Abstract

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022, Ukraine has experienced different types of abandoned cropland, such as unused and unattended cropland, as a result of war damage, agricultural infrastructure destruction, and refugee outflows. Common methods for detecting abandoned cropland have difficulty effectively identifying and distinguishing these different types. This study proposes a Dual-period Change Detection method to reveal the spatial distribution and changes of different types of abandoned cropland in Ukraine, which can aid in agricultural assessments and international assistance in conflict-affected areas. The method mainly utilizes time-series NDVI data to fit the crop curves corresponding to cropland on a pixel-by-pixel basis, and then establishes discrimination rules for different types of abandoned cropland based on the crop curves, so as to detect unused cropland in the pre-conflict period (2015–2021) as well as unused cropland and unattended cropland in the post-conflict period (2022–2023). Finally, the detection results are validated and accuracy assessed using medium and high resolution spatiotemporal remote sensing imagery interpretation. The results show that the overall accuracy of the abandoned cropland extraction in Ukraine ranges from 83 to 96% during the study period. Before the conflict, the national average unused rate was 1.6%, with the lowest in 2021 and the highest in 2018. In 2022, the unused cropland area was approximately twice the average unused area before the conflict, and it was widely distributed, with the area of unattended cropland reaching 462,000 hectares, mainly in the eastern part of Ukraine. In 2023, compared to 2022, the unused cropland area decreased by 67.8%, while unattended cropland increased by 116.7%. Both types of abandoned cropland exhibited spatial clustering, with major clusters identified in the Crimea region, Kherson Oblast, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, and Donetsk Oblast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, research on land use and agricultural sustainability has increased worldwide1,2,3,4,5,6. Land is a crucial resource for human production and livelihood, and its proper utilization is essential for achieving food security, environmental protection, and economic development7,8,9. In the agricultural sector, the rational use and management of cropland are of significant importance in enhancing crop yields, reducing land degradation, and maintaining ecological balance10,11,12.

As an important agricultural country in Europe, Ukraine has vast cropland and rich agricultural resources13,14,15. However, with the continuous and escalating conflict between Russia and Ukraine, sudden and large-scale armed conflicts caused damage to Ukraine’s cropland and impacted crop production16,17,18,19, resulting in the emergence of large areas and different types of abandoned cropland20,21. Therefore, the study of abandoned cropland in Ukraine has become particularly important to understand the status quo, problems and restoration needs of cropland before and after the conflict22,23.

Over the past few decades, remote sensing technology has played a crucial role in land use and agricultural monitoring24,25,26,. Regarding abandoned cropland information extraction, methods can generally be classified into three categories: direct classification based on land features27,28,29,3031, comparative analysis based on two or multiple periods of land use types32,32,34, and change detection based on temporal remote sensing indices35,35,36,38. Among them, compared with the other two types of methods, the detection method based on time-series remote sensing index change can obtain more detailed information about abandoned cropland (such as the start time, duration, scope, intensity and spatial structure of abandoned cropland), and also has higher accuracy and advantages that the other two types of methods do not have34. Such methods usually use the time series change of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to simulate and detect cropland crop growth, so as to distinguish active cropland from abandoned cropland39.

There are numerous methods to acquire temporal NDVI data. Data with high spatial resolution can be derived from Landsat or Sentinel satellite observations, but they often suffer from low temporal resolution and additional influences from cloud cover and atmospheric interference, limiting their application in large-area abandoned cropland detection34. In comparison, MODIS satellite sensor’s NDVI products, known for their high temporal resolution and superior quality control, have become a standard index for studying cropland abandonment and vegetation growth across large regions40,40,42.

Abandoned cropland is typically defined as land that has not been tilled for at least 2–5 years. However, considering the unique circumstances in Ukraine due to the ongoing conflict, this study defines abandoned cropland as land that has not been normally cultivated for at least one year. In detecting abandoned cropland under this definition, a long-term and continuous management patterns sequence of Ukrainian cropland is also generated43. The long-term sequence of cropland management patterns can serve as an indicator of land management intensity, allowing for further differentiation of abandoned cropland. Due to damaged agricultural infrastructure and refugee outflows, the post-conflict cropland management patterns in Ukraine can be classified as normal cultivation, unused, and unattended cropland. Here, “unused” refers to cropland with no sowing activities, while “unattended” indicates cropland that has been sown but lacks or has no management44,45. Both categories fall under the umbrella of abandoned cropland, complicating the application of commonly used land cover classification or change detection models due to the complex operational conditions46.

In this context, we develop a Dual-period Change Detection (DCD) method for the Ukrainian region. This method can not only detect unused cropland that occurred during the pre-conflict period (2015–2021) but also effectively identify cropland in unused or unattended states during the post-conflict period (2022–2023). Through the implementation and validation of this method, valuable information and scientific evidence will be provided for agricultural management, decision-making, and agricultural recovery in Ukraine and similar regions.

Materials and methods

Overview of the study area

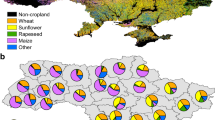

Ukraine is located in Eastern Europe, with a total area of 603,700 square kilometers. It is an important agricultural country in Europe. The landscape of Ukraine is mainly composed of plains and hills, with plains accounting for about 95% of the land area. More than 60% of the land is used for cultivation, and Ukraine possesses two-fifths of the world’s black soil area, which is rich in organic matter and nutrients13,14,15. This fertile soil is highly suitable for crop growth, earning Ukraine the title of "Europe’s breadbasket." In addition to sharing a border with Russia, Ukraine is also adjacent to countries such as Poland, Belarus, Moldova, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia. The geographical location and land use classification of Ukraine are shown in Fig. 1(Data sources and coordinate projection methods are described in Sect. “Data” and Sect. “Data preprocessing” respectively. Land classification results are derived from appropriate combinations of IGBP’s Global Vegetation classification Scheme).

In Ukraine, the main crops grown include barley, buckwheat, corn, millet, oats, rye, and wheat. The agricultural production follows two planting seasons: spring planting and autumn planting47. Spring planting starts from March and continues until May, focusing on crops such as corn, barley, oats, buckwheat, and millet, which are harvested in September of the same year. Autumn planting takes place in August each year, mainly for winter wheat and rye, which are harvested in July of the following year. Agriculture plays a significant role in Ukraine’s GDP, and it also has a crucial impact on global food supply and agricultural import and export48,49.

