Abstract

The elasto-plastic dynamic response of tunnels surrounded by frozen soil under loads applied to the tunnel invert is investigated in this study. Special attention is paid to the frozen soil in plastic zones around the tunnel in cold regions where anisotropic frost heave occurs. Analytical solutions of displacement and stress distributions in the lining, plastic zone of frozen soil, elastic zone of frozen soil, and unfrozen soil layer under load are derived. Unknown parameters are determined by satisfying continuity and boundary conditions between contact surfaces of different media. The parametric analysis reveals that the radial and circumferential stresses experience the most significant decrease in the plastic zone and at the contact surfaces of different media. The thickness of the frozen soil layer, along with the development of its plastic zone, influences the dynamic response of the frozen soil around the tunnel. Furthermore, variations in soil and lining parameters also have an impact on stress and displacement distributions in each medium. The findings of this study aim to provide valuable insights for the numerical simulation, design, and construction of future tunnels in cold regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China has implemented policies for economic development, such as “The Belt and Road Initiative” and “the New Silk Road,” which have connected numerous countries across Asia, Europe, and Africa. In order to further promote economic growth and cultural exchanges, it is crucial to continuously improve basic transportation facilities and upgrade technology. Various projects including the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, the China-Russia Oil Pipeline, the Lanzhou-Xingjiang High-Speed Railway, the Sichuan-Tibet Highway, and the Sichuan-Tibet Railway have been undertaken in China1. Among these infrastructure projects, the construction of tunnels has emerged as a crucial strategy to improve transportation and optimize routes. However, a significant challenge arises when these tunnels need to traverse large areas of permafrost or seasonally frozen ground. Permafrost and seasonally frozen ground cover approximately 50% of the Earth’s land area, with significant concentrations in Russia, Canada, China, the United States, and Northern Europe2,3,4. China, as the third-largest permafrost country, possesses a vast permafrost area of 1.591 km2, accounting for 15.8% of its land area, in addition to a seasonally frozen ground of about 5.361 km2, accounting for 53.5% of the country’s total area5. Permafrost is a critical component of the cryosphere and exhibits high sensitivity to global climate change and human activities6, with a unique geological formation shaped by geological history and climate change, making it highly influenced by regional geography, tectonics, lithology, hydrological conditions, and vegetation characteristics7. Permafrost is characterized by a heterogeneous microstructure comprising various minerals, as well as pores, pore ice, and ice lenses. These microstructural elements significantly impact the mechanical behavior and damage process of permafrost at a macroscopic level8, consequently affecting the maintenance and utilization of infrastructure9. When the temperature drops below freezing, water freezes, and soil particles bind together through ice crystals, resulting in a soil-ice mixture. The cohesion at the soil-ice interface enhances the microstructural strength of permafrost, while the size of soil particles influences this cohesion and ultimately affects the macroscopic deformation behavior10. Therefore, permafrost exhibits porous, ice-related, and particle-related properties11. The presence of ice alters the connectivity between phases in frozen soils, leading to mechanical properties that differ significantly from those of unfrozen soils. The phase change of frozen soil exacerbates soil instability as a foundation, mainly due to the highly temperature-sensitive mechanical properties of permafrost12.

The plastic zone in frozen soil surrounding tunnels is a critical factor in determining the stability of tunnels in cold regions. Tunnels surrounded by frozen soil are highly vulnerable to extreme environments. As the temperature fluctuates, the liquid phase in the soil freezes and expands, creating forces on the tunnel lining known as frost heave13. Zhou14 et al. pointed out that frost heave increases stress in the surrounding soil and leads to the formation of a plastic zone when the stress exceeds the yield stress. The development of the plastic zone in frozen soil compromises the stability of the tunnel structure. If the frost heave is significant enough, it can destroy the lining and further destabilize the tunnel. Thus, it is important to investigate the stress distribution and deformation in the plastic zone of the soil surrounding the tunnel in cold regions. Increasing the modulus of elasticity of frozen soil enhances the restraint on the frozen soil, resulting in greater frost heave and a higher likelihood of reaching a plastic state15. Additionally, the stress, modulus of elasticity, and shear modulus of the soil influence the development of the plastic zone by controlling the deformation. If changes in these parameters reduce the limiting deformation caused by frost heave, the plastic zone will expand. Besides, the angle of internal friction and shear modulus, which are connected to shear strength, are also affected, further impacting the plastic zone16. The thickness of frozen soil and the normal strain due to frost heave also control the deformation caused by frost heave, with increases in these parameters resulting in larger deformations and a wider range of the plastic zone17. Nearly half of the engineering problems and environmental disasters in cold regions are associated with frost heave18,19, which significantly affects the structural stability of tunneling projects and can even lead to accidents20. Finding effective measures to control engineering problems in cold regions is crucial for ensuring the stability, durability, and cost-effectiveness of frozen foundations18. Therefore, thermal insulation is one of the key and difficult point in the design and construction of tunnels in cold regions21,22. In recent years, active freeze-proof measures using solar energy, geothermal energy, electric energy, and wind energy as heat sources have developed rapidly, but have not yet been applied to engineering practice on a large scale. Among the various measures to prevent freezing and thawing problems affecting cold-region tunnels, heat preservation is still one of the most widely used and effective methods in engineering construction23,24.

