Abstract

Predicting the medical seriousness, or lethality, of suicide attempts remains challenging for clinicians, as impulsive and planned attempts can both be fatal and risk may vary with age and suicidal intent. We investigated whether attempt lethality is driven by practical preparedness (objective suicidal intent) and/or psychological resolve (subjective suicidal intent) and whether these associations vary with age of onset of suicidal behavior. The study used a cross-sectional lifespan sample (N = 95; age range 16–76 years) with current depression and recent suicidal behavior (≤ 5 years). Linear regression models indicated that older age of onset of suicidal behavior (B = 0.86, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001), and both higher objective intent (B = 0.69, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001) and subjective intent (B = 0.50, SE = 0.20, p = 0.014) were associated with more severe lethality at the most recent attempt, although the association with subjective intent was driven by its shared portion with objective intent. The association between objective intent and lethality was stronger with older age of onset (interaction B = 0.75, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001), whereas the association between subjective intent and lethality was stronger with younger age of onset (interaction B = − 0.42, SE = 0.20, p = 0.036). Our findings suggest that contextualizing suicidal intentions with age of onset, rather than age at the current suicidal crisis, can help clinicians better appraise suicide risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicidal behavior is heterogeneous1. Suicide attempts can be carefully planned or carried out impulsively, and may vary based on the individual’s perceived determination to die. It remains unclear which of the above characteristics contribute most strongly to the risk of more severe, or possibly fatal attempts.

Suicidal intent, defined as ‘an individual’s desire to bring about his or her own death’2, retrospectively captures the tangible and psychological factors immediately preceding an attempt. Under Beck and colleagues’ conceptualization, suicide intent includes both an objective and a subjective dimension3. Objective suicidal intent is a measure of the means and preparedness to attempt (e.g., procuring a weapon or taking precautions to isolate oneself during the act). Subjective intent measures an individual’s sense of their own mental and emotional determination to die by suicide (e.g., psychological resolve to carry out an attempt without hesitation).

While some studies have found a moderate to strong positive relationship between suicidal intent and attempt lethality4,5,6,7, others reported minimal correlation8,9,10 (for reviews2,6,11). These inconsistent findings may arise from considering suicidal intent as a single construct, without examining whether the positive association between intent and lethality is predominantly driven by the objective or subjective dimension of intent.

Of the few studies distinguishing objective from subjective suicidal intent, most tended to conceptualize them in sequence, with suicidal desire (subjective intent) expected to precede suicidal planning (objective intent), in turn preceding suicidal behavior12,13. While the above suicide continuum makes chronological sense, it disregards evidence suggesting that subjective and objective intent may occur concomitantly and diverge in terms of severity and respective contributions to attempt lethality based on the suicidal population examined7.

For instance, associations between subjective and objective intent and attempt lethality may be differentially qualified by age. Evidence suggests that high-lethality attempts in youth tend to correlate with high impulsivity and low objective preparedness, such as planning14 and may be more likely to follow higher levels of subjective intent15, whereas in older adults, limited evidence has linked high-lethality attempts with higher levels of planning6,16.

This age discrepancy may have psychosocial or developmental underpinnings. Younger adults may have a higher number of close social connections compared to older adults17 and form behavioral routines less easily18, contributing to a more varied and unpredictable daily life. Extended periods of time to plan suicidal behavior may be scarcer for younger adults, as their life is influenced by more external and potentially unexpected factors (e.g., receiving rewarding feedback at school or work). Borderline personality disorder, which is characterized by high emotional lability and deficits in planning abilities19, constitutes an important suicide risk factor across the adult life cycle20, although it is more strongly associated with early death21, death by suicide at a younger age22, and generally decreasing clinical severity with age23. Milder clinical indicators of low planning tendencies such as higher impulsive decision-making have also been associated with suicidal behavior in youth24,25. A majority of suicide attempts in young and middle-aged adults have been found to follow initial suicidal desire by sheer minutes or hours13,26,27 and were described by adolescent inpatients as resulting from an opportunistic use of any lethal means at hand to get rid of intense emotional pain28. Consistently, lethal attempts in youth frequently occur with methods requiring minimal preparation, such as firearms29 or falling from a height30,31 and higher attempt lethality in adolescents has been associated with a stronger desire to die32.