Data

The data used in this study mainly consists of five parts. It includes NDVI time series data, land use type data, medium and high resolution remote sensing image data, and vector data of Ukrainian administrative divisions.

NDVI time series data

The temporal NDVI data used in this study primarily comes from the MODIS Vegetation Index product MOD13Q1, which can be obtained from LAADS DAAC (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/). It includes 250 m resolution NDVI data and its quality control data, synthesized every 16 days using the MVC method. In this study, standard image products with strip numbers h19v03, h19v04, h20v03, h20v04 and h21v04 were used to establish multi-temporal remote sensing images from NDVI data of 23 time phases every year from 2015 to 2023.

Land use type data

The land use type data used in this study is the MODIS Level-3 Land Cover Type product MCD12Q1 released in 2020. This data is generated based on a decision tree algorithm and has an overall accuracy of approximately 75%50. It covers the entire globe and has five different land use classification schemes. The spatial resolution is 500 m, and it can also be obtained from LAADS DAAC.

Medium-resolution remote sensing image data

The medium resolution remote sensing image data in this study came from Landsat 8–9 satellite, which has a spatial resolution of 30 m, and can obtain continuous observation images at a certain time interval on a global scale. The data can be freely viewed or downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) EarthExplorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/), LandsatLook (https://landsatlook.usgs.gov/), and GloVis (https://glovis.usgs.gov/).

High-resolution remote sensing image data

The high-resolution remote sensing image data used in this study is Esri World Image, which can be freely viewed on EarthExplorer. This data includes multiple satellite sensors and data providers, including commercial satellite data providers such as DigitalGlobe, GeoIQ, and public data providers such as NASA. Overall, the data can be classified into high, medium, and low levels based on spatial resolution. High-resolution data typically has a resolution between 0.3 m and 2 m, medium-resolution data has a resolution between 2 and 30 m, and low-resolution data has a resolution above 30 m. It should be noted that the specific data resolution and availability may vary by region, as the image data in different regions may come from different satellites and data providers.

Administrative boundary vector data of Ukraine

The administrative boundary vector data includes country, state (municipality), and district (county) level administrative boundary vector data. It can be freely obtained from the Global Administrative Areas database (GADM) freely available public map data set (https://gadm.org/), version 3.6, with the WGS84 coordinate reference system.

Methodology

The DCD method flow is shown in Fig. 2 and includes the following steps:

1) Data preprocessing; 2) Crop curve reconstruction; 3) Region of interest identification; 4) Unused cropland detection; 5) Self-supervised classification; 6) Accuracy validation.

Data preprocessing

After collecting the MODIS NDVI and land use type data, data preprocessing is performed to ensure data quality and consistency. This includes band extraction, mosaic, reprojection, stitching, resampling, clipping, re-encoding, and masking operations.

First, the IGBP scheme classification result bands from the MCD12Q1 data product and the NDVI and quality control (SummaryQA) bands from the MOD13Q1 data product are extracted using the MODIS Reprojection Tool (MRT). Then, the bands are stitched, projected, mosaicked, and resampled based on their spatial positions. The spatial reference system used for stitching is the WGS84 datum, and the projection is performed using the Albers equal area projection (projection parameters are shown in Table 1). The resampling interval is set to 250 m.

Finally, the data is clipped and re-encoded based on the national boundary vector information from the administrative boundary data of Ukraine. This ensures the consistency of the bands in the Ukraine region. The spatial information of cropland is contained in the IGBP scheme classification result, and it can be highlighted separately through masking processing.

Crop curve reconstruction

To better characterize crop growth features using NDVI data, it is necessary to reconstruct high-quality NDVI curves, referred to as crop curves, that better align with crop growth logic. In this study, an open-source R package called “phenofit”51 is used for crop curve reconstruction, specifically utilizing its curve fitting functionality. Modifications were made to the package to suit the research requirements, including weight initialization, preprocessing of vegetation index inputs, curve fitting, and weight updating.

The reconstruction of the NDVI time series should rely primarily on information from high-quality points but should also extract limited information from edge points and poor-quality points52,53. In this study, weight initialization is based on the quality control (QC) information of the remote sensing images (the SummaryQA band in MOD13Q1). The NDVI observations are categorized into three classes: good, moderate, and poor, with corresponding weights of maximum (\({w}_{max}\)), middle (\({w}_{mid}\)), and minimum (\({w}_{min}\)). Actual NDVI values are usually greater than contaminated remote sensing observations54, indicating that contaminated observations can still provide valuable information, and \({w}_{min}\) should be greater than zero. If \({w}_{min}\)=0.0, the “poor” data points will be completely ignored. Therefore, in this study, \({w}_{max}\), \({w}_{mid}\), and \({w}_{min}\)are set to 1.0, 0.5, and 0.2, respectively, for weight initialization55,56.

The curve fitting approach is similar to weighted linear regression57, aiming to minimize the cost function J, defined as the weighted sum of squared errors, where weights play a regulating role and directly impact the curve fitting results. J is described as follows:

In the equations, the subscript i represents the i-th element. y represents the original NDVI time series, ŷ represents the fitted results, and w represents the weights during the curve fitting process.

Due to the uncertainty of the input sequence values, preprocessing of the NDVI time series data is necessary. If the absolute difference between \({y}_{i}\) and \({y}_{mov,i}\) is greater than twice the standard deviation of the entire time series, the point is marked as a "spike." Here, \({y}_{i}\) is the i-th observed value of the input NDVI, and \({y}_{mov,i}\) is the corresponding moving average of three points. Spike values containing missing values are discarded since phenotypic fitting can handle unevenly spaced sequences.

Furthermore, the upper and lower bounds of the NDVI time series (referred to as ylu) are determined based on high-quality observations. They are primarily used to constrain contaminated NDVI values within a reasonable range, especially during non-drought growing seasons with significant snowfall. Points exceeding the ylu range are considered suspicious, and their values and weights are reassigned to \({y}_{min}\) (the lower limit of ylu) and \({w}_{min}\), respectively.

Commonly used curve fitting functions include weighted Savitzky-Golay (wSG)58, weighted Harmonic Analysis of Time Series (wHANTS)59, and weighted Whittaker (wWHIT)55. Typically, wSG is optimal for vegetation experiencing abrupt changes (e.g., deforestation or forest fires)60, wHANTS is suitable for vegetation with explicit and stable growing seasons59,61, and wWHIT is applicable to vegetation with dynamic changes during the growing season (e.g., planting in abundant or drought years)62. Compared to wSG and wHANTS, wWHIT is more robust against outliers55. It can capture vegetation seasonal signals even when more than 30% of the input NDVI time series is contaminated. Given the vast territory and diverse crop types in Ukraine, this study selects wWHIT as the default option for curve fitting.

