Abstract

This article employed a bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to deduce the causal relationship between H. pylori infection (Seven H. pylori antibodies: CagA, Catalase, GroEL, IgG, OMP, UREA, and VacA) and allergic diseases. This study primarily employed the Inverse-Variance Weighted (IVW)method, supplemented by MR-Egger regression and the Weighted median (WM) method approach, to comprehensively assess the causal relationship between exposure and outcome. Sensitivity analysis, including Cochran’s Q test, MR-Egger regression intercept, MR-PRESSO test, and leave-one-out analysis, verified the reliability of the results. In the forward MR analysis, the IVW analysis outcomes showed the causal relationship existed between the allergic urticaria (AU) and Catalase antibody, allergic asthma (AA) and allergic rhinitis (AR) with OMP antibody, and allergic conjunctivitis (AC) and VacA antibody; in the reverse MR analysis, the results of the IVW analysis revealed that CagA antibody was positively associated with AU. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the causal relationship was robust. Higher levels of Catalase antibody may potentially increase the risk of AU development; increased OMP antibody levels might be associated with a higher risk for AA, yet could potentially be a protective factor against AR; greater VacA antibody levels might possibly decrease the incidence of AC; individuals with AU might have a higher likelihood of exhibiting elevated CagA antibody levels. It is suggested that H. pylori infection could potentially influence the onset and progression of allergic diseases via the “gut-skin”, “gut-lung”, “gut-nose”, and “gut-eye” axis; moreover, skin diseases may potentially impact the gut microbiota imbalance through the “skin-gut” axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic diseases refer to a group of heterogeneous disorders primarily triggered by the activation of specific immune cells under the mediation of Immunoglobulin E (IgE)1. These conditions predominantly affect organs such as the lungs, eyes, skin, and nasal, encompassing allergic asthma (AA), allergic conjunctivitis (AC), atopic dermatitis (AD), allergic rhinitis (AR), and allergic urticaria (AU)1. AA is a common chronic inflammatory airway disease characterized by reversible airflow limitation, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway remodeling, with clinical symptoms often featuring episodic wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath1. AC, an IgE-mediated inflammatory reaction of the conjunctiva, often begins in childhood and manifests as ocular dryness, itching, photophobia, excessive tearing, increased mucus production, and visual disturbances2. AD results from impaired skin barrier function and imbalances in the immune system, commonly showing symptoms of dry, itchy skin with accompanying eczema3. AR serves as a non-infectious inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa induced by allergens, presenting with nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, itching, and paroxysmal sneezing4. AU, a disease mediated by mast cells, is typified by pruritic wheals and angioedema5. Over the past three decades, there has been a significant rise in the prevalence of allergic diseases, affecting approximately 20% of the global population and impacting the quality of life for 80% of households6. Due to the complexity and increasing severity of allergic diseases, they have emerged as a significant public health concern on a global scale, resulting in a substantial economic burden. This surge in allergic conditions has led to increased healthcare utilization, medication costs, lost productivity, and reduced quality of life, all of which contribute to the overall financial implications for individuals, families, and healthcare systems worldwide. As such, addressing the growing challenge of allergic diseases requires concerted efforts in research, education, prevention, and management strategies to alleviate the burden and improve the well-being of those affected1,7.

