Abstract

The recent emergence of Oropouche virus (OROV) highlights the importance of understanding insecticide susceptibility in the genus Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). In addition to the vector of OROV, this genus contains many other species that are biting nuisances and vectors of pathogens that affect humans, livestock, and wildlife. With adulticides as the primary method of Culicoides control, there is growing concern about insecticide resistance, compounded by the lack of tools to monitor Culicoides susceptibility. We adapted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) bottle bioassay and field cage trial methods, typically used to monitor insecticide susceptibility in mosquitoes and formulated adulticide efficacy, to evaluate permethrin susceptibility in the widely distributed coastal nuisance species, Culicoides furens. Permethrin caused 100% mortality in C. furens in field and laboratory assays. We identified a diagnostic dose (10.75 µg) and time (30 min) that resulted in 100% mortality in CDC bottle bioassays. Additionally, we determined that no-see-um netting is an effective mesh for field cage trials, allowing for the accurate assessment of Culicoides susceptibility to ultra-low volume applications of formulated adulticides like Permanone 30–30, a widely used adulticide. These methodologies offer essential tools for assessing Culicoides susceptibility, which is crucial for managing populations of Culicoides and preventing the spread of OROV and other pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent emergence and rapid spread of Oropouche virus (OROV) in the Americas1 highlights existing knowledge gaps in the ecology and control of Culicoides biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae)2, including Culicoides paraensis (Goeldi), a confirmed vector of OROV. Once considered endemic to the greater Amazonian Region of South America3, OROV is becoming increasingly prevalent in parts of South America, and recently spread to parts of the Caribbean, posing a significant public health risk outside of its endemic range4. Vector control agencies in the areas of OROV expansion will benefit from understanding whether their established mosquito control practices are effective against anthropophilic Culicoides species.

The genus Culicoides includes species that are not only biting nuisances but also pathogen vectors affecting humans, wildlife, and livestock. Culicoides species transmit around 20 arboviruses and five nematode species of veterinary importance, affecting a wide range of hosts5. Notable arboviruses include African horse sickness virus (AHSV), bluetongue virus (BTV), and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV)5,6. These viruses significantly impact livestock industries across multiple geographical areas, including North America5, Central and South America7, Europe8, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East9.

Globally, vector control relies heavily on chemical adulticides, particularly pyrethrins and pyrethroids like permethrin due to their potency and relative safety for mammals10. Permethrin is widely used for mosquito control in the United States11. Additionally, permethrin is the main active ingredient used for Culicoides control in Florida deer farms, where its frequent use has raised concerns about insecticide resistance12.

Monitoring insecticide susceptibility and resistance in target arthropods is a cornerstone in a successful control program13. Insecticide resistance is often detected through laboratory bioassays such as the World Health Organization (WHO) tube assay and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) bottle bioassay14. These assays are extensively used to monitor resistance in mosquitoes and other vectors of public health significance15. However, standardized protocols for applying these methods to Culicoides are currently lacking. Field-based bioassays, such as “field cage trials”, are recommended to assess the susceptibility of insects to formulated insecticides like adulticides, particularly when resistance is detected in laboratory settings15.

Despite the medical, veterinary, and nuisance importance of many Culicoides species, established protocols for monitoring susceptibility in no-see-ums are lacking. In North America, only a few studies have investigated the susceptibility of Culicoides to adulticides16,17,18. These studies, conducted on Culicoides furens (Poey) populations in Florida, tested the efficacy of ULV sprays containing organophosphates (malathion, naled) and a pyrethroid (resmethrin). Naled was found to be the most effective, achieving 90% mortality at distances up to 106 m, compared to 36 m for malathion and 25 m for resmethrin18. However, a recent survey of Florida mosquito control programs documented higher usage of pyrethrin and the pyrethroid permethrin as adulticide active ingredients as compared to the organophosphates malathion and naled19. Additionally, only one Florida mosquito control program reported using resmethrin in 202019.

