Abstract

An independent pump-controlled hydraulic system based on a variable speed variable displacement power source (VSVDPS) can eliminate throttle losses of the electric loader boom and recover gravitational potential energy. However, challenges arise in efficiently and rapidly solving for the optimal speed and displacement due to severe load fluctuations, model inaccuracies, and the coupling of the two variables. This paper proposes an energy-efficient optimization method based on the model search combined method (MSCM), which leverages the advantages of the model-based method for fast solution finding and the search-based method for high precision. Initially, the model-based method is used to determine the suboptimal speed. Subsequently, based on this speed, the initial speed search interval containing the optimal speed is calculated, enabling the VSVDPS to quickly operate near optimal efficiency during the early stages of the search. Finally, the search-based method is employed to swiftly determine the optimal speed and displacement. The experimental results demonstrate that the MSCM achieves significant energy efficiency improvements with short convergence times. In the hydraulic system of the loader boom, the VSVDPS employing the MSCM reduces energy consumption by 9.38 and 11.27% compared with a variable speed fixed displacement power source and a fixed speed variable displacement power source.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loaders, being commonly used earthmoving construction machinery, are widely employed in sectors such as construction, mining, and ports1,2. Traditional fuel-powered loaders have low efficiency, poor emissions, and serious environmental pollution. In pursuit of green and sustainable development, zero-emission, pollution-free electric loaders have increasingly been utilized3,4. Electric loaders typically utilize centralized power sources with motor speed variations5, hydraulic pump displacement variations6, or dual-variable control7,8. Combined with hydraulic control technology using multi-way valves for flow rate distribution, this enhances the capability to match hydraulic power sources with load power. However, it remains challenging to fundamentally address the energy consumption issues caused by multi-actuator coupling in the flow rate distribution process of centralized power sources9. The frequent lifting and falling of the boom results in significant throttling losses and gravitational potential energy waste, leading to high heat generation, low energy efficiency, and poor battery life in electric loaders10.

To reduce power losses in hydraulic systems, researchers have proposed hydraulic energy-saving technologies such as positive–negative flow rate control11,12, automatic idle control13, and load-sensitive systems14. In addition, energy recovery systems have been designed based on flywheels15, hydraulic accumulators16, and supercapacitors17. Flywheel energy storage systems are widely used in automotive brake energy recovery due to their relatively small size18,19, but their application in the field of construction machinery is relatively rare20. Accumulator-based energy storage systems can quickly absorb and release energy in a short period, making them suitable for applications with rapid load variations. Depending on their structural design, accumulator-based energy recovery systems can be classified into five types: torque coupling16, flow coupling21, balance structures22, hydraulic transformers23, and closed-loop pump control24. Electrical energy recovery systems store the recovered energy in the form of electrical energy in batteries25 or supercapacitors26, making it easier to reuse the recovered energy. Although these methods have reduced energy losses to some extent, throttling losses persist in the system.

To eliminate the energy losses caused by the mismatch between the power source output flow rate and actuator demand flow rate, an independent pump control hydraulic system (IPCHS) is often employed instead of traditional valve-controlled hydraulic systems. In an IPCHS, the inlet and outlet ports of the hydraulic pump are directly connected to both chambers of the hydraulic cylinder and supply the flow rate on demand without throttling or overflow losses27. With advancements in motor and hydraulic pump technology, a motor can operate in both electric motor and generator modes, while a hydraulic pump can operate as both a pump and a hydraulic motor. This versatility allows an IPCHS to freely switch between load driving and energy recovery modes, providing a solution for the efficient lifting and energy recovery of the electric loader boom28,29.

Depending on the method of flow rate regulation, the electro-hydraulic power sources of an IPCHS can be divided into the variable speed fixed displacement power source (VSFDPS), the fixed speed variable displacement power source (FSVDPS), and the variable speed variable displacement power source (VSVDPS). The VSFDPS and the FSVDPS can only adjust one variable. Under certain load working conditions, the power source operates in only one mode, making it difficult for the motor and hydraulic pump to operate efficiently30. However, the VSVDPS can adjust both speed and displacement simultaneously. By appropriately matching the speed and displacement with the premise of achieving flow rate matching, the energy efficiency of the power source can be maximized, offering significant energy savings potential31. However, the VSVDPS faces challenges such as the nonlinear coupling of speed and displacement multiplication and time-varying electrical and hydraulic parameters, which pose difficulties in accurately and rapidly determining the optimal speed and displacement for maximum efficiency.

To determine the optimal speed and displacement for the VSVDPS, Johannes et al.32,33 optimized energy efficiency in dynamic and static processes based on a loss model. However, the loss model overlooked some energy losses such as mechanical losses in the motor, and many parameters in the model were easily influenced by factors such as temperature and load, thereby weakening the effectiveness of energy efficiency optimization. Considering the limitations of the loss model approach, Huang et al.34 proposed a look-up-table method based on experimental data, but this method required a large amount of data and was time-consuming in experiments. In recent years, with the development of artificial intelligence technology, machine learning has been increasingly applied in the engineering field. Leonardo et al.35 introduced a nonlinear model predictive control algorithm, while Rui et al.36,37,38 proposed strategies such as neural networks, extreme gradient boosting integrated with genetic algorithms, and multidimensional controllable variable powertrain systems. Although these methods significantly improved system energy efficiency, they were characterized by complex algorithms and long computation times.

