Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is notorious for its high likelihood of recurrence even after radical surgery, which calls for effective adjuvant therapy based on more precise patient selection. The decline of the abundance of binuclear hepatocytes (ABH) in paracancerous liver tissues has been reported to indicate pathological changes in liver cells, leading to short-term recurrence within 2 years. In this research, we analyzed 34 HCC patients and 22 patients underwent liver surgery for non-HCC diseases. An ImageJ script was used to assess binuclear hepatocytes in the HE-staining specimens of paracancerous liver tissues. ABH significantly decreased in HCC patients and indicated poorer outcomes. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays suggested ploidy-related regulation of arginase 1 (ARG1) expression. Our findings suggested computer-assisted assessment of ABH as a possible biomarker for short-term HCC recurrence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the world’s fourth leading cause of tumor-related death, accounting for 90% of primary liver cancers1,2. Although the developments in targeted and immunotherapy have shed new light on the treatment strategy for HCC, the overall survival of HCC patients remained dismal. The medium recurrence-free survival (RFS) of HCC patients after surgery is only 22 months3. Even for patients with relatively early stages of disease eligible for radical surgery, 20% of them still experience tumor relapse within 2 years3. Short-term recurrence has been described to correlate with multiple genetic alterations4,5, and is related to poorer treatment outcomes and worse characteristics of the tumor6,7,8. Adjuvant therapy after surgery can help to reduce the recurrence rate and control disease progression, but currently, there’s no standard criteria for patient selection. New prognostic factors may help in clinical decision-making by improving patient stratification.

Remaining microsatellitosis is a major cause of tumor relapse within 2 years9. The well-known ‘Seed and Soil’ theory of tumor progression emphasizes the change in the microenvironment in tumor metastasis and relapse. According to it, the microenvironment in paracancerous tissue experiences fundamental changes during tumor invasion, modifying them into suitable ‘soil’ in order to support the tumor ‘seeds’10. In the case of HCC, although there’s already much research discussing the relationship between tumor characteristics, satellitosis, and recurrent risk, few attempts were made to investigate the role of ‘soil’ in satellite lesions formation and tumor relapse.

The normal tissue of the liver is most characterized by its programmed polyploidization. The majority of human somatic cells are diploid cells with two sets of chromosomes (2n), while 20%~50% of hepatocytes are polyploid cells, with 70% of them being binuclear tetraploid cells (2 × 2n)11,12,13. The accumulation of polyploid hepatocytes is mainly caused by frequent cytokinesis failure during mitosis14. Some researchers have pointed out that the additional chromosomes in polyploid hepatocytes serve as a protective mechanism against carcinogenesis by preventing loss of heterozygosity (LOH)15. This hypothesis is supported by the findings that E2F7−/−E2F8−/− mice with predominantly 2n hepatocytes showed a higher risk of HCC after diethyl nitrosamine (DEN) challenge, while PIDDosome defective polyploidization model mice experienced less tumor burden after DEN challenge15,16,17.

In pathological conditions, the polyploid hepatocytes can produce offspring with reduced ploidy through multipolar mitosis18. Although ploidy reversal of hepatocytes is important in tissue repair and regeneration, chronic liver injuries such as viral infection and cirrhosis can lead to atypical regulation of ploidy in hepatocytes, resulting in the reduction of binuclear hepatocytes12,19. We have recently reported that the abundance of binuclear hepatocytes (ABH) in paracancerous tissue is a promising prognostic biomarker for HCC short-term recurrence after radical surgery20.

Compared with flow cytometry or single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq), ABH is a more publicizable indicator for ploidy changes in liver tissues since it can be assessed with regular hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stained samples used in pathology diagnostic procedures. However, manually counting binuclear hepatocytes is labor-intensive and difficult to reproduce, limiting its use in clinical settings. Previously, Desdouets et al. applied ImageJ, an image analysis software, to assess the ploidy of hepatocytes by measuring the fluorescent area in Hoechst-stained hepatocytes21. In this article, we developed a computer-assisted assessment procedure for assessing ABH in HE-stained samples and tested its efficiency in predicting the short-term recurrence of HCC.

Results

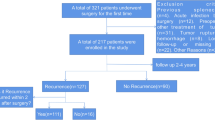

The clinicopathological features of patients

Table 1 shows the clinicopathological features of the 73 patients enrolled in this study. Features such as age, gender, HBV and HCV infection, cirrhosis, maximum tumor diameter and the number of tumors, portal thrombosis, microvascular invasion (MVI), neotherapy, protein induced by vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II) level, and BCLC staging were comparable between the recurred and not recurred groups.

