Abstract

Interval prediction requires not only accuracy but also the consideration of interval width and coverage, making model selection complex. However, research rarely addresses this challenge in interval combination forecasting. To address this issue, this study introduces a model selection for interval forecast combination based on the Shapley value (MSIFC–SV). This algorithm calculates Shapley values to measure each model’s marginal contribution and establishes a redundancy criterion on the basis of changes in interval scores. If the removal of a model does not decrease the interval score, it is considered redundant and excluded. The selection process starts with all the models and ranks them by their Shapley values. Models are then assessed for retention or removal according to the redundancy criterion, which continues until all redundant models are excluded. The remaining subset is used to generate interval forecast combinations through interval Bayesian weighting. Empirical analysis of carbon price shows that MSIFC–SV outperforms individual models and derived subsets across metrics such as prediction interval coverage probability (PICP), mean prediction interval width (MPIW), coverage width criterion (CWC), and interval score (IS). Comparisons with benchmark methods further demonstrate the superiority of MSIFC–SV. Furthermore, MSIFC–SV is also successfully extended to the public dataset-housing price dataset, this indicates its universality. In summary, MSIFC–SV provides reliable model selection and delivers high-quality interval forecasts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Combined forecasting is widely recognized as an effective method to increase prediction accuracy. By leveraging the strengths of multiple models, combined forecasts often outperform individual models1,2,3,4,5. However, the success of combined forecasting depends heavily on the quality of the selected models. Not all combined forecasts exceed the performance of individual models, and including redundant models can reduce accuracy6. Therefore, eliminating redundant models is crucial for improving the performance of combined forecasts6,7. Most existing model selection methods focus on point forecasts, utilizing techniques such as the Akaike information criterion (AIC)8, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC)9,10, encompassing tests1,7, dynamic model selection4, two-stage procedures11, Harvey‒Leybourne‒Newbold (HLN) tests2,12, mutual information13, redundancy-removing linear mutual information model selection (RRLS)14, and comprehensive evaluation index (CEI) methods15,16,17,18,19. While these methods have been successful in point forecasting, the inherent uncertainty in predictions makes errors inevitable.

Interval forecasting directly quantifies prediction uncertainty by constructing prediction intervals, providing a range within which future values are likely to fall, thus reducing the risk of prediction failure. Current interval forecasting methods can be broadly categorized into two types: those based on statistical assumptions, such as the delta method20, Bayesian methods21,22, mean-variance estimation (MVE)23,24, bootstrapping25,26, Gaussian processes27, and distribution estimation (DE)28; and those that directly generate prediction intervals, such as quantile regression (QR)29,30,31 and the lower upper bound estimation (LUBE) method32. Although these methods are theoretically sound and widely used, individual forecasting models are often constrained by their assumptions, limiting their ability to capture data complexity fully. In contrast, interval combination models, which integrate the strengths of multiple models, generally offer more accurate predictions.

In recent years, Wu et al. (2021) proposed a method that combines heterogeneous prediction intervals via continuous Young optimal weighted arithmetic averaging (C-YOWA) and geometric (C-YOWG) operators, with the Theil index as the optimization criterion33. Wang et al. (2023) enhanced interval forecast combination by adopting a ‘divide-and-conquer’ approach34. Meira et al. (2021) suggested eliminating underperforming models before applying the AIC for model selection35, whereas Long et al. (2022) developed an interval forecasting strategy based on linear regression36. Although these studies emphasize model diversity, they often overlook redundancy and interactions between models, limiting further improvements in forecast performance. Thus, the key challenge for enhancing interval forecast performance lies in maintaining model diversity while removing redundant models and accounting for their interactions. Furthermore, interval forecasting must balance not only prediction accuracy but also interval width and coverage, which complicates the selection of suitable models for combination. Existing model selection methods are focused primarily on point forecasts and rarely address the selection of models for interval forecasting. Moreover, interval combinations often assign equal weights to models, which may not reflect each model’s actual contribution. Weight allocation significantly impacts the performance of ensemble forecasting, making it crucial to assign weights that fairly represent each model’s contribution to improve the accuracy of interval combination forecasts.

The Shapley value, a concept from cooperative game theory, quantifies each member’s marginal contribution to a coalition, ensuring a fair distribution of benefits37. Chen (2003) was the first to apply the Shapley value in combined forecasting to determine model weights, treating each predictive model as a participant in a cooperative game38. Subsequent studies have further validated the effectiveness of the Shapley value in optimizing weight allocation. By not only quantifying each model’s contribution but also accounting for interactions between models naturally, the Shapley value ensures that the collective contribution of multiple models is greater than or equal to the sum of their individual contributions. Ding et al. (2023)39 applied the Shapley value for single-item model selection in portfolio modeling, demonstrating its validity, superiority, and robustness in this context. However, their approach focuses on point prediction model selection and employs a simple average weighting method, without considering interval-based model selection or performance-driven weighting strategies.

To address the challenges of model selection in interval combination forecasting and enhance prediction accuracy, this paper proposes a model selection for interval forecast combination based on the Shapley value (MSIFC–SV). The method calculates each model’s marginal contribution via interval scores (ISs) and establishes a redundancy criterion. The model selection process starts with all the models included, with Shapley values determining the order of elimination. Models with lower contributions are prioritized for removal until all redundant models are excluded. Inspired by weighting methods used in point forecasting, interval Bayesian weighting (IBSW), inverse CWC weighting (ICWCW), and inverse IS weighting (IISW) are developed to further optimize the weight allocation for the combined models. The final combined prediction is generated via the best-performing method, interval Bayesian weighting. This approach avoids the complexity of evaluating all possible model combinations and significantly improves the efficiency of model selection.

To ensure model diversity, we selected 10 individual interval prediction models from various forecasting frameworks, including QR, LUBE, DE, and bootstrapping. each individual forecast is generated independently. The LUBE method, combined with neural networks, directly generates prediction intervals through dual outputs. QR constructs intervals by estimating specific quantiles of the target variable. DE assumes that the target variable follows a known distribution, generating intervals by estimating distribution parameters. Bootstrapping, a nonparametric resampling method, generates new samples through repeated sampling to estimate the distribution of statistics and build prediction intervals. The effectiveness and robustness of our selection method are validated through empirical analysis of housing and carbon price datasets.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) This provides a new approach to model selection in interval combination forecasting, enhancing prediction accuracy to some extent.

(2) This study innovatively applies the Shapley value from cooperative game theory to model selection in interval combination forecasting. By quantifying each model’s marginal contribution and considering interactions between models, a more rational model selection process is achieved.

(3) A redundancy criterion based on interval score increments is established. By assessing changes in the interval score after removing a model, the effectiveness and precision of model selection are enhanced.

(4) The introduction of IIS, ICWCW, and interval Bayesian weighting methods optimizes the weight allocation in interval ensemble forecasting, further enhancing the reliability and accuracy of the prediction results.