Until now, the research on tunnels in cold regions primarily focuses on understanding the frost heave caused by climate change and implementing measures to mitigate it. Most of the existing studies of operational tunnels have used various models to describe the dynamic response of tunnels buried in unfrozen soil, including curved beams25,26, elastic shells27,28,29, Euler–Bernoulli beams30,31, and elastic or viscoelastic materials32. The theories widely accepted for describing the dynamic response of soil can be divided into elastic models, near-saturation models, Biot’s theory, and mixed theories33. Some studies have investigated the coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical dynamic response of tunnels lined with circular thin shells under the combined action of heat sources and external loads34. Others have expanded the tunnel lining model to three dimensions, considering it as an infinitely long thin cylindrical shell suitable for linear elastic, homogeneous, and isotropic materials35. Improved tunnel models have also been developed to evaluate dynamic stresses induced by trains in saturated soils, accounting for multiple moving loads, changes in the grouting layer, and pore water pressure36. Analytical solutions have been proposed for calculating vibrations of twin tunnels embedded in a half-space to assess the effect of adjacent tunnels on ground vibrations induced by underground railroads37. With more and more cold-region tunnels in operation, there has been increasing attention paid to the dynamic response of the tunnel buried in frozen soil38. Some studies have identified soil temperature and ice content as two key factors affecting the dynamic properties of frozen soil39. Zhang and Chen40 considered unsaturated frozen soil as a porous elastic medium with a moving point load acting on an infinitely long beam (tunnel lining), and analyzed the critical velocity of unsaturated frozen soil in cold regions under different degrees of saturation and ice content. Although some preliminary studies have been conducted on the dynamic response of tunnels in cold regions based on existing research and the theory of frozen soil41,42, further investigation is needed.

Therefore, the study of the plastic zone caused by freezing of the soil around tunnels in cold regions is of great importance and research in this area is increasing. However, the presence of a load acting on the lining adds complexity to the problem. Taking into account the inevitable vibrations caused by trains, a preliminary study on the impact of plastic zone in frozen soil on the dynamic response of cold-region tunnel systems is more practical for engineering purposes. In order to investigate the elasto-plastic dynamic response of frozen soils with frost heave around tunnels in cold regions, this study focuses on the dynamic response of the lining, plastic zone of frozen soil, elastic area of frozen soil, and unfrozen soil under load in the frequency domain. Analytical solutions for the displacements and stresses of the lining, plastic zone of frozen soil, elastic area of frozen soil, and unfrozen soil under load are derived. The unknown parameters are determined based on the continuity condition and boundary condition. Furthermore, this study discusses the effects of the anisotropic frost heave coefficient, external load, and thickness of the elastic area of frozen soil on the dynamic response of tunnels in cold regions, taking into consideration the development of plastic zone of frozen soil.

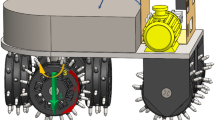

Governing equations for the cold-region tunnel system

The soils surrounding tunnels buried in cold regions are primarily composed of permafrost or seasonally frozen soils, which are highly susceptible to the effects of low temperatures. As a result, a portion of the soil may deteriorate. In order to address this issue, a simplified model of elasto-plastic dynamic response of the frozen soil surrounding the tunnel in cold regions has been developed (see Fig. 1). This model consists of several distinct zones, namely the lining Zone I, the plastic zone of frozen soil Zone II, the elastic zone of frozen soil Zone III, and the unfrozen soil Zone IV, arranged in order from the innermost to the outermost layer. R1, R2, R3, and R4 are the distances from the center of lining O to the inner surface of the tunnel lining, the contact surface between the lining and the plastic zone of frozen soil, the contact surface between the plastic zone of frozen soil and the elastic zone of frozen soil, and the frozen surface, respectively. \(d_{1} = R_{2} - R_{1}\), \(d_{2} = R_{3} - R_{2}\), and \(d_{3} = R_{4} - R_{3}\) represent the thickness of the lining, the thickness of the plastic zone of frozen soil, and the thickness of the elastic zone of frozen soil, respectively. The lining invert is subjected to a uniformly distributed load \(q_{0} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\), where ω is circular frequency, q0 is amplitude of the load, \({\text{i}}^{2} = - 1\), and t represents time. Additionally, \(\sigma_{{\text{f}}}\), \(\sigma_{{\text{p}}}\), \(\sigma_{{\text{u}}}\), and p0 are radial stresses between the lining and the plastic zone of frozen soil, between the plastic zone of frozen soil and the elastic zone of frozen soil, between the elastic zone of frozen soil and the unfrozen soil, and the initial ground stress, respectively. p0 can be expressed as the ground stress, and the model can be adjusted accordingly (see Fig. 1), where α is the vertical pressure coefficient related to the self-weight of the overlying soil. The subscripts L, u, and f are associated with the lining, plastic and elastic zones, respectively. The model proposed in this paper is based on the following assumptions:

-

(1)

The cross-section of tunnel is circular. The soil is treated as elasto-plastic media, and the lining is an elastic isotropic material.

-

(2)

The model is considered as a plane strain problem and the process of the frost heaving is not taken into account.

-

(3)

The effects of water migration and energy loss at the interface between two different media on dynamic response are ignored.

