Abstract

Coal mining is a typical high-risk industry, and the unsafe behavior of miners is the main reason for the high incidence of coal mining accidents. To prevent and control miners’ group unsafe behavior, a research method combining survey design, Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA), and Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) was used to explore the combined effects of multiple antecedent variables of group unsafe behavior and their complex causal relationships with outcomes from the perspectives of group dynamics and institutional environment. The results showed that individual group dynamics or institutional environmental factors do not constitute necessary conditions for group unsafe behavior among miners, but multiple equally effective causal configurations exist. High unsafe behavior among miner groups can be categorized into four types: multidimensional suppression type, lack of safety goals under high-pressure type, lack of safety culture under high-pressure type, and scattered type. Non-high unsafe behavior among miners can be categorized into two kinds: unity and cooperation, as well as cohesion, goal, and culture-driven behavior. The causal paths of high and non-high unsafe behavior exhibit asymmetry. The most influential path leading to high unsafe behavior among miner groups was configuration 1, which was ~ GC1 × ~ GC2 × ~ GPS × ~ GSO × ~ GSC; configuration 6b, which was GC1 × ~ GP × GPS × GSO × GSC, was the most effective in suppressing high unsafe behavior among miner groups, with a raw coverage rate of 0.444. Based on the results, intervention measures were proposed to address the key predictors of high unsafe behaviors in miners’ groups. The study accurately identifies the grouping paths of “high unsafe behaviors” and “non-high unsafe behaviors” in the miners’ group, providing new avenues for mine safety management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the future, coal will remain the global energy backbone1, crucial for improving the national level of sustainable energy security2. However, the coal industry has always been classified as high-risk due to its frequent accidents and susceptibility, posing severe challenges to safety production3,4. Statistics showed that over 90% of coal mine production safety accidents were directly related to unsafe human behavior5,6. Research on miner unsafe behavior is a classic issue in the field of safety management, and how to prevent and control miner unsafe behavior is one of the major challenges that urgently need to be overcome for coal mine safety production to enter the “tough stage”.

Coal mine enterprises in China are labor-intensive enterprises, and front-line workers in coal mines are usually divided into squads and teams, with groups holding a dominant position in coal mining enterprises. Once unsafe behavior of team individuals forms, they are easily imitated and learned by other miners. Under appropriate conditions, they can spread, accumulating and aggregating unsafe behavior, resulting in a “herd effect” that ultimately triggers accidents7,8. According to group dynamics theory9, miners’ unsafe behavior was influenced by a combination of the group’s intrinsic needs and environmental factors, leading to behavior different from those exhibited when individuals were alone. The occurrence of miners’ unsafe behavior is a complex system with multiple interacting factors10. The mechanism behind group unsafe behavior is complex and variable, with the antecedent variables having mutual coupling11. Therefore, it is important to strengthen research on the antecedent variables of group unsafe behavior among miners and explore the pathways through which group unsafe behavior is formed by coupling multiple factors.

Currently, many scholars have studied unsafe behaviors among miners, and existing research has enriched the theoretical and practical applications in the field of safety behaviors, thereby improving unsafe behaviors in the workplace. However, there are still the following deficiencies: On one hand, most of the existing literature explores the influence mechanisms of unsafe behavior from the perspective of individual miners, leaving a gap in the research on the impact and prediction of unsafe behaviors among miners groups from the perspectives of group dynamics and institutional environment. On the other hand, few scholars have analyzed the causal paths and core conditions of unsafe behaviors among miner groups using configurational approaches. Traditional quantitative analysis methods, such as correlation and multiple regression analysis, ignored the causal asymmetry assumptions of set-theoretic relationships. Research on unsafe behaviors among miner groups often focuses on analyzing the linear impact of variables on outcomes, lacking the use of scientific research methods to analyze the complex mechanisms produced by the coupling effects of variables. In summary, the issue of how to effectively inhibit unsafe behaviors among miner groups has not yet been effectively resolved.

This study addresses the practical issue of “what antecedent conditions lead to unsafe behaviors among mining groups”. Utilizing the Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) calculation method and the management paradigm fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) method to characterize situational features based on configuration logic from the perspectives of group dynamics and institutional environment. Combining various antecedent conditions, a configuration analysis framework for miner group unsafe behavior was constructed to seek pathways to inhibit these behaviors. Through a series of studies, the research aims to answer the following questions: (1) What are the antecedent conditions of miner group unsafe behavior? (2) How to construct configuration pathways for “high unsafe behavior” and “non-high unsafe behavior” among miner groups? (3) How we break the limitations of traditional linear regression methods, adapt to the complexity of current group unsafe behavior, and derive high objective predictive conclusions based on statistical information configuration methods?

The theoretical contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) Research perspective: This study, based on configurational theory and group dynamics theory, delves into the synergistic interaction mechanisms of six important antecedent conditions at the levels of group dynamics and institutional environment. This helps to unveil the “black box” of how group dynamics and institutional environments influence unsafe behaviors among miner groups, thereby providing coal mining enterprises with more precise safety management strategies. (2) Research methodology: By considering the causes of unsafe behaviors among miner groups from multiple angles, this study introduces methods from the field of management into the domain of coal mine safety. It employs Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) and the configurational research method of fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to clarify the sufficiency relationships between unsafe behaviors among miner groups and various configurations. This achieves a good combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis, offering new research ideas and methods to explain complex causal relationships such as asymmetry and concurrency in the study of unsafe behaviors among miner groups.