The remaining sections of this paper are as follows. Section "Preliminary knowledge" lists the technologies involved in the proposed MSIFC–SV. The specific framework of the proposed MSIFC–SV is listed in Sect. "Selection procedure for the superior subset". The experimental preparations and two experiments are presented in Sect. "Experiment". Section "Conclusions" concludes our study.

Preliminary knowledge

This section introduces two prevalent predictors, artificial neural networks and long short-term memory networks, along with four single-interval prediction frameworks: lower-upper bound estimation, bootstrap, quantile regression, and distribution estimation, which do not require uncertainty labels. It also defines key evaluation metrics for interval prediction: prediction interval coverage probability, mean prediction interval width, coverage width-based criterion, and interval score.

Predictors

Artificial neural network

An artificial neural network (ANN) is a mathematical model known for its adaptability, self-learning capabilities, and ability to learn in real time. It consists of a vast network of interconnected neurons that process information distributively. Typically, an ANN includes three parts: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, as shown in Fig. 1. The ANN creates a nonlinear mapping between input and output samples by leveraging the self-learning capability of its neurons. Each layer of the network consists of multiple nodes connected by weights across layers. Upon receiving an input signal, a neuron applies an activation function to perform a nonlinear transformation of the signal before forwarding it to the next layer. Initially, weights are set randomly but are adjusted continuously during training to align the neuron outputs with a predefined target, thereby iteratively refining the network’s accuracy in mapping inputs to outputs.

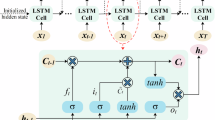

Long short-term memory

First introduced by Hochreiter & Schmidhuber (1997)40, the LSTM network is an advanced variant of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) designed to address issues such as ‘gradient explosion’ and ‘gradient vanishing’, which are common in traditional RNNs. LSTM, a key deep learning algorithm, excels at analyzing and predicting time series data with long intervals and delays. An LSTM cell consists of four interconnected components: an input gate, an output gate, a forget gate, and a cell state. These components work in concert to enable the LSTM’s time memory function through the toggling of gates. The cell architecture is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The cell state is the central component of the LSTM network, acting as its ‘memory’, which can be selectively retained or discarded through a ‘gate’ mechanism. This allows the network to maintain or forget information as needed. Its operation is governed by the following formula:

where \({i_t}\), \({f_t}\) and \({o_t}\) represent the input, forget, and output gates, respectively, and where \({x_t}\) is the current input. \({W_f}\), \({W_i}\), \({W_c}\) and \({W_o}\) denote the weights corresponding to each gate, whereas \({b_f}\), \({b_i}\), \({b_c}\) and \({b_o}\) are the biases for each state. \({g_t}\) refers to the candidate vector at time t, and \({C_t}\) indicates the cell state at time t. The sigmoid function \(\sigma\) and hyperbolic tangent function tanh are the activation functions used. \({h_t}\) denotes the output of the \(t{\text{-}}th\) cell, and \({h_{t - 1}}\) is the output of the previous cell.

Methodology of interval forecasting

Interval forecasting

The principle of regression involves the use of a data generation function, denoted as \(f( \cdot )\), in combination with additional noise to model the observable target values \({y_i}\).

where \({x_{i - 1}}=[{x_{1(i - 1)}},{x_{2(i - 1)}}, \cdots ,{x_{m(i - 1)}}]\) and where m represents the number of independent variables. For \({x_i}\) and \({y_i}\), \(i=1,2, \cdots ,n\). \({\sigma _{noise}}\) is referred to as irreducible noise or data noise, which may arise from explanatory variables that are not observed within x or from inherently stochastic processes in the data.

The size of a minibatch is n, and \({x_{i - 1}}\) is the \(i{\text{-}}th\) input of \({y_i}\). The concept of uncertainty quantification is to forecast intervals \([\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{L},\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{U}]\)such that \({y_i}\) satisfies the following:

where \(\Pr [y_{{_{i}}}^{L} \leqslant {y_i} \leqslant y_{{_{i}}}^{U}]\) represents the PI coverage probability (PICP) and where \({P_c}\) denotes the preset confidence level. The PICP is a measurement correlated with the credibility of the created PI and is represented as:

where \({c_i}=1\) if \({y_i}\) is within the interval \([\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{L},\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{U}]\); otherwise, \({c_i}=0\). Note that a PI is meaningless if \(\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{L}\) is extremely small and if \(\hat {y}_{{_{i}}}^{U}\) is excessively large. The ideal PI should be as narrow as possible while satisfying Eq. (8)41.

MPIW denotes the mean PI width23,42,43,44, which is defined as:

Lower upper bound estimation (LUBE)

In41, the loss function of the uncertainty-based PI (UBPI) was defined with two terms:

where \({L_{MPIW}}\) represents the loss of the PI width and point estimate and where \({L_{PI}}\) denotes the loss of the PI coverage probability. \({\lambda _1}\) is the hyperparameter that determines the relative importance of two terms.

\({L_{MPIW}}\) is obtained by estimating the uncertainty in the regression task42,45. \({L_{MPIW}}\) is defined as follows:

where MSE represents the mean squared error of a minibatch, and44 employs the midpoint of the interval as the point estimation.

Studies42,43 inspired the development of \({L_{PI}}\), which is developed as follows to learn the PI:

The Boolean values of \({c_i}\) in Eq. (9) result in a nondifferentiable \({L_{PI}}\) loss in the backpropagation algorithm because of the max operation in Eq. (15). It is therefore replaced with a softened version, as follows32,44,46,47:

where \({f_{sigmoid}}\) is the sigmoid activation function and where \(s>0\) is the hyperparameter factor of softening.

Thus, the loss function of interval prediction proposed by41 can be defined as:

where n is the number of predicted \({y_i}\). \({\lambda _1}\) balances the importance between the PICP and MPIW.

Salem et al. (2020)43 proposed an effective method. Their loss function is defined as follows:

where \(\xi\) is a preset value, and with reference to previous studies, we take \(\xi\)= 10.

The flow chart for generating prediction intervals based on the LUBE framework with ANN and LSTM predictors is shown in Fig. 3.

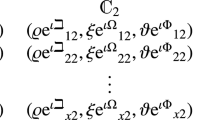

Quantile regression (QR)

Regression analysis essentially minimizes the mean square error to estimate the conditional expectation of a dependent variable given independent variables. Quantile regression is the integration of the concept of quantiles into ordinary linear regression. It can predict any conditional quantile of the target variable and is not restricted to forecasting only the mean. The definition of a loss in QR is

where \({\xi _i}={y_i} - f({x_{i - 1}})\), \(\alpha\) is the desired quantile. \({y_i}\) is the target value for the corresponding input \({x_{i - 1}}\), and \(f( \cdot )\) is the quantile regression function.