The pathogenesis of allergic diseases is complex, involving environmental factors, genetic factors, microbiota, immune function, and other elements1. In recent years, the relationship between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and allergic diseases has gradually become a focus of research8,9. H. pylori, characterized by its unipolar, multiple flagella, blunt-rounded ends, and spiral curvature, is a Gram-negative aerobe which colonizes human gastric mucosa10. H. pylori infection represents a global health concern, affecting approximately half of the world’s population10. In 1994, the World Health Organization classified it as a Group 1 carcinogen, highlighting its central role in the development of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer, as well as its significant association with other gastrointestinal diseases10. Furthermore, as research continues to delve deeper, investigators have discovered that H. pylori infection can influence the occurrence and development of diseases outside the stomach, including those affecting the hematopoietic, cardiovascular, dermatological, neurological, and immunological systems, with particularly notable impacts on diseases of the nervous and immune systems10,11. Among these, a multitude of proteins play pivotal roles during H. pylori infection, especially cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), Catalase, GroEL, immunoglobulin G (IgG), outer membrane protein (OMP), urease subunit-A (UREA), and vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA). However, the relationship between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases is still controversial. Some studies have suggested that H. pylori infection may offer a certain degree of protective effect against AA8, but the latest research indicates that there is no significant correlation between H. pylori infection and AA9. These seemingly contradictory research findings suggest the complexity of the relationship between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases, as well as the necessity for further exploration in this field.

Mendelian Randomization (MR) is an emerging statistical method in epidemiology, using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (genetic variations) at the genomic level as instrumental variables (IVs) to intuitively and efficiently infer the causal relationship between exposure factors and phenotypes12. According to Mendel’s laws of inheritance, the distribution of genetic variations among individuals is random, and the formation of genotypes is typically not influenced by the progression of diseases before their onset13. Thus, MR can largely eliminate the impact of confounding factors. However, there has been no MR analysis report on the relationship between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases. Against this background, this article employs a bidirectional MR analysis to deduce the causal relationship between H. pylori infection (Seven H. pylori antibodies: CagA, Catalase, GroEL, IgG, OMP, UREA, and VacA) and allergic diseases.

Methods

Data sources

The datasets for H. pylori infection were obtained from the IEU Open genome-wide association studies (GWAS) project website (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), and all datasets consist of samples from European populations. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for these datasets were based on the serological measurements of infectious pathogens from the UK Biobank (UKB): First, pathogens with a seropositivity rate greater than 15% were selected to ensure sufficient statistical power. Second, antigen selection was based on their known biological functions and/or existing assay standards. Finally, antigen specificity was tested using the Luminex platform, comparing each pathogen-specific assay to a gold-standard reference test using independent reference sera. All detection methods demonstrated sensitivities and specificities above the pre-defined validation threshold of 85%, with median sensitivity and specificity of 97.0% and 93.7%, respectively. The sample sizes are as follows: CagA: 985, Catalase: 1558, GroEL: 2716, IgG: 8735, OMP: 2640, UREA: 2251, and VacA: 1571. The data on allergic diseases were also obtained from the same website and consist of European population samples, with case and control group sizes as follows: AA: 4859/131,051, AC: 9833/208,959, AD: 22,474/774,187, AR: 27,415/457,183, and AU: 1169/212,464. The summary information of GWAS data in MR analysis is presented in Table 1. All data utilized in this study were sourced from published research or public databases and therefore no separate ethical approval was required.

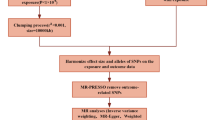

Study design

This study utilized summary data from GWAS to select SNPs significantly associated with the exposure as IVs, and employed a bidirectional MR analysis to explore the causal link between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases. The selection of IVs was based on three crucial assumptions14: (1) Relevance: the IVs are closely related to the exposure; (2) Independence: the IVs are not associated with any confounding factors related to the exposure-outcome association; (3) Exclusion restriction: the IVs affect the outcome only through the exposure. This study followed the bidirectional MR analysis method, which included (1) using H. pylori infection as the exposure to assess whether individuals with H. pylori infection were more prone to develop allergic diseases; and (2) using allergic diseases as the exposure to evaluate whether individuals with allergic diseases were more likely to develop H. pylori infection.

