Abstract

The PTAH oil field in Egypt’s northern Western Desert offers considerable potential for hydrocarbon production. This research centers on the Shiffah formation and evaluates its petrophysical properties using data from four wells. The analysis involves wireline logs (including gamma-ray, density, neutron, sonic, and resistivity), core samples, pressure readings, and cross-plots. A combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques was employed to assess the formation’s hydrocarbon-bearing capacity. The Shiffah formation primarily comprises sandstone, calcareous shale, and siltstone. Key petrophysical parameters such as shale volume, effective porosity, net thickness, and fluid saturations were mapped to evaluate variations across the field. Findings indicate that the reservoirs have an average shale content of 2.5%, an effective porosity of 11%, and an oil saturation averaging 47.84%. The net reservoir thickness ranges from 97.5 to 655 feet, with the net pay zones between 6.5 and 137 feet. These results underscore the potential for hydrocarbons within the field. Core analysis supports these findings, highlighting favorable horizontal and vertical permeability values. The correlation between well-log data and pressure information also aligns with production outcomes from Drill Stem Tests (DST). Among the wells, Ptah-1X exhibited the most promising petrophysical properties, whereas Ptah-4X was determined to be a dry well, with water saturation as high as 98%. Reservoir pressure analysis helped to pinpoint key fluid contacts, such as the oil–water contact (OWC). Pickett’s plot was used to calculate formation water resistivity, yielding values between 0.0170 and 0.0176 across the four wells. This comprehensive evaluation of the Shiffah formation offers valuable insights into its hydrocarbon potential and guides future exploration and drilling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

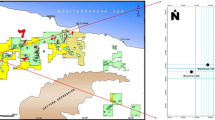

Egypt’s Western Desert has recently become a key area for oil production, with daily output reaching around 1.9 million barrels of oil equivalent (MM BOE/D)1. Most of these reserves are concentrated in the structural rift basins of the northern Western Desert (Fig. 1), which contain active petroleum systems in both syn-rift and post-rift sequences2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The map in Fig. 1 was created using (Petrel™ Schlumberger Modeling software, Version 2022.1)9 Additionally, there is potential in the pre-rift layers, where the Silurian and Devonian formations are considered potential source rocks, although their capacity to produce liquid hydrocarbons is debated6. The Paleozoic pre-rift sediments, particularly those identified in10, are viewed as promising reservoirs, though uncertainties exist regarding their distribution and characteristics. Recent exploration in the far northwestern desert has uncovered substantial yet underexploited reserves within these pre-rift strata6,11. More research is needed to understand the origins of these reserves and the factors controlling hydrocarbon accumulation in both pre-and syn-rift reservoirs.

The PTAH oil field is a significant site for this investigation, focusing on both the Lower Cretaceous syn-rift Alam El Bueib (AEB) and the Paleozoic pre-rift Shiffah sandstones. In contrast, nearby fields such as the Salam oilfield mainly target post-rift Bahariya and early syn-rift Khatatba sandstones4,7. This gives the PTAH field a unique role in understanding oil accumulation in both late syn-rift and pre-rift formations. This study uses various datasets, including well logs, core data, pressure readings, and production figures, to identify optimal drilling sites and mitigate future exploration risks. Furthermore, the study explores methodologies for petrophysical analysis, core evaluation, and interpreting pressure data.

The Matruh-Shushan Basin’s hydrocarbon potential assessment is influenced by its complex depositional and tectonic environment. This research examines four wells (PTAH-1X, PTAH-4X, PTAH-5X, and PTAH-9) located in this basin, a prominent feature of the North Western Desert (Fig. 1). The region’s considerable hydrocarbon potential has attracted attention from the oil and gas industry13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Its unique geology, with diverse sedimentary formations, structural elements, and key source and reservoir rocks25, makes it a prime area for hydrocarbon exploration and development.

This research emphasizes the critical role of petrophysical evaluation in determining hydrocarbon potential. Specifically, it examines the Shiffah formation using well logs, core samples, and other datasets to assess key reservoir properties like porosity, permeability, and fluid saturation. Although previous studies have explored other formations like the Khatatba and Alam El-Bueib in the Western Desert24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50, limited attention has been paid to the Shiffah formation in the Shushan Basin. This study aims to provide a detailed evaluation of the Shiffah reservoir in the PTAH field and estimate its potential hydrocarbon volumes.

Geologic setting

The Western Desert of Egypt, west of the Nile, spans over 700,000 square kilometers, covering nearly two-thirds of the country’s land area. The pre-Paleozoic basement is exposed in the southern part of the desert and slopes gently to the north. As this slope increases, so does the thickness of the overlying sedimentary layers, ranging from the Paleozoic to the present.

Mesozoic rift basins in the northern Western Desert, such as Shushan, Matruh, and Alamein, are crucial for oil production, holding over 40% of Egypt’s proven reserves. The Matruh-Shushan Basin has particularly thick sedimentary sequences in its northern part, due to faulting and slight compressional folding. This basin expanded during the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous and was inverted during the Late Cretaceous and Early Tertiary. The tectonic processes in this region have generated faults trending in various directions, especially during the Jurassic and Cretaceous.

The sedimentary sequence19,20,21,22,23 (Fig. 2) in this area extends from the Paleozoic to the present, with four main cycles of sedimentation: the Carboniferous, Late Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Miocene (Fig. 2). Marine transgressions mark some periods, while regression events dominated others, such as in the Triassic and Early Jurassic, with shorelines retreating northward. These events continued through the Early Cretaceous and Late Eocene.

