Abstract

Myrtus communis L, is an edible medicinal plant with fruit berries used to manufacture liquors, aromatise wine, and sweet foods, beside several folk-medicinal uses. The plant is also endemic to Libya, holds promise for its medicinal properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, wound healing, and appetising effects. This work aims to explore the phytoconstituents present in the seeds and fruit peels of Myrtus communis L by GC-MS and LC-ESI-MS analysis, respectively. The work also demonstrated the in vitro and in silico antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities of the plant extracts. GC-MS analysis indicated the presence of 11 fatty acids in the myrtle seeds representing 78.61% of the total seeds’ fatty acid contents, where the unsaturated linolenic acid (C18:3) was the major fatty acid (23.11%). Moreover, seven anthocyanins were identified by the LC-ESI-MS analysis in the fruit peels with relative percentage of 59.84% related to the total peaks area in the positive ion mode chromatogram. Among the identified compounds, petunidin 3-O-glucoside and Malvidin 3-O-rutinoside were the most abundant anthocyanins at the relative percentage of 12.48% and11.87%, respectively. Antioxidant assay showed that the ethanolic extract of the Myrtus fruit peels exhibited higher DPPH-free radical scavenging activities compared to the chloroform extract of the seeds (6.89 ± 0.12 and 2.65 ± 0.03, respectively). Similarly, the fruit peels extract was induced higher ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) compared to the seeds extract (4.87 ± 1.02 and 2.10 ± 0.9, respectively. The fruit peels ethanolic extract was exhibited greatest inhibitory effect against tyrosinase enzyme with IC50 126.35 ± 0.92 compared to the activity of seeds extract at the IC50 135.27 ± 1.23. The tested extracts displayed lower level of tyrosinase inhibition activity compared to the standard arbutin (IC50 76.9 ± 0.0). The results of molecular docking simulations suggest that anthocyanins, particularly Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, exhibit significant binding affinity to the tyrosinase enzyme and could potentially serve as effective natural inhibitors. These compounds may interfere with the enzyme’s catalytic activity by interacting with key residues in the active site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxidative stress is a harmful condition resulting from the accumulation the free radical species, including ROS/RNS (oxygen/nitrogen free radicals) and the non-radical reactive species, such as hydrogen peroxide1,2. Whereas ROS/RNS are generated from both endogenous (mitochondria, NADPH oxidases) and/or exogenous sources3,4. The sources of exogenous reactive species are dietary factors, ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, ionizing radiation, toxins, and drugs, water and air pollutants and other factors such as smoking5. Reactive species and other oxidative stress factors are primarily linked to most of the chronic diseases, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular disorders, and diabetes1,6. Furthermore, it has been established that the emergence of dermatological diseases, which in turn promote the development of skin illnesses including dermatitis, skin cancer, and skin ageing, were caused by oxidative stress, which can be directly potentiated by either an excess of ROS generation or a depletion of the defence system7,8. The reports also indicate the crucial role of the ROS in the regulation of melanogenesis, which results in the induction of skin hyperpigmentation. An essential enzyme in mammalian melanogenesis is tyrosinase7.

There are known important roles for the medicinal plant products in the capturing oxidative stress and protection of the body against chronic diseases associated with the oxidative damage of the soft tissues and cells9,10. Both research and applications have been established the beneficial effect of these plants owing to their antioxidant natural contents, which have the ability to oppose and decrease the oxidation processes of compounds that can result in the production of free radicals11,12,13,14. In that context, numerous researches have demonstrated the efficaciousness of antioxidants as anti-aging and anti-pigmenting agents15,16.

The Myrtaceae family comprises over 5500 species of a woody flowering plants, which are categorized into 144 genera and 17 tribes. The genus Myrtus is a member of this family and can be found in Asia, North Africa, and Europe. Myrtus communis L, the plant with the common name “myrtle shrub” is one of the most frequently mentioned varieties of the genus Myrtus in traditional literature and widely growing in the northeast of Libya with a local name of “Myrseen”17. The plant is also native to the Mediterranean region18. In recent years, M. communis as a traditionally known and aromatic plant has drawn a lot of attention due to the popularity of the liqueurs made from its leaves (white liqueur) and berries (red liqueur). In addition, the leaves of the plant are used the preparation of salads, stews, and roasts. The ripe fruit is edible and has been used to manufacture liquors, aromatise wine, and sweet foods, and spice meats and sauces in place of black pepper19,20,21,22. The species, M. communis, is also used medicinally for cough, dental disorders, constipation, and stomachic23. The Arabic term “Eshbet Al-Suker,” which translates to “herb of diabetes” in English, also refers to the use of this species for treating diabetes24. Additionally, Libyans have long utilized the leaves and fruits to treat liver disorders, gingivitis, gastritis, rheumatism, the common cold, and acne24,25. Researchers have also reported the plant’s hypoglycemic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and appetizing effects, as well as its external use to promote wound healing26.

The presence of substantial levels of flavonoids, such as quercetin, chrysin, catechin, and myricetin derivatives, has led to the plant’s widespread use in traditional medicine and its biological activities. The plant also contains biologically active anthocyanins and phenolic acid derivatives, such as galloyl-glucosides, ellagitannins, galloyl-quinic acids, caffeic, gallic, and ellagic acids. These biologically active constituents appear to be involved in the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which makes plant extracts, such as those from myrtle berries and leaves, appealing to both consumers and researchers15,27. The plant also contains volatile constituents such as α-pinene, geranyl acetate, linalool, and 1,8-cineole, and fatty acids such as linoleic, stearic, palmitic, and oleic acid, in its various organs, which also contribute to the its biological importance28.