Selection of suitable IVs

The selection of IVs for the MR analysis must first adhere to the three pivotal assumptions outlined above. In forward MR analysis within this study, where H. pylori infection was the exposure and allergic diseases constitute the outcome, the criteria for selecting IVs were as follows: (1) setting a threshold of P < 5 × 10− 8 to identify SNPs significantly associated with H. pylori infection (seven H. pylori antibodies). If the number of SNPs identified served as less than three, the threshold was adjusted to P < 5 × 10− 6 for reselection15; (2) ensuring the IVs were independently inherited by excluding SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with a correlation coefficient r2 = 0.001 and a genetic distance of 10,000 kb14,15; (3) calculating the F statistic for each SNP to measure its strength as an IVs using the formula F = R2(N − K − 1) / K(1 − R2), aiming to select SNPs strongly associated with the exposure and independent of each other. SNPs with F ≥ 10 were considered strong IVs, and SNPs with F < 10 were excluded to avoid the influence of weak IVs16; (4) Searching for the initially selected IVs in the PubMed and PhenoScannerV2 databases to exclude those associated with confounding factors related to H. pylori infection and allergic diseases (such as age and antibiotic use) and using software to remove palindromic and incompatible SNPs17. The remaining SNPs were considered eligible IVs. In the reverse MR study, this research took allergic diseases as the exposure factor and H. pylori infection as the outcome, proceeding through the identical steps mentioned above to screen for suitable IVs.

MR analysis

This study primarily employed the Inverse-Variance Weighted (IVW) method, supplemented by MR-Egger regression and the Weighted median (WM) method approach, to comprehensively assess the causal relationship between exposure and outcome. The IVW method assumed that all SNPs were valid IVs with no pleiotropy, utilized the Wald ratio method to calculate the exposure-outcome effect for each SNP, and then applied weighted linear regression to combine the effect estimates of all SNPs, making it the preferred method for estimating causal impacts18,19. MR-Egger regression allowed for the presence of horizontal pleiotropy, used the reciprocal of the outcome variance as fitting weights in conjunction with IVW, could provide estimation results after identifying and correcting for potential pleiotropy, but performed less well in terms of statistical power compared to IVW20. The WM method combines data from multiple genetic variants into a single causal estimate and could serve as a supplementary method for effect assessment when the proportion of valid IVs exceeds 50%, but fails to fully utilize information from all IVs21.

Sensitivity analysis

To further validate the reliability of the MR analysis results, this study concurrently utilized Cochran’s Q test as a sensitivity analysis method22. A P-value greater than 0.05 suggests the absence of heterogeneity among the SNPs, the causal effect is assessed using the IVW fixed effects model. Conversely, a P-value less than 0.05 indicates the presence of heterogeneity, necessitating the application of the random-effects model in the IVW method to evaluate causal effects22. The intercept term from the MR-Egger regression and the MR-PRESSO test were employed to analyze horizontal pleiotropy among the SNPs15,23. A P-value less than 0.05 indicates the absence of horizontal pleiotropy. Additionally, a leave-one-out analysis was conducted to assess the influence of individual SNPs on the outcomes of the MR analysis, ensuring robustness and reliability of the results24.

Statistical analysis

The entire study was conducted using the “Two-sample-MR” package in the R software (version 4.1.2). The analysis results were expressed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI), with a two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was adopted as the nominal threshold.

Results

Forward MR analysis ofH. pylori infection on allergic diseases

Selection of IVs

In the forward analysis of this study, appropriate SNPs were finally included as IVs for the MR study after excluding linkage disequilibrium, F-value screening and removing confounding factors (P < 5 × 10− 6, F > 10) (Supplementary Excel file 1).

Causal effects of catalase antibody to allergic diseases

The IVW analysis outcomes indicated AU had a statistically significant association with Catalase antibody (OR = 1.188, 95% CI = 1.009-1.400, P = 0.039), while AA (OR = 1.005, 95% CI = 0.924–1.093, P = 0.908), AC (OR = 0.956, 95% CI = 0.891–1.026, P = 0.215), AD (OR = 1.015, 95% CI = 0.973–1.059, P = 0.484), and AR (OR = 1.001, 95% CI = 0.999–1.003, P = 0.521) did not show statistically significant associations with Catalase antibody (Fig. 1).