Therefore, to achieve the precise and rapid determination of the optimal speed and displacement of the VSVDPS and thereby ensure the hydraulic system efficiency of the electric loader boom reaching its peak under load driving and energy recovery working conditions, this paper proposes an energy efficiency optimization method based on the model search combined method (MSCM). MSCM is an energy efficiency optimization method that combines the model-based method (MBM) and the search-based method (SBM). Each of these methods has its advantages and drawbacks: MBM offers fast solution times but yields suboptimal optimization results, while SBM provides high solution accuracy but requires longer search times. MSCM integrates the strengths of both MBM and SBM. On the one hand, it avoids shifts in the optimal speed point caused by parameter changes during system operation. On the other hand, it enables the power source to quickly operate near the optimal efficiency early in the search process, thereby reducing energy losses during optimization and shortening the time required for efficiency improvement. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Working principle” introduces the working principles of the hydraulic system for the electric loader boom equipped with the VSVDPS. Section “Energy efficiency model” establishes the energy efficiency model of the VSVDPS and analyzes its efficiency characteristics. Section “Optimization method” describes the design of the MSCM energy efficiency optimization method. Section “Results and discussion” presents the experimental results. Finally, conclusions are drawn in section “Conclusions”.

Working principle

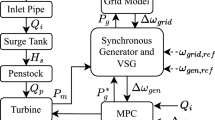

An electric loader boom hydraulic system with the VSVDPS is illustrated in Fig. 1. Depending on the operating state of the power source, it can be categorized into two modes: the electric motor-pump (EMP) mode, and the generator-hydraulic motor (GHM) mode. A permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) coaxially drives a variable displacement piston pump/motor (VDPPM). The inlet and outlet ports of the VDPPM are connected to the two chambers of the boom cylinder. By adjusting the output or input flow rates of the VSVDPS by matching speed and displacement, control of the boom cylinder’s movement speed is achieved. A relief valve ensures that the system operates within a safe pressure range. Solenoid valves 1 and 2 function to maintain pressure during power failure. Pressure and flow sensors return feedback on the state of the hydraulic system. The controller calculates the optimal speed and displacement according to the signal of the joystick and the state of the system, maximizing the efficiency of the VSVDPS operation.

The electric loader boom operates in two modes. When the boom lifts, the VSVDPS operates in the EMP mode. Due to the asymmetry in the flow rate of the boom cylinder, some of the oil drawn by the VDPPM comes from the rod side chamber, while the rest is suctioned through check valve 1 from the hydraulic oil tank. When the boom falls, the VSVDPS operates in the GHM mode. The gravitational potential energy of the boom is converted into hydraulic energy to drive the rotation of the VDPPM, thereby driving the PMSM to generate electricity and store it in the vehicle’s battery. The oil discharged by the VDPPM primarily flows into the rod side chamber, with the excess returning to the hydraulic oil tank through check valve 2, which has back pressure. Check valve 3 prevents the hydraulic motor from vacuuming.

Energy efficiency model

Using the example of the PMSM and the VDPPM operating in the EMP mode, an energy efficiency model for the VSVDPS is established and its efficiency characteristics are analyzed. The analysis process for the GHM mode follows the same procedure as the EMP mode, and is not reiterated in this paper.

Permanent magnet synchronous motor

The efficiency of the PMSM can be expressed as the ratio of the output power to the input power:

where ηm is the efficiency of the PMSM, Pm_out is the output power of the PMSM (W), Pm_loss is the loss power of the PMSM (W), ωm is the mechanical angular velocity (rad/s), Te is the electromagnetic torque (N∙m).

The losses of the PMSM mainly include iron losses, copper losses, and mechanical losses, and their total power loss can be expressed as:

where Pfe is the iron loss (W), Pcu is the copper loss (W), Pme is the mechanical loss (W), pn is the number of poles, ψf is the permanent magnet flux (Wb), Rfe is the iron loss resistance (Ω), Lq is the q-axis inductance (H), Rs is the stator phase resistance (Ω), Cb is the bearing load factor, Dm is the bearing diameter (m), kr is the rotor surface roughness, Cf is the air friction coefficient, ρa is the air density (kg/m3), r is the rotor radius (m), l is the rotor axial length (m).

When the PMSM is in a steady state, neglecting the mechanical losses caused by the connection between the PMSM and the VDPPM shaft, the electromagnetic torque of the PMSM can be expressed as:

where pp is the load pressure of the VDPPM (Pa), Qp is the output flow rate of the VDPPM (m3/s), ηp is the efficiency of the VDPPM.

The relationship between the mechanical angular velocity and the speed of the PMSM is:

where n is the speed of the PMSM (r/min).

