TZU: Tanzania Unguja. The local comparative phylogenetic was created using HIV/HBV Stanford database21 and the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL)27,28.

Combined local and global comparative phylogenetic tree of hepatitis B virus genotype D and G (HBV/D and HBV/G). Coloured and non-coloured isolates are HBV/D and/or HBV/G from within and outside Tanzania respectively. Sequences obtained from this current study are coloured blue. All non-blue coloured sequences are from previous study performed in Tanzania. The initials indicate different parts of Tanzania. TZLK: Tanzania Lake Zone, TZE: Tanzania Eastern Zone, TZSH: Tanzania Southern Highlands Zone, TZS: Tanzania Southern Zone, TZN: Tanzania Northern Zone, TZW: Tanzania Western Zone, TZZN: Tanzania Zanzibar, and TZU: Tanzania Unguja. The local comparative phylogenetic was created using HIV/HBV Stanford database21 and the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL)27,28.

Discussion

In this study, we have determined the changing of HBV genetic diversity in Tanzania with the occurrence of new hepatitis genotypes. Among the 21 chronic hepatitis B-infected patients attending the Bugando Medical Centre, 16 (76.2%) had HBV/A (all being HBV/A1), 4 (19%) had HBV/D, and 1 (4.8%) had HBV/G. The identification and report of HBV/G is believed to be the first report in Tanzania, to the best of our knowledge. Additionally, 19% (4/21) of the patients had HBV escape mutations, which were distributed as follows: one patient had T123V and Y134N; two patients had P120T; and one patient had T123A. Although antiretroviral drug resistance-associated mutations were not observed, a significant increase in the proportion of HBV escape mutations among HBV/A and HBV/D with reference to previous study was observed, threatening the future efficacy of serological diagnostic techniques and the HBV vaccine in the country.

In this current study, three types of HBV genotypes were identified (HBV/A, HBV/D, and HBV/G), with the predominance of HBV/A and HBV/A1 as previously reported in Tanzania14. This observation shows that, HBV/A and HBV/A1 are predominant in Tanzania over time since 2017. This observation shows that HBV/A and HBV/A1 are predominant in Tanzania over time since 2017. Similarly, predominance of HBV/A1 has been reported elsewhere29,30. The second predominance of HBV/D observed in this current study was similar to what had been reported by a previous study in Tanzania14. In this index study, we also observed a predominance of serotype adw2 by 66.7% (14/21). The predominance of serotype Adw2 has been reported in Uganda31, Ethiopia32, and globally33.

We also identified HBV/G in our study for the first time. This patient (TZ_HBV 06) was genotyped HBV/A by using the HIV/HBV Stanford database21 and GenoPheno2hbv 2.022. However, TZ-HBV 06 was genotyped HBV/G based on the NCBI HBV genotyping tool23 and hepatitis B database (HBVdb) tool24. The phylogenetic genotyping tools such as HIV/HBV Stanford database and GenoPheno2hbv 2.0 genotyping tools uses phylogenetic analysis to genotype newly isolated strains by comparing them to the already known alignments and trees. These methods achieve this task by using multiple alignment approach of the whole submitted query sequence segment. The draw back from this approach is that, it cannot distinguish between inter-subtype recombinants and new subtypes. This is because both the newly isolated strains and the existing ones can branch out between clusters in a similar way34. The inconclusive hepatitis B genotyping due to viral genome variability can be overcomed by using new, non-phylogenetic typing tools such NCBI HBV genotyping tool35,36,37. Contrary to phylogenetic genotyping tools, the NCBI HBV Genotyping tool does not use multiple alignment of the whole submitted query sequence segment as input. Instead, the tool uses scored BLAST pairwise alignments between overlapping segments of a submitted query sequence and a reference sequence for each hepatitis B genotypes. This enables clear determination of the genotype of the query sequence, or of all genotypes involved and recombination breakpoints if the query is a recombinant34. Partial sequencing analysis using this segment (surface/polymerase segment) has been previously used to genotype HBV/G38. HBV/G is being reported for the first time in Tanzania, particularly in northern-western part.

