Abstract

We aimed to investigate changes in the ocular disease spectrum during the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in late 2022 in the Hubei Province. This retrospective observational study was conducted in two parts. The first part involved collecting COVID-19-related information from residents of Hubei Province through an online questionnaire survey. The second part involved extracting electronic medical records from ophthalmology outpatient departments at two hospitals in Hubei Province during the pandemic and epidemic prevention and control periods, analyzing changes in the spectrum of ocular diseases. In the first part, 31.65% of patients with systemic symptoms of COVID-19 experienced ocular discomfort. The most common ocular symptoms were eye fatigue, ocular pain and dry eye. In the second part, 76.5% of patients who visited the ophthalmic clinic had COVID-19-related systemic symptoms during pandemic period. The proportion of patients with cornea/keratitis, glaucoma/acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) and vitreoretinal disease/retinal vein obstruction (RVO)/acute macular neuroretinalpathy (AMN) increased markedly during pandemic period. Additionally, the number of patients under 18 years and over 60 years decreased significantly compared to the same age groups pre- & post-pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to certain changes in the spectrum of ocular diseases, which warrants the attention of ophthalmologists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, the first case of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was detected in Wuhan, China, which subsequently resulted in a major global pandemic1. SARS-CoV-2 affects various organs in the human body, causing diverse mild-to-severe and potentially fatal symptoms. The eyes are one of the potential targets of this virus2. From 2020, numerous clinical studies and guidelines have reported that the novel coronavirus can lead to eye diseases3,4,5,6,7,8,9.

Since 2019, the virus has constantly mutated, progressing from the Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Gamma variants to the more recent Omicron variant with decreased pathogenicity and virulence, which has resulted in reduced clinical disease severity10,11. Researchers from China are optimistic about the virus prevention and control, as the proportion of severe and critical COVID-19 cases among all confirmed cases in China has dropped significantly from 16.47% in 2020 to 0.18% by December 5, 202212. However, other researchers maintain a more cautious outlook, emphasizing the need for continued vigilance as the outbreak persists13.

On Dec 7, 2022, the Chinese government announced ten measures marking the end of the zero-COVID policy. Most of the stringent preventive measures, including mandatory PCR testing, are no longer required14. However, the easing of restrictions has contributed to the emergence of new outbreaks predominantly in many cities15,16. Ophthalmologists are facing a huge challenge as many patients with symptoms of COVID-19 have appeared in their ophthalmology clinics. We believe that the recurrent and prolonged nature of the pandemic will have an impact on the spectrum of eye diseases, which is also the primary objective of our study.

To gather information on the detailed profiles of COVID-19-related ocular symptoms and diseases during the pandemic in late 2022, as well as differences in them during the pandemic compared with those during the prevention and control period, ocular data need to be collected by observing patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic period. Hence, the present retrospective observational study aimed to investigate changes in the ocular disease spectrum by analyzing outpatient electronic medical records and online questionnaires during the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2022, which would help us better understand the effect of the pandemic on the eyes.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University and the China Ethics Committee for Registering Clinical Trials (NCT06355128) approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patients included. The study was divided into two parts, one was an online questionnaire survey during the pandemic period (Phase A: December 7, 2022, to January 6, 2023) and the other was information analysis of ophthalmic outpatients both the pandemic period (Phase A) and the prevention and control periods (Phase B: November 7, 2022, to December 6, 2022 and Phase C: December 7, 2021, to January 6, 2022) and the demographic, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics of the patients were compared.

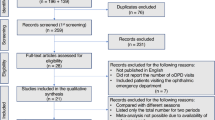

A flow chart for the inclusion of the study participants is presented in Fig. 1.

Online questionnaire survey

We generated a questionnaire and published it on WeChat in Hubei Province. This electronic questionnaire was filled out by participants online using their smartphones. The following information was collected: (1) Informed consent of participants; (2) Duration of systemic and ocular symptoms related to COVID-19 (limited to Phase A); (3) Gender and age of the patients; (4) COVID-19 pathogen test results; (5) COVID-19-related systemic symptoms; (6) COVID-19-related ocular symptoms; (7) Use of topical medications.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) hospitalized patients; (2) patients with severe COVID-19; (3) patients with incomplete information; (4) patients who refused to complete the questionnaire. After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 3,289 participants were finally included in the study (flow chart presented in Fig. 1).