Substituting Eqs. (3) and (4) into Eq. (1), when the working conditions are constant, the efficiency of the PMSM can be further expressed as:

where \(A_{1} = \frac{{k_{{\text{r}}} C_{{\text{f}}} \pi \rho_{{\text{a}}} \pi^{3} r^{4} l}}{{27000p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}\), \(A_{2} = \frac{{p_{{\text{n}}}^{2} \psi_{{\text{f}}}^{2} \pi^{2} }}{{600R_{{{\text{fe}}}} p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}\), \(A_{3} = \frac{{\pi C_{{\text{b}}} D_{{\text{m}}}^{3} }}{{30p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}\), \(A_{4} = \frac{{2L_{{\text{q}}}^{2} p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}{{3R_{{{\text{fe}}}} \psi_{{\text{f}}}^{2} }}\), and \(A_{5} = \frac{{600R_{{\text{s}}} p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}{{p_{{\text{n}}}^{2} \psi_{{\text{f}}}^{2} \pi^{2} }}\).

Variable displacement piston pump/motor

The efficiency of the VDPPM can be expressed as the product of the volumetric efficiency and the mechanical efficiency:

where ηpv and ηpm can be represented as39:

where β is described as:

where ηpv is the volumetric efficiency of the VDPPM, ηpm is the mechanical efficiency of the VDPPM, β is the displacement ratio of the VDPPM, Dp is the working displacement of the VDPPM (m3/rad), D0 is the maximum displacement of the VDPPM (m3/rad), μ is the hydraulic fluid viscosity (Pa∙s), Cs is the laminar leakage coefficient, Cv is the laminar resistance coefficient, Cm is the mechanical resistance coefficient, Ts is the torque loss constant (N∙m).

The output flow rate of the VDPPM can be expressed as:

Combining Eq. (7) with Eq. (10), the relationship between the displacement and the speed can be obtained as:

Substituting Eqs. (7), (8), and (11) into Eq. (6), when the working conditions are constant, the efficiency of the VDPPM can be further expressed as:

where \(B_{1} = \frac{{C_{{\text{v}}} D_{0} \pi \mu }}{{1800p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}\), \(B_{2} = \frac{{\pi C_{{\text{m}}} D_{0} p_{{\text{p}}} + \pi T_{{\text{s}}} }}{{30p_{{\text{p}}} Q_{{\text{p}}} }}\), and \(B_{3} = \frac{{2\pi C_{{\text{s}}} D_{0} p_{{\text{p}}} }}{{\mu Q_{{\text{p}}} }} + 1\).

Variable speed variable displacement power source

Combining Eq. (5) with Eq. (12), the overall efficiency of the VSVDPS can be expressed as a polynomial function of speed:

where:

Based on Eq. (13), the efficiency variation of the VSVDPS is plotted with the speed and pressure for different flow rates, as shown in Fig. 2. Higher output flow rates result in higher efficiency of the VSVDPS. As the load pressure increases, the efficiency initially rises and then declines. At lower load pressures, higher speeds result in lower efficiency. When the load pressure exceeds approximately 10 MPa, the efficiency first increases and then decreases with the increasing speed, with the peak efficiency speed point increasing with the flow rate. Overall, there is an optimal speed for any pressure and flow rate working conditions for which the efficiency of the VSVDPS is maximized. Therefore, finding the optimal matching of speed and displacement under the premise of meeting the working performance requirements of the boom is crucial to reducing energy consumption in the hydraulic system of the boom.

Optimization method

Overview of optimization method

The efficient matching of the VSVDPS speed and displacement requires achieving an optimal performance while controlling the optimization time. Therefore, this paper proposes an energy efficiency optimization method based on the MSCM. This method effectively combines the MBM and the SBM, leveraging the MBM’s advantage of fast solution speed and the SBM’s capability of achieving superior optimization results.

The MBM utilizes an energy efficiency model of the VSVDPS to derive the optimal speed directly based on working conditions. The MBM offers advantages such as low online computational requirements and rapid dynamic response. However, variations in the parameters within the energy efficiency model due to factors such as temperature and load can cause deviations between the computed speed and the actual optimal value, thereby weakening the effectiveness of MBM-based energy efficiency optimization.

The SBM is utilized to adjust the operating speed dynamically by monitoring changes in the ratio of input to output power of the VSVDPS online until optimal efficiency is achieved. Unlike the MBM, the SBM does not rely on the energy efficiency model of the VSVDPS, enabling a more accurate determination of the highest efficiency. However, the SBM’s optimization time depends on the initial interval of the speed search. A wider initial interval results in longer search times and more iterations.

MBM and SBM each have their advantages and disadvantages. MBM offers good dynamic performance but results in suboptimal optimization, while SBM provides high solution accuracy but requires longer optimization time. To address this, this paper proposes an MSCM energy efficiency optimization method that combines the strengths of MBM and SBM. The overall design concept for MSCM energy efficiency optimization is as follows: initially, based on the system’s working conditions, the MBM computes a suboptimal speed. Subsequently, an initial speed search interval containing the optimal speed is calculated based on the suboptimal speed. This approach allows the VSVDPS to quickly operate near optimal efficiency during the early stages of optimization. Finally, the SBM is employed to swiftly converge to the optimal speed, ensuring that the VSVDPS achieves maximum efficiency. MSCM integrates the benefits of both methods: on the one hand, it prevents shifts in the optimal speed point caused by parameter variations during system operation; on the other hand, it enables the power source to quickly operate near the optimal efficiency early in the optimization process, reducing energy losses and shortening the time required for efficiency optimization.