Reports indicate that the plant species, M. communis, which grows in Libya, possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects24,29. This study looked at the phytochemicals that are found in M. communis. Specifically, it looked at the fatty acids using GC-MS and the anthocyanins using LC-MS/MS in the plant’s seeds and fruit extracts. Based on our review of the relevant literature, this appears to be the first study investigating the plant seeds and fruit constituents. The study also conducts in vitro and in silico tests on the antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibition activities of the plant seeds and fruits, with the aim of demonstrating the plant’s potential benefits for skin disorders, including hyperpigmentation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

National and international guidelines for the collection of wild plants, including responsible collecting, have been taken into consecration during plant collection30. Myrtle fruits were gathered in December 2023, during the fruit’s maturation phase, from Shahat, the highest place in Aljabal Alakhther (Fig. 1). The plant sample was afterward examined by Dr. Houssein Eltaguri, Botany Department, Benghazi University for detailed identification. A voucher specimen under the number of #PPS-2405 was deposited in Pharmacognosy and Natural Products Laboratory at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Assalam University.

Extraction procedure

The Myrtus fruit’s peel and seeds were manually separated, and all samples were dried at 40 °C in an oven. The most popular and preferred drying technique for a lab-scale experiment is hot-air oven drying at temperatures starting from 40 °C and not exceeding 60 °C31. This method of drying has been used for several aromatic plants and showed preservation of their aroma and other bioactive compounds31. In addition, the oven drying technique has been found to be the optimal method for the extraction of the phenolic compound with maximal antioxidant activity32. Along with this, Rahimi et al.. dried Myrtus communis leaves at 40 °C in an oven and found that the volatile plant materials were preserved33. Following their removal from the oven, they were powdered. Next, 500 mL of acidified ethanol and chloroform, respectively, were utilized to extract 100 g of fruit peel and seed separately by using Soxhlet apparatus34. Whatman paper (No. 1) was used for filtering the extracts and the solvents were removed at 40 °C using a rotating evaporator. Before being used, the crude extracts were put into ambered glass bottles and kept at -20 °C.

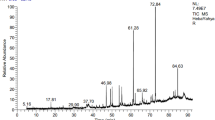

GC-MS analysis of the saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of Myrtus communis L. Seeds

The fatty acid composition of M. communis L seeds were analysed by gas chromatograph (GC) Clarus 500 with an autosampler (Perkin Elmer, USA) equipped with fused silica capillary SGE column (30 m 3 0.32 mm, ID 3 0.25 mm, BP20 0.25 μm, USA). The detector type is lame ionization with 220 °C temperature, while the injector temperature was 280 °C. The sample size was 1 mL, and the carrier gas were controlled at 16 ps. The split ratio was 1:100. By comparing the retention times (Rt) of the unknown fatty acids (FA) to the references that were available and subjected to a comparable analysis, the FAs were identified. Using a computer integrator, peak area measurement was used to perform the quantitative estimation35.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the anthocyanin composition of Myrtus communis L. fruit peels

Shimadzu ExionLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used for the fruit peel extract’s scanning. The machine was equipped with a TurboIonSpray, SCIEX X500R QTOF (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Precisely, 1 mg of the extract was dissolved in 2 mL of DMSO and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 2.0 min. An aliquot of 10 µL of the plant extract was injected. The instrument was operated using ion-source-gas-1, 50 psi, ion-source-gas-2, 50 psi, and ion-funnel-electrospraysource. The capillary voltage of the instrument was operated at (3500 V), and the nebulizer gas at (2.0 bar). The nitrogen flow rate was adjusted at (9 L/min), with dry temperature (200 C). The mass accuracy was less than 1 ppm, the mass resolution was 50,000 FSR (Full Sensitivity Resolution), and the TOF repetition rate was up to 20 kHz. The chromatographic separation was performed on InertSustain by using C18 reverse-phase (RP) column. The gradient elution technique was used at total run time of 40 min. The mobile phase consisting A as 0.1% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B as formic acid in acetonitrile, the flow rate was adjusted at 0.6 mL/min36.

Antioxidant assays

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) scavenging activity

According to the literature37, 5 µL of plant extract, prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL, was mixed with 150 µL of newly prepared DPPH reagent (freshly prepared by dissolving 2 mg with 51 ml of methanol HPLC grade). The mixture was kept in the dark place for thirty minutes. The DPPH colour downshift was measured three times independently at 517 nm, and the DPPH scavenging effect was measured as Trolox equivalent from the calibration cure of the Trolox. The data is shown as mean ± SD.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The assay was performed in compliance with the published procedure38. The TPTZ working reagent (190 µL) was added to 10 µL of the volatile oil (10 mg/mL) on a 96-well plate. The mixture was then allowed to sit at room temperature for 30 min before being measured at 593 nm. The reagent was made up of acetate buffer (300 mM PH = 3.6), TPTZ (10 mM in 40 mM HCl), and FeCl3 (20 mM). The method was conducted in triplicate and Trolox equivalent in milligrams was used to test the FRAP extract activity.