Governing equation of frozen soil

Considering the variation of temperature in the soil with freezing direction, the anisotropic frost heave coefficient of frozen soil during freezing can be approximated by the ratio of horizontal frost heaving strain to vertical frost heaving strain \(\left( {\alpha_{//} /\alpha_{ \bot } } \right)\) to the ratio of radial frost heaving strain to circumferential frost heaving strain \(\left( {\alpha_{r} /\alpha_{\theta } } \right)\)43. The relationship between volumetric frost heaving strain, anisotropic frost heave coefficient k, radial frost heaving strain, and circumferential frost heaving strain of frozen soil around a tunnel in cold regions can be expressed as \(\alpha_{r} = k\varepsilon_{{\text{v}}} /\left( {k + 2} \right)\) and \(\alpha_{\theta } = \varepsilon_{{\text{v}}} /\left( {k + 2} \right)\).

To solve the problems related to the elasto-plastic dynamic response of a tunnel in cold regions surrounded by frozen soil experiencing frost heave, the tunnel’s cross-section is assumed to be circular, and the problem is considered as a plane strain problem. The lining is considered as an isotropic elastic material, and the frozen soil is considered as an ideal elasto-plastic material.

The strains of the frozen soil in the plastic zone satisfy the following compatibility equation

where \(\varepsilon_{r}\) and \(\varepsilon_{\theta }\) are radial and circumferential strains of the frozen soil, respectively. r is the radius.

Based on the plastic flow rule and the Mohr–Coulomb criterion commonly used for geomaterials, the linear relationship between the change in volume of the frozen soil in the plastic zone and the change in axial strain under axisymmetric conditions satisfies44

where \(\psi\) = dilatancy angle. \(\varepsilon_{r}^{{\text{p}}}\) and \(\varepsilon_{{\text{v}}}^{{\text{p}}}\) represent the radial strain and volumetric strain of the frozen soil in plastic zone.

Meanwhile, the volumetric strain could be given by

where \(\varepsilon_{\theta }^{{\text{p}}}\) is the circumferential strain of frozen soil in the plastic zone.

Therefore, Eq. (2) can be simplified as

The distortion of Eq. (4) yields

where \(\beta_{{\text{f}}} = \frac{1 + \sin \psi }{{1 - \sin \psi }}\).

The strains in the plastic zone take the following forms

in which \(\varepsilon_{r}^{{\text{e}}}\) and \(\varepsilon_{\theta }^{{\text{e}}}\) are radial and circumferential strains of the frozen soil in the elastic zone, respectively.

Then, substituting Eqs. (5)–(7) into Eq. (1) yields

The equation of motion for the frozen soil in the plastic zone can be expressed as

where \(\sigma_{r}^{{{\text{II}}}}\) and \(\sigma_{\theta }^{{{\text{II}}}}\) are the radial and circumferential stresses of the frozen soil in the plastic zone, respectively; \(u_{r}^{{{\text{II}}}}\) is the radial displacement of the frozen soil in the plastic zone.

For frozen soils in the plastic zone, the following geometrical conditions need to be met

Based on the theory of anisotropic frost heave and elasticity of frozen soil, the constitutive equations for the frozen soil in the elastic zone take the following forms45

in which Ef and \(\nu_{{\text{f}}}\) represent Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the frozen soil, respectively. The relationship between Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus of frozen soil \(\mu_{{\text{f}}}\) can be obtained by \(\mu_{{\text{f}}} = {{E_{{\text{f}}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{E_{{\text{f}}} } {2(\nu_{{\text{f}}} + 1)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {2(\nu_{{\text{f}}} + 1)}}\).

For steady state vibration, we set \(u_{r}^{{{\text{II}}}} = R_{1} U_{\eta }^{{{\text{II}}}} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\), \(U_{\eta }^{{{\text{II}}}}\) represents the dimensionless radial displacement of the frozen soil in the elastic zone. To facilitate calculations, the following dimensionless quantities are introduced

The dimensionless form of Eqs. (10) and (11) could be rewritten

Furthermore, substituting Eqs. (15) and (16) into Eq. (8) yields

And the solution to Eq. (17) takes the following form

where B1 is the unknown parameter to be determined.

Substituting Eq. (18) into Eq. (5) yields

Then, by substituting Eqs. (44), (45), (47), and (48) into Eqs. (6) and (7), the strain of the frozen soil in the plastic zone can be obtained

By substituting Eqs. (6), (7), (20), and (21) into Eqs. (12) and (13), the stresses of the frozen soil in the plastic zone can be obtained

where \(\upsilon_{1} = \left( {2\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)\left( {\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)\eta\); \(\upsilon_{2} = h_{3} \left( {\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)^{2} \eta^{2}\); and \(\upsilon_{3} = h_{3} \left( {\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)\nu_{{\text{f}}} \eta^{2}\).

For steady state vibration, we set \(u_{r}^{{{\text{II}}}} = R_{1} U_{\eta }^{{{\text{II}}}} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\), \(U_{\eta }^{{{\text{II}}}}\) is the dimensionless radial displacement of the frozen soil in the plastic zone. As a result, the solution to Eq. (9) can be expressed as follows by combing with Eqs. (15), (16), and (20)–(23)

Similarly, the equation of motion for the frozen soil in the elastic zone can be expressed as

where \(\sigma_{r}^{{{\text{III}}}}\) and \(\sigma_{\theta }^{{{\text{III}}}}\) are the radial and circumferential stresses of the frozen soil in elastic zone, respectively; \(u_{r}^{{{\text{III}}}}\) is the radial displacement of the elastic zone in frozen soil and \(\rho_{{\text{f}}}\) is the density of the frozen soil in elastic zone.