Information analysis of ophthalmic outpatients

The electronic medical records were extracted, including the demographic, epidemiological, and clinical information, from the ophthalmic outpatient department of the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University and its Medical Union and Ophthalmology Specialist Alliance Hospital - Qichun People’s Hospital. The information was compared among Phases A, B and C. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with incomplete electronic medical record information; (2) patients who were registered but did not come to the ophthalmic clinic; (3) patients who could not be contacted by telephone. After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 10,701 patients were finally included in the study (flow chart presented in Fig. 1).

To address this issue during Phase A of this study, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, a comprehensive approach was adopted. Regardless of whether individuals undergoing COVID-19 testing received positive or negative results if they exhibited COVID-19-related systemic symptoms, they were classified as having a COVID-19 infection. This approach acknowledged the limitations and potential inaccuracies of testing methodologies and ensured that individuals with symptomatic presentations were not excluded from analysis solely based on testing results. This inclusive approach provided a more comprehensive understanding of the effect of COVID-19 on our study population during the pandemic phase.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile range [IQR]) and categorical variables are summarized as counts (percentages). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences in age between Phases A and C and Phases A and B. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportions of ocular diseases and sex distribution between Phases A and C, and between Phases A and B. All statistical analyses were performed and graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set to a p-value of 0.05.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of participants who answered the questionnaire during pandemic phase A

In total, 3,289 participants participated in the online questionnaire survey. The demographic data and systemic/ocular symptoms of participants were summarized in Table 1. Among all, 1,090 (33.14%) patients were male, with a median IQR age of 33 (20) years; 962 (29.25%) patients tested positive for COVID-19 nucleic acid or antigen, 1,449 (44.06%) tested negative, and the remaining 878 (26.70%) patients had not undergone COVID-19 nucleic acid or antigen testing.

In total, 739 participants (83.27%) presented COVID-19-related systemic symptoms. The top four symptoms included upper respiratory symptoms (2,435/88.90%), fever (2,089/76%), muscular soreness (1,905/69.55%), and intestinal symptoms (1,050/37.9%). Among patients presenting systemic symptoms of COVID-19, 867 (31.65%) were with concurrent ocular discomforts. The most common ocular symptoms were eye fatigue (419/48.33%), ocular pain (408/47.06%), dry eye (282/32.53%), blurring (264/30.45%), and itching (230/26.53%). In the questionnaire survey, 674 (77.74%) participants who presented ocular symptoms experienced spontaneous relief without any treatment.

COVID-19 infection among ophthalmic outpatients during pandemic phase A

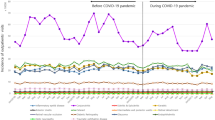

The analyzed data showed that 76.5% (1408/1840) of patients who visited the ophthalmic clinic had COVID-19-related systemic symptoms in pandemic Phase A. The different ocular disease groups of ophthalmologic outpatients were divided into COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 negative, based on whether they presented COVID-19 systemic symptoms or not (Fig. 2). Notably, the proportion of patients presenting COVID-19 systemic symptoms in different disease groups ranged from 68.4 to 100%. Moreover, in seven of the twelve disease groups, more than 75% of patients presented positive COVID-19 symptoms.

The differences in demographic characteristics and ocular disease spectrum in ophthalmic outpatients during different periods

The demographic characteristics and ocular disease spectrum of patients in the ophthalmology outpatient department were compared among Phases A, B, and C (Table 2). Notably, the total number of patients visiting the ophthalmic clinic greatly reduced from 3,292 (Phase B) and 5,441 (Phase C) to 1,968 (Phase A). There were no statistically significant differences in age or sex. The median age of the patients in Phases A, B, and C was 46, 48, and 47 years, respectively; the proportion of male patients was 46.75%, 44.53%, and 45.87%, respectively.