Determination of tyrosinase inhibitory properties

A spectrophotometric technique was utilized to test the tyrosinase inhibitory action39. The arbutin was used as a reference drug to evaluate the sample’s tyrosinase inhibitory activity. Aqueous phosphate buffer (pH ¼ 6.8; I ¼ 0.01 M), a mixture of 2 mL L-tyrosine solution (0.244 mM), and 0.9 mL 50% methanol solution of inhibitor were prepared. An equivalent volume of 50% methanol solution was used for the control sample in place of the inhibitor solution. By adding 0.1 mL of the aqueous mushroom tyrosinase solution (0.1 mg/mL) L-tyrosine was oxidised. The samples and control mixture were incubated at 37 °C for ten minutes, before being measured using spectrophotometry and the dopachrome appearance was tracked at 475 nm. IC50 was used to measure the impact on tyrosinase inhibition. The following formula (Eq. 1) was used to calculate the percentage of tyrosinase activity inhibition:

A sample 475 and A control 475 were the absorbance values in the absence and presence of inhibitors.

Molecular Docking

In this research, the aim was to investigate the molecular mechanisms of how anthocyanin compounds from M. communis L fruit peels inhibit tyrosinase (Fig. 2). The molecular docking simulations were conducted using AutoDock 4.2.6 40. to understand this process. For the protein mode of tyrosinase, two crystal structures of tyrosinase (PDB IDs: 2Y9W and 2Y9X)41 were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Of these, 2Y9W represents the enzyme in its native state, while 2Y9X displays the tyrosinase-tropolone (inhibitor) complex. The 2Y9X structure was selected for our molecular studies due to its more precise structural information regarding the enzyme’s active site, which is occupied by the inhibitor41. The preparation of both the protein and ligands for the docking simulations was carried out using AutoDockTools 1.5.7 42. Initially, the protein crystal structure was loaded into AutoDockTools 1.5.7, where polar hydrogens were added, and Kollman charges43 were assigned, further enhancing the accuracy of the protein representation. Subsequently, each ligand molecule was loaded separately, and Gasteiger charges44 were assigned, taking into account the specific chemical properties of each ligand. Furthermore, A grid box (grid points of 40 × 40 × 40 with a spacing of 0.375 Å) was centered on the potential pocket defined by the centrally located co-crystallised inhibitor (tropolone).

Finally, Molecular docking simulations were performed using standard settings and a Lamarckian genetic algorithm45. The simulations were conducted over 100 iterations. Subsequently, the results were analysed by examining the AutoDock log files. Docked ligands with the lowest binding energies were prioritized, and the conformer exhibiting the most favorable binding pose was selected. To enhance the reliability of our selection, the conformer with the highest cluster population was chosen. The selected conformers were then visualized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 16.1 46 to analyse the binding interactions between the identified compounds, the reference compound (tropolone), and the tyrosinase protein.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. The mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) were calculated from at least three independent experiments to ensure reliability and accuracy of the results.

Results and discussion

GC/MS analysis of the saturated and unsaturated fatty acids of Myrtus communis L. seeds

Fatty acid analysis revealed the presence of 11 different fatty acid constituents, representing 78.61% of the total fatty acid content in the myrtle seeds (Table 1). The analysis was displayed also that saturated fatty acid content was greater than unsaturated fatty acid content. The analysis shown that the predominant saturated fatty acid, palmitic acid (C16), which accounts for 18.72% of total fatty acids. Concerning poly unsaturated fatty acid, linolenic acid (C18:3) was the major fatty acid, which represents (23.11%). However oleic acid (C18:1) and Behenic acid (C22) showed the lowest concentrations, with (2.14 and 1.48%) respectively. The current data for the fatty acids profile is matched the outcomes that stated by Wannes et al.47. Furthermore, it was discovered that oleic and palmitic acids were the primary fatty acids in myrtle fruits. Our findings were consistent with the reported data of Cakir (2004), who also reported the presence of myristic acid in valuable concentration48. The fatty acid contents of the plant seeds might be contributed in the common biological activity and known medicinal use of the plant, especially for the skin disorders49. The presence of the saturated and unsaturated fatty acids in the plant seeds also reflect their potential use as food source, however, higher proportion of the saturated fatty (42.55%) acids, including palmitic and stearic acids might be raise a health concern related to the cardiometabolic and liver diseases50. On the other hand, literature demonstrated that long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, are essential to be consumed through diet in order to promote human health. These are capable of fighting a wide range of ailments, including the diseases of digestive system, heart and nervous system, inflammatory responses, and specific cancers like colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer51. The significance of these polyunsaturated n-3 fatty acids from myrtle’s seeds might be attributed to their anti-inflammatory properties through blocking the synthesis of eicosanoids from arachidonic acid and the expression and production of plasma proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and several other interleukins that exacerbate inflammation52. Thereby, myrtle seed lipids may be significant for a range of health benefits due to their fatty acid profile and high PUFA concentrations.

LC-ESI-MS for Myrtus communis fruit peels extract

The anthocyanins extracted from M. communis L berries were subjected to positive ion electrospray analysis. The analysis resulted in the identification of 7 anthocyanin compounds with a total relative percentage of 59.84% of total calculated peaks area in the positive ion mode chromatogram of the extract (Table 2). These results indicated the higher representation of anthocyanins in the plant fruits. It can be observed that the dark blue colour of M. communis L. fruit may be caused by the fruit’s high concentration of components with purple pigments, specifically glycoside derivatives of petunidin and malvidin53.

