Abstract

The detection of wind turbine blades (WTBs) damage is crucial for improving power generation efficiency and extending the lifespan of turbines. However, traditional detection methods often suffer from false positives and missed detections, and they do not adequately account for complex weather conditions such as fog and snow. Therefore, this study proposes a WTBs damage detection model based on an improved YOLOv8, named AUD-YOLO. Firstly, the ADown module is integrated into the YOLOv8 backbone to replace some conventional convolutional down-sampling operations, decreasing the parameter count while boosting the model’s capability to extract image features. Secondly, the model incorporates the UniRepLKNet large convolution kernel with the C2f module, enabling it to learn complex image features more comprehensively. Thirdly, a lightweight DySample dynamic up-sampler substitutes the nearest-neighbor interpolation up-sampling method in the original model, thereby obtaining richer semantic information. Experimental results show that the AUD-YOLO model demonstrates outstanding performance in detecting WTBs damage under complex and adverse weather conditions, achieving a 3% improvement in the mAP@0.5 metric and a 6.2% improvement in the mAP@0.5–0.95 metric compared to YOLOv8. Moreover, the model has only 2.5M parameters and 7.2 GFLOPs of computational complexity, this adaptation renders it appropriate for implementation in environments with constrained computational capacity, where precise detection is critical. Lastly, a mobile application named WTBs Damage Detection system is designed and developed, enabling mobile-based detection of WTBs damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the ongoing rise in global energy demand and the heightened focus on renewable energy, wind power, as a clean and renewable energy source, has received widespread attention1. According to the Global Wind Energy Report 2023, China’s wind power installed capacity is expected to reach 700 to 800 gigawatts by 2030, continuing to lead the global wind energy market2. With the rapid growth in demand for wind energy, WTBs with higher productivity and greater stability in power generation have become essential. WTBs blades are critical components in wind power systems for capturing wind energy, and they are also the most vulnerable parts, accounting for approximately 15%-20% of the total cost of WTBs3. Their performance directly affects the overall efficiency and reliability of the power generation system. However, during operation, WTBs blades are often affected by external factors such as adverse weather and mechanical wear, which can lead to various forms of damage, including delamination and cracks4,5. This damage not only reduces the performance of the blades but can also cause equipment failures or even accidents, posing serious safety risks and economic losses to the wind power system. Therefore, timely detection and maintenance of WTBs blade damage are crucial for ensuring the safety and economic viability of wind power systems. Therefore, adopting efficient methods to detect and promptly repair surface defects in WTBs is a crucial strategy for reducing maintenance costs and extending the lifespan of turbines.

Many researchers have explored more efficient and safer methods for detecting WTBs damage6,7,8. Existing research on WTBs damage detection can be roughly divided into physics-based methods and data-driven methods9,10. Physics-based detection techniques mainly encompass vibration analysis11, acoustic emission(AE)12, ultrasound13, and thermography14. Liu et al.15 utilized vibration signal analysis based on the empirical wavelet threshold method to diagnose the damage type of blade bearings. Ghoshal et al.16 tested four vibration-based techniques for detecting partial blade damage. These methods assess the blades’ vibrational behavior when stimulated, using patches of piezoelectric ceramic actuators attached to the blades. Using vibration-based techniques for detecting blade damage poses a significant challenge: distinguishing vibrations caused by damage from those due to environmental and operational factors. Xu et al.17 employed acoustic emission technology for health monitoring of a 59.5 m long composite WTBs blade under fatigue loads, identifying and classifying various damages on the WTBs blade. Tang et al.18 demAonstrated the feasibility of AE technology for real-time monitoring of WTBs blades’ structural health. They conducted cyclic loading using a compact resonant mass to accurately simulate operational conditions. A primary challenge of this technology is distinguishing acoustic emission signals caused by damage from those due to noise, which complicates and significantly increases the cost of data processing. Yang et al.19 compared nonlinear acoustics and guided wave techniques, finding that the former is less sensitive to WTBs faults, while the guided wave method can detect and locate faults using a novelty detector network approach. Oliveira et al.20 proposed integrating a novel detection technique with non-destructive ultrasonic examination to precisely locate structural defects in WTBs. Ultrasonic inspection technology typically faces a limitation in that it requires direct placement of ultrasonic transducers on the surface or inside the blade. This may necessitate shutdowns and physical contact with the blade, resulting in production interruptions and additional maintenance costs. Hwang et al.21 proposed a continuous line laser scanning thermography system, which remotely detects delamination and surface damage inside WTBs by analyzing the propagation patterns of laser-induced thermal waves. Sanati et al.22 utilized active and passive thermography techniques for condition monitoring of WTBs blades. Thermographic techniques rely on detecting temperature differences on the surface of the target. However, early-stage damage often does not cause significant temperature changes, making thermography less suitable for detecting early-stage damage. Although these traditional blade damage detection methods can effectively identify WTBs blade damage under specific conditions, their application is somewhat limited by environmental factors and operational requirements.Traditional WTBs damage detection techniques each have their limitations. For instance, vibration analysis is susceptible to environmental noise and operational vibrations, acoustic emission is prone to noise interference and false alarms, ultrasonic testing requires direct contact with the blade surface or interior, potentially causing production interruptions and additional maintenance costs, and thermography demands high geometric and physical surface property standards, with limited capability in detecting early-stage damage. These constraints collectively impact the applicability and accuracy of traditional methods in complex environmental conditions and early damage detection scenarios.