In contrast, high-lethality suicide attempts in older adults have been associated with higher levels of planning in addition to a strong desire to die6. Older adults may be more isolated33 and less likely to experience short-term fluctuations in their physical environment, mood, or outlook on life. Hence, at older ages, preparations to attempt suicide may continue uninterruptedly over a longer period. Additionally, suicidal behavior in late life may occur in a population with a more detail-oriented profile than suicidal behavior in early life, as older adults who died by suicide are reported to have more controlling, over-achieving, and obsessive–compulsive personality traits34,35. Taken together, these findings suggest a stronger role of subjective intent compared to objective intent in high-lethality suicide attempts of younger individuals and a stronger role of objective intent compared to subjective intent in high-lethality attempts of older individuals.

It remains nonetheless unclear whether these differences between younger and older individuals with suicidal behavior relate to the age at which they first attempt suicide or their age at the most recent attempt. On one hand, objective intent may become more prominent as individuals who have attempted suicide age, given the concomitant decrease in impulsivity36. Alternatively, older adults with an early onset of suicidal behavior may retain characteristics of younger individuals who have attempted suicide as they age, such as maladaptive decision-making and personality traits37,38,39. This would suggest comparable subjective and objective intent across the early and late suicide attempts of a same individual with multiple attempts, resulting in a stronger association of intent dimensions with age of onset of suicidal behavior than with age at the time of each attempt.

The present cross-sectional study used a sample of 95 adolescents and adults with prior suicidal behavior, who were aged 16–76 years, had a formal diagnosis of major depressive episode, clinically significant current depressive symptoms, and a suicide attempt within the past 5 years. Participants were required to have no history of psychosis or mania, dementia or current clinically significant cognitive deficits, neurological disorders, delirium, recent electroconvulsive therapy, or recent substance abuse or dependence. The study tested the following hypotheses:

(H1)

Both subjective and objective intent are associated with attempt lethality at the most recent attempt.

(H2)

The associations tested under H1 vary with age of onset of suicidal behavior such that the positive association between lethality and objective intent is stronger with older age of onset of suicidal behavior, whereas the positive association between lethality and subjective intent is stronger with younger age of onset of suicidal behavior.

Sensitivity analyses additionally investigated the robustness of the associations found under H1 and H2 to age at the most recent attempt and to physical illness severity, a well-established, age-dependent risk factor for suicidal behavior, which was not accounted for by our sample’s selection criteria40,41.

Results

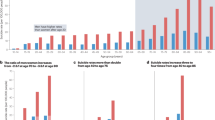

Sample characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The sample comprised 95 participants with depression and suicidal behavior within the past 5 years, ranging from 16 to 76 years of age (mean = 40.4 years, SD = 16.3) and majority female (63%) and White (58%). On average, participants were moderately depressed (HDRS mean = 20.9 points, SD = 6.1) and 86% were experiencing current suicidal ideation (SSI median = 20.5 points, interquartile range = 18.8). Age of onset of suicidal behavior (i.e., age at the first lifetime attempt; range 10–67 years) and age at the most recent attempt (range 14–73 years) spanned from adolescence to old age and were strongly correlated at rho = 0.8 (Fig. 1). Age of onset of suicidal behavior was moderately correlated to physical illness severity at rho = 0.4 (Fig. 1). The range of most recent attempt lethality on the Beck Lethality Scale42 was 0–7 points (where 4 points indicate high lethality), with a mean of 2.6 points (SD = 2.1). Objective and subjective suicidal intent item mean scores measured with the Beck Suicidal Intent Scale3 for the most recent attempt were correlated at rho = 0.4 (Fig. 1).

Spearman correlations between main independent variables of interest. Note: The numbers represent Spearman’s rho, and the shading indicates their magnitude and direction from − 1 (dark red) to 1 (dark blue). Correlation values marked with a star are statistically significant. Age of onset of suicidal behavior corresponds to age at the first lifetime attempt. SIS suicidal intent scale, CIRSG cumulative illness rating scale-geriatric.