Since anthocyanins are naturally positively charged, the positive ion mode was chosen for the identification of anthocyanins in myrtle berries based on the LC-ESI-MS ionisation and fragmentation patterns for the target chemicals. The precise mass measurements of the molecular ions [M]+ from the single TOF-MS analysis were used to first speculatively identify the anthocyanins that corresponded to the peaks (520 nm) in the HPLC-DAD chromatograms. Moreover, using the fragment pattern data, LC-MS2 studies were performed for structural identifications. In addition, each discovered constituent’s mass fragmentation pattern, molecular ion peak, and MS/MS fragments were compared to data from the literature and library.

Petunidin 3-O-glucoside was the major anthocyanin in the plant at the relative concentration of 12.48%. The compound molecular ions peaking at m/z 479 and fragment ions mass peaks at 317 MS/MS (m/z) were represented in the mass chromatogram, which were provoked by the loss of a glucose unit and corresponded to the aglycons. These fragments were reported to be characteristic for the compound and the aglycon fragmentations resemble those that have been documented by Scorrano et al. (2017)54. The main health benefits of petunidin 3-O-glucoside are due to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and possibly anticancer properties. Furthermore, it could be benefit for people with diabetes by lowering blood sugar levels, and cardiovascular disease55. In addition, malvidin 3-O-rutinoside was found as the second most prevalent in the extract with molecular ion peak at m/z 493 and fragment masses at m/z 331 and 270, which were reported as characteristic fragments for the compound. The literature claimed that malvidin and its glycosides have strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects54. In contrast, common molecular ion peaks (579, 595, 433, and 449) were identified in myrtle fruits extract and assigned for pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside respectively (Table 2). The mass spectra of cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside (Rt 15.92 min, ) showed breaking of the rutinoside indicated by the existence of a molecular ion peak at m/z 595.53 [M + H]+ and the fragment’s mass peak at m/z 287 [M-rutinoside)]+. Among the identified anthocyanins, the lowest concentration (%3.54) was found for cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (Rt 23.56 min). Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside was identified based on the presence of molecular ion mass of 449 [M]+ and the mass fragment unit of 287 [M-glucose]+, which tentatively confirming the compound structure36. The pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside and pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside (Rt 11.92 and 26.93) were identified by the presence of m/z 579 and 433.24 [M + H]+ and mass fragments at m/z 271, thereby indicating the aglycone part of the compound, and detachment of the rutinoside and glucose moieties, respectively56. These current results confirm the earlier findings, which showed that the most prevalent anthocyanins in myrtle were petunidin, delphinidin, and malvidin derivatives57 with varying concentrations. However, a study by Alam et al. (2021) reported that cyanidin is the most abundant anthocyanin in myrtle edible fruits, followed by pelargonidin, peonidin, delphinidin, petunidin, and malvidin58.

The results also indicated the health benefits of the plant fruits owing to the presence of anthocyanins. The anthocyanins of different origins have been reported for multi-health functions including their beneficial role in the hypertension, inflammation, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and liver diseases59. They have also been reported as skin repairing and anti-aging substances60. The identified anthocyanins (the glycosylated anthocyanidins) such as Cyanidin − 3-O- glucoside have also been reported to be degraded by the gut microbiota to protocatechuic, gallic, syringic acid, and 3-O-methylgallic acids, that exhibited better anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity compared to the original anthocyanins59.

Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibition activities

Antioxidant capacity of M. communis L fruit peels and seeds were assessed using the DPPH and FRAP assays to measure the free radical scavenging and reducing activity of the plant extracts61. The results showed in Table 3 indicating that the antioxidant activity of the samples varied depending on the used part of plant and type of extracts. In that context, the ethanolic extract of the Myrtus fruits exhibited higher free radical scavenging activities compared to the chloroform extract of the seeds with DPPH radical scavenging effect of 6.89 ± 0.12 and 2.65 ± 0.03, respectively. Similarly, the results of the FRAP assay indicated that the Myrtus fruits have a superior antioxidant and transition metal reducing activities than the seeds extract with FRAP values of 4.87 ± 1.02 and 2.10 ± 0.9, respectively. Antioxidant capacity of different parts from M. communis L has been reported in previous studies. Different extracts of myrtle fruits and seeds have been extensively studied for their antioxidant activity. Study by Serce et al.62, revealed that the methanol extracts of M. communis fruits exhibited good activity with IC50 values between 2.34 and 8.24 µg/ml. Moreover, several other researches have been shown that the methanolic extract of M. communis L fruits possess a distinguished free radical scavenging activity26,63,64. Previous research has also reported strong correlation between the phenolic compounds content and antioxidant activity of myrtle fruits65. The presence of the well-established antioxidant compounds, anthocyanins, in the fruit extract, identified by the LC-ESI-MS analysis (Table 2), is responsible for the plant fruit ethanolic extract’s superior antioxidant activity59. The LC-ESI-MS analysis revealed the presence of 59.84% of the anthocyanins, including petunidin 3-O-glucoside (12.48%) in the fruit extract, which are known for their free radical scavenging and transition metal-reducing activities66. On the other hand, the chloroform extract of the seeds was found to be rich in the fatty acids (Table 1), which have higher nutritive values but lower levels of antioxidant activity compared to anthocyanins59.