Theoretical basis

This paper conducted research based on configuration theory and group dynamics theory. Configuration theory focuses on the relationships and interactions among elements to reveal the deep mechanisms of system behavior. It serves as a theoretical framework for understanding and studying the interrelationships among various elements in complex systems, providing a powerful tool for comprehending complex systems12. Group dynamics theory, on the other hand, suggests that from the perspective of the group, individual behavior can change based on the influence exerted by the group. In reality, the miner group is relatively closed and stable, making their behavior easily influenced by inter-group factors9. Therefore, applying group dynamics theory to study unsafe behaviors among miner groups holds significant importance.

Precursor factors at the group dynamics level affecting unsafe behaviors among miners

Existing research has indicated that compared to individual factors, group factors have a more significant impact on miners’ unsafe behavior13. Individuals exist depending on the group, and behavior is influenced by the group14,15. Lv et al.16 analyzed the safety behavior risks of miner groups based on evolutionary game theory and provided specific intervention strategies. Li et al.17 qualitatively simulated the safety behavior of miner groups based on qualitative simulation techniques and optimization software platforms and derived the evolutionary laws of group safety behavior. Deng et al.18 explored group cognition of unsafe behavior among construction workers from individual factors and proposed personalized management strategies. Currently, research on group unsafe behavior is still in its early stages19. In the study of antecedents of group dynamics, Leve et al.20 examined Janis’ “group-think social identification maintenance” theory from the aspects of threat, group cohesion, and group efficacy, demonstrating the practicality of group-think theory. Farh et al.21 explored the joint impact of group efficacy and gender diversity on group cohesion and group performance. Lo et al.22 proposed that emotional contagion would lead to normal or abnormal group behavior and simulated the dynamics of emotional contagion between groups based on a cellular automaton approach. Quan et al.23 constructed a dual-layer network model to explore the issue of emotional contagion among passenger groups in large-scale flight delays, enhancing the relevant management departments’ early warning of collective events. Shen et al.24 believed that stress can indirectly influence the unsafe behavior of construction workers through cognition.

Precursor factors at the institutional environment level affecting unsafe behaviors among miners

Existing research has found that factors influencing unsafe behavior can be divided into individual, organizational, and environmental factors, with organizational factors being the most important25,26. Shrivastava et al.27 analyzed the Indian mining industry based on questionnaire surveys and found that management factors play a partial mediating role between geological and operational factors. A people-oriented safety culture can significantly enhance miners’ compliance with company rules and regulations, reduce group unsafe behavior, and thereby reduce the occurrence of coal mine accidents28. For example, Zohar et al.29 constructed a group-level model of safety climate and examined the impact of group safety climate on accidents in the manufacturing industry. Kapusta et al.30 proposed that safety culture is an important factor influencing organizational culture in mining companies and conducted a study on the level of safety culture in Polish mining companies based on questionnaire surveys.

Prediction of precursor factors at the levels of group dynamics and institutional environment

Li et al.31 pointed out that before a coal mine enters an unsafe risk state, the changing trends of the main factors influencing coal mine risk should be analyzed and predicted. Jing et al.32 predicted elevator workers’ safety behavior and accidents based on personality factors and safety attitudes. Using a cross-sectional questionnaire survey method, Pienaar et al.33 predicted miners’ safety compliance based on antecedent variables such as job stress, job insecurity, job satisfaction, and safety commitment. The studies of these scholars have demonstrated that predicting influencing factors is feasible and necessary.

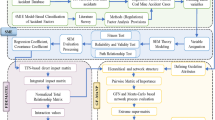

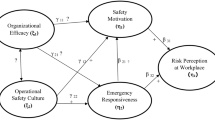

This paper combined group dynamics and institutional environment to explore the configurational synergy mechanism of group unsafe behaviors. The research framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Scale design

This study drew on established scales both domestically and internationally, referencing the construction workers’ motivation scale by Fu et al.34 and the group stress scale by Steijn et al.35, as well as items from Lowe et al.36, combined with the specific work situations of frontline miners and the characteristics of team members, the scale items were developed. After the scale was prepared, the items were revised through interviews with relevant experts and scholars to form a formal questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was prepared using Likert’s 5-point scale method, where a higher value indicates a higher level of agreement with the item. The questionnaire consists of three parts: questionnaire instructions, basic information, and main section. The main section includes three dimensions: group dynamics, institutional environment, and group unsafe behavior among miners. The group dynamics dimension comprises four variables: group cohesion, group contagion, group pressure, and group psychological safety. Each variable has four questions. For example, an item from the group cohesion scale was: “The group I belong to shares common security objectives”. The institutional environment dimension includes group safety culture and group safety objectives. Two items were set for group safety objectives, such as “The group of coworkers I belong to has comprehensive safety behavior reference standards”. Three items were set for group safety culture, such as “The safety regulations of the group I belong to are well-established and effectively enforced”. The group unsafe behavior dimension includes five items, such as “I sometimes learn to imitate the unsafe behaviors of others”. The detailed scale is provided in the appendix.

