Abstract

This study explores a novel technique of preparing porous ceramics using egg white protein foaming method, in which hydrophobically modified Al2O3 particles self-assembly on the surface of protein bubbles to form a stable foam slurry, which is ultimately discharged and sintered to make porous Al2O3 ceramics. And egg white protein was a non-toxic and harmless natural substance that functions simultaneously as a foaming agent, a binder, and a gelling agent, has a significant advantage over ordinary foaming agents. The effect of protein foam content on the microscopic morphology, pore distribution, and strength of the porous ceramics was investigated. The mechanism of porous ceramics prepared by the protein foaming method was analyzed and the reliability of the study was verified by simulating the possible bonding with Gaussian 6.0. Porous ceramics with open porosity of 11.2–38.82%, near-spherical shape, average pore size of 150–240 μm, and compressive strength of 84–140 MPa were fabricated. The thermal insulating results showed that the porous ceramics have good thermal insulation performance, which was expected to be applied in the fields of aviation heat shields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porous ceramics are widely employed in molten metal filtration, biologically functional materials, catalyst carriers, and sound absorption and insulation because of their unique pore structure, and high-temperature resistance. The conventional methods for preparing porous ceramics include the foaming method, replica method, pore-making agent method, and extrusion method1,2,3,4,6. The foaming method is the most commonly used and simplest to operate. Common foaming agents can be classified into chemical synthetic foaming agents and natural foaming agents. Proteins are ideal natural blowing agents because they are widely available, biocompatibility, and in the preparation of porous ceramics can simultaneously play the role of foaming, bonding, and gelation. This gives them a significant advantage over the single-function chemical blowing agent.

Several studies have synthesized porous ceramics, employing protein foaming technique. The work of7 explored the macroporous ceramic samples prepared through sponge replication and egg white protein foaming techniques. Results revealed that the samples prepared using direct protein foaming technique exhibited greater strength and a more uniform pore structure with similar porosity than replication method. Santanu Dhara8 produced alumina foams with porosities ranging from 50 to 92% by foaming and coagulating ovalbumin-based aqueous slurries. The results show that controlling the viscosity of the slurry controls the total porosity, microstructure and mechanical properties.

Liuyan Yin et al.9 prepared silicon nitride (Si3N4) foams with ultrathin cell walls using a protein foaming technique by increasing the air fraction of the foamed slurry. The produced Si3N4 foams showed a polyhedral shaped pores, with pore wall thickness measuring only 2–3 mm.

Furthermore, Liuyan Yin10 investigated the influence of ball milling rotational speed on the pore size distribution and the properties of silicon nitride foams prepared by egg white protein foaming. The study revealed that the pore sizes of Si3N4 foams followed a logarithmic normal distribution, with the pore structures becoming more homogeneous as the rotational speed increased within a specific range. The pore structure becomes more uniform. Study11 prepared hydroxyapatite (HAP) porous material by using protein as a pore-making agent in which protein provides 86% porosity. The research12 fabricates lightweight, high-strength, in-situ self-reinforced Si3N4 ceramic foams, with compressive strength ranging from 13.2 to 45.9 MPa by using a combination of the protein foaming technique and the sintering reaction bonding technique. V Rybakov13 explored the flammability of monolithic foam concrete, incorporating a protein- blowing agent with a density of 200 kg/m3, which was used in a lightweight steel-framed concrete structural form of the envelope.

Foam exhibits high surface free energy, resulting in a thermodynamically unstable system, and tends to reduce the surface free energy spontaneously by reducing the specific surface area. This trend is manifested in the macroscopic instability of foam, that is, loss of liquid, polymerization, and disproportionation (coarsening)14. However, these instabilities can be effectively managed to ensure the stability of ceramic foam system is improved by adding surfactant15, protein and its nano polymer16 and solid particles. This reassures us of the reliability and robustness of our research in the production of porous ceramics.