The PI is constructed by integrating the QR loss function into ANN and LSTM models. Two separate models with various quantiles are trained, one for the upper bound (\({\alpha _u}\)) and the other for the lower bound (\({\alpha _l}\)). For example, to create a PI with a 95% confidence level, we apply the 97.5% and 2.5% quantiles in the QR loss function. This method circumvents issues such as model complexity, the need for prior distribution assumptions, and biased parameter estimation errors often encountered in traditional interval predictions. The structure is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Bootstrap

The bootstrap method is a statistical technique that involves repeated sampling from the original sample and is also known as the self-help method. It does not require prior assumptions about sample distribution48. Bootstrapping is an effective method for estimating machine learning uncertainty. It obtains L sets of training samples by randomly sampling the original data with replacement and trains L learning models separately to construct the model estimation error variance \(\sigma _{i}^{2}({x_{i - 1}})\), which can represent model uncertainty caused by human factors such as model structure and parameter settings49. On the basis of the obtained \(\sigma _{i}^{2}({x_{i - 1}})\) and \(\varepsilon ({x_{i - 1}})\), a prediction interval with a confidence level \((1 - \alpha )\%\) is constructed:

where \({Z_{_{{1 - \frac{\alpha }{2}}}}}\) is the \(1 - \frac{\alpha }{2}\) quantile of the standard normal distribution.

The structure of the bootstrap-ANN and bootstrap-LSTM is shown in Fig. 5, with the following steps:

(1) Data preprocessing. The samples are normalized to the interval [0, 1].

(2) Bootstrap resampling. The original training set \(D=\left\{ {({x_{i - 1}},{y_i})} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{n}\) is sampled L times with replacement to create L training sample sets \(\left\{ {({x_{i - 1}}^{l},{y_i}^{l})} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{n},l=1,2, \cdots L\).

(3) The first bootstrap sample \(\left\{ {({x_{i - 1}}^{1},{y_i}^{1})} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{n}\) is used to train the ANN and LSTM and to obtain the predicted values \({\hat {y}_1}(x_{{i - 1}}^{1})\).

(4) The above steps are repeated L times to obtain L predicted values\(({\hat {y}_1}(x_{{i - 1}}^{1}),{\hat {y}_2}(x_{{i - 1}}^{2}), \cdots ,{\hat {y}_L}(x_{{i - 1}}^{L}))\) and the model error variance \(\sigma _{i}^{2}\).

(5) The mean of the predicted values \(\bar {\hat {y}}({x_{i - 1}})\) of the ANNs and LSTMs is obtained from the above steps, and the model error variance \(\sigma _{i}^{2}\) is used to construct a new training sample \(D{}_{{new}}\).

(6) Similar to Steps (2)-(5), L draws from the training sample \(D{}_{{new}}\) are used to train ANNs and LSTMs to obtain the data noise error variance \(\sigma _{\varepsilon }^{2}\).

(7) The prediction interval is obtained from \(\bar {\hat {y}}({x_{i - 1}})\), \(\sigma _{i}^{2}\), and \(\sigma _{s}^{2}\).

Distribution estimator (DE)

The interval prediction method using distribution estimators was proposed by Saeed et al. (2022)28. DE can predict the distribution of predictions without any retraining. The core concept involves training a system to predict two values: the forecast value and an estimation of the error of the forecast value. It is assumed that potential predictions follow a normal distribution. Hence, the distribution estimator considers the forecast as the mean and uses the forecast error as an approximation of the distribution’s standard deviation. The distribution is estimated as a Gaussian function centered on the forecast, with its standard deviation equal to the estimation error. DE then uses these estimates and estimation errors to generate prediction intervals.

To obtain the prediction values and prediction errors, DE employs a two-step system, as shown in Fig. 6. The first step trains the model on the training dataset to generate the predictions for the test set. The first-step model is referred to as the base model. The loss function for model training is the MSE, which is defined as:

where \({\hat {y}_i}\) is the predicted value of the base model and where \({y_i}\) is the observation value.

The second step is to predict the variance, and the model used in this step is known as the error model. The model uses the test data as input, and the predicted label is the square of the difference between the predicted value of the first step and the actual value. The structure of the second step model is similar to that of the base model, with the loss function being defined as

where \(\hat {\varepsilon }_{i}^{2}\) denotes the value predicted from the error model. By utilizing the outputs from both the base and error models, prediction intervals can be generated with the distribution estimator. These intervals are constructed according to Eqs. (23) and (24).

where \(\hat {y}_{i}^{L}\) and \(\hat {y}_{i}^{U}\) denote the lower and upper bounds of the PI at \(i - th\), respectively. B denotes the error range, which is defined by

where s is an unbiased estimate of \(\sigma\). s is defined by Eq. (26)28,48.

where \({Z_{\frac{\alpha }{2}}}\) is a standard normal variable with a cumulative probability level of \(\frac{\alpha }{2}\).

The constructed ANNDE and LSTMDE are able to estimate any quantile of the target without the need for retraining. The process is shown in Fig. 6.

Evaluation metrics for the PI

We evaluate the quality of the PI in terms of the PICP, MPIW, CWC and IS. The PICP and MPIW are defined as shown in Eqs. (9) and (10) above, respectively. The CWC and IS are defined as follows.

The PI normalized average width (PINAW) is designed as follows:

The CWC, which combines the coverage and width of the PI, is defined as follows:

where \(R=\mathop {\hbox{max} }\limits_{{1 \leqslant i \leqslant n}} ({y_i}) - \mathop {\hbox{min} }\limits_{{1 \leqslant i \leqslant n}} ({y_i})\) is the range of the predicted target and where \(\eta\) is the penalty coefficient used to penalize the case when the PICP is smaller than \({P_c}\). If the PICP is smaller than \({P_c}\), the prediction applies an exponential penalty to \(\gamma (PICP)\) to minimize the gap between the PICP and \({P_c}\). The primary focus is on the PINAW when the PICP is greater than or equal to \({P_c}\).

The interval score (also known as the Winkler score)50,51 is a scoring mechanism used to evaluate the quality of prediction intervals. It not only accounts for the interval width, which is defined as \(\hat {y}_{i}^{U} - \hat {y}_{i}^{L}\), but also imposes penalties when the actual value \({y_i}\) falls outside the interval. The interval score is defined as follows:

where \(I{S_i}\) is the interval score at time i. In particular, IS represents the final interval score. The score encourages intervals that are narrow yet contain the actual value and penalizes cases where the actual value lies outside the predicted interval.