Data collection

This study utilized a structured questionnaire based on the measurement scale to collect data. The survey targeted over 200 front-line team members from coal mining companies in Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia in China. The research period spanned from June 2023 to August 2024. Front-line miners in coal companies typically work underground in team formations, with common team types including comprehensive mining teams, tunneling teams, electromechanical teams, conveyor belt transport teams, and ventilation and safety teams. Focusing on front-line team members in coal mining as the subjects of this study to investigate miners’ group unsafe behaviors was justified and reasonable. A combination of online and paper questionnaires was used for data collection. At the start of the survey, participants were informed that the survey was anonymous, and miners’ privacy was protected. Additionally, they received a brief survey invitation letter explaining the purpose, risks, and relevant questions of the study. In the third part of the questionnaire, each variable was briefly explained to help participants understand the meaning of each variable. Finally, a total of 200 questionnaires were collected in this study. After excluding questionnaires that did not meet the requirements, 185 valid questionnaires were retained, resulting in an effective response rate of 92.5%. All methods in this study were conducted by relevant guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institute of Safety and Emergency Management at Xi’an University of Science and Technology. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardians.

Data statistics and analysis

Reliability analysis

Due to the adoption of a mature scale, the data analysis mainly considered the reliability analysis of the scale. The analysis included the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and the number of items for the six independent variables of group cohesion, group contagion, group pressure, group psychological safety, group safety goals, and group safety culture, as well as the overall scale. The results are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, the overall Cronbach’s Alpha value of the scale was 0.833 (Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.7). The Alpha values for the seven dimensions—group cohesion, group appeal, group pressure, group psychological safety, group safety goals, group safety culture, and group unsafe behavior—were 0.810, 0.784, 0.798, 0.768, 0.857, 0.875, and 0.923, respectively. Moreover, removing any item results in Alpha values for the 26 items being less than their respective dimensional Alpha values, which would reduce the scale’s overall reliability. This indicated that the 26 items in the scale should not be deleted, and the internal consistency of the scale was good.

Common method bias analysis

Common method bias refers to the extent of artificial error caused by data measurement or systematic procedures, which may bias empirical research. Considering that sample data collected might have common method bias when all variables in the study were measured in the same way, this study employed three methods to avoid it. First, data from multiple sources, such as text records and field visits, were used to verify the scale data, thereby reducing the influence of common method bias. Second, reverse questions, such as questions in the “group pressure” dimension, were added to the scale to reduce respondents’ habitual responses. Third, the Harman single-factor method was used to test for common method bias. If the variance explained by the first factor exceeds the 50% threshold, it indicates the presence of common method bias. Conversely, if it is below 50%, the common method bias is considered acceptable.

This paper conducted an exploratory factor analysis on each antecedent condition, extracting six principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1. The largest principal component explained 40.763% of the total variance, which was below the 50% critical threshold. Therefore, it indicated that the common method bias in this study was within an acceptable range and would not affect subsequent empirical research.

fsQCA combined with NCA

The NCA method was proposed by Professor Dul in 201637, where necessary conditions refer to the prerequisite conditions and elements required to achieve a certain result. Without such prerequisites, the specific result cannot be achieved. The NCA method mainly analyzes the impact size and bottleneck level of antecedents, quantitatively and visually displaying the level of antecedent conditions required to achieve a certain level of the result variable. The fsQCA method was introduced by Professor Ragin in 198738, based on set theory, Boolean algebra, and configuration thinking, it can analyze “multiple simultaneous causal relationships”. The fsQCA method aims to explore the relationships between individual antecedent conditions, combinations of antecedent conditions, and outcomes, explaining the complex causal relationships behind phenomena, and being able to draw predictive conclusions based on the configuration of statistical information39,40. The combination of NCA and fsQCA methods has been widely used in research on the outcomes of multiple antecedent conditions and fsQCA method has also been used in studies of the prediction of influencing factors41,42.

The unsafe behavior of miners has characteristics of mutual influence, high risk, and complex correlation. This study brought the configuration perspective into the analysis of group unsafe behavior of miners, using the NCA method to more accurately assess bottleneck standards for group unsafe behavior and applying the fsQCA method to analyze the pathways for enhancing group unsafe behavior prediction. By combining the two methods, the study aims to explore the configuration interactive effects of group dynamics and institutional environmental factors on group unsafe behavior.

Results

Variables calibration

Before conducting a necessity and sufficiency analysis, it is necessary to calibrate the antecedent and outcome variables. In this study, there were two types of data: group unsafe behavior data as binary data, and the 0–1 calibration method was used, with group unsafe behavior assigned a value of 1 and group safe behavior assigned a value of 0, by the subordination relationship43. The calibration of the antecedent conditions of unsafe behavior used the direct calibration method, with the 95th percentile, median, and 5th percentile of the sample descriptive statistics of the antecedent conditions and outcomes set as anchor points for complete subordination, intersection, and complete non-subordination, respectively. Additionally, to avoid the configuration attribution problem where the case subordination of the antecedent conditions exactly matches the anchor points, a constant of 0.001 was subtracted from the anchor subordination44. The set, calibration, and descriptive statistics of the scale are shown in Table 2.