Understanding Culicoides susceptibility to insecticides currently used by vector control programs is essential for developing integrated vector control programs. However, studies are limited due to challenges in establishing laboratory colonies of Culicoides and the lack of accredited testing protocols. While 151 Culicoides species are recorded in North America, only Culicoides sonorensis Wirth and Jones is currently colonized20. Standard bioassays like the CDC bottle bioassay and cage field trials are commonly used for mosquitoes, but their applicability to Culicoides is uncertain. We adapted these methods to evaluate the susceptibility of field collected C. furens from Indian River County, FL aiming to establish a diagnostic dose (DD: dose that kills 100% of susceptible mosquitoes within a given amount of time) and diagnostic time (DT: the expected time for the insecticide to cause 100% mortality)15. These parameters were used in CDC bottle bioassays, and we also aimed to identify a suitable mesh for cage field trials.

Methods

Insects

The absence of laboratory colonies of Culicoides have somewhat normalized the use of field-collected specimens21. We tested field collected C. furens, a nuisance species of the eastern U.S. coastal areas, and a putative vector of Mansonella ozzardi in the Caribbean22. These insects were trapped at the University of Florida, Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory (FMEL) in Indian River County (27.5873° N, -80.3733° W) using CDC miniature light traps (BioQuip products, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) equipped with live midge collection chambers on the night prior to the experiment23. Traps were baited with an incandescent light bulb, 2 mL of octenol (1-Octen-3-ol) placed in a 15 mL plastic tube with a piece of cotton wool, and ~ 1 kg of dry ice contained in an insulated 1.89 L beverage container (Igloo Products Corp., Katy, TX). The field collected midges were brought to the laboratory in the morning, and allowed to acclimate to laboratory conditions until the time of the experiment (6–8 h). Field collected midges were provided with cotton rounds soaked with a 10% sucrose solution.

Since reference (known susceptible control) C. furens are unavailable (the absence of laboratory colonies), we used a laboratory-reared strain of Aedes aegypti (L) (strain Orlando 1962) which originated from Orlando, FL (Orange County) as a susceptible control. This strain was originally obtained from colonies maintained at the USDA-ARS CMAVE. The Ae. aegypti were reared in an insectary at 26 °C and 85% relative humidity. Egg papers were placed in plastic trays containing approximately 2 L of tap water at a density of 200–300 eggs per rearing tray. Larvae were maintained on a 1:1 mixture of lactalbumin and yeast ad libitum. Pupae were transferred from larval rearing trays to water-filled plastic cups in 30.5 × 30.5 × 30.5 cm Bug Dorm adult rearing cages (BioQuip, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA). Cotton rounds soaked with 10% sucrose solution were placed inside each cage as carbohydrate source for emerging adults. Female and male mosquitoes between 4 and 8 days old were used in our experiment.

CDC bottle bioassays

CDC bottle bioassays are routinely used to monitor mosquito insecticide susceptibility15. We adapted this method to calibrate the assay for Culicoides by determining the DD and DT for permethrin. Following the CDC protocol15, we prepared permethrin solutions by diluting technical grade permethrin (100% Chem Service Inc., West Chester, PA, USA) in American Chemical Society (ACS) grade acetone (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Each bioassay used five 250-ml clear Wheaton bottles with lids (DWK Life Sciences Inc., Millville, NJ), four coated with 1.0 ml of the permethrin solution and one untreated control coated with acetone only. Bottles were coated by swirling the solution inside and then left to dry on a hot dog roller machine with heat turned off to ensure even coating. Control bottles were capped and rolled before preparing bottles containing insecticide. All bottles were then left open to dry in a dark environment to prevent permethrin photodegradation and moisture build-up15,24. Preliminary observations showed high mortality of C. furens in control bottles when the bioassay was performed within five hours after the bottles were coated. We tested various drying times (5, 10 and 24 h) and found that 24 h of drying were necessary to eliminate control mortality.

