Abstract

This retrospective study aims to evaluate the short-term efficacy and safety of brolucizumab every 6 weeks induction therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) cases. This study included 140 eyes from 140 patients (101 males and 39 females, with a mean age of 77.7 ± 8.7 years) with nAMD who received brolucizumab injections every 6 weeks as part of induction therapy across four participating centers between June 2020 and March 2024. Follow-up lasted for at least 20–24 weeks. Data collected included age, sex, history of nAMD treatment, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), central retinal thickness (CRT), presence or absence of exudation, and occurrence of intraocular inflammation (IOI). Sixty-one eyes had prior nAMD treatment. Mean BCVA (logMAR) was 0.40 ± 0.43 before brolucizumab therapy, improving to 0.38 ± 0.42, 0.33 ± 0.41, and 0.34 ± 0.44 after the first, second, and third injections, respectively. Significant improvements in BCVA were observed from the second injection onward (p < 0.05). CRT decreased significantly from baseline of 341.6 ± 151.0 to 219.1 ± 119.8, 204.0 ± 112.9, and 200.8 ± 96.0 after the first, second, and third injections, respectively (p < 1.0 × 10–20). Exudative findings, present in all cases before treatment, resolved in 64.3%, 82.1%, and 79.3% of cases after the first, second, and third injections, respectively. IOI was observed in five, three, and four eyes after the first, second, and third injections, respectively, accounting for 8.6% of all cases. No cases had retinal vasculitis or occlusion. In conclusion, brolucizumab administered every 6 weeks as induction therapy for nAMD showed favorable efficacy and safety outcomes during a 6-month follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the leading sight-threatening diseases in developed countries1,2. Besides causing significant visual impairment, AMD often leads to severe psychological distress and negatively affects the quality of life3. The widely used classification of AMD divides it into early and intermediate stages based on drusen size and abnormalities in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)4,5. Advanced AMD is further divided into atrophic AMD (dry AMD) and neovascular AMD (wet AMD)5. Neovascular AMD (nAMD) is subcategorized into type 1, type 2, and type 3 macular neovascularization (MNV) as determined by fluorescein angiography (FA), indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), and optical coherence tomography (OCT)6,7,8. The MNV is primarily caused by overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)9,10.

Intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents are the first-line treatment for nAMD, significantly improving visual prognosis and reducing the risk of legal blindness11. For over a decade, ranibizumab and aflibercept have been the most commonly used anti-VEGF agents for nAMD treatment12,13. Although these agents demonstrated initial improvements in visual function, maintaining long-term visual outcomes remains a challenge in clinical practice. The pro re nata (PRN) regimen, which involves administering additional treatments after the recurrence of exudative lesions, has been insufficient for sustaining long-term vision14,15. Consequently, the treat-and-extend (TAE) regimen, which extends treatment intervals following an initial loading phase, has become the preferred approach to maintaining vision over time16,17. However, some patients remain refractory to ranibizumab and aflibercept or require frequent injections, underscoring the need for more effective and longer-lasting therapeutic options for nAMD18,19,20.

Brolucizumab is a humanized single-chain variable fragment that inhibits VEGF-A and has been approved for treating nAMD in the United States, Europe, and Asia21,22,23,24,25. The HAWK and HARRIER studies demonstrated that intravitreal brolucizumab (IVBr) effectively improved and maintained visual acuity for 2 years, with outcomes comparable to those of intravitreal aflibercept (IVA)23. Moreover, IVBr provided better control of intraretinal, subretinal, and sub-RPE fluid than IVA22,23. Accordingly, brolucizumab has the potential to be an effective treatment for nAMD refractory to ranibizumab and aflibercept26,27,28. However, intraocular inflammation (IOI), including retinal vasculitis (RV) and retinal vascular occlusion (RO), has emerged as a considerable complication of IVBr compared to other anti-VEGF agents22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Interestingly, most IOI events occur within the first 3–6 months of initiating IVBr therapy29,30,31. Although the underlying mechanisms leading to IVBr-associated IOI remain poorly understood, the recommended induction protocol—three brolucizumab injections every 4 weeks—has raised concerns regarding its potential role in IOI development possibly associated with oversuppression of VEGF. A phase 1/2 study of brolucizumab for nAMD demonstrated that a single dose of 6.0 mg brolucizumab which is the same dose in commercial use achieved the maximum visual and anatomical effects 6 weeks after the injection with no report of IOI21. In addition, KESTREL and KITE trials for diabetic macular edema (DME) conducted five loading doses of 6.0 mg brolucizumab every 6 weeks as an induction therapy reported a lower incidence of IOI, RV, and RO compared to those in the clinical trials for nAMD36. Since no report has demonstrated the benefit and risk of every 6-week induction therapy of brolucizumab for nAMD to date, we considered evaluating the outcomes of this induction regimen.