Necessary condition analysis by NCA

This study comprehensively used two estimation methods, Ceiling Regression (CR) and Ceiling Envelopment (CE), to calculate the effect size. According to Du44, when the effect size d was less than 0.1, the variable had a low effect on the outcome; when 0.1 < d < 0.3, the variable had a moderate effect on the outcome; when the effect size d was greater than 0.3, the variable had a high effect on the outcome. The results of the necessity analysis for individual conditions in NCA are shown in Table 3.

The analysis results from Table 3 indicated that the necessary effects of group cohesion and group contagion were not significant (p > 0.05), suggesting that these two conditions alone do not constitute necessary conditions for group unsafe behavior. While the necessary effects of group pressure, group psychological safety, group safety objectives, and group safety culture were significant, their effect sizes were small (d < 0.1), indicating that they also do not constitute necessary conditions for group unsafe behavior.

The pathway of high-risk behavior was obtained to further analyze the bottleneck level of NCA for individual conditions, and bottleneck level analysis was conducted as shown in Table 4.

According to Table 4, when the high unsafe behavior level reached 100%, it required a 44.9% level of group cohesion, a 67.2% level of group contagion, a 44.9% level of group pressure, a 64.0% level of group psychological safety, an 82.4% level of group safety objectives, and an 81.0% level of group safety culture.

Necessary condition analysis by fsQCA

To further validate the necessity of single variables, the calibrated data were input into the fsQCA 3.0 software to obtain the level of consistency and coverage of each antecedent variable as a necessary condition for the unsafe behavior of a group of miners. According to Fiss et al.45 research, when the consistency level was greater than 0.9, the variable constituted a necessary condition for the outcome variable. The fsQCA analysis results are shown in Table 5.

From Table 5, it can be observed that the consistency level of group pressure was the highest at 0.742, indicating that it does not constitute a necessary condition for the outcome variable. The consistency levels of the antecedent variables were all below 0.7, suggesting that the necessity of each antecedent variable was at a relatively low level. Therefore, this study needed to combine multiple antecedent conditions for a configuration analysis.

Conditional configuration analysis

Based on variable calibration and single variable necessary condition analysis, a configuration analysis was conducted using the fsQCA 3.0 software to explore the multiple causal relationships leading to unsafe behavior in mining groups. The number of cases was set to 1, and the consistency threshold was set at 0.80. When the Proportional Reduction in Inconsistency (PRI) exceeded 0.6, it was coded as 1, and when it was less than 0.6, it was coded as 0. By considering the similarity of core conditions in each configuration path, the unsafe behavior in mining groups was classified. The table after classification is shown in Table 6.

; the absence of the core condition is indicated by

; the absence of the core condition is indicated by  ; the presence of the edge condition is indicated by

; the presence of the edge condition is indicated by  ; the absence of the edge condition is indicated by

; the absence of the edge condition is indicated by  ; blank indicates that the condition is optional.

; blank indicates that the condition is optional.Using consistency and coverage as criteria, we assessed whether combinations of antecedent conditions effectively explain the outcome variable. Consistency refers to the degree of match between a specific combination of conditions and the outcome. Raw coverage denotes the direct explanatory power of cases covered by a particular combination of conditions. Unique coverage indicates the degree of unique association between a specific combination of conditions and the outcome, among all combinations. Overall consistency represents the sufficiency of all configurations in affecting the outcome. Overall coverage indicates the extent to which all configurations explain the outcome. According to Table 6, the configuration analysis results for high unsafe behavior in mining groups included 6 different condition configurations. Among them, the configuration causing the highest level of unsafe behavior in mining groups was configuration 1, which was ~ GC1 × ~ GC2 × ~ GPS × ~ GSO × ~ GSC, with a raw coverage of 0.440. For the configuration analysis results of non-high unsafe behavior in groups, there were 3 configurations. The configuration 6b, GC1 × ~ GP × GPS × GSO × GSC, was the most effective in suppressing high unsafe behavior in mining groups, with the highest raw coverage of 0.444. It was generally considered that when the overall consistency reached 0.8 and the overall coverage reached 0.5, the obtained solution had good explanatory power. In this study, the overall consistency reached 0.820 and the overall coverage reached 0.586. Moreover, the consistency levels of each configuration were greater than 0.8, indicating that the interpretability of each configuration was at a high level, meeting the research requirements.

Robustness test

This study conducted a robustness test on the configuration pathways of the antecedents of high-risk behavior among miners46. First, the consistency threshold was raised from 0.80 to 0.85, while other parameter settings remained the same, resulting in no significant changes in the analysis results of the configuration pathways, consistency levels, and coverage levels. Second, increasing PRI from 0.60 to 0.70 with other parameter settings unchanged also did not result in significant changes in the analysis results. Therefore, it can be concluded that the analytical results of this study passed the robustness test, and the conclusions of the study are reliable and scientific.