As recommended by Brogdon and Chan25, when calibrating the CDC bottle bioassay to determine DD and DT for a new insect, we prepared bottles with a range of permethrin concentrations. Based on the CDC’s recommended DD of 43 µg permethrin/bottle for susceptible Ae. aegypti15,25, and the small size of C. furens in comparison to Ae. aegypti, the permethrin concentrations we tested as possible DD were 43, 21.5, and 10.7 µg permethrin/bottle. Three CDC bottle bioassays were performed for each dose tested, on separate days. The permethrin concentration that killed 100% of the field collected C. furens between 30 and 60 min would be selected as the DD15.

Bottle bioassays were performed simultaneously in separate bottles for susceptible Ae. aegypti and field collected C. furens. Mosquitoes and C. furens were aspirated by mouth into each bottle with the goal of 20 individuals per bottle. Only females of C. furens were included in our experiments. Mortality was recorded every five minutes for the first 15 min and every 15 min thereafter15. After the 2-hrs of exposure, insects were transferred into 0.2 L paper cups with lids and generic mesh to prevent insects from escaping. Insects were provided with a cotton round with water and mortality was then assessed at 24-h post-exposure26.

Field cage trials

Two field trials were conducted between March and April 2023 on a 2-ha plot with low-cut grass at the Indian River County Fairgrounds (27.5874° N, -80.3736° W). Spray missions were performed around dusk (1700 h and 1800 h). We targeted caged susceptible Ae. aegypti and/ or field collected C. furens (Table 1). Permanone 30–30 (30% permethrin, 30% piperonyl butoxide) was applied at maximum rate (0.00785 kg permethrin/ha) (Table 1) using a truck-mounted ULV aerosol generator operated by personnel of the Indian River Mosquito Control District.

Bioassay cages (Fig. 1) consisted of cardboard rings (15.2 cm diameter, 2.5 cm height) covered with mesh on both sides27,28. Three mesh types were tested (Fig. 1): stainless steel (SS) McMaster-Carr, Douglasville, GA), no-see-um netting (NN) (Seattle Fabrics, Inc., Seattle, WA), and fine nylon tulle fabric (Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., Oklahoma, USA), hereafter called mosquito mesh (MM). SS and NN mesh were chosen because preliminary observations indicated they could prevent escape of C. furens (Cooper, unpublished data). Although the MM mesh has openings too large to contain Culicoides, it was included as it has been used successfully in mosquito cage trials28.

Diagram of field cage trials set up aimed to identify a suitable mesh for use in cage field trials. Bioassay cages consisted of cardboard rings and the mesh types: stainless steel mesh (SS), McMaster-Carr, Douglasville, GA, (D) No-see-um netting (NN), Seattle Fabrics, Inc, Seattle, WA., and mosquito mesh (MM) (fine nylon tulle fabric), Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., Oklahoma City. Scale bar inside the cage represents 1 mm.

The mosquitoes-only field cage trial aimed to compare different mesh types for field bioassay cages. Approximately 20 susceptible Ae. aegypti were placed in each cage. After confirming that the mesh types allowed insecticide passage and caused mortality in these mosquitoes, a combined mosquitoes and Culicoides trial was conducted. Each cage contained about 30 field collected C. furens and 20 Ae. aegypti, except for the MM cages, which only had Ae. aegypti (Table 1). This design allowed us to evaluate the susceptibility of field collected C. furens to permethrin relative to susceptible Ae. aegypti.

Cages were hung approximately 1.3 m above ground on shepherd hooks in five clusters, each with the three mesh types (Fig. 1). Clusters were spaced every five meters along a north-south transect, 20 m downwind of the spray truck path (Fig. 1). Two clusters of untreated (control) cages of each mesh type were placed 20 m upwind. Mortality was assessed in the field 10 min post-exposure, and subsequently recorded at 1, 12 and 24 h post-exposure in the laboratory. Mortality was based on knockdown (inability to stand on legs or have coordinated flight15). Insects were provided a cotton round with tap water and maintained in the cages for 24 h, before being placed in dry ice to kill any remaining live insects.