Data-driven object detection methods have made significant progress in the field of WTBs damage detection, primarily consisting of machine learning and deep learning approaches. Machine learning methods analyze and model various sensor data from WTBs, enabling effective identification, prediction, and localization of potential damages. In machine learning methods, traditional feature engineering and algorithmic models are widely applied for damage detection in WTBs. Chandrasekhar et al.23 proposed an innovative machine learning-based method for damage detection in operational WTBs. This method uses a Gaussian process regression model to monitor the frequency changes of the blade and, by combining the blade frequency response data, can identify potential damages by detecting abnormal deviations. Regan et al.24 proposed a damage detection method based on supervised machine learning algorithms, utilizing logistic regression (LR) and support vector machine (SVM) to process and classify acoustic signals for health status. Experimental results show that this method can effectively identify blade damages, providing an efficient and feasible solution for defect detection in wind turbines. Dhanraj et al.25 proposed a machine learning-based method for crack detection and localization in WTBs, using multi-layer perceptrons (MLP) and logic model trees (LMT) as data modeling techniques. The MLP classifier achieved a detection accuracy of 94.75%, demonstrating its potential for monitoring wind turbine blade conditions. Deep learning-based methods for WTBs damage detection utilize efficient neural network models to automatically and accurately identify blade damage from images, unaffected by environmental constraints and with lower safety risks26. Deep learning-based object detection models can be divided into two-stage and one-stage detection methods. Representative two-stage models include Faster R-CNN27 and Mask R-CNN28, which use a candidate box extraction method to first extract candidate regions and then perform classification. On the other hand, one-stage methods directly use fixed anchor boxes for classification, with representative models including SSD29 and the YOLO series. While two-stage detection methods achieve higher detection accuracy, the generation of candidate regions incurs greater computational costs, reducing real-time performance in practical applications. One-stage detection methods, however, offer higher detection efficiency and better real-time performance, making them more widely used. Among these, the YOLO series, in particular, has achieved notable research results in WTBs damage detection. Zhang et al.30 proposed a surface fault diagnosis model for WTBs based on YOLOv5, called SOD-YOLO. This model adds a smaller feature fusion layer and a convolutional block attention module to YOLOv5, thereby reducing the loss of features of small target defects. However, this algorithm does not consider the detection performance of damage under complex weather conditions such as cloudy or foggy weather. This limitation may affect the reliability and applicability of the algorithm in real-world scenarios. Ran et al.31 proposed an AFB-YOLO algorithm, based on YOLOv5s with attention and feature balance. The improved model can detect low-resolution and unclear damage features of WTBs, significantly enhancing the detection capability for small target defects. However, the datasets cited in the literature primarily focus on single types of damage, lacking image data from various environments and conditions such as different lighting conditions and weather conditions. This limitation may result in poorer detection performance of the algorithm in practical scenarios for WTBs damage detection. Liu et al.32 , inspired by the design concept of YOLOX, proposed a lightweight feature fusion network for detecting surface defects of WTBs, incorporating an attention mechanism. This significantly improved detection accuracy while maintaining good real-time performance. However, this study lacks comparative analysis with mainstream algorithms and focuses on a relatively narrow range of detection scenarios. As a result, its generalizability in real-world detection scenarios may be limited. Hu et al.33 made improvements based on the yolov7-Tiny algorithm. The improved model demonstrated higher detection accuracy, particularly excelling in detecting small-sized damages on the blades. However, the dataset used in this study is relatively small and may not comprehensively represent the diversity of surface defects on WTBs. This limitation could impact the algorithm’s robustness and generalization in practical applications. Liu et al.34 considering the characteristics of the WTBs damage dataset, proposed a damage detection algorithm for WTBs based on YOLOv8, which boasts precise detection capabilities and minimal computational demands. However, the study did not consider the need for real-time detection, nor did it cover the various types of damage that WTBs may encounter in different environments, climates, and geographical locations. This could affect the algorithm’s generalization ability and practical application effects.

Up to now, significant progress has been made in WTBs damage detection based on the YOLO algorithm in simple environments35,36. However, its application in complex weather conditions such as cloudy, foggy, and snowy weather has not been fully considered. Therefore, firstly, drones equipped with high-resolution cameras is used to extensively collect images of WTBs damage in various environments. Through data preprocessing, scenarios such as cloudy, foggy, and snowy weather conditions were simulated to verify the algorithm in more realistic environments. Secondly, an AUD-YOLO model is established, to tackle the challenges related to the high computational demands and diminished detection accuracy of damage detection models under complex weather conditions. The primary contributions of this research are outlined as follows:

-

(1)

To reduce parameters and capture image features more efficiency, the ADown module is integrated into the backbone of YOLOv8.

-

(2)

To obtain a larger reception field without relying on deep stacking, a large kernel CNN architecture named UniRepLKNet with the C2f module is used in the neck part.

-

(3)

To reduce computationalresoures and adapt to the time-intensive scenario, the DySample mechanism is introduced.

-

(4)

An independently developed software named WTBs Damage Detection system is designed and implemented for damage detection on mobile devices.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: Section “YOLOv8” provides a detailed introduction to the principles of the YOLOv8 algorithm. Section “AUD-YOLO” outlines the improved method adopted in this study. Section “Experiment” presents the experimental details, including dataset preparation, parameter settings, and evaluation metrics. Section “Results and analysis” displays the experimental results and their analysis. Section “Android mobile application development elaborates on the deployment of the improved model on Android mobile devices. Finally, Section “Conclusion” concludes the study and presents the conclusions.