Model-based method

MBM energy efficiency optimization involves offline computation of the optimal speeds for different operating points at regular intervals, generating an efficient speed spectrum. During operation, a look-up-table method is used to determine the optimal speed and corresponding displacement for the current working conditions. Given the high-order complexity of the energy efficiency model, this study employs Newton’s method to numerically solve for the optimal speed offline.

Following the basic principles of Newton’s method, Eq. (13) is Taylor expanded around n0, neglecting terms of order two and higher:

Differentiating both sides of Eq. (15) and setting the derivative to zero yields:

Transforming Eq. (16) gives:

Equation (17) provides the next speed point, and this method is iteratively repeated until the convergence conditions are met to obtain the optimal speed.

Newton’s method is utilized to solve for the efficient speed spectrum of the VSVDPS in the EMP and the GHM working modes, as shown in Fig. 3. Based on the efficient speed spectrum, the optimal speed of the VSVDPS can be rapidly determined using the look-up-table method.

Search-based method

SBM energy efficiency optimization involves using the golden section method to search for the most efficient speed based on the variation in the input-to-output power ratio of the VSVDPS monitored online. The golden section method is a technique for finding the minimum value of a one-dimensional function over a closed interval. It determines the search step length according to the golden ratio, progressively narrowing the search interval through iteration, thereby quickly approaching the function’s extreme point. This method is simple, fast, and stable. It does not require the target function to be continuous but must have a unique valley property.

For a unique valley function f(x), if there is a minimum in the interval [a, b], as shown in Fig. 4, two points x1 and x2 can be arbitrarily selected within the interval, with x1 < x2. If f(x1) < f(x2), the minimum value is in the interval [a, x2]; if f(x1) > f(x2), the minimum value is in the interval [x1, b]. By comparing and keeping the interval that contains the minimum value, it is used as the new search interval. The iteration process is repeated until the stopping condition is met, at which point the midpoint of the final search interval is taken as the minimum value of the function.

The key to finding the extreme value of a unique valley function lies in determining the positions of x1 and x2 in such a way that the number of iterations is minimized and the search time is shortened. The core of the golden section method is the identification of the optimal insertion point relationship. The schematic of the golden section search algorithm is shown in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5, the length of the search interval [a, b] is set to 1, with the partition point x1 located at a distance of α from a, and the partition point x2 is at a distance of β from a and at a distance of α from b. According to the principles of the golden section method, it is known that α and β satisfy the relationships α : β = β : 1 and α + β = 1, leading to the values α = 0.382 and β = 0.618.

The steps of the golden section search method are as follows:

-

(1)

Determine the initial search interval [a, b] for the function f(x).

-

(2)

Set x2 = b − α(b − a) and compute f2 = f(x2).

-

(3)

Set x1 = a + α(b − a) and compute f1 = f(x1).

-

(4)

If |b − a| < ε, output the minimum value point xmin = (a + b)/2 and end. Otherwise, proceed to step (5).

-

(5)

If f1 ≤ f2, set b = x2, x2 = x1, f2 = f1, and go to step (3); otherwise, set a = x1, x1 = x2, f1 = f2, and go to step (2), skipping step (3).

As shown in Fig. 2, the efficiency curve of the VSVDPS is a unimodal function with respect to speed, which does not meet the requirements of the golden section method. Therefore, this study adopts the reciprocal of efficiency as the optimization target, which is expressed as:

where γ is the reciprocal of the VSVDPS efficiency, Pin is the input power of the VSVDPS (W), Pout is the output power of the VSVDPS (W).

When the VSVDPS operates in the EMP mode, the input power is the electrical power and the output power is the hydraulic power. Conversely, when the VSVDPS operates in the GHM mode, the roles are reversed. The electrical power and the hydraulic power can be represented as:

where Pelec is the electrical power (W), Phyd is the hydraulic power (W), Urms is the effective phase voltage (V), Irms is the effective phase current (A).

Considering the maximum displacement limit of the VDPPM, when the flow rate demand is fixed, there exists a minimum speed constraint during the operation of the VSVDPS. The minimum speed in the EMP mode can be expressed as:

where nmin is the minimum limiting speed (r/min).

Combining Eq. (7) with Eq. (10), the volumetric efficiency of the VDPPM can be further represented as:

Substituting Eq. (22) into Eq. (21), the minimum speed can be further expressed as:

From Eq. (23), it is evident that the minimum speed of the VSVDPS is a function of the load pressure and output flow rate. Therefore, the minimum operational speed at any given moment can be determined by monitoring the working conditions of the hydraulic system.