Data analysis

Results from the cage field trials were analyzed by calculating the mean mortality of mosquitoes and Culicoides at various times post-exposure. For each trial, mean mortality and standard deviation were plotted28. For CDC bottle bioassays, time-response survival curves were created for each permethrin dose. Insect survival was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models with the ‘survival’ package in R version 4.2.229. Clustered Cox regression was performed to compare mean mortality across the different permethrin doses for both mosquitoes and Culicoides29, with statistical significance determined at a testing level of 0.05.

Results

CDC bottle bioassays

Susceptible Ae. aegypti reached 100% mortality at 30 min post-exposure in CDC bottle bioassays performed with the high and medium permethrin doses (43 and 21.5 µg /bottle). These same doses caused 100% mortality of C. furens within five minutes post-exposure (Fig. 2). Significantly higher mortality was observed in C. furens exposed to the high dose and medium doses in comparison to mosquitoes (P < 0.0001). The low permethrin dose (10.75 µg /bottle) caused 100% mortality in Ae. aegypti and C. furens at 45 and 30 min, respectively (Fig. 2). No significant difference was observed in the mortality of C. furens and Ae. aegypti exposed to the low dose (P = 0.3699).

The susceptible Ae. aegypti and field collected C. furens did not recover at 24 h with any of the three permethrin doses, with the exception of C. furens from bottles treated with the low dose, in which 5% recovery was observed at 24 h. However, mortality in untreated control bottles was significantly lower in comparison to treated bottles (P < 0.0001). We did not observe significant differences in the mortality of susceptible mosquitoes in comparison to field collected C. furens (P = 1.0000). Abbot’s formula was not used to correct percent mortality in any of the bottle bioassays because control mortality at two hours did not exceed 3%15.

Survivorship of mosquitoes and biting midges in CDC bottle bioassays. Proportion of mortality in field collected Culicoides furens (solid lines) and susceptible Aedes aegypti (dashed lines) exposed to low (10.75 µg / bottle), medium (21.5 µg / bottle), and high (43 µg /bottle) doses of permethrin in CDC bottle bioassays. The vertical dotted line at 30 min denotes the diagnostic time we recommend for C. furens.

Mosquito-only field cage trial

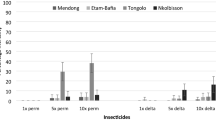

All three mesh types allowed the passage of Permanone 30–30, resulting in mosquito mortality (Fig. 3A). In the mosquito-only trial, two adulticide passes were performed because no mortality was observed within 10 min after the first pass. We were unaware whether the insecticide had not gone through the mesh during the first pass or there was another reason why the insects were not experiencing mortality. A second pass performed within 20 min after the first application resulted in immediate mortality of the exposed mosquitoes.

One-hour post-application, mean mortality rates were 89% (SS), 97% (NN), and 98% (MM) (Fig. 3A). Complete mortality was observed at 12 h in SS and MM cages (Fig. 3A), while NN cages only reached 96% at 12 h, with no further increase by 24 h. Mosquitoes did not recover from the adulticide effects within the 24-hour period. Control cages showed minimal mortality at 24 h, with 15% in MM cages and 5% and 6% in SS and NN, respectively. Since control mortality was only observed after 24 h, Abbot’s formula was not applied to correct the percent mortality in treatment cages15.

Mosquitoes and Culicoides field cage trial

The second trial confirmed that bioassay cages constructed with SS and NN could be used to evaluate Culicoides susceptibility to ULV adulticides. Complete mortality of Ae. aegypti occurred in all bioassay cages within 1-hr post-application (Fig. 3B), while 100% mortality of C. furens was observed within 10 min (Fig. 3C). Mosquitoes and C. furens did not recover from the effect of the adulticide within the 24-hour period. Mortality in untreated control cages was only observed at 24 h for Ae. aegypti placed inside SS cages and biting midges in SS cages (6%) and NN cages (16%). Because 100% mortality was observed in all treatment cages 1-hr post-exposure and no mortality was observed in the control cages until after 24 h post-exposure, Abbot’s formula was not used to correct percent mortality in treatment cages.

