Abstract

In the last decades, the availability of multi-source, multi-scale, and multi-resolution remote sensing data and the consequent progress of processing techniques brought a significant positive impact for landslide detection. As a result, nowadays also public institutions dealing with geo-hazard management worldwide regularly use satellite data and products in landslide investigations. Due to the complexity of the phenomenon which might involve the displacement of massive rocks, soil, and both wet and dry vegetation from hillslopes, and the significant impact on the safety of the population and road infrastructure, the development of specific procedures for the rapid detection of landslides is extremely challenging. This is particularly important in the first phases of landslide risk management to evaluate the extension of the area involved by the movement and proceed with an initial delimitation of the so-called alarm zone, where preventive evacuation must be applied. In this study, the wide-ranging Tasseled Cap Transformation (TCT) is proposed as a not-sophisticated and rapid method able to detect different land-change features simultaneously by processing only two (pre- and post-event) Sentinel-2 images. The RGB color composite image obtained by stacking δTCTBrightness, δTCTGreenness, and δTCTWetness, as the intensity of red (R), green (G) and blue (B) was able to provide information on landscape changes supported by the physical nature of the TCT indices, by associating the colors to the physical characteristics of the changes. The method tested over the Pomarico site in Basilicata region (Southern Italy), was able to define the footprint of a landslide occurred in 2019 with a good accuracy (ACC = 0.95). Therefore, the proposed procedure is effective to detect landslides involving land-surface spectral changes (the majority), without the need of additional in-situ information. Furthermore, the free availability of the Sentinel-2 database and its frequent revisit times guarantee its global exportability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides are major hazards in hilly and mountain landscapes1, causing hundreds of deaths and injuries everywhere in the world, population displacement, and detrimental impacts on the environment with consequent billions of dollars in financial losses each year that, often, result in long-term economic upheaval2. They are complex phenomena characterized by extreme spatial, temporal and speed variability3, whose study requires the application of a multidisciplinary approach based on the integration of different investigation methods4,5,6,7. In recent years, specific satellite, airborne and in situ techniques have been proposed as essential components of landslide early warning systems8.

The development of appropriate technologies based on low-cost systems and wireless sensor networks9,10 and the free availability of images acquired by remote sensing (RS) sensors contribute to provide an increasing amount of information about the superficial and deep characteristics of the slope affected by a landslide.

The surface characterization and rapid identification of the landslide body can be considered the most important information to obtain in emergency scenarios. Indeed, they can suggest to the civil protection authorities the area where applied preventive evacuation and rapid actions to be taken to secure the population as well as contribute to the designing and deploying of effective monitoring systems11,12.

Accurate information on landslide areas can be obtained from high-quality geomorphological inventories. High-quality landslide maps, for example, can be realized using in situ measurements and field surveying but they are time-consuming, expensive, and difficult for local to global scales13 and references herein). In many areas, given the unavailability of such information and the local settings, it may be difficult to adopt these approaches.

In the last years, RS has shown to be an efficient technique to provide information for landslide studies without physical contact with the environment13. Alternatively, Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) also provide an easy-to-use tool for the description, at very high resolution, of different type of environmental phenomena or natural hazard14. Among others, the landslide mapping has been one of the most frequent type of applications15,16,17.

As shown by numerous review papers18,19,20,21, an extensive bibliography concerning the application of RS techniques to landslide study is available indicating that both radar22 and optical satellite data23,24,25,26 allow for rapid and easily updatable data acquisitions, improving the traditional capabilities of detection, mapping and monitoring, and optimizing the fieldwork also in hazardous or inaccessible areas20.

According to18, landslide mapping using optical imagery can be conducted through: (i) visual interpretation27; (ii) pixel-based classification28,29 and (iii) object-oriented methods30,31,32; (iv) change detection techniques33,34,35; and (v) image correlation36,37,38.

Among the aforementioned techniques, the change detection based on spectral information is the most commonly used as it allows for easy identification of landslides by comparing satellite images taken before and after an event39 and references herein. Instead, an updated list of pixel-based and object-oriented methods developed for mapping landslide from RS optical images can be found in40. For both the above-mentioned analysis, machine learning (ML) methods (such as random forests, support vector machine, and logistic regression) have been extensively used to identify landslides41.

In the field of optical imagery, since 2000 commercial very high-resolution satellites have proven to be a powerful tool for rapidly producing regional and local landslide maps32,42,43.

Recently, high-resolution Sentinel-2 MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) data, openly and freely accessible to all users worldwide, have been largely used for landslide detection. For instance, the United Nations Satellite Centre (UNOSAT), which is part of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), inserted Sentinel-2 imagery in its data source portfolios to support UN agencies and the member states with a Geospatial Analysis Service to tackle disasters and complex emergencies (https://unosat.org/products/). In fact, Sentinel-2 data represent a good trade-off between image footprint size, coverage and spatial and spectral resolution for emergency mapping thanks to its frequent return interval (5 days at the equator and 2–3 days at mid-latitudes by combining Sentinel-2 A and Sentinel-2B orbits) that increases the availability of pre- and post- event imagery close to the occurrence date44.

Most efforts in this field of research have been focused on producing and selecting landslide features by using Sentinel-2 data, mainly including spectral bands45 or spectral derivatives of the images, such as spectral indices39,40,46,47,48 or geophysical layers such as Digital Elevation Model (DEM)49,50,51,52. The use of vegetation indices is one of the most common approaches adopted to detect landslide; in particular, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is the most popular vegetation index, broadly used for landslide detection because is less sensitive to topographic effect and, therefore, suitable to be applied also over mountainous areas53,54,55. However, the use of NDVI is limited to areas exclusively covered by vegetation cover change, whereas landslides can also move massive rocks and soil from hillslopes. To overcome this limit, in this study we used the Tasseled Cap Transformation56, which can be applied in change detection analyses involving different land features simultaneously. The TCT has been successfully adopted in many research fields and with different satellite data57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65.