The control process for SBM energy efficiency optimization is illustrated in Fig. 6. Initially, the search interval [a, b] is determined, where the rated speed nrated of the PMSM serves as the upper limit and the minimum speed nmin as the lower limit. Subsequently, the speeds x1 and x2 are calculated as two partition points, and the input and output powers of the VSVDPS are monitored online at these speeds. The ratio of the input power to the output power is then computed for both speeds to determine the new search interval through comparison. Finally, a speed threshold εn = 10 r/min is set, and the search concludes when |b − a| < εn, yielding the optimal speed nopt = (a + b) / 2 at which the efficiency of the VSVDPS achieves optimal performance under the current working conditions.

Model search combined method

The schematic diagram for MSCM energy efficiency optimization is depicted in Fig. 7. In both working conditions 1 and 2, all combinations of speed and displacement meet the flow rate requirements of the system. Point A is designated as the operational point of the VSVDPS under working condition 1, point B represents the suboptimal point calculated by the MBM under working condition 2, and point C signifies the optimal point computed by the SBM under the same working conditions. When transitioning from working condition 1 to working condition 2, the MSCM initially directs the VSVDPS to operate from point A to point B, swiftly bringing the VSVDPS close to the optimal efficiency point. Subsequently, using point B as a foundation, the MSCM is utilized to construct a search interval encompassing point C and rapidly guide the VSVDPS to point C, thus achieving rapid and efficient control of the VSVDPS.

The control process of MSCM energy efficiency optimization is shown in Fig. 8, with the steps as follows.

-

(1)

Based on the current working conditions of the system, the operational mode of the VSVDPS is determined, the minimum speed limit nmin is calculated and the suboptimal speed nsub is determined using MBM.

-

(2)

nb = nsub is set, with the current speed set to nb, and γb = Pin/Pout is computed.

-

(3)

na = nb − 0.05nrated is set. If na < nmin, then na = nmin, the current speed is set to na, and γa = Pin/Pout is computed.

-

(4)

nc = nb + 0.05nrated is set. If nc > nrated, then nc = nrated, the current speed is set to nc, and γc = Pin/Pout is computed.

-

(5)

kab = (γa − γb)/(na − nb), kbc = (γb − γc)/(nb − nc) is calculated.

-

(6)

The following are determined.

-

1.

If kabkbc = 0: If kab = 0, the extremum point is within [na, nb], a = na and b = nb are set, and step (7) is enacted. If kbc = 0, the extremum point is within [nb, nc], a = nb and b = nc are set, and step (7) is enacted.

-

2.

If kabkbc > 0: If kab < 0, the extremum point is to the right of nb, γa = γb, γb = γc, na = nb, and nb = nc are set, and step (4) is enacted. If kab > 0, the extremum point is to the left of nb, γc = γb, γb = γa, nc = nb, and nb = na are set, step (3) is enacted, and step (4) is skipped.

If k ab k bc < 0, the extremum point is within [n a, n c], a = n a and b = n c are set and step (7) is enacted.

(7) [a, b] is used as the initial search interval, and the SBM is initiated for optimization.

The principle of MSCM energy efficiency optimization is illustrated in Fig. 9. First, based on the speed command vc and the effective area Ac of the hydraulic cylinder, the required flow rate Qpt is calculated. Combined with the load pressure pp collected by the pressure sensor, the suboptimal speed is obtained through the MBM. Second, the input power is calculated from the three-phase voltage and current monitored by the servo driver. The output power is determined by the pressure and output flow rate monitored by the hydraulic sensor. The initial search interval is determined based on the suboptimal speed and the variation of power ratios. Finally, using the power ratio as the optimization target, the SBM iteratively optimizes until the optimal speed is found. The corresponding displacement is calculated using Eq. (11).

Results and discussion

Experimental setup

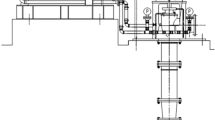

The experimental principles and platform are depicted in Fig. 10, and the experimental parameters are detailed in Table 1. The experimental platform primarily includes the power source hydraulic system (PSHS), loading hydraulic system (LHS), counteracting hydraulic cylinder device (the driving cylinder and the loading cylinder), boom cylinder device, and the electronic control system (ECS). Key components include the controller (MACS-I, MOOG, New York, NY, USA), servo driver (Hi308, HAITIAN, Ningbo, China), PMSM (HP12542-G202F, HAITIAN, Ningbo, China), VDPPM (SCP250, MOOG, New York, NY, USA), and the loader (968EV, XCMG, Xuzhou, China). The PSHS can simulate the VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS. The LHS controls the output oil pressure via proportional valves to simulate various load forces. The PSHS can be connected to either the driving cylinder or the boom cylinder. When connected to the driving cylinder, the PSHS facilitates flexible testing of power sources under different working conditions, and when connected to the boom cylinder, the PSHS tests the energy consumption of the power source under boom conditions.

The specific experimental steps are as follows.

-

(1)

The PSHS is connected to the driving cylinder, the load is simulated using the LHS, and the output flow rate and load pressure are varied. The operational and energy efficiency characteristics of the VSVDPS are tested after applying the MBM, SBM, and MSCM.