ImageJ-assisted assessment of ABH showed consistent results with pABH

ABH was defined as the proportion of binuclear hepatocytes in total hepatocytes (Fig. 1), as previously described20. As shown in Fig. 2A–C, the exact number of total hepatocytes and binuclear hepatocytes and the calculated number of ABH were individually compared between pathologists-counted results and ImageJ-generated results. Computer-generated value of ABH (cABH) showed almost identical results when correlated with the pathologists counted value of ABH (pABH), with the slope of 0.8759 ± 0.04122, intercept at 0.5164 ± 0.2647, and R2 = 0.8641.

Procedure of computer-assisted identification of binuclear hepatocytes. (A) An example of the original footage before ImageJ processing. The white balance was deliberately tweaked for better contrast between nuclear and cytoplasm. (B) The original picture was gray-scaled and Gaussian smoothed to select the nuclear. (C) The binarized figure shows nuclear, with overlapping nuclear divided. (D) The final result after ImageJ processing of the example figure. Blue circles represent hepatocyte nuclear, and pairs of yellow circles represent binuclear hepatocytes.

Comparison of pathologist and computer-assisted counting of hepatocytes. (A–C) The linear regression of the pathologists counted number and the ImageJ-generated number of total hepatocytes, binuclear hepatocytes, and ABH. The residual plot shows the distribution of each model’s residual. (D) The ROC curve of using cABH<4% to predict pABH<4%. (E) Typical images showing side-by-side comparison of pathologist-counted hepatocytes (normal: blue square, binuclear: yellow square) and ImageJ labeled hepatocytes (normal: blue circle, binuclear: yellow circle).

We chose ABH < 4% as the threshold for reduced ABH based on pABH. cABH yielded similar results in identifying patients with reduced ABH in univariable logistic regression (OR = 46.67, 95%CI = 12.55–238.6, AUC = 86.05%, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D). A typical comparison between manually and ImageJ-labeled binuclear hepatocytes showed similar results (Fig. 2E). These results supported the reliability of our script.

ABH is reduced in HCC and slightly reduced in other liver cancer

When comparing between ABH from patients with benign, HCC and other liver malignancies, ABH values were significantly different among groups (Fig. 3A,G). ABH from HCC patients is lowest in all three groups (pABH: 4.348 ± 2.736, cABH: 4.224 ± 2.409). Interestingly, although ABH from patients with liver cancer other than HCC (pABH: 6.793 ± 3.403, cABH: 6.513 ± 3.488) is higher than those from patients with HCC, it is still significantly lower than that of benign diseases (pABH: 11.49 ± 4.504, cABH: 11.5 ± 3.777). Our findings showed that ABH is reduced in various types of malignancies, with HCC outstanding from others in reduction rate.

ABH is related to various clinicopathological features. (A, G) The comparison of average ABH among patients with benign disease, non-HCC malignancy and HCC, using pABH or cABH individually. pABH: Benign ABH = 11.49 ± 4.504%, non-HCC malignancy ABH = 6.793 ± 3.403%, HCC ABH = 4.348 ± 2.736%. Benign vs. HCC p<0.0001, Benign vs. Non-HCC malignancy p = 0.0097, HCC vs. non-HCC malignancy p = 0.0188. cABH: Benign ABH = 11.5 ± 3.777%, non-HCC malignancy ABH = 6.513 ± 3.488%, HCC ABH = 4.224 ± 2.409%. Benign vs. HCC p<0.0001, Benign vs. Non-HCC malignancy p = 0.0022, HCC vs. non-HCC malignancy p = 0.0158. (B–F, H–L) The comparison of ABH in HCC patients with different clinicopathological characters. cABH and pABH were compared individually. (B, H) Patients who relapsed within 2 years or not. pABH: recurrence- ABH = 5.427 ± 3.127%, recurrence + ABH = 3.313 ± 2.207%, p = 0.0232. cABH: recurrence- ABH = 5.269 ± 2.614%, recurrence + ABH = 3.258 ± 1.891%, p = 0.0109. (C, I) Patients within groups of BCLC 0-A, or BCLC B. pABH: BCLC 0-A ABH = 4.887 ± 3.198%, BCLC B ABH = 3.65 ± 1.721%, p = 0.2734. cABH: BCLC 0-A ABH = 4.673 ± 2.733%, BCLC B ABH = 3.878 ± 1.622%, p = 0.4118. (D, J) Patients with or without liver cirrhosis. pABH: cirrhosis- ABH = 6.548 ± 4.027%, cirrhosis + ABH = 4.482 ± 2.985%, p = 0.0163. cABH: cirrhosis- ABH = 6.418 ± 3.863%, cirrhosis + ABH = 4.281 ± 2.681%, p = 0.008. (E, K) Patients who have or haven’t received neoadjuvant therapy. pABH: neotherapy- ABH = 4.592 ± 2.906%, neotherapy + ABH = 3.156 ± 1.163%, p = 0.1534. cABH: neotherapy- ABH = 4.433 ± 2.528%, neotherapy + ABH = 3.202 ± 1.399%, p = 0.1646. (F, L) Comparison of ABH between ARG1 low, medium and high positive groups. pABH: low positive ABH = 4.109 ± 3.610, medium positive ABH = 4.207 ± 2.097, high positive ABH = 11.34 ± 1.9, p = 0.0023. cABH: low positive ABH = 4.106 ± 2.882, medium positive ABH = 4.313 ± 1.94, high positive ABH = 9.465 ± 2.22, p = 0.011. (M) Example of ABH (labeled with yellow square) in ARG1 high positive (left) and low positive tissues (right).

