Abstract

The potential risk for CO2 leakage from carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems has raised significant concerns. While numerous studies have explored how crops respond to elevated soil CO2 levels, relatively few have examined the impacts on vegetables. Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are a key vegetable crop, and this study sought to investigate how CO2 leakage affects their yield and quality. We conducted pot experiments comparing tomatoes grown under control conditions (no added CO2) with those exposed to elevated soil CO2 levels (1500 g m−2d−1). Our findings indicate that under CO2 leakage conditions, the overall biomass of tomato plants, average fruit weight, and fruit size decreased by 47.42%, 47.65%, and 20.2%, respectively. Notably, the titratable acid content in the tomatoes increased by 27.5%, resulting in a sourer taste. The tomato fruit grades and sugar acid ratio declined leading to a seriously commercial value loss of tomatoes in response to elevated soil CO2 levels. This study provides a more quantitative understanding of how vegetables like tomatoes respond to CO2 leakage, which is crucial for CCS decision-makers to comprehend the adverse effects of CO2 leaks on agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is an effective technique to achieve significant CO2 emission reductions by sequestering anthropogenic CO2 in deep geological formations1. Although the likelihood of CO2 leakage from a CCS system is low2, some leakage accidents were reported in Salah, Algeria3, and Weyburn-Midale, Canada4. It is, therefore, necessary to consider the potential consequences of such leaks by assessing both the ecosystem impact and the environmental risk5.

Zero Emission Research and Technology project (ZERT) and Artificial Soil Gassing and Response Detection (ASGARD) have focused on plant responses to CO2 leakage using artificially controlled CO2 release from shallow soil6,7. The reaction of physiology and morphology of crop plants has been investigated repeatedly under the influence of CO2 leakage8. A significant biomass decrease in the roots and stems occurs when the roots are exposed to very high concentrations of CO29. The harvested dry matter of teosinte declined by over 70% under 500–2000 g m−2d−1 CO2 leakage treatments than that of the untreated control10. When CO2 leakage exceeded 500 g m−2d−1, alfalfa plants showed decreased height and stunted leaf areas. Under a CO2 leakage rate of 2000 g m−2d−1, the height of maize plants was only 53.4% of plants observed without CO2 leakage11. Furthermore, exposure to elevated soil CO2 reduced spring field bean (Vicia faba L.) pod and seed numbers by 42% and 46%, respectively, and reduced the seed weight per plant by 36%12. Therefore, CO2 leakage from CCS has been shown to hurt plant growth. However, to date, experiments have mainly focused on crop plants, and only a few studies have investigated the impact of CO2 leakage on vegetables.

With a rich composition of bioactive compounds, tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are one of the most nutritious vegetables consumed worldwide13. The global production and plantation areas of tomatoes reached 177 million tons and 5 million hectares in 2016, respectively14. Tomatoes are planted in the greenhouse and open fields, with organic and conventional management15. CO2 is the basis for photosynthesis, affecting tomatoes’ yield. Under facility agriculture, applying an appropriate amount of CO2 in the air as fertilizer is essential for obtaining high outcomes and good-quality tomatoes. The net photosynthetic rate of tomato leaves can be significantly increased by exposure to high concentrations of CO2 during plant growth16. With increased atmospheric CO2 concentration, the number of flowers, fruit layers, and dry matter increased significantly17,18. Upon treatment with a CO2 concentration of 800 ± 25 µmol mol−1, the soluble sugar content in tomatoes was higher than that in the control group, and the glucose and fructose contents increased significantly by 46% and 42%, respectively19. When the indoor CO2 concentration was increased to 1000–1200 µL L−1, the tomato yield and ascorbic acid were enhanced by 26.48% and 33.27%, respectively20. However, all of the above are responses of tomatoes to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations; little is known about tomato yield and quality response to the elevated soil CO2 levels due to CCS leakage.

In this study, tomato plants were tested in a pot experiment to simulate CO2 leakage from a CCS project. The physical traits of tomatoes, including their biomass, height, fruit weight, and fruit maximum perimeter, were examined. Tomato nutritional qualities were also determined, including soluble sugar, titratable acid, and ascorbic acid content. The main aim was to test the hypothesis that the leaked CO2 induces a significant decline in tomato yield and quality. This will provide quantitative results to assess the effects of CO2 leakage on vegetables.