Mean mortality and standard deviation of susceptible Aedes aegypti and field collected Culicoides furens at different times post exposure in bioassay cages exposed to ULV applications with Permanone30-30. (A) Mosquitoes only cage field trial (two passes); (B) Mosquito mortality in mosquitoes and Culicoides cage field trial (one pass); (C) C. furens mortality in mosquitoes and Culicoides cage field trial (one pass). Treatments include five cages of each: stainless steel (SS), no-see-um netting (NN), and mosquito mesh (MM).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that both the CDC bottle bioassay and field cage trials can be effectively adapted to assess insecticide susceptibility and efficacy of ULV treatments against Culicoides species. Obtaining this information is advantageous for protecting the health of humans and other animals. Our findings include the first records of DD and DT for Culicoides in CDC bottle bioassays, which can serve as reference for other species, such as C. paraensis, the main vector of OROV. We also identified two suitable mesh types for field cage trials with Culicoides. We observed mortality in C. furens in CDC bottle bioassays using technical grade permethrin and in the field cage trial with Permanone 30–30, which suggests that field populations of C. furens from Indian River County are susceptible to permethrin.

Despite the widespread use of adulticides to control Culicoides, their susceptibility to these treatments remains poorly understood. This study highlights the utility of field cage trials in assessing the effectiveness of adulticide applications against both vector and nuisance species. Although C. furens is not a vector of pathogens, nuisance species can significantly impact the economy. For instance, in Australia, Culicoides nuisance is estimated to reduce residential property values by 8,300 USD per residence based on actual sale price30. Ratnayake and co-authors also suggest that Culicoides prevent urban development in coastal areas, with over half of surveyed residents in Hervey Bay, Australia considering the impact of Culicoides a major factor in housing investment decisions30. Similarly, Culicoides impunctatus Goetghebuer is a nuisance species that impacts the forestry and tourism industries in Scotland and parts of England, causing an estimate of 20% of summer working days lost in the forestry industry due to its nuisance to humans31.

We were able to determine a potential DD and DT using field collected Culicoides. Typically, DD and DT used in CDC bottle bioassays are established using susceptible populations15. Despite numerous attempts to establish Culicoides colonies since 192132, C. sonorensis is the only species colonized in the United States20. Moreover, knowledge about the permethrin susceptibility of C. sonorensis is mainly limited to studies evaluating the impact of permethrin-treated hair clippings on the mortality of biting midges32,33. In the absence of a susceptible Culicoides population for calibration, we adapted the CDC bottle bioassay for field collected C. furens. We found that 10.75 µg permethrin per bottle resulted in 100% mortality of C. furens from Indian River County, FL, within 30 min. Therefore, we recommend using 10.75 µg permethrin per bottle and 30 min as the DD and DT for this and potentially other field collected species of Culicoides. Future studies should consider determining the mean lethal dose (LD50) that is expected to cause death in 50% of treated C. furens.

We expect that the time to reach 100% mortality in CDC bottle bioassays and cage field trials will vary between studies due to various factors. For example, different mortality rates may be observed in cage field trials using different permethrin formulations, even when applied at the same dose. We anticipate that differences in the time to reach 100% mortality in CDC bottle bioassays could occur even within the same species when examining different populations. Although we observed 100% mortality of C. furens from Indian River County, FL within 30 min in CDC bottle bioassays, different results could be observed in tests conducted with C. furens collected in locations where selection pressure is different. This phenomenon has been observed in Culicoides obsoletus Meigen and Culicoides imicola Kieffer, where their country of origin had a significant impact on their susceptibility to deltamethrin and permethrin34.

Culicoides furens from Indian River County, FL, were more susceptible to permethrin than the Ae. aegypti used as a reference for susceptibility in both CDC bottle bioassays and field cage trials. The permethrin DD for Ae. aegypti has been established as 43 µg permethrin per bottle, which is expected to cause 100% mortality at 10 min15.