The fruit peels and seeds of M. communis L were examined for their ability to inhibit tyrosinase enzyme. Arbutin was used a positive control, a well-known tyrosinase inhibitor and is currently utilized as a cosmetic skin-whitening preparation39. The tested extracts showed promising level of inhibition against the tyrosinase enzyme. Ethanolic extract of the fruits had greatest inhibitory effect against tyrosinase enzyme with IC50 126.35 ± 0.92 (Table 3).

The synthesis of melanin, which is primarily responsible for the colour of human skin, eyes, and hair, is known as melanogenesis. The most common strategy for the development of melanogenesis inhibitors involves the down regulation of tyrosinase, a crucial enzyme that catalyses a rate-limiting step in the synthesis of melanin67. Fruit peels of M. communis L have an inhibitory effect that may be caused by the high concentration of phenolic compounds, particularly anthocyanins. i.e., petunidin 3-O-glucoside, malvidin 3-O-rutinoside, delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, and pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside. The effects of M. communis L fruits and leaves on the tyrosinase enzyme have been investigated by Uysal et al. and Tumen et al., and recorded that the leaf extracts had reasonable activity68,69. Furthermore, there was a strong positive correlation between the total flavonoid concentration and the potency of tyrosinase inhibition68. Many studies have looked at the ability of anthocyanin extracts from plants to inhibit tyrosinase. One of these studies found that petunidin 3-O-glucoside, which our research identified as a predominant anthocyanin in M. communis L fruit peels, acted as promising potential inhibitor of tyrosinase70. This finding could be making M. communis L fruit a lead crude product for creating novel whitening agent70,71.

In silico molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition activity of the anthocyanin compounds on the tyrosinase enzyme

Molecular docking simulations were conducted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition activity of the anthocyanin compounds on the tyrosinase enzyme. To validate the docking protocol, the co-crystal structure of tropolone was redocked, yielding a Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) value of 1.6 Å, as shown in Fig. 3. RMSD, a measure of the average atomic displacement between the docked pose and the experimentally determined reference structure, serves as a key indicator of docking accuracy. An RMSD value below the commonly accepted threshold of 2 Å confirms the reliability of the docking procedure, ensuring the validity of subsequent interaction analyses and binding predictions72.

Table 4 presents the docking results for eight compounds (Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside, Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, Petunidin-3-O-glucoside, Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside, Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, and tropolone) against tyrosinase. All tested compounds exhibited significant binding affinity towards tyrosinase, with binding energies ranging from − 4.9 to -6.1 kcal/mol, exceeding the energy of tropolone (-4.75 kcal/mol). Amng all of them, Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside displayed the strongest binding affinity (-6.1 kcal/mol), over the other compounds as well as the reference (tropolone). This suggests potentially superior potency compared to the other tested compounds.

2D intermolecular interactions representation of (a) Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside, (b) Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, (c) Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside, (d) Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, (e) Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, (f) Petunidin-3-O-glucoside, (g) Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside and (h) Tropolone, docked within tyrosinase (PDB ID: 2Y9X) binding site. Generated by Biovia Discovery Studio visualizer®.

Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside exhibited the lowest binding energy at -6.1 kcal/mol, indicating a strong interaction with the tyrosinase enzyme. It formed hydrogen bonds with ASN260, ARG268, and GLY281, while engaging in hydrophobic interactions with HIS244, VAL248, PHE264, HIS263, VAL283, and ALA286. Pelargonidin-3-O-rutinoside followed closely with a binding energy of -6.02 kcal/mol, interacting through hydrogen bonds with HIS58, MET257, ASN260, THR261, and ARG268 (Fig. 4). The hydrophobic interactions involved HIS244, VAL248, PHE264, HIS263, VAL283, and ALA286. Malvidin-3-O-rutinoside and Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside also showed significant binding energies of -5.86 kcal/mol and − 5.67 kcal/mol, respectively. These compounds formed multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, particularly involving residues such as HIS263, VAL283, and ALA286. The remaining anthocyanins, including Petunidin-3-O-glucoside, Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, and Pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, exhibited binding energies ranging from − 5.31 to -4.9 kcal/mol. Tropolone, the reference compound, displayed the lowest binding energy at -4.74 kcal/mol, with a notable hydrogen bond with HIS259 and hydrophobic interactions involving HIS263 and VAL283 (Fig. 4).

The docking results reveal that anthocyanins generally exhibit stronger binding affinities to the tyrosinase enzyme compared to the reference compound tropolone. Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, with the lowest binding energy, appears to be the most potent inhibitor among the tested compounds. The significant interaction with residues such as ASN260, ARG268, and HIS263, which are crucial for the enzyme’s catalytic activity, suggests that these compounds could effectively inhibit tyrosinase activity by interfering with the enzyme’s active site. The lower binding energy of tropolone, despite being a known tyrosinase inhibitor, indicates that the anthocyanins might offer a more effective natural alternative for tyrosinase inhibition. These findings align with previous studies indicating that anthocyanins can effectively inhibit tyrosinase activity. For instance, Ouyang et al. (2024) isolated anthocyanins from Solanum tuberosum L. and demonstrated their tyrosinase inhibitory activity, with compounds like petanin exhibiting significant inhibition71. Similarly, Wang et al. (2023) conducted a comparative study on the binding behaviors of cyanidin, cyanidin-3-galactoside, and peonidin with tyrosinase, finding that cyanidin exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect73. Additionally, Correia et al. (2021) assessed the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of various anthocyanin-related compounds, identifying several as effective inhibitors74.