Materials and methods

Controlled CO2 release device and soil type

The experiment was conducted using a CO2 leakage control system. The system consisted of a CO2 release device, a pot, and a CO2 detector. CO2 was injected into the soil at the bottom of the pot. The pots (100 cm high × 50 cm long × 50 cm wide) were divided into two sections by a gas-permeable separator. The upper Sect. (80 cm) comprised the soil chamber for plant growth (50 cm soil thickness), and the lower Sect. (20 cm) was an air chamber that released CO2 gas. The soil used in the test pots was collected from topsoil in surrounding farmland. The regional soil is mainly tidal cinnamon soil (pH 8.38, organic matter 15.48 g kg−1, total N 0.37 g kg−1, total P 0.61 g kg−1, and total K 20.42 g kg−1). Before sowing, 75 g of base fertilizer (10 g urea, 50 g calcium superphosphate, and 15 g potassium sulfate including N 4.69 g, P 6 g, and K 7.5 g) was applied to each pot and watered with 15 L of water.

Planting and management

The experimental site was at the Shunyi Agro-Environmental Integrated Experimental Base (40° 13′N, 116° 14′E) of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The local area has a temperate continental monsoon climate and is in the transition between semi-arid and semi-humid, temperate, and mid-temperate regions. The annual average temperature, precipitation, and sunshine hours are approximately 11–12 °C, 640 mm, and 2000–2800 h, respectively21.

Marwa tomatoes from the Netherlands were used in this experiment. The tomatoes were plastic-plate dot sowed on June 28, 2020, and seedlings were transplanted in a cultivation box on July 19, 2020. One seedling was grown in each pot for three weeks.

CO2 leakage treatment setting

The CO2 injection flux (hereafter, flux) was used to measure CO2 leakage intensity. The flux of natural CO2 seepage is 1000–3000 g m−2d−1, and the upper limit tolerance threshold for maize is 2000 g m−2d[−111. Based on this data, 1500 g m−2d−1 CO2 was selected to inject into the soil chamber of the pots with the tomato plants. The treatments were set up as leakage throughout the growth period (Leakage treatment). In addition, there was also one control, non-leakage treatment (CK treatment). Five replicates were performed for each treatment (Fig. 1). There was a two-meter gap between each treatment to prevent interference between the pots.

(a) Photograph and (b) A schematic of the experiment used to evaluate tomato response to CO2 leakage simulation. CO2 permeates the soil from the bottom through tiny openings with a diameter of roughly 0.5 cm. CK, no CO2 injection; Leakage treatment, 1500 g m−2d−1 CO2 leakage throughout the tomato growth period.

In the fourth week after transplanting, the tomato plants had four or five true leaves spread out, and CO2 began to leak out. The CO2 released to the WL group began on August 14, 2020, and the tomato harvest on November 21, 2020. The leakage flux was calculated as follows11:

Where F is the CO2 leakage flux (g m−2 d−1), v is the CO2 injection rate (mL min−1), ρ is the density of CO2 under atmospheric pressure (approximately 1.977 g L−1), and s is the cross-sectional area of the cultivation box (0.25 m2). Hence, the CO2 injection rate was 132 mL min−1.

Measurement and analysis

The plant height was recorded weekly. Tomato fruits were harvested on November 21, 2020. The number and weight of harvested fruits were recorded, and the maximum perimeter (n = 71 fruit) was measured. After harvest, the roots and stems were pretreated with high-temperature desiccation at 120 °C and dried at 80 °C to a constant weight. The aboveground (except the fruit) and underground biomass were weighed afterward. The response characteristics of tomatoes to CO2 leakage were evaluated by comparing the differences in biomass, production, and nutritional quality between the leakage treatments.

The tomatoes were freeze-dried and sent to a testing center at the Institute of Agricultural Environment and Sustainable Development (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) to determine their soluble sugar, titratable acid, and ascorbic acid contents. Soluble sugar content was determined using colorimetry of anthrone-sulfuric acid following the agricultural chemical analysis methods (SSC-39.2.3). Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content was determined using the 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP) Association of Official Analytical Collaboration (AOAC) method22, and the titratable acid content was determined according to the AOAC method (942.15)23.

Tomato fruit grading and taste assessment

The tomato fruits harvested will be graded according to the Industry Standards “Grades and specifications of tomatoes (NY/T 940–2006)” and “Tomatoes grading (GH/T 1193–2021)” issued by the Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Affair of People’s Republic of China and All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperative.

The sugar acid ratio refers to the ratio of soluble sugars to titratable acids in fruits, and is one of the essential reference indicators for measuring taste. It is generally believed that the appropriate sugar acid ratio for tomatoes is 6.9–10.824.