YOLOv8

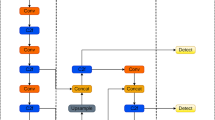

The YOLOv8 algorithm is a single-stage detection model improved by Ultralytics based on the YOLOv5 model. As shown in the Fig. 1, its model structure mainly comprises three parts: the backbone, the neck, and the head.

The backbone is mainly responsible for feature extraction from the image, primarily composed of modules such as Conv, C2f, and SPPF. The Conv module performs convolution, BN, and SiLU operations on the input image. YOLOv8 updates the C3 module from YOLOv5 to the more advanced cross-scale feature fusion (C2f) module, enhancing feature fusion capability while ensuring a lightweight structure and allowing richer gradient flow information through the network. The SPPF module’s function is to convert feature maps of different dimensions into uniform-sized feature tensors.

The neck component facilitates the fusion of multi-scale features, and its structure is PANet. The PANet37,38 structure includes a feature pyramid (FPN) and a path aggregation network (PAN). The combination of these two structures fully realizes the fusion of upward and downward feature information flow. Through up-sampling and channel concatenation, three output branches are passed to the head structure.

The head part is used to obtain the category and location information of the target objects based on feature maps of different sizes. It utilizes a decoupled head architecture, distinguishing between classification and detection to mitigate conflicts between these tasks39. Moreover, in contrast to conventional techniques that employ Anchor-Based predictions to determine the dimensions and location of anchor boxes, the Anchor-Free method is now used to directly predict the center points and aspect ratios of the targets. This reduces the number of Anchor boxes, thereby improving the detection speed of the model.

AUD-YOLO

The YOLOv8 model, renowned for its rapid detection capabilities and precise accuracy, is extensively utilized across various object detection applications. However, it is prone to missed detections and false positives when detecting WTBs damage in complex scenarios. Additionally, applying the algorithm to practical detection tasks results in high computational costs, making it difficult to embed into resource-limited mobile devices, thereby restricting its practical application capabilities. To address these issues, this study selects YOLOv8n as the base research model and proposes a new WTBs damage detection model, AUD-YOLO, by improving and redesigning its network structure considering model parameters and computational cost.

First, the ADown module is integrated into the backbone of YOLOv8, replacing some traditional Conv down-sampling operations, helping the model better understand the global structure and semantic content of the image. Second, the C2f-UniRepLKNet module is introduced into the YOLOv8n network, enhancing the feature extraction capability for WTBs damage and allowing more accurate fitting of damage targets in different directions and sizes. Finally, the DySample dynamic upsampling method is proposed to supplant the conventional nearest-neighbor up-sampling, this approach minimizes the degradation of image feature information throughout the upsampling process, and improving the network’s ability to perceive detailed features. The overall network structure of AUD-YOLO is shown in Fig. 2.

ADown

Cracks and detachments on WTBs typically manifest as subtle, localized features that are critical for damage detection. In deep learning models, downsampling is a key operation that reduces feature map size to improve computational efficiency and expand the receptive field. However, traditional downsampling methods often lead to the loss of fine-grained details, negatively impacting detection accuracy. To address this issue, this study introduces the ADown downsampling module from YOLOv940, replacing conventional downsampling operations.

The ADown module employs an adaptive mechanism to dynamically determine feature transmission paths based on the variability of information across different regions of the input feature map. This flexible downsampling strategy ensures the preservation of critical small-scale features such as cracks and detachments, thereby improving detection accuracy. Additionally, the ADown module incorporates a multi-scale feature fusion strategy to integrate features at different scales. This capability allows the model to handle both small cracks and large detachment regions, effectively mitigating the detail loss associated with excessive downsampling and significantly enhancing target detection performance.

Another major challenge in WTBs damage detection is the presence of complex environments, such as clouds, ground, and sky, which can interfere with the detection task. To address this, the ADown module extracts global contextual information using average pooling, enhancing the model’s understanding of complex backgrounds and reducing their impact on detection results. Simultaneously, the lightweight design of the module, featuring depthwise separable convolutions, significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational complexity. This efficient design makes the module particularly suitable for real-world applications involving resource-constrained platforms like drones or edge devices. Therefore, this study integrates the ADown module into the backbone network of YOLOv8, replacing several conventional convolutional downsampling operations to enhance the model’s ability to capture image features. The structure of the ADown module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Specifically, the implementation of the ADown module includes the following steps: First, the input feature map undergoes average pooling to reduce dimensionality, extract global information, and provide broader contextual support. Next, the feature map is split into two parts: the first part directly passes through a convolution layer to retain detailed features, while the second part undergoes max pooling followed by a convolution layer to capture prominent features. Finally, the processed feature maps from both parts are concatenated along the channel dimension to produce the final output feature map. The ADown module design comprehensively addresses the dual requirements of feature extraction and downsampling. It not only excels in preserving critical information but also significantly enhances overall model performance through an efficient downsampling strategy, demonstrating exceptional applicability and reliability in WTBs damage detection tasks.

UniRepLKNet large kernel convolution

Large-kernel Convolutional Neural Networks (ConvNets) have proven highly effective at detecting less dense patterns and generating superior features, yet significant opportunities still exist for advancements in their structural design. Although the Transformer architecture has shown broad adaptability in various fields, it faces challenges concerning processing speed, memory usage, clarity, and fine-tuning. In response to these challenges, Tencent and the Chinese University of Hong Kong have jointly developed a new model architecture, UniRepLKNet, which leverages large-kernel ConvNets41. The architectural layout of UniRepLKNet is illustrated in Fig. 4.