The region’s sedimentary sequences include clastic facies from the Paleozoic and Lower Jurassic, carbonate formations from the Middle and Upper Jurassic, and a mixture of carbonates and clastics in the Cretaceous. One notable unit in this geological framework is the Shiffah formation, a pre-rift Paleozoic unit composed of dolomitic shale with interbedded porous sandstones and limestones (Fig. 2). The thickness of this formation varies between 708 and 140 feet in the Shushan Basin, and its proximity to source rocks makes it attractive for petroleum exploration.

Methodology

The petrophysical analysis of the Shiffah reservoirs was based on data from four wells: Ptah-1X, Ptah-4X, Ptah-5X, and Ptah-9 (see Fig. 1). This included well logs (Gamma-ray, Density, Neutron, PEF, Sonic, and Resistivity), core samples, and pressure data to evaluate the reservoirs and delineate pay zones. Reservoir lithology was determined using core descriptions, ditch cuttings, well-log interpretation, and cross-plots, allowing the calculation of key parameters such as shale volume, effective porosity, net pay thickness, and fluid saturations.

Side Wall Cores (SWC) were examined for porosity, permeability, and fluid saturation, particularly from Ptah-1X at depths ranging from 11,315 to 13,746 feet. These findings are illustrated in Fig. 3, showing the workflow for formation evaluation.

Further analysis of the petrophysical properties was conducted laterally and vertically across the study area. The shale volume was calculated using gamma-ray logs, while neutron and density logs were used to estimate total porosity (PHIT). Effective porosity (PHIE) was computed by correcting for shale. Water resistivity was determined through salinity data from drill stem tests and applied to Archie’s water saturation formula. The final analysis was presented through cross-plots, litho-saturation models, and contour maps to identify fluid types and reservoir characteristics (Table 1).

The Archie equation was chosen to calculate water saturation (Sw) because the reservoir has relatively low shale content (approximately 21%), making it suitable for this model.

Additionally, the parameters required for the Archie equation, such as porosity and formation water resistivity, were readily available and well-matched to the dataset. While the Indonesian equation is more effective for shaly formations, its complexity was unnecessary for this study, as the Archie equation provided accurate results validated against core and production data.

Results

Lithologic analysis using cross plots

The cross-plot analysis highlights that the Shiffah formation in the wells consists mainly of sandstone, calcareous shale, dolomitic shale, mudstone, and siltstone, with a notable presence of calcareous content. The majority of the data points, represented in yellow and orange, are clustered in the upper-left quadrant of the plots, indicative of a hydrocarbon-rich zone (see Fig. 4). The analysis reveals that the main lithologies are calcareous shale, sandstone, and siltstone, with data from the Shiffah Reservoirs closely following the sandstone trend. Some points near the limestone and dolomite lines suggest the presence of calcareous materials. Additionally, oil presence is indicated by the upward shift of certain data points. The M–N cross-plots in Fig. 5 further support the density-neutron cross-plots, illustrating the lithologic makeup. These plots show the dominance of sandstone lithology, with dots suggesting quartz presence and calcareous minerals surrounding calcite, as well as calcareous materials mixed with shale. Displaced points in the upper right signify oil saturation, while sandstone is represented by points along the sandstone line in the quartz matrix. Overall, the Shiffah formation shows a transition from sandstone to a mix of calcareous rock, shale, and siltstone. The identification of hydrocarbon-bearing sandstone within the Shiffah formations has been accurately validated using these newly integrated cross-plots (see Figs. 6 and 7). These findings align well with lithological descriptions from core samples and mud logs, ensuring consistency throughout the analysis.

Are the (RHOB-NPHI) cross plots of the Shiffah formation of Ptah-1X (A), Ptah-4X (B), Ptah-5X (C), and Ptah- 9 (D) wells and 55 API in the four wells, particularly in the lower right section of the plot. The density of the lower ends varied from 2.35 to 2.55 g per cubic centimeter. A substantial part of the storyline depicted shale parts of the Ptah-1X well, which were colored purple. These sections were observed to migrate in a northwestern direction, accompanied by a growing prevalence of non-sand materials and a spike in gamma-ray readings ranging from 65 to 130 API. The prevalence of sand was noted in all four wells, and it exhibited an upward trend as the depth decreased.

The terms M and N are defined as follows:

where the formation fluid transit time (∆tf) and the sonic log transit time (∆tlog) are both expressed in microseconds per foot (µs/ft). Similarly, the bulk density from the density log (ρb) and the formation fluid density (ρf) are measured in grams per cubic centimeter (g/cc). Additionally, the fluid’s neutron porosity (∅NF) and the neutron porosity from the neutron log (∅N) are quantified in decimal form.

Litho saturation model for the studied wells

Litho saturation model for PTAH-1X well

Utilizing cutoffs of 40% for shale volume (Vsh), 6% for porosity (Ø), and 60% for water saturation (Sw), the Shiffah formation in PTAH-1X is determined to have a net pay zone of approximately 137 ft. This zone has an average shale volume of 4%, effective porosity between 11 and 15%, and an average water saturation of 16%. This well is the most productive of those studied. The litho-saturation model for PTAH-1X is shown in Fig. 8.