Discussion

Configuration analysis of high unsafe behavior in miner groups

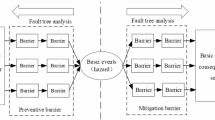

Table 6 showed the results of the configuration analysis, indicating that there were 6 pathways of influence on high unsafe behavior among miners (Configuration 1, Configuration 2a, Configuration 2b, Configuration 3a, Configuration 3b, and Configuration 4). The consistency values for these pathways were 0.828, 0.923, 0.939, 0.909, 0.893, and 0.917 respectively, all above 0.800. The overall consistency was 0.820, suggesting that all 6 pathways were sufficient conditions for the formation of high unsafe behavior among miners. When these 6 configurations were met, 82% of miners exhibited group unsafe behavior, demonstrating the validity of the research results. The core conditions of Configuration 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b were the same, forming a second-order equivalent configuration45, merged into one category. Following the principle of simplicity in configuration naming, the 6 paths of influencing factors leading to high unsafe behavior in mining communities were named multidimensional suppression type (Configuration 1), lack of safety culture under high-pressure type (Configuration 2a and 2b), lack of safety goals under high-pressure type (Configuration 3a and 3b), and scattered type (Configuration 4) based on the core conditions of high unsafe behavior in mining communities. To present the analysis results more clearly, a configuration path diagram was used to visually display the 6 pathways of high unsafe behavior among miners, as shown in Fig. 2.

-

(1)

Multidimensional suppression type (Configuration 1): Configuration 1 indicated that a combination of core conditions including low group cohesion, low group psychological safety, low group safety objectives, and low group safety culture, with low group contagion as a marginal condition, was sufficient to form high unsafe behavior in mining communities. The raw coverage of this configuration was 0.440, and the unique coverage was 0.210, indicating that 44 individuals can be explained by this configuration. As Lo et al.22 proposed, emotional contagion can lead to normal or abnormal group behavior. It can be seen that if the core conditions are met, emotional contagion as a boundary condition will lead to abnormal group behavior, namely high unsafe behavior among miners. On the other hand, if the core conditions are not met, emotional contagion will lead to normal group behavior among miners, that is, non-high unsafe behavior among miners.

-

(2)

Lack of safety culture under high-pressure type (Configuration 2a and 2b): Configuration 2a showed a consistency of 0.923 and a unique coverage of 0.019. In this configuration, high group cohesion, high group pressure, and low group safety culture played core roles, while low group psychological safety and low group safety objectives played supporting roles, with group contagion being irrelevant. Configuration 2b (GC1 × ~ GC2 × GP × GPS × GSO × ~ GSC) had a consistency of 0.939 and a unique coverage of 0.022. In this configuration, the presence of high group cohesion, high group pressure, and low group safety culture collectively played core roles, while low group contagion, high group psychological safety, and high group safety objectives played supporting roles. Comparing Configuration 2a and 2b, it was evident that high group pressure has a much greater impact on high unsafe behavior in mining communities compared to group cohesion. Previous studies, such as by Huan. et al.47, have pointed out that miners’ work stress was one of the important causes of serious mine accidents in China. Furthermore, reducing work pressure was a long-term task that required the joint participation of employees, managers, and government departments. It was consistent with the findings of this paper.

-

(3)

Lack of safety goals under high-pressure type (Configuration 3a and 3b): Configuration 3a indicated that a combination of high group pressure and low group safety objectives as core conditions, with high group contagion, high group psychological safety, and low group safety culture as marginal conditions, was sufficient to form high unsafe behavior in mining communities. Configuration 3b indicated that a combination of high group pressure and low group safety objectives as core conditions, with high group cohesion, high group contagion, and high group psychological safety as marginal conditions, was sufficient to form high unsafe behavior in mining communities. Comparing Configuration 3a and 3b, it can be seen that their core conditions were the same, with only the boundary conditions being different. It was evident that the absence of safety goals under high group pressure can lead to high unsafe behavior among miner groups. Shen et al.24 also believed that stress can affect the unsafe behavior of workers.

-

(4)

Scattered type (Configuration 4); Low group cohesion type. Configuration 4 (~ GC1 × GC2 × GP × GPS × GSO × GSC) had a consistency of 0.917 and a unique coverage of 0.036. In this configuration, low group cohesion, high group contagion, and high group psychological safety collectively played core roles, while high group pressure, high group safety objectives, and high group safety culture played supporting roles. Zhou et al.13 pointed out that group factors had a more significant impact on the unsafe behavior of miners.