The PICP reflects the reliability of the PI, indicating the probability that the predicted target falls into the PI. The larger the PICP is, the more reliable the interval. The MPIW measures the accuracy of the PI, and a smaller MPIW indicates greater accuracy. When the PICP exceeds Pc, attention should focus on the width of the PI. Specifically, when the PICP is above Pc, a smaller MPIW is preferred. The CWC is an evaluation metric that considers both the PI’s coverage and width; a lower CWC signifies a higher quality of the PI. A lower IS indicates a more accurate and reliable prediction interval.

Selection procedure for the superior subset

Combined interval prediction

Combined interval forecasting is a method that uses specific mathematical models or algorithms to integrate multiple independent interval forecasts into a prediction by assigning specified weights. Assuming that there are k individual interval predictions, with \({\hat {f}_k}\) representing the prediction interval for the \(k{\text{-}}th\) individual forecast, the combined interval forecast can be formulated as follows:

where \({\hat {f}_c}\) represents the prediction interval of the combined model and where \({w_k}\) denotes the weight assigned to the \(k{\text{-}}th\) individual interval prediction within the combined model. \({w_k}\) takes values in the range of [0, 1], and \(\mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^K {w_k} = 1\).

We assume that \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) is the prediction interval for the \(k{\text{-}}th\) forecast and that \(\hat {y}_{{kt}}^{L},\hat {y}_{{kt}}^{U}\) are the lower and upper bounds of the prediction interval for the \(k{\text{-}}th\) forecast at time t, respectively.

This study introduces an interval Bayesian weighting (IBSW) algorithm based on Bayes’ theorem52. It calculates the posterior probability of each model by evaluating the relationship between the predicted intervals and observed values. The posterior probabilities are then used as weights to combine the models’ predictions.

Assuming that each model has an equal prior probability, the prior probability can be defined as:

For each model, the likelihood function is defined on the basis of the predicted interval bounds \([\hat {y}_{i}^{L},\hat {y}_{i}^{U}]\) and the observed value \({y_i}\):

This function represents the probability of the observed value \({y_i}\) falling within the predicted interval \([\hat {y}_{i}^{L},\hat {y}_{i}^{U}]\).

According to Bayes’ theorem, the posterior probability of the model is calculated as follows:

where, \(\sum\nolimits_{{l=1}}^{K} {P({y_i}|{M_{tl}})P({M_{tl}})}\) is the sum of the product of likelihoods and prior probabilities across all models, serving as a normalization factor.

Unlike point forecasting, interval forecasting must account for both interval width and coverage, which often conflict with each other. Evaluating interval forecasts on the basis of only one of these metrics is incomplete. CWC and IS are comprehensive metrics that consider both width and coverage. Inspired by the inverse variance weighting method used in point forecasting, this study proposes a new weighting algorithm based on the reciprocals of CWC and IS.

Assume that \(CW{C_k}\) and \(I{S_k}\) represent the CWC and IS of the \(k{\text{-}}th\) interval prediction, respectively, which are defined as follows:

where \(\gamma (PIC{P_k})=\left\{ \begin{gathered} 0,{\text{ }}PIC{P_k} \geqslant {P_c} \hfill \\ 1,{\text{ }}PIC{P_k}<{P_c} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.\).

After individual forecasts are obtained, we can combine these models via various methods to obtain a more comprehensive reflection of the quality of the prediction intervals. The weighting method is defined as follows:

Definition 1

ISc represents the combined IS

We assume that \(F=\left\{ {{{\hat {f}}_1},{{\hat {f}}_2}, \cdots ,{{\hat {f}}_K}} \right\}\) represents a combination of k single-interval predictions. \(I{S_c}(F)\) denotes the IS of F, which is defined as follows:

We define \(\Delta IS\) as the increment of the \(IS\), and \(\Delta I{S_c}(F,F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} )\) represents the increment of the combination F containing the model \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) compared with the combination F not containing \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\). If

then \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) is a redundant forecast in the combination.

Definition 2

We assume that \(F=\left\{ {{{\hat {f}}_1},{{\hat {f}}_2}, \cdots ,{{\hat {f}}_K}} \right\}\) is a combination of k interval forecasts and that \(S \subseteq F\). S is considered the superior subgroup within the combination F if it satisfies the following two conditions:

Shapley values for interval prediction combinations

By quantifying each model’s contribution and accounting for interactions between models, the Shapley value ensures that the combined contribution of multiple models is greater than or equal to the sum of their individual contributions. We apply Shapley value theory to model selection in interval forecast combinations, which we refer to as MSIFC-SV. Instead of profitability, the IS is used to calculate Shapley values for each interval forecast in the coalition. Because IS is the comprehensive metric that balances interval width and coverage, which are often conflicting criteria in interval forecasting. By using the opposite of IS, the Shapley values more accurately capture the overall performance of each interval forecast. The order in which individual interval predictions enter the selection process is determined by their Shapley values. Predictions are then evaluated sequentially to determine whether they are redundant without considering all possible combinations, thus improving the efficiency of the selection process.

Definition 3

We suppose that \(M=\left\{ {1,2, \cdots ,K} \right\}\) is a coalition consisting of K participants. For any subset \(S \subseteq M\), if there is a corresponding real-valued function \(v(S):{2^M} \to R\) that satisfies \(v(\phi )=0\), then \(v(S)\) is said to be the characteristic function, representing the payoff to subset S of M when acting in unison. K denotes the number of participants.

\(v(S)\) has superadditivity, that is,

Definition 4

We assume that \(F=\left\{ {{{\hat {f}}_1},{{\hat {f}}_2}, \cdots ,{{\hat {f}}_K}} \right\}\) is a combination of K individual interval predictions. For any subset \(S \subset F\),

where \({v_f}(S)\) represents the opposite of the IS of set S and where \({\Gamma _f}=[F,{v_f}]\) is defined as the cooperative game of K individual interval predictions; then,

According to Eq. (49), we have

Definition 5

A cooperative game \(\Gamma =[M,v]\) is given, and its Shapley values can be described as:

where

In Eq. (54), \(v(S \cup \{ k\} ) - v(S)\) is the marginal contribution of the \(k{\text{-}}th\) participant when added to the coalition S in the cooperative game. The Shapley value is described as the weighted average of the marginal contributions of the \(k{\text{-}}th\) participant in the cooperative game.

Since \({\Gamma _f}=[F,{v_f}]\) is regarded as a cooperative game with K participants, we present the following Corollary 1 from Definition 5.

Corollary 1

If \({\Gamma _f}=[F,{v_f}]\) defines a cooperative game defined by interval forecasting combinations, \(F=\left\{ {{{\hat {f}}_1},{{\hat {f}}_2}, \cdots ,{{\hat {f}}_K}} \right\}\) represents a combination of K individual interval predictions, and the Shapley value is given by

where S is a subset of \(F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) and s=|S| is the number of the set S.