For the frozen soil in the elastic zone, the following geometric conditions need to be satisfied

The expression for stresses of the frozen soil in the elastic zone can be rewritten as follows

Then, substituting Eqs. (26)–(29) into Eq. (25) yields

For steady state vibration, we set \(u_{r}^{{{\text{III}}}} = R_{1} U_{\eta }^{{{\text{III}}}} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\), \(U_{\eta }^{{{\text{III}}}}\) is the dimensionless radial displacement of the frozen soil in the elastic zone. Therefore, the equation of motion of the frozen soil in the elastic zone under dynamic loading can be given

where \(h_{{3}}^{2} = - \frac{{\lambda^{2} \left( {2\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)}}{{2\left( {\nu_{{\text{f}}} - 1} \right)}}\rho_{{{\text{fL}}}} \mu_{{{\text{Lf}}}}\).

Based on the boundary conditions, the solution of Eq. (31) can be calculated

where A4 and A5 are the unknown parameters to be determined.

The soil in the unfrozen zone is influenced by soil stress (considering both frozen and unfrozen soil). The frozen soil can be visualized as a cylindrical structure surrounded by unfrozen soil. As the frozen and unfrozen soil operate independently at the interface, there are no corresponding shear stresses. Therefore, the equilibrium of forces at the interface can be expressed as follows46

where 1 and 2 = uniform and deviatoric components of the deformation, respectively. pu and qu are the radial and circumferential stress of the unfrozen soil; pf and qf are the radial and circumferential stress of the frozen soil.

The following dimensionless equations could be given based on the steady-state vibration47

where \(U_{2}^{{\text{d}}}\) and \(V_{2}^{{\text{d}}}\) are the tangential and circumferential displacements of the frozen interface, and \(\nu_{{\text{u}}}\) is the Poisson’s ratio of the unfrozen soil.

Similarly, the dimensionless deformation of frozen and unfrozen soil could be expressed by41

where \(U_{2}^{{\text{f}}}\) and \(V_{2}^{{\text{f}}}\) are the deviatoric components of the frozen soil’s radial and circumferential displacements; \(U_{2}^{{\text{u}}}\) and \(V_{2}^{{\text{u}}}\) are the deviatoric components of the unfrozen soil’s radial and circumferential displacements; \(P_{2}^{{\text{f}}}\) and \(Q_{2}^{{\text{f}}}\) are the deviatoric components of the frozen soil’s radial and circumferential stresses; \(P_{2}^{{\text{u}}}\) and \(Q_{2}^{{\text{u}}}\) are the deviatoric components of the unfrozen soil’s radial and circumferential stresses. \(\overline{I} = I/R_{1}^{3}\) and \(\overline{A} = A/R_{1}^{2}\), where I is the rotational inertia and A is the cross-sectional area of frozen soil.

Governing equation of unfrozen soil and lining

According to the theory of elasticity, the zone of unfrozen soil and lining can be regarded as ideal elastic materials, and the equation of motion can be provided

in which \(\sigma_{r}\) and \(\sigma_{\theta }\) are the radial and circumferential stresses, respectively; \(u_{r}\) is the radial displacement, and \(\rho_{{\text{u}}}\) is the density.

Similarly, the constitutive equations can be written as

where \(\varepsilon_{r}\) and \(\varepsilon_{\theta }\) are the radial and circumferential strains, respectively; E and \(\nu\) are the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio, respectively. The relationship between Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus \(\mu\) can be expressed

Substituting Eq. (45) into Eqs. (43) and (44), the stresses of the zone of unfrozen soil and lining can be obtained

The following geometrical conditions need to be met

Then, substituting Eqs. (46)–(49) into Eq. (42) yields

For steady state vibration, we set \(u_{r}^{{\text{I}}} = R_{1} U_{\eta }^{{\text{I}}} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\) and \(u_{r}^{{{\text{IV}}}} = R_{1} U_{\eta }^{{{\text{IV}}}} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\), where \(U_{\eta }^{{\text{I}}}\) and \(U_{\eta }^{{{\text{IV}}}}\) are the dimensionless radial displacement of the lining and soil in the unfrozen soil, the following dimensionless quantities and constants are introduced to facilitate the calculation

The dimensionless equation of motion of the unfrozen soil and lining can be provided

where \(h_{{4}}^{2} = - \frac{{\lambda^{2} \left( {2\nu_{{\text{u}}} - 1} \right)}}{{2\left( {\nu_{{\text{u}}} - 1} \right)}}\mu_{{{\text{Lu}}}} \rho_{{{\text{uL}}}}\) and \(h_{{1}}^{2} = - \frac{{\lambda^{2} \left( {2\nu_{{\text{L}}} - 1} \right)}}{{2\left( {\nu_{{\text{L}}} - 1} \right)}}\).

According to the properties of the Bessel function \(\left( {\eta \to \infty } \right)\), the solution of Eqs. (52) and (53) can be expressed

where A3 and A1 are the unknown parameter to be determined. \(J_{v} ({*})\) represents the order-ν Bessel function of the first kind, and \(K_{v} ({*})\) represents the order-ν Bessel function of the second kind.