Causal effects of OMP antibody to allergic diseases

The IVW analysis results showed that AA (OR = 1.167, 95% CI = 1.003–1.357, P = 0.045) and AR (OR = 0.997, 95% CI = 0.995-1.000, P = 0.030) were statistically significant with OMP antibody, whereas AC (OR = 1.068, 95% CI = 0.962–1.186, P = 0.217), AD (OR = 1.063, 95% CI = 0.995–1.135, P = 0.068), and AU (OR = 1.200, 95% CI = 0.914–1.576, P = 0.189) did not show any correlation with OMP antibody (Fig. 1).

Causal effects of VacA antibody to allergic diseases

The IVW analysis outcomes demonstrated a causal relationship between AC and VacA antibody (OR = 0.946, 95% CI = 0.898–0.997, P = 0.039). However, no causal relationship were observed between AA (OR = 1.054, 95% CI = 0.980–1.134, P = 0.154), AD (OR = 1.007, 95% CI = 0.973–1.042, P = 0.698), AR (OR = 1.000, 95% CI = 0.999–1.002, P = 0.796), or AU (OR = 1.024, 95% CI = 0.888–1.181, P = 0.747) and VacA antibody (Fig. 1).

Causal effects of CagA, GroEL, IgG, and UREA antibodies to allergic diseases

The IVW analysis results indicated that there were no causal relationship between the five aforementioned allergic diseases and CagA, GroEL, IgG, and UREA antibodies (all P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). The forward MR analysis results of H. pylori infection on allergic diseases are shown in Supplementary Excel file 2.

Sensitivity analysis

The Cochran’s Q test results confirmed the absence of heterogeneity among the selected SNPs (all P > 0.05). The MR-Egger regression intercept and MR-PRESSO text showed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (all P > 0.05). The sensitivity analysis results for forward MR analysis are detailed in Supplementary Excel file 3. The leave-one-out analysis demonstrated that no significant outliers were observed after removing each SNP one by one (Fig. 2). The funnel plot of positive results in forward MR analysis are presented in Fig. 3.

Reverse MR analysis ofH. pylori infection on allergic diseases

Selection of IVs

In the reverse MR analysis, allergic diseases were set as exposure factors, while H. pylori infection were considered as the outcome. The thresholds were set consistent with those in forward study, and linkage disequilibrium was eliminated, ultimately selecting suitable IVs. Detailed information regarding the SNPs used in this analysis can be found in Supplementary Excel file 4.

Causal effects of AU to H. Pylori infection

The results of the IVW analysis revealed that CagA antibody was positively associated with AU (OR = 1.179, 95% CI = 1.023–1.358, P = 0.023), while the other six antibodies showed no association with AU (all P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Causal effects of AA, AC, AD, and AR to H. Pylori infection

The IVW analysis results indicated that there were no evidence of a causal relationship between H. pylori infection and AA, AC, AD, and AR (all P > 0.05) (Fig. 4). The reverse MR analysis results of H. pylori infection on allergic diseases are shown in Supplementary Excel file 5.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of Cochran’s Q test, MR-Egger regression intercept, and MR-PRESSO text indicated no significant heterogeneity or potential horizontal pleiotropy (all P > 0.05). The sensitivity analysis results for reverse MR analysis are detailed in Supplementary Excel file 6. Leave-one-out analysis showed that sequentially removing SNP did not have a significant impact on the causal relationship between the two (Fig. 2). The funnel plot of positive results in reverse MR analysis is presented in Fig. 3.