After each iteration of curve fitting, a weight updating function is applied to adjust the weights of each point in the time series. Points located above or below the fitted curve are underestimated or overestimated. In the presence of contamination in the NDVI time series, the values are typically lower than normal63. Relatively higher values (points underestimated during the curve fitting process) are more likely to have better quality compared to lower values (points overestimated). Therefore, the weight updating function tends to increase the weights of underestimated points and decrease the weights of overestimated points to minimize the contamination impact and approach the upper envelope of the NDVI time series. Alternatively, it reduces the weights of outliers to minimize their interference. Outliers in phenotypic fitting are defined using the same strategy as the bisquare function in robust regression55.

Weight updating through the weight updating function enhances the robustness of phenotypic fitting in capturing NDVI vegetation seasonality signals. Advanced weight updating functions include the modified bisquare weight updating function (wBisquare)55, the weight updating function of TIMESAT (wTSM)64, and the weight updating function of Chen et al. (wChen)58. Among them, wBisquare has stable performance and is the default choice in this study.

Region of interest identification

Typically, unused cropland exhibit lower NDVI values during the growing season, while normal cultivation (with crop growth) display higher NDVI values35,42. Therefore, the identification and localization of regions of interest are fundamental for detecting land changes.

By analyzing the seasonal characteristics of crop plantings in historical periods in Ukraine, it is known that the crop planting calendar in Ukraine varies significantly based on geographical and crop type differences (USDA). Directly defining the growing season within fixed periods can lead to inaccurate detection results42. Moreover, the regions of interest that need to be considered when detecting cropland management patterns before and after conflicts also vary. Therefore, in this study, a region of interest identification module was utilized to first identify and label the regions of interest in crop growth curves, and then divide them into the growth and harvesting portions, as shown in Fig. 3.

First, based on the common seasonal characteristics of various crop plantings in Ukraine (USDA), the preliminary range of crop maturity season was defined as spanning from Julian day 129 (May 9th or May 10th in a leap year) to Julian day 240 (August 28th or August 29th in a leap year). Then, within this initial range of the crop maturity season, the maximum value was searched, and its corresponding date was considered as the crop maturity date. Finally, based on the crop maturity date, as well as the duration of the growth period and the harvesting period, the crop’s growing season and harvesting season were determined.

Due to variations in the duration of the growth and harvesting periods for different crops, this study shortened the interested region of the growing season to 64 days based on the seasonal characteristics of crops in the study area (where barley, with a growth period of two months, has the shortest growth period). Additionally, the interested region of the harvesting season was extended to 64 days (as the harvesting period for crops in the study area generally does not exceed two months).

Unused cropland detection

During the unused cropland detection phase, the algorithm only needs to focus on the crop growing season65. Typically, statistical indicators such as the mean and standard deviation of NDVI values during the growing season for different years are used. Then, a threshold segmentation is applied to the crop growth curve to detect unused years. However, through experimental investigation, it has been found that the standard deviation indicator can exhibit exploding (too large) or disappearing (too small) values during the actual detection process. Therefore, in this study, a relative ratio (percentage) indicator is used to determine confidence intervals and detect unused cropland.

First, let’s assume that the crop index C is correlated with the i (year) and the j (ordinal number of the observation point), as shown in Eq. (2):

Here, \(NDVI(i,j)\) represents the NDVI value of the j-th observation point during the growing season of the i-th year, and \(Mean\_NDVI(OtherYears,j)\) represents the average NDVI value observed at the j-th observation point during the growing season of all other years from 2015 to 2021.

Then, the following rule is used to determine whether the land is unused:

Here, N is a constant. This study assumes that if the NDVI values for 64 consecutive days during the growing season, when compared to other years, consistently remain at a lower level, then the corresponding year (i) is a unused year.

It should be noted that the crop index C is greatly influenced by the average NDVI values of other years. However, the average NDVI values of other years may not be entirely reliable in certain cases, such as when there are unused years among the other years, which can cause a decrease in the average values. Therefore, this study introduces a threshold valve before determining unused status, as shown in Eq. (4), to adjust the threshold value N based on different situations.

Here, \(Std\_NDVI(OtherYears,j)\) represents the standard deviation of the six NDVI values for the j-th observation point during the growing season of other years from 2015 to 2021.

This study assumes that when the standard deviation of the NDVI values for other years is greater than 0.1, there is a high likelihood of unused years (with a decrease in the average values). Therefore, the threshold value is appropriately increased, and the accurate values of the threshold are determined through rough training with limited samples, which are −15% and −25%, respectively.

Self-supervised classification

Based on the unused cropland detection results, the crop curves corresponding to unused years are first removed from the pixels, allowing for statistical analysis of the crop curves for normal cultivation years. Since there are two possible representations of abandoned land post-conflict, namely horizontal and vertical patterns, neither a single dimension nor two dimensions can achieve binary segmentation for all three cases. This is illustrated in Fig. 4(A) and 4(B).

To address this, a statistical quantity called the Crop Integral (S) is further constructed as a statistical indicator for binary segmentation. Its expression is given by Eq. (5):

Here, the lower bound of the integral (first) and the upper bound (finally) represent the first day of the growing season and the last day of the harvesting season in the region of interest (as shown in Fig. 4), and NDVI is the NDVI value corresponding to a specific time (t).

However, polynomial fitting requires significant computational power51. Therefore, in this study, a geometric approximation method is used to simplify the process of solving S, as shown in Eq. (6), thereby improving the detection efficiency.

Here, n represents the total number of periods between the growing season and the harvesting season in the remote sensing image, and \(NDVI_{i}\) represents the normalized vegetation index value for a specific period.

From the historical Crop Integral values (\({S}_{1},{S}_{2},\cdots ,{S}_{n}\)) of cropland, the mean statistical indicator (\(\overline{S }\)) is obtained. Then, based on the binary segmentation percentages (n, m), the confidence interval [a, b] for the sample values is further determined as the two thresholds for binary segmentation. The confidence interval is determined by (\(\overline{S }\)) and n, as shown in Eq. (7).