From the energy perspective, solid particles have significantly higher adsorption energy of at the interface than that of surfactants, making them challenging to desorb once adsorbed. Researchers have found that the adsorption of solid particles on the foam interface membrane is irreversible17, resulting in good foam stability when reinforced with solid particles. Guackler18 used short-chain amphiphilic molecules to hydrophobically treat Al2O3 particles resulting in their irreversible adsorption on the gas-liquid interface and improving foam stability. Gonzenbach17 introduced air into an aqueous suspension containing hydrophobic particles modified by surfactant to obtain foam embryos, which were then dried and sintered to form foam ceramics. In this study, ultrahigh porosity and ultralight Al2O3 foam with a porosity of 94.7 ~ 98.3% and a density of 0.067 ~ 0.210 g/cm³ were successfully prepared for the first time. The sintered foam ceramic has a single particle wall and uniform foam pores, with a pore size of 50 nm ~ 20 μm. Furthermore, Huo Wenlong19,20 modified the Al2O3 ceramic powder using cetyl sodium sulfate, prepared particle-stabilized foam with a slurry solid content of 8% ~ 40% by stirring and foaming, dried at room temperature, and sintered at 1550 ℃ for 2 h to obtain ultra-light Al2O3 foam ceramics with porosity of 91.1% ~ 99.8%. Moreover, Bernard P. Binks21 silicified hydrophilic silica with dichlorodimethylsilane to obtain silica nanoparticles of different hydrophobic grades, eventually synthesizing ultra-stable foam stabilized solely by hydrophobic particles, with the particles gathering on the surface of micron-sized bubbles.

The methods of protein foaming and solid particle reinforcement have a long history, but there have been limited instances of combining these two methods. In this study, egg white protein was used as the foam skeleton, and then sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was utilized to treat Al2O3 hydrophobically. This system facilitates self-assembly of protein and solid particles on the surface of the foam, producing a ceramic foam body with remarkable stability. Following gel removal and sintering, Al2O3 porous ceramics with high porosity and remarkable strength were successfully synthesized. This study is expected to realize the controllable change of pore size in porous ceramics through the modulation of protein structure.

Experiments

Materials

Al2O3 powder (D50 = 0.83 μm, purity ≥ 99.0%) used here was purchased from Henan Jiyuan Brothers Materials Co., Ltd. and was used as raw material. In addition, 2.5 wt% Y2O3 (Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemical Co., Ltd, D50 = 0.35 μm, purity ≥ 99.0%) and 2.5 wt% SiO2 powder (Guangzhou Jinhua Da Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, D50 = 90.63 μm, purity ≥ 99.7%) based on the weight of Al2O3 powder were added as sintering aids. The particle morphology and size of raw material powders is show in Fig. 1. ACUMER9300 (Rohm and Hass, Germany) was selected as a dispersant to stabilize Al2O3 powder in protein-water suspension. The egg used was purchased from the market, and the egg white protein was derived by separating the egg white and egg yolk. SDS (analytical pure, Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory, purity ≥ 99.7%) was used for hydrophobic treatment of Al2O3 ceramics.

Preparation of slurry

The Al2O3 powder was first prepared by ball-milling in a 500 ml bottle for 4 h at 300 rpm. After the ball-milling, the Al2O3 powder was cleaned up with water and alcohol and then dried to be used. The Al2O3 slurry was prepared by first dispersing Y2O3 and SiO2 powder in distilled water by magnetic stirring for 30 min. Then Al2O3 was added and stirring continued for 60 min. A certain amount of SDS was added to the prepared slurry by adjusting its pH and dosage, and the Al2O3 was subjected to hydrophobic treatment.

Preparation of porous ceramic

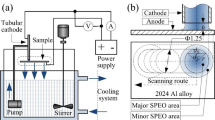

The preparation of porous ceramic involves a unique step that sets our procedure apart. The egg white protein is a key component, separated from the fresh egg, and whipped to foam. The foam is then added to the previously prepared Al2O3 slurry in a certain volume ratio. The obtained foam slurry is cast in a cylindrical mould, with a layer of oil applied to the interior of the mould before casting to facilitate demoulding. The mould is then placed in a water bath at 70 °C for 1 h, removed and left to stand for 24 h at room temperature before being thoroughly dried. The porous ceramics are then calcined at 600 °C for 1 h to remove proteins and other organic substances, and finally sintered at 1500 °C for 1 h to obtain the porous ceramic. A sketch of the prepared porous Al2O3 ceramics is shown in Fig. 2.