In our study, C. furens exposed to 43 µg permethrin per bottle were knocked down within seconds after permethrin exposure. Similarly, in our field cage trials, C. furens experienced 100% mortality within 10 min, in comparison to one hour for Ae. aegypti. These disparities in the time to achieving 100% mortality is likely due to the differences in size between the Ae. aegypti from our colony (3.03 mm wing length)35 and the field collected C. furens (0.91 mm wing length)36. The efficacy of ULV insecticide applications against adult mosquitoes is related to the droplet size37. Therefore, application rates on mosquito control product labels are based on the dose needed in a droplet to kill a mosquito based on its size37. In this case, C. furens is a smaller insect and the dose needed to kill it is much lower, resulting in the high mortality we observed in C. furens using a mosquito-specific ULV adulticide application rate.

A delay in mortality after exposure to insecticides may allow infected biting midges to blood feed and potentially transmit pathogens before becoming incapacitated by the insecticide32. This behavior was observed in C. sonorensis exposed to permethrin-treated hair clippings32. However, we cannot confirm whether this behavior would be observed in midges exposed to permethrin through CDC bottle bioassays or field cage trials.

Our results are the first published information comparing SS and NN to perform field cage trials to quantify susceptibility of Culicoides to permethrin adulticide products in the United States. Linley and Jordan18 evaluated the efficacy of thermal fog applications with formulated products contained naled against C. furens. However, the authors highlight that this product was not the most effective compound against Culicoides and that pyrethroid applications including a permethrin formulated product were likely to be more effective16. Complementary studies to these tests, showed that naled applied with a vehicle mounted ULV machine was not effective against C. furens and that this was possibly due to the fine mesh used to confine Culicoides, which did not allow the insecticide to pass through17. Although we found that cages made with SS and NN allowed the passage of ULV permethrin droplets, resulting in C. furens mortality, we recommend using NN since this material is easier to handle and at least 11 times cheaper than SS (NN: USD 5.44/m2; SS: USD 62.20/m2). While our work and that of others18 demonstrate that C. furens is susceptible to adulticides commonly used for mosquito control, it is uncertain whether ULV sprays would be as effective against biting midges in the field. Biting midges are much smaller than mosquitoes, and key behaviors such as resting sites and circadian activity remain poorly understood for most species.

Understanding whether or not Culicoides biting midges are susceptible to the adulticides that are commonly applied for their control provides the opportunity to evaluate current control practices and to potentially replace ineffective methods with more successful, affordable, and sustainable alternatives. We suggest using the methodologies adapted for biting midges in this study for CDC bottle bioassays and field cage trials to evaluate permethrin susceptibility of C. paraensis, the OROV vector. This information will inform whether permethrin applications that may be performed by vector control agencies can also offer protection against the OROV vector. These methodologies could also be used to evaluate insecticide susceptibility in EHDV and BTV vector species on livestock farms. Field collected Culicoides species of medical or veterinary importance could be targeted with ULV permethrin applications, similar to those commonly used for controlling Culicoides on deer farms12. These field-collected Culicoides species. could also be exposed to a CDC bottle bioassay with technical grade permethrin at the DD and DT we suggest (10.75 µg /bottle at 30 min). Although CDC bottle bioassays are generally performed in laboratory settings, the protocol described here is a relatively simple, rapid, and economic test that can be performed in temperature-controlled areas outside the laboratory.

Our results highlight the opportunity of monitoring insecticide resistance as part of an integrated vector management (IVM) program against Culicoides. Effective insecticide resistance management should accompany ULV adulticide applications to ensure long-term control of Culicoides. IVM programs for blood-feeding dipterans often require using multiple control strategies to relieve the biting pressure38. Given the limited alternatives for Culicoides control, effective management relies on accurate susceptibility assessments to ensure that adulticide applications remain effective and to prevent the development of insecticide resistance.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wesselmann, K. et al. Emergence of Oropouche fever in Latin America: A narrative review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24 (7), e439–e452 (2024).

Mohapatra, R., Mishra, S., Satapathy, P., Kandi, V. & Tuglo, L. Surging Oropouche virus (OROV) cases in the Americas: A public health challenge. New. Microbes New. Infect. 59, 101243 (2024).