Here, R is sugar acid ratio, dimensionless; \(\:{S}_{Soluble}\) is soluble sugar, %; \(\:{A}_{Titratable}\) is titratable acid, %.

We determined the magnitude of the effect by comparing the means from the leakage and control groups. All experimental data were analyzed using the independent sample t-test in SPSS 19.0, and significance was indicated at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Tomato biomass and development

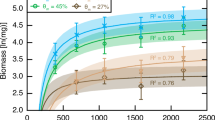

We found that increased soil CO2 levels led to a significant decrease in tomato aboveground biomass. The aboveground biomass values were 147.33 ± 6.54 g and 71.02 ± 10.37 g under CK and leakage treatments, and the biomass of the leakage group decreased by 51.79% compared to the CK treatment (Table 2). However, the groups had no significant difference in the underground biomass (Fig. 2a). The total biomass (including aboveground and underground) of the leakage treatments decreased significantly by 47.42% compared to that of CK. As shown in Fig. 2b, the plant height did not differ considerably between CK and leakage groups, with the average plant height of the tomato plants reaching 95.20 ± 4.35 cm and 94.00 ± 3.27 cm, respectively (Table 2).

Biomass, plant height, fruit weights, and perimeters of the tomatoes for the control and leakage treatments (CO2 leakage during the tomato growth period). (a) Above- and underground biomass of tomato. The indicators shown are aboveground biomass under control treatment (Above_Control), aboveground biomass under leakage treatment (Above_leakage), underground biomass under control treatment (Under_Control), and underground biomass under leakage treatment (Under_ leakage). The vertical line in each box is the median value, and the box graph is drawn using the quartile method. (b) Tomato plant heights. (c) Weight of a single fruit and (d) the largest fruit perimeter per plant (mm). The horizontal line in each box is the median value, and the box graphs were drawn using the quartile method. CK is the control (no CO2 leakage); the leakage group is the experimental group where CO2 leakage occurred throughout the growth period, with a leakage amount of 1500 g m−2d−1. All groups were subjected to the same water and heat conditions.

The CO2 leakage during the whole tomato growth period with a 1500 g m−2d−1 CO2 injection, and the CK group (control) had no CO2 injection. The asterisk represents a significant difference between CK and the treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Tomato grading

The CK and leakage groups harvested 22 fruits; the average fruit weights were 124.40 ± 15.69 g and 71.03 ± 8.46 g, respectively. The maximum perimeter of the tomato fruits reached 194.36 ± 9.76 mm and 166.59 ± 7.82 mm under CK and leakage treatments, respectively (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 2c and d, compared to the CK group, the average weight and size of fruit in the leakage group decreased significantly by 42.90% and 14.28%%, respectively. Total tomato fruit weights were 2825.46 g and 1606.22 g under CK and leakage treatments. The largest fruit perimeter of tomato reached 194.36 ± 9.76 mm and 166.59 ± 7.82 mm under CK and leakage treatments, respectively (Fig. 2d). The weight and size of tomatoes in the CO2 leakage groups showed a significant decreasing trend compared to the CK group.

According to the tomato fruit grading standards (Table 1), the fruit weight of CK meets the middle grade, and that of leakage treatment drops down to a samll grade. Compared to the CK group, the fruit diameters of leakage treatment declined from 61.89 ± 3.11 mm to 53.05 ± 2.49 mm, but both are still classed in small grades (Table 2).

Tomato’s nutritional quality and taste

Figure 3 shows that the average ascorbic acid and soluble sugar contents of the tomatoes are 23.76 ± 3.66 mg/100 g, 3.22 ± 0.18% under CK treatments, and 19.94 ± 2.77 mg/100 g, and 3.54 ± 0.27% under CO2 leakage treatments (Table 3). However, the titratable acid content increased by 29.16% from 0.48 ± 0.02% to 0.62 ± 0.05 under the 1500 g m−2 d−1 treatments, which led to the sugar acid ratio decreased sharply. Under the CK treatments, the sugar acid ration of tomato fruits is 6.71 ± 0.51, which is near the lower limit of best taste (6.9–10.8). When a 1500 g m−2d−1 CO2 leak occurs, the sugar acid ration of tomato falls to 5.64 ± 0.44, a decrease of 15.95%.

Ascorbic acid (mg/100 g), soluble sugar (%), titratable acid (%), and sugar acid ratio of the tomatoes for the control and leakage treatments (CO2 leakage during the tomato growth period). The blue and orange dots represent control and leakage treatments. The dashed line shows the tomatoes’ appropriate sugar acid ratio (6.9–10.8).