Litho saturation model for PTAH-4X well

In the Shiffah formation of PTAH-4X, thick sandstone layers are present, but the well does not contain any productive zones, yielding no net pay. A fully saturated water reservoir is detected between 12,495 and 12,955 ft. Based on shale volume, porosity, and water saturation cutoffs, the formation is found to be non-commercial. The shale volume averages 3%, porosity is around 10%, and water saturation is about 98%, as shown in Fig. 9.

Litho saturation model for PTAH-5X well

The log interpretation of PTAH-5X, as shown in Fig. 10, identifies thick sandstone layers between depths of 12,274 and 12,413.5 ft. A Drill Stem Test (DST) conducted from 12,366 to 12,396 ft confirmed the presence of water with a resistivity of 0.017 Ω-m at 250°F. Using production and core analysis parameters (m = 2, n = 2, a = 1) alongside shale volume, porosity, and water saturation cutoffs, a net pay zone of around 95 ft is estimated. The shale volume averages 5%, porosity is approximately 10%, and water saturation is around 25%. RFT pressure was invalid due to adverse hole conditions.

Litho saturation model for PTAH-9 well

For PTAH-9, the litho-saturation model (Fig. 11) indicates dense sandstone within the Shiffah formation, with a thickness of 235 ft. This zone has a net pay of around 6.5 ft, with an average shale volume of 2%, effective porosity between 7 and 8%, and an average water saturation of 53%. Total gas is expressed as a methane equivalent percentage, accounting for hydrocarbons detected from the drilling mud system.

Picket plot and formation water resistivity (Rw)

The Picket plot for the Shiffah Zones (Figs. 12 and 13) shows data points ranging from 25 to 100% water saturation (Sw), with some points above the 25% Sw line, suggesting an oil-producing zone. This confirms the calculated water saturation values, with clusters between 25 and 100% Sw indicating oil-bearing zones, except in PTAH-4X, which shows no oil pay. The consistent distribution of data supports the conclusion that the reservoirs are predominantly oil-bearing. The resistivity log for formation water resistivity (Rw) offers insights into the sedimentary deposits’ electrical properties, indicating brines in the pore spaces. The formation water resistivity values in the four wells are estimated using the Pickett plot method, with Shiffah-1X, Shiffah-4X, Shiffah-5X, and Shiffah-9 displaying Rw values of 0.0176, 0.0170, 0.0175, and 0.0172, respectively.

Core data analysis

Routine core analysis on 54 sidewall core (SWC) plugs from the AEB and Shiffah formations in PTAH-1X revealed porosity, permeability, and grain density measurements. The plugs were cleaned with organic solvents and dried at 60 °C for 2 days before testing with a helium expansion gas porosimeter. A total of 44 samples were analyzed, with permeability ranging from 0.02 to 839 mD, and porosity from 2.4 to 24.5%. The core data showed that reservoir quality improves with depth, particularly between 12,944 and 13,746 ft, where good-quality macro pores were found.

The core analysis results confirm that the horizontal permeability values are significantly better than the vertical permeability values. This is evident from the routine core measurements in PTAH-1X, where permeability ranged from 0.02 to 839 mD, with improved reservoir quality observed in deeper formation sections. The favorable horizontal permeability indicates better fluid flow potential along the bedding planes, which is consistent with the sandstone-dominated lithology identified through cross-plots and core data. These findings align with the observed macro pore structures and reinforce the reservoir’s suitability for hydrocarbon production. Figure 14 shows a Comparison of core permeability and log-derived permeability showing strong matching in the SHIFFAH sand reservoir in the PTAH-1X Well.

Comparison of core permeability (violet circles) and log-derived permeability; the used equation is (Log10(predicted permeability), gold curve) = 0.64*log10(Horizontal core permeability) + 0.6932, core porosity (red circles) and logs derived porosity (blue curve) showing strong matching in SHIFFAH sand reservoir in PTAH-1X Well.

Area interpretation maps

The analyses summarize the characteristics of the Shiffah reservoirs and pay zones (Figs. 13 and 14), including four wells across the oil field. Each area is evaluated based on hydrocarbon potential, considering shale volume, porosity, and water and hydrocarbon saturation levels (Figs. 15 and 16).

Formation fluid type and fluid contacts

The analysis of formation pressure within the wells is crucial for understanding fluid characteristics, fluid contact points, and overall reservoir conditions. These findings play a vital role in both reservoir evaluation and management. In the PTAH-1X well, the oil–water contact (OWC) was identified at 11,765 ft TVDSS, as depicted in Fig. 17A. The pressure gradient reveals fluid oil characteristics alongside a low-salinity formation water gradient. This OWC aligns with open-hole log interpretations30,54,55,56,57,58,59, further corroborated by DST production results. In contrast, the PTAH-4X well (Fig. 17B) shows an OWC at 10,690 ft TVDSS within the AEB Formation, with no such contact observed in the Shiffah formation, as all reservoirs there are positioned above the main contact. Pressure gradients indicate oil presence, validated by production data, with the OWC’s approximate location inferred from open-hole logs. In the PTAH-9 well (Fig. 17C), the oil-bearing section revealed no discernible OWC. The pressure gradient suggests the fluid type in the AEB Formation is oil, while pressure readings in the Shiffah formation were below the fluid contact, specifically within the water leg zone. Poor hole conditions compromised the RFT pressure readings in the PTAH-5X well. Reservoir pressure and temperature were recorded at approximately 5300 psi and 285°F, respectively. The PTAH-1X well exhibits a pressure of 5400 psi, with a gradient of 0.28 psi/ft and a mobility of around 108 md/cP. Meanwhile, in the PTAH-4X well (Fig. 17B), oil presence is confirmed in the AEB, while water exists below the OWC in the Shiffah formation, particularly in the water leg and transitional zones. By integrating pressure data with Litho-Saturation models, Drill Stem Test (DST) or Perforation Test results, and additional datasets, it is possible to accurately delineate fluid types and boundaries within the PTAH wells. Moreover, pressure analysis aids in understanding reservoir depletion trends and water saturation changes over time. Such comprehensive pressure assessments are instrumental for optimizing reservoir management and maximizing hydrocarbon recovery from the studied wells.