As for landslide detection, some studies have used this method for analysing satellite data with the support of additional information or auxiliary datasets66,67,68,69,70. The TCT-based approach to landslide detection proposed in this paper, instead, uses just two (pre- and post- event) Sentinel-2 images to single out changes. Thanks to the availability of TCT coefficients specifically addressed for Sentinel-2 data, the method enables the concurrent identification of specific changes in soil, vegetation, and near-surface water associated with landslide events. Unlike single-index methods like NDVI or basic threshold-based techniques, TCT offers a multi-dimensional perspective that effectively captures complex spectral changes as those induced in landslide-impacted areas. It also delivers robust results while being less computationally demanding than supervised classification methods, making it particularly useful in regions with limited training data availability.The relative simplicity and parsimony of the method and the use of free multispectral satellite images make this approach very appealing due to the need of rapid response to landslide events and the demand of accurate monitoring of landslide evolution. Especially in areas at high hydrogeological risk, detection and monitoring strategies that do not require sophisticated algorithms, expensive datasets, and the involvement of highly skilled technicians are strongly advisable.

Our method was applied to a landslide occurred on 29 January 2019 within the municipality of Pomarico (Matera - Italy) in an area vulnerable to erosion due to its geological, geomorphological and hydrogeological settings71,72. This landslide caused the collapse of the main road of the town and overlooking buildings73,74. Both vegetated and bare/impervious soils were involved in the failure making this landslide a good study case to test our TCT-based approach. In addition, the availability of data from an UAS-derived orthomosaic (at 10 cm of resolution) and other support information enabled us a careful high-resolution validation of the final landslide map.

Study area

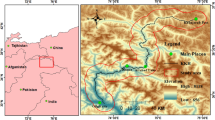

Pomarico is a small municipality of Basilicata (Southern Italy; Fig. 1) characterized by a prevalence of agricultural crops (mainly olives groves) and natural covers (i.e., shrublands) bordering the industrial area of Val Basento, founded in Fifties after the discovery of a large methane deposit and hosting mainly chemical industries75. It is located in the southern-eastern part of the Bradanic Trough, a structural depression between the Apennines Chain and the Apulian Foreland, that is filled up by Plio-Pleistocenic deposits.

The peculiar geological, geomorphological, hydrogeological and climatic features (driest periods are contextual with the hottest periods of the year, see76 of this area make it very prone to erosional processes and landslide occurrence77.

(source: Google Map Satelllite imagery available in QGIS software); (b) the red star identifies the Pomarico municipality in the Basilicata (Southern Italy); (c) orthophoto 2020 of the Pomarico municipality (https://rsdi.regione.basilicata.it/) with landslides of IFFI (Inventario dei Fenomeni Franosi in Italia) Project 2020 overimposed (http://www.progettoiffi.isprambiente.it/cartanetiffi/; accessed on September 2023); (d) zoom of the orthophoto 2020 of the study area and (e) the corresponding geological map by Perrone et al. 2021. Maps created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/.

Location of the Pomarico landslide (centered in 40° 30’ 53,08’’N 16°33’ 00,13’’ E, UTM/WGS84 projection): (a) the red square identifies the extent of the downloaded satellite images.

The village is located on the hilltop of a narrow ridge (oriented NW-SE) where coarsening upward deposits outcrop, as results of a regressive depositional environment. The deposits at the bottom belong to the Sub-Apennine Clays Formation passing upward to the layered sandy deposits of Montemarano Formation. The Sub-Apennine Clays Formation consists of marly clays, clays, and silty clays, interbedded with silty and sandy levels78 whose frequency and thickness increases upwards72, until they become prevalent, the stratigraphic contact to the overlaying Montemarano Formation is clearly identifiable along the slopes of the Pomarico hill78. The Montemarano Formation consists of yellows sands, scarcely cemented, interbedded with silty clay (especially in the lower part of the formation) and arenaceous horizons, with a maximum outcropping thickness of 50 m.

The sides of the ridge are steep and particularly exposed to landslides: mainly composite, retrogressive, translational-rotational slide. In the southwestern slope, scarps, counter-slope and morphological depressions deriving from old landslides can be distinguished (IFFI-Inventario dei Fenomeni Franosi in Italia- Project by ISPRA, Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo, Servizio Geologico d’Italia. Available online: http://www.progettoiffi.isprambiente.it/cartanetiffi/ ). Along the whole slope is present a sandy-clayey debris in which blocks of the arenaceous layers are incorporated.

The latest main landslide started as earth-flow on 25th of January 2019, on the northern east side of the hill, rapidly evolving as roto-translational slide on January 29th, causing the collapse of the main road of the town as well as of the overlooked buildings and serious damages of several buildings of the town73.

Data

Satellite images

From the Sentinel Scientific Data Hub (https://scihub.copernicus.eu/), we downloaded two Sentinel-2 Level-1 C scenes (tile 33TXE of the Sentinel-2 tile system) cloud-free at least for the landslide site. In particular, pre- and post-event images acquired at 9:43:19 UTC on January 20, 2019 and on February 9, 2019, respectively (UTM/WGS84 projection) were used. The multi-temporal registration performance between the adopted products is better than 0.3 pixels79.

Sentinel-2 satellite is a multispectral Earth observation system of the Copernicus Earth Observation programme of the European Union. At the moment, this system includes two polar-orbiting satellites (i.e., Sentinel-2 A and Sentinel-2B) having the same orbit but phased at 180° to each other. Together, the two satellites have a high revisit time of 5 days at the equator, 2–3 days at mid-latitudes. The satellites carry the Multi Spectral Instrument (MSI) that samples 13 spectral bands (with a spatial resolution from 10 m to 60 m) from visible and near-infrared (VNIR) bands to short wave infrared bands (SWIR). Table 1resumes the Sentinel-2 main features. Level-1 C (Top of Atmosphere – ToA) and Level-2 A (Bottom of Atmosphere – BoA) product levels are freely available to users to meet different needs and to improve numerous operational applications such as land monitoring service80,81, emergency management82, risk mapping83, etc.

Unmanned aircraft system (UAS) data

The UAS survey was performed with a DJI Phantom 4 Pro quadcopter (DJI, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a gimbaled 1-inch 20-megapixel CMOS sensor with a mechanical shutter. Given the good illumination conditions, the camera sensitivity was set to ISO100 for all images, with an aperture F/2.8 and the shutter time of 1/1250 sec. All images were georeferenced with the on-board GPS.

The mission planning was executed in Pix4Dcapture using a side overlap of 60% and a front overlap of 80%.

Flight mission was performed on January 31th, 2019, six days after the landslide event, between 11:00 a.m. and 12:50 UTC. The flight was performed using a horizontal flight plan at 100 m about the take of point that was located at the elevation of 420 m a.s.l. Given the local orography, the resolution of the ground sampling distance (GSD) was between 2,74 cm/px and 6.85 cm/px. The orthomosaic was generated with a final spatial resolution of 10 cm/px.