Compared with Phases B and C, a decrease in the proportion of visits was observed in pandemic Phase A for the following ophthalmic specialties: refractive errors, conjunctival diseases, dry eye, and lens diseases. In contrast, an increase in the proportion of visits was observed for the following ophthalmic specialties: trauma, cornea/keratitis, glaucoma/acute angle-closure glaucoma, vitreoretinal disease/RVO/AMN, and strabismus. The ophthalmic specialties with no significant change in the proportion of visits: oculoplastics and orbit, uveitis, and neuro-ophthalmology.

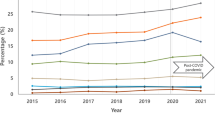

Age distribution of ophthalmic outpatients during different periods

The age distribution of ophthalmologic outpatients was compared across different periods (Fig. 3). Compared with Phases B and C, the number of patients < 18 years and > 60 years decreased considerably in pandemic Phase A. In contrast, in all age groups from 18 to 60 years, the proportion of patients in the pandemic Phase A increased compared with Phases B and C.

Discussion

The questionnaire survey found that fewer people tested positive for COVID-19 antigens than showed COVID-19-related symptoms. Various factors may contribute to this lower positive rate of COVID-19 testing. First, changes in testing policies. The reduction in the number of tests due to the easing of COVID-19 control policies led to a lower detection rate of positive cases. Second, testing methodologies. Some individuals may have opted for the quicker and more convenient antigen test strips for COVID-19 detection, although these tests are less sensitive. Finally, variability in symptom presentation and disease course. Patients with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 may test negative for the virus, particularly during the early stages of infection when viral loads are lower. These variabilities can lead to false-negative results, further exacerbating the discrepancy between symptom prevalence and positive test rates, which is also consistent with existing research findings17,18,19,20.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, many studies and meta-analyses have highlighted the presence of ocular symptoms associated with the virus. These symptoms varied widely in prevalence (range = 0.05–31.6%)21,22,23,24,25,26. Conjunctival congestion has emerged as one of the most frequently reported ocular presentations27,28. Additionally, patients have presented other ocular symptoms such as increased discharge, ocular pain, photophobia, dry eye, tearing, foreign body sensation, irritation/itching/burning sensation, and temporary vision loss23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,−32. In our study, among participants with systemic symptoms of COVID-19, approximately one-third presented ocular discomfort, indicating a high incidence. Interestingly, the incidence of conjunctival congestion was not the highest. This may be because the data for this study was obtained from an online questionnaire survey, the median age of participants was 32 (20), and all individuals presented only mild systemic or ocular symptoms, with none requiring hospital treatment. Notably, 77.73% of participants with ocular discomfort reported spontaneous resolution of their symptoms without any treatment, suggesting that the condition was transient, mild, and reversible.

The data from this study revealed that the number of ophthalmic outpatient visits notably declined within one month after the opening of the epidemic policy (Phase A) and more than 75% of patients exhibited COVID-19-related systemic symptoms, contrasting with zero infected cases in the preceding month (Phase B) and the corresponding period in the previous year (Phase C). Possibly because of the heightened concerns regarding potential COVID-19 exposure in hospitals during this period and considering the fact that many ocular conditions can be managed at a later, non-urgent time.

During the pandemic Phase A, distinct changes were observed in the spectrum of ocular diseases presented in the ophthalmic clinic compared with that of Phases B and C. The proportion of visits for certain conditions reduced, including refractive errors, conjunctival diseases, dry eye, and lens diseases. These changes likely mirrored the overall decrease in ophthalmic outpatient visits. These conditions shared the following common characteristics: slow progression, minimal short-term effects on the vision, and they did not lead to considerable ocular discomfort.

The ophthalmic specialties that showed an increased proportion of visits included trauma, cornea/keratitis, glaucoma/acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG), vitreoretinal disease/RVO/AMN, and strabismus. Notably, keratitis-related visits doubled, whereas AACG-related visits increased eight times. Some cases of keratitis during this period presented typical herpes simplex virus (HSV)-associated dendritic lesions with corneal fluorescent staining. Studies have linked a small number of HSV keratitis cases in patients with COVID-19 since the pandemic outbreak33,34,35,36.