The analysis of the Shiffah formation across four wells demonstrates significant insights into reservoir characteristics, particularly the thickness and fluid distribution. The Shiffah formation’s net sand thickness is 655 ft in PTAH-1X and 413.5 ft in PTAH-4X, making it the thickest among the studied wells. This formation contains distinct oil and water zones, aiding in the delineation of the oil–water contact (OWC). PTAH-1X exhibits high resistivity and gas readings, indicating a productive oil reservoir, whereas PTAH-4X shows lower resistivity and a minor neutron-density crossover, typical of water-saturated zones. Key petrophysical parameters such as Bulk Volume Hydrocarbons (BVH), Bulk Volume Water (BVW), shale volume (Vsh), and effective porosity (Øeff) were evaluated using litho-saturation models, providing a detailed lithological and saturation profile. The Shiffah formation is favorable for petrophysical analysis, especially in the thicker sandstone sections in the northeastern (PTAH-5X) and southwestern (PTAH-1X) parts, as it shows high effective porosity, low shale content, and high oil saturation. Among the wells, PTAH-9, located on the northern slopes of the Shushan Basin, shows the lowest oil saturation (47%), while PTAH-1X and PTAH-4X are positioned on the northwestern sides of the basin. Pressure analysis revealed that PTAH-1X is the only well to penetrate both oil and water columns in Shiffah, while PTAH-9’s pressure data is limited to the transition zone and water leg, with no penetration into the oil column (Fig. 18). The pressure values in the AEB Formation for PTAH-1X and PTAH-9 are 4539 psi and 4500 psi, respectively, suggesting minimal depletion. Similarly, the Shiffah pressure data indicates 5428 psi in PTAH-1X and 5350 psi in PTAH-9, with overall low depletion observed across all wells. Notably, the pressure decline in PTAH-4X between April 2015 and November 2015 was modest, reflecting limited reservoir depletion in the region. The distinct OWCs identified in PTAH-1X and PTAH-9 within the AEB-3E reservoir suggest potential oil presence at depths above 10,690 ft TVDSS. Overall, the minimal pressure reduction across the wells suggests limited connectivity, likely due to structural or stratigraphic variations within the reservoir (Figs. 18 and 19).

Integrated structural mapping and seismic interpretation

The structural depth maps for the AEB-3E and Pre-rift Paleozoic Shiffah formations (Figs. 20 and 21), derived from data across the four studied wells, provide critical insights into hydrocarbon distribution within the reservoirs. These maps delineate the oil–water contacts (OWC), represented by a blue line, which were interpreted from well logs and validated through pressure cross-plots. The strong correlation between these methods ensures the accuracy and reliability of the identified fluid interfaces, offering a robust visualization of the reservoir architecture.

On the left side presents a depth structure map of the AEB-3E reservoir within the four studied wells. The oil–water contact (OWC—the blue line) is identified approximately at 11,428 ft (approximately between − 10,680 to − 10,690 ft subsea) based on well-log interpretation. The right side presents a depth structure map of the Pre-rift Paleozoic formation within the four studied wells. The oil–water contact (OWC—the blue line) is identified at 12,503 ft (approximately between – 11,700 ft to − 11,765 ft subsea) based on well-log interpretation. The alignment of seismic data with structural maps strengthens the interpretation, ensuring that the subsurface framework is depicted with high precision. A major normal fault located adjacent to the wells is also considered in the interpretation, influencing fluid distribution and reservoir continuity. By integrating the seismic data with structural maps, the study provides a robust model of the subsurface, accounting for faulting effects and offering a clearer picture of the reservoir’s geometry and hydrocarbon potential. This comprehensive approach is essential for reducing exploration risks, optimizing reservoir management, and ensuring more accurate resource estimates.

On the left side is (N-S Seismic line:11,622), and on the right side is (E-W Seismic line: 6557), see structure maps (Fig. 20); to enhance the interpretation, two seismic lines were integrated with the structural maps, providing a comprehensive visualization of the subsurface geometry and stratigraphic features. This integration confirms the continuity of key horizons, validates structural closures and ensures precise delineation of fault systems and reservoir boundaries. The alignment of seismic data with structural maps further reinforces the accuracy of the subsurface framework interpretation.

The combination of these approaches underscores the robustness of the integrated methodology used in this study, offering a detailed understanding of the reservoir’s geometry, fluid distribution, and hydrocarbon potential. This comprehensive interpretation is pivotal for reducing exploration risks and optimizing reservoir management strategies.