Discussion

This study investigated the response of tomato yield and quality caused by elevated soil CO2 concentration from a pot simulation of leaking CCS project at a rate of 1500 g m−2 d−1 (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2a; Table 2, elevated soil CO2 reduced the tomato plant biomass by 47.42%, which is comparable with the results of Zhang et al., who found that maize biomass decreased by 67.9% with a CO2 leakage concentration of 1500 g m−2 d−15. The harvested dry matter of teosinte declined by over 70% under 500–2000 g m−2d−1 CO2 leakage treatments than that of the untreated control10. Therefore, scholars have achieved a relatively consistent understanding of the negative impacts of CCS leakage on plant biomass and yields. The biomass response of tomatoes follows this pattern as well. Furthermore, this study introduced the fruit grading standard into the assessment system. According to Table 2, the grades of tomato fruits decreased from moderate to small in the three-level grading system during the single fruit weight and significantly decreased from 124.40 ± 15.69 g to 71.03 ± 8.46 g. This suggests that the impact of CCS leakage on fruit producing vegetables not only needs to consider a significant decrease in vegetable yield, but also causes a decline in fruit grade, further expanding economic losses.

Fruit flavor is an important economic trait for evaluating fruit quality, and it is also one of the essential sensory indicators that determine consumers’ choices25. As shown in Fig. 3; Table 3, the titratable acid content significantly increased by 29.16% under the 1500 g m−2 d−1 treatment, which led to the sugar acid ratio decreasing sharply. Generally, the appropriate sugar acid ratio for tomatoes is 6.9–10.8 24. Under the CK treatments, the sugar acid ratio of tomato fruits is 6.71 ± 0.51, which is near the lower limit of best taste (6.9). When a 1500 g m−2d−1 CO2 leak occurs, the sugar acid ratio of tomato falls to 5.64 ± 0.44, a decrease of 15.95%. It is not difficult to infer that due to the decrease in tomato sugar acid ratio causing poor taste, CCS leakage will lead to a significant decrease in the commercial value of tomatoes.

The elevated soil CO2 caused by CCS leakage is a rare environmental stress for tomato quality assessment. Compared with other frequently discussed stress, such as salt, drought, and flooding, the taste of tomato under the stress of CCS leakage displayed some consistent characteristics. Li et al. reported that saline water irrigation increased the glucose contents at a mature period by 31.55% compared with freshwater irrigation26. Salt stress could increase carbohydrate accumulation by 18.34% in the tomato fruits, while organic acids were 1.71 times that of control. It will decrease the sugar acid ratio of tomatoes27. It can be seen that the response of tomatoes to salt stress and soil CO2 increase stress is very similar, ultimately leading to a decrease in tomato sugar acid ratio and a deterioration in taste. However, drought stress also severely affects tomato yield and quality28. The mild water deficit could increase the total amount of organic acids and soluble sugar. Water deficit could increase the sugar acid ratio of tomato fruit, with an increase of 8.17%24. That is to say, drought may lead to an improvement in tomato taste, which is different from the impact of increased soil CO2 stress. The observation of plant height, the number of leaves, leaf area, and relative growth rate were significantly reduced under flooding compared to the control29. Feng et al. reported that soil moisture content under waterlogging positively interacts with titratable acid accumulation in tomatoes30. Flooding stress may also cause tomato flavors to become sour. It can be seen that tomatoes have significant differences in their response to different types of environmental stress, and the response results of CCS leakage stress enrich our understanding of tomato characteristics.

As shown in Fig. 2b, the plant heights of tomatoes remained unchanged when exposed to 1500 g m−2 d−1 CO2 leakage. Notably, the plant height of maize, alfalfa, clover, teosinte, and millet decreased under leaked CO2 treatment8,31,32. All these experiments suggest that crop height has a consistently negative response to CO2 leakage. Furthermore, the underground biomass of tomato showed no reaction to CO2 leakage, which also differed from previous results, which showed that the root length and root volume of maize were reduced by 44.73% and 19.16, respectively, under 1000 g m−2 d−1 of CO2 leakage33. This suggests that the tomato morphology is insensitive to elevated soil CO2, and the main effect of CO2 leakage on tomato plants is on their fruit yield and quality. Tomatoes have strong adaptability to environmental stress34. Detailed monitoring and assessments of tomato plants and other plant responses are necessary to evaluate such differences further.