This study aimed to retrospectively evaluate the 6-month outcomes of IVBr administered using an alternative induction regimen of injections every 6 weeks for patients with nAMD.

Results

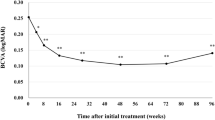

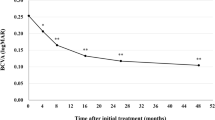

The baseline characteristics of the patients recruited in this study are presented in Table 1. The cohort comprised 101 males (72.1%) and 39 females (27.9%), with a mean age of 77.7 ± 8.7 years. Among the patients, 73 received IVBr in the right eye and 67 in the left eye; in cases of bilateral treatment (three patients), only the data for the right eye were analyzed. Sixty-one eyes (43.6%) had prior treatment for nAMD by another anti-VEGF, photodynamic therapy (PDT), or a combination of both. The mean best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) (minimum angle of resolution: logMAR) was 0.40 ± 0.43. After the first, second, and third IVBr injections, BCVA improved to 0.38 ± 0.42, 0.33 ± 0.41, and 0.34 ± 0.44, respectively. Statistically significant improvements were observed from the second injection onward (p = 0.12, 0.0018, 0.022, respectively, compared to the baseline) (Fig. 1). The mean baseline central retinal thickness (CRT) was 341.6 ± 151.0. CRT significantly decreased from 219.1 ± 119.8, 204.0 ± 112.9, and 200.8 ± 96.0 after the first, second, and third injections, respectively (p = 8.8 × 10–23, 1.3 × 10–22, 4.1 × 10–21, respectively, compared to the baseline) (Fig. 2). Exudative findings, present in all cases at baseline, resolved in 64.3%, 82.1%, and 79.3% of eyes after the first, second, and third injections, respectively. These changes were statistically significant (p = 5.1 × 10–37, 5.6 × 10–54, 7.8 × 10–51, respectively, compared to the baseline) (Fig. 3).

New IOI was observed in five, three, and four eyes after the first, second, and third IVBr injections, respectively, accounting for 8.6% of the total cases. No cases had RV or RO during the follow-up period (Table 2). The incidence of IOI did not differ significantly between the sexes (7.9% in males and 10.3% in females, p = 0.74). When compared to our previous multicenter study including 1,351 Japanese patients with nAMD treated with IVBr31, in which most cases were supposed to receive 3 IVBr every 4 weeks as induction therapy, the incidence of IOI in the study (10.3% within 6 months of the first injection) was not statistically different from that in our study (p = 0.66 with chi-square test). However, the incidence of RV and/or RO was significantly lower in the present study (0.0%) than in the previous study (3.9%) (p = 0.0075 with Fisher’s exact test). In our study, two cases showed vision loss of more than 0.3 logMAR, equivalent to a loss of 15 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters at the onset of IOI. These cases were treated with or without corticosteroids (applied via topical, oral, or sub-Tenon injection). The final BCVA after resolving IOI was not determined during the follow-up period in this study.

Discussion

We investigated the short-term outcomes of IVBr administered every 6 weeks as an induction therapy for nAMD and demonstrated a favorable benefit-to-risk profile with this regimen.