Discussion

In recent years, the incidence of allergic diseases has been on the rise globally, paralleled by growing research into the relationship between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases6,8,9. However, the precise nature of this association remains a subject of considerable debate. This study employed publicly available GWAS data for a bidirectional MR analysis to explore the potential causal links between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases. The forward MR analysis revealed that elevated levels of Catalase antibody might increase the risk of developing AU; increased OMP antibody levels might pose a risk factor for AA but could serve as a protective factor against AR; higher VacA antibody levels might reduce the incidence of AC. Conversely, the reverse MR analysis indicated that individuals with AU are more likely to exhibit heightened CagA antibody levels. All findings were robustly validated through sensitivity analysis, including Cochran’s Q test, MR-Egger regression intercept, MR-PRESSO test, and leave-one-out analysis. To date, this is the first study utilizing a bidirectional MR approach to investigate the relationship between H. pylori infection and allergic diseases.

The study found through forward MR analysis that H. pylori infection might influence the occurrence and development of allergic diseases through complex networks involving the “gut-skin” axis, “gut-lung” axis, “gut-nose” axis, and “gut-eye” axis. Currently, there is no report on the exact relationship between Catalase antibody and AU, but this study found that elevated levels of Catalase antibody might increase the risk of developing AU. Previous reports have highlighted the interaction between gut microbiota and the skin, which may be associated with the regulation of the “gut-skin” axis25. The gut microbiome influences the overall skin homeostasis significantly through interactions with key immune cells such as mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils, as well as changes in metabolic activities. Catalase proteins are widely present in mammalian cells, playing a crucial role in protecting against the oxidative damage inflicted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) on H. pylori and in maintaining the balance of oxygen metabolism26,27. An increase in Catalase antibody expression might lead to a “cascade activation” of both local and systemic immune systems, releasing more vasodilatory mediators that can stimulate the skin and predispose patients to the manifestation of cutaneous symptoms28,29. Currently, there is no direct evidence establishing a causal relationship between OMP antibody levels and AA, and there is controversy regarding the association between H. pylori infection and AA8,9. However, the existing studies are based on observational research or basic research. Observational studies cannot control potential confounding factors, such as age, lifestyle, and unknown influencing factors, as effectively as randomized controlled trials, and they may be limited by insufficient sample sizes, leading to unreliable conclusions. Cell experiments are typically conducted in vitro and cannot fully replicate the complex physiological environment of the body; differences in culture conditions compared to in vivo environments may lead to experimental results that do not match reality, and these results may not be directly applicable to more complex biological systems. Animal models require significant time and financial investment, and there are ethical controversies surrounding their use; additionally, there are significant genetic, metabolic, and immunological differences between animals and humans, which may limit the extrapolation of experimental results to humans. However, this study uses MR analysis to avoid the influence of confounding factors and increases the sample size. The results suggest that OMP antibodies was a risk factor for AA, and the “gut-lung axis " may play a significant role in this process. OMP antibody may lead to epithelial barrier dysfunction, oxidative stress, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, activating various inflammatory mediators such as H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, inducing the activation of dendritic cells (DCs), causing TH1/TH2 imbalance, promoting the occurrence of inflammatory responses and amplifying the “cascade” inflammatory response30,31. AA is associated with inflammation, cellular infiltration, airway hyperresponsiveness, and varying degrees of epithelial cell damage1. Therefore, the upregulation of OMP antibody might be a risk factor for the development of AA.

At present, the specific role of OMP antibody in AR remains largely unexplored, whereas the results of this study showed that OMP antibody might be a protective factor against AR. Increasing evidence indicates that “gut-nose” axis might exist, which regulates microbiota-immune interactions through the exchange of information on mucosal surfaces32. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), one of the most abundant products of gut microbial metabolism, may exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting Th17 cells, modulating the secretion of cytokines such as interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-10, reducing the activation of DCs, and increasing the secretion of regulatory T (Treg) cells33; the upregulation of OMP antibody might activate these anti-inflammatory signaling pathways through SCFAs, thereby exerting immunomodulatory effects and potentially reduce susceptibility to AR. Currently, research regarding the relationship between VacA antibody and AC is limited, but the results of this study indicated that VacA antibody might serve as a protective factor against AC. This finding indirectly supported the concept of the “gut-eye” axis, suggested that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota could be a significant factor influencing various ocular diseases and systemic immune responses. VacA, one of the primary toxins secreted by H. pylori, has been associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, induction of cell apoptosis, inhibition of T cell proliferation, and promotion of Treg cells34,35. Research has shown that an upregulation of VacA antibody might activate the Foxp3 pathway, induce the development of local and peripheral Treg cells, inhibit the proliferation of effector T cells, and simultaneously promote the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators and factors such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta35,36; therefore, this antibody upregulation could alleviate clinical symptoms in AC.