-

(2)

The connection form is maintained unchanged, and the energy efficiency characteristics of the VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS are tested. The VSVDPS utilizes the MSCM to control the speed and displacement, the VSFDPS controls the PMSM to operate at the rated speed, and the FSVDPS controls the VDPPM to maintain maximum displacement.

-

(3)

The PSHS is connected to the boom cylinder and the operational and energy consumption characteristics of the VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS are tested for one operational cycle of the boom.

Comparison of optimization methods

Given an initial load pressure of 5 MPa and a demand flow rate of 50 L/min, at 0.5 s the flow rate remains constant. Then the pressure steps up to 10 MPa and is maintained for 1 s. At 1.5 s, the pressure remains constant, and the flow rate steps up to 100 L/min and is maintained for 1 s. The experimental results under varying pressure and flow rate conditions, based on the MBM, SBM, and MSCM for optimizing the VSVDPS energy efficiency, are shown in Fig. 11.

From Fig. 11a, it can be observed that there is some fluctuation in the output flow rate of the VSVDPS during the two working condition changes, but this fluctuation eventually stabilizes to the set value. Figure 11b indicates that compared to the MBM, the convergence time of speed for the MSCM is extended by 0.24 s under both working conditions, with the optimal speeds increasing by 72.95 and 79.83 r/min. Compared with the SBM, the MSCM reduces the speed convergence time by 0.09 s, and the optimal speed aligns closely with the SBM. Figure 11c shows that under both working conditions, the MSCM achieves similar operational efficiency to the SBM, with improvements of 0.298 and 0.163% over the MBM.

To further verify the advantages of the MSCM in the VSVDPS energy efficiency optimization process, MSCM is compared with the particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithm (GA). The experimental results of the VSVDPS energy efficiency optimization based on MSCM, PSO, and GA under the aforementioned operating conditions are shown in Fig. 12.

As shown in Fig. 12a, the speed for both PSO and GA changes only after 0.12 s and 0.15 s, respectively, when the operating conditions change. This indicates that both optimization algorithms require a certain search time. In Fig. 12b, it can be observed that as the operating conditions change, MSCM’s efficiency gradually approaches the optimal efficiency. In contrast, the efficiency of PSO and GA remains relatively low until the optimization process concludes. Once the efficiency stabilizes, MSCM outperforms PSO by 0.049% and 0.011%, and surpasses GA by 0.037% and 0.023%, respectively.

The experimental results demonstrate that the MSCM can achieve more accurate optimal efficiency speeds. Moreover, it enables the VSVDPS to quickly operate near optimal efficiency early in the optimization process, which reduces speed fluctuations during optimization, lowers energy losses, and shortens the convergence time.

Comparison of three power sources

The experimental results show the efficiency of the VSVDPS using the MSCM compared to the VSFDPS and FSVDPS for different flow rates and pressures, as depicted in Fig. 13. In various working conditions, the efficiency of the VSVDPS is consistently greater than or equal to the efficiency of the other two power sources. As the load pressure increases, all three power sources exhibit the trend of a rapid increase followed by a gradual decrease in efficiency. Under low-pressure working conditions, the efficiencies of the VSVDPS and VSFDPS are comparable, with a significant difference compared to the FSVDPS. However, as the pressure increases, the efficiency gap between the VSVDPS and VSFDPS gradually widens, while the difference compared to the FSVDPS diminishes, indicating that at low load pressures, low-speed high-displacement configurations achieve higher efficiency. In contrast, at high load pressures, high-speed low-displacement configurations yield superior efficiency. With increasing output flow rates, the efficiency gap between the VSVDPS and the other two power sources gradually narrows, suggesting that the VSVDPS possesses better energy-savings potential under low flow rate working conditions.

Comparison of three power sources in boom

The working conditions of a loader exhibit a certain periodicity, as illustrated by the “V-shaped” operating cycle. The sequence of boom movements is depicted in Fig. 14. In stage I, as the loader approaches the pile, the boom slightly falls to ensure the bucket is inserted beneath the pile. In stage II, during material loading, the boom lifts slightly to facilitate more effective loading. In stage III, as the loader moves towards the dump truck, the boom lifts to a higher position for dumping material into the truck. In stage IV, after completing the unloading and moving back, the boom falls to its initial position.

The loader boom’s load pressure and demand flow rate during one operating cycle are shown in Fig. 15. During stage I (3–5 s) and stage IV (35–39 s), the boom falls and operates in an energy recovery mode. During stage II (9–10.5 s) and stage III (19–24 s), the boom lifts and operates under load-driven working conditions.