Here, n and m are empirical values for the binary segmentation, which need to be determined through comparative experimental analysis and evaluation66.

After binary segmentation, the cropland corresponding to a particular year is divided into three categories: high Crop Integral values, representing unattended cropland; normal values, representing regular cultivation; and low values, representing unused cropland. This is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Accuracy validation

Due to the difficulties in conducting ground surveys of cropland in Ukraine67, the accuracy of the proposed method in this study is evaluated using a visual validation approach with high-resolution reference image and medium-resolution Landsat 8–9 images68. The accuracy assessment process mainly includes random sampling, visual interpretation, and metric calculation68,67,70.

Firstly, random sampling is performed on the results of abandoned cropland extraction based on year and category to ensure that the sample points are representative of different years and categories66. The number of sample points for each year and category is set to 50, resulting in a total of 1000 sample points. Then, based on the sample point information, the temporal and spatial positions of these sample points are marked on the remote sensing images. Visual interpretation is conducted on the multi-temporal images corresponding to each sample point. The change characteristics of cropland on the images are observed, and the management patterns corresponding to each sample point’s year is determined based on crop phenology characteristics. The results of visual interpretation are recorded. Finally, the visual interpretation results are compared with the algorithm extraction results, and the comparison results for each category of sample points are statistically analyzed to calculate accuracy metrics.

In this study, a confusion matrix is used to evaluate various metrics, including Producer Accuracy (PA), User Accuracy (UA), Overall Accuracy (OA), and Kappa coefficient. The confusion matrix is a two-dimensional table used to compare the classification results between visual interpretation and extraction results, as shown in Table 2.

Here, Overall Accuracy (OA) represents the proportion of correctly classified samples to the total number of samples. The formula for OA is shown in Eq. (8).

Overall Accuracy measures the classification accuracy of the model across all categories and is a commonly used evaluation metric. However, when the sample sizes of different categories are imbalanced, the accuracy may not fully reflect the classification results. Therefore, other evaluation metrics need to be used to comprehensively assess the classification results.

The Kappa coefficient is a measure of consistency used to evaluate classification results. For classification problems, consistency refers to whether the model’s predicted results align with the actual classification results. OA directly reflects the proportion of correct classifications, is easy to calculate, but when there is class imbalance during classification, some categories may have low values even when OA is high. The Kappa coefficient can reflect this issue, as it decreases significantly when there are poor results for a particular class. The formula for Kappa is shown in Eq. (9).

In addition to evaluating the accuracy and consistency of the overall classification results, it is also necessary to evaluate the classification results for individual categories. Producer Accuracy (PA) and User Accuracy (UA) are commonly used metrics to evaluate the classification results of a specific category from two perspectives.

Producer Accuracy (PA), also known as mapping accuracy, refers to the ratio of the total number of pixels correctly assigned to a specific class (diagonal value) to the total number of pixels assigned to that class by the classifier (column sum). Taking unused cropland as an example, the formula for PA is shown in Eq. (10).

The corresponding metric is User Accuracy (UA), which represents the ratio of the number of pixels correctly classified into a specific class by the classifier (diagonal value) to the total reference number of pixels for that class (row sum). Using unused cropland as an example, the formula for UA is shown in Eq. (11).

In summary, by calculating metrics such as Producer Accuracy (PA), User Accuracy (UA), Overall Accuracy (OA), and Kappa coefficient, the performance of the model in abandoned land detection can be comprehensively evaluated.

Results

Pre-conflict period

Spatial and temporal distribution of unused cropland

Based on the cropland management patterns sequence of Ukraine’s cropland from 2015 to 2021 output by the unused cropland detection module of the DCD method, the map visualization of unused cropland distribution is shown in Fig. 6(A) - 6(G).

Overall, the trend of unused cropland area in Ukraine is relatively unstable, with significant changes between different years. Among them, the largest unused cropland area was in 2018, approximately 1.046 million hectares, while the smallest was in 2021, around 0.222 million hectares.

In terms of spatial distribution, unused cropland in Ukraine from 2015 to 2021 is predominantly located in the southern region, particularly near the Crimea region. To further explore the spatial distribution characteristics of unused cropland, this study extracted the cropland pixels that remained unused for two or more consecutive years during this period. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

By analyzing the unused cropland pixels, it was found that there were approximately 138,000 hectares of cropland in Ukraine from 2015 to 2021 that exhibited continuous unused behavior for two or more years. Among them, over 95% of the continuous unused cropland pixels remained unused for two consecutive years, while the proportion of pixels with continuous unused for multiple years (three years or more) was relatively small. The periods of continuous unused were concentrated mainly in 2017–2018, 2018–2019, and 2019–2020, with the majority of continuous unused cropland pixels located in the southern region of Ukraine. There was a certain clustering effect of continuous unused cropland pixels depending on the time period.

Accuracy of unused cropland detection

The accuracy assessment of the unused cropland map in Ukraine from 2015 to 2021 yielded various accuracy metrics, as shown in Table 3.

According to the accuracy validation results, the Producer Accuracy (PA) for identifying normal cultivation cropland ranged from 0.94 to 0.98, while the User Accuracy (UA) ranged from 0.76 to 0.91. This high level of accuracy in detecting normally cultivated cropland plots provides a solid foundation for the detection of unused cropland.

Regarding unused cropland detection, the Producer Accuracy (PA) values ranged from 0.70 to 0.93, while the User Accuracy (UA) values ranged from 0.95 to 0.98. This indicates that the algorithm also demonstrates high accuracy in detecting unused cropland.

Overall, from 2015 to 2021, the Overall Accuracy (OA) values ranged from 0.83 to 0.93, and the Kappa coefficient (Kappa) values ranged from 0.66 to 0.86. This means that the algorithm not only exhibits high accuracy in the overall unused cropland detection task but also demonstrates high consistency in unused cropland detection.

In summary, the unused cropland detection module of the DCD method proposed in this study generally exhibits high accuracy and consistency. It can effectively identify normally cultivated cropland and unused cropland, laying the foundation for the self-supervised classification module of this method.

Post-conflict period

Binary segmentation thresholds selection and accuracy

To explore the optimal binary segmentation thresholds (n and m), this study conducted comparative experiments and analysis on the value of n. Three sets of tests were performed with n values set at 15%, 20%, and 25% respectively. The results of the comparative experiments are recorded in Table 4.