Discussion

The findings of this research align with and expand upon previous studies in similar geological settings. A recent study conducted on the Baltim Eastern and Northern gas fields in the offshore Nile Delta (Scientific Reports, November 2023)60 evaluated the petrophysical properties of the Abu Madi and Qawasim Formations. This study identified significant gas condensate accumulations, with low shale content (~ 21%), high effective porosity (18% in the BN1 well), and gas saturation values averaging 58–60%. Similarly, the current study on the Shiffah formation in the PTAH oil field highlights favorable petrophysical characteristics, including low shale content (2.5%), moderate effective porosity (11%), and oil saturation averaging 47.84%.

Both studies underscore the importance of integrating various datasets, such as wireline logs, core analysis, and pressure data, for accurate reservoir characterization. However, key differences exist between the two formations. The Abu Madi Formation exhibits higher porosity and gas saturation values, suggesting its suitability for gas condensate production, while the Shiffah formation demonstrates moderate porosity and oil saturation, highlighting its oil production potential. Additionally, the net reservoir thickness varies significantly, with the Abu Madi Formation ranging from 25.5 to 131.5 m and the Shiffah formation exhibiting a broader range of 97.5–655 feet.

The challenges addressed in these studies also differ. The Abu Madi Formation research emphasizes reducing drilling risks and optimizing exploration locations, identifying the southern and central portions of the Abu Madi Paleo Valley as highly favorable zones. Conversely, the Shiffah formation analysis focuses on identifying fluid contacts and minimizing the occurrence of dry wells, such as Ptah-4X, which exhibited 98% water saturation.

These distinctions emphasize the diverse geological and petrophysical characteristics of Egypt’s reservoirs, necessitating tailored approaches for their evaluation and development. The insights gained from the current research further contribute to a comprehensive understanding of hydrocarbon potential in Egypt’s Northern Western Desert, while also offering valuable comparisons for future studies in other regions.

While this study has provided valuable insights into the Shiffah formation, several areas for future research can enhance our understanding and improve exploration and production efforts. Future work should focus on advanced reservoir modeling techniques, such as 3D seismic modeling, to better capture the formation’s heterogeneity and refine well placement. A more detailed study of shale-sandstone transitions could further improve predictions of fluid flow and hydrocarbon saturation in areas with complex lithologies.

Conclusion

The analysis of the Shiffah formation indicates significant potential for hydrocarbon reserves in the studied wells (see Fig. 19 Histograms summarize the results of SHIFFAH-B for all Wells).

-

Cross-plot analyses confirm the lithological composition of the formation.

-

Litho-saturation models reveal variable net pay thicknesses across different wells, identifying both productive and non-productive zones.

Integration of core This study evaluates the hydrocarbon potential of the Shiffah formation through detailed petrophysical analysis, incorporating well log data, core samples, and pressure data from the wells PTAH-1X, PTAH-4X, PTAH-5X, and PTAH-9. Key findings from the study are summarized as follows:

-

The Shiffah formation demonstrates significant hydrocarbon potential, with productive zones identified in certain wells, such as PTAH-1X, while others, like PTAH-4X, show non-productive zones. This variability highlights the need for targeted exploration strategies across the field.

-

Cross-plot analyses confirm that the Shiffah formation consists primarily of sandstone, calcareous shale, and siltstone, with hydrocarbon-rich zones predominantly made up of sandstone. This lithological understanding is crucial for determining fluid types and optimizing well placement.

-

Litho-saturation models reveal varying net pay thicknesses, with PTAH-1X showing the most productive zone at 137 ft of net pay. PTAH-5X also demonstrates a moderate net pay zone of approximately 95 ft, while PTAH-4X lacks productive zones due to high water saturation, confirming the importance of detailed saturation models.

-

Core data analysis indicates that horizontal permeability is significantly higher than vertical permeability in the Shiffah formation. This observation is consistent with the presence of macro-pores in the deeper sections of the formation, where fluid flow potential along bedding planes is enhanced. The improved horizontal permeability suggests better reservoir quality for hydrocarbon production.

-

The use of the Archie equation to calculate water saturation (Sw) proved effective due to the low shale content of the formation. This approach was validated by core and production data, confirming the existence of oil-saturated zones in the Shiffah reservoirs. The Picket plot analysis further validated these findings, reinforcing the presence of oil-bearing zones in most wells, except for PTAH-4X, which showed no oil pay.

-

The integration of core data, well logs, and formation pressure data enhances the overall understanding of the reservoir’s characteristics, including fluid saturations, porosity, and permeability. This comprehensive analysis is critical for making informed decisions regarding future exploration and development.

-

Improved porosity with depth in the pre-rift Paleozoic formations could be attributed to diagenetic processes such as dissolution, which enhance pore space in deeper intervals7. This phenomenon might occur due to the presence of reactive mineral phases (e.g., feldspars or carbonates) that undergo dissolution under increased pressure and temperature conditions, forming secondary porosity. Additionally, variations in the original depositional environment or facies changes with depth might also contribute to differences in porosity. For instance, deeper sections may correspond to more porous and permeable reservoir facies, such as sandstones, deposited in high-energy environments. These factors collectively could explain the observed porosity trend. Three distinct reservoir rock types (RRTs) were identified in the Shiffah and AEB reservoirs. According to7, the highest quality reservoir rocks, RRTI, are found exclusively in the Shiffah sandstones, whereas the AEB reservoir is primarily composed of RRTII and RRTIII. RRTI consists of quartz-rich sandstones with an open, uniform pore structure system. In contrast, RRTII and RRTIII feature a denser pore system with significant amounts of pore-filling cement. These results and analysis highlight the existence of excellent reservoir rock types in the pre-rift succession connected with the Jurassic kitchen which charged the entire syn- and post-rift reservoirs, Moreover, a better-connected pore system and a more open pore network is observed in the Shiffah sandstones7.