The results of the reverse MR analysis in this study showed that the occurrence of AU was a risk factor associated with elevated levels of CagA antibody in the body. This suggested that the emergence of skin diseases might affect the imbalance of gut microbiota, a pathway referred to as the “skin-gut” axis. The study points out that AU is usually triggered by skin contact with allergens, which induces mast cell degranulation, leading to an increase in eosinophils and neutrophils, as well as the release of a series of chemokines, cytokines, and inflammatory mediators; these changes reshape the inflammatory microenvironment of the stomach, activating ROS pathways and inhibiting tyrosinase and other pathways related to cell apoptosis25,37. Such alterations might upregulate CagA protein expression, significantly enhancing cell proliferation and pathogenicity, increasing the likelihood of H. pylori evading immune responses and inducing inflammatory responses in the gastrointestinal tract38.

This study also revealed that no causal relationships exist between other H. pylori-related antibodies and other allergic diseases. Previous research has suggested that the upregulation of CagA antibody might reduce the risk of AA39,40. However, such studies are predominantly observational in nature and may be susceptible to interference from unknown confounding factors, potentially affecting the accuracy of their results. In contrast, the bidirectional MR study method employed in this research effectively mitigates the influence of potential confounding factors. Moreover, the consistency of findings across three distinct analytical approaches further reinforces the robustness of the study conclusions. Nevertheless, to definitively establish causal associations, larger-scale GWAS and clinical investigations are warranted.

This study boasts several strengths: it innovatively investigated the potential causal associations between seven H. pylori-related antibodies and five types of allergic diseases, addressed a gap in current research; the rigorous sensitivity analysis had enhanced the reliability of the study results. However, this study also has some limitations: Firstly, although MR analysis has detected and corrected some horizontal pleiotropy through sensitivity analysis, it cannot completely exclude other potential pleiotropic effects, such as the selected SNPs not only affecting the exposure variable through the predetermined mediating pathways but also potentially interfering with the results through other unknown or unconsidered pathways; moreover, it can only eliminate the interference of known confounding factors based on existing literature, and cannot rule out the influence of unknown confounding factors. Secondly, the data for this study are based solely on European samples and lack representation of non-European populations, rendering the results potentially non-generalizable to non-European populations due to genetic, environmental, or lifestyle differences. Finally, given that serological tests may have multiple possible interpretations, it is impossible to completely avoid the false positive rate or false negative rate of the data, and especially when the antibody titer is low, cross-reactions caused by the overlap of certain antibodies (such as catalase) with the gut microbiota are inevitable. In the future, it is necessary to implement retrospective experiments and prospective trials, involve more diverse populations, expand sample size, incorporate strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, and enhance the universality and credibility of the conclusions.

Conclusion

Higher levels of Catalase antibody may potentially increase the risk of AU development; increased OMP antibody levels might be associated with a higher risk for AA, yet could potentially be a protective factor against AR; greater VacA antibody levels might possibly decrease the incidence of AC; individuals with AU might have a higher likelihood of exhibiting elevated CagA antibody levels. It is suggested that H. pylori infection could potentially influence the onset and progression of allergic diseases via the “gut-skin”, “gut-lung”, “gut-nose”, and “gut-eye” axis; moreover, skin diseases may potentially impact the gut microbiota imbalance through the “skin-gut” axis.