Compared with previous studies1, our results further revealed the response of tomato fruit degradation and taste worse, which will further amplify the economic losses caused by CCS leakage on plants. However, some component gaps that affect the flavor of the tomato (e.g., volatile compounds) in our experiments should be considered in future studies. The yield and quality response characteristics for CCS leakage, while the underlying mechanistic explanation, are still far from being answered. The impact of elevated soil CO2 on the biosynthesis pathways of tomato flavor-contributing substances and the changes in the main enzyme activities involved are still unknown.

Conclusions

This pot experiment demonstrated tomato yield loss and quality degradation caused by elevated soil CO2 concentration from a pot simulation of failure CCS project. Under CO2 leakage conditions, the total plant biomass of tomatoes has almost halved. The tomato fruits grades decreased from moderate to small-grade in the three-level grading system, while the single fruit weight and size significantly decreased. More importantly, the sugar acid ratio of tomatoes declined by 15.95%, from near optimal taste to a sourer taste, leading to a seriously reduced commercial value of tomatoes in response to elevated soil CO2 levels. Our study provides a more quantitative description of the response of tomatoes to CO2 leakage. This will enable carbon capture and storage (CCS) decision-makers to deepen their understanding of CCS safety and associated risk management.

Our testing focuses on the response and impact assessment of vegetables, especially tomatoes, to CCS leakage. From a more comprehensive perspective, in addition to food crops, sugar crops, oilseeds, feed, and fruits widely planted in the field may be affected by CCS project leaks. Future research will focus on further expanding the scope of evaluating plant types and yield quality indicators.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhang, X., Ma, X., Wu, Y., Gao, Q. & Li, Y. A plant tolerance index to select leaking CO2 bio-indicators for carbon capture and storage. J. Clean. Prod. 170, 735–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.180 (2018).

IPCC. Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage. Prepared by Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Dodds, K., Waston, M. & Wright, I. Evaluation of risk assessment methodologies using the in Salah CO storage project as a case history. J. Energy Proc. 4, 4162–4169 (2011).

Sherk, G.W., Romanak, K. D., Gilfillan, S. M., et al. Alleged leakage of CO2 from the Weyburn-Midale CO2 monitoring and storage project: Preliminary finding from implementation of the IPAC-CO2 incident response protocol. C. American geophysical union fall meeting. San Francisco, California: GCCC Digital Publication Series: 11–39. (2011)

Zhang, X. Y., Yin, Z. D., Zhao, Z., Tian, D. & Ma, X. Impacts of leakage of stored CO2 to growth of trifolium hybridum L. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 31, 179–203. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2015.18.028 (2015).

Lakkaraju, V. R. et al. Studying the vegetation response to simulated leakage of sequestered CO2 using spectral vegetation indices. Ecol. Inf. 5, 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2010.05.002 (2010).

Apple, M. E., Sharma, B., Zhou, X. et al. Plants as Indicators of Past and Present Zones of Upwelling Soil CO2 at the ZERT Facility. C. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (2011).

Ko, D., Yoo, G., Seongmilaek, Y. & Chung, H. G. Impacts of CO2 leakage on plants and microorganisms: A review of results from CO2 release experiments and storage sites. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 6, 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/ghg.1593 (2016).

Maček, I., Pfanz, H., Francetič, V., Batič, F. & Vodnik, D. Root respiration response to high CO2 concentrations in plants from natural CO2 springs. Environ. Exp. Botan. 54, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.06.003 (2005).

Ma, X. et al. Assessment on Zea diploperennis L. as bio-indicator of CO2 leakage from geological storage. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 33(18), 224–229 (2017).

Wu, Y., Ma, X., Li, Y. E. & Wan, Y. F. The impacts of introduced CO2 flux on maize/alfalfa and soil. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 23, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2014.02.009 (2014).

Al-Traboulsi, P. et al. The potential impact of CO2 leakage from carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems on growth and yield in spring field bean. Environ. Exp. Botan. 80, 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.02.007 (2012).

Vinha, A. F. et al. Effect of peel and seed removal on the nutritional value and antioxidant activity of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2013.07.016 (2014).

Lu, Z., Wang, J., Gao, R., Ye, F. & Zhao, G. Sustainable valorisation of tomato pomance: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 86, 172–187 (2019).

Amirahmadi, E., Ghorbani, M., Moudry, J., Konvalina, P. & Kopecky, M. Impacts of environmental factors and nutrients management on tomato grown under controlled and open field conditions. Agronomy 13(3), 916 (2023).