The unique advantage of large-kernel convolution lies in its ability to achieve a large receptive field without relying on deep stacking, thereby avoiding the problem of diminishing returns from increasing depth. UniRepLKNet decouples receptive fields, feature abstraction, and model depth, and flexibly utilizes the advantages of large convolution kernels to build an efficient and powerful large-kernel ConvNet architecture. This study integrates UniRepLKNet with the C2f module in the neck part, allowing the network to learn complex features of images more comprehensively.

The structural design of UniRepLKNet follows four guiding principles. The first is structural re-parameterization. As shown in the figure, the module that incorporates the Dilated Reparam Block is named the Large Kernel Block (LarKBlock), while the module using the 3x3 Depthwise Convolution (DWconv) is designated as the Small Kernel Block (SmaKBlock). The foundation of the Dilated Reparam Block lies in equivalent transformation, enhancing feature extraction by combining non-dilated large kernel convolution layers (kernel size K=9) and multiple dilated small kernel convolution layers (kernel sizes k=5, 3, 3, 3). The dilation rate r influences the arrangement of non-zero elements in the convolution kernel; a higher dilation rate means more zero elements within the kernel, which helps maintain performance while reducing computational complexity. For example, to handle bigger input dimensions, as the large kernel K expands to 13, the sizes and dilation rates of the small kernels are adjusted accordingly to k = (5, 7, 3, 3, 3) and r = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). This modification can emulate a large convolution layer with equivalent kernel sizes of (5, 13, 7, 9, 11). By adopting the concept of structural re-parameterization, spatially sparse features can be captured more effectively, thus improving the model’s capacity to discern complex patterns.

Furthermore, the architectural design incorporates Large Kernel Blocks predominantly within the model’s intermediate and upper layers, utilizing efficient mechanisms like the SE Block to enhance depth. The SE Block consolidates the feature map’s channels into a single vector through a comprehensive compression process, thereby encapsulating the comprehensive contextual details of the features. This vector undergoes activation using a densely connected layer coupled with a sigmoid function, which reinstates the original channel count to align with the input features. Subsequently, this activated vector is applied in an element-wise fashion to the initial feature map, either amplifying or attenuating specific channels within the map. Through the SE Block, the model adeptly learns and depicts intricate features of the input data while ensuring computational efficiency.

Thirdly, the design of convolution kernel sizes should be based on the downstream tasks and the specific framework employed, selecting appropriate kernel sizes to further enhance feature extraction. Finally, regarding the scaling of the model, for small models that already use many large kernels, depthwise separable 3\(\times\)3 convolution blocks should be considered when increasing model depth. Although additional large kernels are not added, since the receptive field is already sufficiently large, using efficient 3\(\times\)3 convolution operations can still elevate the abstraction level of features. This strategy maintains computational efficiency while ensuring a higher-level understanding and representation of input data by the model.

In summary, UniRepLKNet achieves significant improvements in capturing sparse patterns and generating high-quality features through innovative structural design and optimization strategies, providing new insights for building efficient and powerful convolutional neural networks.

DySample

In tasks related to object detection, upsampling is a common operation used to increase the size and resolution of feature maps. Traditional upsampling methods, such as nearest neighbor interpolation and bilinear interpolation, typically consider only simple contrasts or linear combinations between pixels, which could lead to the omission of essential image details. In recent years, kernel-based dynamic upsamplers (such as CARAFE42) have shown significant performance improvements. However, these methods rely on time-consuming dynamic convolutions and additional sub-networks to generate dynamic kernels, leading to substantial computational and parameter overhead, which is not ideal for designing lightweight network architectures.

To address this issue, this research proposes using the lightweight DySample dynamic upsampler to replace the nearest neighbor interpolation method in the original YOLOv8 model, thereby obtaining richer semantic information43. DySample employs a point-based sampling approach and an adaptable sampling perspective for upsampling, entirely eliminating the need for time-intensive dynamic convolution operations and supplementary sub-networks. This mechanism demands fewer computational resources, enhances image resolution without imposing additional load, and improves the operational effectiveness and capabilities of the model while conserving computational resources. The Fig. 5 depicts the dynamic upsampling process in DySample, highlighting the design of the sampling point generator.

In this context, Figure (a) illustrates the DySample upsampling process. First, the original feature map X creates a sampling set S through the sampling point generator. Then, the gridsample function is used to resample the input features, ultimately obtaining the upsampled feature \(X'\). The sampling set is used to determine the grid positions, and this process can be defined as follows.

Figure (b) depicts the sampling point generator in DySample. The sampling set S generated by the sampling generator includes the original sampling grid G and the generated offset O. The offset O is created using a method combining linear transformation and pixel shuffling, and its range can be influenced by both static and dynamic factors. For instance, using the static factor sampling method, consider a feature map with dimensions \(C \times H \times W\) and an upsampling factor s. The feature map is initially processed through a linear layer, which has an input channel of C and an output channel of \(2{s}^{2}\), generating an offset O of size \(2{s}^{2}HW\). This is then reshaped into the shape of \(2\times sH\times sW\) through pixel shuffling. Finally, the offset O is combined with the original grid positions G to derive the sampling set S. For the dynamic factor sampling method, beyond the linear layer and pixel shuffling, a dynamic range factor is introduced. Initially, a range factor is produced, which is then utilized to modify the offset O. In the figure, \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid function.