These findings suggest that anthocyanins could serve as effective natural inhibitors of tyrosinase, which may have implications in developing treatments for hyperpigmentation disorders or in the cosmetic industry.

Conclusion

The current work underscores the potential of M. communis as a valuable source of bioactive compounds with notable antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase activities. The comprehensive analysis through GC-MS and LC-ESI-MS revealed a rich profile of phytoconstituents in both seeds and fruit peels, particularly highlighting the presence of fatty acids and anthocyanins in these sections of the plant, respectively. The higher antioxidant activities of the fruit peel extract, along with its significant inhibitory effects on the tyrosinase enzyme, suggest that these extracts is attributed to the presence of the anthocyanins and provide beneficial applications for the M. communis fruit peels in both medicinal and cosmetic fields. Additionally, molecular docking simulations indicate that plant anthocyanins may serve as effective natural inhibitors of tyrosinase, paving the way for further research into their therapeutic potential. Overall, M. communis L. holds promise for future studies aimed at harnessing its medicinal properties. As a continuation of the current work, our plan includes chromatographic separation, spectroscopic analysis, structure elucidation of the anthocyanins, along with other constituents of the plant, and investigation of their biological activities.

Data availability

Data are available in the manuscript.

References

Jomova, K. et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 97, 2499–2574 (2023).

Almogbel, E., Aladhadh, A. M., Almotyri, B. H., Alhumaid, A. F. & Rasheed, N. Stress associated alterations in dietary behaviours of undergraduate students of Qassim University, Saudi Arabia. Open. Access. Maced J. Med. Sci. 7, 2182 (2019).

Umber, J. et al. Antioxidants mitigate oxidative stress: a General Overview. Role Nat. Antioxid. Brain Disord 149–169 (2023).

Dhahri, M. et al. Natural polysaccharides as preventive and therapeutic Horizon for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmaceutics 14, 1 (2022).

Wafula, W. G., Arnold, O., Calvin, O. & Moses, M. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, impacts on tissue oxidation and dietary management of non-communicable diseases: a review. Afr. J. Biochem. Res. 11, 79–90 (2017).

Mackawy, A. M. H., Khan, A. A. & Badawy, M. E. S. Association of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene G894T polymorphism with the risk of diabetic nephropathy in Qassim region, Saudi Arabia—A pilot study. Meta Gene. 2, 392–402 (2014).

Chen, J., Liu, Y., Zhao, Z. & Qiu, J. Oxidative stress in the skin: impact and related protection. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 43, 495–509 (2021).

Fahad, D. & Mohammed, M. T. Oxidative stress: implications on skin diseases. Plant. Arch. 20, 4150–4157 (2020).

Akbari, B., Baghaei-Yazdi, N. & Bahmaie, M. Mahdavi Abhari, F. The role of plant‐derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. BioFactors 48, 611–633 (2022).

Mukattash, H. K., Issa, R., Hajleh, M. N. A. & Al-Daghistani, H. Inhibitory effects of Polyphenols from Equisetum ramosissimum and Moringa peregrina extracts on Staphylococcus aureus, Collagenase, and tyrosinase enzymes: in vitro studies. Jordan J. Pharm. Sci. 17, 530–548 (2024).

Mohammed, H. A. & Phytochemical Analysis Antioxidant potential, and cytotoxicity evaluation of traditionally used Artemisia absinthium L.(Wormwood) growing in the Central Region of Saudi Arabia. Plants 11, 1028 (2022).

Mohammed, H. A. et al. Essential oils pharmacological activity: chemical markers, Biogenesis, Plant sources, and Commercial products. Process. Biochem. (2024).

Mohammed, H. A., Emwas, A. H., Khan, R. A. & Salt-Tolerant Plants Halophytes, as renewable Natural resources for Cancer Prevention and Treatment: roles of phenolics and flavonoids in Immunomodulation and suppression of oxidative stress towards Cancer Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 5171 (2023).

Al-Tamimi, O. et al. The effect of roasting degrees on bioactive compounds levels in Coffea arabica and their associations with glycated hemoglobin levels and kidney function in diabetic rats. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. (2024).

Sulaiman, G., Elshibani, F. & Chrysin Flavonoid Molecule Antioxid. Interest. ChemistrySelect 8, 1–15 (2023).

Garcella, P., Wijaya, T. H. & Kurniawan, D. W. Narrative review: herbal nanocosmetics for anti aging. JPSCR J. Pharm. Sci. Clin. Res. 8, 63–77 (2023).

Eltawaty, S. I. et al. Wound healing, in-vitro and in-vivo anti staphylococcus aureus activities of Libyan Myrtus communis l. Eur. J. Biomed. 7, 449–455 (2020).

Dabbaghi, M. M., Fadaei, M. S., Roudi, S., Rahimi, H. B., Askari, V. & V. & R. A review of the biological effects of Myrtus communis. Physiol. Rep. 11, e15770 (2023).

Fadda, A. & Mulas, M. Chemical changes during myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) fruit development and ripening. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 125, 477–485 (2010).