For normally cultivated cropland and unused cropland, each set of tests calculated the metrics for 2022, 2023, and the overall two-year results separately. According to the calculated metrics, it can be seen that the experiment with n = 20% generally achieved higher Producer Accuracy (PA) and User Accuracy (UA) in most cases.

In 2022, the experiment with n = 20% exhibited relatively high PA and UA for both normally cultivated cropland and unused cropland. The PA and UA for normally cultivated cropland were 0.98 and 0.83, respectively, while for unused cropland, they were 0.8 and 0.98, respectively. In 2023, the experiment with n = 20% also achieved high PA and UA, with both normally cultivated cropland and unused cropland reaching PA and UA values of 0.96. Therefore, the overall two-year results also favored the n = 20% experiment, with PA and UA for normally cultivated cropland at 0.97 and 0.89, respectively, and for unused cropland at 0.88 and 0.97, respectively.

Furthermore, the overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient of the n = 20% experiment were higher compared to the other comparative groups. In 2022, the overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient of the n = 20% experiment were 0.89 and 0.78, respectively. In 2023, they were 0.96 and 0.92, respectively.

Therefore, using n = 20% achieved better results in terms of accuracy and consistency compared to n = 15% and n = 25%. These experimental results indicate that selecting n = 20% as the threshold in the self-supervised classification of unused cropland in Ukraine in 2022–2023 can yield better results.

As for the value of m, in distinguishing whether cropland is under normal cultivation, due to the inability to effectively validate some cases of unattended practices (e.g., delayed harvested crops and delayed plowing) through visual assessment methods, the determination of the threshold had to rely on the verifiable portion (evidence of unharvested crops and lack of plowing). This study conducted four sets of tests with m values set at 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% respectively. Random sampling was performed from the results of unattended cropland detection in each group, and the number and percentage of samples with no harvest or plowing were counted. The results of the comparative experiments are recorded in Table 5.

Based on the experimental results, when m was set to 20%, the percentage of samples with no harvest or plowing in 2022 was 34%, in 2023 it was 38%, and the overall two-year percentage was 36%, which was the highest among all the experimental groups. This indicates that setting m as 20% in this experiment can better detect unattended cropland.

Furthermore, through analysis, it can be observed that the percentage of samples with no harvest or plowing in 2023 was significantly higher than in 2022 for all experimental groups. This suggests that unattended cropland in Ukraine showed an expanding trend in 2023 compared to 2022.

In summary, when the two thresholds (n and m) in the self-supervised classification module are both 20%, better results can be obtained in the detection of abandoned cropland in Ukraine in 2022–2023. The overall accuracy (OA) of unused cropland was 93%, and the Kappa coefficient was 0.85. In the aspect of unattended cropland detection, it can ensure that more than one-third of the cropland in the test results is unattended cropland with no harvest and ploughing, and the remaining two-thirds are abnormal cropland whose crop Integral is significantly higher than that of previous years (It is very likely to be an unattended cropland that lacks management).

Distribution of abandoned cropland

The spatial distribution of abandoned cropland in Ukraine for the years 2022–2023, as outputted by the self-supervised classification module in the DCD method with thresholds of n = 20% and m = 20%, is shown in Fig. 8(A) and 8(B).

Overall, there was a significant increase in the quantity of abandoned cropland in Ukraine during the years 2022–2023 compared to the period of 2015–2021. In 2022, the area of unused cropland was approximately 1.257 million hectares, unattended cropland covered around 0.462 million hectares, resulting in a total of approximately 1.72 million hectares of abandoned cropland. In 2023, the area of unused cropland decreased to approximately 0.404 million hectares, while unattended cropland expanded to approximately 1.002 million hectares, resulting in a total of approximately 1.407 million hectares of abandoned cropland.

Spatial analysis of the unused cropland parcels in Ukraine during 2022–2023 reveals that in 2022, the unused cropland in the southern region of Ukraine still exhibited an aggregation effect, with a notable spatial diffusion trend compared to 2015–2021. The expansion of unused cropland showed a spreading pattern from the southern region to other parts of the country. However, in 2023, the trend of unused cropland in Ukraine shifted from diffusion to dissipation, mainly concentrated in the eastern part of the country and distributed more sparsely.

Conversely, the unattended cropland in Ukraine was primarily distributed in the eastern region in 2022, with a relatively scattered distribution. However, in 2023, there was a clear clustering effect observed in the unattended cropland in the eastern region of Ukraine, with a significantly expanded range compared to 2022.

In conclusion, the area of abandoned cropland in Ukraine nearly doubled in 2022 compared to previous years and was distributed throughout the country. Although there was a slight decrease in the area of abandoned cropland in 2023, it remained at a high level and exhibited a clustering trend compared to previous years.

Discussion

Contributions of the current study

The contributions of this study mainly include:

1. In this study, the distribution of cropland operation patterns across Ukraine in 2015–2023 is presented in detail, with trend analysis of the area and rate of abandonment. About 90% of the 27 administrative districts show an increasing trend in the area of abandonment in 2022. Among them, a significant increase in the rate of abandonment of cropland was observed in the Crimea, Donetsk, Kherson, Odessa and Zaporizhzhya oblasts. This is shown in Fig. 9.

2. Currently, little is known about the ecological and social impacts of abandoned cropland across Ukraine. The map of abandoned cropland developed in this study provides a database that can be used by researchers to explore the factors influencing the abandonment of cropland in Ukraine or to analyze the potential risks of abandonment in Ukraine. For example, as can be seen in Fig. 10(A) Fig. 10(B), the area of abandoned cropland in Odessa Oblast experienced a significant increase followed by a decrease during 2022–2023. Possible reasons for this include 1) the shift of the main areas of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict; 2) the adjustment of Russia’s policy of blockading the Black Sea; and 3) changes in Ukraine’s agricultural policy.

3. This study formulated rules for discriminating cropland management patterns based on the DCD method. This is of some guiding significance for the automatic identification of abandoned cropland in other regions using remote sensing data. Among them, this study introduced the region of interest identification module to adaptively divide the focus area of time series NDVI, which makes the detection method more accurate, flexible and scientific, and improves the detection efficiency. The unused cropland detection module makes the detection mechanism more realistic by introducing a threshold valve, which effectively improves the adaptive ability and detection accuracy. The self-supervision detection module can effectively distinguish different types of abandoned cropland through binary segmentation on the basis of the results of unused cropland detection. In conclusion, the above three modules can provide a convenient path for other researchers engaged in large regions and multiple types of cropland.