Observation of HBV/G in Tanzania can be due to either of the two possibilities. First, although the geographic origin of HBV/G has been unclear since its discovery39, the possible Africa geographic origin has been proposed40 due to its similarity with HBV/E, which is endemic in Africa, particularly West Africa41. HBV/E has also been reported in other African countries, including the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Sudan, Uganda, Kenya30 and Tanzania14,30. Another possible explanation for the occurrence of HBV/G in Tanzania could be due to inter-continental interaction through human migration searching for new opportunities, such as mining activities. The patient with HBV/G in this study was diagnosed a few years after starting to work with North-Mara Barrick Mining in the Mara region. The diagnosis followed after the patient attended a nearby health facility complaining of generalized malaise, loss of appetite, and yellowish coloration of the eyes. The North-Mara Barrick Mining Company has workers originating from different parts of the world, including the America and Europe continents. This creates an inter-population social interaction with the potential for sexual behaviour interaction, resulting in the transmission of the American genotype (HBV/G) from America and Europe into Tanzania. If this circumstance is true, then the HBV/G will be regarded as a migration HBV genotype. Moreover, HBV/G could have been under identified in Tanzania. Usually the genotypes is invariably found in co-infection with other genotypes capable of furnishing HBeAg42,43 often existing as the minor variant among the viral quasispecies population and with fluctuating viral load44. Due to fluctuation of viral load, single time-point, cross-sectional low detection genotyping assay such as bulk sequencing may not be able to detect HBV/G during co-infection44. High detection limit genotyping assay such as deep sequencing, HBV/G-specific or highly sensitive universal primers amplification assays are the solution out39. In additional to less molecular studies which have been conducted, high limit detection genotyping assays have never been performed in Tanzania.

On comparative phylogenetic analysis, all of the HBV/A isolates obtained in this study clustered randomly with previous isolates obtained from other regions of Tanzania, showing high diversity. However, as it is for other previous isolates, most of the isolates of this study did not mix up with other isolates from outside Tanzania. These findings support Tanzania to be part of the geographic origin of HBV/A114, which further fortifies the hypothesis of the East African origin of HBV/A129,45,46. On the other hand, all of the HBV/D isolates obtained in this study clustered with previous isolates obtained from the Northern and Lake Zones of Tanzania and did not mix up with HBV/D isolates from outside the country. The fact that the HBV/D strains observed in this study did not mix up with other HBV/D strains from other East African countries, including Kenya47,48, Uganda31, Rwanda30 and Sudan49 suggests that the observed HBV/D subtype in this study might be new and originating solely from Tanzania. This observation was also reported by the previous study in Tanzania and suggested that the previous identified genotype could be the new HBV/D clade originating in Tanzania14. The HBV/G isolate obtained from this study clustered with HBV/A isolates in both comparative and non-comparative phylogenetic analyses. This could be due to the fact that the NCBI HBV genotyping tool23 and hepatitis B database (HBVdb) tool24 that were able to pick and differentiate the HBV/G from HBV/A could not perform phylogenetic analysis and therefore were not used for phylogenetic analysis. On the other hand, the phylogenetic analysis tools used were the Methodes et Algorthmes pour la Bio-Informatique LIRMM (MABL-LIRMM)25, and HIV/HBV Stanford database21, which uses phylogenetic genotyping approach. The Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) tool27,28, which was used for constructed phylogenetic tree and annotation, received a Nexus text tree file format which had been created by using the HIV/HBV Stanford database21 which had probably miss genotyped TZ_HBV 06 as genotype A instead of G.