(H1)

Both higher objective intent (B = 0.69, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001) and subjective intent (B = 0.50, SE = 0.20, p = 0.014) were associated with higher lethality when tested separately (Table 2, first two columns). When entered in a model together, only the association with objective intent remained significant (B = 0.57, SE = 0.21, p = 0.009; Table 2, third column). Older age of onset of suicidal behavior was associated with higher attempt lethality in all models (B = 0.80–0.91, SE = 0.20–0.21, p < 0.001). Together, the two intent dimensions, age of onset of suicidal behavior, and sex accounted for 28% of the variance of the most recent attempt’s lethality (F(4,89) = 8.58, R2 = 0.28, adjusted R2 = 0.25, p < 0.001).

(H2)

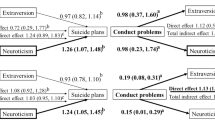

In the interaction model built for H2 (Table 2, last column), positive associations between objective intent and attempt lethality (B = 0.42, SE = 0.20, p = 0.036) and age of onset of suicidal behavior and attempt lethality (B = 0.90, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001) remained present. The association between objective intent and attempt lethality was stronger in participants with an older age of onset of suicidal behavior (interaction B = 0.75, SE = 0.20, p < 0.001; Fig. 2, left panel). By contrast, the association between subjective intent and attempt lethality was stronger in participants with a younger age of onset of suicidal behavior (interaction B = − 0.42, SE = 0.20, p = 0.036; Fig. 2, right panel). Adding these two interactions to the model improved goodness of fit by more than 10% (F(6,87) = 9.40, R2 = 0.39, adjusted R2 = 0.35, p < 0.001).

Objective intent-by-age of onset of suicidal behavior (left panel) and subjective intent-by-age of onset of suicidal behavior (right panel) effects from the main model for H2, predicting lethality of the most recent attempt. Note: Age of onset of suicidal behavior corresponds to the age at the first lifetime attempt. The objective and subjective suicidal intent scores were measured with the corresponding subscales of the Beck suicidal intent scale and suicidal lethality total scores with the Beck lethality scale. Points represent ß^ estimates and bars represent standard errors.

In sensitivity analyses controlling for age at the most recent attempt (Table 3) and physical illness severity (Table 4), all of the above associations remained significant with the exception of subjective intent-by-age of onset of suicidal behavior (resp. B = − 0.12, SE = 0.38, p = 0.753 and B = − 0.36, SE = 0.20, p = 0.075). Neither age at the most recent attempt nor physical illness severity were significant in any model.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study conducted in a lifespan sample of adolescents and adults with depression and a suicide attempt in the past 5 years found that older age of onset of suicidal behavior, and higher objective and subjective intent were associated with higher attempt lethality. However, the association was weaker with subjective intent and driven by its overlap with objective intent. The associations between intent dimensions and lethality were further qualified by age of onset of suicidal behavior, with older age of onset relating to a stronger association between objective intent and attempt lethality and younger age of onset relating to a stronger association between subjective intent and attempt lethality. The effect of age of onset on the association between subjective intent and lethality lost significance after adjusting for age at time of the attempt.

Between the two dimensions of intent, objective intent was associated with attempt lethality more strongly and consistently, which suggests that overall practical preparedness is more closely tied to the seriousness of medical consequences of suicidal behavior than psychological resolve. This aligns with retrospective evidence finding a stronger association of death by suicide with objective intent than with subjective intent43.

Objective intent was particularly strongly associated with attempt lethality when suicidal behavior first occurred at a later age. Individuals who become suicidal in mid- and late life may have better organizational skills, and possibly a more thorough and meticulous personality overall. Trait conscientiousness has been associated with higher suicidal intent severity in the second half of life44 and was higher in older adults who died by suicide compared to older adults surviving a suicide attempt45. Moreover, older adults with an age of onset of suicidal behavior > 50–55 years experienced fewer negative outcomes arising from poor planning throughout their life than their counterparts with early-onset suicidal behavior37 and had a more orderly (i.e., neat, well-organized) personality than same-aged, non-suicidal comparison subjects with depression38.