The collected imagery has provided useful guidance for the preliminary emergency activities of the Civil Protection and Firefighters. Survey was used to analyze the impact of the event on the urban settlement of Pomarico, also deriving a 3D model of the entire landslide exploiting the software Agisoft Metashape v.2.0.0. The model was obtained from a dense cloud with 66,657,789 points.

Methods

Detection

Most landslides cause land changes involving bare soil, impervious areas, vegetation, and water in the near surface. These land changes occur mainly in presence of particularly fast earth, mud or debris flows that have the capacity to significantly reshape the slope morphology and characteristics, by re-working the material, eradicating the vegetation on the slope, creating counter-slope areas where a greater water content can occur, so modifying the spectral characteristics of the slope involved in the movement. The rationale behind our approach is that we can use validated spectral methods, able to effectively pick up relevant land characteristics in multi-spectral images, to design a change detection procedure to identify the areas involved in a landslide.

In this study, the pre-event (20 January 2019) and post-event (9 February 2019) Sentinel-2 images were used to detect landslide-driven changes. We applied the Tasseled Cap Transformation (TCT) technique, an orthogonal spectral feature space transformation originally derived for Landsat data56,84. It combines information from multiple bands (ToA values) using sensor-specific coefficients85 to create the essential components of a landscape: (i) TCT’s first component, an index of the overall Brightness of the image; (ii) TCT’s second component, an index of the Greenness; (iii) TCT’s third component, an index of Wetness. The rest of the bands does not contain significant information and can be considered as noise in the application concerned.

Therefore, the first three components have been frequently used as a proxy for measuring these biophysical parameters86 and references herein).

The TCT Brightness, Wetness and Greenness indices were produced for the pre-event and post-event satellite images by using the following equation:

where B2, B3, B4, B8, B10, B11, and B12 are the Sentinel-2 bands (see Table 2) while the letters from A to G are the TCT coefficients suggested by the Index Data Base for Sentinel-2 sensor (https://www.indexdatabase.de).

Because Sentinel-2 data are a multi-size product (Table 1), all the pre-event and post-event bands at 20 m (i.e., S2_B11 and S2_B12) included in the formula (1) were upsampled to 10 m resolution using the nearest neighbor method before to apply TCT.

To show the change between the pre and post event, image differencing was done using the TCTindices according to the following formula:

Then, an RGB composition was produced using \(\:\delta\:\)TCTBrightness (\(\:\delta\:B\) hereafter), \(\:\delta\:\)TCTGreeness (\(\:\delta\:G\) hereafter), and \(\:\delta\:\)TCTWetness (\(\:\delta\:W\) hereafter) as the intensity of red (R), green (G) and blue (B) respectively.

The composite image enabled the synthesis of the land-cover changes due to the landslide observed on three bands in a single image. In the RGB composite image, an evident chromatic anomaly emerges in correspondence to the landslide scar. This anomaly appears as a well-defined cluster and a good candidate to be labelled as landslide.

To detect the landslide, a manual visual method has been applied being this a good recognized solution to easily account for spatial information, especially when the intensity contrast between different surface features is very high49,87.

Moreover, an RGB color wheel showing all combinations of increasing and decreasing \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{index}\) was performed as a legend highlighting the interpretation of the major types of landscape changes.

Finally, a binary map was segmented by setting to one all the foreground pixels (i.e., pixels with high intensity changes with respect to the background in the derived RGB composite image) and to zero values all the remaining pixels.

Performance evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the procedure, the derived satellite binary map was compared with the visual reference map produced by manually digitizing the landslide scar on the UAS orthophoto. For the visual interpretation, a geomorphological map, obtained as result of in situ geomorphological surveys, analysis of inventory mapping data (Inventory of Landslide Phenomena in Italy, IFFI Project 2020 and previous studies78 and reference therein), has also been used.

The final product was another binary map segmented by setting to zero value all the pixels with no change and to one all pixels with changes. Both the binary maps were resampled at 10 cm (i.e., the orthophoto spatial resolution), then they were overlaid and each pixel was labelled according to four possible entries: true positive (TP) for pixels correctly classified as landslide, true negative (TN) for pixels correctly classified as not landslide, false negative (FN) for undetected landslide areas, false positive (FP) for areas erroneously classified as landslide. Several statistical rates based on these four outcomes have been computed to determine the performance of the classification, including the True positive rate (RTP), False negative rate (RFN), True negative rate (RTN), False positive rate (RFP), Accuracy (ACC), Precision or Positive Predictive Value (PPV), F-score and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). This last one is considered as a more informative and reliable metric, especially for imbalanced classes, since it produces a high score only if the prediction obtains good results in all of the four confusion matrix categories88.

The flowchart of the developed method is shown in Fig. 2.

Scheme of the procedure of the developed landslide detection method. The image represents the UAS orthophoto image of the study area (QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/).

Furthermore, polygons were manually drawn on the orthoimage to identify the benchmarking map subtypes and support the correct interpretation of the changes occurred.

Results

Figure 3 displays the Sentinel-2 A image collected before (20th January 2019, Fig. 3a) and after the event (9th February 2019, Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows the result obtained by applying formula (2), i.e., the difference between the TCT applied after and before the event on the Sentinel-2 images.

(source: https://scihub.copernicus.eu/); (c) RGB composition with R=\(\:\delta\:\)TCTBrightness(\(\:\delta\:B\)), G= \(\:\delta\:\)TCTGreeness (\(\:\delta\:G\)), and B= \(\:\delta\:\)TCTWetness (\(\:\delta\:W)\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}\text{p}\text{e}\text{c}\text{t}\text{i}\text{v}\text{e}\text{l}\text{y}\). Maps created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/.

Natural composite of Sentinel-2 image (a) before the event and (b) after the event.

The RGB composition was produced using \(\:\delta\:B\), \(\:\delta\:G\), and \(\:\delta\:W\) as the intensity of red (R), green (G) and blue (B) channels respectively. Evidence of land changes due to the landslide appears clearly as a well-defined cluster colored in magenta and red. The \(\:{TCT}_{index}\) and \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{index}\) single maps are not reported for the sake of brevity.