In this index study, we found an HBV escape mutation of 12.5% (2/16) in HBV/A, 50% (2/4) in HBV/D, and 0% (0/1) in HBV/G, for an overall of 19% (4/21) in the whole study. Although the overall HBV escape mutation proportion increase in this study was non-significantly higher, a significant high proportion increase of escape mutation was observed in HBV/A (p-value < 0.005) and HBV/D (p-value < 0.005) compared to what had been reported previously in Tanzania in 201714. The difference could be due to the fact that the previous study population consisted of blood donors who were likely to be young and in their early stages of HBV infection, whereas the current study population is composed of chronic HBV-infected patients who are likely to have a long-standing duration of infection. The differences in study population can be further supported by several studies that have shown that HBV escape mutations can increase over time16,17 and with patients’ ages18. The proportion of HBV escape mutation (12.5%) in HBV/A was slightly lower than that of 14.9% (38/255) reported in the previous study conducted elsewhere in Europe50. Contrary to the previous study in Europe, which was composed of anti-HBV drug-experienced patients, all of the patients with HBV/A in this current study were not on anti-HBV drugs. Anti-HBV antiretroviral drugs have been shown to select and increase the occurrence of HBV escape mutations among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy51. The same previous study in Europe reported 25.3% (145/573) in HBV/D50, which was lower than that of 50% (2/4) reported by our current study. The difference could be attributed to differences in sample size. The sample size in the previous study in Europe for HBV/D was 573, while in the current study for HBV/D it was 4. However, both the previous study in Europe and the current study in Tanzania showed HBV/D to have a higher proportion (25.3% and 50%) of HBV escape mutations than HBV/A (14.8% and 12.5%) respectively. Although the current study has identified and reported new escape mutations (P120T, T123A, and Y134N) in Tanzania, these mutations have been identified by the previous study in Europe, which involved chronically infected patients similar to the current study50, contrary to the previous study in blood donors in Tanzania in 201714. However, contrary to the previous study in Europe, which involved chronically HBV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy50, most patients (75% = ¾) in the current study were not on antiretroviral treatment. This observation could be indicating that the HBV escape mutation observed in this current study is mostly not due to antiretroviral drug pressure selection. The possible explanations for the occurrence of these HBV escape mutations in this current study could be due to natural selection related to the inherent viral factors, immune selection pressure related to the infected patients, or environmental factors related to direct acquisition of an escape variant during the course of viral transmission. Based on inherent viral factors, HBV/D is believed to have a higher frequency of developing mutations, which are the pre-core A1896 mutation and the basal core promoter A1762T/G1764A mutation, than HBV/A52. This virological implication difference between HBV/D and HBV/A is not well documented in other types of mutations, such as escape mutations. Moreover, this concept cannot be implicated in our findings, as each of the HBV/A and HBV/D contributed equally among those patients with HBV escape mutations. Although the immunological selection pressure analysis needed more investigations, which were out of scope of this current study, the liver inflammatory markers signified by ALT were not significantly elevated and only taken at once, making immunological assessment difficult. Therefore, the environment factor related to direct acquisition of the escape variants stands in the lead to explain the possible source of the variants in this current study.

Limitation

This study was limited by lower sample size which might not give conclusive results. It was also a mono-centred study which might not give generalized results. Targeted sequencing performed in this study might not accurate subgenotype in some hepatitis B genotypes such as in genotype D in our study which requires whole genome analysis. The Nexus file format that was submitted into an iTOL for constructing the phylogenetic tree was created by HIV/HBV genotyping tool since it was not possible to create it by NCBI genotyping tool. As a result, TZ_HBV 06 which is genotype G clustered with HBV/A. This was a partial sequencing rather than a whole genome sequence analysis which might have revealed TZ_HBV 06 as a recombinant genotype of A and G instead of genotype G alone.

