Abstract

Pre-implantation development arrest poses a significant challenge in infertility treatment cycles. This study aims to evaluate the effect of Insulin, Transferrin, Selenium (ITS), and CHIR99021 on arrested human embryos. Arrested human embryos were obtained from the Embryology Department of the Royan Institute. After determining optimal concentrations, the embryos were assigned to control, CHIR99021, and ITS groups and cultured for 48–72 h. The arrest rate significantly decreased in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups compared to the control group (P < 0.05). The developmental rate up to the pre-morula stage significantly increased in the CHIR99021 group compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Additionally, there were significant increases in the expression of SOX2 in the CHIR99021 group and CCNA2 in the ITS group compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Immunofluorescent staining confirmed the expression of NANOG protein in the experimental groups. GSK3 inhibition by CHIR99021 and the application of ITS can alleviate arrest in human embryos, promote cell cycle induction, and enable progression to the blastocyst stage. Comprehensive characterization of these blastocysts in future studies is crucial to support ITS and CHIR99021 probable application in culture systems, particularly for women of advanced maternal age and those experiencing severe male factor infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

in Vitro fertilization (IVF) stands as an assisted reproductive technology (ART) employed to aid infertile couples1. Embryo development arrest pre-implantation poses a frequent challenge in cycles of infertility treatment2. Research suggests that approximately 40 to 50% of embryos in IVF cycles fail to progress to the blastocyst stage and encounter arrest3,4. This arrest, marked by a lack of cell division for a minimum of 24 h, often transpires on the second or third day post-fertilization. The causes of embryo growth arrest can be categorized into two groups: embryonic and parental factors (Fig. 1)5.

Factors Inducing Pre-Implantation Embryo Development Arrest In Vitro. These factors include embryonic disturbances, including chromosomal status, metabolic anomalies, methylation patterns, gene expression, mitochondrial DNA, and small non-coding RNAs, which may trigger developmental arrest. Parental factors also involve diseases causing infertility, disturbances in genetically linked factors, follicular issues, and DNA anomalies.

In a recent study by Yang et al. (2021), arrested embryos were categorized into three types. Type Ι arrested embryos experience disruptions during the Maternal to Zygote Transition (MZT) process, leading to abnormalities in the activation of the embryonic genome. Typically, these embryos are at the one- to three-cell stage. Moreover, a significant number of epigenetic regulators are suppressed in these embryos. Unlike Type Ι arrested embryos, Type ΙΙ and Type ΙΙΙ arrested embryos do not experience issues during the MZT process. Instead, these embryos enter a quiescent cell cycle state, halting at the fourth to the morula stage. Nevertheless, in all three types, disturbances in ribosomes and nucleosomes are noted6.

Considering cell cycle blockade as a primary factor in arrested embryos, this study aims to leverage CHIR99021 small molecule, and ITS capable of stimulating the cell cycle of Type ΙΙ arrested embryos (four to the five-cell stage in this study).

The ITS is a combination of insulin (plays a role in glucose uptake and energy regulation, protein synthesis, and intracellular transport7), transferrin (transports iron and helps reduce toxic levels of oxygen radicals8), and selenium (cofactor for glutathione peroxidase as well as action as an antioxidant9) which is usually used to reduce the need for animal serum as a supplement in basic media in cell culture. It is also used to increase the viability and proliferation of a wide range of cells10 and to improve culture systems11. In addition, CHIR99021 is a small molecule that plays an important role in stem cell derivation, self-renewal12, and regenerative medicine by inhibiting GSK3 13. Since CHIR99021 affects the cell cycle progression of embryonic stem cells14, human pluripotent stem cells15, mesenchymal stem cells16, and cochlear progenitor cells17, we considered it a suitable candidate for this research. Additionally, ITS also affects the cell cycle progression of human keratinocytes18, bovine oocytes19, theca-interstitial cells20, and HL-60 cells21. Therefore, both CHIR99021 and ITS were deemed appropriate for our study.

Results

The study comprised three phases. Initially, the dosage response of ITS and CHIR99021 was investigated to determine the most suitable dosage. In the second phase, embryos from both the control and experimental groups, administered with the appropriate concentration identified in the first phase, were cultured to facilitate the transition of embryos from the arrested state to the blastocyst stage. Finally, in the third phase, the evaluation of blastocyst embryos involved assessing the expression of genes OCT-4, NANOG, SOX2, CDKN1A, and CCNA2 using the qRT-PCR technique. Additionally, the expression of the NANOG protein (inner cell mass [ICM] indicator) was analyzed using the indirect immunofluorescence technique.