In randomized clinical trials, IVBr showed superiority over IVA in controlling intraretinal, subretinal, and sub-RPE fluid in treatment-naïve nAMD cases22,23. Some following clinical studies with real-world settings also showed favorable visual and anatomical outcomes of IVBr for nAMD24,25,26,27,28. However, brolucizumab is not the first choice anti-VEGF agent for nAMD in Japan and other countries because many physicians are concerned about the possible risk of IOIs associated with brolucizumab29,30,31,32,33,34,35. In the KESTREL and KITE trials for DME, five loading doses of brolucizumab were administered every 6 weeks as an induction therapy36. These studies reported IOI, RV, and RO incidences of 3.7, 0.5, and 0.5%, respectively, for brolucizumab 6 mg, compared to 0.5, 0, and 0% with aflibercept 2 mg in the KESTREL study. In the KITE study, the respective incidences in both the brolucizumab 6 mg and aflibercept 2 mg groups were 1.7, 0, and 0.6%. Despite the different pathogenesis between nAMD and DME, we speculated that the higher incidence of IOI with IVBr (IOI, RV, and RO were 4.6, 3.3, and 2.1%, respectively in pooled brolucizumab arms vs. 1.1% IOI in pooled aflibercept arms of 2 studies) found in HAWK and HARRIER studies29 attributed to every 4 weeks IVBr in the induction therapy. Based on these findings, we investigated nAMD cases treated with IVBr administered every 6 weeks during the induction phase. However, this approach may constitute undertreatment for nAMD despite a previous study reporting that a single dose of 6.0 mg brolucizumab achieved the maximum visual and anatomical effects 6 weeks after the injection in nAMD cases.21 In this study, the mean BCVA showed significant improvement after the second IVBr injection, with an overall improvement of 0.06 logMAR (equivalent to three ETDRS letters) after the third injection. Matsumoto et al. reported that a 3-monthly IVBr induction therapy for consecutive treatment-naïve nAMD patients significantly improved the mean BCVA, with values rising from 0.25 ± 0.30 logMAR at baseline to 0.21 ± 0.28 (P < 0.05) at week 4 and 0.13 ± 0.28 (P < 0.01) at week 1625. In comparison, the mean baseline BCVA in our study was worse, and the vision gain after initiating IVBr was less pronounced. This difference is likely due to the inclusion of cases refractory to other anti-VEGF agents in our study, which may have represented more severe disease than in the Matsumoto et al. study. Furthermore, the participants in our study were a non-consecutive case series, in which physicians opted for brolucizumab due to its potentially stronger anti-VEGF effect than other agents, suggesting that more aggressive cases were included. Several reports have also shown a modest improvement in mean BCVA in nAMD cases when switching to brolucizumab from other anti-VEGF agents.26,27,28 In contrast, the mean CRT and dry macula ratio were significantly improved after the first IVBr injection, indicating good anatomical outcomes with brolucizumab administered every 6 weeks during the induction therapy.

The incidence of any IOIs in our study was relatively lower, though not significant, than the previous reports in Japanese patients with nAMD treated with IVBr.27,28,29,30 Several studies have suggested a higher incidence of IOI in East Asian populations, although the reasons for this remain unknown. A multicenter retrospective study of 294 eyes from Korean patients with nAMD reported an IOI incidence of 13.9%37. In contrast, the incidence of RV and/or RO in our study was significantly lower than in a previous multicenter study of Japanese patients with nAMD treated with IVBr.31 It was also significantly lower than that of another multicenter study of Japanese nAMD patients treated with IVBr every 4-week induction (4 RV/RO cases out of 127 cases enrolled, p < 0.05)30. This suggests that the every 6-week induction regimen of brolucizumab may help reduce the risk of RV/RO associated with IVBr. However, brolucizumab-associated IOIs (including RV/RO) may occur after the first injection in treatment-naïve cases, which suggests that some of IOIs may not involve an immune reaction. A previous report suggested that an oversuppression of VEGF may be harmful to the retinal vasculature38. We speculate that an oversuppression of VEGF with brolucizumab might damage retinal vessels, which could be associated with IOI, RV and RO without involving an immune reaction in certain cases. Extending the injection interval in the induction phase may reduce the chance of VEGF oversuppression. Anyhow, close monitoring of patients after each IVBr injection is essential, and they should be advised to promptly contact their ophthalmologist if they notice any abnormal visual symptoms34. A recent report described that most IOIs were manageable with or without corticosteroids, and patients typically showed a relatively good prognosis when treated early35.

The limitations of this study were the relatively small sample size and the retrospective study design, which might have been affected by undefined confounding factors or population-based biases. Replication studies in other cohorts are required to make a robust conclusion. Moreover, a systematic prospective study with a larger sample size may warrant the results of this study. In addition, we did not perform FA to evaluate RV/RO in all IOI cases, which might have led to an underestimation of the incidence of RV/RO.

In summary, this study demonstrated that brolucizumab with a 6-week induction therapy for nAMD showed favorable efficacy and safety profile over 20–24 weeks of follow-up. Although further evaluation is necessary, a 6-week induction interval could be considered as a treatment option when treating nAMD patients with brolucizumab.

Methods

Study participants

A retrospective study was conducted on a non-consecutive case series of nAMD treated with brolucizumab using a 6-week induction therapy regimen. The study included cases from four participating centers, including Osaka Metropolitan University, Yokohama City University Medical Center, Kansai Medical University Medical Center, and Hyogo Medical University, between June 2020 and March 2024. Patients were followed for a minimum of 20–24 weeks. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the approval for the pooled analysis was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2024-049, approval date: May 24, 2024). Ethics approval was subsequently secured at each participating center. Informed consent was obtained by an opt-out indicated to the patients before the study.