Configuration analysis of non-high unsafe behavior in miner groups

The analysis presented in Table 6 revealed three pathways influencing non-high unsafe behaviors among the miner group: Configuration 5, Configuration 6a, and Configuration 6b. Configuration 5 had a consistency of 0.919, Configuration 6a had a consistency of 0.890, and Configuration 6b had a consistency of 0.887. All of these values exceeded 0.800, with the overall consistency for non-high unsafe behaviors among miners being 0.877. This indicated that all three pathways were sufficient conditions for forming non-high unsafe behaviors within the miner group. The complementary combination of six antecedent conditions helped to avoid high unsafe behaviors among miners. Based on the core conditions related to non-high unsafe behaviors, these three influences were named as follows: “Unity and cooperation type” for Configuration 5, and “Cohesion, goals, and culture-driven type” for Configurations 6a and 6b. To present the analysis results more clearly, a configuration path diagram was used to visually display the three paths of non-high unsafe behaviors among the miner group, as shown in Fig. 3.

-

(1)

Unity and cooperation type (Configuration 5), which refers to high group cohesion type. Configuration 5 indicated that the combination of high group cohesion, low group pressure, low group psychological safety as core conditions, low group contagion, and low group safety culture as marginal conditions can effectively lead to non-high unsafe behavior in mining communities. The raw coverage of this configuration was 0.219, with a unique coverage of 0.050. It was evident that high group cohesion contributed to reducing unsafe behavior in mining communities. Leve. et al.20 and Farh. et al.21 both confirmed this viewpoint.

-

(2)

Cohesion, goals, and culture-driven type (Configurations 6a and 6b). Configuration 6a had a consistency of 0.890 and a unique coverage of 0.045. In this configuration, high group cohesion, high group safety goals, and high group safety culture played core roles, while high group contagion played a supportive role, and group pressure was irrelevant. Configuration 6b (GC1 × ~ GP × GPS × GSO × GSC) had a consistency of 0.887, with a unique coverage of 0.208. The presence of high group cohesion, low group pressure, high group safety objectives, and high group safety culture collectively played core roles, with high group psychological safety playing a supportive role, and group contagion being irrelevant. Similarly, by comparing Configuration 2a and 2b, it was evident that the core conditions were the same, with only the marginal conditions differing, indicating that a coordinated configuration of group cohesion, group safety objectives, and group safety culture can inhibit high unsafe behavior in mining communities. It has been shown that enhancing group safety objectives and safety culture significantly improved workplace accidents in coal mining companies, which can bring both internal benefits, such as improving the group’s organizational environment, and external benefits, such as maintaining or improving the company’s reputation48,49. The studies mentioned above further support the findings of this article.

Intervention strategies

In any initial state of a group, if the group is disturbed by multiple external environmental factors and no control strategy is adopted, the level of group safety behavior will deteriorate. Additionally, when the level of group safety behavior decreases, targeted control strategies should be implemented17. Based on the previous analysis, it can be concluded that the key predictive factors leading to high unsafe behavior among miners were group pressure, group safety objectives, and group safety culture. Therefore, the high unsafe behavior of miners can be reduced by reducing group pressure, increasing group safety objectives, and enhancing group safety culture.

-

(1)

Reduce group pressure. Leverage the positive influence of group dynamics to create a relaxed and pleasant team work atmosphere, optimize internal interpersonal relationships, avoid the emergence of group stress, and reduce the incidence of unsafe incidents.

-

(2)

Establish group safety objectives. Introduce advanced technologies and intelligent information systems to build a smart mine, optimize the coal mining environment, and encourage and support every miner to actively participate in safety decision-making, fully implement the concept of safe production, and promote behaviors that align with the safety standards of coal mining enterprises.

-

(3)

Enhance group safety culture. Establish a group safety incentive mechanism, encourage mutual reminders and supervision among employees during operations, form mutual protection and linkage, strengthen safety awareness education for new employees, and cultivate a good team safety atmosphere.

Conclusions

In this paper, the group dynamics and institutional environmental elements of miners were analyzed. 185 front-line miners in China were studied by integrating the survey design, NCA, and fsQCA methods. It also explored the complex causal relationships between group cohesion, group contagion, group pressure, group psychological safety, group safety objectives, group safety culture, and miners’ group unsafe behavior, and drew predictive conclusions. The main contents can be drawn as follows:

-

(1)

There are six configuration paths for high unsafe behavior of miner groups and three configuration paths for non-high unsafe behavior. The configuration analysis results of high and non-high unsafe behavior are consistent, confirming the asymmetry, synergy, and equivalence between the influencing factors of high and non-high unsafe behavior among miner groups.

-

(2)

Individual group dynamics or institutional environment elements do not constitute necessary conditions for the highly unsafe behavior of miner groups, and only the combined effect of different elements can lead to the occurrence of group unsafe behavior. This further validates the multiple complex causal relationships underlying miner group unsafe behavior, demonstrating the scientific rationality of using a combination of NCA and fsQCA methods to predict miner group unsafe behavior.

-

(3)

Identifying six conditional configurations of high unsafe behavior in miner groups, the configuration path covered by group pressure is the most common among the six configurations. Four configurations exhibit existing variables, while group safety objectives and group safety culture mostly appear as “non” or “optional” redundant variables within the six configurations, indicating that group pressure, group safety objectives, and group safety culture are key elements of miner group safety behavior. Additionally, group safety culture is more predictive of a miner’s unsafe behavior than group safety objectives.