Boundary condition

It is assumed that there is complete contact between the lining and the frozen soil, and there is a relative movement between frozen soil and unfrozen soil. Thus, the continuity conditions and boundary conditions of displacement and stress are satisfied at all the contact surfaces.

At the tunnel invert (r = R1), the external load \(q_{0} {\text{e}}^{{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\) is equal to the radial stress of the lining, i.e.,

At the contact surface between the lining and the frozen soil in the plastic zone (r = R2), the radial stresses and radial displacements of the lining and the plastic zone of frozen soil are the same, i.e.,

At the contact surface between the frozen soil in the plastic zone and the frozen soil in the elastic zone (r = R3), the radial displacement of the frozen soil in the plastic zone is the same as that of the frozen soil in the elastic zone, i.e.,

At the contact surface between the frozen soil in the elastic zone and the unfrozen soil (r = R4), the equilibrium of interface displacements and stresses between frozen and unfrozen soil can be given by Eqs. (33)–(35).

The unknown parameters A1 ~ A5, and B1 in Eqs. (18), (32), (58), and (59) can be obtained from the above continuity conditions and boundary conditions. Then, by substituting the unknown parameters back into the relevant equations, the specific expressions for the steady-state responses of the different zones in Fig. 2 can be obtained.

Verification of the solution and case study

Model validation

To validate the accuracy of the calculations, the model neglects the uniformly distributed load acting on the tunnel invert. Therefore, the tunnel in frozen soil is only affected by the environment, i.e., only the effect of frost heave on the tunnel and its surrounding soil in different frozen states needs to be considered. As shown in Fig. 2, the radial and circumferential stresses after degradation in this study are consistent with the conclusions of reference48. The selected parameters for model validation and parametric analysis are listed in Table 1.

Analysis of factors affecting stresses of medium surrounding the tunnel

In order to investigate the frozen soil in plastic zone on dynamic response of tunnels surrounded by soil with frost heave in cold regions, the changes in radial and circumferential stresses in the tunnel lining and its surrounding soil are shown in Fig. 3. The loads q0 acting on the tunnel invert are 1, 2, and 3, respectively. It can be seen that the greater the external load, the greater the radial stress as well as the circumferential stress in the lining and the plastic zone of frozen soil. As the distance from the loading surface increases, the radial and circumferential stresses gradually decrease. This stress reduction is particularly evident in the plastic zone and at the contact surface between the two media with different properties. When q0 is 1, the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the lining and the plastic zone decrease by 4.83% and 47.51%, respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses in the plastic zone decrease by 28.48% and 62.50%, respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the plastic zone and the elastic zone decrease by 84.10% and 11.80%, respectively. When q0 is 2, the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the lining and the plastic zone decrease by 28.68% and 47.33%, respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses in the plastic zone decrease by 38.76% and 62.69% respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the plastic zone and the elastic zone decrease by 74.32% and 11.50%, respectively. When q0 is 3, the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the lining and the plastic zone decrease by 36.76% and 47.27%, respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses in the plastic zone decrease by 44.00% and 62.75%, respectively; the radial and circumferential stresses at the interface between the plastic zone and the elastic zone decrease by 67.96% and 11.40%, respectively (shown as Table 2). The stresses also decrease at the frozen surface, but it is not significant and tends to stabilize. Additionally, the circumferential and radial stresses become closer in unfrozen soil.

Usually, there are multiple factors influencing ground stress, resulting in variations at different locations. To study the effect of ground stress on the elasto-plastic dynamic response of frozen soil with frost heave around tunnels, the changes in radial and circumferential stresses of the tunnel lining and its surrounding soils are analyzed with different p0 of 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2 (shown as Fig. 4). When the ground stress is low, the radial and circumferential stresses generally decrease with increasing distance from the loading surface. As the ground stress increases, the reduction of radial stress slows down. Furthermore, there is an increase in stress in the frozen soil, including the elastic zone and plastic zone, and the increase becomes more significant with higher ground stress. The radial stress starts to decrease gradually again in the unfrozen soil. As for the circumferential stress, the higher the ground stress, the greater the stress in different zone. However, the stress shows different trends with increasing distance from the loading surface in different zone: the circumferential stress gradually decreases in the plastic zone, decreases significantly at the interface between the plastic zone and the elastic zone, then it increases in the elastic zone and decreases significantly again at the frozen surface. Finally, it decreases slowly in the unfrozen soil.

Analyzing the effect of changes in volumetric frost heaving strain on the elasto-plastic dynamic response of frozen soil with frost heave can approximate the effect of frost heave on frozen soil (Zhang et al., 2023d). As shown in Fig. 5, the volumetric frost heaving strain of frozen soil does not change the trend of radial and circumferential stresses in different zones, but it has a greater effect on circumferential stresses than on radial stresses. With an increase in frost heave, the circumferential stress increases in the lining, plastic zone of frozen soil, elastic zone of frozen soil, and unfrozen soil. The radial stress also increases with an increase in frost heave, but the increase is not as significant as that in circumferential stress.