ITS and CHIR99021 dose response results

In this study, 10 arrested embryos in CHIR99021 and ITS groups at various concentrations were cultured for 72 h (with five double repetitions at each concentration). The primary criterion for selecting the optimal concentration was based on achieving a higher rate of developmental progress (exit from the arrested state). If rates were equal among concentrations, emphasis was placed on the formation of blastocysts. The rates of embryo exit from arrest and blastocyst formation within 48 to 72 h after culture are outlined as follows:

In the CHIR99021 experimental group, concentrations of 1, 2, 3, and 6 µM were assessed for revealing a significant difference in the rate of embryo exit from arrest. Notably, the concentration of 1 µM exhibited a notable difference compared to other concentrations (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

In the ITS experimental group, evaluations were conducted at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 2%. A significant variation in the rate of progression was observed, particularly with the concentration of 0.5%, showcasing a substantial increase compared to other concentrations (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Based on the results above, concentrations of 1 µM in the CHIR99021 group and 0.5% in the ITS group were chosen for subsequent investigation in the following phase of the study. This phase involved culturing arrested embryos in both the control and experimental groups, and the ensuing impact on embryo morphology and development is detailed in the following sections.

Evaluation of the morphology of arrested human embryos under treatment with ITS and CHIR99021

Figure 2 illustrates images of embryos captured on the first day (the third day of regular culture, depicting arrested embryos) and the final day of blastocyst culture resulting from the cultivation of arrested embryos. Indicators of a high-quality blastocyst include the expansion of the blastocoele cavity, a dense and cohesive ICM, and the presence of numerous sickle-shaped trophectoderm (TE) cells forming a cohesive epithelium22. The evaluation of blastocyst morphology indicates superior performance in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups.

Morphological Changes of Embryos Pre- and Post-Treatment. The images on the left column illustrate arrested embryos pre-treatment, while those on the right column depict resulting blastocysts post-treatment in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups. The blastocyst image in the control group represents a normally developed eight-cell embryo. All visuals were captured using an inverted microscope, showcased at a scale of 10 and 16 micrometers (ZP: Zona pellucida; B: Blastocyst cavity; ICM: Inner Cell Mass; TE: Trophectoderm).

Embryonic development outcomes with selected treatments in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups

In all experimental and control groups, 40 arrested embryos underwent cultivation. In the control group (non-treated arrested embryos), only 10% (four embryos) exited the arrested state. One embryo progressed to the pre-morula stage, while the remaining three embryos experienced fragmentation.

Within the ITS group, 47.5% of the embryos (19 in total) successfully emerged from the arrested state. A substantial decrease in the arrest rate (p = 0.002) and a noteworthy increase in development rate (p < 0.0001) were observed when compared to the control group. Among these embryos, four reached the pre-morula stage, while two progressed to the morula (compaction) stage. Furthermore, seven embryos successfully advanced to the blastocyst stage, whereas six embryos experienced fragmentation (Fig. 3a).

Effects of ITS and CHIR99021 on Progression of Arrested Embryos Development. A comparison of arrested embryos cultivated in the ITS experimental group versus the control group revealed a significant decrease in the arrest rate (p = 0.002) and a notable increase in developmental progress (p < 0.0001) within the ITS group (a). Comparison between arrested embryos cultured in CHIR99021 experimental and control groups revealed significant decreases in the rates of arrest and increases in development (P < 0.0001) relative to the control group. Additionally, the developmental rate up to the pre-morula stage exhibited a noteworthy increase compared to the control (P < 0.0001). Conversely, the rate of fragmentation showed a significant increase compared to the control group (P = 0.05) (b). The analysis was performed utilizing the non-parametric Chi-square test. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001).

In the CHIR99021 group, after embryos cultivation, 82.5% of the embryos (33 in total) successfully exited the arrested state. Comparatively, in this group, there was a noteworthy reduction in the arrest rate (p < 0.0001) and a substantial increase in developmental progress (p < 0.0001) in contrast to the control group. Among these embryos, fifteen reached the pre-morula stage, while six advanced to the morula stage, indicating a significant rise in development up to the pre-morula stage compared to the control (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, the blastocyst formation rate within this group was 12.5% (five embryos), while seven embryos underwent fragmentation, signalling a significant increase compared to the control group (p = 0.05) (Fig. 3b).