Characterization

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the sample was performed by a synchronous thermal analyzer (Netzsch STA449 F3) within the range ambient temperature to 700 ℃ (10 ℃/min). Open porosity was determined using the Archimedes technique. The pore structure was analyzed using SEM (FEI Quanta-450-FEG), and pore distribution was determined using Nano Measure 1.2.

The infrared spectral absorption of the porous vein blanks and sintered samples was measured using a Fourier transform spectrometer (PerkinElmer Spotlight 400) with a resolution of 4 cm− 1 in the range of 450–4000 cm− 1. The compressive strength of the porous ceramics was tested by WDW-20 electronic universal testing machine (Jinan Chuanbai Instrument and Equipment Co., Ltd.) with three to five specimens to determine the average value. The Al2O3 powder was made into thin sheets and the surface water contact angle was measured using OCA40MICRO (Dataphysics Instrument GmbH). The crystal structure was analyzed using a DMAX - RAPID II X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku) with a Cu emission source, a test angle ranging from 5° to 90°, a scanning speed of 10°/min, a voltage was 40 kV, and a current was 30 mA. The possible reactions between Al2O3, SDS and protein amino acid side chains in the slurry were carried out by Gaussian 6.0 respectively. The samples temperature was monitored using an Nbw-946 S (Lan Ba Wan ) heating table, and a FLIR ONE PRO (Teledyne FLIR ) camera, and a dense Al2O3 ceramic block used as a control. The thermal conductivity of the porous sample and the control sample at room temperature were conducted by TC3000E thermal conductivity tester (Xiaxi).

Result and discussion

Thermal treatment and structural

Egg white protein plays the dual role of bonding and gelation in the porous structure. Suppose the temperature is raised rapidly during the burn-off process. In that case, it will result in rapid oxidation of the protein and other organic materials rapidly generating a large amount of gas. This can cause cracking and pulverization of the sample, and even collapse, affecting the pore structure and the overall strength. Therefore, increasing the temperature gradually and adopting a phased approach during the process is essential.

In order to clarify the thermal history of Al2O3 porous ceramics during the heating process, the thermogravimetric analysis was used to characterize the TG-DTG curve of porous ceramic from room temperature to 750 ℃. As shown in Fig. 3a, when the temperature is less than 80 °C, the weight of the sample mass decreased due to the rapid volatilization of free water. During the temperature increase to ~ 500 ℃, the weight of the sample decreases significantly, while this weight loss phenomenon continues until 650 ℃. By studying the TG curve, it can be found that the sample mass loss is about 13.61% during the temperature increase to ~ 650 ℃, which corresponds to several endothermic peaks on the DTG curve, which is due to the decomposition and volatilization of proteins. When the temperature is higher than 650 ℃, the organic matter is completely decomposed and the sample mass remains basically unchanged.

To verify the applicability of the designed burn-off process for proteins, infrared spectroscopy is done on Al2O3 porous embryos and ceramics. Figure 3b, presents the results, showing an absorption band at 1658 cm− 1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of C = O in amide. The 1437 cm− 1 is attributed to the C–N stretching vibration spectrum, while the bands around 1035 cm− 1 suggests the presence of stretching vibration of C–C, and the bands around 1107 cm− 1 indicate asymmetric stretching vibrations of Si atoms against O atoms in Si–O–Si bonds22. These findings confirm the presence of protein and SiO2. In the sintered infrared spectrum, all protein absorption peaks disappeared, indicating the complete burned-off of the protein.

Thermal treatment and structural of porous ceramic. (a) TG - DTG analysisof Al2O3 porous green body, (b) FTIR spectrum of Al2O3 porous green body and Al2O3 porous ceramic, (c) XRD patterns of Al2O3 raw powder and porous green body of porous ceramic, (d) the contact angle of Al2O3 raw and hydrophobic powder.

The XRD spectra presented in Fig. 3c reveal Al2O3 raw powder, porous green body and ceramics after calcination at 1200 °C. The results reveal that the peaks of Al2O3 remain pure and well characterized with the index number Al2O3, No. 10–0173. In Fig. 3c, the raw Al2O3 powder and the porous ceramic green body as well as the porous ceramic have small diffraction peaks around 28°, which may be caused by trace impurities in the raw material. The characteristic absorption peaks of the control three samples under investigation remain unchanged, suggesting that the crystalline form of Al2O3 is consistent before and after sintering. Furthermore, Fig. 3d compares water contact angle on Al2O3 powder before and after hydrophobic treatment. The water contact angle on the surface of the unmodified Al2O3 powder is less than 90°, while the contact angle after treatment is more than 90°, confirming hydrophobicity. The interaction between Al2O3 in an aqueous solution and the anions generated by the ionization of SDS, causes the adsorption of SDS the Al2O3 surface. Following this hydrophobic modification, Al2O3, can generate abundant forces with protein foam, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic forces, ultimately contributing to solid particle - enhanced foam.