Procedure

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Japanese ethnicity, (2) age 50 years or more, (3) a definite diagnosis of nAMD, and (4) patients who had received at least one IVBr injection and were scheduled for three IVBr every 6 weeks as induction therapy. At the initial visit, all patients underwent a comprehensive examination, including BCVA measurement using a Landolt C chart, fundus examination with slit-lamp microscopy, standard or wide-field FA (at the discretion of the acting physician and depending on the availability at the participating institution), IA, and OCT to diagnose nAMD. OCT angiography was used when MNV was suspected and undetectable by other examinations. Following the induction phase, patients transitioned to a TAE regimen, with injection intervals starting from 8–12 weeks, based on achieving a "dry macula." A dry macula was defined as the absence of intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid, retinal hemorrhage, or subretinal hemorrhage. The state of retinal pigment epithelial detachment was not included in the criteria for defining a dry macula. IOI was diagnosed if any cells were detected in the anterior chamber and/or vitreous cavity or if vitreous opacity was observed at any time point after administrating IVBr. Additional FA was considered if there were any signs of RV/RO during the fundus examination. Patients were excluded if they received one or more prophylactic treatments for IOI, including topical administration of corticosteroids32.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures were BCVA changes and IOI, RV, and RO incidence. Other outcome measures in this study were the participants’ age, sex, history of nAMD treatment, CRT, and dry macula ratio. For patients who received bilateral IVBr treatment, only the right eye was included in the analysis. These measures were evaluated at baseline and during follow-up visits at 6, 12, and 20–24 weeks, corresponding to the visits after the first, second, and third IVBr injection, respectively. BCVA was assessed using a Landolt C chart and converted to the logMAR units before analyses.

Statistical analysis

A paired-t test was used to compare BCVA and CRT before and after the treatment. Fisher’s exact test was utilized to compare the dry macula ratio before and after starting IVBr. A chi-square test was used to assess the incidence of IOI between sexes. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [SH], upon reasonable request.

References

Klein, R. et al. Fifteen-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 114, 253–262 (2007).

Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2, e106–e116 (2014).

Honda, S. et al. Impact of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: burden of patients receiving therapies in Japan. Sci. Rep. 11, 13152 (2021).

Abdelsalam, A., Del Priore, L. & Zarbin, M. A. Drusen in age-related macular degeneration: pathogenesis, natural course, and laser photocoagulation-induced regression. Surv. Ophthalmol. 44, 1–29 (1999).

Ferris FL, et al. Age-related eye disease study (AREDS) research group. A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 123, 1570–1574 (2005)

Spaide, R. F. et al. Consensus nomenclature for reporting neovascular age-related macular degeneration data: Consensus on neovascular age-related macular degeneration nomenclature study group. Ophthalmology 127, 616–636 (2020) (Erratum in: Ophthalmology. 127, 1434–1435 (2020)).

Faatz, H. et al. Vascular analysis of type 1, 2, and 3 macular neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography shows new insights into differences of pathologic vasculature and may lead to a more personalized understanding. Biomedicines 10, 694 (2022).

Izquierdo-Serra, J. et al. Writing committee of the fight retinal blindness spain (FRB! Spain) users group. Macular neovascularization type influence on anti-vegf intravitreal therapy outcomes in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 8, 350–359 (2024).

Ambati, J. & Fowler, B. J. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron. 75, 26–39 (2012).

van Lookeren, C. M., LeCouter, J., Yaspan, B. L. & Ye, W. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration and therapeutic opportunities. J. Pathol. 232, 151–164 (2014).

Bloch, S. B., Larsen, M. & Munch, I. C. Incidence of legal blindness from age-related macular degeneration in Denmark: Year 2000 to 2010. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 153, 209–213 (2012).

Brown, D. M. et al. ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: Two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology 116, 57-65.e5 (2009).

Heier, J. S. et al. VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 Study Groups. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 119, 2537–2548 (2012).

Rofagha, S., Bhisitkul, R. B., Boyer, D. S., Sadda, S. R. & Zhang, K. SEVEN-UP study group. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: A multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 120, 2292–2299 (2013).

Holz, F. G. et al. Multi-country real-life experience of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 99, 220–226 (2015).

Freund, K. B. et al. Treat-and-extend regimens with anti-vegf agents in retinal diseases: A literature review and consensus recommendations. Retina. 35, 1489–1506 (2015).