Overall, the ITS group displayed a higher blastocyst formation rate. Furthermore, the ITS and CHIR99021 exhibited noteworthy decreases in arrest rates and increases in development rates compared to the control group. In terms of the developmental progress of arrested embryos up to pre-morula stages compared to the control, the CHIR99021 group demonstrated a significant increase.

Evaluation of pluripotency, cell cycle-related genes, and NANOG protein expression in arrested embryos treated with specific doses versus control

In the study’s final phase, gene and protein expression in blastocysts from the experimental groups were evaluated utilizing RT-qPCR and indirect immunofluorescence techniques.

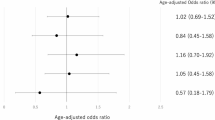

A comparison of pluripotency-related gene expression—such as OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2—and cell cycle-related gene expression—such as CDKN1A (cell cycle inhibitor) and CCNA2 (cell cycle promoter)—between experimental and control groups is depicted in Fig. 4 (The expression levels are shown in Supplementary Table 2). The results reveal that the expression of the OCT4 gene in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups, when compared to the control group (blastocysts derived from PGD embryos), exhibited a non-significant decrease and increase, respectively (p > 0.05). Moreover, the NANOG gene expression in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups, compared to the control group, indicated an increase and decrease, respectively, without displaying a significant difference (p > 0.05). Conversely, the SOX2 gene expression in the control group decreased in comparison to the CHIR99021 group, demonstrating a significant difference (p = 0.01). However, the expression of this gene did not exhibit a notable variation between the control and ITS groups (p > 0.05).

Comparing Pluripotency and Cell Cycle-Related Gene Expression in Blastocysts Between Experimental and Control Groups. The expression of the SOX2 gene in the control group demonstrated a significant decrease in comparison to the CHIR99021 group (P = 0.01). The expression pattern of the CCNA2 gene exhibited a noteworthy decrease in the control group compared to ITS (P < 0.05). Data underwent analysis via ANOVA statistical tests, and error bars were plotted based on SE (**, P < 0.01).

The findings indicate that the expression pattern of the CCNA2 gene in both experimental groups showcased an increase compared to the control group, with the difference being significant solely in the ITS group (p < 0.05). Regarding CDKN1A expression, relative to the control, a descending pattern was observed in the ITS group, while an increasing trend was noted in the CHIR99021 group; however, no significant difference was observed (p > 0.05).

Finally, NANOG protein expression among the experimental groups ITS and CHIR99021 was compared with the control through immunofluorescent staining.

Figure 5 illustrates the NANOG protein expression in the experimental groups compared to the control group. In this study, the ICM was visualized using the NANOG antibody (green), while the nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. The expression of NANOG in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups was confirmed to be similar to that of the control blastocysts (derived from PGD). In addition, NANOG protein cell numbers in these groups demonstrated no significant difference compared to the control group (p > 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

One of the significant methods for addressing infertility among couples is through IVF. The initial successful IVF attempt that led to the birth of a healthy child occurred in 1978 23. A significant obstacle encountered in IVF treatments is the arrest of embryo development before implantation. Human embryos’ developmental potential in Vitro is comparatively lower, resulting in a higher rate of developmental arrest.

Various factors contribute to inducing embryonic developmental arrest, and these factors can be examined at both embryonic and parental levels (Fig. 1). Only a few methods have been suggested to counter developmental arrest thus far. Strategies aimed at addressing this issue include maternal spindle/nuclear transfer24, enhancing culture conditions, employing antioxidants25, and the production of cRNA/siRNA26,27.

In this study, the introduction of ITS and CHIR99021 into the culture medium led to enhanced embryo development and prompted cell cycle advancement. We have an idea that the pathway that is activated in the presence of these two substances is the PI3K signaling pathway. This pathway is triggered by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and G-protein-coupled receptors. RTKs serve as intracellular receptor gaps for growth factor receptors like HER2, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR), and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)28. Upon activation of this pathway by these receptors, Cyclin D-1, one of its targets, becomes activated. By binding to cyclin-dependent kinase proteins, it stimulates progression through the G1/S checkpoint and ultimately facilitates cell proliferation29.