The immune system characteristics in patients with COVID-19, such as immunosuppression and cytokine storm syndrome, may promote the reactivation of latent viral infections such as HSV37,38. The association between HSV and COVID-19 infections suggests that COVID-19 may pose a risk factor for developing or potentially triggering HSV keratitis33,39,40. Studies have shown an increased prevalence of herpes keratitis during the peak of the COVID-19 period, which is consistent with our observations33. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating active human herpesvirus infections in patients with COVID-19 reported no significant difference in the prevalence of active herpesvirus infections between patients with COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 controls, including those with HSV infections and HSV keratitis34. This underscores the need for large cohort studies to systematically investigate the reactivation of herpesviruses in patients with COVID-19.

As China downgraded its prevention and control measures for novel coronavirus pneumonia from Grade A to Grade B in January 2023, AACG cases notably increased, which has been reported at various ophthalmic academic conferences41. A retrospective study examining the morbidity characteristics and risk factors for glaucoma in Huizhou City, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic, revealed that although the overall number of ophthalmic clinic visits decreased, the proportion of AACG cases increased considerably, indicating that testing positive for COVID-19 increased the risk of developing AACG7. This observation is consistent with our findings and suggests the contribution of the COVID-19 pandemic to the increase in AACG occurrence.

The underlying mechanisms for the increase in AACG during the COVID-19 pandemic remain unclear. Various factors, including lifestyle alteration-related physiological and psychological changes during the pandemic, may play a role. For example, reduced levels of physical exercise42,43, decreased sleep quality44,45, lower ambient light exposure because of increased indoor living46, changes in body posture, with more time spent sitting or lying down47,48, and increased screen time49. Additionally, an increase in mental health issues such as anxiety and depression was reported during the COVID-19 pandemic50. These psychological states can lead to autonomic nervous system disorders and stimulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, causing increased adrenaline secretion, pupil dilation, vasomotor dysfunction, ciliary body edema, and other changes51,52. These physiological and psychological changes occur in individuals with certain special ocular anatomy (such as shallow anterior chambers, narrow chamber angles, or short ocular axes), can lead to increased intraocular pressure, impeding aqueous humor outflow, and ultimately triggering an acute episode of AACG.

Other relevant factors have been reported, including studies on COVID-19-induced hyponatremia leading to angle-closure glaucoma in individuals with shallow anterior chamber angles53, cases of bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma following prone ventilation for pneumonia54, and instances of over-the-counter oral cold and flu medications triggering AACG41. Additionally, delayed hospital visits due to epidemic control policies may have contributed to more advanced AACG in patients seeking medical attention. The findings of this study revealed that 5.71% of patients admitted with AACG had onset of symptoms more than a month prior, highlighting the potential impact of delayed medical care during the pandemic.

This study showed a notable increase in RVO and AMN prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the control periods, with Phases A and C showing particularly notable differences.

To date, many studies on retinal vascular occlusions in association with COVID-19, which are limited to case reports have reported an increase in the incidence of retinal vascular occlusions after COVID-19 infection, including retinal artery occlusion (RAO), RVO, and AMN, suggest that retinal vascular damage due to abnormal clotting and thromboembolic events caused by COVID-19 infection may be one of the clinical manifestations of COVID-1955,56,57,58,59. However, in the absence of randomized controls, a complete and sufficient cause-and-effect relationship remains unelucidated. Two cohort studies concerning the incidence of retinal vascular occlusions in the COVID-19 period reported different trends60,61. Bobeck et al. reported an association between COVID-19 infection and RVOs but not with RAOs60. Ahmad et al. reported that the percentages of new cases of RAO and RVO concerning all new diagnoses in retina clinics remained stable for most of the COVID-19 period61. Further large-scale epidemiologic studies are needed to fully elucidate the relationship between retinal thromboembolic events and COVID-19 infection.

This study found no statistically significant differences regarding the age and sex distribution of patients visiting the ophthalmology clinic during Phases A, B, and C. However, the analysis of age distribution revealed a notable decrease in the number of patients aged < 18 and > 60 years during the epidemic period compared with the prevention and control periods. David et al. reported that the incidence and detection rates of COVID-19 were highest in the elderly age group, which may be linked to more extensive testing. Adjusting for testing frequency revealed a reduced infection risk among children and individuals over 70 years old62. This may be due to behavioral factors affecting risk (such as adherence to social distancing, mask-wearing, and other protective measures), variations in detection methods, or differences in awareness levels among different age groups63,64,65,66.