The incremental IS of adding an interval prediction \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) to coalition S can be expressed as

If \({\varphi _k}({v_f}) \leqslant {\varphi _j}({v_f})\), according to Eq. (46), we have

Equation (57) shows that a prediction with a larger Shapley value has a smaller IS increment when it is added to the coalition by weighting the inverse of the IS.

On the basis of the above, we obtain the following inference:

(1) \(I{S_k}\) is used to measure the quality of the prediction intervals for \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\), with smaller values of \(I{S_k}\) causing a larger \({\varphi _k}({v_f})\).

(2) \(I{S_c}(F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} )\) reflects the quality of the prediction intervals for coalition \(F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\), and as \(I{S_c}(F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} )\) decreases, \({\varphi _k}({v_f})\) increases.

(3) \(I{S_c}(F,F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} )\) describes the IS between the combinations F and \(F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\). As \(I{S_c}(F,F - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} )\) increases, \({\varphi _k}({v_f})\) decreases.

Model selection for interval prediction combination based on shapley value

In this section, the MSIFC-SV algorithm is used to identify the superior subset from a set of interval forecasts. Initially, all the K interval predictions are included in the superior combination. During the selection procedure, the order in which individual interval predictions are evaluated is determined by their Shapley values. The algorithm iteratively eliminates redundant models in a loop until all redundant models have been eliminated.

The specific steps of the selection algorithm based on the Shapley value are as follows:

Step 1

Input the prediction intervals and the actual observed values for all individual forecasts.

Step 2

Compute the IS for each forecast via Eqs. (30) and (31).

Step 3

Initialize the superior combination set to include all individual forecasts.

Step 4

Define the prediction coalition \({F_0}\) as containing \({n_0}\) interval forecasts. For any \(S \subseteq {F_0}\), let \({v_f}(S)= - I{S_c}(S)\). \({\Gamma _0}=[{F_0},{v_f}]\) is a cooperative game comprising \({n_0}\) individual interval forecasts in \({F_0}\).

Step 5

For \({n_0}\) interval forecasts within \({\Gamma _0}\), the Shapley values \({\varphi _k}({v_f})\), where \(k=1,2, \cdots ,{n_0}\), of the different prediction coalitions can be calculated via Eq. (55). Let \(V=\left\{ {{\varphi _1}({v_f}),{\varphi _2}({v_f}), \cdots ,{\varphi _{{n_0}}}({v_f})} \right\}\) be the set of Shapley values.

Step 6

The minimum value in V is denoted by MinV, and the size of V is defined as \(\left| V \right|\).

Step 7

Determine whether the interval forecast \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) corresponding to MinV is considered redundant in accordance with Definition 1.

If \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) is determined to be a redundant model, then it is removed from the coalition \({F_0}\). Subsequently, Steps 4–7 are repeated for the new coalition \({F_0}={F_0} - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\).

If \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) is not a redundant model and \(\left| V \right|>1\), then let \(\left| V \right| - \left\{ {\hbox{min} V} \right\}\) and repeat Steps 6–7.

If \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\}\) is not a redundant model and \(\left| V \right|=1\), then there is no redundant model in \({F_0}\); thus, \({F_0}\) is the superior subgroup.

According to the criterion for determining redundant forecasts established in Definition 1, there is no redundant model in \({F_0}\). Therefore, for any \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\} \in {F_0}\), we have

In contrast, \(F - {F_0}\) comprises all redundant models within \({F_0}\). For any \(\{ {\hat {f}_k}\} \in F - {F_0}\), we have

Equations (49) and (50) are combined to yield:

1. \(I{S_c}({F_0})<I{S_c}({F_0} - \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} ),\forall \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} \in {F_0},\)

2. \(I{S_c}({F_0}) \leqslant I{S_c}({F_0} \cup \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} ),\forall \{ {\hat {f}_k}\} \in F - {F_0}.\)

On the basis of Definition 2, we can conclude that \({F_0}\) is the superior subgroup.

The process of selecting the superior subgroup on the basis of the Shapley value is shown in Fig. 7 and Algorithm 1, and the interval forecast flow of the superior subgroup is shown in Fig. 8.

Experiment

To assess the effectiveness, superiority, and robustness of the MSIFC–SV algorithm, two experiments are conducted. Each experiment generated ten individual interval forecasts, employing ANN and LSTM predictors within the LUBE, QR, bootstrap, and DE frameworks. To reduce the randomness inherent in neural networks, the experimental results represent the averages of 15 repetitions. In Experiment 1, the MSIFC–SV selection method is applied to assess the algorithm’s effectiveness by forecasting daily average prices of the Hubei carbon emission trading market in China from January 3, 2017, to February 28, 2022 (data from http://www.tanpaifang.com/). The performance of the subsets selected by the proposed algorithm is compared with their derivative subsets and the best individual interval predictions via the PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS metrics. Additionally, these subsets are compared with those from other selection methods. In Experiment 2, Boston housing price data from the Statistical Data Sets at Carnegie Mellon University (https://lib.stat.cmu.edu/datasets/boston) are used to verify the algorithm’s superiority and robustness. The methodologies for Experiment 2 are consistent with those of Experiment 1.

In Experiment 1, following the methodology outlined by Xie et al. (2022)53, 15 variables from diverse domains, including macroeconomics, international carbon markets, energy prices, climate and environment, and public concerns, were preliminarily selected. All these variables are considered potential influencers of carbon price. To increase the forecasting efficiency, we employed LassoCV for feature selection, as it is known for effectively identifying key features in high-dimensional data54. The results of the feature selection for all the experiments are presented in Table 1. During the experiment, the data are divided into training and testing sets, with the specific split detailed in Table 2. Model parameters are set on the basis of referenced studies and specific experimental requirements, as detailed in the Supplementary Table 1.

Experiment 1

Table 3 presents the PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS for various individual interval predictions. The results show that SNM–ANN outperforms all the other methods, achieving a PICP of 0.9835, an MPIW of 10.7694, a CWC of 0.2834, and an IS of 10.8786. Notably, SNM–ANN achieves the smallest CWC and MPIW values among all the models when the PICP exceeds Pc. This finding indicates that SNM–ANN provides a narrower prediction interval while ensuring satisfactory coverage, thereby delivering higher-quality prediction intervals. In contrast, QR-LSTM performed the worst, with coverage significantly below the target Pc, indicating low prediction reliability. Among the individual predictions, only SNM–ANN, SNM-LSTM, and ANNDE achieved interval coverage at the predefined confidence level.

Table 4 presents the results of the PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS for all individual combinations and the best individual prediction under different weighting methods. The simple average (SA) weighting method computes the mean of the upper and lower bounds of multiple forecast intervals to generate an interval combination prediction. In contrast, the median weighting method selects the median55 of the upper and lower bounds across forecast intervals to form the interval combination prediction. The results indicate that all combinations achieve a PICP above the set threshold (Pc). However, only the weighted combinations via IBSW and IISW outperform the best individual prediction in terms of the MPIW, with values of 10.7455 and 10.6458, respectively, both lower than the optimal individual model’s MPIW of 10.7694. Additionally, the weighted combination via IBSW achieves the lowest CWC and IS values of 0.2661 and 10.7455, respectively, compared with the optimal single model’s values of 0.2834 and 10.8786, respectively. This finding indicates that including all the individual models may introduce redundancy, leading to decreased prediction performance and further highlights the importance of careful model selection.