Figure 4a resumes the main RGB color combinations and the corresponding behaviour of the associated \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{index}\) combination; each \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{index}\) is characterized by direction and magnitude of spectral changes. The wheel color logic helped to interpret the landscape changes and to correctly define the landslide footprint. In fact, a post- and pre-event landslide change detection is characterized mainly by strong variations in the size of bare soil (increasing) and vegetated areas (decreasing). Therefore, pixels showing an increase in \(\:\delta\:B\) and decrease in \(\:\delta\:G\) were identified as belonging to the landslide (indicated by the magenta and red colors of the wheel).

Moreover, the magenta colors indicate high \(\:{\updelta\:}\text{W}\) values, whereas the red region low \(\:{\updelta\:}\text{W}\) values. The \(\:\delta\:W\) values seem to increase inside the landslide body and decrease along its borders. The high \(\:{\updelta\:}\text{W}\) values were associated with the core of the active earthflow and can be justified both by the geomorphologic setting of the slope after the event and by the hydrological characteristics of the material involved in the movement.

The presence of counter slopes within the active earth-flow may have favored the superficial accumulation of rainwater. This latter was not able to infiltrate a soil already characterized by a high-water content. Indeed, it is well known that the landslide was triggered by a phenomenon of prolonged rainfall78 which led to soil saturation. It is therefore reasonable to assume that at the date of the second Sentinel-2 image used, the reworked landslide material still had a high-water content also favored by the presence of clayey lens. The low \(\:{\updelta\:}\text{W}\) values are localized along the landslide borders, characterized by drier and unvegetated areas, where rainwater was more easily drained.

A comparison with the UAS image and the geomorphological map of the slope by Perrone et al., 2021 confirmed these assumptions.

Figures 3c and 4b clearly show the chromatic gradient between the magenta/red pixels internal to the landslide and the more stable surroundings.

Small clusters of black pixels, located in proximity to magenta and red pixels on the northeastern and southwestern sides, were excluded from the landslide detection due to their minimal decrease in \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{indeces}\) (very close to zero) indicating no-change pixels. In effect, the analysis of very high spatial resolution images available in Google Earth shows the presence of bare soil in such an area already before the event. This means that if a change occurred in this area, it might be produced only by the accumulation material but neither coverage nor moisture content have deeply changed.

Instead, pixels colored in blue correspond to highest \(\:{\updelta\:}\text{W}\) values, i.e., to a very small pool as shown in the UAS image (see orthophoto image of Fig. 2), produced by the damming of the Pezzillo stream due to the accumulation material as described in Perrone et al., 2021 (Fig. 4c).

(a) RGB color wheel showing all combinations of increasing and decreasing \(\:{\delta\:TCT}_{index}\:\); (b) result of the proposed method with the derived landslide scar (in yellow); (c) geomorphological map by Perrone et al. 2021. Maps created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/.

As Fig. 4b shows, the stream is located just outside the landslide boundary, into a depressed area on the southwestern side of the landslide foot between the 220 m and 240 m contour lines (Fig. 5). Very dark blue color pixels, located inside such an area and showing δW values lower than the surrounding pixels, indicate the presence of water already in January 2019 and a successively increase of water level in February 2019.

Result of the proposed method and contour lines derived from the UAS - Digital Elevation Model (DEM). Map created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/.

Figure 6 shows the benchmark map resulting from the comparison between the scar obtained by the application of the TCT on the Sentinel-2 images and the shape of the landslide derived from the UAS-derived orthophoto. Green, black, red, and white polygons represent True Positive (landslide correctly identified), False Negative (true landslides that is omitted by our method), False Positive (non-landslide areas, falsely detected as landslides by our method), and True Negative (true non-landslide that was correctly classified) pixels respectively.

(c) Contingency map of the study area by comparing (b) the reference landslide map (produced manually by experts through UAS visual interpretation) and (a) the landslide area identified using Tasseled Cap Transformation (TCT). Green, black and red colours indicate agreement, underestimation and overestimation, respectively. Maps created with The MathWorks Inc. (2022); MATLAB version R2022b, Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc. https://www.mathworks.com.

Table 3 reports the values of the four entries of the contingency table, while Table 4 provides the performance measures derived from these values. The adopted method shows an accuracy of 95% (ACC = 0.95) with the F1_score and MCC values of 0.83 and 0.80 respectively. The 79% (RTP) of the pixels are correctly identified as landslide. The underestimated landslide area (number of FN pixels) is larger than the overestimated landslide area (number of FP pixels) as Table 3 shows, with a RFN and RFP of 21% and 2% respectively (Table 4).

The comparison between the benchmarking map (Fig. 6c) and the UAS orthophoto shows that the majority of misclassified areas are located at the edges of the landslide or in their immediate surroundings. When the landslide boundary intersects a Sentinel-2 pixel, the pixel is split into two parts (landslide/non-landslide) and cannot be correctly labeled in its entirety, resulting in the misclassification of a portion of the pixel. The loss of accuracy determined by this problem is exclusively due to the sensor resolution and does not depend on the methodological approach. As regards the areas within the landslide boundaries buffer, mislabeled pixels exhibit complex features (texture, cover, morphology, etc.) and show less evident signs of change that are more difficult to be identified (e.g., vegetation is only partially removed).

The underestimated pixels mainly occurred on the uppermost and western parts of the landslide. After a thorough analysis conducted by a geologist who used an UAS orthoimage to assist in identifying feature subtypes, it was discovered that these pixels are mainly characterized by the presence of residual vegetation, i.e., medium and high vegetation destroyed by the mass movement (~ 13%), clay (~ 4%), construction/demolition waste (~ 6%), and shaded areas (~ 17%). In particular, as Fig. 7 shows, pixels showing construction/demolition waste are in the upper part of the landslide due to the destruction of the main road and the evident loss of numerous houses and main urban infrastructures (see Perrone et al., 2021). Instead, shadows are mainly concentrated along the northeast side of the landslide, close to a densely high-vegetation area. Finally, vegetation and clay soil are distributed mostly in the southwestern part of the landslide (in proximity of the foot of the landslide body).

Results of the examination of the contingency map (under false negative-FN pixels) areas trained by a geologist expert using a UAS-based orthomosaic as guidance for the identification of features subtypes. (Maps created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/).

Results of the examination of the contingency map (under false positive-FP pixels) areas trained by a geologist expert using a UAS-based orthomosaic as guidance for the identification of features subtypes. (Maps created in QGIS3.22.16, https://www.qgis.org/.).