In this study, the ITS medium exhibited superior efficacy compared to other regulators in fostering the development of type ΙΙ arrested embryos up to the blastocyst stage. Comprising insulin, transferrin, and selenium, presumably, the ITS medium potentially owes its ability to overcome embryo arrest to the presence of insulin. Insulin receptors in embryos exhibit activity from the single-cell stage30. It has been confirmed that oocytes and pre-implantation embryos possess transcripts of insulin-like growth factor receptors 1 and 2 (IGFR1/2) and insulin receptor (IR). There is supporting evidence indicating the regulation of pre-implantation development by insulin and insulin-like growth factors secreted from maternal or embryonic sources31.

IGF1 triggers a rapid increase in cyclin D-1, cyclin D-3, and cyclin E proteins. In contrast, these components prompt a reduction in the expression levels of P27 and P57 32. A study investigating mouse embryos treated with insulin, IGF1, and IGF2 revealed an augmentation in protein synthesis and cell numbers31. Additionally, observations indicated that ITS could improve the embryo cleavage rate, promote the formation of four-cell embryos, and foster the development of seven-day blastocysts, consistent with the outcomes obtained in our studies33.

The small molecule CHIR99021 likely activates the PI3K downstream component by inhibiting GSK3. This inhibition eliminates GSK3’s suppressive effect on beta-catenin, thereby preventing the degradation of beta-catenin in the cytoplasm. Consequently, beta-catenin can enter the nucleus and modulate the expression of target genes34.

A 2024 study compared extracellular RNA levels between normal and arrested embryos. The study identified that the BMP signaling pathway is likely involved in the occurrence of the arrested phenomenon35.

In a study conducted by Yang et al. (2021), they partially overcame the arrest of type Ι and type ΙΙ embryos by activating SIRT1 using resveratrol6. Table 1 compares the impact of resveratrol, CHIR99021, and ITS on arrested embryos after IVF.

The expression of OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 genes in blastocyst-stage embryos is indicative of a normal embryo capable of forming the three primary embryonic layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm36. The pluripotent gene expression patterns were assessed in the ITS and CHIR99021 groups and compared to those of the control group. Overall, no significant differences were observed in the expression of these genes in either group when compared to the control group. However, the CHIR99021 group exhibited a notable increase in the expression level of the SOX2 gene compared to the control group. In a study by Adachi et al. (2010) on human embryonic stem cells, excessive SOX2 expression led to their differentiation into trophoectoderm, potentially resulting in reduced NANOG and OCT4 gene expression37. This might explain the decreased NANOG expression in the CHIR99021 group compared to ITS.

The findings suggest that activating the PI3K pathway through ITS leads to the development of embryos expressing essential factors akin to normal blastocysts, indicating their competence for forming a normal embryo. Moreover, in the CHIR99021 group, except for the expression of SOX2, both NANOG, and OCT4, genes were expressed at levels akin to normal blastocysts. This implies that the small molecule CHIR99021 is reasonably successful in providing the crucial factors essential for embryonic development.

In the study by Yang et al., they found that the CCNA2 gene expression in arrested embryos of types ΙΙ and ΙΙΙ decreases in comparison to the corresponding stage in normal embryos. Conversely, the expression of the CDKN1A gene increases. This variance in expression levels is noteworthy6. The CCNA2 gene stimulates cell cycle progression, while the CDKN1A gene hinders the cell cycle. In this study, the CCNA2 gene expression pattern in both experimental groups, in contrast to the control group (normal blastocysts resulting from PGD), shows an increase, with the difference being particularly significant in the ITS group.

On the other hand, the expression of the CDKN1A gene decreased in the ITS group and increased in the CHIR99021 group compared to the control. However, as the variance in CDKN1A expression in both groups compared to the control (normal embryos resulting from PGD) is not substantial, it suggests the beneficial impact of PI3K pathway stimulation in orchestrating an appropriate and typical cell cycle. In Yang’s investigation, the expression of these two genes compared to the control in arrested embryos of types ΙΙ and ΙΙΙ were significant.