Overall, DySample achieves efficient dynamic upsampling through the aforementioned steps, preserving more image detail while significantly reducing computational overhead. Through this design, DySample not only improves the quality of upsampling but also enhances the resolution and semantic information of the feature maps, making it excel in various computer vision tasks.

Experiment

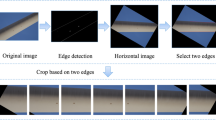

Data collection and preparation

The dataset was collected using a high-resolution drone, specifically the DJI Mavic 2 Pro, equipped with the Hasselblad L1D-20c camera. This camera features a 20-megapixel 1-inch CMOS sensor, which allows for the precise capture of intricate details and rich color information, ensuring high image quality. The image samples were sourced from two wind farms in Liaoning and Jiangsu provinces, China. A total of 600 original damage images were collected, encompassing two main types of damage: cracks and peeling. Among these, 287 images depict cracks, and 313 images depict peeling. All images were annotated individually using the Labelme package, ensuring the accuracy of the data. To enhance the diversity of the data and effectively train deep learning models, several data augmentation techniques were applied to the original images. These included image flipping, rotation, and HSV color space adjustments. Additionally, to better simulate real-world complex environmental conditions, the imgaug library was used to introduce variations such as cloudy, foggy, and snowy conditions, further enhancing the model’s robustness. Through these preprocessing operations, the dataset was expanded to 4,400 images. To prevent overfitting, the dataset was split into training and validation sets in a 9:1 ratio.

Experimental Environment and Parameter Configuration

In this experiment, training was conducted using a GPU equipped with an RTX 3080 graphics card and an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8255C CPU. The operating system used was Ubuntu 20.04, with a programming environment based on Python 3.8. The deep learning framework utilized was PyTorch 2.0.0, and the CUDA version was 11.8. The training parameters are detailed in the Table 1.

Valuation metrics

To objectively evaluate the performance of the algorithm in detecting blade damage under complex environments, this experiment uses the following metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), Average Precision (AP), Mean Average Precision (mAP), number of parameters (Params) and Giga Floating Operations Per Second (GFLOPs).

In the above formulas, TP indicates the count of samples correctly classified as positive by the model, FP indicates the count of negative samples that are mistakenly predicted as positive, and FN indicates the count of positive samples that are incorrectly identified as negative. Precision (P) is defined as the proportion of true positive samples relative to the total number of samples that the model identifies as positive. Recall (R) is the proportion of true positive samples correctly identified out of all actual positive samples. AP reflects the accuracy of a single category and is evaluated through the computation of the area beneath the precision-recall curve. A higher AP indicates better model performance across different thresholds. Mean Average Precision (mAP) is the average of AP across all categories, measuring the model’s overall performance across different categories. mAP@0.5 is the average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 for all categories, mAP@0.5:0.95 represents the mean precision computed across all IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95, with a step size of 0.05. In experiments, a higher mAP value indicates better model performance in detecting WTBs damage.

The parameters(params) count in a model signifies the aggregate number of trainable parameters it contains. Meanwhile, the computational cost, expressed in GFLOPs, indicates the volume of floating-point calculations executed by the model every second. Models with fewer parameters and reduced computational demands are considered more efficient and lightweight.

Results and analysis

Ablation experiment

To validate the improvement effect of the proposed modules on the model, ablation experiments were conducted on a self-made WTBs damage dataset. Using YOLOv8n as the baseline model, three improvement methods were proposed. Firstly, the ADown module was integrated into the backbone of YOLOv8. Secondly, UniRepLKNet was fused with the C2f module in the neck part. Finally, the upsampling method was improved to the DySample upsampling method. The improvement modules were cumulatively added one by one, and the results of the related ablation experiments are shown in the Table 2. In the table, “A” stands for ADown downsampling, “U” stands for integrating UniRepLKNet, and “D” stands for Dysample upsampling.

As shown in the Table 2, the improvements made to the YOLOv8n model not only enhance detection accuracy but also achieve model lightweighting. By using the ADown module to replace some traditional Conv downsampling operations in the backbone of YOLOv8, the model can better capture image features and sufficiently extract blade damage information. Compared to the original YOLOv8n model, mAP@0.5 increased by 1.6%, and mAP@0.5–0.95 increased by 2.7%. Additionally, the number of parameters decreased by approximately 0.3M, and computational complexity reduced by 0.5G. Therefore, the ADown module has been proven to be an efficient feature extraction module, improving detection accuracy while also offering advantages in reducing the number of parameters and computational efficiency. After introducing the C2f-UniRepLKNet module into the YOLOv8n network, mAP@0.5 increased by 1.2%, and mAP@0.5–0.95 increased by 0.6%. At the same time, the number of parameters decreased by approximately 0.21M, and computational complexity reduced by 0.4G. This improvement is attributed to the unique advantage of using large kernel convolution, which achieves a large receptive field without deep stacking. This avoids the diminishing returns problem associated with increased depth, allowing the network to more comprehensively learn complex image features. Therefore, this improvement method not only helps to enhance the model’s detection accuracy but also facilitates model deployment on devices.After replacing the original model’s upsampling method with DySample, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5–0.95 improved by 0.8% and 1%, respectively, with almost no change in the number of model parameters. The reason for this improvement is that DySample is a lightweight dynamic upsampler that can enhance image resolution without increasing computational resources, reducing the degradation of image characteristics during upsampling. This enhances the model’s representational capacity and detection performance.