On the whole, as Fig. 8 shows, the overestimated pixels occurred on the lowermost and eastern side of the landslide and are mainly composed of a mix of clay soil (~ 16%), vegetation (~ 34%), and shadows (~ 25%). Moreover, within FP pixels also badlands, which characterize the study area, are included along the border of the south-eastern side of the landslide as shown in the pictures 6 and 7 of Fig. 7. This error is probably due to the brightness of the clayey slopes.

Discussion

We evaluated the accuracy of our approach and compared it to other recently published studies which also used algorithms for extracting landslide scars from Sentinel-2 data and employed very high spatial resolution imagery for validation, as we did in our own analysis54,55. Our results (ACC = 0.95 with the F1_score = 0.83 and MCC = 0.80) are in line with their results (Qu ei al., 2021 with a user’s accuracy = 95.38% and a producer’s accuracy = 91.21%) or show a more accurate performance (user’s accuracy = 90.8% and producer’s accuracy = 74.9% for the 2018 year for54.

Unlike these works, which focused just on the detection of vegetation disturbances, our method estimates simultaneously land changes involving bare soil, impervious areas, vegetation, and water in the near surface that result in changes in Brightness, Greenness and Wetness suitable to detect displacement from hillslopes involving rocks, soil, and both wet and dry vegetation. This interpretation of changes is aided by the physical nature of the TCT indices which allow colors in the composite image to be related to physical characteristics of the changes87.

Moreover, our procedure does not require the selection of a threshold for the landslide scar extraction that, as known, is a problem far from trivial.

If the soil types surrounding the landslide are composed by soil material with reflectance values similar to the ones of the landslide, the performance of our approach may be limited. This is the case, in our study, of the presence of the clay slopes and badlands located at the border of the landslide and consisting in the same lithology of the main landslide body. In fact, although it was stable, showed the same values of brightness of the landslide, making its scars larger. Generally, this is a typical commission error occurring on the borders. Instead, an omission error might occur if the soil material is collected in an area already occupied with the same material, by creating an accumulation.

Moreover, errors can derive from the presence of vegetation. In fact, sometimes rests of vegetation (trees and bushes involved in the gravitational phenomena) destroyed by the landslide moved replacing some areas of the landslide scars. If they occur within pixels adjacent to vegetation pixels (such as, for example, woods) an omission error occurs, and the landslide scar is smaller as our case study showed.

As optical satellite images, Sentinel-2 data are significantly influenced by the presence of clouds and shadows89,90 that, as our work revealed, can affect the results. To overcome these limits, the acquisition of available optical data free of clouds in the areas of interest and collected when the sun is at its azimuth is recommended. On the contrary, a de-shadowing method91,92,93 may be applied in the image pre-processing.

Finally, the metrics adopted for evaluating the performance of our method were also affected by the uncertainty due to the manual delineation by visual interpretation that, even if performed by an expert, depends on various factors, that can be subjective, non-repeatable and cannot constitute a completely true reference. Nevertheless, the visual interpretation represents the most common method for the detection of landslides based on optical RS data26,94,95 and, when a valid ground truth reference dataset is not available, it remains the only reliable reference data. Therefore, if some of the disagreements between the two compared datasets can be attributed to the uncertainty in the manual delineation, the accuracy of the applied method may be larger than the calculated values. At least they would fall in the same range of acceptable uncertainty that commonly used manual delineations suggest. Of course, this could only be confirmed if a valid ground truth reference dataset was available that also allows the accuracy of the manual delineation to be assessed49.

Finally, Sentinel-2 images confirm to have a great potential for the rapid detection of landslides, especially earthflow and roto-translational slides, occurring after intense rainfall events and altering ground surface characteristics quickly. In particular, our method offers the possibility to:

-

use Sentinel-2 images to detect the occurrence of the landslide and estimate the time in which the movements began (only for landslides formed after the launch of Sentinel-2 in June 2015);

-

determine intermonth variation thanks to the Sentinel-2 frequency and define patterns of stabilization;

-

quantify the duration of active and stable landslide phases;

-

assess patterns of vegetation recovery.

The main limits of the method are:

-

the presence of clouds in the Sentinel-2 images;

-

presence of soil showing same values of reflectance of the landslide;

-

the pixel resolution (10 m x10m for Sentinel-2) which allows only the detection of landslide larger than about 2-by-2 Sentinel-2 pixels (10 m), the equivalent of 0.04 ha.

Conclusion

This work aims to provide a fast landslide detection during the post-disaster assessment.

Our results confirmed that Sentinel-2 is suitable for landslide mapping: using only two 10 m spatial resolution Sentinel-2 images (pre- and post- event), the footprint of the landslide occurred over the Pomarico site on January 2019 was detected with a good accuracy by applying the Tasseled Cap Transformation (TCT), a simple but effective method suitable to identify land-change in soil background reflectance, vigour of green vegetation, and surface moisture content simultaneously. In particular, the RGB color composite image obtained by stacking its three derived primary and more significant components, i.e., δTCTBrightness, δTCTGreenness, and δTCTWetness, as the intensity of red (R), green (G) and blue (B), supported by the physical nature of the TCT indices, enabled the synthesis of the landscape changes showing the landslide as an evident chromatic anomaly and a well-defined cluster.

The innovation of this approach stems from its ability to simplify complex spectral data into concise, meaningful indices that highlight critical land cover changes. Its seamless integration with Sentinel-2 data amplifies its effectiveness, leveraging the sensor’s spectral range and fine spatial detail to analyze large regions with precision and reliability. These strengths collectively make TCT a valuable tool for large-scale monitoring, enabling accurate and timely identification of landslides, even in challenging or data-scarce environments, with the only obvious exception of landslides that do not induce any spectral alteration of the surface. This could occur in the presence of really very slow landslides, such as the deep-seated gravitational slide, or when the movement is caused by the fracturing in competent rocks without the following reworking of the material. However, these are types of landslides that occur at a very low percentage and which often do not expose to a high risk. For all the remaining ones, which constitute the majority on Italian territory, the proposed approach can be considered extremely effective.

The primary benefit of such a procedure is its capacity to run speedy, due in part to the TCT, a basic tool integrated into the main image processing software, easy to apply even for non-experts who may lack experience with complex techniques like machine learning or methods requiring ground truth data, such as supervised classification, which are often used for landslide identification; secondary, the use of free and easily accessible satellite data with a high revisit frequency (5 days at the equator, 2–3 days at mid-latitudes). If the planned launch of the Sentinel 2 C and Sentinel 2D satellites will proceed as programmed, this dataset will become even more appealing to governmental agencies tasked with addressing landslide disasters and other complex emergencies worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Novellino, A. et al. Mapping landslides from space: A review. Landslides 21, 1041–1052 (2024).