Conclusion

Our findings show that HBV/A (HBV/A1) and HBV/D are predominant over time in Northwestern Tanzania. Most HBV/A and all HBV/D are unique to Tanzania as had been previously reported. However, the pattern of hepatitis B virus genetic diversity is changing in Northwestern Tanzania with occurrence of HBV/G as new genotype in the region which might be requiring an attention. In addition to calling upon a bigger and more multicentred study so as to solidify the findings of this current study, we recommend frequent HBV molecular evaluation in the region.

Data availability

All the necessary data are included in the manuscript. Raw data are not publicly available. The non-nucleic acid sequence raw datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, MM (mathiasxnl2021@gmail.com). The nucleic acid sequence raw datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GenBank repository https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/, with accession number from PQ446445-PQ446465.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine amino transferase

- APRI:

-

Aspartate-Platelet Ratio Index

- AST:

-

Aspartate

- BCP:

-

Basal core promoter or Basal core promoter

- BLAST:

-

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- BMC:

-

Bugando Medical Centre

- cccDNA:

-

Covalently closed circular DNA

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- DR I:

-

Direct Repeat one

- DR II:

-

Direct Repeat two

- EN I:

-

Enhancer region one

- EN II:

-

Enhancer region one

- ETV:

-

Entecavir

- FBP:

-

Full blood Picture

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IU:

-

International unit

- MUSCLE:

-

Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NIMR:

-

National Institute of Medical Research

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- pgRNA:

-

Pre-genomic Ribonucleic Acid

- PhyML:

-

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree

- Pol:

-

Polymerase

- PreC/C:

-

Pre-Core/Core

- PreS/S:

-

Pre Surface/surface

- RT:

-

Reverse transcriptase

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TDF:

-

Tenofovir

- TND:

-

Target not detected

- TZ:

-

Tanzania

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Karayiannis, P. Hepatitis B virus: virology, molecular biology, life cycle and intrahepatic spread. Hep. Intl. 11, 500–508 (2017).

Glebe, D. & König, A. Molecular virology of hepatitis B virus and targets for antiviral intervention. Intervirology 57 (3–4), 134–140 (2014).

Tatematsu, K. et al. A genetic variant of hepatitis B virus divergent from known human and ape genotypes isolated from a Japanese patient and provisionally assigned to new genotype J. J. Virol. 83 (20), 10538–10547 (2009).

Okamoto, H. et al. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J. Gen. Virol. 69 (10), 2575–2583 (1988).

Huang, J. & Liang, T. J. A novel hepatitis B virus (HBV) genetic element with rev response element-like properties that is essential for expression of HBV gene products. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 (12), 7476–7486 (1993).

Chuang, Y-C., Tsai, K-N. & Ou, J-H-J. Pathogenicity and virulence of Hepatitis B virus. Virulence 13 (1), 258–296 (2022).

Beck, J. & Nassal, M. Hepatitis B virus replication. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 13 (1), 48 (2007).

Sugauchi, F. et al. A novel variant genotype C of hepatitis B virus identified in isolates from Australian aborigines: complete genome sequence and phylogenetic relatedness. J. Gen. Virol. 82 (4), 883–892 (2001).

Shen, T. & Yan, X-M. Hepatitis B virus genetic mutations and evolution in liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 20 (18), 5435 (2014).

Gao, S., Duan, Z-P. & Coffin, C. S. Clinical relevance of hepatitis B virus variants. World J. Hepatol. 7 (8), 1086 (2015).

Zhang, Z-H. et al. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 22 (1), 126 (2016).

Ma, Q. & Wang, Y. Comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus escape mutations in the major hydrophilic region of surface antigen. J. Med. Virol. 84 (2), 198–206 (2012).

Velkov, S., Ott, J. J., Protzer, U. & Michler, T. The global hepatitis B virus genotype distribution approximated from available genotyping data. Genes 9 (10), 495 (2018).

Forbi, J. C. et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Tanzania. J. Gen. Virol. 98 (5), 1048–1057 (2017).

Romanò, L. et al. Hepatitis B vaccination: are escape mutant viruses a matter of concern? Hum. Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 11 (1), 53–57 (2015).