Limitations and future research directions

This study conducted a group analysis and prediction of the complex causal relationships between antecedent variables of group unsafe behavior based on group dynamics and institutional environment elements, but there were still shortcomings, as reflected in the fact that the research on the antecedent conditions of unsafe behavior was mainly based on cross-sectional questionnaires, which may not yet be completely clear for the changes of each element in the process of miners’ operations over time. Therefore, in the future, it is also possible to incorporate the time dimension and use time series data for dynamic analysis to achieve the dynamic QCA process of inhibiting unsafe behavior of miner groups.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xie, X. et al. Risk prediction and factors risk analysis based on IFOA-GRNN and apriori algorithms: Application of artificial intelligence in accident prevention. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 122, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2018.11.019 (2019).

Brodny, J. & Tutak, M. The comparative assessment of sustainable energy security in the Visegrad countries. A 10-year perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 317, 128427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128427 (2021).

Fa, Z., Li, X., Qiu, Z., Liu, Q. & Zhai, Z. From correlation to causality: Path analysis of accident-causing factors in coal mines from the perspective of human, machinery, environment and management. Resour. Policy 73, 102157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102157 (2021).

Mishra, S. A. D. P. Effects of particle size, dust concentration and dust-dispersion-air pressure on rock dust inertant requirement for coal dust explosion suppression in underground coal mines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 126, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.03.030 (2019).

Liu, Y., Liang, Y. & Li, Q. Cause analysis of coal mine gas accidents in China based on association rules. Appl. Sci. 13(16), 9266. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13169266 (2023).

Li, L., Guo, H., Cheng, L., Li, S. & Lin, H. Research on causes of coal mine gas explosion accidents based on association rule. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 80, 104879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2022.104879 (2022).

You, M., Li, S., Li, D. & Xia, Q. Study on the influencing factors of miners’ unsafe behavior propagation. Front. Psychol. 10, 2467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02467 (2019).

Xiangmei, W., Xiaoxiao, G. & Wang, Y. Research on the network topology characteristics of unsafe behavior propagation in coal mine group from the perspective of human factors. Resour. Policy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104020 (2023).

Cartwright, D. Achieving change in people: Some applications of group dynamics theory. Human Relat. 4(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675100400404 (1951).

Yuxin, W. et al. Modelling and analysis of unsafe acts in coal mine gas explosion accidents based on network theory. Process Safety Environ. Prot. 170, 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.11.086 (2023).

Ma, H., Zhiguo, W. & Chang, P. Social impacts on hazard perception of construction workers: A system dynamics model analysis. Saf. Sci. 138, 105240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105240 (2021).

Xie, X. & Wang, H. How can open innovation ecosystem modes push product innovation forward? An fsQCA analysis. J. Bus. Res. 108, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.011 (2020).

Yu, K., Cao, Q., Xie, C., Qu, N. & Zhou, L. Analysis of intervention strategies for coal miners’ unsafe behaviors based on analytic network process and system dynamics. Saf. Sci. 118, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.05.002 (2019).

Neal, A., Griffin, M. A. & Hart, P. M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 34(1–3), 99–109 (2000).

Kapp, E. A. The influence of supervisor leadership practices and perceived group safety climate on employee safety performance. Saf. Sci. 50, 1119–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.11.011 (2012).

You, Q. et al. Research on risk analysis and prevention policy of coal mine workers’ group behavior based on evolutionary game. Resour. Policy 80, 103262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.103262 (2023).

Cao, Q., Yu, K., Zhou, L., Wang, L. & Li, C. In-depth research on qualitative simulation of coal miners’ group safety behaviors. Saf. Sci. 113, 210–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.11.012 (2019).

Deng, S., Zhu, H., Cai, Y. & Pan, Y. Group cognitive characteristics of construction Workers’ unsafe behaviors from personalized management. Saf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106492 (2024).

Wang, L., Cao, Q., Han, C., Song, J. & Qu, N. Group dynamics analysis and the correction of coal miners’ unsafe behaviors. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 76(4), 188–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2020.1795610 (2021).

Turner, M. E., Pratkanis, A. R., Probasco, P. & Leve, C. Threat, cohesion, and group effectiveness: Testing a social identity maintenance perspective on groupthink. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 63(5), 781 (1992).

Lee, C. & Farh, J. L. Joint effects of group efficacy and gender diversity on group cohesion and performance. Appl. Psychol. 53(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00164.x (2004).

Fu, L., Song, W., Lv, W. & Lo, S. Simulation of emotional contagion using modified SIR model: A cellular automaton approach. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 405, 380–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2014.03.043 (2014).

Quan Shao, H. W., Zhu, P. & Dong, M. Group emotional contagion and simulation in large-scale flight delays based on the two-layer network model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2021.125941 (2021).

Liang, Q., Zhou, Z., Ye, G. & Shen, L. Unveiling the mechanism of construction workers’ unsafe behaviors from an occupational stress perspective: A qualitative and quantitative examination of a stress–cognition–safety model. Saf. Sci. 145, 105486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105486 (2022).