Highland, L. & Bobrowsky, P. The Landslide Handbook—A Guide to Understanding Landslides 129 (2008).

Cruden, D. M. The first classification of landslides? Environ. Eng. Geosci. 9, 197–200 (2003).

Perrone, A. et al. Joint analysis of SAR interferometry and electrical resistivity tomography surveys for investigating ground deformation: The case-study of Satriano Di Lucania (Potenza, Italy). Eng. Geol. 88, 260–273 (2006).

de Bari, C., Lapenna, V., Perrone, A., Puglisi, C. & Sdao, F. Digital photogrammetric analysis and electrical resistivity tomography for investigating the Picerno landslide (Basilicata region, southern Italy). Geomorphology 133, 34–46 (2011).

Bentivenga, M. et al. Geomorphological and geophysical surveys with InSAR analysis applied to the Picerno earth flow (southern Apennines, Italy). Landslides 18, 471–483 (2021).

Frodella, W. et al. Integrated approach for landslide hazard assessment in the high city of Antananarivo, Madagascar (UNESCO tentative site). Landslides 19, 2685–2709 (2022).

Segoni, S., Piciullo, L. & Gariano, S. L. Preface: Landslide early warning systems: Monitoring systems, rainfall thresholds, warning models, performance evaluation and risk perception. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 3179–3186 (2018).

Chu, M. et al. SitkaNet: A low-cost, distributed sensor network for landslide monitoring and study. HardwareX 9, e00191 (2021). SitkaNet.

Bagwari, S., Gehlot, A., Singh, R., Priyadarshi, N. & Khan, B. Low-cost sensor-based and LoRaWAN opportunities for landslide monitoring systems on IoT platform: A review. IEEE Access 10, 7107–7127 (2022).

Scaioni, M. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: From research into practice. Remote Sens. 5, 5488–5492 (2013).

Manconi, A. et al. Brief communication: Rapid mapping of landslide events: The 3 December 2013 Montescaglioso landslide, Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1835–1841 (2014).

Ray, R. L. et al. Remote sensing approaches and related techniques to map and study landslides. In Landslides - Investigation and Monitoring (IntechOpen, 2020). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93681

Manfreda, S. & Ben Dor, E. Chapter 1 - remote sensing of the environment using unmanned aerial systems. In Unmanned Aerial Systems for Monitoring Soil, Vegetation, and Riverine Environments (ed Manfreda, S., Ben Dor, E.) 3–36 (Elsevier, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85283-8.00009-6.

Lucieer, A., de Jong, S. M. & Turner, D. Mapping landslide displacements using structure from Motion (SfM) and image correlation of multi-temporal UAV photography. Progress Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 38, 97–116 (2014).

Turner, D., Lucieer, A. & De Jong, S. M. Time series analysis of landslide dynamics using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Remote Sens. 7, 1736–1757 (2015).

Hussain, Y. et al. Review on the geophysical and UAV-based methods applied to landslides. Remote Sens. 14, 4564 (2022).

Tofani, V., Segoni, S., Agostini, A., Catani, F. & Casagli, N. Technical note: Use of remote sensing for landslide studies in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 299–309 (2013).

Scaioni, M., Longoni, L., Melillo, V. & Papini, M. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: An overview of recent achievements and perspectives. Remote Sens. 6, 9600–9652 (2014).

Casagli, N. et al. Spaceborne, UAV and ground-based remote sensing techniques for landslide mapping, monitoring and early warning. Geoenviron. Disasters 4, 9 (2017).

Kyriou, A. & Nikolakopoulos, K. Landslide mapping using optical and radar data: A case study from Aminteo, Western Macedonia Greece. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 53, 17–27 (2020).

Handwerger, A. L., Roering, J. J. & Schmidt, D. A. Controls on the seasonal deformation of slow-moving landslides. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 377–378, 239–247 (2013).

Delacourt, C., Allemand, P., Casson, B. & Vadon, H. Velocity field of the La Clapière landslide measured by the correlation of aerial and QuickBird satellite images. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31 (2004).

Martha, T. R., Vinod Kumar, K. & September, 2012 landslide events in Okhimath, India—an assessment of landslide consequences using very high resolution satellite data. Landslides 10, 469–479 (2013)

Rossi, G. et al. Multitemporal UAV surveys for landslide mapping and characterization. Landslides 15, 1045–1052 (2018).

Fiorucci, F., Ardizzone, F., Mondini, A. C., Viero, A. & Guzzetti, F. Visual interpretation of stereoscopic NDVI satellite images to map rainfall-induced landslides. Landslides 16, 165–174 (2019).

Soeters, R. & van Westen, C. J. Slope Instability Recognition, Analysis and Zonation, in: Landslides, Investigation and Mitigation. (eds. Turner, A. K. & Schuster, R. L.) (1996).

Borghuis, A. M., Chang, K. & Lee, H. Y. Comparison between automated and manual mapping of typhoon-triggered landslides from SPOT‐5 imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 28, 1843–1856 (2007).

Marcelino, E. V., Formaggio, A. R. & Maeda, E. E. Landslide inventory using image fusion techniques in Brazil. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 11, 181–191 (2009).

Martha, T. R., Kerle, N., Jetten, V. G. & van Westen, C. J. Characterising spectral, spatial and morphometric properties of landslides for semi - automatic detection using object - oriented methods. Geomorphology 116, 24–36 (2010).

Stumpf, A. & Kerle, N. Object - oriented mapping of landslides using random forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 2564–2577 (2011).

Lu, P., Stumpf, A., Kerle, N. & Casagli, N. Object-oriented change detection for landslide rapid mapping. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 8, 701–705 (2011).

Nichol, J. & Wong, M. S. Satellite remote sensing for detailed landslide inventories using change detection and image fusion. Int. J. Remote Sens. 26, 1913–1926 (2005).

Weirich, F. & Blesius, L. Comparison of satellite and air photo based landslide susceptibility maps. Geomorphology 87, 352–364 (2007).

Tsai, F., Hwang, J. H., Chen, L. C. & Lin, T. H. Post-disaster assessment of landslides in southern Taiwan after 2009 Typhoon Morakot using remote sensing and spatial analysis. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 2179–2190 (2010).