Xin Zhang et al. highlighted NANOG’s role in expediting the entry of human embryonic stem cells into the S phase. Elevated NANOG expression leads to increased levels of CDC25A and CDK6, expediting cells’ entry into the S phase38. One of the outcomes observed in this study is the heightened expression of the cell cycle progression-linked gene, CCNA2, in the ITS group when compared to CHIR99021. This increased expression, considering the elevated NANOG expression in the ITS group, can be justifiable.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The small number of human embryos available restricted the evaluation to a limited range of doses. Moreover, the specific role of CCNA2 in development was intended to be assessed through gene knockdown; however, the ethics committee determined that using normal embryos for this purpose was not permissible. Future studies should also incorporate evaluations of the embryos’ karyotype and chromosomal characteristics to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Conclusion

This study aimed to reinitiate the development of human embryos in a state of arrest by supplementing the culture media with CHIR99021, a GSK3 inhibitor, and ITS. Under these conditions, type II arrested embryos demonstrated the ability to progress to the blastocyst stage. Additionally, the embryos exhibited normal expression of most pluripotency and cell cycle genes, along with normal morphological characteristics. Further experiments are required to identify the upstream and downstream effector molecules, which may ultimately elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action.

Materials and methods

Ovulation stimulation and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)

Ovulation stimulation adhered to the standard long protocol for all patients. Oocytes were retrieved via ultrasound-guided transvaginal aspiration under anesthesia between thirty-four to thirty-six hours subsequent to the administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Choriomon; IBSA). Upon removal of cumulus cells, an embryologist assessed the morphological features of each MII oocyte using an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE 300). Subsequently, each MII oocyte was positioned in a SAGE 1-Step medium (Origio). Normal fertilization, confirmed by the presence of two pronuclei and the second polar body, was observed sixteen to eighteen hours post-ICSI. Oocytes displaying one, three, or more pronuclei were deemed abnormal and eliminated. The normally fertilized embryos were cultured, and those with two to five cells on day three were categorized as arrested.

Ethical approval

This experimental study was conducted following patients’ written consent for the donation of arrested embryos for research purposes, in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Royan Institute (Tehran, Iran; Approval Number: IR.ACECR.ROYAN.REC.1402.007).

Arrested embryo culture

The inclusion criteria involved embryos at the 72-hour stage displaying arrested growth, defined by having between four and five cells. In this study, 150 patients each donated one or two embryos that had arrested during the ICSI process. The experimental groups were cultured in SAGE 1-Step medium (REF 67020010 A, Origio) supplemented with ITS medium (41400045, Gibco) (1, 2, and 0.5%), or CHIR99021 small molecule (04-0004-10, Stemgent) (1, 2, 3, and 6 µM). The control group applied the SAGE 1-Step base medium exclusively.

After preparing the culture media for all groups, 10 µL droplets of the specified medium were meticulously dispensed into individual Petri dishes. These droplets were then covered with liquid paraffin (Origio, CooperCompanies, USA) and placed in an incubator at 37 °C with 6% CO2 for 4 h. The cultured embryos were assessed for morphology, examined, and imaged using an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41, Japan). Before being randomly allocated to culture media, the embryos underwent three washes in droplets of SAGE 1-Step base culture medium. Subsequently, the embryos were transferred to an incubator set at 37 °C with 6% CO2 and cultured for 2 or 3 days.

Following the culture period, the embryos’ morphology was reassessed using an inverted microscope. Initially, to establish appropriate dosages for the experimental groups, 10 embryos were cultured at varying concentrations. Through morphological assessments, the optimal concentration for each group was determined, considering the rate at which embryos transitioned from the arrested state to the blastocyst stage. In the subsequent phase, 40 arrested embryos were cultured in each experimental and control group based on the identified effective concentration. Morphological assessments were conducted, evaluating the rate at which embryos exited the arrested state and reached the blastocyst stage. Embryos successfully progressing to the blastocyst stage were preserved for further assessment of gene expression and indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Gene expression and complementary DNA (cDNA) extraction

The expression of the genes OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, CCNA2, and CDKN1A was evaluated in blastocysts from both the experimental and control groups in this investigation (four replicates). Cell RNA Protect (Qiagen, Germany) was utilized to store blastocysts from both the control and experimental groups until RNA extraction at -80 °C. RNA was extracted from each blastocyst using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germany) in accordance with the protocol provided by the manufacturer. CDNA synthesis was then conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions using the cDNA Synthesis Kit (Smobio, Taiwan).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

mRNA was extracted from the embryos, followed by the synthesis of cDNA. The resulting cDNA was amplified utilizing a mixture containing specific oligonucleotides and SYBR Green (Ampliqon, Denmark). The primers corresponding to the oligonucleotides used are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The analysis focused on evaluating the expression of OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, CCNA2, and CDKN1A genes, with GAPDH serving as the housekeeping gene. To ensure result accuracy, each group underwent four independent laboratory replicates, and each replicate was assessed through duplicate reactions.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining

Blastocyst-stage embryos underwent fixation in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Merck, Germany) at 4 °C for 30 min, followed by treatment with 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco, USA) at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, the embryos were incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in horse serum for 60 min at 37 °C to inhibit nonspecific antibody binding. This was followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C with a primary Nanog antibody (Sc3033, Santa Cruz, USA) at a dilution of 1:100. Following the primary antibody incubation, a secondary Donkey anti-goat antibody (A-11055, Invitrogen, USA) at a dilution of 1:600 was applied for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained using a DAPI solution (Sigma, USA) for 5 min. Thorough washing with Tween (Sigma, USA) in PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was conducted between each step. Images were acquired using a camera (Eclipse 50i, Nikon, Japan) coupled with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis for this research was conducted using SPSS software (version 22). The variables concerning developmental stages and dosage response were evaluated using the non-parametric Chi-square test. Gene expression levels were assessed utilizing analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) and the Tukey test. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was adopted, and the graphs were generated using Microsoft Excel software.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Anwar, S. & Anwar, A.Infertility A review on causes, treatment and management. Womens Health Gynecol. 5, 2–5 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Mutations in PADI6 cause female infertility characterized by early embryonic arrest. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 744–752 (2016).

Alikani, M. et al. Cleavage anomalies in early human embryos and survival after prolonged culture in-vitro. Hum. Reprod. 15, 2634–2643 (2000).

Mohebi, M. & Ghafouri-Fard, S. Embryo developmental arrest: Review of genetic factors and pathways. Gene Rep. 17, 100479 (2019).

Sfakianoudis, K. et al. Molecular drivers of developmental arrest in the human preimplantation embryo: A systematic review and critical analysis leading to mapping future research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8353 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Human embryos arrest in a quiescent-like state characterized by metabolic and zygotic genome activation problems. bioRxiv (2021). 2021.2012. 2019.473390.

Tokarz, V. L., MacDonald, P. E. & Klip, A. The cell biology of systemic insulin function. J. Cell. Biol. 217, 2273–2289 (2018).

Altamura, S. et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis: Lessons from mouse models. Mol. Aspects Med. 75, 100872 (2020).

Steinbrenner, H. & Sies, H. Protection against reactive oxygen species by selenoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1790, 1478–1485 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Insulin–transferrin–selenium as a novel serum-free media supplement for the culture of human amnion mesenchymal stem cells. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 49, 63–71 (2019).

dos Santos Mendonça-Soares, A., Guimarães, A. L. S., Fidelis, A. A. G., Franco, M. M. & Dode, M. A. N. The use of insulin–transferrin–selenium (ITS), and folic acid on individual in Vitro embryo culture systems in cattle. Theriogenology 184, 153–161 (2022).

Taei, A. et al. Enhanced generation of human embryonic stem cells from single blastomeres of fair and poor-quality cleavage embryos via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase β and rho-associated kinase signaling. Hum. Reprod. 28, 2661–2671 (2013).

Delepine, C., Pham, V. A., Tsang, H. W. & Sur, M. GSK3ß inhibitor CHIR 99021 modulates cerebral organoid development through dose-dependent regulation of apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation and migration. PLoS One 16, e0251173 (2021).

Ye, S. et al. Pleiotropy of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition by CHIR99021 promotes self-renewal of embryonic stem cells from refractory mouse strains. PloS One 7, e35892 (2012).

Laco, F. et al. Unraveling the inconsistencies of cardiac differentiation efficiency induced by the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 in human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell. Rep. 10, 1851–1866 (2018).

Govarthanan, K., Vidyasekar, P., Gupta, P. K., Lenka, N. & Verma, R. S. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibitor-CHIR 99021 augments the differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 22, 91–105 (2020).