-

These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing resource extraction in the Shiffah formation. The results support the potential for continued exploration, especially in areas with higher horizontal permeability and oil saturation, like PTAH-1X. Future drilling and development should prioritize these productive zones to maximize hydrocarbon recovery.

In conclusion, this study offers a detailed and reliable framework for assessing the Shiffah formation’s hydrocarbon potential, highlighting areas for further exploration and improving our understanding of reservoir properties. The integration of petrophysical data, core analysis, and advanced modeling techniques provides a solid foundation for optimizing future resource extraction efforts.

Data availability

Data can be requested from Dr. Ahmed Ismail Mahmoud the first author of this article (email: aismail@sci.cu.edu.eg; isamil427@gmail.com).

References

Hassan, M., Leila, M., Ahmed, M., Issa, G. & Hegab, O. Geochemical characteristics of natural gases and source rocks in Obayied sub-basin, north Western Desert, Egypt: Implications for gas-source correlation. Acta Geochim. 42(2), 241–255 (2023).

Alsharhan, A. S. & Abd El-Gawad, E. A. Geochemical characterization of potential Jurassic/Cretaceous source rocks in the Shushan Basin, northern Western Desert Egypt. J. Pet. Geol. 31(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-5457.2008.00416.x (2008).

Abdelwahhab, M. A., Radwan, A. A., Mahmoud, H. & Mansour, A. Geophysical 3D-static reservoir and basin modeling of a Jurassic estuarine system (JG-Oilfield, Abu Gharadig basin, Egypt). J. Asian Earth Sci. 225, 105067 (2022).

Leila, M., Loiseau, K. & Moretti, I. Controls on generation and accumulation of blended gases (CH4/H2/He) in the Neoproterozoic Amadeus Basin Australia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 140, 105643 (2022).

Leila, M., Yasser, A., El Bastawesy, M. & El Mahmoudi, A. Seismic stratigraphy, sedimentary facies analysis and reservoir characteristics of the Middle Jurassic syn-rift sediments in Salam Oil Field, north Western Desert Egypt. Mar. Pet. Geol. 136, 105466 (2022).

El Matboly, E. A., Leila, M., Peters, K. E. & El Diasty, W. S. Oil biomarker signature and hydrocarbon prospectivity of Paleozoic versus Mesozoic source rocks in the Faghur-Sallum basins, Egypt’s Western Desert. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 217, 110872 (2022).

Mahmoud, A. I., Metwally, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Leila, M. Controls on hydrocarbon accumulation in the pre-rift paleozoic and late syn-rift cretaceous sandstones in PTAH oil field, north Western Desert, Egypt: Insights from seismic stratigraphy, petrophysical rock-typing, and organic geochemistry. Mar. Pet. Geol. 155, 106398 (2023).

Lasheen, I., Noureldin, A. M. & Metwally, A. Reservoir characterization of the Abu Roash D Member through petrography and seismic interpretations in Southern Abu Gharadig Basin, Northern Western Desert Egypt. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8966 (2024).

Petrel (2022), https://www.slb.com/products-and-services/delivering-digital-at-scale/software/petrel-subsurface-software

Abuzaied, M., Metwally, A., Mabrouk, W., Khalil, M. & Bakr, A. Seismic interpretation for the Jurassic/Paleozoic reservoirs of QASR gas field, Shushan-Matrouh basin north Western Desert Egypt. Egypt. J. Pet. 28(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2018.12.008 (2019).

Makled, W. A., Mostafa, T. F., Mousa, D. A. & Abdou, A. A. Source rock evaluation and sequence stratigraphic model based on the palynofacies and geochemical analysis of the subsurface Devonian rocks in the Western Desert Egypt. Mar. Pet. Geol. 89, 560–584 (2018).

Bayoumi, T. The influence of the interaction of depositional environment and synsedimentary tectonics on developing some Late Cretaceous source rocks, Abu Gharadig Basin, Western Desert, Egypt. In Proceedings of the EGPC 13th Petroleum Exploration & Production Conference, Cairo Vol. 2, pp. 475–496 (1996).

Noureldin, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. M. Superimposed structure in the southern periphery of Abu Gharadig Basin, Egypt: Implication to petroleum system. Contrib. Geophys. Geodesy 53(2), 97–110 (2023).

Noureldin, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M., Chikiban, B. & Metwally, A. Formation evaluation utilizing a new petrophysical automation tool and subsurface mapping of the Upper Cretaceous carbonate reservoirs, the southern periphery of the Abu-Gharadig basin, Western Desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 205, 104977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2023.104977 (2023).

Noureldin, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. Structural and petroleum system analysis using seismic data interpretation techniques to upper cretaceous rock units: A case study, West Abu-Sennan Oil Field, Northern Western Desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 198, 104772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2022.104772 (2023).

Noureldin, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. Delineating tidal channel feature using integrated post-stack seismic inversion and spectral decomposition applications of the Upper Cretaceous reservoir Abu Roash C: A case study from Abu-Sennan oil field, Western Desert Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 205, 104974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2023.104974 (2023).