ABH is lower in HCC patients with short-term recurrence

Student’s t-test showed that ABH in HCC patients experienced short-term recurrence within 2 years after surgery is significantly reduced compared with other HCC patients (Fig. 3B, H). While the average ABH from patients without short-term recurrence is 5.427 ± 3.127 and 5.269 ± 2.614, the average ABH from patients who experienced relapse within 2 years is only 3.313 ± 2.207 and 3.258 ± 1.891 for pABH and cABH, respectively. The difference is significant (p = 0.0232 and 0.0109) in both results from pathologists and ImageJ, demonstrating a clear reduction of ABH in HCC patients with short-term recurrence.

ABH is lower in patients with liver cirrhosis

Of all the enrolled patients, 42 were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis before surgery (Table 1). The comparison between patients with and without liver cirrhosis was made to investigate the theory that binuclear hepatocytes are reduced in chronic liver diseases. ABH was proven to be significantly reduced under liver cirrhosis conditions compared with normal liver (No cirrhosis: pABH = 6.548 ± 4.027 and cABH = 6.418 ± 3.863, Cirrhosis: pABH = 4.482 ± 2.985 and cABH = 4.281 ± 2.681, p = 0.0163 and 0.009) (Fig. 3D, I).

The relation between ABH and other clinical features was also investigated. ABH was similar between groups divided by alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), PIVKA-II, HBV, HCV, MVI, and portal thrombosis (data not shown). HCC patients who underwent neotherapy and those in more advanced stages according to BCLC criteria have lower ABH than the other corresponding groups, although statistical significance was not reached (pABH: BCLC 0-A: 4.887 ± 3.198, BCLC B-C: 3.650 ± 1.721, p = 0.2734; neotherapy-: 4.592 ± 2.906, neotherapy+: 3.156 ± 1.163, p = 0.1537. cABH: BCLC 0-A: 4.673 ± 2.733, BCLC B-C: 3.878 ± 1.622, p = 0.4118; neotherapy-: 4.433 ± 2.528, neotherapy+: 3.202 ± 1.399, p = 0.1646) (Fig. 3C, E, I, K).

ABH is reduced in ARG1 low-positive tissues

We also compared the paired immunohistochemistry (IHC) samples with HCC patients’ ABH to find a possible link between ABH reduction and protein expression of hepatocytes in paracancerous tissues. We noticed the ABH reduction is related to lower arginase 1 (ARG1) expression, an enzyme involved in the urea cycle primarily expressed in hepatocyte cytoplasm. The ABH among low, medium, and high ARG1 expression groups were 4.109 ± 3.610, 4.207 ± 2.097, 11.34 ± 1.9 for pABH and 4.106 ± 2.882, 4.313 ± 1.94, 9.465 ± 2.22 for cABH, p = 0.0023 and 0.011, respectively (Fig. 3F, L). ARG1 high expression paracancerous liver tissues showed significantly higher ABH than both the other two groups (Fig. 3M).

ABH reduction is an independent risk factor for short-term recurrence after surgery in HCC patients

Since ABH is lower in HCC patients who experienced tumor relapse within 2 years after surgery, we wondered if ABH could serve as a prognostic factor in the treatment of HCC. Multivariable and univariable logistic regression were performed in both pABH and cABH and other clinicopathological features. HCV and portal thrombosis positive were excluded from investigation due to perfect separation in our data. Multivariable regression with pABH and cABH was done separately with other variables.

Univariable logistic regression identified pABH, cABH, and BCLC as independent risk factors for HCC short-term recurrence (Table 2; Fig. 4A, B). The OR of pABH is 0.7043 (0.4853–0.9245), and cABH is 0.6125 (0.3857–0.8606). The OR of BCLC was 3.652 (1.427–11.53). The area under curve (AUC) was 70.27% (p = 0.0203), 74.46% (p = 0.0051), and 68.11% (p = 0.0239) for pABH, cABH, and BCLC regression. AFP, tumor number, and the history of neotherapy also showed meaningful OR (AFP: 5, 1.16–34.92; tumor number: 2.028, 1.138–4.649; neotherapy: 9.412, 1.374–188.1), although AUCs were not statistically significant (p = 0.1306, 0.135, 0.2193, respectively) (Fig. 4B).