Moreira, H. et al. Outbreak of Oropouche virus in frontier regions in western Amazon. Microbiol. Spectr. 12 (3), e01629–e01623 (2024).

Huits, R., Waggoner, J. J. & Castilletti, C. New insights into Oropouche: Expanding geographic spread, mortality, vertical transmission, and birth defects. J. Travel Med. 31 (7), taae117 (2024).

Mullen, G. R. & Murphree, S. Biting midges (Ceratopogonidae). In Medical and Veterinary Entomology (eds Mullen, G. & Durden, L.) 213–236 (Academic, San Diego, (2019).

Pfannenstiel, R. S. et al. Management of North American Culicoides biting midges: Current knowledge and research needs. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 15 (6), 374–384 (2015).

Wilson, W. et al. Current status of bluetongue virus in the Americas. Bluetongue 10, 197–220 (2008).

Jiménez-Cabello, L., Utrilla-Trigo, S., Lorenzo, G., Ortego, J. & Calvo-Pinilla, E. Epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus: Current knowledge and emerging perspectives. Microorganisms 11 (5), 1339 (2023).

Yanase, T., Katsunori, M. & Yoko, H. Endemic and emerging arboviruses in domestic ruminants in East Asia. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 168 (2020).

Nkya, T. E., Akhouayri, I., Kisinza, W. & David, J. Impact of environment on mosquito response to pyrethroid insecticides: Facts, evidences and prospects. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43 (4), 407–416 (2013).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Permethrin, resmethrin, d-phenothrin (Sumithrin): Synthetic pyrethroids for mosquito control. (2024). Available at: https://www.epa.gov/mosquitocontrol/permethrin-resmethrin-d-phenothrin-sumithrinr-synthetic-pyrethroids-mosquito-control Accessed on 11 Jan 2024.

Harmon, L. E., Sayler, K. A., Burkett-Cadena, N. D., Wisely, S. & Weeks, E. Management of plant and arthropod pests by deer farmers in Florida. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 11 (1), 12 (2020).

World Health Organization. Monitoring and Managing Insecticide Resistance in Aedes Mosquito Populations: Interim Guidance for Entomologists (WHO, 2016).

Vatandoost, H. et al. Comparison of CDC bottle bioassay with WHO standard method for assessment susceptibility level of malaria vector, Anopheles stephensi to three imagicides. J. Arthropod Borne Dis. 13 (1), 17 (2019).

McAllister, J. & Scott, M. CONUS manual for evaluating insecticide resistance in mosquitoes using the CDC bottle bioassay kit. (2020). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/CONUS-508.pdf Accessed on 11 Jan 2024.

Linley, J. R., Parsons, R. E. & Winner, R. A. Evaluation of naled applied as a thermal fog against Culicoides furens (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 3, 387–391 (1987).

Linley, J. R., Parsons, R. E. & Winner, R. A. Evaluation of ULV naled applied simultaneously against caged adult Aedes taeniorhynchus and Culicoides furens. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 4 (3), 326–332 (1988).

Linley, J. R. & Jordan, S. Effects of ultra-low volume and thermal fog malathion, scourge and naled applied against caged adult Culicoides furens and Culex quinquefasciatus in open and vegetated terrain. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 8, 69–76 (1992).

Kondapaneni, R. et al. Mosquito control priorities in Florida—survey results from Florida mosquito control districts. Pathogens 10, 8: 947 (2021).

McGregor, B., Shults, P. & McDermott, E. A review of the vector status of North American Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) for bluetongue virus, epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus, and other arboviruses of concern. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 9 (4), 130–139 (2022).

McGregor, B. et al. Vector competence of Florida culicoides insignis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) for epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus serotype-2. Viruses 13 (3), 410 (2021).

Buckley, J. J. C. On the development, in Culicoides furens (Poey), of filaria Mansonella Ozzardi Manson. 1897 J. Helminthol.. 12 (2), 99–118 (2009).