Delacourt, C. et al. Remote-sensing techniques for analysing landslide kinematics: A review. Bull. de la. Société Géologique De France 178, 89 (2007).

Leprince, S., Barbot, S., Ayoub, F. & Avouac, J. P. Automatic and precise orthorectification, coregistration, and subpixel correlation of satellite images, application to ground deformation measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 45, 1529–1558 (2007).

Debella-Gilo, M. & Kääb, A. Sub-pixel precision image matching for measuring surface displacements on mass movements using normalized cross-correlation. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 130–142 (2011).

Mondini, A. C. et al. Semi-automatic recognition and mapping of rainfall induced shallow landslides using optical satellite images. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 1743–1757 (2011).

Lu, P. et al. Co-seismic landslide mapping using Sentinel-2 10-m fused NIR narrow, red-edge, and SWIR bands. Landslides 18, 2017–2037 (2021).

Qi, W., Wei, M., Yang, W., Xu, C. & Ma, C. Automatic mapping of landslides by the ResU-Net. Remote Sens. 12, 2487 (2020).

Moosavi, V., Talebi, A. & Shirmohammadi, B. Producing a landslide inventory map using pixel-based and object-oriented approaches optimized by Taguchi method. Geomorphology 204, 646–656 (2014).

Amankwah, S. O. Y. et al. Landslide detection from bitemporal satellite imagery using attention-based deep neural networks. Landslides 19, 2459–2471 (2022).

Williams, J. G. et al. Satellite-based emergency mapping using optical imagery: Experience and reflections from the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 185–205 (2018).

Kääb, A., Altena, B. & Mascaro, J. Coseismic displacements of the 14 November 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikoura, New Zealand, earthquake using the planet optical cubesat constellation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 627–639 (2017).

Qin, Y., Lu, P. & Li, Z., Landslide inventory mapping from & bitemporal 10m Sentinel-2 images using change detection based Markov random field. ISPRS - Int. Archives Photogrammetry Remote Sens. Spat. Inform. Sci. XLII–3, 1447–1452 (2018).

Budha, P. B. & Bhardwaj, A., Landslide extraction from & Sentinel-2 image in siwalik of Surkhet District, Nepal. In ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences vol. IV-5-W29–15 (Copernicus GmbH, 2019).

Ghorbanzadeh, O. et al. Landslide detection using deep learning and object-based image analysis. Landslides 19, 929–939 (2022).

Hölbling, D. et al. Comparing manual and semi-automated landslide mapping based on optical satellite images from different sensors. Geosciences 7, 37 (2017).

Shirvani, Z., Abdi, O. & Buchroithner, M. A. Synergetic analysis of Sentinel-1 and – 2 for mapping historical landslides using object-oriented random forest in the hyrcanian forests. Remote Sens. 11, 2300 (2019).

Lu, P., Qin, Y., Li, Z., Mondini, A. C. & Casagli, N. Landslide mapping from multi-sensor data through improved change detection-based Markov random field. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111235 (2019).

Abad, L. et al. Detecting landslide-dammed lakes on Sentinel-2 imagery and monitoring their spatio-temporal evolution following the Kaikōura earthquake in New Zealand. Sci. Total Environ. 820, 153335 (2022).

Lacroix, P., Bièvre, G., Pathier, E., Kniess, U. & Jongmans, D. Use of Sentinel-2 images for the detection of precursory motions before landslide failures. Remote Sens. Environ. 215, 507–516 (2018).

Yang, W., Wang, Y., Sun, S., Wang, Y. & Ma, C. Using Sentinel-2 time series to detect slope movement before the Jinsha River landslide. Landslides 16, 1313–1324 (2019).

Qu, F., Qiu, H., Sun, H. & Tang, M. Post-failure landslide change detection and analysis using optical satellite Sentinel-2 images. Landslides 18, 447–455 (2021).

Kauth, R. & Thomas, G. The Tasselled Cap—A graphic description of the spectral-temporal development of agricultural crops as seen by LANDSAT. LARS Symp. (1976).

Yarbrough, L. D., Easson, G. & Kuszmaul, J. S. Using at-sensor radiance and reflectance tasseled cap transforms applied to change detection for the ASTER sensor. In International Workshop on the Analysis of Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Images, 141–145 (2005). (2005). https://doi.org/10.1109/AMTRSI.2005.1469857

Han, T. et al. An efficient protocol to process landsat images for change detection with Tasselled Cap Transformation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 4, 147–151 (2007).

Arnett, J. T. T. R., Coops, N. C., Gergel, S. E., Falls, R. W. & Baker, R. H. Detecting stand-replacing disturbance using RapidEye imagery: A tasseled cap transformation and modified disturbance index. Can. J. Remote. Sens. 40, 1–14 (2014).

Thakkar, A. K., Desai, V. R., Patel, A. & Potdar, M. B. An effective hybrid classification approach using tasseled cap transformation (TCT) for improving classification of land use/land cover (LU/LC) in semi-arid region: A case study of Morva-Hadaf watershed, Gujarat, India. Arab. J. Geosci. 9, 180 (2016).

Zanchetta, A., Bitelli, G. & Karnieli, A. Monitoring desertification by remote sensing using the tasselled cap transform for long-term change detection. Nat. Hazards 83, 223–237 (2016).

Liu, Q., Liu, G. & Huang, C. Monitoring desertification processes in Mongolian Plateau using MODIS tasseled cap transformation and TGSI time series. J. Arid Land. 10, 12–26 (2018).

Mostafiz, C. & Chang, N. B. Tasseled cap transformation for assessing hurricane landfall impact on a coastal watershed. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 73, 736–745 (2018).

Lastovicka, J. et al. Sentinel-2 data in an evaluation of the impact of the disturbances on forest vegetation. Remote Sens. 12, 1914 (2020).

Shamsuzzoha, M. & Ahamed, T. Shoreline change assessment in the coastal region of Bangladesh delta using tasseled cap transformation from satellite remote sensing dataset. Remote Sens. 15, 295 (2023).

Basith, A., Matori, A. N., Harahap, I. S. H. & Talib, J. A. Application of Landuse Changes Detection for Identification of Landslide risk Areas in Pulau Pinang Using a Decade of Landsat ETM + Images (2010).