Oon, C. J. & Chen, W. Current aspects of hepatitis B surface antigen mutants in Singapore. J. Viral Hepatitis. 5, 17–23 (1998).

Hsu, H. Y., Chang, M. H., Liaw, S. H., Ni, Y. H. & Chen, H. L. Changes of hepatitis B surface antigen variants in carrier children before and after universal vaccination in Taiwan. Hepatology 30 (5), 1312–1317 (1999).

Wakil, S. M. et al. Prevalence and profile of mutations associated with lamivudine therapy in Indian patients with chronic hepatitis B in the surface and polymerase genes of hepatitis B virus. J. Med. Virol. 68 (3), 311–318 (2002).

QIAGEN. QIAamp DNA mini and Blood Mini Handbook. (2023).

Seiz, P. L. et al. Studies of nosocomial outbreaks of hepatitis B in nursing homes in Germany suggest a major role of hepatitis B e antigen expression in disease severity and progression. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 305 (7), 663–672 (2015).

University, S. HIV Drug resistance database. 1998–2024.

informatik Mpi. Geno2pheno [hbv] 2.0. August, (2009).

(NCBI) NCfBI: Genotyping. Revised on 5 August 2024.

Lyon Ud. The Hepatitis B Virus database (HBVdb). 1988–2024.

Marseille Nice-genopole CNdlRSaRNdG. Methodes et Algorthmes pour la Bio-Informatique LIRMM (MABL-LIRMM). (2023).

(NCBI) NCfBI. Nucleotides with Accession number from KU595425 to KU594654. (2016).

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 5;52(W1):W78–W82 (2024).

(EMBL) EMBL. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL). (2024).

Kramvis, A. & Kew, M. C. Molecular characterization of subgenotype A1 (subgroup aa) of hepatitis B virus. Hepatol. Res. 37, S27–S32 (2007).

Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Xu, M., Li, X. & Zhang, Z. Distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes and subgenotypes: a meta-analysis. Medicine 100 (50), e27941 (2021).

Zirabamuzale, J. T. et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes a and D in Uganda. J. Virus Eradication. 2 (1), 19–21 (2016).

Ambachew, H., Zheng, M., Pappoe, F., Shen, J. & Xu, Y. Genotyping and sero-virological characterization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in blood donors, Southern Ethiopia. PloS One. 13 (2), e0193177 (2018).

Velkov, S., Protzer, U. & Michler, T. Global occurrence of clinically relevant hepatitis b virus variants as found by analysis of publicly available sequencing data. Viruses 12 (11), 1344 (2020).

Rozanov, M., Plikat, U., Chappey, C., Kochergin, A. & Tatusova, T. A web-based genotyping resource for viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (suppl_2), W654–W659 (2004).

Siepel, A. C., Halpern, A. L., Macken, C. & Korber, B. T. A computer program designed to screen rapidly for HIV type 1 intersubtype recombinant sequences. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 11 (11), 1413–1416 (1995).

Salminen, M. O., Carr, J. K., Burke, D. S. & McCUTCHAN, F. E. Identification of breakpoints in intergenotypic recombinants of HIV type 1 by bootscanning. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 11 (11), 1423–1425 (1995).

Lole, K. S. et al. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J. Virol. 73 (1), 152–160 (1999).

Dao, D. Y. et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype G: prevalence and impact in patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Med. Virol. 83 (9), 1551–1558 (2011).

Araujo, N. M. & Osiowy, C. Hepatitis B virus genotype G: the odd cousin of the family. Front. Microbiol. 13, 872766 (2022).

Lindh, M. HBV genotype G-an odd genotype of unknown origin. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 34 (4), 315–316 (2005).

Kramvis, A. & Kew, M. C. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Africa, its genotypes and clinical associations of genotypes. Hepatol. Res. 37, S9–S19 (2007).