In contrast, subjective intent had a stronger association with attempt lethality in individuals first attempting at a younger age. Early-onset suicidal behavior and death by suicide at a young age have been linked to more emotionally labile and impulsive personality traits (e.g., high neuroticism or borderline traits38,46,47), impulsive violence14, and more negative life events resulting from acting out and failing to plan ahead37.

Young individuals who engage in suicidal behavior are, by definition, individuals with early-onset suicidal behavior, whereas older individuals who engage in suicidal behavior could be characterized by either early- or later-onset suicidal behavior (as their first attempt could have occurred at any point during their younger or older years). Thus, the distinction between age of onset versus age of the most recent attempt likely bears less importance during youth than later in life and the two age measures are more tightly intercorrelated in younger life. This may also explain why the effect of age of onset on the association between subjective intent and attempt lethality no longer remained significant in our sensitivity analysis controlling for age at time of the attempt.

Yet, age of onset of suicidal behavior retained its significance across all analyses, suggesting that it is capturing relevant information regarding suicidal trajectories that is not reflected in age at the time of most recent attempt, as we have also concluded elsewhere39. This aligns with the findings of a death registry-based study that identified a higher likelihood of having a pre-suicidal plan and signs of physical illness in older adults who died by suicide and did not have a history of past attempts, and more psychiatric disorders, alcohol consumption, and social problems in those who had prior attempts48. In our sensitivity analysis, physical illness severity had a moderate positive correlation with age of onset of suicidal behavior but did not account for its association with attempt lethality. Thus, suicide attempt characteristics, especially later in life, may depend more on whether a given suicidal crisis is a continuation of a certain pattern of suicidal behavior already present earlier in life, wherein risk of lethality may be driven by the intensity of suicidal or self-injurious urges rather than by the extent of practical preparedness or physical illness burden. However, these findings remain to be validated in a broader range of psychiatric conditions, and in different clinical stages within each condition, as clinical stages are also influenced by disease progression. For instance, whereas psychosis and dementia generally increase suicide risk49,50, negative symptoms of psychosis51 and advanced stages of dementia52 may be protective against high-lethality suicidal behavior.

Strengths of this study include the sample’s broad age range, thorough clinical characterization, and recency of suicidal behavior, as well as the nuanced analysis of the relationship between suicidal intent and lethality across the lifespan. Regarding limitations, the cross-sectional design does not allow for making causal inferences or permit a test of our hypotheses in relation to death by suicide. Relying on self-report measures for suicidal behavior characteristics makes it impossible to exclude recall bias, despite the study team’s efforts to corroborate participant accounts with data from medical health records and through collateral history from relatives. Additionally, participants’ depressive states may have further biased their recollection of their past suicide attempt and the affects preceding it53,54. While our sample encompassed participants with clinical levels of depression and a wide age range, it omitted several subpopulations at increased suicide risk, such as individuals with bipolar disorder55, psychosis49, or dementia50, making it unclear whether the study’s results are generalizable to them. Further, our sample size may have limited the detection of certain interaction effects. Finally, we cannot exclude a survival bias, as both younger and older people who died at their first attempt (i.e., who had the highest-lethality attempts) are missing from our sample.

For both researchers and clinicians, it may be surprising that age of onset of the first serious suicidal crisis may influence the association between suicidal intent and lethality. Future research should validate these findings longitudinally, in more diverse psychiatric samples, and test associations between suicidal intent dimensions and individual characteristics varying with age of onset of suicidal behavior, such as personality and problem-solving styles.

Conclusions

From a clinical standpoint, our results emphasize the need to thoroughly assess suicide plans and subjective intent during suicidal crises and contextualize them within the individual suicidal trajectory by also exploring age of onset of suicidal behavior and characteristics of past attempts. Once the relationships between common mental health conditions and subjective and objective suicidal intent is better understood, assessing intent dimensions together with age of onset of suicidal behavior may substantially improve clinical appraisal of suicide risk and offer new avenues for targeted interventions. For instance, safety planning may benefit from considering intent in a dimensional way, as this may help target its subjective or objective dimensions separately (e.g., by addressing hopelessness and negative affects to attenuate psychological resolve vs preventing access to lethal means to decrease practical preparedness).