Wu, X., Niu, R., Ren, F. & Peng, L. Landslide susceptibility mapping using rough sets and back-propagation neural networks in the Three Gorges, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 70, 1307–1318 (2013).

brooker, a., fraser, r. h., olthof, i., kokelj, s. v. & lacelle, d. mapping the activity and evolution of retrogressive thaw slumps by tasselled cap trend analysis of a landsat satellite image stack. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 25, 243–256 (2014).

Nitze, I., Heidler, K., Barth, S. & Grosse, G. Developing and testing a deep learning approach for mapping retrogressive thaw slumps. Remote Sens. 13, 4294 (2021).

Vecchiotti, F., Tilch, N. & Kociu, A. The use of TERRA-ASTER satellite for landslide detection. Geosciences 11, 258 (2021).

De Marco, A. & Di Pierro, M. Le argille in frana di pomarico (Matera). Studio granulometrico e mineralogico. Società Italiana Di Mineralogia E Petrologia: SIMP 37, 213–227 (1981).

Bozzano, F., Cherubini, C., Floris, M., Lupo, M. & Paccapelo, F. Landslide phenomena in the area of Pomarico (Basilicata–Italy): Methods for modelling and monitoring. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 27, 1601–1607 (2002).

Doglioni, A., Casagli, N., Nocentini, M., Sdao, F. & Simeone, V. The landslide of Pomarico, South Italy, occurred on January 29th 2019. Landslides 17, 2137–2143 (2020).

Perrone, A. Lessons learned by 10 years of geophysical measurements with civil protection in Basilicata (Italy) landslide areas. Landslides 18, 1499–1508 (2021).

Scorza, F., Pilogallo, A., Saganeiti, L. & Murgante, B. Natura 2000 areas and sites of national interest (SNI): Measuring (un)Integration between naturalness preservation and environmental remediation policies. Sustainability 12, 2928 (2020).

Lanfredi, M., Coluzzi, R., Imbrenda, V., Macchiato, M. & Simoniello, T. Analyzing space–time coherence in precipitation seasonality across different European climates. Remote Sens. 12, 171 (2020).

Samela, C. et al. Multi-decadal assessment of soil loss in a Mediterranean Region characterized by contrasting local climates. Land 11, 1010 (2022).

Perrone, A. et al. A multidisciplinary approach for landslide residual risk assessment: The Pomarico landslide (Basilicata Region, Southern Italy) case study. Landslides 18, 353–365 (2021).

Gascon, F. et al. Copernicus Sentinel-2A calibration and products validation status. Remote Sens. 9, 584 (2017).

Coluzzi, R. et al. Exploring the use of Sentinel-2 data to monitor heterogeneous effects of contextual drought and heatwaves on Mediterranean forests. Land 9, 325 (2020).

Samela, C., Coluzzi, R., Imbrenda, V., Manfreda, S. & Lanfredi, M. Satellite flood detection integrating hydrogeomorphic and spectral indices. GISci. Remote Sens. 59, 1997–2018 (2022).

Caballero, I., Ruiz, J. & Navarro, G. Sentinel-2 satellites provide near-real time evaluation of catastrophic floods in the West Mediterranean. Water 11, 2499 (2019).

Greco, S. et al. Late spring frost in Mediterranean Beech forests: Extended Crown Dieback and Short-Term effects on Moth communities. Forests 9, 388 (2018).

Crist, E. P. & Cicone, R. C. A physically-based Transformation of Thematic Mapper Data—the TM tasseled Cap. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. GE-22, 256–263 (1984).

Oliveira, E. R., Disperati, L., Cenci, L., Gomes Pereira, L. & Alves, F. L. Multi-index image differencing method (MINDED) for flood extent estimations. Remote Sens. 11, 1305 (2019).

Shi, T. & Xu, H. Derivation of tasseled cap transformation coefficients for Sentinel-2 MSI at-sensor reflectance data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 12, 4038–4048 (2019).

Fraser, R. H. et al. Detecting landscape changes in high latitude environments using Landsat trend analysis: 1. Visualization. Remote Sens. 6, 11533–11557 (2014).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 21, 6 (2020).

Bontemps, N., Lacroix, P. & Doin, M. P. Inversion of deformation fields time-series from optical images, and application to the long term kinematics of slow-moving landslides in Peru. Remote Sens. Environ. 210, 144–158 (2018).

Coluzzi, R., Imbrenda, V., Lanfredi, M. & Simoniello, T. A first assessment of the Sentinel-2 level 1-C cloud mask product to support informed surface analyses. Remote Sens. Environ. 217, 426–443 (2018).

Shahtahmassebi, A., Yang, N., Wang, K., Moore, N. & Shen, Z. Review of shadow detection and de-shadowing methods in remote sensing. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 23, 403–420 (2013).

Li, S., Sun, D. & Yu, Y. Automatic cloud-shadow removal from flood/standing water maps using MSG/SEVIRI imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 34, 5487–5502 (2013).

Magno, R. et al. AgroShadow: A new Sentinel-2 cloud shadow detection tool for precision agriculture. Remote Sens. 13, 1219 (2021).

Lu, H. et al. Landslides information extraction using object-oriented image analysis paradigm based on deep learning and transfer learning. Remote Sens. 12, 752 (2020).

Zhong, X., Xu, X., Chen, W., Liang, Y. & Sun, Q. Characteristics of loess landslides triggered by the 1927 Mw8.0 earthquake that occurred in Gulang County, Gansu Province, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rosa Coluzzi contributed to conceptualization and methodology; Caterina Samela contributed to data integration and performance evaluation; Rosa Coluzzi and Vito Imbrenda contributed to analysis of satellite data; Letizia Pace contributed to analysis of orthomosaic; Angela Perrone contributed to geological and geomorphological interpretation; Salvatore Manfreda contributed to acquire and analyze UAS data; Rosa Coluzzi contributed to the original draft preparation; all the authors contributed to writing, review and editing the final version of the manuscript; Maria Lanfredi contributed to funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coluzzi, R., Perrone, A., Samela, C. et al. Rapid landslide detection from free optical satellite imagery using a robust change detection technique. Sci Rep 15, 4697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89542-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89542-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cascading impacts of 2025 June-July multi-hazard episodes in the Western Himalayas: Evidence through remote sensing observations and Google Earth Engine

Natural Hazards (2025)

-

Integrated time-lapse ERT and airborne laser scanning–photogrammetry DEM analysis of a reservoir-induced landslide in central Poland

Landslides (2025)