Prognostic values of ABH for the short-term recurrence of HCC after radical surgery. (A) The univariable logistic regression of pABH, cABH, and BCLC on 2-year recurrence. (B) The forest plot of univariable logistic regression shows each variable’s OR under logarithmic scale. (C, D) The multivariable logistic regressions and the paired forest plots of pABH and cABH with the history of neotherapy, BCLC, tumor number and AFP. E. The Kaplan–Meier survival plot of HCC patients of ABH ≥ 4% group or ABH<4% group. pABH and cABH were plotted individually. (F, G) The heat map and volcano plot shows DEGs in HCC tissues and normal liver tissues. ARG1 is highly expressed in both types of tissues while being slightly down-regulated in HCC tissues. (H) The survival plot of HCC patients with high or low ARG1 expression. No significant difference was achieved. (I) The survival plot of late-stage (BCLC C) HCC patients with high or low ARG1 expression. The medium survival period of the ARG1-low group is 21.6 months, comparing with 40.3 months in the ARG1-high group (p = 0.05).

Multivariable logistic regressions with those factors were performed to test our results (Table 3; Fig. 4C,D). pABH, cABH, and AFP were confirmed as risk factors for HCC short-term recurrence. Only ABH was identified as an independent risk factor for short-term recurrence (Fig. 4C, D). The OR of pABH and cABH were 0.726 (0.4669–0.9933) and 0.6134 (0.35–0.9075), respectively. The AUC of the two models were 77.19% (p = 0.0019) and 79.92% (p = 0.0006) for regression involving pABH and cABH. Our findings suggested ABH may serve as a potential prognostic risk factor for HCC short-term recurrence.

RFS of patients with ABH < 4% is significantly lower

After finding ABH as the independent risk factor for short-term recurrence, we further tested if the cut-off value at ABH = 4% can separate patients with different outcomes. Survival analysis was performed with both pABH and cABH, both resulted in significantly worse RFS of HCC patients in ABH < 4% groups (p = 0.03642 and p = 0.02380) (Fig. 4E). The median RFS of patients in ABH < 4% groups were 23 months and 18 months for pABH and cABH. Our findings further promoted ABH as an efficient prognostic risk factor for HCC patients undergoing radical surgery.

ARG1 is down-regulated in HCC tissues and is related to worse OS of late-stage patients

Since we discovered a possible relationship between hepatocyte ploidy and ARG1 expression, we further performed the differentially expressed genes (DEG) tests in TCGA datasets (Suppl. Figure 1). ARG1 was found to be significantly down-regulated in HCC tumor tissues compared with normal liver tissues (Fig. 4F, G, Suppl. Figure 1, log2(fold-change = −1.095316, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, although ARG1 wasn’t a risk factor for OS in all-stage HCC (Fig. 4H, p = 0.13), lower ARG1 was significantly related to shorter OS in BCLC C-stage HCC patients (Fig. 4I, p = 0.05).

ABH is capable of identifying patients with higher risk of recurrence not recommended with adjuvant therapy in current clinical practice

Adjuvant therapy can help to prevent the relapse of tumors or control disease progression in HCC patients. To find out whether ABH can improve current clinical practice, we tested the rate of patients with ABH < 4% in HCC patients grouped by short-term recurrence and whether they were recommended adjuvant therapy.

ABH was noticeably higher in patients who were not recommended for adjuvant therapy but experienced tumor recurrence later, compared with those who didn’t receive adjuvant therapy nor experienced tumor recurrence (pABH: 83.33% vs. 27.27%; cABH: 66.67% vs. 27.27%) (Fig. 5A–D). Importantly, ABH was consistent between patients recommended for or against adjuvant therapy in both groups of recurred or not recurred, showing good reliability of our model.

Reduction of ABH predicts short-term recurrence after surgery in patients haven’t been recommended adjuvant therapy by current standards. (A, B) The percentage of pABH < 4% patients in short-term recurrence group and no recurrence group, with or without adjuvant therapy. (C, D) The percentage of cABH < 4% patients in short-term recurrence group and no recurrence group, with or without adjuvant therapy.

Discussion

HCC is one of the most common malignancies worldwide. Surgery is the most important curative treatment for early- or intermediate-stage HCC patients22. However, the outcomes of HCC patients receiving radical surgery are still unsatisfactory, as the medium RFS is limited to 22 months3 and 2 year RFS rate is only 80% 3. In the last few years, advancements in targeted and immune therapy have greatly improved the outcomes of intermediate- and late-stage HCC patients23. To better integrate the progression of systematic therapies into the comprehensive treatment strategy based on radical surgery, precise adjuvant treatments for patients with high risk of recurrence are necessary.