Selim, E. S. I., Omran, M. A. & El-Twargy, E. Evaluation of hydrocarbon prospects by the use of 3D seismic data at the Cretaceous formations in Jade field, Matruh Basin, North Western Desert Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1–17 (2021).

El-Nikhely, A. et al. Decoding of seismic data for complex stratigraphic traps revealing by seismic attributes analogy in Yidma/Alamein concession area Western Desert Egypt. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 12(12), 3325–3338 (2022).

Noureldin, A. M. et al. Hydrocarbon potential in the northern Egyptian Red Sea: Insights from geophysical datasets and onshore analogues. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79605-7 (2025).

Noureldin, A. M., Saleh, G., Moussa, A., Hossam, O., Busanello, G., Elmidany, A., Shabana, M., Yousef, M. & Elhabashy, H. (2024). Exploring deepwater pre-salt plays by reimaging the offshore Nile Delta Basin, Egypt. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition https://doi.org/10.2118/223223-MS

Saleh, G. et al. Rejuvenating exploration opportunities in Egypt’s Mediterranean region. Leading Edge 43(9), 588–593. https://doi.org/10.1190/tle43090588.1 (2024).

Saleh, G., Diab, H., Helal, M., Ouda, M., Yassein, R., Ahmed, M., Saleh, T., Noureldin, A. & Radwan, M. (2023). Delineating exploration potential in shelf and deep-water areas in the offshore East Nile Delta. In EGM Conference Proceedings https://doi.org/10.3997/2214-4609.202330034

Noureldin, A. M., Osman, O. A., Hanafy, A. G., Nour, A. M., Benyamin, M. H., Mostafa, R. S., Eid, R. E., Diab, H. D. & Redwan, M. S. (2022). Integration of seismic attributes and borehole images for Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous carbonates. In SPE Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference https://doi.org/10.2118/211667-MS

Shazly, T. F. & Abd Elaziz, W. Petrophysical evaluation of the Upper Cretaceous section in Abu Rudeis-Sidri Area, Gulf of Suez, Egypt using well logging data. J. Appl. Geophys. 7, 1–14 (2010).

Hantar, G. (1990). Geology of Egypt 293–327.

Shahin, A. N. Undiscovered petroleum reserves in North Western Desert, Egypt. in 1st International Conference on Geology of the Arab World, GUPCO, Cairo University (1992).

Shalaby, M. R., Hakimi, M. H. & Abdullah, W. H. Organic geochemical characteristics and interpreted depositional environment of the Khatatba Formation, northern Western Desert, Egypt. AAPG Bull. 96(11), 2019–2036. https://doi.org/10.1306/04181211178 (2012).

Shalaby, M. R., Hakimi, M. H. & Abdullah, W. H. Diagenesis in the middle Jurassic Khatatba formation sandstones in the Shoushan Basin, northern Western Desert Egypt. Geol. J. 49(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.25129(2024) (2014).

Eid, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M., Amer, M. & Metwally, A. 3D structural modeling using seismic data and well logs for Khatatba reservoir in Matruh-Shushan Basin, North Western Desert. Egypt. Scientific Reports 13(1), 20158. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47487 (2023).

Dowdle, W. L. & Cobb, W. M. Static formation temperature from well logs - An empirical method. J. Pet. Technol. 27(11), 1326–1330. https://doi.org/10.2118/5036-PA (1975).

Aal, A. A. et al. Tectonic evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean Basin and its significance for hydrocarbon prospectivity in the ultra-deepwater of the Nile Delta. Lead. Edge 19(10), 1086–1102 (2000).

Ali, W. A., Deaf, A. S. & Mostafa, T. 3D geological and petrophysical modeling of Alam El-Bueib formation using well logs and seismic data in Matruh field, northwestern Egypt. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6849. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56825-5 (2024).

Amer, M., Mabrouk, W. M., Soliman, K. S., Noureldin, A. M. & Metwally, A. Three-dimensional integrated geo-static modeling for prospect identification and reserve estimation in the middle Miocene multi-reservoirs: A case study from Amal Field, Southern Gulf of Suez Province. Nat. Resour. Res. 32(6), 2609–2635 (2023).

Barakat, M. K. & Nooh, A. Z. Reservoir quality using the routine core analysis data of Abu Roash “C” in Badr El Din-15 oil field, Abu Gharadig basin, North Western Desert Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 129, 683–691 (2017).

Barakat, M. K., El-Gendy, N. H. & El-Bastawesy, M. A. Structural modeling of the Alam EL-Bueib Formation in the jade oil field, Western Desert Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 156, 168–177 (2019).

Chikiban, B., Kamel, M. H., Mabrouk, W. M. & Metwally, A. Petrophysical characterization and formation evaluation of sandstone reservoir: A case study from Shahd field, Western Desert Egypt. Contrib. Geophys. Geodesy 52(3), 443–466 (2022).

EGPC (Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation) (1992). Western Desert, oil and gas fields. A comprehensive overview. Presented at 11th EGPC Petroleum Exploration and Production Conference

El Awdan, A., Youssef, F. & Moustafa, A. R. (2002). Effect of Mesozoic and tertiary deformations on hydrocarbon exploration in the northern Western Desert, Egypt. In American Association of Petroleum Geologists International Meeting

Ela, N. A., Tahoun, S. S., Fouad, T., Mousa, D. A. & Saleh, R. Source rock evaluation of Kharita and Bahariya formations in some wells, North Western Desert, Egypt: Visual palynofacies and organic geochemical approaches. Egypt. J. Pet. 27(4), 455–465 (2018).