Analysis of factors affecting displacement in cold-region tunnels

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of changing the thickness of the plastic zone on the radial displacement of soil, while keeping the thickness of the elastic zone constant. When the thickness of the plastic zone reaches 0.7, the effect on the radial displacement of soil in the plastic zone at low frequencies becomes very noticeable. Overall, as the thickness of the plastic zone increases, the radial displacement of frozen soil in the plastic zone increases, while the radial displacement of frozen soil in the elastic zone and unfrozen soil gradually decreases. The effect of changing the thickness of the plastic zone on the radial displacement of frozen soil in the plastic zone is less pronounced compared to the radial displacement of frozen soil in the elastic zone.

Figure 7 demonstrates the effect of changing the thickness of the plastic zone on the stress-displacement of soils with anisotropic frost heave. The radial displacement of the plastic zone slightly decreases and then gradually increases with an increase in the thickness of the plastic zone. The elastic zone and unfrozen soil experience an increase in radial displacement as the thickness of the plastic zone increases. When the thickness of the plastic zone reaches 2, the changes in radial displacement of each medium will gradually stabilize. The radial stress of each medium decreases with an increase in the thickness of the plastic zone. Similarly, when the thickness of the plastic zone reaches 2, the changes in radial stress of different media are not significant.

Figure 8 shows the impact of changes in the elastic zone thickness on the stress-displacement of frozen soil. The influence of elastic zone thickness on the radial displacement and stress of each medium is similar to that of plastic zone thickness. When the elastic zone thickness is small, particularly around 1, the radial displacement of each medium stabilizes. Additionally, the radial displacement of the elastic zone itself stabilizes at a smaller thickness. This indicates that increasing the thickness of the elastic zone can enhance the stability of dynamic impacts on tunnels in cold regions, given a certain thickness of frozen soil in the plastic zone. The effect of elastic zone thickness on the radial stress of different media varies significantly. The radial stress of frozen soil in the plastic zone rapidly increases with increasing elastic zone thickness, reaches a peak, then rapidly decreases and stabilizes. In contrast, the radial stress of frozen soil in the elastic zone increases with elastic zone thickness and tends to stabilize without decreasing. The radial stress of unfrozen soil first increases and then decreases with increasing elastic zone thickness,

Discussion

At present, for the relevant engineering problems produced by operational cold-regions tunnel in China, the main measures can be divided into two categories, i.e., vibration damping technology and freeze-proof technology. Existing methods have been conducted to solve the problems about tunnel vibration, such as the use of vibration dampers, rubber roadbed, steel-spring floating slab track, elastic short damping track, and sound barriers, etc. The above methods are not applicable to reduce the vibration of operational tunnel due to the adaptability or cost, so it is necessary to reduce the tunnel vibration with a stable structure, convenient construction, low cost, and obvious effect. In the vibration sensitive areas of the tunnel, using emulsion treated base layer, graded gravel, rubber sheet to attenuate the vibration energy generated by the tunnel operation48. So far, the frost prevention and control technology of cold-region tunnels in China can be summarized into active measures and passive measures. Active measures are to artificially increase the tunnel structure, surrounding rock, cave air, and groundwater heat; passive measures are to reduce the tunnel structure, surrounding rock, cave air, and groundwater heat21. Tunnels buried in seasonal frozen ground can choose both active measures and passive measures; tunnels buried in permafrost are mainly passive measures, and active measures can be chosen for the drainage system24.

This study theoretically explores the impact of plastic zone in frozen soil on the dynamic response of cold-region tunnel systems. Since the theory of frozen soil is still in the process of development, the dynamic response of the cold-region tunnel systems needs to rely on more advanced theoretical foundations. In addition, although the current analytical method is as close as possible to the practical engineering under the premise of ensuring the accuracy of the calculation, it is still in an ideal state. The transfer of energy and the impact of the movement of the load and other factors will be further considered by experiment, numerical simulation, and in-situ testing, to gradually enrich the theory of the dynamic response of cold-region tunnel systems.

Conclusion

Taking into account the complexity of frozen soil configuration and the limitations of analytical solvability, this study proposes a novel approach to divide the frozen soil into two distinct zones: elastic and plastic. By doing so, we establish an elasto-plastic dynamic model for the incompletely frozen soil-tunnel system, allowing us to derive analytical solutions for the displacements and stresses of both the tunnel lining and the different layers of each medium. The pertinent conclusions and suggestions for engineering are as follows:

-

(1)

Increased external loads result in greater radial and circumferential stresses in the lining and plastic zone. As distance from the loading surface increases, these stresses gradually decrease. Rapid stress reduction occurs at contact surfaces between media with different properties, with different effects on radial and circumferential stresses.

-

(2)

Ground stresses have varying effects on radial and circumferential stresses in different zones surrounding the tunnel. Generally, these stresses increase with higher ground stress, but the trends change as ground stress increases.

-

(3)

Higher volumetric frost heaving strain in frozen soil leads to more pronounced frost heave and increased radial and circumferential stresses in different zones. The change in circumferential stress is greater than that of radial stress. However, as frost heave increases, the radial and circumferential stresses in different zones stabilize.

-

(4)

Varying thicknesses of soil in the plastic and elastic zones affect displacement and stress in different zones. Changes in thickness of frozen soil in plastic zone and elastic zone result in different changes in displacement and stress in different zones of the soil.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

References

Zhao, Y., Zhang, M. & Gao, J. Research progress of constitutive models of frozen soils: A review. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 206, 103720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2022.103720 (2023).