This study has several limitations, including a retrospective, nonconsecutive study design, a relatively short observation period, the presence of unadjusted confounding variables such as past medical history and local or systemic factors, and the lack of serological evidence confirming COVID-19 infection in some patients. It must be acknowledged that establishing a causal relationship between systemic symptoms and ocular manifestations associated with COVID-19 is challenging. However, given the normalization, polymorphism, and persistence of the COVID-19 epidemic, humanity’s battle against the virus is far from over. As such, our study holds significant implications and can contribute to enhancing our understanding of the characteristics and changes in the spectrum of ocular diseases under varying COVID-19 epidemic conditions.

COVID-19 infection has caused varying degrees of impact on multiple organs of the human body, including the eyes, and the characteristics of these effects differing at various stages of the epidemic. Our study compared the changes in the spectrum of ocular diseases across three different phases of the pandemic and found that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to certain shifts in the spectrum of ocular diseases, which warrants the attention of ophthalmologists.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guan, W. J. et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 (2020).

Sen, H. et al. Histopathology and SARS-CoV-2 Cellular localization in eye tissues of COVID-19 autopsies. Am. J. Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2023.02.016 (2023).

Eissa, M., Abdelrazek, N. & Saady, M. Covid-19 and its relation to the human eye: transmission, infection, and ocular manifestations. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 261, 1771–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-022-05954-6 (2023).

Chinese expert consensus on prevention and control of COVID-19 eye disease. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chin. J. Ophthalmol. 58, 176–181 https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112142-20211124-00561 (2022).

Gharebaghi, R. et al. COVID-19: preliminary clinical guidelines for ophthalmology practices. Med. Hypothesis Discovery Innov. Ophthalmol. J. 9, 149–158 (2020).

Park, H. et al. Retinal artery and vein occlusion risks after Coronavirus Disease 2019 or Coronavirus Disease 2019 vaccination. Ophthalmology 131, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.09.019 (2024).

Zhou, H., Liao, R., Zhang, D., Wang, W. & Deng, S. Glaucoma characteristics and influencing factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Huizhou region. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 8889754 https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/8889754 (2023).

Carletti, P. et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated chorioretinal vasculopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. case Rep. 31, 101857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajoc.2023.101857 (2023).

Chung, Y., Yeo, S. & Kim, H. Big data are needed for analysis of the association of retinal vascular occlusion and COVID-19. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 261, 2719–2720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-023-06044-x (2023).

Shuai, H. et al. Attenuated replication and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron. Nature 603, 693–699. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04442-5 (2022).

van Doremalen, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 are attenuated in rhesus macaques as compared to Delta. Sci. Adv. 8, eade1860. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade1860 (2022).

Wu, Z. Wu Zunyou: The proportion of severe and critical cases of COVID-19 in China has dropped from 16.47% in 2020 to 0.18%, https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2022-12-17/doc-imxwxzft0880082.shtml?cre=tianyi&tr=174 (2022).

The Lancet. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2023: far from over. Lancet (London England). 401, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00050-8 (2023).

China’s new 10 measures against COVID-19 are adherence to original intention, logic: Global Times editorial. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202212/1281397.shtml (2022).

Government, H. P. P. s. (2023).

WHO. (2023).

Mallett, S. et al. At what times during infection is SARS-CoV-2 detectable and no longer detectable using RT-PCR-based tests? A systematic review of individual participant data. BMC Med. 18, 346. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01810-8 (2020).

Mercer, T. R. & Salit, M. Testing at scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-021-00360-w (2021).

Testing for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/testing/index.html (2024).

PUBLICATIONS, N. & COVID-19 Test That Relies on Viral Genetic Material Gives False Negative Results if Used Too Early in Those Infected. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/2020/06/covid-19-test-that-relies-on-viral-genetic-material-gives-false-negative-results-if-used-too-early-in-those-infected (2020).