From the table data, it can also be seen that integrating the ADown downsampling and C2f-UniRepLKNet modules resulted in a 2.7% increase in mAP@0.5 and a 4.4% increase in mAP@0.5–0.95, while reducing the number of parameters by 0.49M and the computational complexity by 0.9G, further enhancing detection performance. Ultimately, by integrating all three improvement methods, the precision reached 94.5%, recall reached 87.4%, mAP@0.5 improved from the initial 89% to 92%, and mAP@0.5–0.95 increased from the initial 62.5% to 68.7%.The Fig. 6 below shows the mAP values for each category and the overall mAP value obtained on the WTBs damage validation dataset for the baseline model YOLOv8n and the improved model AUD-YOLO. Figure (a) shows the PR curve of YOLOv8n, and Figure (b) shows the PR curve of AUD-YOLO.

From the figure, it can be seen that AUD-YOLO achieved varying degrees of improvement for each category in the dataset. Specifically, for crack damage, the mAP increased from 93% to 95.7%, and for detachment damage, the mAP increased from 84.9% to 88.2%. This demonstrates the model’s excellent generalization ability.

Comparison experiment

To further validate the accuracy and lightweight nature of the proposed model, it was compared with other mainstream object detection algorithms. The experimental results are shown in the Table 3.

As shown in the Table 3, in the comparative study with YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv7-Tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n and RTDETR models, the proposed AUD-YOLO model achieved the best performance in terms of P, R, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5–0.95. The model’s parameter count is only 2.53M, and the computational complexity is just 7.2G, making it not only highly accurate but also apt for use on edge devices with constrained computing resources. Compared to YOLOv9, AUD-YOLO achieved a comparable detection accuracy of 92%, but it outperformed in terms of the number of parameters and the complexity of computations. Specifically, AUD-YOLO’s parameter count and computational complexity are only 10% and 7% of those of the YOLOv9 algorithm, respectively. This indicates that AUD-YOLO achieves excellent detection accuracy with a smaller parameter count and lower computational complexity, making it more advantageous for deployment in practical applications. Compared to YOLOv11, AUD-YOLO demonstrates superior detection accuracy, achieving a mAP@0.5 of 92%, higher than YOLOv11’s 88.1%. Its precision and recall rates are 0.945% and 0.874%, respectively, outperforming YOLOv11’s 0.922% and 0.814%. Additionally, AUD-YOLO’s mAP@0.5–0.95 is 0.687%, surpassing YOLOv11’s 0.611%. In terms of model lightweighting, AUD-YOLO has 2.53M parameters, slightly fewer than YOLOv11’s 2.59M, with a reduction of about 2%. However, AUD-YOLO’s computational complexity is 7.2 GFLOPs, which is higher than YOLOv11’s 6.3 GFLOPs, reflecting an increase of about 14%. Despite the rise in computational complexity, AUD-YOLO remains within a reasonable range, ensuring efficient operation in practical applications. Overall, the proposed WTBs damage detection model AUD-YOLO demonstrates better detection performance for damage targets in complex scenes, offers a certain advantage in detection speed, and achieves a compromise between accuracy and model lightweighting, rendering it extremely practical. The Fig. 7 illustrates the changes in mAP values among different algorithms during the training process.

The figure clearly demonstrates that both the AUD-YOLO algorithm proposed in this study and the YOLOv9 algorithm exhibit superior performance in terms of mAP. However, given the large number of parameters in the YOLOv9 model, its deployment on edge devices is somewhat limited. In contrast, the AUD-YOLO model, while maintaining high accuracy, reduces the number of parameters and computational demands, making it more suitable for operation on resource-constrained edge devices. In summary, the AUD-YOLO model demonstrates enhanced applicability and usefulness in practical application settings.

Visualization analysis

To visually validate the effectiveness of the improved algorithm on the WTBs damage dataset, a comparative visualization between the original YOLOv8n algorithm (the images in the top row) and the improved algorithm presented in this study (the images in the bottom row) were conducted. Samples were selected from different weather conditions, such as cloudy, snowy, and foggy days, for comparison. The detection results are shown in the Fig. 8.

From the above visual analysis results, it is apparent that, in comparison, the original model has issues with missed detections, inaccurate regressions, and overlapping detection boxes. In contrast, the improved algorithm effectively addresses these problems. As demonstrated in the first detection comparison image, the AUD-YOLO algorithm is notably more effective in identifying targets that were missed by the original model, particularly excelling in the detection of small objects. It can be seen from the second and third detection comparison images that, for targets detected by both models, the improved algorithm significantly enhances the confidence levels on the same target. From the fourth detection comparison image, it is evident that the improved model’s regression accuracy has significantly increased. The enhanced algorithm not only excels in classification but also substantially improves regression accuracy in target localization. More precise localization improves the accuracy of the detection boxes, reducing issues of overlapping and duplicate boxes. In summary, the improved AUD-YOLO algorithm exhibits significant advantages in detection performance, confidence levels, regression accuracy, and adaptability to complex environments, providing a more reliable and efficient solution for small object detection in complex scenes.

Android mobile application development

In this experiment, a mobile application named WTBs Damage Detection was developed to enable WTBs damage detection on mobile devices. This application utilizes the AUD-YOLO model, which is 5.3 MB in size, and deploys the YOLO model onto Android devices using the NCNN framework. NCNN, an open-source high-performance neural network inference framework by Tencent, is optimized for mobile devices. It is designed to meet the deployment and usage needs on mobile platforms, featuring no third-party dependencies and cross-platform compatibility. Additionally, NCNN’s execution speed on mobile CPUs surpasses all currently known open-source frameworks. By using NCNN, deep learning algorithms can be transplanted to mobile devices for efficient execution, thereby enabling the development of AI-powered applications. The deployment process is illustrated in the Fig. 9.