Ohji, M. et al. ALTAIR Investigators. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept treat-and-extend regimens in exudative age-related macular degeneration: 52- and 96-week findings from ALTAIR: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Ther. 37, 1173–1187 (2020).

Doguizi, S., Ozdek, S. & Yuksel, S. Tachyphylaxis during ranibizumab treatment of exudative age-related macular degeneration. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 8, 846–848 (2015).

Yang, S., Zhao, J. & Sun, X. Resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A comprehensive review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 10, 1857–1867 (2016).

Hara, C. et al. Tachyphylaxis during treatment of exudative age-related macular degeneration with aflibercept. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 257, 2559–2569 (2019).

Holz, F. G. et al. Single-chain antibody fragment VEGF inhibitor RTH258 for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A randomized controlled study. Ophthalmology 123, 1080–1089 (2016).

Dugel, P. U. et al. HAWK and HARRIER study investigators. HAWK and HARRIER: Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-masked trials of brolucizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 127, 72–84 (2020).

Dugel, P. U. et al. 2021 HAWK and HARRIER: Ninety-six-week outcomes from the phase 3 trials of brolucizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 128, 89–99 (2021) (Erratum in: Ophthalmology. 129, 593–596 (2022)).

Tanaka, K. et al. Short-term results for brolucizumab in treatment-naïve neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a Japanese multicenter study. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 66, 379–385 (2022).

Matsumoto, H., Hoshino, J., Mukai, R., Nakamura, K. & Akiyama, H. One-year results of treat-and-extend regimen with intravitreal brolucizumab for treatment-naïve neovascular age-related macular degeneration with type 1 macular neovascularization. Sci. Rep. 12, 8195 (2022).

Ueda-Consolvo, T. et al. Switching to brolucizumab from aflibercept in age-related macular degeneration with type 1 macular neovascularization and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: an 18-month follow-up study. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 261, 345–352 (2023).

Coney, J. M. et al. Switching to brolucizumab: injection intervals and visual, anatomical and safety outcomes at 12 and 18 months in real-world eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Int. J. Retina Vitreous. 9, 8 (2023).

Hirayama, K. et al. Switching to intravitreal brolucizumab after ranibizumab or aflibercept using treat and extend regimen for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Japanese patients: 1-Year results and factors associated with treatment responsiveness. J Clin Med. 13, 4375 (2024).

Monés, J. et al. Risk of inflammation, retinal vasculitis, and retinal occlusion-related events with Brolucizumab: Post Hoc Review of HAWK and HARRIER. Ophthalmology 128, 1050–1059 (2021).

Maruko, I. et al. Japan AMD Research Consortium. Brolucizumab-related intraocular inflammation in Japanese patients with age-related macular degeneration: A short-term multicenter study. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259, 2857–2859 (2021).

Inoda, S. et al. Incidence and risk factors of intraocular inflammation after brolucizumab treatment in Japan: A multicenter age-related macular degeneration study. Retina 44, 714–722 (2024).

Kataoka, K. et al. Three cases of brolucizumab-associated retinal vasculitis treated with systemic and local steroid therapy. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 65, 199–207 (2021).

Hikichi, T. Three Japanese cases of intraocular inflammation after intravitreal brolucizumab injections in one clinic. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 65, 208–214 (2021).

Baumal, C. R. et al. Expert opinion on management of intraocular inflammation, retinal vasculitis, and vascular occlusion after brolucizumab treatment. Ophthalmol Retina. 5, 519–527 (2021).

Hirono, K., Maruyama-Inoue, M., Yanagi, Y. & Kadonosono, K. Visual outcomes of intraocular inflammation after brolucizumab injection in Japanese patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 19, e0302295 (2024).

Brown, D. M. et al. KESTREL and KITE: 52-week results from two phase iii pivotal trials of brolucizumab for diabetic macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 238, 157–172 (2022).

Kim, D. J. et al. Short-term safety and efficacy of intravitreal brolucizumab injections for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A multicenter retrospective real-world study. Ophthalmologica 246, 192–202 (2023).

Lu, M. & Adamis, A. P. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene regulation and action in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 15, 69–79 (2002).

Funding

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) – No. 22 K09773. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: SH, Study execution: MMI, TO, AK, YK, and YY, Data analysis and interpretation: SH, Writing the manuscript draft: SH, Revision of the manuscript: MMI, TO, FG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Honda, S., Maruyama-Inoue, M., Otsuji, T. et al. Efficacy and safety of brolucizumab every 6 weeks induction therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep 15, 5705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89638-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89638-1