La Nora, D. Are eyes the windows to COVID-19? Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. Ophthalmol. 5, e000563. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000563 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Ocular findings and proportion with conjunctival SARS-COV-2 in COVID-19 patients. Ophthalmology 127, 982–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.028 (2020).

Nasiri, N. et al. Ocular manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 16, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.18502/jovr.v16i1.8256 (2021).

Aggarwal, K. et al. Ocular surface manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 15, e0241661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241661 (2020).

Soltani, S. et al. Pooled prevalence estimate of ocular manifestations in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 47, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijms.2021.89475.2026 (2022).

Wu, P. et al. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138, 575–578. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291 (2020).

Cao, K., Kline, B., Han, Y., Ying, G. S. & Wang, N. L. Current evidence of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) ocular transmission: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 7605453 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7605453 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Ocular manifestations and clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Acta Ophthalmol. 98, e951–e959. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14472 (2020).

Chen, Y. Y., Yen, Y. F., Huang, L. Y. & Chou, P. Manifestations and virus detection in the ocular surface of adult COVID-19 patients: a Meta-analysis. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 9997631 https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9997631 (2021).

Zhong, Y. et al. Ocular manifestations in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 44, 102191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102191 (2021).

Pace, J. et al. Ophthalmic presentations and manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review of global observations. Cureus 15, e40695. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.40695 (2023).

Szkodny, D., Wylęgała, A., Chlasta-Twardzik, E. & Wylęgała, E. The ocular surface symptoms and tear film parameters during and after COVID-19 infection. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11226697 (2022).

Majtanova, N. et al. Herpes Simplex Keratitis in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a series of five cases. Med. (Kaunas Lithuania). 57 https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050412 (2021).

Banko, A., Miljanovic, D. & Cirkovic, A. Systematic review with meta-analysis of active herpesvirus infections in patients with COVID-19: Old players on the new field. Int. J. Infect. Diseases: IJID : Official Publication Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 130, 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.036 (2023).

Das, N., Das, J. & Pal, D. Stromal and endothelial herpes simplex virus keratitis reactivation in the convalescent period of COVID-19 - a case report. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70, 1410–1412. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2838_21 (2022).

Baj, J. et al. How does SARS-CoV-2 affect our eyes-what have we Learnt so far about the ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19? J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11123379 (2022).

Chowdhury, M., Hossain, N., Kashem, M., Shahid, M. & Alam, A. Immune response in COVID-19: a review. J. Infect. Public Health. 13, 1619–1629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.001 (2020).

Xu, R. et al. Co-reactivation of the human herpesvirus alpha subfamily (herpes simplex virus-1 and varicella zoster virus) in a critically ill patient with COVID-19. Br. J. Dermatol. 183, 1145–1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19484 (2020).

Katz, J., Yue, S. & Xue, W. Herpes simplex and herpes zoster viruses in COVID-19 patients. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 191, 1093–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02714-z (2022).

Maldonado, M., Romero-Aibar, J. & Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. COVID-19 pandemic as a risk factor for the reactivation of herpes viruses. Epidemiol. Infect. 149, e145. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268821001333 (2021).

Yin, X., Li, X. & Liang, X. Acute angle closure glaucoma in COVID-19 patients may be precipitated by nonprescription oral cold and flu medication: a literature review. Asian J. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.11.166 (2023).

Chong Seong, N. et al. Effect of physical activity on severity of primary angle closure glaucoma. Therapeutic Adv. Ophthalmol. 11, 2515841419864855. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515841419864855 (2019).

Ammar, A. et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061583 (2020).

Barrea, L. et al. Does Sars-Cov-2 threaten our dreams? Effect of quarantine on sleep quality and body mass index. J. Translational Med. 18, 318. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02465-y (2020).

Yuan, S. et al. Comparison of the indicators of psychological stress in the population of Hubei Province and non-endemic provinces in China during two weeks during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in February 2020. Med. Sci. Monitor: Int. Med. J. Experimental Clin. Res. 26, e923767. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.923767 (2020).

Arimura, S. et al. Determinants of anterior chamber angle narrowing after mydriasis in the patients with cataract. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 253, 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2817-x (2015).