Sugiyama, M. et al. Early dynamics of hepatitis B virus in chimeric mice carrying human hepatocytes monoinfected or coinfected with genotype G. Hepatology 45 (4), 929–937 (2007).

Sakamoto, T. et al. Mechanism of the dependence of hepatitis B virus genotype G on co-infection with other genotypes for viral replication. J. Viral Hepatitis. 20 (4), e27–e36 (2013).

Basic, M. et al. Not uncommon: HBV genotype G co-infections among healthy European HBV carriers with genotype A and E infection. Liver Int. 41 (6), 1278–1289 (2021).

Forbi, J. C. et al. Disparate distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes in four sub-saharan African countries. J. Clin. Virol. 58 (1), 59–66 (2013).

Hannoun, C., Söderström, A., Norkrans, G. & Lindh, M. Phylogeny of African complete genomes reveals a west African genotype a subtype of hepatitis B virus and relatedness between Somali and Asian A1 sequences. J. Gen. Virol. 86 (8), 2163–2167 (2005).

Mwangi, J. et al. Molecular genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus in Kenya. Intervirology 51 (6), 417–421 (2009).

Ochwoto, M. et al. Genotyping and molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus in liver disease patients in Kenya. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20, 103–110 (2013).

Yousif, M., Mudawi, H., Bakhiet, S., Glebe, D. & Kramvis, A. Molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus in liver disease patients and asymptomatic carriers of the virus in Sudan. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 1–11 (2013).

Colagrossi, L. et al. Immune-escape mutations and stop-codons in HBsAg develop in a large proportion of patients with chronic HBV infection exposed to anti-HBV drugs in Europe. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 1–12 (2018).

Perazzo, P. et al. virus (HBV) and s-escape mutants: From the beginning until now. (2015).

Lin, C-L. & Kao, J-H. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and variants. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 5 (5), a021436 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the partial funding support provided by Mwanza University for this work as part of the master thesis. The authors would also like to acknowledge Mr. Teonas A. Nyalu and Barnaba Sospeter from the department of medical records, Bugando Medical Centre for their support during data extraction. I would like to give warm thanks to Mr. Henerico Shimba for the tireless laboratory mentorship he gave to make this study possible. My generous thanks go to Prof. Mirambo and Prof. Stephen E Mshana for their tireless academic training, mentorship, search for sequencing assistance and support that without them, this work would have not been done.

Funding

In this fund for DNA extraction was provided by Mwanza University as part of the Master’s thesis. Sequencing support was provided by the University of Mainz and the Giessen institute of virology, both from German for sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM, MMM, and SEM designed the work. MM, IM, and SH performed the plasma sorting and DNA extraction. BG, PK, and GS performed the amplification PCR, and Sanger sequencing. MM, BG, PK, and GS performed the sequence analysis. MMM, SEM, HJ, HAN, BRK, ARS and SBK analyzed and interpreted the data. MM, AMM and SH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was critically reviewed by ARS, HAN, BRK, HJ, SBK, FK, BG, PK, GS, NEN, MMM, and SEM. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.Authors’ initialsMM: Mathias MlewaSH: Shimba HenericoHAN: Helmut (A) Nyawale.IM: Ivon Mangowi.ARS: Aminiel Robert Shangali.AMM: Anselmo Mathias Manisha. FK: Felix Kisanga.BRK: Benson R. Kidenya.HJ: Hyasinta Jaka.SBK: Semvua (B) Kilonzo.BG: Britta Groendahl. PK: Philipp Koliopoulos.GS: Gehring Stephan.NEN: Nyanda Elias NtinginyaMMM: Mariam M. Mirambo.SEM: Stephen E. Mshana.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mlewa, M., Henerico, S., Nyawale, H.A. et al. The pattern change of hepatitis B virus genetic diversity in Northwestern Tanzania. Sci Rep 15, 8021 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89303-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89303-7