Micro-structure

Figure 4a shows the Al2O3 wet foam foamed using egg white protein. The foam appears dense, the cell size is uniform, and there is no solid particle precipitation at the bottom. Even after several hours at room temperature, the foam remains stable without significant defoaming or precipitation. This shows that Al2O3 particles and egg white protein form a stable wet foam, with Al2O3 is evenly distributed on the protein foam skeleton. Figure 4b presents a physical view of the porous ceramics. Figure 4c showing a significant increase in porosity with the rise in protein foam content. However, the porosity decreases slightly when the protein volume ratio reaches 50 vol%. This is because when the volume of protein is relatively low, most of the slurry is occupied by solid particles and there are few bubbles. With the increase of the volume ratio of protein, the proportion of bubbles is higher, leading to gradual increase in the porosity. However, excessively high protein volume ratio causes interconnected pores, reducing the detectable porosity. Figure 4d presents an enlarged cross-section of the porous ceramic, indicating the presence of many regularly arranged holes in the interior of the sample. The shape of the pores is close to spherical with sizes ranging from micrometers to millimeters. Most of the pores are closed, while some have openings in the walls. When protein foaming is used to create wet foams, the resulting pore structure is primarily spherical and uniform. However, when these wet foams are mixed with the ceramic slurry to form the foam slurry and during the curing process, the structure of the pores can change or even partially collapse. Curing ceramic porous slurry is a very complex process, which involves the denaturation of proteins, the formation of spatial network skeleton, and accompanied by the growth of bubbles, merging, and bursting, which ultimately affects the structure of porous ceramics. Figure 4e, reveals that the pillar walls in the middle of the cell are composed of accumulation of Al2O3 particles. In contrast, the thinner parts of the pore walls are formed by the accumulation of only one or more layers of particles. Further magnification shows the morphology of the Al2O3 crystal particles as shown in Fig. 4f.

Porosity and morphology of Al2O3 porous ceramic. (a) Al2O3 wet foam, (b) Al2O3 ceramic sample with a density of 1.14 g/cm3 and porosity of 38.82% standing on a leaf, (c) porosity of Al2O3 ceramics with different content of protein foam, (d) porous morphology of Al2O3 ceramics (with a density of 1.14 g/cm3 and porosity of 38.82%), (e) (f) local amplification.

Figure 5 presents the changes of pore morphology and size distribution of porous ceramics made from protein foam with varying volume contents. The ceramic exhibits a few big holes when the protein is 10 vol%, and the mean size is 180 μm. As the volume of protein foam increases, the number of pores gradually increased (a–e), and the distribution diagram showed a more uniform size distribution of smaller pores. The pore size distribution of the porous ceramics was narrowest when the protein volume dosage was 40%, with an average size of 150 μm. In Fig. 5a–e, it can be found that the pore size within the porous ceramics shows a tendency to become larger and then smaller as the protein foam volume increases from 10 vol% to 50 vol%. When the protein content is 10 vol%, most of the foams are dispersed in the slurry independently, forming ceramic with only a few pores. With the increase of protein foam in the slurry, more aggregation and merging of the foam occurred, resulting in a decrease of small bubbles and an increase of large bubbles. When the protein content is 20 vol%, more small bubbles merge into individual large bubbles, so that the porous ceramic exhibits the widest pore size distribution. Further increase in protein foam, the foam occurs more aggregation, while under the stirring force, restricting the foam in the slurry infinitely larger, and ultimately form a relatively uniform size of the large holes.