Comparison with other studies conducted in Ukraine

Several researchers have already extracted localized areas or some types of abandoned cropland in Ukraine based on remote sensing data sources. For example, Skakun et al.71 used freely available satellite data and machine learning methods to map cropland in 2013 and 2018 in southeastern Ukraine and further derived the corresponding changes in cropland area. Qadir et al.72 used Sentinel-1 (S1) synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery to quantify between 2021–2022 the Changes in sunflower acreage in Ukraine. These two studies relied only on data from two periods to identify abandoned cropland, making it difficult to distinguish between abandoned and fallow land.

Deininger et al.73 used 4 years of satellite imagery (2019–2022) of 10,125 Ukrainian VDCs to estimate the impact of the Russian-initiated war on the area and the expected yields of winter crops aggregated from the field level. He et al.74 used the Sentinel dataset based on the GEE platform using the time-weighted dynamic time regularization (TWDTW) method to map the distribution of abandoned lands in six oblasts of eastern Ukraine. Whereas, the area discussed in this paper is the whole territory of Ukraine and the overall accuracy of the maps for cropland categorization in this study ranges from 83 to 96%. In the study conducted by Skakun et al.71, the accuracies of estimation for stabilized non-cropland, stabilized cropland, increased cropland, and decreased cropland were 97.1 ± 1.0%, 96.8 ± 1.2%, 24.6 ± 3.9%, and 40.1 ± 3.7%, respectively, and the overall accuracy for abandoned cropland was 92.5% in the study conducted by He et al.74. It can be seen that the accuracy of the DCD method is comparable and even better than existing research methods, further proving that the method in this paper is suitable for large-scale studies.

Limitations of the current study

The proposed DCD method performs well in detecting abandoned cropland in Ukraine. However, there are several limitations and considerations regarding its applicability, as outlined below.

Time scale of targets

The DCD method proposed in this study aims to detect and segment the management patterns sequence of cropland, with the detection object’s temporal scale being annual. This limitation results in a lack of theoretical models and detection mechanisms for long-term unused cropland.

Under natural conditions, long-term unused cropland often undergoes a series of secondary succession from bare land to forests or grasslands over time39. If the initial period of long-term unused cropland falls within the detection range, the proposed method can only detect the starting year or the first few years of unused and classify them as unused cropland. Therefore, special attention should be given to continuous unused cropland in the detection results, as there is a high probability that they represent long-term unused cropland. However, if the initial period of long-term unused cropland is outside the detection range, there is a high probability that the proposed algorithm will classify such land as normal cultivated cropland.

Therefore, the detected abandoned cropland in Ukraine obtained using the DCD method proposed in this study only includes unused cropland and unattended cropland. This may lead to the possibility of underestimating the actual extent of abandoned cropland in Ukraine. For the detection of long-term unused cropland, a better solution would be to use the CCDC (Continuous Change Detection and Classification) algorithm to detect and segment different stages of cropland, as this approach can better describe and detect the sequences and characteristics of long-term unused cropland75.

Spatial scale of targets

The DCD method proposed in this study requires high time resolution remote sensing data due to its fine temporal scale. However, the existing data of this kind have relatively low spatial resolution, which limits the applicability of the proposed method in terms of spatial scale.

As shown in Fig. 11(C), although the detection results of the proposed method generally align with the shape of the land parcels, there are many jagged patterns along the boundaries. Overlaying the results with high-resolution imagery reveals that this is mainly caused by the low spatial resolution of the data. Ukrainian cropland has larger plot sizes compared to cropland in other regions of the world. Therefore, the proposed method exhibits higher accuracy and better performance in detecting abandoned cropland in Ukraine. However, if this method is applied to regions with a high degree of fragmented cropland, such as mountainous areas in China, the accuracy and performance of the detection will be significantly reduced. To apply this method to regions with a high degree of fragmented cropland, apart from employing strategies like cloud removal76,75,76,79and image fusion80,79,82, techniques such as mixed pixel decomposition83,84and super-resolution reconstruction85,86 offer potential to enhance the applicability at the spatial scale.

Conclusion

Firstly, this study obtained reliable temporal and spatial distribution information of abandoned cropland before and after the conflict in Ukraine (2015–2023). Through stratified random sampling and comparison with the visual interpretation results of medium and high resolution images, the accuracy is between 83 and 96%.

Secondly, a DCD method is proposed in this study. The region of interest identification module in the method accurately located the mature period of crops and divided them into growth and harvest periods, effectively improving the accuracy of abandoned cropland detection. The unused cropland detection module in the method could be used independently for unused cropland detection with high accuracy. This module only focused on the curves during the crop growth period, enhancing the efficiency of unused cropland detection. The self-supervised detection module in this method can effectively distinguish the two kinds of abandoned cropland, unused and unattended.

Finally, this study reveals the changes of abandoned cropland before and after the conflict in Ukraine. Through spatial visualization and analysis of abandoned cropland information in Ukraine from 2015 to 2023, it can be concluded that unused cropland in Ukraine during 2015–2021 was mainly distributed in the southern region, with approximately 138,000 hectares of cropland being unused for two or more consecutive years. In 2022, the unused cropland area was approximately double the average unused cropland area before the conflict, and it was widely distributed. Unattended cropland reached 462,000 hectares and was mainly concentrated in the eastern part of Ukraine. In 2023, compared to 2022, the unused cropland area decreased by 67.8%, while the unattended cropland area increased by 116.7%. Both types of abandoned cropland showed spatial clustering, with major clusters in the Crimea region, Kherson Oblast, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, and Donetsk Oblast.

For future research, in addition to further improving the DCD method, it would be beneficial to explore the driving factors of cropland abandonment in Ukraine87. This would help uncover the mechanisms between human factors and cropland abandonment, contributing to the development of a coupled model for the entire process of cropland abandonment in Ukraine and providing valuable insights for the study of abandoned cropland in other regions with similar characteristics.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GitHub with the URL: https://github.com/ZhangSK138/Classification-map-of-cropland-in-Ukraine.

References

Bengochea Paz, D., Henderson, K. & Loreau, M. Agricultural land use and the sustainability of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Model. 437, 109312 (2020).

Li, S. & Li, X. Global understanding of farmland abandonment: A review and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 27, 1123–1150 (2017).

Nega, W. & Balew, A. The relationship between land use land cover and land surface temperature using remote sensing: systematic reviews of studies globally over the past 5 years. Environ. Sci. & Pollut. Res. 29, 42493–42508 (2022).