Before deploying the model, it is necessary to export the PyTorch model (.pt file) trained on the server to the ONNX format. ONNX (Open Neural Network Exchange) is an open file format for storing trained models, allowing model files to be shared between different deep learning frameworks and facilitating model migration across frameworks. Next, use the NCNN tool onnx2ncnn to convert the ONNX model to NCNN format, generating .param and .bin files that contain the model’s structure and weight information, suitable for efficient execution on mobile devices. Finally, integrate the NCNN model into the configured Android application and perform inference. By connecting to an actual mobile device, the model can be deployed on the mobile end. The results of using this mobile application for WTBs damage detection in complex environments are shown in the Fig. 10.

In the first image of Fig. 10a, the application detected shedding damage in a snowy environment with an inference time of approximately 11 ms, satisfying the need for instantaneous detection. In the second image of Fig. 10a, the application detected shedding damage in a foggy environment with a detection accuracy of 81.6% and an inference time of approximately 11 ms, also fulfilling the criteria for immediate detection and high-accuracy detection. In the third image of Fig. 10a, the application detected shedding damage in a cloudy environment with detection accuracies of 80.3% and 72.3% and an inference time of approximately 11 ms, again meeting the requirement for real-time and high-precision detection.

In the first image of Fig. 10b, the application detected crack damage in a snowy environment, achieving a detection accuracy rate of 80.1% and an inference time of about 20 ms, satisfying the demand for real-time detection. In the second image of Fig. 10b, the application detected blade damage in a cloudy environment with a detection accuracy of 82.1% and an inference time of about 24 ms, again meeting the requirements for real-time and high-precision detection. In the third image of Fig. 10b, the application detected blade damage in a foggy environment with a detection accuracy of more than 80% and an inference time of about 25 ms, which also fulfills the criteria for instantaneous and highly accurate detection. In summary, the Android mobile application is capable of meeting the needs for real-time and high-precision detection in actual WTBs damage detection.

Conclusion

To enhance the damage detection accuracy of WTBs in complex and harsh weather conditions, a novel AUD-YOLO model is established in this work. Firstly, the ADown module is integrated into the backbone of YOLOv8, replacing some traditional Conv downsampling operations. This significantly reduces the number of parameters while helping the model better capture image features. Secondly, the C2f-UniRepLKNet module is integrated into the YOLOv8n network, strengthening the capability of the algorithm to identify features of WTBs damage, allowing for more precise detection while maintaining the model’s detection efficiency. Thirdly, the DySample dynamic upsampling method is proposed to replace the original nearest neighbor upsampling, significantly reducing the loss of image feature information during upsampling and alleviating the problem of missed detections for small damage targets. Lastly, WTBs Damage Detection system is designed and developed to facilitate damage detection on mobile devices. Experimental results show that compared to the original YOLOv8 model, the proposed AUD-YOLO model demonstrates significant improvements in detection performance metrics. Specifically, the accuracy increased by 2%, the recall rate increased by 2.4%, mAP@0.5 increased by 3%, and mAP@0.5–0.95 increased by 6.2%. These results indicate the superior performance of the AUD-YOLO model in identifying WTBs damage. Additionally, implementation of the WTBs Damage Detection system helps to promote the lightweighting of models and achieve damage detection of WTBs on mobile devices.

The AUD-YOLO model proposed in this study provides a practical and effective solustion for surface damage detection of WTBs. In future research, on one side, we will continue to gather a wider variety of complex damage types to improve the algorithm’s ability to generalize across real-world application contexts. On the other side, we will continue to optimize the algorithm to futher improve its robustness and generalization capability.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dincer, I. Renewable energy and sustainable development: A crucial review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 4, 157–175 (2000).

Global Wind Energy Council. Global wind report 2023. Available online (2023). Accessed on 6 May 2023.

Jureczko, M., Pawlak, M. & Mężyk, A. Optimisation of wind turbine blades. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 167, 463–471 (2005).

McKenna, R., vd Leye, P. O. & Fichtner, W. Key challenges and prospects for large wind turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 53, 1212–1221 (2016).

Kaewniam, P., Cao, M., Alkayem, N. F., Li, D. & Manoach, E. Recent advances in damage detection of wind turbine blades: A state-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 167, 112723 (2022).

Hang, X., Zhu, X., Gao, X., Wang, Y. & Liu, L. Study on crack monitoring method of wind turbine blade based on AI model: Integration of classification, detection, segmentation and fault level evaluation. Renew. Energy 224, 120152 (2024).

Liu, J., Wang, X., Wu, S., Wan, L. & Xie, F. Wind turbine fault detection based on deep residual networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 213, 119102 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. A damage detection system for inner bore of electromagnetic railgun launcher based on deep learning and computer vision. Expert Syst. Appl. 202, 117351 (2022).

de Paula Monteiro, R., Lozada, M. C., Mendieta, D. R. C., Loja, R. V. S. & Bastos Filho, C. J. A. A hybrid prototype selection-based deep learning approach for anomaly detection in industrial machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 204, 117528 (2022).

Du, Y. et al. Damage detection techniques for wind turbine blades: A review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 141, 106445 (2020).

Ou, Y., Chatzi, E. N., Dertimanis, V. K. & Spiridonakos, M. D. Vibration-based experimental damage detection of a small-scale wind turbine blade. Struct. Health Monit. 16, 79–96 (2017).