Sawada, A. & Yamamoto, T. Posture-induced intraocular pressure changes in eyes with open-angle glaucoma, primary angle closure with or without glaucoma medications, and control eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 7631–7635. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10454 (2012).

Prata, T., De Moraes, C., Kanadani, F., Ritch, R. & Paranhos, A. Posture-induced intraocular pressure changes: considerations regarding body position in glaucoma patients. Surv. Ophthalmol. 55, 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.12.002 (2010).

Balanzá-Martínez, V., Atienza-Carbonell, B., Kapczinski, F. & De Boni, R. Lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 - time to connect. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 141, 399–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13177 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PloS One. 15, e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 (2020).

Flammer, J. & Prünte, C. [Ocular vasospasm. 1: functional circulatory disorders in the visual system, a working hypothesis]. Klin. Monatsbl. Augenheilkd. 198, 411–412. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1045995 (1991).

Wierzbowska, J., Wierzbowski, R., Stankiewicz, A. & Robaszkiewicz, J. [Autonomic nervous system and primary open angle glaucoma–pathogenetic and clinical correlations]. Klin. Ocz. 111, 75–79 (2009).

Özmen, S., Özkan Aksoy, N., Çakır, B. & Alagöz, G. Acute angle-closure glaucoma concurrent with COVID 19 infection; case report. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 33, NP42–NP45. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721221113201 (2023).

Nerlikar, R., Palsule, A. & Vadke, S. Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma after prone position ventilation for COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Glaucoma. 30, e364–e366. https://doi.org/10.1097/ijg.0000000000001864 (2021).

Yeo, S., Kim, H., Lee, J., Yi, J. & Chung, Y. Retinal vascular occlusions in COVID-19 infection and vaccination: a literature review. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 261, 1793–1808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-022-05953-7 (2023).

Ashkenazy, N. et al. Hemi- and central retinal vein occlusion associated with COVID-19 infection in young patients without known risk factors. Ophthalmol. Retina. 6, 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2022.02.004 (2022).

O’Donovan, C., Vyas, N. & Ghanchi, F. Retinal vein occlusion with COVID-19: a case report and review of literature. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 31, 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2022.2032196 (2023).

Gascon, P. et al. Covid-19-associated retinopathy: a case report. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 28, 1293–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2020.1825751 (2020).

Ucar, F. & Cetinkaya, S. Central retinal artery occlusion in a patient who contracted COVID-19 and review of similar cases. BMJ Case Rep. 14 https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-244181 (2021).

Modjtahedi, B., Do, D., Luong, T. & Shaw, J. Changes in the incidence of retinal vascular occlusions after COVID-19 diagnosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 140, 523–527. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.0632 (2022).

Al-Moujahed, A. et al. Incidence of retinal artery and vein occlusions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Opthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 53, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/23258160-20211209-01 (2022).

David, N. COVID-19 case age distribution: correction for differential testing by age. Ann. Intern. Med. 174 https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-7003 (2021).

Stringhini, S. et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): a population-based study. Lancet (London England). 396, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31304-0 (2020).

Han, M. et al. Clinical characteristics and viral RNA detection in children with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3988 (2021).

Brankston, G. et al. Socio-demographic disparities in knowledge, practices, and ability to comply with COVID-19 public health measures in Canada. Can. J. Public. Health = Revue canadienne de sante Publique. 112, 363–375. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00501-y (2021).

Alsan, M. et al. Comparison of knowledge and information-seeking behavior after general COVID-19 public health messages and messages tailored for Black and Latinx communities: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 484–492. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-6141 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Min Ke, Xiaomin Chen designed the study. Qing Bao,Xiaomin Chen,Yuting Li,Yaoyao Ren,Yanru Shen complete the online questionnaire and collect the results. Zhiwei Zheng,Yan Zheng,Nan Zhang extracted electronic medical records from ophthalmology outpatient departments. Qing Bao, Yanru Shen and Xiaomin Chen analyzed the results. Xiaomin Chen wrote the main manuscript. Qing Bao prepared figures and Tables. Min Ke, Xiaomin Chen revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, Q., Shen, Y., Zheng, Z. et al. Changes in the spectrum of ocular disease during the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2022 in the Hubei Province. Sci Rep 15, 6297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89791-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89791-7