Moreover, the significant differences in performance across various weighting methods underscore the need for careful allocation of prediction weights in ensemble models. Given that the weighted combination using IBSW achieves the smallest CWC and IS values, the IBS method is used to construct the ensemble in subsequent experiments.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the MSIFC–SV algorithm, we compared the superior subset selected with the best individual prediction and further analyzed the performance changes when adding or removing a model from the superior subset. As shown in Table 5, the subset selected on the basis of Shapley values significantly outperforms its derived subsets and the best individual prediction across the PICP, MPIW, CWC, and WS metrics. The superior subset {5,6} achieved PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS values of 1, 5.4061, 0.1397, and 5.4061, respectively. This subset not only provided 100% coverage but also presented the narrowest interval width among the compared subsets. Compared with the best individual model and all individual model combinations, the interval width of the superior subset is reduced by 49.80% and 49.69%, respectively. Removing any model from the optimal subset resulted in coverage falling below the confidence level, whereas adding any model achieved 100% coverage but with a width between 6 and 8. These results demonstrate that the proposed selection algorithm effectively identifies a superior subset.

To further validate the effectiveness of the MSIFC–SV algorithm, we compared it with existing point prediction model selection methods (e.g., the HLN test2, encompassing test7, CEI18, MI13, and RRLS14), as there are no established methods for interval prediction model selection. We used the midpoints of all the individual prediction intervals and the true values as inputs to apply these point prediction model selection algorithms. We subsequently combine the selected intervals into an interval prediction via the interval Bayesian weighting algorithm. The comparison results are presented in Table 6; Fig. 9.

Across all combinations, every subset’s PICP exceeded the threshold Pc, with the subset selected by the MSIFC–SV algorithm demonstrating superior performance. The subset identified by the CEI method matched the subset chosen by the MSIFC–SV algorithm, whereas the HLN method performed the worst. The MI and RRLS methods, both of which are based on mutual information, performed well but were still outperformed by our proposed method. Notably, the subset selected by the RRLS method did not achieve the minimum MPIW but yielded the smallest CWC and the largest IS. This discrepancy highlights limitations in existing comprehensive evaluation metrics for interval prediction, such as CWC and IS. Future work will focus on identifying more suitable evaluation metrics.

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, a Wilcoxon test is conducted to compare the prediction intervals of the superior subsets selected by the proposed algorithm with those selected by the baseline algorithm. Since the Wilcoxon test is based on point differences, this study revises the calculation to better account for the differences between the bounds of intervals. For n pairs of data \(({x_i},{y_i})~\), where i = 1,2,…,n, the difference for each pair is calculated as:

\({d_i}={x_i} - {y_i}.~\)

In the case of interval data, the revised calculation is applied to n pairs of interval data \(([x_{i}^{L},x_{i}^{U}],[y_{i}^{L},y_{i}^{U}]).\) The difference is now expressed as:

.

All remaining steps and the theoretical framework of the method remain consistent with the original approach.

The significance level is set at 0.1, where a p value less than 0.1 indicates a significant difference between the two methods. Since the CEI method selects the same subset as the proposed algorithm does in this example, it is not included in this test. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7 shows that the proposed algorithm significantly differs from HLN (0.05)2, the encompassing test7, MI13, and RRLS14. Although the differences with HLN (0.15, 0.25) and HLN (0.35) are not statistically significant, the analysis indicates that, while maintaining confidence levels, the proposed algorithm reduces the width of the prediction intervals by 54.19% and 53.73%, respectively, compared with these two methods.

Experiment 2

Table 8 presents the individual interval prediction results for the Boston housing prices, highlighting significant differences in model performance. The ANNDE model demonstrated the best predictive performance, achieving a PICP of 0.9509, an MPIW of 19.5354, a CWC of 0.3992, and an IS of 23.8322. Notably, the SNM-ANN, bootstrap-ANN, and bootstrap-LSTM models failed to reach the specified confidence level Pc. Among these, the PICP of the bootstrap-based models fell below 0.9, substantially lower than the target of 0.95, indicating a lower predictive reliability in this context. This underscores the limitations of single models in capturing complex information patterns.

To further assess the robustness of the MSIFC–SV algorithm, we conducted a comparative analysis using the Boston housing price dataset from two perspectives. Table 9 presents the results for the optimal individual prediction, various combinations of individual predictions via different weighting methods, the subset selected via the MSIFC–SV algorithm and its derived subsets, and the subsets selected via benchmark selection methods. Figure 10 provides a visual comparison of the various metrics. The subset {5, 6, 7}, selected by the MSIFC–SV algorithm, with PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS values of 1, 16.4609, 0.3116, and 16.4609, respectively, outperforms the optimal individual prediction, all individual model combinations, its derived subsets, and the subsets selected by the benchmark algorithms.

For all combinations of single models using different weighting methods, the coverage rates exceeded the confidence level Pc, but their MPIWs were all greater than 20, even larger than the best-performing individual interval. This finding indicates that redundant models within the combinations limit predictive performance, underscoring the importance of model selection in interval combination forecasting. Among all individual model combinations, the IBSW weighting method achieved the smallest MPIW and IS, with the CWC being the second smallest, highlighting the method’s superiority. However, even when coverage meets the target and the interval width is minimized, the CWC does not reach its lowest value, revealing the limitations of the CWC in providing a comprehensive evaluation of interval predictions.

Removing model {7} from the superior subset results in a coverage rate below Pc, demonstrating that model {7} is essential in the combination. Adding any other model to the superior subset maintains a coverage rate of 100%, but with increased interval width, further highlighting the superiority of the selected subset.

Additionally, in the benchmark selection methods, the coverage rates all exceeded the confidence level, but the interval widths ranged between 18 and 20, which are noticeably larger than those of the subset selected by the MSIFC-SV algorithm. This further emphasizes the robustness of the proposed algorithm, which identifies a superior predictive subset by considering diversity, redundancy, and interdependencies within the combinations.

A Wilcoxon test is also conducted to compare the prediction intervals of the superior subsets selected by the proposed algorithm with those selected by the baseline algorithm in this case. The results are shown in Table 10.

The proposed algorithm shows a significant difference compared with the HLN test2, MI13, and RRLS14. Although the differences between the proposed algorithm and the encompassing test7 and CEI method did not reach a level of significance, as shown in Table 8; Fig. 10, when the PICP exceeds the confidence level, the prediction interval of the proposed algorithm reduces the MPIW, CWC, and IS by 13.17%, 33.23%, and 13.17%, and 15.71%, 38.27%, and 45.69%, respectively, compared with these two methods.