Data availability

The datasets were obtained from the IEU Open genome-wide association studies (GWAS) project website (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). (CagA, ebi-a-GCST90006911; Catalase, ebi-a-GCST90006912; GroEL, ebi-a-GCST90006913; IgG, ebi-a-GCST90006910; OMP, ebi-a-GCST90006914; UREA, ebi-a-GCST90006915; VacA, ebi-a-GCST90006916; Allergic asthma, finn-b-ALLERG_ASTHMA_EXMORE; Allergic conjunctivitis, finn-b-H7_ALLERGICCONJUNCTIVITIS; Atopic dermatitis, ebi-a-GCST90027161; Allergic rhinitis, ebi-a-GCST90038664; Allergic urticaria, finn-b-L12_URTICA_ALLERG).

References

Wang, J. et al. Pathogenesis of allergic diseases and implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 (1), 138 (2023).

Iordache, A. et al. Relationship between allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis) - review. Rom J. Ophthalmol. 66 (1), 8–12 (2022).

Ständer, S. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl. J. Med. 384 (12), 1136–1143 (2021).

Bousquet, J. et al. Allergic rhinitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 6 (1), 95 (2020).

Gaudinski, M. R. & Milner, J. D. Atopic dermatitis and allergic urticaria: cutaneous manifestations of Immunodeficiency. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North. Am. 37 (1), 1–10 (2017).

Dierick, B. J. H. et al. Burden and socioeconomics of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 20 (5), 437–453 (2020).

Perry, T. T., Grant, T. L., Dantzer, J. A., Udemgba, C. & Jefferson, A. A. Impact of socioeconomic factors on allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 153 (2), 368–377 (2024).

Zuo, Z. T. et al. The Protective effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on allergic asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 182 (1), 53–64 (2021).

Dore, M. P., Meloni, G., Bassu, I. & Pes, G. M. Helicobacter pylori Infection Does Not Protect Against Allergic Diseases: Evidence From a Pediatric Cohort From Northern Sardinia, Italy. Helicobacter. 29(3):e13107. (2024).

Malfertheiner, P. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9 (1), 19 (2023).

Moss, S. F., Shah, S. C., Tan, M. C. & El-Serag, H. B. Evolving concepts in Helicobacter pylori Management. Gastroenterology 166 (2), 267–283 (2024).

Larsson, S. C., Butterworth, A. S. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: principles and applications. Eur. Heart J. 44 (47), 4913–4924 (2023).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology using mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA 326 (16), 1614–1621 (2021).

Spiga, F. et al. Tools for assessing quality and risk of bias in mendelian randomization studies: a systematic review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52 (1), 227–249 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Use of bidirectional mendelian randomization to unveil the association of Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Sci. Adv. 10 (31), eadi8646 (2024).

Rees, J. M. B., Foley, C. N. & Burgess, S. Factorial mendelian randomization: using genetic variants to assess interactions. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49 (4), 1147–1158 (2020).

Kamat, M. A. et al. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype-phenotype associations. Bioinformatics 35 (22), 4851–4853 (2019).

Mounier, N. & Kutalik, Z. Bias correction for inverse variance weighting mendelian randomization. Genet. Epidemiol. 47 (4), 314–331 (2023).

Deng, Y., Huang, J. & Wong, M. C. S. Associations between six dietary habits and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a mendelian randomization study. Hepatol. Commun. 6 (8), 2147–2154 (2022).

Rees, J. M. B., Wood, A. M. & Burgess, S. Extending the MR-Egger method for multivariable mendelian randomization to correct for both measured and unmeasured pleiotropy. Stat. Med. 36 (29), 4705–4718 (2017).

Mazidi, M. et al. The association between coffee and caffeine consumption and renal function: insight from individual-level data, mendelian randomization, and meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 18 (4), 900–911 (2021).