Mechanism analysis of porous ceramic preparation

In Fig. 6, the mechanism of preparing porous ceramics using egg white protein is briefly illustrated. Egg white protein, comprising 90% water and 10% protein bound by hydrogen bonds transforms under high-speed stirring. This process breaks the weak hydrogen bonds in the protein molecules, partially elongating the amino acid chains. As a result of the varying hydrophilicity of the molecular chains, the protein molecules swiftly form a directional arrangement at the gas-liquid interface. Here, the hydrophilic end is oriented in the aqueous solution, while the hydrophobic end faces the gas bubble. Under external force, the protein wraps around the gas, giving rise to the formation of bubbles. Subsequently, these bubbles aggregate to form a relatively stable bubble network. After the protein wraps the gas bubbles, an interfacial membrane of a certain thickness is formed on the surface of the bubbles, exposing the reactive groups, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic groups. These groups allow the surface-modified Al2O3 particles to interact with the bubble surface stably. These particles, once adsorbed, exhibit remarkable foam stability as they are difficult to desorb. The fully mixed foam slurry is then injected into the mold and heated in a water bath at 70 °C to promote protein denaturation and further forming porous skeleton. Finally, through the process of curing, drying, and sintering, the organic matter such as egg white protein is burned off to form porous ceramics.

In this study, Gaussian simulations of the possible reactions between Al2O3, SDS and protein amino acid side chains in the slurry were carried out respectively. The energy values before and after the combination are shown in Table 1, the electron cloud diagram is shown in Fig. 6.

Na+ in SDS is extremely unstable and readily dissociates into solution, resulting in a potentially negative charge for the dodecyl sulfate ion. After the ionized Na+ combines with Al3+ in a 3:1 ratio, the energy decreases from − 1333.357255 (a.u.) to -3755.574324 (a.u.), which indicates that SDS can combine with Al2O3 and form a stable structure. This is consistent with the simulated image of the electron cloud in Fig. 7a,a1, the overall image of the electron cloud formed by combining the two is not charged, showing a stable structure. In Table 1, the binding energies of SDS, Al3+ and five amino acid side chains are compared respectively. From the data before and after the binding, it can be seen that the energies of SDS binding with amino acid side chains are lower than those with Al3+, indicating that Al2O3 is more likely to bind with proteins and form stable structures after hydrophobically modified by SDS. The electron cloud diagrams of the side chains of five amino acids are simulated in Fig. 7b–f. As can be seen that, there are brighter regions in each amino acid side chain, which can be considered as active sites. Their electron cloud diagrams after binding with Al3+ are shown in Fig. 7b1–f1 and binding with SDS in Fig. 7b2–f3. As can be seen from the figures, the original bright spot region disappears, which is due to the mutual bonding of the amino acid side chains with Al3+ and SDS in this region, thus forming a more stable junction and lowering the overall energy. The results of this electron cloud simulation are consistent with the results of energy calculations and with the mechanism of slurry assembly on the foam surface, verifying that the hydrophobically modified alumina is more easily assembled on the foam surface to form a stable porous structure.

Electron clouds of the steady state configurations of each substance, and their steady state configurations after binding with Al3+ and SDS (binding energies are arranged from low to high). (a) SDS; (a1) Al3+ with SDS; (b) (CH2)4NH3+; (b1) (CH2)4NH3+ with Al3+; (b2) (CH2)4NH3+ with SDS; (c) -CH2C6H6; (c1) CH2C6H6 with Al3+; (c2) CH2C6H6 with SDS; (d) CH2COO−; (d1) CH2COO− with Al3+; (d2) CH2COO− with SDS; (e) CH(CH3)2; (e1) CH(CH3)2 with Al3+; (e2) CH(CH3)2 with SDS; (f) CH2OH; (f1) CH2OH with Al3+; (f2) CH2OH with SDS.

Mechanical strength

The compressive strength of porous ceramics fabricated using varying amounts of protein foam was measured and the effect of SDS on it was compared, and the results are shown in Fig. 8.