The programmed polyploidization of hepatocytes is a distinctive characteristic in healthy liver tissues. Researchers have reported that hepatocytes are almost exclusively diploid in rodents after birth and the proportion of polyploid hepatocytes grows rapidly during weening24. Polyploid hepatocytes are mainly formed by endomitosis, in which the proliferating 2n cell enters M stage but fails to complete cytokinesis, resulting in a 2 × 2n binuclear polyploid offspring14. Complex regulating mechanisms are involved in maintaining hepatocyte ploidy by modulating cell cycle and DNA damage response (DDR) pathways, similar to mechanisms commonly found in tumorigenesis such as E2F family genes (E2Fs), p53/p21/Hippo pathway25,26,27,28,29.

The physiological function of polyploid hepatocytes has attracted many researchers’ attention. Multiple researches have reported the protective role of polyploid hepatocytes in DEN-induced tumorigenesis using E2F7−/−E2F8−/− mice model with diploid hepatocytes and Anillin−/− mice model with polyploid hepatocytes15,16,30. Guo et al. traced copy number alteration in HCC cells and suggested diploid cell origin of HCC31. Richter et al. also reported reduced nuclear size in preneoplastic cells, suggesting reduced genomic content before carcinogenesis32. These findings suggested that the redundant chromosomes in polyploid hepatocytes are crucial for preventing tumorigenesis induced by various challenges affecting the liver during detoxication15.

Since the ploidy reduction can be found in preneoplastic lesions, we wondered if the ploidy reduction in paracancerous tissues also shows the pathological changes in the liver that support micro satellitosis. We used the number of nuclear in hepatocytes as an indicator for 2 × 2n polyploid hepatocytes, which account for 72% of polyploid hepatocytes in healthy liver13. In our previous research, we manually counted ABH in paracancerous tissues using HE-stained samples and found the attenuation of ABH to be an indicator of HCC short-term recurrence20.

In this article, we tested the performance of our script in assessing ABH and the consistency of cABH with pABH. Our findings demonstrated that using our script for ImageJ software can correctly measure ABH in paracancerous tissues. Computer-assisted assessing of ABH can reduce the inconsistency in manual counting as well as improve efficiency. Based on these results, we proposed our script as an alternative solution for indicating the proportion change of polyploid hepatocytes.

Although we had reported the reduction of ABH in paracancerous tissues of HCC patients compared with patients without tumor diseases, little was known about ploidy changes in other liver cancers20. We are the first to find out that paracancerous ABH of patients with other liver malignancies is also slightly reduced compared with patients with benign disease. This result supports our hypothesis that the microenvironment changes in liver tissue provide supportive ‘soil’ for metastasis in liver. It is worth noticing that paracancerous ABH in HCC is lower not only than those of benign diseases but also ABH in non-HCC malignancies, suggesting tissue background of reduced ABH during original carcinogenesis.

After the discovery of ABH changes in different diseases, we were determined to find the possible relation between ABH and tumor recurrence in HCC patients. We confirmed that ABH was significantly reduced in HCC patients who experienced short-term recurrence. Interestingly, we also established a relationship between ABH attenuation and liver cirrhosis in HCC patients. Cirrhosis is well-known to be the most dangerous risk factor for HCC33. However, the underlying mechanism between cirrhosis and HCC occurrence is yet to be discussed. The relationship between ABH reduction and cirrhosis may be a novel link for that gap.

During liver regeneration, polyploid hepatocytes can give rise to diploid offspring, resulting in higher capacity in proliferation with little chromosome missegregation that are commonly found in tumor cells during ploidy reduction34. However, chronic injury can cause aberrant regulation of hepatocyte ploidy. In DEN induced chronic liver injury mice model, ploidy of hepatocytes initially increases noticeably after 2–3 months, then starts producing atypical cells with reduced ploidy32. In chronic liver injury, DDR pathways are induced in hepatocytes, which leads to activation of DNA damage checkpoint and G2/M arrest, resulting in mononuclear hyperpolyploid hepatocytes when such cells reenter cell cycle35. We believe the iterative challenges in cirrhosis liver have exhausted the regulating mechanisms in hepatocytes, resulting in more rapid attenuation of ABH in paracancerous settings.

Although hepatocytes with reduced ploidy and impaired DDR mechanisms may increase the risk of HCC occurrence in patients with liver cirrhosis, it doesn’t provide further insight of the impact of ABH reduction in paracancerous tissues. In our research settings, most recurrences of HCC within 2 years were more likely due to residual tumor cells, rather than new lesions arising from atypical hepatocytes9. Currently there’s little research discussing the effect of hepatocytes in HCC microenvironment. Anatskaya et al. have reported that polyploid hepatocytes exhibit fundamental metabolism differences from diploid cells36, which could impact the development of residual HCC cells after surgery.