Methods

Participants

A multi-site sample of 95 individuals aged 16–76 years was recruited from New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, as part of a larger American Foundation for Suicide Prevention funded study. All participants had a history of suicide attempt, defined as a ‘potentially self-injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome [with] evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended at some (nonzero) level to kill himself/herself’56, within the past 5 years. Participants also met criteria for current major depressive episode on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID; First et al.57) and had a score ≥ 14 points on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS, scores > 13 indicate clinical depression; Hamilton58). Exclusion criteria comprised a history of psychosis or mania, a score < 24 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al.59), a current diagnosis of dementia, neurological disorders, or delirium, and electroconvulsive therapy within the past 6 months. Those with current substance abuse or dependence per the SCID were also excluded, however participants remained eligible if abuse or dependence was in remission for longer than 6 months at time of enrollment.

Assessments

Participants’ history of suicidal behavior was assessed, including age and suicide attempt method used at each attempt as well as intent and lethality of their most recent attempt. Trained clinicians used the Columbia Suicide History Form60 to assess suicide attempt history. These data were verified using participant self-report, electronic medical records, and corroboration from family members or close friends.

The Beck Suicide Intent Scale (SIS)3 was used to assess objective and subjective suicidal intent of the most recent attempt. The clinician-administered scale, as originally designed by Beck and colleagues, is comprised of 15 items grouped under two subscales: objective intent (e.g., isolation, precautions against being discovered, consideration of suicide note, practical preparations; Items 1–8) and subjective intent (e.g., expectation of lethality, conception of used method’s lethality, attitude towards living and dying; Items 9–15). All items are scored on a 0–1–2 scale of severity (2 represents maximum severity) and summed.

The Beck Lethality Scale (BLS)42 was employed to assess medical seriousness of the most medically serious and the most recent attempts. The BLS quantifies the medical consequence of an attempt based on the method used. For instance, a lethality score of 4 for an attempt by cutting corresponds to “bleeding of major vessel; danger of considerable blood loss without surgical intervention: suturing necessary but no transfusion; vital areas intact and no change in vital signs; care on outpatient basis”, whereas a score of 4 for an attempt by non-coma-producing drugs corresponds to “some injury (e.g., mouth burns) and treatment in emergency room or on outpatient basis (e.g., gastric lavage)”. If multiple methods are used during a single attempt, the higher-lethality method is considered for the attempt’s lethality score. BLS scores range from 0 (none or minimal medical consequence) to 8 (suicide attempt resulting in death). Any attempt severe enough to require hospitalization is scored ≥ 4 and is considered a high lethality attempt.

As the sample was part of a larger study20, participants underwent a broader demographic and clinical characterization through interview and self-report surveys, which included their age, sex assigned at birth, race, education level, current depression severity (HDRS), and current suicide ideation severity (Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation; SSI)61. Participants’ physical illness severity prior to their most recent suicide attempt was assessed with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRSG), a clinician-administered scale measuring overall physical illness severity as the sum of illness severity scores between 0 (no illness) and 4 (life-threatening, terminal illness) of 13 organ systems, after removal of the 14th, psychiatric system, resulting in a total score between 0 and 52 points62.

Missingness

Of all variables used in our analysis (see Analytic Approach below), the SIS had missing values: one participant failed to complete the subjective intent subscale whereas another had two items missing on the objective intent scale. Hence, item means were used for the SIS in all analysis. The CIRSG was additionally missing in one participant. Missingness of the entire subjective intent subscale and the CIRSG were handled with listwise deletion.

Procedure

The study procedure was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board, and the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant institutional guidelines and regulations. Participants were recruited via advertisements posted on public transport, at primary care practices, as well as inpatient and outpatient psychiatric clinics and units.

After providing written informed consent, participants underwent the sociodemographic, suicidal, and psychiatric characterization outlined above.