Qianru, C. & Hualin, X. I. E. Research progress and discoveries related to cultivated land abandonment. J. Res. & Ecol. 12, 165–174 (2021).

Shengfa, L. I. & Xiubin, L. I. Progress and prospect on farmland abandonment. Acta Geogr. Sin. 71, 370–389 (2016).

Xiang, X. et al. Research progress and review of abandoned land based on citespace. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 42, 670–681 (2022).

Daskalova, G. N. & Kamp, J. Abandoning land transforms biodiversity. Science 380, 581–583 (2023).

Foley, J. A. et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 309, 570–574 (2005).

Li, Z. B., Zhang, Y. & Wang, M. Solar energy projects put food security at risk. Science 381, 740–741 (2023).

Campbell, J. et al. The global potential of bioenergy on abandoned agriculture lands. Environ. Sci. & technol. 42, 5791–5794 (2008).

Lenda, M. et al. Abandoned land: Linked to biological invasions. Science 381, 277 (2023).

Novara, A. et al. Agricultural land abandonment in Mediterranean environment provides ecosystem services via soil carbon sequestration. Sci. Total Environ. 576, 420–429 (2017).

Baumann, M. et al. Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy 28, 552–562 (2011).

Kuemmerle, T. et al. Post-Soviet farmland abandonment, forest recovery, and carbon sequestration in western Ukraine. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 1335–1349 (2011).

Smaliychuk, A. et al. Recultivation of abandoned agricultural lands in Ukraine: Patterns and drivers. Glob. Environ. Change 38, 70–81 (2016).

Behnassi, M. & El Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia-Ukraine war for global food security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 754–755 (2022).

Jagtap, S. et al. The Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Its Implications for the global food supply chains. Foods 11, 2098 (2022).

Nations U. A new United Nations report reveals the serious consequences of the war on Ukrainian society. 2024 UN News 2023

Olsen, V. M. et al. The impact of conflict-driven cropland abandonment on food insecurity in South Sudan revealed using satellite remote sensing. Nat. Food 2, 990–996 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. 2022 Spatiotemporal analysis and war impact assessment of agricultural land in Ukraine using RS and GIS technology. Land 11, 10 (1810).

Tollefson, J. What the war in Ukraine means for energy, climate and food. Nature 604, 232–233 (2022).

Chai, L. et al. Telecoupled impacts of the Russia Ukraine war on global cropland expansion and biodiversity. Nat. Sustain. 7(4), 432–441 (2024).

Estoque, R. C. et al. Scenario-based land abandonment projections: Method, application and implications. Sci. Total Environ. 692, 903–916 (2019).

Birong Z, Zhihua H, Ping D, et al. 2018 Abandoned Land Extraction Methods for Different Resolution Images. Geomatics & Spatial Information Technology. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-5867.2018.07.049 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Progress and prospects on information acquisition methods of abandoned farmland. Trans. Chinese Soc. Agric. Eng. (Transactions of the CSAE) 36, 258–268 (2020).

Dong, J. et al. State of the art and perspective of agricultural land use remote sensing information extraction. J. Geo-inf. Sci. 22(4), 772 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. The pattern of abandoned cropland and its productivity potential in China: A four-years continuous study. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161928 (2023).

Kolecka, N. et al. Mapping secondary forest succession on abandoned agricultural land with LiDAR point clouds and terrestrial photography. Remote Sens. 7, 8300–8322 (2015).

Lieskovský, J. et al. The abandonment of traditional agricultural landscape in Slovakia – Analysis of extent and driving forces. J. Rural Stud. 37, 75–84 (2015).

Yoon, H. & Kim, S. Detecting abandoned farmland using harmonic analysis and machine learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. & Remote Sens. 166, 201–212 (2020).

R V. Unsupervised ISODATA algorithm classification used in the landsat image for predicting the expansion of Salem urban, Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.17485/IJST/v13i16.271 (2020).

He, S. et al. Monitoring cropland abandonment in hilly areas with sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 timeseries. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14153806 (2022).

Song, W. Mapping cropland abandonment in mountainous areas using an annual land-use trajectory approach. Sustainability 11, 5951 (2019).

Zhu, X. et al. Mapping abandoned farmland in China using time series MODIS NDVI. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142651 (2021).

Liu, B. & Song, W. Mapping abandoned cropland using Within-Year Sentinel-2 time series. Catena https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.106924 (2023).

Yin, H. et al. Mapping agricultural land abandonment from spatial and temporal segmentation of Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 210, 12–24 (2018).

Yusoff, N. & Muharam, F. The Use of multi-temporal landsat imageries in detecting seasonal crop abandonment. Remote Sens. 7, 11974–11991 (2015).

Yusoff, N. M. et al. Phenology and classification of abandoned agricultural land based on ALOS-1 and 2 PALSAR multi-temporal measurements. Int. J. Digit. Earth 10, 155–174 (2016).

Xu, S. et al. Mapping cropland abandonment in mountainous areas in China using the google earth engine platform. Remote Sens. 15(4), 1145 (2023).

Alcantara, C. et al. Mapping the extent of abandoned farmland in Central and Eastern Europe using MODIS time series satellite data. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 035035 (2013).

Estel, S. et al. Mapping farmland abandonment and recultivation across Europe using MODIS NDVI time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 163, 312–325 (2015).

Löw, F. et al. Mapping cropland abandonment in the aral sea basin with MODIS time series. Remote Sens. 10(2), 159 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Reveal the severe spatial and temporal patterns of abandoned cropland in China over the past 30 years. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159591 (2023).

Bing Z, Youlongxu Z. INITIAL APPROACH ON EVALUATIONG TARGET AND APPLYING RESEARCH OF ARABLE LAND WASTING. journal of china agricultural resources and regional planning. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-9121.2003.05.014 (2003).

Xin-Yi C, Guo-Quan Z. Research progress on arable land abandonment in China and abroad. China Population,Resources and Environment. 28(S2), 37-41 (2018).

Zhu, Z. Change detection using landsat time series: A review of frequencies, preprocessing, algorithms, and applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. & Remote Sens. 130, 370–384 (2017).

USDA. Crop Calendars for Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus. https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/rssiws/al/crop_calendar/umb.aspx (2024).

Bentley, A. R. Broken bread — avert global wheat crisis caused by invasion of Ukraine. Nature 603, 551 (2022).