Both the VSVDPS and the VSFDPS achieve switching between power source driving and recovery modes by altering the rotation direction of the PMSM, whereas the FSVDPS switches power source modes by changing the direction of the VDPPM displacement mechanism. The experimental results for the operational characteristics and energy efficiency of the MSCM equipped VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS under boom working conditions are depicted in Fig. 16. Within one operating cycle, the average efficiencies of VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS are 0.86, 0.8, and 0.68, respectively. Compared to VSFDPS and FSVDPS, the energy efficiency of VSVDPS is improved by 7.5% and 26.47%, respectively. In the time intervals of 3–5 s, 9–10.5 s, 19–20 s, and 35–39 s, the efficiency of VSFDPS exceeds that of FSVDPS. However, during the interval of 20–24 s, the efficiency of the VSFDPS is lower than that of the FSVDPS. This is because the VSFDPS demonstrates higher efficiency at low pressures, while the FSVDPS performs better at higher pressures. Overall, under boom working conditions, the VSVDPS achieves the highest efficiency, followed by the VSFDPS, with the FSVDPS having the lowest efficiency.

The energy consumption of the boom hydraulic systems for the three power sources within one operating cycle is illustrated in Fig. 17. Specifically, the energy consumption amounts for the VSVDPS, VSFDPS, and FSVDPS are 344.52, 380.16, and 388.28 kJ, respectively. Compared to the VSFDPS and the FSVDPS, the VSVDPS reduces energy consumption by 9.38 and 11.27%. This demonstrates the fact that the VSVDPS with the MSCM effectively improves the efficiency of the boom system under driving and recovery working conditions, thereby reducing the energy consumption of the electric loader.

Conclusions

To achieve precise and rapid determination of the optimal speed and displacement for the VSVDPS and enhance the energy efficiency of the hydraulic system for an electric loader boom, this paper proposes an energy efficiency optimization method for the VSVDPS based on the MSCM. The experimental conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

Compared to the MBM, the MSCM improves optimization accuracy, and compared to the SBM, the MSCM reduces speed fluctuations during optimization and has a shortened convergence time.

-

(2)

Under various pressure and flow rate working conditions, the efficiency of the VSVDPS using the MSCM is greater than or equal to that of the VSFDPS and the FSVDPS. Particularly in low flow rate working conditions, the VSVDPS shows superior energy-savings potential.

-

(3)

In the hydraulic system of the loader boom, the energy consumption of the VSVDPS using the MSCM is reduced by 9.38 and 11.27% compared to the VSFDPS and the FSVDPS, respectively.

However, the MSCM primarily optimizes the energy efficiency of the VSVDPS without considering the response time and stability during speed and displacement variations. Therefore, future work will integrate considerations of the energy efficiency, dynamic performance, and stability of the VSVDPS, proposing a multi-objective coordinated optimal control strategy.

References

Wang, Y. et al. Design and control performance optimization of dual-mode hydraulic steering system for wheel loader. Autom. Constr. 143, 104539 (2022).

Tong, Z. et al. Development of electric construction machinery in China: a review of key technologies and future directions. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 22(4), 245–264 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Prospects for purely electric construction machinery: Mechanical components, control strategies and typical machines. Autom. Constr. 164, 105477 (2024).

Lin, T. et al. Development and key technologies of pure electric construction machinery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 132, 110080 (2020).

Fu, S., Wang, L. & Lin, T. Control of electric drive powertrain based on variable speed control in construction machinery. Autom. Constr. 119, 103281 (2020).

Liu, B., Quan, L. & Ge, L. Research on the performance of hydraulic excavator boom based pressure and flow accordance control with independent metering circuit. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E-J Process Mech. Eng. 231(5), 901–913 (2017).

Lin, T. et al. A double variable control load sensing system for electric hydraulic excavator. Energy. 223, 119999 (2021).

Ge, L., Quan, L., Zhang, X., Dong, Z. & Yang, J. Power matching and energy efficiency improvement of hydraulic excavator driven with speed and displacement variable power source. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 32(6), 152–163 (2019).

Padovani, D., Rundo, M. & Altare, G. The working hydraulics of valve-controlled mobile machines: classification and review. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 142(7), 1–15 (2020).

Ho, T. & Ahn, K. Design and control of a closed-loop hydraulic energy-regenerative system. Autom. Constr. 22, 444–458 (2012).

Wang, S., Li, Z. & Yu, X. Energy saving analysis and realization of the inverted flux control system of hydraulic excavators. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 29(2), 213–216 (2006).

Xie, H., Liu, J., Yang, H., Zhen, Y. & Zhang, J. Research into the characteristics of slewing hydraulic system on truck crane. Adv. Mater. Res. 317–319, 2409–2415 (2011).

Lin, T. et al. Performance analysis of an automatic idle speed control system with a hydraulic accumulator for pure electric construction machinery. Autom. Constr. 84, 184–194 (2017).

Lin, Z., Lin, Z., Wang, F. & Xu, B. A series electric hybrid wheel loader powertrain with independent electric load-sensing system. Energy 286, 129497 (2024).

Bolund, B., Bernhoff, H. & Leijon, M. Flywheel energy and power storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 11(2), 235–258 (2007).

Jung, T., Raduenz, H., Krus, P., De Negri, V. J. & Lee, J. Boom energy recuperation system and control strategy for hydraulic hybrid excavators. Autom. Constr. 135, 104046 (2022).