Erram, D. & Burkett-Cadena, N. D. Laboratory studies on the oviposition stimuli of Culicoides stellifer (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), a suspected vector of orbiviruses in the United States. Parasites Vectors. 11, 300 (2018).

Zhu, Q. et al. Photodegradation kinetics, mechanism and aquatic toxicity of deltamethrin, permethrin and dihaloacetylated heterocyclic pyrethroids. Sci. Total Environ. 749, 142106 (2020).

Brogdon, W. & Chan, A. Guideline for evaluating insecticide resistance in vectors using the CDC bottle bioassay with inserts 1 (2012) and 2 (2014). CDC Technical Report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/features/bioassay.html. Accessed on 11 Jan 2024.

Parker, C. Collection and rearing of container mosquitoes and a 24-h addition to the CDC bottle bioassay. J. Insect Sci. 20 (6), 13 (2020).

Kim, D., Burkett-Cadena, N. D. & Reeves, L. E. Pollinator biological traits and ecological interactions mediate the impacts of mosquito-targeting malathion application. Sci. Rep. 12, 17039 (2022).

Buckner, E. A. et al. An evaluation of 6 ground ULV adulticides against local populations of Aedes taeniorhynchus and ae. Aegypti in Manatee County, FL. Wing Beats. 27, 17–19 (2016).

Burgess, E. R. et al. Assessing pyrethroid resistance status in the Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae) from the northwest suburbs of Chicago, Illinois using Cox regression of bottle bioassays and other detection tools. PLoS ONE. 17, e0268205 (2022).

Ratnayake, R. et al. Evaluation of integrated pest management practices for vector control in Sri Lanka. Trop. Med. Health. 34, 24–32 (2006).

Hendry, G. & Godwin, G. Biting midges in Scottish forestry: A costly irritation or a trivial nuisance? Scott. Forestry. 42, 113–119 (1988).

Mullens, B. A., Velten, R. K., Gerry, A. C., Braverman, Y. & Endris, R. G. Feeding and survival of Culicoides Sonorensis on cattle treated with permethrin or pirimiphos-methyl. Med. Vet. Entomol. 14 (3), 313–320 (2000).

Mullens, B. A. In vitro assay for permethrin persistence and interference with blood feeding of Culicoides (DIptera: Ceratopogonidae) on animals. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 3, 256–259 (1993).

Del Rio, R. et al. How do species, population and active ingredient influence insecticide susceptibility in Culicoides biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) of veterinary importance? Parasites Vectors. 8, 439 (2015).

Aldridge, R. L. et al. Lethal and sublethal concentrations of formulated larvicides against susceptible Aedes aegypti. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 38, 250–260 (2022).

Blanton, F. S., Wirth, W. W. & Division of Plant Industry. The sandflies (Culicoides) of Florida. Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services,. (1979). Available at: http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00000090/0000 Accessed on 11 Jan 2024.

Mount, G. A. A critical review of ultralow-volume aerosols of insecticide applied with vehicle-mounted generators for adult mosquito control. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 14 (3), 305–334 (1998).

Beier, J. C. et al. Integrated vector management for malaria control. Malar. J. 7, 1–10 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah McInnis, Victor Recendez, Heather Whitehead (Indian River County Mosquito Control District), and Morgan Rockwell (UF/IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory) for their support during field cage trials. We thank Ana Romero-Weaver for training VMC in CDC bottle bioassays and Tanise Stenn for rearing mosquitoes used in this study. Funding for this work was provided by the Florida State Legislature, through the Cervidae Health Research Initiative and NIFA Project FLA-FME-006106.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C., N.B.C, and E.B. designed the experiments. Y.J coordinated and provided resources for field trials. V.C., N.B.C, and E.B carried out the experiments and conducted the data analysis. V.C wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and provided feedback for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, V.M., Buckner, E.A., Jiang, Y. et al. Laboratory and field assays indicate that a widespread no-see-um, Culicoides furens (Poey) is susceptible to permethrin. Sci Rep 15, 4698 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89520-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89520-0