Roccio, M., Hahnewald, S., Perny, M. & Senn, P. Cell cycle reactivation of cochlear progenitor cells in neonatal FUCCI mice by a GSK3 small molecule inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 5, 17886 (2015).

Mainzer, C. et al. Insulin–transferrin–selenium as an alternative to foetal serum for epidermal equivalents. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 36, 427–435 (2014).

Córdova, B., Morató, R., Izquierdo, D., Paramio, T. & Mogas, T. Effect of the addition of insulin–transferrin–selenium and/or L-ascorbic acid to the. Maturat. Prepubertal Bovine Oocytes Cytoplasm. Maturat. Embryo Dev. Theriogenol. 74, 1341–1348 (2010).

Palaniappan, M., Menon, B. & Menon, K. Stimulatory effect of insulin on theca-interstitial cell proliferation and cell cycle regulatory proteins through MTORC1 dependent pathway. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 366, 81–89 (2013).

Zeng, H. Selenite and selenomethionine promote HL-60 cell cycle progression. J. Nutr. 132, 674–679 (2002).

Ebner, T. et al. Morphological aspects of human blastocysts and the impact of vitrification. J. für Reproduktionsmedizin Und Endokrinologie-Journal Reproductive Med. Endocrinol. 8, 13–20 (2011).

Clarke, G. N. ART and history, 1678–1978. Hum. Reprod. 21, 1645–1650 (2006).

Tang, M. et al. Germline nuclear transfer in mice may rescue poor embryo development associated with advanced maternal age and early embryo arrest. Hum. Reprod. 35, 1562–1577 (2020).

Rodríguez-Varela, C. & Labarta, E. Does coenzyme Q10 supplementation improve human oocyte quality? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9541 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Karyopherin α deficiency contributes to human preimplantation embryo arrest. J Clin. Invest 133. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci159951 (2023).

Jia, Y. et al. Identification and rescue of a novel TUBB8 mutation that causes the first mitotic division defects and infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37, 2713–2722 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Targeting PI3K in cancer: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol. Cancer 18, 1–28 (2019).

Zhao, M. & Ramaswamy, B. Mechanisms and therapeutic advances in the management of endocrine-resistant breast cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 5, 248 (2014).

Riley, J. K. et al. The PI3K/Akt pathway is present and functional in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 284, 377–386 (2005).

Lighten, A. D., Hardy, K., Winston, R. M. & Moore, G. E. Expression of mRNA for the insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in human preimplantation embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 47, 134–139 (1997).

Mairet-Coello, G., Tury, A. & DiCicco-Bloom, E. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes G1/S cell cycle progression through bidirectional regulation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in developing rat cerebral cortex. J. Neurosc. 29, 775–788 (2009).

Smits, A., De Bie, J., Bols, P., Marei, W. & Leroy, J. Effect of embryo culture conditions on developmental potential of bovine oocytes matured under lipotoxic conditions. in Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 18th International Congress on Animal Reproduction (2016).

Thompson, M., Nejak-Bowen, K. & Monga, S. P. Crosstalk of the wnt signaling pathway. Targeting Wnt Pathw. Cancer 51–80 (2011).

Wu, Q. et al. A temporal extracellular transcriptome atlas of human pre-implantation development. Cell Genomics 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100464 (2024).

Wang, Z., Oron, E., Nelson, B., Razis, S. & Ivanova, N. Distinct lineage specification roles for NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. Stem Cell. 10, 440–454 (2012).

Adachi, K., Suemori, H., Yasuda Sy, Nakatsuji, N. & Kawase, E. Role of SOX2 in maintaining pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. Genes Cells 15, 455–470 (2010).

Zhang, X. et al. A role for NANOG in G1 to S transition in human embryonic stem cells through direct binding of CDK6 and CDC25A. J. Cell. Biol. 184, 67–82 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Royan Institute’s embryology department to this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K; Conducted the experiments, analysis, and interpretation of data, illustrated the results, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.N.A; Helped conducte the experiments. F.H and P.EY; Design, verified the analytical methods, Supervised the findings, and Critically revised the manuscript. A.T and SN.H; Helped design the study, verify the analytical methods, and supervise the findings.All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karami, N., Taei, A., Hassani, S.N. et al. The effects of insulin–transferrin–selenium (ITS) and CHIR99021 on the development of pre-implantation human arrested embryos in vitro. Sci Rep 15, 5006 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89460-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89460-9