To test if ABH reduction is related with metabolism shift, we analyzed ARG1 expression in paracancerous liver tissues. The suppression of the urea cycle was reported before by Dirk’s team and was considered as one of the tumorigenic promoting metabolism changes37. In their research, a key event in HCC oncogenesis is the downregulation of ARG1 expression to reduce the consumption of arginine. Overexpression of arginine was reported to reduce glycolysis and enhance nucleotide synthesis38. Coincidently, the stimulation of glycolysis is also a feature of polyploid hepatocytes36. This aligns with the observation that polyploid hepatocytes are also characterized by stimulated glycolysis. We hypothesized that the reduction in ARG1 was compensating for the increasing number of diploid hepatocytes. In our study, ARG1 predicted worse OS in BCLC C-stage HCC patients but not in earlier stages. This could be a reflection of the decompensation of the liver repairing system in late-stage HCC patients. However, research concerning the ploidy regulation and metabolism changes of liver cells in tumor settings remains scarce.

It is also worth mentioning that ABH reduction was not significantly related to other clinicopathological features we had tested, especially to AFP, PIVKA-II, HBV, HCV, MVI, and portal thrombosis where little difference was observed. Those features are all biomarkers frequently used today in predicting recurrence39. Although these features provide an invaluable understanding of the tumor’s character, they failed to provide further information about the transformation of the liver tissue. Our findings demonstrated the value of ABH as a novel prognostic factor, as it may bring information on new aspects of disease character into clinical decision-making.

One of the main benefits of choosing ABH to represent the condition of liver tissue is it can be calculated using HE-stained pathology samples of paracancerous tissues, which is routinely produced during pathological diagnosis. Combined with the computer-assisted method of assessing ABH we have described, ABH is highly available in clinical practice. This gives ABH-based prognostic tools a high potential to be publicized. So, we were determined to design a diagnostic model using logistic regression.

Our models of both pABH and cABH showed excellent efficiency in predicting the short-term recurrence of HCC and proved ABH and AFP to be independent risk factors for HCC recurrence. While AFP has long been used for HCC diagnosis, surveillance, and prognosis40,41, its efficiency in predicting recurrence has been doubted by many researchers42. However, our results showed an incredible performance increase when combining AFP with ABH in logistic regression.

Lastly, since our goal is to improve patient selection for adjuvant therapy, we further tested if ABH can identify high recurrent risk HCC patients from those who weren’t recommended adjuvant therapy in real-world treatment decisions. Interestingly, both pABH and cABH are able to distinguish a large proportion of short-term recurrent patients in no adjuvant therapy group. It is worth mentioning that the prognostic effectiveness of ABH is relatively consistent between the adjuvant and the no adjuvant group, demonstrating the independence of ABH from current prognostic tools. These results suggested high potential benefits for high recurrence risk patients if ABH were considered during deciding treatment strategies.

Conclusion

We proposed a computer-assisted method for assessing ABH in paracancerous liver tissue of HCC patients that yields results similar to those counted by pathologists. ABH was found to be an independent risk factor for short-term recurrence after radical surgery, along with preoperative AFP. Our results promote ABH as a novel prognostic factor that may aid in patient selection for adjuvant therapies.

Method

Specimens and clinical data

During 2021 and 2022, pathological samples of 73 patients who underwent liver surgery in the Department of General Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine were enrolled. Of them, 53 were HCC patients, 5 had benign disease, and 15 patients had other malignancies were collected as controls. All patients were PS 0 and Child A before surgery. Clinical data including gender, age, preoperational AFP level, protein induced by PIVKA-II level, etc. were acquired. Patients with malignant disease were followed yearly for recurrence. HE-stained pathological samples of paracancerous tissues or normal tissues for patients with benign disease were provided by the hospital’s pathological department. Informed consent was obtained before enrollment from every patient. The Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine has approved this research. Declaration of Helsinki was applied throughout the research.

Assessing the abundance of binuclear hepatocytes

Each HE-stained sample was independently reviewed by two experienced pathologists as we described previously20. The samples were viewed under x40 microscopes and the field with the highest hepatocyte density was captured for further analysis. To determine pABH, each pathologist individually counted the total number of hepatocytes and binuclear hepatocytes within the field before averaging their results. In cases where the results from two pathologists differ by greater than 20%, a discussion between the pathologists was arranged to determine the proper number. The patients’ outcomes and diseases were blinded to the pathologists during the review.

Another pathologist individually assessed the field with the assistance of a script we wrote for ImageJ software (Rasband, WS, ImageJ, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2016). We have published both the script and a detailed guide explaining each parameter on website: https://hepatocyte.23872502485633.workers.dev/. During the assessment, the picture was gray-scaled before Gaussian smoothing and then binarized for final analysis (Fig. 1A–C). The pathologist selected the appropriate threshold for the size and circularity of the hepatocyte nucleus to exclude inflammatory cells, epithelial cells, and other contaminants. The program then automatically marked and reported the number of hepatocyte nucleus and binuclear cells (Fig. 1D), which was further used to calculate cABH.