Bowden, J. & Holmes, M. V. Meta-analysis and mendelian randomization: a review. Res. Synth. Methods. 10 (4), 486–496 (2019).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Interpreting findings from mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 32 (5), 377–389 (2017).

Gronau, Q. F. & Wagenmakers, E. J. Limitations of bayesian leave-one-out Cross-validation for Model Selection. Comput. Brain Behav. 2 (1), 1–11 (2019).

Kemter, A. M. & Nagler, C. R. Influences on allergic mechanisms through gut, lung, and skin microbiome exposures. J. Clin. Invest. 129 (4), 1483–1492 (2019).

López, M. B., Oterino, M. B. & González, J. M. The Structural Biology of Catalase Evolution. Subcell. Biochem. 104, 33–47 (2024).

Wu, S. et al. Reactive oxygen species and gastric carcinogenesis: the complex interaction between Helicobacter pylori and host. Helicobacter 28 (6), e13024 (2023).

Andrade, R. D. S. et al. Antioxidant defense of children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis: Association with disease severity. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr). 52 (1), 65–70 (2024).

Mahmud, M. R. et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 14 (1), 2096995 (2022).

Fu, H. W. & Lai, Y. C. The role of Helicobacter pylori Neutrophil-activating protein in the pathogenesis of H. Pylori and Beyond: from a virulence factor to therapeutic targets and therapeutic agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (1), 91 (2022).

FitzGerald, R. & Smith, S. M. An overview of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2283, 1–14 (2021).

Dong, L. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates allergic Rhinitis via CD4 + T cell modulation through gut microbiota restoration. Inflammation 47 (4), 1278–1297 (2024).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Parthenolide ameliorates colon inflammation through regulating Treg/Th17 balance in a gut microbiota-dependent manner. Theranostics 10 (12), 5225–5241 (2020).

Sáenz, J. B. Early Recagnition: CagA-specific CD8 + T cells shape the Immune response to Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 164 (4), 520–521 (2023).

Reuter, S. et al. Treatment with Helicobacter pylori-derived VacA attenuates allergic airway disease. Front. Immunol. 14, 1092801 (2023).

El-Badawy, M. A. B., Sayed, O., Ibrahim, D. M., Seif-Eldin, M. A. E. A. M. & Thabit, S. S. Relation of Regulatory Foxp3 + T cells with Helicobacter pylori and its virulence genes. Egypt. J. Immunol. 25 (1), 9–17 (2018).

Maurer, M., Zuberbier, T. & Metz, M. The classification, Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Workup, and management of Urticaria: an update. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 268, 117–133 (2022).

Muzaheed Helicobacter pylori Oncogenicity: Mechanism, Prevention, and Risk Factors. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020: 3018326. (2020).

Chen, Y., Zhan, X. & Wang, D. Association between Helicobacter pylori and risk of childhood asthma: a meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. J. Asthma 59 (5), 890–900 (2022).

Saeed, N. K., Al-Beltagi, M., Bediwy, A. S., El-Sawaf, Y. & Toema, O. Gut microbiota in various childhood disorders: implication and indications. World J. Gastroenterol. 28 (18), 1875–1901 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The author heartfeltly thanks the researchers who conduct GWAS studies and openly shared their summary statistics.

Funding

This study was supported by the Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology (project number:20-4-1-5-nsh).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng Hai Qu designed the studies; Guo Zhen Fan, Bo Yang Duan and Fang jie Xin analysed the data; and all authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All data utilized in this study were sourced from published research or public databases and therefore no separate ethical approval was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, G.Z., Duan, B.Y., Xin, F.j. et al. Assessment of the bidirectional causal association between Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic diseases by mendelian randomization analysis. Sci Rep 15, 5746 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89981-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89981-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Update on the Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Children and Adolescents

Current Gastroenterology Reports (2025)

-

Assessment of the bidirectional causal association between allergic diseases and neuropsychiatric disorders

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2025)