Analytic approach

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.1). Linear regression models predicting lethality at the most recent attempt and covarying for sex and age of onset of suicidal behavior tested whether (H1) objective and subjective intent were associated with attempt lethality in separate models, and when entered in the model together to factor out their shared variance. We then tested (H2) whether the associations between objective and subjective intent further varied with age of onset of suicidal behavior by entering age of onset in interaction with objective and subjective intent within the same model. In a first set of sensitivity analyses ensuring that the observed results were specific to age of onset, each significant effect was further tested in models covarying for age at the most recent attempt. To avoid unreasonably increasing the risk of multicollinearity, the robustness of objective intent-by-age of onset and subjective intent-by-age of onset interactions to, respectively, objective intent-by-age at the most recent attempt and subjective intent-by-age at the most recent attempt were tested in separate models. In a second set of sensitivity analyses, main findings were tested after including physical illness severity as a covariate, given the age-moderated association between physical illness and first onset of suicidal behavior reported in population surveys40,41. Variance inflation factors in the main models were < 2, and < 3.7 in all sensitivity analyses.

Data availability

Data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Szanto, K., Galfalvy, H., Vanyukov, P. M., Keilp, J. G. & Dombrovski, A. Y. Pathways to late-life suicidal behavior: Cluster analysis and predictive validation of suicidal behavior. J. Clin. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11611 (2018).

Hasley, J. P. et al. A review of “suicidal intent” within the existing suicide literature. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 38, 576–591 (2008).

Beck, A. T., Schuyler, D. & Herman, I. Development of suicidal intent scales. In The Prediction of Suicide (eds Beck, A. T. et al.) 45–56 (Charles Press Publishers, 1974).

Horesh, N., Levi, Y. & Apter, A. Medically serious versus non-serious suicide attempts: Relationships of lethality and intent to clinical and interpersonal characteristics. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 286–293 (2012).

Kumar, C. T., Mohan, R., Ranjith, G. & Chandrasekaran, R. Characteristics of high intent suicide attempters admitted to a general hospital. J. Affect. Disord. 91, 77–81 (2006).

Barker, J., Oakes-Rogers, S. & Leddy, A. What distinguishes high and low-lethality suicide attempts in older adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 154, 91–101 (2022).

Sahoo, A., Swain, S. P. & Kar, N. Personality dimension, suicidal intent, and lethality: A cross-sectional study of suicide attempters with or without personality disorders. Indian J. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176241287161 (2024).

Brown, G. K., Henriques, G. R., Sosdjan, D. & Beck, A. T. Suicide intent and accurate expectations of lethality: Predictors of medical lethality of suicide attempts. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 72, 1170 (2004).

Plutchik, R., van Praag, H. M., Picard, S., Conte, H. R. & Korn, M. Is there a relation between the seriousness of suicidal intent and the lethality of the suicide attempt?. Psychiatry Res. 27, 71–79 (1989).

Yang, H.-J., Jung, Y.-E., Park, J. H. & Kim, M.-D. The moderating effects of accurate expectations of lethality in the relationships between suicide intent and medical lethality on suicide attempts. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 20, 180–184 (2022).

Liotta, M., Mento, C. & Settineri, S. Seriousness and lethality of attempted suicide: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 21, 97–109 (2015).

Marie, L., Poindexter, E. K., Fadoir, N. A. & Smith, P. N. Understanding the transition from suicidal desire to planning and preparation: Correlates of suicide risk within a psychiatric inpatient sample of ideators and attempters. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 159–166 (2020).

Paashaus, L. et al. From decision to action: Suicidal history and time between decision to die and actual suicide attempt. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 28, 1427–1434 (2021).

Brent, D. A. et al. Personality disorder, personality traits, impulsive violence, and completed suicide in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 33, 1080–1086 (1994).

Sapyta, J. et al. Evaluating the predictive validity of suicidal intent and medical lethality in youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 80, 222–231 (2012).

Conwell, Y. et al. Age differences in behaviors leading to completed suicide. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 6, 122–126 (1998).

Antonucci, T., Akiyama, H. & Takahashi, K. Attachment and close relationships across the life span. Attach. Hum. Dev. 6, 353–370 (2004).

Van De Vijver, I., Brinkhof, L. P. & De Wit, S. Age differences in routine formation: The role of automatization, motivation, and executive functions. Front. Psychol. 14, 1140366 (2023).