Experiment 3

To evaluate the scalability of the proposed model selection algorithm, we apply it to interval forecasting of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices, with data sourced from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (https://www.eia.gov/). The daily data spans from January 4, 2010, to December 31, 2024. Additionally, to assess the performance of the algorithm as the number of models increases, we conduct model selection experiments using model pools containing 10, 15, and 20 sub-models. Based on the aforementioned interval forecasting framework, this section introduces interval prediction models under both GRU and CNN predictors, including SNM-GRU, UBPI-GRU, bootstrap-GRU, QR-GRU, GRUDE, SNM-CNN, UBPI-CNN, bootstrap-CNN, QR-CNN, and CNNDE. The parameter settings are provided in the Supplementary Table 1. Table 11 presents the forecasting performance of each individual model.

Table 12 compares the subsets of models selected by the proposed method from model pools of 10, 15, and 20 models with those selected by the Encompassing test7, CEI18, MI13, and RRLS14 methods. As shown in the table, the proposed method demonstrates advantages in PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS metrics across all three model pool sizes (10, 15, and 20), confirming its effectiveness and superiority in interval forecasting for WTI, as well as its scalability. Additionally, it is observed that as the number of sub-models in the model pool increases, the performance of the final selected subset from the proposed method improves.

Specifically, the subsets selected by all model selection algorithms achieved the pre-set coverage rate of 0.95. The proposed method consistently maintains the interval width below 9, ensuring both high coverage and narrower intervals. Among the comparison methods, the subsets selected by CEI and RRLS showed better performance. The RRLS method selects fewer sub-models compared to the others, while the Encompassing test tends to select a larger number of sub-models for combination. Notably, the subsets selected by RRLS in both the 15-model and 20-model pools are identical. The performance of MI fluctuates significantly across different model pool sizes.

Conclusions

To address the challenges of model selection in interval combination forecasting, this work introduces a novel algorithm, MSIFC–SV, for selecting models in interval forecasting combinations. This algorithm calculates the marginal contribution of each individual prediction within the combination via the IS and establishes a criterion for identifying redundant models on the basis of the incremental change in the IS of the combination after a model is removed. Initially, the combination includes all the models, and the models with lower marginal contributions are sequentially removed until all the redundant models are eliminated. To further optimize the weighting of the combined models, interval Bayesian weighting, inverse CWC weighting, and inverse IS weighting methods are introduced, with the final combination determined via the best-performing interval Bayesian weighting method. As a result, MSIFC–SV avoids the complexity of an exhaustive search across all possible model combinations, thereby enhancing the efficiency of model selection.

A series of comparative experiments on carbon price datasets demonstrate that the proposed algorithm outperforms its derived subsets, the optimal individual prediction, and subsets selected by benchmark algorithms such as the HLN test, encompassing test, CEI, MI, and RRLS in terms of the PICP, MPIW, CWC, and IS. The empirical analysis validates the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed algorithm, providing a new perspective and practical tool for model selection in interval combination forecasting.

However, some challenges remain. First, the computational cost of calculating Shapley values is high when addressing large datasets and numerous models. Second, existing comprehensive interval metrics, such as CWC and IS, have limitations and may not always accurately measure model performance. In future research, we will focus on improving the efficiency of Shapley value computation and developing more accurate comprehensive evaluation metrics for interval forecasting.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available at http://www.tanpaifang.com/ and https://lib.stat.cmu.edu/datasets/boston. The code supporting this study is available upon request from the corresponding author, Prof. Huayou Chen, at huayouc@126.com.

References

Fang, Y. Forecasting combination and encompassing tests. Int. J. Forecast. 19(1), 87–94 (2003).

Costantini, M. & Pappalardo, C. A hierarchical procedure for the combination of forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 26(4), 725–743 (2010).

Thomson, M. E., Pollock, A. C., Önkal, D. & Gönül, M. S. Combining forecasts: performance and coherence. Int. J. Forecast. 35(2), 474–484 (2019).

Mendes-Moreira, J., Jorge, A. M., Soares, C. & de Sousa, J. F. Ensemble learning: A study on different variants of the dynamic selection approach. In Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition: 6th International Conference, MLDM 2009, Leipzig, Germany, July 23–25, 2009. Proceedings 6 (pp. 191–205). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. (2009).

Ashton, R. H. Combining the judgments of experts: how many and which ones? Organ. Behav. Hum Decis. Process. 38(3), 405–414 (1986).

Lichtendahl, K. C. Jr & Winkler, R. L. Why do some combinations perform better than others? Int. J. Forecast. 36(1), 142–149 (2020).

Kışınbay, T. The use of encompassing tests for forecast combinations. J. Forecast. 29(8), 715–727 (2010).

Schmittlein, D. C., Kim, J. & Morrison, D. G. Combining forecasts: operational adjustments to theoretically optimal rules. Manage. Sci. 36(9), 1044–1056 (1990).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model461–464 (The Annals of Statistics, 1978).

Swanson, N. R. & Zeng, T. Choosing among competing econometric forecasts: regression-based forecast combination using model selection. J. Forecast. 20(6), 425–440 (2001).

Le An, Y. U., Yang, S., Lai, W. A. N. G., Nakamori, Y. & K. K., & Time series forecasting with multiple candidate models: selecting or combining? J. Syst. Sci. Complexity. 18(1), 1 (2005). (In Chinese).

Harvey, D. I., Leybourne, S. J. & Newbold, P. Tests for forecast encompassing. J. Bus. Economic Stat. 16(2), 254–259 (1998).

Cang, S. & Yu, H. A combination selection algorithm on forecasting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 234(1), 127–139 (2014).

Che, J. Optimal sub-models selection algorithm for combination forecasting model. Neurocomputing 151, 364–375 (2015).

Zhou, Q., Wang, C. & Zhang, G. A combined forecasting system based on modified multi-objective optimization and sub-model selection strategy for short-term wind speed. Appl. Soft Comput. 94, 106463 (2020).

Liu, T., Liu, W., Liu, Z., Zhang, H. & Liu, W. Ensemble water quality forecasting based on decomposition, sub-model selection, and adaptive interval. Environ. Res. 237, 116938 (2023).

Liu, Z., Jiang, P., Wang, J. & Zhang, L. Ensemble forecasting system for short-term wind speed forecasting based on optimal sub-model selection and multi-objective version of mayfly optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 177, 114974 (2021).

Jiang, P., Liu, Z., Wang, J. & Zhang, L. Decomposition-selection-ensemble forecasting system for energy futures price forecasting based on multi-objective version of chaos game optimization algorithm. Resour. Policy. 73, 102234 (2021).