Kumpati, R., Skarka, W. & Ontipuli, S. K. Current trends in integration of nondestructive testing methods for engineered materials testing. Sensors 21, 6175 (2021).

Yang, B. & Sun, D. Testing, inspecting and monitoring technologies for wind turbine blades: A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 22, 515–526 (2013).

Mori, M., Novak, L. & Sekavčnik, M. Measurements on rotating blades using IR thermography. Experiment. Therm. Fluid Sci. 32, 387–396 (2007).

Liu, Z., Zhang, L. & Carrasco, J. Vibration analysis for large-scale wind turbine blade bearing fault detection with an empirical wavelet thresholding method. Renew. Energy 146, 99–110 (2020).

Ghoshal, A., Sundaresan, M. J., Schulz, M. J. & Pai, P. F. Structural health monitoring techniques for wind turbine blades. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 85, 309–324 (2000).

Xu, D., Liu, P. & Chen, Z. Damage mode identification and singular signal detection of composite wind turbine blade using acoustic emission. Compos. Struct. 255, 112954 (2021).

Tang, J., Soua, S., Mares, C. & Gan, T.-H. An experimental study of acoustic emission methodology for in service condition monitoring of wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 99, 170–179 (2016).

Yang, K., Rongong, J. A. & Worden, K. Damage detection in a laboratory wind turbine blade using techniques of ultrasonic NDT and SHM. Strain 54, e12290 (2018).

Oliveira, M. A. et al. Ultrasound-based identification of damage in wind turbine blades using novelty detection. Ultrasonics 108, 106166 (2020).

Hwang, S., An, Y.-K., Yang, J. & Sohn, H. Remote inspection of internal delamination in wind turbine blades using continuous line laser scanning thermography. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 7, 699–712 (2020).

Sanati, H., Wood, D. & Sun, Q. Condition monitoring of wind turbine blades using active and passive thermography. Appl. Sci. 8, 2004 (2018).

Chandrasekhar, K., Stevanovic, N., Cross, E. J., Dervilis, N. & Worden, K. Damage detection in operational wind turbine blades using a new approach based on machine learning. Renew. Energy 168, 1249–1264 (2021).

Regan, T., Beale, C. & Inalpolat, M. Wind turbine blade damage detection using supervised machine learning algorithms. J. Vib. Acoust. 139, 061010 (2017).

Joshuva, A. & Sugumaran, V. Crack detection and localization on wind turbine blade using machine learning algorithms: A data mining approach. Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 13, 181 (2019).

Xiaoxun, Z. et al. Research on crack detection method of wind turbine blade based on a deep learning method. Appl. Energy 328, 120241 (2022).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2961–2969 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, 21–37 (Springer, 2016).

Zhang, R. & Wen, C. Sod-yolo: A small target defect detection algorithm for wind turbine blades based on improved yolov5. Adv. Theory Simul. 5, 2100631 (2022).

Ran, X., Zhang, S., Wang, H. & Zhang, Z. An improved algorithm for wind turbine blade defect detection. IEEE Access 10, 122171–122181 (2022).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. Defect detection of the surface of wind turbine blades combining attention mechanism. Adv. Eng. Inform. 59, 102292 (2024).

Hu, Y., Wang, L., Kou, T. & Zhang, M. Yolo-tiny-attention: An improved algorithm for fault detection of wind turbine blade. In 2023 8th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), 1228–1232 (IEEE, 2023).

Liu, L., Li, P., Wang, D. & Zhu, S. A wind turbine damage detection algorithm designed based on yolov8. Appl. Soft Comput. 154, 111364 (2024).

Yu, H., Wang, J., Han, Y., Fan, B. & Zhang, C. Research on an intelligent identification method for wind turbine blade damage based on CBAM-BIFPN-YOLOV8. Processes 12, 205 (2024).

Tong, L. et al. WTBD-YOLOV8: An improved method for wind turbine generator defect detection. Sustainability 16, 4467 (2024).

Liu, Y., Yang, F. & Hu, P. Parallel FPN algorithm based on cascade R-CNN for object detection from UAV aerial images. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 57, 201505 (2020).

Wang, Y. Symposium title: The fronto-parietal network (FPN): Supporting a top-down control of executive functioning. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 168, S39 (2021).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Wang, F., Li, Z. & Sun, J. Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08430 (2021).

Wang, C.-Y., Yeh, I.-H. & Liao, H.-Y. M. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13616 (2024).

Ding, X. et al. Unireplknet: A universal perception large-kernel convnet for audio video point cloud time-series and image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5513–5524 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Carafe: Content-aware reassembly of features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 3007–3016 (2019).

Liu, W., Lu, H., Fu, H. & Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 6027–6037 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Yolov6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.02976 (2022).

Wang, C.-Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H.-Y. M. Yolov7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 7464–7475 (2023).

Wang, A. et al. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14458 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 16965–16974 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52005071 and the Applied Basic Research Program Project of Liaoning Province under Grant 2023JH2/101300236.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52005071 and the Applied Basic Research Program Project of Liaoning Province under Grant 2023JH2/101300236.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation. A. C. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing. X.Y. Conceptualization, Validation. Y.S. Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, L., Chen, A., Yang, X. et al. An improved method of AUD-YOLO for surface damage detection of wind turbine blades. Sci Rep 15, 5833 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89864-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89864-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing wind turbine blade damage detection with YOLO-Wind

Scientific Reports (2025)