Bazanis, E. et al. Neurocognitive deficits in decision-making and planning of patients with DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder. Psychol. Med. 32, 1395–1405 (2002).

Buerke, M. et al. Age effects on clinical and neurocognitive risk factors for suicide attempt in depression—Findings from the AFSP lifespan study. J. Affect. Disord. 295, 123–130 (2021).

Temes, C. M., Frankenburg, F. R., Fitzmaurice, G. M. & Zanarini, M. C. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 80, 4039 (2019).

Broadbear, J. H., Dwyer, J., Bugeja, L. & Rao, S. Coroners’ investigations of suicide in Australia: The hidden toll of borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 129, 241–249 (2020).

Álvarez-Tomás, I., Ruiz, J., Guilera, G. & Bados, A. Long-term clinical and functional course of borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Psychiatry 56, 75–83 (2019).

MacPherson, H. A. et al. Cognitive flexibility and impulsivity deficits in suicidal adolescents. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 50, 1643–1656 (2022).

McHugh, C. M. et al. Impulsivity in the self-harm and suicidal behavior of young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 116, 51–60 (2019).

Deisenhammer, E. A. et al. The duration of the suicidal process: How much time is left for intervention between consideration and accomplishment of a suicide attempt?. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 19–24 (2009).

Kattimani, S., Sarkar, S., Menon, V., Muthuramalingam, A. & Nancy, P. Duration of suicide process among suicide attempters and characteristics of those providing window of opportunity for intervention. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 7, 566–570 (2016).

Almeida, J., Barber, C., Rosen, R. K., Nicolopoulos, A. & O’Brien, K. H. M. “In the moment I wanted to kill myself, and then after I didn’t”: A qualitative investigation of suicide planning, method choice, and method substitution among adolescents hospitalized following a suicide attempt. Youth Soc. 55, 29–43 (2023).

McKean, A. J. S., Pabbati, C. P., Geske, J. R. & Bostwick, J. M. Rethinking lethality in youth suicide attempts: First suicide attempt outcomes in youth ages 10 to 24. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 57, 786–791 (2018).

Im, J.-S. et al. Proximal risk factors and suicide methods among suicide completers from national suicide mortality data 2004–2006 in Korea. Compr. Psychiatry 52, 231–237 (2011).

Lin, J.-J. & Lu, T.-H. Suicide mortality trends by sex, age and method in Taiwan, 1971–2005. BMC Public Health 8, 6 (2008).

Nasser, E. H. & Overholser, J. C. Assessing varying degrees of lethality in depressed adolescent suicide attempters. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 99, 423–431 (1999).

Luhmann, M. & Hawkley, L. C. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Dev. Psychol. 52, 943–959 (2016).

Harwood, D., Hawton, K., Hope, T. & Jacoby, R. Psychiatric disorder and personality factors associated with suicide in older people: A descriptive and case-control study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16, 155–165 (2001).

Kjølseth, I., Ekeberg, O. & Steihaug, S. ‘Why do they become vulnerable when faced with the challenges of old age?’ Elderly people who committed suicide, described by those who knew them. Int. Psychogeriatr. 21, 903–912 (2009).

Hopwood, C. J. & Zanarini, M. C. Borderline personality traits and disorder: Predicting prospective patient functioning. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78, 585 (2010).

Perry, M. et al. A lifetime of challenges: Real-life decision outcomes in early-and late-onset suicide attempters. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 4, 100105 (2021).

Szücs, A., Szanto, K., Wright, A. G. C. & Dombrovski, A. Y. Personality of late- and early-onset elderly suicide attempters. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 35, 384–395 (2020).

Szanto, K., Szücs, A., Kenneally, L. & Galfalvy, H. Is late-onset suicidal behavior a distinct subtype?. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2023.12.007 (2023).

Scott, K. M. et al. Chronic physical conditions and their association with first onset of suicidal behavior in the world mental health surveys. Psychosom. Med. 72, 712–719 (2010).