In Fig. 8a, the force curve of a porous ceramic is jagged, typical fracture curve of a porous ceramic. This is a result of many cracks within the porous material. When the sample is subjected to force, the internal cracks constantly deflected, making the stress to fluctuate, resulting in a jagged curve. Figure 8b shows the strength comparison of porous ceramics made with or without the addition of SDS at different volume fractions of protein foam. From the figure, it can be seen that as the volume fraction of protein foam increases, the compressive strength of porous ceramics shows a decreasing trend, which is due to the fact that in a certain range, the larger the volume fraction of protein foam, the higher the porosity of porous ceramics, which brings about a decrease in compressive strength. From Fig. 8b, it can be seen that the compressive strength of porous ceramics with the addition of 0.2 wt% SDS is significantly higher than that of the unadded one. The compressive strength of the porous ceramic reaches 121 MPa when the protein foam is 40 vol%. This is consistent with the mechanism of solid particle-reinforced foam and also agrees with the results of Gaussian calculations. This verifies the solid enhancing effect of Al2O3 particles on the foam surface. Due to the addition of SDS, the surface of hydrophilic Al2O3 particles becomes hydrophobic and can form effective bonds with the surface of the protein foam, which ultimately leads to the formation of porous ceramics with higher bubble strength.

Thermal insulation properties

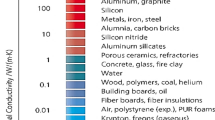

Figure 9 presents the temperature changes of the sample and the control group recorded by the thermal imaging camera within 80 s after contacting the hot table. The round sample is Al2O3 porous ceramic, and the square sample is Al2O3 ceramic block. The temperature difference between the sample and the control group is minimal within 5 s of initial contact. However, at 10 s, the temperature of the control group rises rapidly. The temperature of the control sample exceeded 116 ℃, whereas the porous ceramic was approximately 60.8 ℃, indicating highly effective heat insulation properties of porous ceramic. Over time, the temperature of both the sample and the control increased gradually. At 220 s, the temperature of the sample attained 115 ℃, while the temperature of the control group exceeded 150℃. Even with the prolonged contact time with the hot table, the temperature difference between the two remains about 40 ℃. Al2O3, being a good conductor of heat, induces a rapid temperature rise in the control group upon contact with the hot table. In contrast, porous Al2O3 ceramics contain numerous non-conductive air-filled holes that absorb and dissipate heat. The interconnected holes in the porous ceramics allow heat to escape into the surrounding area, leading to reduced temperature within the sample and remarkable heat insulation effect. The thermal conductivity of the porous ceramic was 0.077 W/ (m×K) and the control sample was 3.164 W/ (m×K). Materials with a thermal conductivity of less than 0.2 W/ (m×K) are generally often referred to as thermal insulation materials. The above results proved that the samples were thermally insulating.

Conclusion

In this study, surface modification of Al2O3 was carried out using amphiphilic surfactants to turn hydrophilic Al2O3 particles into hydrophobic ones. Subsequently, protein molecules were manipulated via physical stirring to form a directional arrangement at the gas-liquid interface, wrapping air to form bubbles. The protein bubbles were then assembled with the modified Al2O3. After curing and sintering, porous Al2O3 ceramics with a porosity of 38.82%, a compressive strength of 121 MPa, a density of 1.14 g/cm³, and certain thermal insulation were successfully produced for 40 vol% egg white protein foam. Compared with the traditional protein foaming method, this technique improves the foam stability and has enhances pore structure. Further study is required to optimize the preparation process and structure of protein to obtain porous ceramics with controllable pore size and regular shape.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data generated or analysed during this study are available within the paper . Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Potoczek, M., Zima, A., Paszkiewicz, Z. & Slósarczyk, A. Manufacturing of highly porous calcium phosphate bioceramics via gel-casting using agarose. Ceram. Int. 35 (6), 2249–2254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2008.12.006 (2009).

Krajewski, A., Ravaglioli, A., Roncari, E., Pinasco, P. & Montanari, L. Porous ceramic bodies for drug delivery. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 11 (12), 763–771. (2000).

Ploux, L. et al. New colloidal fabrication of bioceramics with controlled porosity for delivery of antibiotics. J. Mater. Sci. 51 (19), 8861–8879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-016-0133-z (2016).

Liu, S., Liu, J. C., Hou, F. & Du, H. Y. Microstructure and properties of inter-locked mullite framework prepared by the TBA-based gel-casting process. Ceram. Int. 42 (14), 15459–15463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.06.197 (2016).

Wang, Y. F., Zhang, C. R., Feng, J. & Jiang, Y. G. Fabrication and properties of SiO2-aerogel/ short silica porous skeleton composite. J. Chi Ceram. Soc. 37 (02), 387–390. (2009).