Zhou, W. Y., Guo, D. & Qiu, G. Frozen Soil in China 3–10 (Science Press, 2010).

Fordl, S., Franzius, J. N. & Bartl, T. Design and construction of the tunnel geothermal system in Jenbach. Geomech. Tunn. 5, 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/geot.201000037 (2010).

Zhang, S., Liu, H., Chen, W. & Liu, F. Strength of recompacted loess affected by coupling between acid–base pollution and freeze–thaw cycles. J Cold Reg. Eng. 34(4), 04020024. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CR.1943-5495.000023 (2020).

Xu, X., Li, Q., Lai, Y., Pang, W. & Zhang, R. Effect of moisture content on mechanical and damage behavior of frozen loess under triaxial condition along with different confining pressures. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 157, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2018.10.004 (2019).

Zhang, S. C., Liu, H., Chen, W. & Niu, F. Strength deterioration model of remolded loess contaminated with acid and alkali solution under freeze-thaw cycles. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79(6), 3007–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01721-w (2020).

Sun, Z., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Bai, R. & Li, S. Mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution of frozen soils under the combination of confining pressure and water content. Eng. Geol. 308, 106819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106819 (2022).

Jiang, N., Li, H., Liu, Y., Li, H. & Wen, D. Pore microstructure and mechanical behaviour of frozen soils subjected to variable temperature. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 206, 103740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2022.103740 (2023).

Qiao, J., Zheng, J., Liu, Z., Tang, G. & Liu, Z. The distribution and major engineering problems of special soil and rock along one Belt one Road. J. Catastrophol. 34(S1), 65–71 (2019) (in Chinese).

Zhang, F., Zhu, Z. & Li, B. Soil particle size-dependent constitutive modeling of frozen soil under impact loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 211, 103879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2023.103879 (2023).

Hu, G. et al. Review of algorithms and parameterizations to determine unfrozen water content in frozen soil. Geoderma 368, 114277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114277 (2020).

Li, B., Zhu, Z., Ning, J., Li, T. & Zhou, Z. Viscoelastic-plastic constitutive model with damage of frozen soil under impact loading and freeze-thaw loading. Int. J Mech. Sci. 214, 106890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2021.106890 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. An analytical solution for the frost heaving force considering the freeze-thaw damage and transversely isotropic characteristics of the surrounding rock in cold-region tunnels. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6654778 (2020).

Zhou, Z., Li, G., Shen, M. & Wang, Q. Dynamic responses of frozen subgrade soil exposed to freeze-thaw cycles. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 152, 107010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2021.107010 (2022).

Sun, K., Tang, L., Zhou, A. & Ling, X. An elastoplastic damage constitutive model for frozen soil based on the super/subloading yield surfaces. Comput. Geotech. 128, 103842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103842 (2020).

Wang, P., Liu, E., Zhi, B. & Song, B. A macro-micro viscoelasto-plastic constitutive model for saturated frozen soil. Mech. Mater. 147, 103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2020.103411 (2020).

Gao, G. Y., Chen, Q., Zhang, Q. & Chen, G. Analytical elasto-plastic solution for stress and plastic zone of surrounding rock in cold region tunnels. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 72, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.08.001 (2012).

Niu, F., Zheng, H. & Li, A. The study of frost heave mechanism of high-speed railway foundation by field-monitored data and indoor verification experiment. Acta Geotech. 15(3), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-018-0740-8 (2020).

Zhang, S. C., Chen, W. & Liu, H. Dynamic response of tunnels surrounded by thawing permafrost with anisotropic frost heave in cold regions: Considering the movement of the frozen interface. J Eng. Mech. 149(2), 04022112. https://doi.org/10.1061/JENMDT.EMENG-6885 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Distribution rules and key features for the lining surface temperature of road tunnels in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 172, 102979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2019.102979 (2020).

Lai, J., Qiu, J., Fan, H., Chen, J. & Xie, Y. Freeze-proof method and test verification of a cold region tunnel employing electric heat tracing. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 60, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2016.08.002 (2016).

Tan, X. et al. Study on the influence of airflow on the temperature of the surrounding rock in a cold region tunnel and its application to insulation layer design. Appl. Therm. Eng. 67(1/2), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.03.016 (2014).

Li, S., Niu, F., Lai, Y., Pei, W. & Yu, W. Optimal design of thermal insulation layer of a tunnel in permafrost regions based on coupled heat-water simulation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 110, 1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.09.033 (2016).

Lai, J. X. et al. A state-of-the-art review of sustainable energy based freeze proof technology for cold region tunnels in China. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 82, 3554–3569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.104 (2018).

Huang, C. S., Tseng, Y. & Hung, C. An accurate solution for the responses of circular curved beams subjected to a moving load. Int. J Numer. Meth. Eng. 48(12), 1723–1740. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0207(20000830)48:12%3c1723::AID-NME965%3e3.0.CO;2-J (2000).

Lu, J., Jeng, D. & Lee, T. Dynamic response of a piecewise circular tunnel embedded in a poroelastic medium. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 27(9), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2007.01.010 (2007).

He, C., Zhou, S., Di, H., Guo, P. & Xiao, S. Analytical method for calculation of ground vibration from a tunnel embedded in a multi-layered half-space. Comput. Geotech. 99, 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.03.009 (2018).