Yu, M., Qin, W. & Li, J. The influence of psychosocial safety climate on miners’ safety behavior: A cross-level research. Saf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105719 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Root causes of coal mine accidents: Characteristics of safety culture deficiencies based on accident statistics. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 136, 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2020.01.024 (2020).

Mishra, P. C., Panigrahi, R. R. & Shrivastava, A. K. Geo-environmental factors’ influence on mining operation: An indirect effect of managerial factors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26(6), 14639–14663 (2024).

Hui, L. & Chen, H. Does a people-oriented safety culture strengthen miners’ rule-following behavior? The role of mine supplies-miners’ needs congruence. Saf. Sci. 76, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.02.018 (2015).

Zohar, D. A group-level model of safety climate: Testing the effect of group climate on microaccidents in manufacturing jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 85, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.587 (2000).

Kapusta, M., Bąk, P. & Sukiennik, M. Model of the formation of work safety culture in polish mining enterprises. Arch. Min. Sci. https://doi.org/10.24425/ams.2024.150344 (2024).

Li, D., Li, S. & You, M. Research on mine safety situation prediction model: the case of gas risk. https://doi.org/10.1109/WCSP.2019.8927926 (2019).

Rau, P. L. P., Liao, P. C., Guo, Z., Zheng, J. & Jing, B. Personality factors and safety attitudes predict safety behaviour and accidents in elevator workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 26, 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1493259 (2018).

Masia, U. & Pienaar, J. Unravelling safety compliance in the mining industry: examining the role of work stress, job insecurity, satisfaction and commitment as antecedents. SA J. Ind. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i1.937 (2011).

Fu, Y., Ye, G., Tang, X. & Liu, Q. Theoretical framework for informal groups of construction workers: a grounded theory study. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236769 (2019).

Bronkhorst, B., Tummers, L. & Steijn, B. Improving safety climate and behavior through a multifaceted intervention: Results from a field experiment. Saf. Sci. 103, 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.009 (2018).

Zaccaro, S. J. & Lowe, C. A. Cohesiveness and performance on an additive task: Evidence for multidimensionality. J. Soc. Psychol. 128(4), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1988.9713774 (1988).

Dul, J. Identifying single necessary conditions with NCA and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1516–1523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.134 (2016).

Ragin, H. L. S. C. The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies (Univ of California Press, 2014). https://doi.org/10.2307/1972971.

Lee, C. K. H. How guest-host interactions affect consumer experiences in the sharing economy: New evidence from a configurational analysis based on consumer reviews. Decis. Support Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2021.113634 (2022).

Olya, H., Taheri, B., Farmaki, A. & Joseph Gannon, M. Modelling perceived service quality and turnover intentions in gender-segregated environments. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 46(1), 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12664 (2022).

Miao, Z. & Guohao, Z. Configurational paths to the green transformation of Chinese manufacturing enterprises: a TOE framework based on the fsQCA and NCA approaches. Sci. Rep. 13, 19181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46454-9 (2023).

Moreno, F. C., Prado-Gascó, V., Hervás, J. C., Núñez-Pomar, J. & Sanz, V. A. Predicting future intentions of basketball spectators using SEM and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 69(4), 1396–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.114 (2016).

Yuan, B., Shuitai, X., Chen, L. & Niu, M. How do psychological cognition and institutional environment affect the unsafe behavior of construction workers?—Research on fsQCA method. Front. Psychol. 13, 875348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875348 (2022).

Du, Y., Liu, Q., Kim, P. H. & Li, J. Riding the waves of change: Using qualitative comparative analysis to analyze complex growth patterns in entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587241249330 (2024).

Fiss, P. C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 54(2), 393–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.60263120 (2011).

Judge, W. Q., Stav Fainshmidt, J. & Brown, L. Institutional systems for equitable wealth creation: Replication and an update of Judge et al. (2014). Manag. Org. Rev. 16(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2020.1 (2020).

Hongxia, L., Yongbin, F., Shuicheng, T., Fen, L. & Huan, Li. Study on the job stress of miners. Proc. Eng. 84, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.10.431 (2014).

Vassem, A. S., Fortunato, G., Bastos, S. A. P. & Balassiano, M. Fatores constituintes da cultura de segurança: olhar sobre a indústria de mineração. Gestão & Produção 24, 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-530x1960-16 (2017).

Opoku, F. K., Kosi, I. & Degraft-Arthur, D. Enhancing workplace safety culture in the mining industry in Ghana. Ghana J. Dev. Stud. 17, 23–48. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v17i2.2 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1904210, Grant No. 51874237), and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 20XGL025)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.W. conceived the study, designed the study, collected the data, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. S.T. and H.L. guided the writing process and provided a lot of help in language editing. L.C. provided writing ideas and methods. Y.K. collected the data. J.M. analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, S., Wang, R., Li, H. et al. Predictive analysis of miners’ group unsafe behavior based on group dynamics and institutional environment. Sci Rep 15, 9263 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89860-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89860-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A simulation study on risk emergence mechanism and transmission path of coal mine workers’ unsafe behaviours based on DEMATEL-ISM and Arena simulation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Integrated multimethod analysis of miners’ safety behavior and risk interaction for practical applications

Scientific Reports (2025)