Abstract

Heart disease is the second leading cause of death in lung cancer (LC) patients, with postoperative cardiovascular disease (CVD) commonly linked to lymph node dissection (LND). This study aimed to clarify the optimal number of lymph nodes (LNs) to be dissected by investigating the impact of LND on CVD related death in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We analyzed data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for a total of 154,566 patients with stage IA-IIIA NSCLC that underwent curative surgery from 2000 to 2020, and further validated using clinical data from a single-center cohort. For patients with negative lymph nodes, the optimal LND threshold was 3 without RT (SHR = 0.909, 95% CI: 0.841–0.982, p = 0.016) and 11 with RT (SHR = 0.877, 95% CI: 0.757–1.015, p = 0.079). For positive lymph nodes (PLNs), 0.53 was the structural breakpoint for the PLNs ratio (p < 0.001). Data from a single-center cohort of 200 patients showed that with LND between 10 and 12, cardiovascular events significantly increased (OR = 18.870, p = 0.044). Excessive dissection of immune-functioning LNs may contribute to the occurrence of death from heart disease and amplify the effects of RT on cardiovascular mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), lobectomy combined with mediastinal lymph node dissection (LND) is considered the standard surgical treatment for early-stage NSCLC according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging1 and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines2. The 5-year survival rate after radical resection of stage I NSCLC is approximately 70%3, suggesting that surgical treatment appears to be highly effective. However, aside from deaths caused by the primary tumor, the cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rate in lung cancer (LC) patients is 5.4%, the highest among all cancers4. Additionally, the incidence of postoperative complications in LC patients is as high as 35%, with CVD being the most common, particularly in elderly patients during the first 3–5 days after surgery5. Obviously, through the above data analysis, the occurrence of CVD following radical lung cancer surgery is an issue that requires closer attention in both clinical practice and research.

LND during radical LC surgery aims to identify and remove metastatic or suspicious lymph nodes (LNs), clarify LNs involvement, accurately determine tumor stage6, assess disease severity, and reduce the risk of recurrence by addressing missed positive LNs7. Studies have also found that the incidence of atrial fibrillation is at least 4 times higher in LC patients after surgery compared to non-cardiothoracic patients (16–46% cardiothoracic surgery vs. 0.4–12% without cardiothoracic surgery)8. Moreover, the occurrence of postoperative atrial fibrillation is associated with intraoperative LND9. Studies have reported that excessive LND can negatively impact the survival of LC patients10 and reduce the effectiveness of immunotherapy in those with postoperative recurrence11. According to epidemiological data, LC patients have the highest incidence of CVD among cancer populations, and heart disease is the second leading cause of death in LC patients4. To date, extensive LND has proven effective in detecting potential metastatic LNs and facilitating postoperative adjuvant therapy, thereby improving long-term survival. However, these benefits may be offset by the increased risk of postoperative CVD. Vieira JM et al. found that cardiac LNs surround the heart and myocardium. The heart relies on lymphatic vessels to maintain fluid balance. Cardiothoracic surgery frequently damages LNs and lymphatic vessels in the heart, which can result in myocardial edema and inflammation, subsequently leading to myocardial fibrosis and, eventually, cardiac dysfunction and heart failure12. Aspelund A et al. also demonstrated that LNs contribute to maintaining cardiac function, and that lymphatic endothelial cells may promote the formation of lymphatic vessels following myocardial infarction or atherosclerosis. This process accelerates interstitial fluid clearance, helping to sustain a healthy cardiac microenvironment and maintain cardiac homeostasis13. Therefore, enlarged LND may lead to the occurrence of CVD and even death from heart disease.

Based on the limited research in the aforementioned literature and the current uncertainty regarding the relationship between LNs status, the extent of dissection, and CVD, we propose the hypothesis that LND impacts the occurrence of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with surgically resected NSCLC. By conducting a comprehensive analysis of database information and validating it with clinical data, we aim to depict real-world scenarios as accurately as possible. This will allow us to further investigate the effect of LND on cardiovascular mortality in these patients and ultimately determine the optimal number of LNs to be dissected.

Materials and methods

Patient population and selection

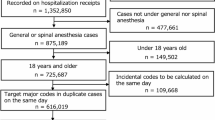

SEER database. Developed by the National Cancer Institute, the SEER database is a comprehensive cancer data collection system that gathers cancer information based large-population across the United States. Its purpose is to facilitate the study of cancer epidemiology and to help develop effective cancer control and prevention strategies. In this study, SEER*Stat (version 8.4.1.1) software was used to search the SEER public database for NSCLC cases and related data from 2000 to 2020. The cause of CVD death in the SEER database and the corresponding codes are: Hypertensive disease (Recode value: 106; ICD-10 Code: I10-I15), Ischemic heart disease (Recode value: 107; ICD-10 Code: I20-I25), Diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries (Recode value: 110; ICD-10 Code: I70-I78). At the same time, we conducted validation in a clinical cohort, and the results were largely consistent.