Montoro, P. et al. Characterisation by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry of anthocyanins in extracts of Myrtus communis L. berries used for the preparation of myrtle liqueur. J. Chromatogr. A. 1112, 232–240 (2006).

Berka-Zougali, B., Hassani, A., Besombes, C. & Allaf, K. Extraction of essential oils from Algerian myrtle leaves using instant controlled pressure drop technology. J. Chromatogr. A. 1217, 6134–6142 (2010).

Hacıseferoğulları, H., Özcan, M. M., Arslan, D. & Ünver, A. Biochemical compositional and technological characterizations of black and white myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 49, 82–88 (2012).

Al-Snafi, A. E. et al. The therapeutic value of Myrtus communis L.: an updated review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397, 4579–4600 (2024).

El-Mokasabi, F. The state of the art of traditional herbal medicine in the eastern mediterranean coastal region of Libya. Middle East. J. Sci. Res. 21, 575–582 (2014).

El-Mokasabi, F. Survey of wild trees and shrubs in Eastern region of Libya and their economical value. (2022).

Babou, L. et al. Study of phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of myrtle leaves and fruits as a function of maturation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 242, 1447–1457 (2016).

Franco, A. M. et al. Myrtle seeds (Myrtus communis L.) as a rich source of the bioactive ellagitannins oenothein B and eugeniflorin D2. ACS Omega. 4, 15966–15974 (2019).

Hennia, A., Miguel, M. G. & Nemmiche, S. Antioxidant activity of Myrtus communis l. and myrtus Nivellei Batt. & trab. Extracts: a brief review. Medicines 5, 89 (2018).

Elmestiri, F. M. Evaluation of selected Libyan medicinal plant extracts for their antioxidant and anticholinesterase activities. at (2007).

IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction. (1989). https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/PP-003-En.pdf

Nurhaslina, C. R., Bacho, S. A. & Mustapa, A. N. Review on drying methods for herbal plants. Mater. Today Proc. 63, S122–S139 (2022).

Justine, V. T., Mustafa, M., Kankara, S. S. & Go, R. Effect of drying methods and extraction solvents on phenolic antioxidants and antioxidant activity of Scurrula Ferruginea (Jack) Danser (Loranthaceae) leaf extracts. Sains Malaysiana. 48, 1383–1393 (2019).

Rahimi, M. R., Zamani, R., Sadeghi, H. & Tayebi, A. R. An experimental study of different drying methods on the quality and quantity essential oil of Myrtus communis L. leaves. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 18, 1395–1405 (2015).

Salam, H. S. et al. Potential apoptotic activities of Hylocereus undatus Peel and Pulp extracts in {MCF}-7 and Caco-2 Cancer Cell lines. Plants 11, 2192 (2022).

Ackman, R. The gas chromatograph in practical analyses of common and uncommon fatty acids for the 21st century. Anal. Chim. Acta - ANAL. CHIM. ACTA. 465, 175–192 (2002).

Elshibani, F. A. et al. Phytochemical and biological activity profiles of Thymbra linearifolia: an exclusively native species of Libyan green mountains. Arab. J. Chem. 104775 (2023).

El-Shibani, F. A. A. et al. Polyphenol Fingerprint, Biological activities, and in Silico studies of the Medicinal Plant Cistus Parviflorus L. Extract. ACS Omega (2023).

Elshibani, F. A. et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of Arbutus Pavarii Pampan fruit; in vitro and in Vivo biological evaluations, and in silico investigations. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 39, 2293639 (2024).

Elshibani, F. et al. Determination of Arbutin Content and In-vitro Assessment of Antihyperpigmentation Activity of Microemulsion prepared from Methanolic Extract of the Aerial Part of Arbutus Pavarii Pampan growing in East of Libya. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 9, 1086–1093 (2020).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Ismaya, W. T. et al. Crystal structure of Agaricus Bisporus mushroom tyrosinase: identity of the tetramer subunits and interaction with tropolone. Biochemistry 50, 5477–5486 (2011).

El-Hachem, N., Haibe-Kains, B., Khalil, A., Kobeissy, F. H. & Nemer, G. AutoDock and AutoDockTools for protein-ligand docking: beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) as a case study. Neuroproteomics Methods Protoc. 391–403 (2017).

Singh, U. C. & Kollman, P. A. An approach to computing electrostatic charges for molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 5, 129–145 (1984).

Gasteiger, J. & Marsili, M. A new model for calculating atomic charges in molecules. Tetrahedron Lett. 19, 3181–3184 (1978).

Morris, G. M. et al. Automated docking using a lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19, 1639–1662 (1998).

Systèmes, D. Biovia, discovery studio modeling environment. Dassault Systèmes Biovia San Diego, CA, USA (2016).

Wannes, W. A., Mhamdi, B. & Marzouk, B. Variations in essential oil and fatty acid composition during Myrtus communis var. Italica fruit maturation. Food Chem. 112, 621–626 (2009).

Cakir, A. Essential oil and fatty acid composition of the fruits of Hippophae rhamnoides L.(Sea Buckthorn) and Myrtus communis L. from Turkey. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 32, 809–816 (2004).

Yang, M., Zhou, M. & Song, L. A review of fatty acids influencing skin condition. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 19, 3199–3204 (2020).