Immunohistochemistry assay

53 pairs of IHC stained samples were acquired from the Department of Pathology, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, which were made as a diagnostic procedure after the surgery. The IHC assay were conducted as previously described43. Of the applied antibodies in the IHC samples (AFP, ARG1, CD34, CK7, CK8, CK18, CK19, CEA, GS, GPC3, HSP70, MUC-1 and Ki67), we found ARG1 to be particular interesting as it has recently been reported as an indicator for HCC progression37. ARG1 regulates nucleotide synthesis, which is neccessary for the accumulation of nucleic acid in polyploid cells38. The antibodies against ARG1 were purchased from Proteintech, China, and used according to the manufacturer’s suggestion. An ImageJ plugin44 was used to determine the degree of staining (negative, low positive, positive, and high positive) in paracancerous liver tissues chosen by the pathologist. We chose the cytoplasmic method based on the cellular location of ARG1 and followed the developers’ instruction to evaluate its expression.

TCGA dataset

The dataset of 374 HCC tumor samples and 50 normal liver samples were collected from the Cancer Genome Altas (TCGA: https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/), using R language (version 4.4.1, https://www.r-project.org/). Differential gene expression analysis was performed between tumor samples and normal liver samples. Genes with log2(fold-change) higher or lower than ± 1 and p-values lower than 0.05 were deemed as DEGs.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done in GraphPad Prism version 10.2.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, www.graphpad.com). Unpaired Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test, Kaplan–Meier survival test, linear regression and both univariable and multivariable logistic regression were performed. The null hypothesis was rejected at p-value < 0.05. For the Kaplan-Meier survival test, the primary endpoint was defined as tumor recurrence within two years.

Data availability

Data supporting our findings is provided within this manuscript. Further data can be made available by Junqing Wang upon requests.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Overview and countermeasures of cancer burden in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 66(11), 2515–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-022-2240-6 (2023).

Tabrizian, P., Jibara, G., Shrager, B., Schwartz, M. & Roayaie, S. Recurrence of hepatocellular cancer after resection: Patterns, treatments, and prognosis. Ann. Surg. 261(5), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000000710 (2015).

Vasuri, F. et al. Beyond histology: A tissue algorithm predictive of post-surgical recurrence in hepatocellular carcinomas, including TERT promoter mutation. Virchows Arch. 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-024-03791-y (2024).

Suzuki, H., Mishra, S., Paul, S. & Hoshida, Y. Molecular and immune landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma for therapeutic development. J. Liver Cancer 6. https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2024.12.02 (2024).

Xu, X. F. et al. Risk factors, patterns, and outcomes of late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter study from China. JAMA Surg. 1(3), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4334 (2019).

Fujiwara, N., Friedman, S. L., Goossens, N. & Hoshida, Y. Risk factors and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of precision medicine. J. Hepatol. 68(3), 526–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.016 (2018).

Shimoda, M. et al. Risk factors for early recurrence of single lesion hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. World J. Surg. 40(10), 2466–2471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3529-7 (2016).

Centonze, L. et al. From LI-RADS classification to HCC pathology: A retrospective single-Institution analysis of clinico-pathological features affecting oncological outcomes after curative surgery. Diagnostics (Basel) 10(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12010160 (2022).

Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 8(2), 98–101 (1989).

Pandit, S. K. et al. E2F8 is essential for polyploidization in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 14(11), 1181–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2585 (2012).

Matsumoto, T. Implications of polyploidy and ploidy alterations in hepatocytes in liver injuries and cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169409 (2022).

Gramantieri, L. et al. Alteration of DNA ploidy and cell nuclearity in human hepatocellular carcinoma associated with HBV infection. J. Hepatol. 25(6), 848–853. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80288-1 (1996).

Donne, R., Sangouard, F., Celton-Morizur, S. & Desdouets, C. Hepatocyte polyploidy: Driver or gatekeeper of chronic liver diseases. Cancers (Basel) 14(20). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13205151 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. The polyploid state plays a tumor-suppressive role in the liver. Dev. Cell 26(4), 447–459e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2018.01.010 (2018).

Wilkinson, P. D. & Duncan, A. W. Differential roles for diploid and polyploid hepatocytes in acute and chronic liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 41(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1719175 (2021).

Sladky, V. C. et al. PIDDosome-induced p53-dependent ploidy restriction facilitates hepatocarcinogenesis. EMBO Rep. 3(12), e50893. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050893 (2020).

Duncan, A. W. et al. The ploidy conveyor of mature hepatocytes as a source of genetic variation. Nature 7(7316), 707–710. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09414 (2010).

Toyoda, H. Changes to hepatocyte ploidy and binuclearity profiles during human chronic viral hepatitis. Gut 54(2), 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.043893 (2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Attenuation of binuclear hepatocytes in the paracancerous liver tissue is associated with short-term recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma post-radical surgery. Faseb J. 37(11), e23271. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202301219R (2023).