The war in Ukraine is exposing gaps in the world’s food-systems research. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00994-8 (2022).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Kong, D. et al. phenofit: An R package for extracting vegetation phenology from time series remote sensing. Methods Ecol. & Evol. 13, 1508–1527 (2022).

Shen, M. et al. No evidence of continuously advanced green-up dates in the tibetan plateau over the last decade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, E2329–E2329 (2013).

Zhang, X., Friedl, M. A. & Schaaf, C. B. Global vegetation phenology from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS): Evaluation of global patterns and comparison with in situ measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JG000217 (2006).

Zhang, X. Reconstruction of a complete global time series of daily vegetation index trajectory from long-term AVHRR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 156, 457–472 (2015).

Kong, D. et al. A robust method for reconstructing global MODIS EVI time series on the Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. & Remote Sens. 155, 13–24 (2019).

Kong, D. et al. Photoperiod explains the asynchronization between vegetation carbon phenology and vegetation greenness phenology. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JG005636 (2020).

Cleveland, W. S. robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 74, 829–836 (1979).

Chen, J. et al. A simple method for reconstructing a high-quality NDVI time-series data set based on the Savitzky-Golay filter. Remote Sens. Environ. 91, 332–344 (2004).

Yang, G. et al. A moving weighted harmonic analysis method for reconstructing high-quality SPOT VEGETATION NDVI time-series data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. & Remote Sens. 53, 6008–6021 (2015).

Cao, R. et al. A simple method to improve the quality of NDVI time-series data by integrating spatiotemporal information with the Savitzky-Golay filter. Remote Sen. Environ. 217, 244–257 (2018).

Bush, E. R. et al. Fourier analysis to detect phenological cycles using long-term tropical field data and simulations. Methods Ecol. & Evol. 8, 530–540 (2017).

Atzberger, C. & Eilers, P. H. C. Evaluating the effectiveness of smoothing algorithms in the absence of ground reference measurements. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 3689–3709 (2011).

Holben, B. N. Characteristics of maximum-value composite images from temporal AVHRR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 7, 1417–1434 (1986).

Jonsson, P. & Eklundh, L. Seasonality extraction by function fitting to time-series of satellite sensor data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. & Remote Sens. 40, 1824–1832 (2002).

Wallace, C. S. A. et al. Fallow-land Algorithm based on Neighborhood and Temporal Anomalies (FANTA) to map planted versus fallowed croplands using MODIS data to assist in drought studies leading to water and food security assessments. GISci. & Remote Sens. 54, 258–282 (2017).

Dara, A. et al. Mapping the timing of cropland abandonment and recultivation in northern Kazakhstan using annual Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 213, 49–60 (2018).

Hou, Z. et al. War city profiles drawn from satellite images. Nat. Cities https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00060-6 (2024).

Olofsson, P. et al. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 148, 42–57 (2014).

Huang, C. et al. Dynamics of national forests assessed using the landsat record: Case studies in eastern United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, 1430–1442 (2009).

Zhang, M. et al. Continuous detection of surface-mining footprint in copper mine using google earth engine. Remote Sens. 13, 4273 (2021).

Skakun, S. et al. Satellite Data Reveal cropland losses in South-Eastern Ukraine under military conflict. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00305 (2019).

Qadir, A. et al. Estimation of sunflower planted areas in Ukraine during full-scale Russian invasion: Insights from Sentinel-1 SAR data. Sci. Remote Sens. 10, 100139 (2024).

Deininger, K. et al. Quantifying war-induced crop losses in Ukraine in near real time to strengthen local and global food security. Food Policy 115, 102418 (2023).

He, T. et al. Quantitative analysis of abandonment and grain production loss under armed conflict in Ukraine. J. Clean. Prod. 412, 137367 (2023).

Pasquarella, V. J. et al. Demystifying landtrendr and CCDC temporal segmentation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. & Geoinf. 110, 102806 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. A review of cloud detection and thick cloud removal in medium resolution remote sensing images. Remote Sens. Technol. 7 Appl. 38, 143–155 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Thick cloud removal in multitemporal remote sensing images via low-rank regularized self-supervised network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. & Remote Sens. 62, 1–13 (2024).

Mahajan, S. & Fataniya, B. Cloud detection methodologies: variants and development—a review. Complex & Intell. Syst. 6, 251–261 (2020).

Meraner, A. et al. Cloud removal in Sentinel-2 imagery using a deep residual neural network and SAR-optical data fusion. ISPRS J. Photogramm. & Remote Sens. 166, 333–346 (2020).

Gao, F. et al. Toward mapping crop progress at field scales through fusion of landsat and MODIS imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 188, 9–25 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Online fusion of multi-resolution multispectral images with weakly supervised temporal dynamics. ISPRS J. Photogramm. & Remote Sens. 196, 471–489 (2023).

Sisheber, B. et al. Tracking crop phenology in a highly dynamic landscape with knowledge-based Landsat–MODIS data fusion. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. & Geoinf. 106, 102670 (2022).

Huang Z, Xie S. Mixed Pixel Decomposition Based On Improved N-FINDR Algorithm 2022 14th International Conference on Measuring Technology and Mechatronics Automation (ICMTMA) 2022 1081–1084

Kaur, S. et al. Mixed pixel decomposition based on extended fuzzy clustering for single spectral value remote sensing images. J Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 47, 427–437 (2019).

Niu X. 2018 An Overview of Image Super-Resolution Reconstruction Algorithm. 2018 11th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID). 16–18

Yu, M. et al. A review of single image super-resolution reconstruction based on deep learning. Multimed. Tools & Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-17660-4 (2023).

Levers, C. et al. Spatial variation in determinants of agricultural land abandonment in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 95–111 (2018).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Major Project, solicited by the National Office of Philosophy and Social Science, under the title of Interdisciplinary Research on the Theory and Methodology of Geo-environmental Analysis in the Era of Big Data (No. 20&ZD138).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made valuable contributions to this paper. Conceptualization, S.Z. and Y.Z.; resources, S.Z., Y.Z. and X.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z., X.Z. and J.L.; methodology, S.Z. and C.M.; data curation, S.Z., X.Z. and S.L.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z., Y.Z., C.M., and X.Z.; visualization, S.Z., Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z., Y.Z. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.Z., Y.Z. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X. et al. Revealing the distribution and change of abandoned cropland in Ukraine based on dual period change detection method. Sci Rep 15, 5765 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89556-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89556-2