Jiang, P., Liu, Z., Niu, X. & Zhang, L. A combined forecasting system based on statistical method, artificial neural networks, and deep learning methods for short-term wind speed forecasting. Energy 217, 119361 (2021).

Khosravi, A., Nahavandi, S. & Creighton, D. Construction of optimal prediction intervals for load forecasting problems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 25(3), 1496–1503 (2010).

Hamaguchi, Y., Noma, H., Nagashima, K., Yamada, T. & Furukawa, T. A. Frequentist performances of bayesian prediction intervals for random-effects meta‐analysis. Biom. J. 63(2), 394–405 (2021).

Yang, X., Fu, G., Zhang, Y., Kang, N. & Gao, F. A naive Bayesian wind power interval prediction approach based on rough set attribute reduction and weight optimization. Energies, 10(11), 1903. (2017).

Nix, D. A. & Weigend, A. S. Estimating the mean and variance of the target probability distribution. In Proceedings of 1994 IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’94) (Vol. 1, pp. 55–60). IEEE. (1994), June.

Yao, W., Zeng, Z. & Lian, C. Generating probabilistic predictions using mean-variance estimation and echo state network. Neurocomputing 219, 536–547 (2017).

Zhu, S., Luo, X., Yuan, X. & Xu, Z. An Improved long short-term Memory Network for Streamflow Forecasting in the Upper Yangtze River341313–1329 (Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 2020).

Beyaztas, U., Arikan, B. B., Beyaztas, B. H. & Kahya, E. Construction of prediction intervals for Palmer Drought Severity Index using bootstrap. J. Hydrol. 559, 461–470 (2018).

Acharki, N., Bertoncello, A. & Garnier, J. Robust prediction interval estimation for gaussian processes by cross-validation method. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 178, 107597 (2023).

Saeed, A., Li, C., Gan, Z., Xie, Y. & Liu, F. A simple approach for short-term wind speed interval prediction based on independently recurrent neural networks and error probability distribution. Energy 238, 122012 (2022).

Conde-Amboage, M., González-Manteiga, W. & Sánchez-Sellero, C. Predicting Trace gas Concentrations Using Quantile Regression Models311359–1370 (Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 2017).

He, Y. & Li, H. Probability density forecasting of wind power using quantile regression neural network and kernel density estimation. Energy. Conv. Manag. 164, 374–384 (2018).

Zhang, W., Quan, H. & Srinivasan, D. Parallel and reliable probabilistic load forecasting via quantile regression forest and quantile determination. Energy 160, 810–819 (2018).

Khosravi, A., Nahavandi, S., Creighton, D. & Atiya, A. F. Lower upper bound estimation method for construction of neural network-based prediction intervals. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks. 22(3), 337–346 (2010).

Wu, Q., Lin, J., Zhang, S. & Tian, Z. A theil coefficient-based combination prediction method with interval heterogeneous information for wind energy prediction. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 41(1), 1031–1048 (2021).

Wang, P., Tao, Z., Liu, J. & Chen, H. Improving the forecasting accuracy of interval-valued carbon price from a novel multi-scale framework with outliers detection: an improved interval-valued time series analysis mode. Energy Econ. 118, 106502 (2023).

Meira, E., Oliveira, F. L. C. & Jeon, J. Treating and pruning: new approaches to forecasting model selection and combination using prediction intervals. Int. J. Forecast. 37(2), 547–568 (2021).

Long, H., Geng, R. & Zhang, C. Wind speed interval prediction based on the hybrid ensemble model with biased convex cost function. Front. Energy Res. 10, 954274 (2022).

Shapley, L. S. A value for n-person games. Contribution to the Theory of Games, 2. (1953).

Huayou, C. H. E. N. A kind of cooperative games method determining weights of combination forecasting. Forecasting 22(1), 75–80 (2003). (In Chinese).

Ding, Z., Chen, H. & Zhou, L. Using shapely values to define subgroups of forecasts for combining. J. Forecast. 42, 905–923 (2023).

Schmidhuber, J. & Hochreiter, S. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9(8), 1735–1780 (1997).

Lai, Y. et al. Exploring uncertainty in regression neural networks for construction of prediction intervals. Neurocomputing 481, 249–257 (2022).

Hu, J., Lin, Y., Tang, J. & Zhao, J. A new wind power interval prediction approach based on reservoir computing and a quality-driven loss function. Appl. Soft Comput. 92, 106327 (2020).

Salem, T. S., Langseth, H. & Ramampiaro, H. Prediction intervals: Split normal mixture from quality-driven deep ensembles. In Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 1179–1187). PMLR. (2020), August.

Yan, L., Verbel, D. & Saidi, O. Predicting prostate cancer recurrence via maximizing the concordance index. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 479–485). (2004), August.

Quinonero-Candela, J., Rasmussen, C. E., Sinz, F., Bousquet, O. & Schölkopf, B. Evaluating predictive uncertainty challenge. In Machine Learning Challenges Workshop (1–27). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. (2005), April.

Pearce, T., Brintrup, A., Zaki, M. & Neely, A. High-quality prediction intervals for deep learning: A distribution-free, ensembled approach. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 4075–4084). PMLR. (2018), July.

Wang, B., Li, T., Yan, Z., Zhang, G. & Lu, J. DeepPIPE: a distribution-free uncertainty quantification approach for time series forecasting. Neurocomputing 397, 11–19 (2020).

Efron, B. & Tibshirani, R. J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1994).

Ni, Q., Zhuang, S., Sheng, H., Wang, S. & Xiao, J. An optimized prediction intervals approach for short term PV power forecasting. Energies 10(10), 1669 (2017).

Winkler, R. L. A decision–theoretic approach to interval estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 67(337), 187–191 (1972).

Maciejowska, K., Nowotarski, J. & Weron, R. Probabilistic forecasting of electricity spot prices using factor Quantile Regression Averaging. Int. J. Forecast. 32(3), 957–965 (2016).

Darbandsari, P. & Coulibaly, P. Assessing entropy-based bayesian model averaging method for probabilistic precipitation forecasting. J. Hydrometeorol. 23(3), 421–440 (2022).

Xie, Q., Hao, J., Li, J. & Zheng, X. Carbon price prediction considering climate change: a text-based framework. Economic Anal. Policy. 74, 382–401 (2022).

Duan, S. et al. LightGBM Low-Temperature Prediction Model based on LassoCV Feature Selection. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021(1), 1776805 (2021).

Gaba, A., Tsetlin, I. & Winkler, R. L. Combining interval forecasts. Decis. Anal. 14(1), 1–20 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72371001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingling Yang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Liren Chen: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Huayou Chen: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Chen, L. & Chen, H. Shapley value-driven superior subset selection algorithm for carbon price interval forecast combination. Sci Rep 15, 7087 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90006-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90006-2