Onyeka, I. N., Maguire, A., Ross, E. & O’Reilly, D. Does physical ill-health increase the risk of suicide? A census-based follow-up study of over 1 million people. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29, e140 (2020).

Beck, A. T., Beck, R. & Kovacs, M. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am. J. Psychiatry 132, 285–287 (1975).

Harriss, L. & Hawton, K. Suicidal intent in deliberate self-harm and the risk of suicide: The predictive power of the suicide intent scale. J. Affect. Disord. 86, 225–233 (2005).

Szücs, A. et al. Diligent for Better or Worse: Trait Conscientiousness in Suicidal Ideation and Behavior and Its Moderating Effect on Ageing [Poster Presentation] (Society of Biological Psychiatry, 2023).

Tsoh, J. et al. Attempted suicide in elderly Chinese persons: A multi-group, controlled study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 13, 562–571 (2005).

May, A. M., Klonsky, E. D. & Klein, D. N. Predicting future suicide attempts among depressed suicide ideators: A 10-year longitudinal study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46, 946–952 (2012).

May, A. M. & Klonsky, E. D. What distinguishes suicide attempters from suicide ideators? A Meta-analysis of potential factors. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 23, 5–20 (2016).

Ho, R. C. M., Ho, E. C. L., Tai, B. C., Ng, W. Y. & Chia, B. H. Elderly suicide with and without a history of suicidal behavior: Implications for suicide prevention and management. Arch. Suicide Res. 18, 363–375 (2014).

Sicotte, R., Iyer, S. N., Kiepura, B. & Abdel-Baki, A. A systematic review of longitudinal studies of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in first-episode psychosis: Course and associated factors. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 56, 2117–2154 (2021).

Erlangsen, A. et al. Association between neurological disorders and death by suicide in Denmark. JAMA 323, 444 (2020).

Huang, X., Fox, K. R., Ribeiro, J. D. & Franklin, J. C. Psychosis as a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Med. 48, 765–776 (2018).

Conejero, I. et al. A complex relationship between suicide, dementia, and amyloid: A narrative review. Front. Neurosci. 12, 371 (2018).

Colombo, D. et al. Exploring affect recall bias and the impact of mild depressive symptoms: An ecological momentary study. In Pervasive Computing Paradigms for Mental Health (eds Cipresso, P. et al.) 208–215 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25872-6_17.

Kriesche, D., Woll, C. F. J., Tschentscher, N., Engel, R. R. & Karch, S. Neurocognitive deficits in depression: A systematic review of cognitive impairment in the acute and remitted state. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 273, 1105–1128 (2023).

Serra, G. et al. Suicidal behavior in juvenile bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 311, 572–581 (2022).

O’Carroll, P. W. et al. Beyond the tower of babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 26, 237–252 (1996).

First, M. Sr., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). Version 2.0. (1995).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23, 56–62 (1960).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Posner, K. et al. The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1266–1277 (2011).

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M. & Weissman, A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicide ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 47, 343–352 (1979).

Miller, M. D. et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: Application of the cumulative illness rating scale. Psychiatry Res. 41, 237–248 (1992).

Funding

This work was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [LSRG-0–007–13 to JGK, JAB, and KSz] as well as the National Institute of Mental Health [R01MH085651 to KSz], and by internal funds to the National University of Singapore: Division of Family Medicine Research Capabilities Building Budget [NUHSRO/2022/049/NUSMed/DFM].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, and project administration: JK, JB, KSz; supervision: KSz, HG, AM; methodology: AS, MPF, HG, AM, and KSz; formal analysis: AS, MPF, data curation: MPF, EO; writing—original draft: AS, MPF, and EO; writing—review and editing: JB, JK, AM, HG, and KSz.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szücs, A., Perry-Falconi, M.A., O’Brien, E.J. et al. Objective and subjective suicidal intent are differentially associated with attempt lethality based on age of onset of suicidal behavior. Sci Rep 15, 5621 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89844-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89844-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Characterizing suicidal intent among suicidal adolescents: a systematic review

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health (2026)

-

Age matters: a narrative review and machine learning analysis on shared and separate multidimensional risk domains for early and late onset suicidal behavior

Neuropsychopharmacology (2026)