Calder, P. C. Functional roles of fatty acids and their effects on human health. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 39, 18S–32S (2015).

Kapoor, B., Kapoor, D., Gautam, S., Singh, R. & Bhardwaj, S. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs): uses and potential health benefits. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 10, 232–242 (2021).

Jabri, M. A., Marzouki, L. & Sebai, H. Myrtle berries seeds aqueous extract abrogates chronic alcohol consumption-induced erythrocytes osmotic stability disturbance, haematological and biochemical toxicity. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 1–10 (2018).

Bueno, J. M. et al. Analysis and antioxidant capacity of anthocyanin pigments. Part II: Chemical structure, color, and intake of anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 42, 126–151 (2012).

Scorrano, S. et al. Anthocyanins profile by Q-TOF LC/MS in Myrtus communis berries from Salento Area. Food Anal. Methods. 10, 2404–2411 (2017).

Kamiloglu, S., Akgun, B. & Petunidin Advances on resources, biosynthesis Pathway, Bioavailability, Bioactivity, and Pharmacology. in Handbook of Dietary Flavonoids 1–34 (Springer, (2023).

Amin, E., Abdel-Bakky, M. S., Mohammed, H. A. & Hassan, M. H. A. Chemical profiling and molecular Docking Study of Agathophora alopecuroides. Life 12, 1852 (2022).

Bagcilar, S. & Gezer, C. Myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) and potential health effects. EMU J. Pharm. Sci. 3, 205–214 (2020).

Alam, M. A. et al. Potential health benefits of anthocyanins in oxidative stress related disorders. Phytochem Rev. 20, 705–749 (2021).

Mohammed, H. A., Khan, R. A. & Anthocyanins Traditional uses, structural and functional variations, approaches to increase yields and products’ quality, Hepatoprotection, Liver Longevity, and Commercial products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2149 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Anti-aging effects and mechanisms of anthocyanins and their intestinal microflora metabolites. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 64, 2358–2374 (2024).

Aroua, L. M. et al. A facile approach synthesis of benzoylaryl benzimidazole as potential α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitor with antioxidant activity. Bioorg. Chem. 114, 105073 (2021).

Serce, S., Ercisli, S., Sengul, M., Gunduz, K. & Orhan, E. Antioxidant activities and fatty acid composition of wild grown myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) fruits. Pharmacogn Mag. 6, 9 (2010).

Sun, J., Lin, L. & Chen, P. Study of the mass spectrometric behaviors of anthocyanins in negative ionization mode and its applications for characterization of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin polyphenols. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 26, 1123–1133 (2012).

Özcan, M. M., Al Juhaimi, F., Ahmed, I. A. M., Babiker, E. E. & Ghafoor, K. Antioxidant activity, fatty acid composition, phenolic compounds and mineral contents of stem, leave and fruits of two morphs of wild myrtle plants. J. Food Meas. Charact. 14, 1376–1382 (2020).

Giampieri, F., Cianciosi, D. & Forbes-Hernández, T. Y. Myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) berries, seeds, leaves, and essential oils: New undiscovered sources of natural compounds with promising health benefits. Food Front. 1, 276–295 (2020).

Xu, M. et al. Recent advances in anthocyanin-based films and its application in sustainable intelligent food packaging: a review. Food Control 110431 (2024).

Pillaiyar, T., Manickam, M. & Namasivayam, V. Skin whitening agents: Medicinal chemistry perspective of tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 32, 403–425 (2017).

Uysal, S., Sinan, K. I. & Zengin, G. Assessment of antioxidant and enzyme inhibition properties of Myrtus communis L. leaves. Int. J. Second Metab. 10, 166–174 (2023).

Tumen, I., Senol, F. S. & Orhan, I. E. Inhibitory potential of the leaves and berries of Myrtus communis L.(myrtle) against enzymes linked to neurodegenerative diseases and their antioxidant actions. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 63, 387–392 (2012).

Yang, S. Y., Kim, J. H., Su, X. & Kim, J. A. The Luteolinidin and Petunidin 3-O-Glucoside: a competitive inhibitor of tyrosinase. Molecules 27, 5703 (2022).

Ouyang, J., Hu, N., Wang, H. & Isolation Purification and tyrosinase inhibitory activity of anthocyanins and their novel degradation compounds from Solanum tuberosum L. Molecules 29, 1492 (2024).

Hevener, K. E. et al. Validation of molecular docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 49, 444–460 (2009).

Wang, M. et al. Comparative study of binding behaviors of Cyanidin, Cyanidin-3-Galactoside, Peonidin with tyrosinase. J. Fluoresc. 34, 1747–1760 (2024).

Correia, P. et al. The role of anthocyanins, deoxyanthocyanins and pyranoanthocyanins on the modulation of tyrosinase activity: an in vitro and in silico approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6192 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors, F.A.E., H.M.A., B.O.A-N, and M.S., were involved in the conception, design, and methodology; N. E-S, E.E-N. and M/A., were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data; F.A.E., H.M.A., B.O.A-N, and R.S., were involved in the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Najjar, B.O., Elshibani, F., Sharkasi, M. et al. Phytochemical analysis, bioactivity, and molecular docking studies of Myrtus communis L. seeds and fruit peel extracts demonstrating antioxidant and anti-tyrosinase properties. Sci Rep 15, 5634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89401-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89401-6