Bou-Nader, M. et al. Polyploidy spectrum: A new marker in HCC classification. Gut 69(2), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318021 (2020).

Reig, M. et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 76(3), 681–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018 (2022).

D’Amico, G. et al. Clinical states of cirrhosis and competing risks. J. Hepatol. 68(3), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.020 (2018).

Celton-Morizur, S., Merlen, G., Couton, D., Margall-Ducos, G. & Desdouets, C. The insulin/Akt pathway controls a specific cell division program that leads to generation of binucleated tetraploid liver cells in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 119(7), 1880–1887. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci38677 (2009).

Chen, Y., Yu, D., Wang, L. & Du, S. Identification of E2F8 as a transcriptional regulator of gluconeogenesis in primary mouse hepatocytes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 84(12), 1529–1536. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0006297919120125 (2019).

Sladky, V. C. et al. E2F-Family members engage the PIDDosome to limit hepatocyte ploidy in liver development and regeneration. Dev. Cell 52(3), 335–349e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.12.016 (2020).

Fava, L. L. et al. The PIDDosome activates p53 in response to supernumerary centrosomes. Genes Dev. 1(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.289728.116 (2017).

Ganem, N. J. et al. Cytokinesis failure triggers hippo tumor suppressor pathway activation. Cell 158(4), 833–848 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.029

Sladky, V. C. et al. Centriole signaling restricts hepatocyte ploidy to maintain liver integrity. Genes Dev. 18(13–14), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.349727.122 (2022).

Sladky, V. C. et al. PIDDosome-induced p53-dependent ploidy restriction facilitates hepatocarcinogenesis. EMBO Rep. 21(12), e50893. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050893 (2020).

Guo, L. et al. Single-cell DNA sequencing reveals punctuated and gradual clonal evolution in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 162(1), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.052 (2022).

Lin, H. et al. Hyperpolyploidization of hepatocyte initiates preneoplastic lesion formation in the liver. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 645 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20572-8

Marrero, J. A. et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the study of Liver diseases. Hepatol 68(2), 723–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29913 (2018).

Matsumoto, T., Wakefield, L., Tarlow, B. D. & Grompe, M. In vivo lineage tracing of polyploid hepatocytes reveals extensive proliferation during liver regeneration. Cell. Stem Cell 2(1), 34–47e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.11.014 (2020).

Gentric, G. et al. Oxidative stress promotes pathologic polyploidization in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 125(3), 981–992. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci73957 (2015).

Anatskaya, O. V. & Vinogradov, A. E. Genome multiplication as adaptation to tissue survival: Evidence from gene expression in mammalian heart and liver. Genomics 89(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.08.014 (2007).

Mossmann, D. et al. Arginine reprograms metabolism in liver cancer via RBM39. Cell 9(23), 5068–5083e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.011 (2023).

Geiger, R. et al. L-Arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell 20(3), 829–842e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.031 (2016).

Wang, M. D. et al. Prothrombin induced by vitamin K Absence-II versus alpha-fetoprotein in detection of both resectable hepatocellular carcinoma and early recurrence after curative liver resection: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 105, 106843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106843 (2022).

Kocheise, L. et al. EpCAM-positive circulating tumor cells and serum AFP levels predict outcome after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20827 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47580-0

Kim, D. Y. et al. Utility of combining PIVKA-II and AFP in the surveillance and monitoring of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific region. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 29(2), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0212 (2023).

Shim, J. H. et al. Is serum alpha-fetoprotein useful for Predicting recurrence and mortality specific to hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy? A test based on propensity scores and competing risks analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19(01), 3687–3696. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2416-1 (2012).

Wang, N. et al. Positive feedback loop of AKR1B10P1/miR-138/SOX4 promotes cell growth in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Am. J. Translational Res. 12(9), 5465–5480 (2020).

Varghese, F., Bukhari, A. B., Malhotra, R. & De, A. IHC profiler: An open source plugin for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples. PLOS ONE 9(5), e96801. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096801 (2014).

Funding

This study was kindly supported by grants from the following: National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172900; No. 82372603), Shanghai Leading Talent Program of Eastern Talent Plan (No. BJJY2024068), Beijing Medical Award Foundation (No. YXJL-2020-0191-0024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that all data were generated in-house and that no paper mill was used. Yifan Zhang and Yiquan Lu contributed equally in the experiments and the writing of this article. Nan Wang helped with data analyzing and revision. Yongjun Chen and Fengjie Hao helped with patient inclusion and clinical data collection. Junqing Wang and Xiaochun Fei should be considered as joint corresponding authors who designed this study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Lu, Y., Wang, N. et al. Paracancerous binuclear hepatocytes assessed by computer program is a novel biomarker for short term recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Sci Rep 15, 9583 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90004-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90004-4