Lin, T., Huang, W., Ren, H., Fu, S. & Liu, Q. New compound energy regeneration system and control strategy for hybrid hydraulic excavators. Autom. Constr. 68, 11–20 (2016).

Wang, W., Li, Y., Shi, M. & Song, Y. Optimization and control of battery-flywheel compound energy storage system during an electric vehicle braking. Energy 226, 120404 (2021).

Erhan, K. & Özdemir, E. Prototype production and comparative analysis of high-speed flywheel energy storage systems during regenerative braking in hybrid and electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 43, 103237 (2021).

Li, J., Li, S., Ji, Z. & Wang, Y. Design and energy analysis of a flywheel-based boom energy regeneration system for hydraulic excavators. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1202914 (2023).

Ranjan, P., Wrat, G., Bhola, M., Mishra, S. K. & Das, J. A novel approach for the energy recovery and position control of a hybrid hydraulic excavator. ISA Trans. 99, 387–402 (2020).

Ge, L., Dong, Z., Quan, L. & Li, Y. Potential energy regeneration method and its engineering applications in large-scale excavators. Energy Convers. Manag. 195, 1309–1318 (2019).

Ning, C. M., Chao, Z. Q., Li, H. Y. & Han, S. S. Control performance and energy-saving potential analysis of a hydraulic hybrid luffing system for a bergepanzer. IEEE Access 6, 34555–34566 (2018).

Ge, L., Quan, L., Li, Y., Zhang, X. & Yang, J. A novel hydraulic excavator boom driving system with high efficiency and potential energy regeneration capability. Energy Convers. Manag. 166, 308–317 (2018).

Do, T. C., Nguyen, D. G., Dang, T. D. & Ahn, K. K. A boom energy regeneration system of hybrid hydraulic excavator using energy conversion components. Actuators 10, 1 (2021).

Chen, Q., Lin, T., Ren, H. & Fu, S. Novel potential energy regeneration systems for hybrid hydraulic excavators. Math. Comput. Simul. 163, 130–145 (2019).

Pugi, L., Pagliai, M., Nocentini, A., Lutzemberger, G. & Pretto, A. Design of a hydraulic servo-actuation fed by a regenerative braking system. Appl. Energy 187, 96–115 (2017).

Qu, S., Fassbender, D., Vacca, A. & Busquets, E. A high-efficient solution for electro-hydraulic actuators with energy regeneration capability. Energy 216, 119291 (2021).

Do, T., Dang, T., Dinh, T. & Ahn, K. Developments in energy regeneration technologies for hydraulic excavators: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 145, 111076 (2021).

Yang, J., Liu, B., Zhang, T., Hong, J. & Zhang, H. Application of energy conversion and integration technologies based on electro-hydraulic hybrid power systems: a review. Energy Convers. Manag. 272, 116372 (2022).

Willkomm, J., Wahler, M. & Weber, I. Potentials of speed and displacement variable pumps in hydraulic applications. In 10th International Fluid Power Conference, Dresden, Germany 379–392 (2016).

Willkomm, J., Wahler, M. & Weber, J. Quadratic programming to optimize energy efficiency of speed-and displacement-variable pumps. In 8th FPNI Ph.D Symposium on Fluid Power, Lappeenranta, Finland (2014).

Willkomm, J., Wahler, M., & Weber, J. Process-adapted control to maximize dynamics of speed-and displacement-variable pumps. In ASME/BATH 2014 Symposium on Fluid Power and Motion Control, Bath, United Kingdom (2014).

Huang, H., Jin, R., Li, L. & Liu, Z. Improving the energy efficiency of a hydraulic press via variable-speed variable-displacement pump unit. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 140(11), 111006 (2018).

Cecchin, L. et al. Nonlinear model predictive control for efficient control of variable speed variable displacement pumps. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56(3), 331–336 (2023).

Jin, R., Huang, H., Li, L., Zhu, L. & Liu, Z. Energy saving strategy of the variable-speed variable-displacement pump unit based on neural network. Procedia CIRP 80, 84–88 (2019).

Jin, R. et al. Artificial intelligence enabled energy-saving drive unit with speed and displacement variable pumps for electro-hydraulic systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 21(3), 3193–3204 (2024).

Jin, R. et al. Energy-efficient design of the powertrain for mechanical-electro-hydraulic equipment via configuring multidimensional controllable variables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 201, 114511 (2024).

Ge, L., Quan, L., Zhang, X., Zhao, B. & Yang, J. Efficiency improvement and evaluation of electric hydraulic excavator with speed and displacement variable pump. Energy Convers. Manag. 150, 62–71 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52305082), the Major Science and Technology Projects of the 12th Division Science and Technology Bureau of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps in 2022 (NO. SRS2022003), and the Science and Technology Research Program of Higher Education Institutions in Hebei Province (No.CXY2024034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mingkun Yang: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Guishan Yan: Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Chao Ai: Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition. Xianhang Liu: Visualization, Validation, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, M., Yan, G., Ai, C. et al. Energy efficiency optimization of electric hydraulic loader with variable speed variable displacement power source. Sci Rep 15, 5257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89731-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89731-5