Song, W., Zou, D., Liu, T. & Zhou, A. Dynamic response of unsaturated full-space caused by a circular tunnel subjected to a vertical harmonic point load. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 130, 106005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2019.106005 (2020).

Di, H., Zhou, S., Guo, H., He, C. & Zhang, X. Three-dimensional analytical model for vibrations from a tunnel embedded in an unsaturated half-space. Acta Mech. 232(4), 1543–1562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-020-02892-4 (2021).

Yuan, Z., Xu, C., Cai, Y. & Cao, Z. Dynamic response of a tunnel buried in a saturated poroelastic soil layer to a moving point load. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 77, 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2015.05.004 (2015).

Koziol, P. & Neves, M. M. Multilayered infinite medium subject to a moving load: Dynamic response and optimization using coiflet expansion. Shock Vib. 19, 257608. https://doi.org/10.3233/SAV-2012-0707 (2012).

Gao, M., Wang, Y., Gao, G. & Yang, G. An analytical solution for the transient response of a cylindrical lined cavity in a poroelastic medium. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 46, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2012.12.002 (2013).

Zhang, M., Wang, X., Yang, G. & Xie, L. Solution of dynamic Green’s function for unsaturated soil under internal excitation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 64, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2014.05.001 (2014).

Wen, M., Xu, J. & Xiong, H. Thermo-hydro-mechanical dynamic response of a cylindrical lined tunnel in a poroelastic medium with fractional thermoelastic theory. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 130, 105960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2019.105960 (2020).

Forrest, J. A. & Hunt, H. A three-dimensional tunnel model for calculation of train-induced ground vibration. J Sound Vib. 294(4–5), 678–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2005.12.032 (2006).

Di, H., Zhou, S., He, C., Zhang, X. & Luo, Z. Three-dimensional multilayer cylindrical tunnel model for calculating train-induced dynamic stress in saturated soils. Comput. Geotech. 80, 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2016.08.005 (2016).

Yuan, Z., Cai, Y., Sun, H., Shi, L. & Pan, X. The influence of a neighboring tunnel on the critical velocity of a three-dimensional tunnel-soil system. Int. J Solids Struct. 212, 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2020.11.026 (2021).

Fu, T., Zhu, Z., Ma, W. & Zhang, F. Damage model of unsaturated frozen soil while considering the influence of temperature rise under impact loading. Mech. Mater. 163, 104073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2021.104073 (2021).

Wang, L., Wu, Z., Sun, J., Liu, X. & Wang, Z. Characteristics of ground motion at permafrost sites along the Qinghai-Tibet railway. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 29(6), 974–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2008.11.009 (2009).

Zhang, S. & Chen, W. Surface ground vibration of a tunnel embedded in soil layer of cold regions to a moving point load. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 203, 103640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2022.103640 (2022).

Zhang, S. & Chen, W. Dynamic response characteristics of a circular lined tunnel under anisotropy frost heave of overlying soil at the tunnel portal section in cold regions. J. Mt. Sci. 20(5), 1424–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-022-7590-4 (2023).

Chen, W. H. & Zhang, S. C. A spring-like interface between saturated frozen soil and circular tunnel lining under the moving load in cold region without considering frost heave. Res. Cold Arid Reg. 14(6), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcar.2023.02.003 (2023).

Li, S., Li, G., Ou, E. & Wang, C. Train-induced airflow effect on coupled heat and mass transfer in a permafrost tunnel. Int. Commun. Heat Mass 135, 106117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106117 (2022).

Vermeer, P.A. Non-associated plasticity for soils, concrete and rock. In: Physics of Dry Granular Media (eds. Herrmann, H. J., Hovi, J. P., Luding, S.) NATO ASI Series, vol 350. (Springer, Dordrecht, 1998)

Feng, Q., Jiang, B., Zhang, Q. & Wang, L. Analytical elasto-plastic solution for stress and deformation of surrounding rock in cold region tunnels. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 108, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2014.08.001 (2014).

Moore, I. D. Analysis of rib supports for circular tunnels in elastic ground. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 27(3), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01020308 (1994).

Ouakka, S., Verlinden, O. & Kouroussis, G. Railway ground vibration and mitigation measures: Benchmarking of best practices. Rail. Eng. Sci. 30, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-021-00264-9 (2022).

Jiang, W., Jiang, H., Ma, Q., Li, Y. & Li, Z. Unified elasto-plastic solution for cold regions tunnel considering damage and non-uniform frost heave. J. South China Univ. Tech. Nat. Sci. Ed. 50(01), 69–79 (2022) (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the China Academy of Safety Science and Technology (Grant No. 2024JBKY12), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 2021YJS115), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51978039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuocheng Zhang: writing—original draft, methodology, validation, and data curation. Wenhua Chen: review, methodology, supervision, and funding acquisition. Jie Li: editing. Hua Liu: supervision and investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Chen, W., Li, J. et al. A preliminary study on dynamic response of cold-region tunnel systems considering the frozen soil in plastic zone. Sci Rep 15, 5893 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89674-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89674-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Analytical Stress Model for Cold-Region Weakly Cemented Soft Rock Tunnels: Considering Non-uniform Stress and Temperature Fields

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025)