Yan, S. et al. Effect of fiber content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of carbon fiber felt reinforced geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 42 (6), 7837–7843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.01.197 (2016).

He, X. et al. The comparison of macroporous ceramics fabricated through the protein direct foaming and sponge replica methods. J. Porous Mater. 19 (5), 761–766. (2012).

Dhara, S. & Bhargava, P. Influence of slurry characteristics on porosity and mechanical properties of alumina foams. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Tec. 3 (5), 382–392. (2006).

Yin, L. Y., Zhou, X. G., Yu, J. S. & Wang, H. L. Preparation of high porous silicon nitride foams with ultra-thin walls and excellent mechanical performance for heat exchanger application by using a protein foaming method. Ceram. Int. 42 (1), 1713–1719. (2016).

Yin, L. Y., Zhou, X. G., Yu, J. S. & Wang, H. L. Effect of rotating speed during foaming procedure on the pore size distribution and property of silicon nitride foam prepared by using protein foaming method. Ceram Int. 43 (5), 4096–4101. (2017).

Khallok, H. et al. Porous foams based hydroxyapatite prepared by direct foaming method using egg white as a pore promoter. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 55 (2), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41779-018-0269-1 (2019).

Yang, F. Y. et al. Fabrication of in-situ self-reinforced Si3N4 ceramic foams for high-temperature thermal insulation by protein foaming method. Ceram. Int. 47 (13), 18351–18357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.03.156 (2021).

Rybakov, V., Seliverstov, A., Usanova, K. & Rayimova, I. Combustibility of lightweight foam concrete based on natural protein foaming agent. E3S Web Conf. 264, 05001. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126405001 (2021).

Xin Li, B. S., Murrayb, Y. & Yanga Anwesha Sarkarb. Egg white protein microgels as aqueous pickering foam stabilizers: bubble stability and interfacial properties. Food Hydrocoll. (98), 105292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105292 (2020).

Studart, A. R., Innocentini, M. D. M., Oliveira, I. R. & Pandolfelli, V. C. Reaction of aluminum powder with water in cement-containing refractory castables. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25 (13), 3135–3143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2004.07.004 (2005).

Ola Lyckfeldt, J., Brandt, S. & Lesca Protein forming–a novel shaping technique for ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 20 (14–15), 2551–2559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955- (2000).

Rizwan Ahmad Jang-Hoon ha, In-Hyuck Song. Particle-stabilized ultra-low density zirconia toughened alumina foams. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 33 (13–14), 2559–2564. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2013.03.027 (2013).

Gonzenbach, U. T., Studart, A. R., Steinlin, D., Tervoort, E. & Gauckler, L. J. Processing of particle-stabilized wet foams into porous ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90 (11), 3407–3414. (2007).

Huo, W. L. et al. Ultralight alumina ceramic foams with single-grain wall using sodium dodecyl sulfate as long-chain surfactant. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 36 (16), 4163–4170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2016.06.030 (2016).

Huo, W. L. et al. Preparation and properties of alumina ceramic foams prepared with cetyl sodium sulfate. Rare Metal Mat. Eng. 47, 27–31 (2018).

Binks, B. P. & Horozov, T. S. Aqueous foams stabilized solely by silica nanoparticles. Angew Chem. Int. Ed.44 (24), 3722–3725. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200462470 (2005).

Diaz, M. et al. Synthesis, thermal evolution, and luminescence properties of yttrium disilicate host matrix. Chem. Mater. 17 (7), 1774–1782 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52172074), Xi’an Science and Technology Plan Project in 2024 (No. 2024JH-GXFW-0043), the Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial government (No. 23JK0457), the Shaanxi Province 2023 Technical Innovation Guidance Special Fund of China (No. 2023GXLH-039) and the Key Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province in 2024 (No. 2024GX-YBXM-327).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinyue Li: Preparation, creation, and presentation of the work, especially the writing and editing of the first draft. Zi Ye: Study on the mechanism of foaming method. Hua Jiao: Formulation or evolution of overarching research goals and aims. Review and revision of the first draft. Kang Zhao: Oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team. Zixuan Yan: Responsible for the characterization of the porous ceramics.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Ye, Z., Jiao, H. et al. Al2O3 porous ceramics with high strength by protein foaming method. Sci Rep 15, 6424 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90007-1