Zou, C., Wu, F. & Liu, S. Effect of elevated CO2 concentration on growth, development and photosynthesis of tomato. China Veget. 11, 14–17 (2008).

Yu, C. Y., Du, S. T., Xing, C. H., Lin, X. Y. & Zhang, Y. S. Effects of CO2 concentration on the growth and nutrient uptake of tomato seedlings. J. Zhengjiang Univ. (Agric Life Sci.) 32, 307–312. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1008-9209.2006.03.013 (2006).

Wang, L. G. et al. The effects of increasing CO2 on the growths, yield and nutrient uptake of tomato cultivated in the greenhouse. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 6, 174–181. https://doi.org/10.11838/sfsc.20180625 (2018).

Zheng, J. et al. Elevated CO2 stimulates carbohydrate accumulation in greenhouse tomato fruits. Shanxi Agtic. Univ (Natural Science Edition) 38(8), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.13842/j.cnki.issn1671-8151.201801032 (2018).

Chen, S. C., Zhou, Z. R., He, C. X., Zhang, Z. B. & Yang, X. Rules of CO2 concentration change under organic soil cultivation and effects of CO2 application on tomato plants in solar greenhouse. J. Acta Botanica Boreali-occidentalia Sinica. 24, 1624–1629 (2004).

Wu, Y. et al. Impact assessment and tolerable threshold value of CO2 leakage from geological storage on agro-ecosystem. Trans. CSAE 28, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2012.02.035 (2012).

AOAC: Ascorbic acid. In: Official Methods of Analysis, 967.21, 45.1.14. AOAC International, Gaithersburg (2006).

AOAC: Titratable acidity of fruit products. In: Official Methods of Analysis (17th edn.). 942.15. AOAC International, Gaithersburg (2000).

Rui, W. et al. Dynamic regulation of water deficit on appearance and sugar and acid components of tomato fruit. Acta Agric. Boreali-occidentalis Sin. 32(9), 1356–1364 (2023).

Tengfei, P. et al. Fruit physiology and sugar acid profile of 24 pomelo (Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck) cultivars grown in subtropical region of China. Agronomy 11, 2393 (2021).

Juan, Li. et al. Effects of saline water irrigation on sugar accumulation and activities of sucrose-metabolizing enzymes of greenhouse tomato. J. Northw. A&F Univ. 46(3), 101–110 (2018).

Yeshuo, S., Guoxin, Z., Shoupeng, D., Yutao, Y. & Fengjie, D. Effects of salt stress on flavor compounds of cherry tomato fruits. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 36(4), 0838–0844 (2022).

Xie, G., Xu, R., Chong, L. & Zhu, Y. Understanding drought stress response mechanisms in tomato. Veget Res. https://doi.org/10.48130/vegres-0023-0033 (2024).

Pavithra, S. & Sujatha, K. B. Impact of flooding on growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Int. J. Chem. Stud. 7(4), 2679–2682 (2019).

Feng, P. Y., Chen, S., Zhou, Z. J. & Hu, T. T. Effect of soil water content on titratable acid content in tomato fruits based on rotatable design. J. Northw. A F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Edition) 15, 67–75 (2017).

Tartachnyk, I. & Blanke, M. Photosynthesis and transpiration of tomato and CO2 fluxes in a greenhouse under changing environmental conditions in winter: Research article. Ann. Appl. Biol. 150, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2007.00125.x (2007).

Ji, X. et al. Physiological response of plant millet to simulated carbon capture and storage of CO2 leakage. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 06, 351–356 (2019).

Han, Y., Zhang, X. & Ma, X. Fine root length of maize decreases in response to elevated CO2 level in soil. Appl. Sci. 10, 968 (2020).

Aneta, G. & Katarzyna, H.-K. Tomato tolerance to abiotic stress: A review of most often engineered target sequences. Plant Growth Regul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-017-0251-x (2017).

Acknowledgements

Yu Mengying and Lu Yuzheng helped with this research in the integrated installation and implementation of experimental devices. Thanks to the support of the Shunyi Agricultural Science Experimental Base of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences regarding test conditions.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 32271638 and 32171561), National Key R&D Program of China (No.2023YFF0805904), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (No. BSRF202502), Low Carbon Science Center of the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP- CAAS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, methodology, and writing–original draft preparation; X.Z; conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing–review & editing, X.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Ma, X. Tomato yields and quality declines due to elevated soil CO2. Sci Rep 15, 5689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89830-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89830-3