El-Khadragy, A. A., Shazly, T. F., Ramadan, M. & El-Sawy, M. Z. Petrophysical investigations to both Rudeis and Kareem formations, Ras Ghara oil field, Gulf of Suez Egypt. Egypt. J. Pet. 26(2), 269–277 (2017).

Hassan, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Farhoud, K. M. Petrophysical analysis for Ammonite-1 well, Farafra Area, Western Desert, Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 7(12), 5107–5125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-013-1123-y (2014).

Noah, A. Z. & Shazly, T. F. Integration of Well logging analysis with petrophysical laboratory measurements for Nukhul formation at Lagia-8 well, Sinai Egypt. Am. J. Res. Commun. 2(2), 139–166 (2014).

Dowdle, W. L. & Cobb, W. M. Static formation temperature from well logs - An empirical method. J. Petrol. Technol. 27(11), 1326–1330 (1975).

Metwally, A. M. H., Abuzaeid, M. S., Mabrouk, W. & Khalil, M. H. Petrophysical analysis for the well logging data; Case study from Matruh basin, western Desert Egypt. Egypt. J. Appl. Geophys. 19, 6–11 (2019).

Noah, A. Z. & Shazly, T. F. (2014). Integration of well-logging analysis with petrophysical laboratory.

Pickett, G. R. (1972). Practical formation evaluation. GR Pickett.

Said, R. The geology of Egypt: Balkema 734 (Brookfield, 1990).

Sarhan, M. A. & Abdel-Fattah, M. I. Integrating well logs and seismic data for a comprehensive geophysical appraisal of post-Albian oil reservoirs in the SWQ-4X well, Gindi Basin, Egypt. Egypt. J. Pet. 33(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.62593/2090-2468.1021 (2024).

Schlumberger, L. I. Principles and Application: Schlumberger Wireline and Testing 21–89. (1989).

Schlumberger. Geology of Egypt (1984). Presented at Well Evaluation Conference, Cairo.

Abdel-Fattah, M. I. Impact of depositional environment on petrophysical reservoir characteristics in Obaiyed Field, Western Desert Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 9301–9314 (2015).

Abdel-Fattah, M., Gameel, M., Awad, S. & Ismaila, A. Seismic interpretation of the Aptian Alamein dolomite in the Razzak oil field, Western Desert Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 4669–4684 (2015).

Radwan, A. A., Abdelwahhab, M. A., Nabawy, B. S., Mahfouz, K. H. & Ahmed, M. S. Facies analysis-constrained geophysical 3D-static reservoir modeling of Cenomanian units in the Aghar Oilfield (Western Desert, Egypt): Insights into paleoenvironment and petroleum geology of fluviomarine systems. Mar. Pet. Geol. 136, 105436 (2022).

Attia, M. M., Abudeif, A. M. & Radwan, A. E. Petrophysical analysis and hydrocarbon potentialities of the untested Middle Miocene Sidri and Baba sandstone of Belayim Formation, Badri field, Gulf of Suez Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 109, 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2015.05.020 (2015).

Abudeif, A. M., Attia, M. M. & Radwan, A. E. New simulation technique to estimate the hydrocarbon type for the two untested members of Belayim Formation in the absence of pressure data, Badri Field, Gulf of Suez Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 9(3), 218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-015-2082-2 (2016).

Abudeif, A. M., Attia, M. M., Al-Khashab, H. M. & Radwan, A. E. Hydrocarbon type detection using the synthetic logs: A case study, Baba member, Gulf of Suez Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 144(176–182), 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2018.04.017 (2018).

Radwan, A. E., Abudeif, A. M. & Attia, M. M. Investigative petrophysical fingerprint technique using conventional and synthetic logs in siliciclastic reservoirs: A case study, Gulf of Suez basin Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 167, 103868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2020.103868 (2020).

Osman, W., Kassab, M., ElGibaly, A. & Samir, H. Petrophysical evaluation of sandstone gas reservoir using integrated well logs and core data for the lower Cretaceous Kharita formation, Western Desert. Egypt. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 11(10), 3723–3746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-021-01276-1 (2021).

Metwally, A. M., Mabrouk, W. M. & Mahmoud, A. I. A numerical approach to accurately estimate water resistivity (Rw) and saturation (Sw) in shaly sand formations. Contrib. Geophys. Geodesy 52(3), 423–441 (2022).

Metwally, A. M. et al. Formation evaluation of Abu Madi reservoir in Baltim gas field, Nile Delta, using well logs, core analysis, and pressure data. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46039-6 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Egyptian General Petroleum Cooperation (EGPC) and Khalda Petroleum Company for allowing the dataset used in this research paper, and appreciately express their thanks to Geophysics Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, for giving acccess to all the necessary software resources to accomplish this work, using Schlumberger Ltd. TechLog software for well data interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaodong Ma and W. M. supervised the work. A. I. M and W. M. developed the methodology, and A. M. A. I. M was responsible for preparing the figures. A. I. M, W. M., and A. M. were the primary contributors to writing the main text. All authors participated in reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmoud, A.I., Ma, X., Mabrouk, W.M. et al. Petrophysical analysis and pressure gradients reveal hydrocarbon potential in the Paleozoic pre-rift of the PTAH Oil Field, Egypt. Sci Rep 15, 17818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89382-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89382-6