Chinese institutional registry

We retrospectively gathered data on patients with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection at the Department of Pulmonary Surgery, Shandong Cancer Hospital, People’s Republic of China, between January 2018 and December 2022. The patients were staged according to the eighth edition of the TNM classification. LNs are collected during surgical resection of NSCLC and evaluated and diagnosed by at least two pathologists after surgery to ensure standardized and professional pathologic differentiation. The number of LND in the data was derived from the number of LNs removed by the surgeon intraoperatively and the LNs results identified by the postoperative pathologist. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Cancer Hospital Affiliated with Shandong First Medical University (No. 2024003169). Given the retrospective design of the study and the absence of anticipated risks to participants, patient consent was considered unnecessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The enrolled patients met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the diagnosis of NSCLC was confirmed by histopathological examination; (2) they had undergone surgical resection of NSCLC with LND. Exclusion criteria included: (1) an inadequate number of LND and the absence of relevant clinical features; (2) patients with stage IIIB or IV disease; (3) patients with biopsy-confirmed or suspected multiple primary cancers. The clinicopathological features of the included patients were extracted from the hospital’s electronic information system and included gender, age, histopathological type, lesion location, TNM staging diagnosis, LND, history of hypertension, and preoperative and postoperative myocardial enzyme levels, among others.

This study is a retrospective cohort analysis. Based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 154,566 patients with stage IA-IIIA NSCLC who underwent radical surgery were collected from the U.S. SEER database. Additionally, we collected 200 patients with stage IA-IIIA NSCLC from a hospital in China, who underwent surgical resection with LND, and used this clinical cohort for validation.

Statistical analyses

SEER*Stat from the National Cancer Institute of the United States was utilized to search and download data from the SEER public database. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS statistical system (IBM SPSS Statistics 23, Armonk, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2019. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were utilized to analyze the differences in categorical variables, while frequency distribution histograms were utilized to assess the distribution of LNs counts in both SEER data and clinical data. Stata software (Stata/MP 16.0 for Windows, Revision 02 Jul 2019, USA) was utilized to perform a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards competitive risk model, yielding the subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR). The risk ratio for death due to CVD was calculated by comparing the number of each LND to that of the first LND. In conjunction with the data analysis results, GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.5.1) mapping software was employed, utilizing the default smooth medium level (LOWESS) to plot a smooth curve between the number of LND and the incidence of death from CVD. X-Tile software (version 3.6.1) was applied to determine the structural breakpoint for the optimal number of LND. Additionally, Kaplan-Meier survival curves and forest plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 9. A p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Result

Patient characteristics and distribution of LND

A total of 154,566 patients from the SEER cohort and 200 patients from the Chinese cohort, who met the inclusion criteria, were included in this study. The baseline characteristics of the SEER cohort are presented in Table 1, while the baseline information for the Chinese clinical data is shown in Supplementary Table S1. There were notable differences in the number of LND between the two cohorts. The average number of LND in the Chinese cohort (median of 12; interquartile range 7–16) (Fig. 1b) was higher than that in the U.S. cohort (median of 8; interquartile range 4–14) (Fig. 1a).

Status of LND and risk of cardiovascular mortality

In the SEER cohort, 18,482 patients without LND were excluded, leaving 136,084 eligible patients for further analysis of the impact of LND on cardiovascular mortality. Based on Cox proportional competitive risk model, LOWESS fitting curve of CVD death risk corresponding to the number of LND was obtained to more accurately assess the occurrence of risk (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2a, for patients with negative lymph nodes (NLNs), the risk of CVD decreased as the number of LND increased from 0 to 3. The lowest risk was observed when LNs = 3 were removed, with statistical significance (SHR = 0.905, 95% CI: 0.839–0.976, p = 0.010). When LNs > 3 were dissected, the risk of CVD increased. Nevertheless, for patients with positive lymph nodes (PLNs), a higher number of LNs needed to be removed to reduce the risk of CVD. Specifically, the removal of 26 LNs was associated with a reduced risk. (SHR = 0.948, 95% CI: 0.894–1.004, p = 0.068, Fig. 2b). Similarly, different N stages indicate varying nodal statuses. We incorporated N stage (N1 and N2) into the Cox proportional hazards model with competing risks. The subgroup analysis showed that for patients with N1, the lowest risk of CVD was cleaning 17 LNs (SHR = 0.951, 95% CI: 0.895–1.010, p = 0.101). However, for patients with N2 stage, the dissected of LNs was 26 (SHR = 0.910, 95% CI: 0.811–1.020, p = 0.001, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Specific death of cardiovascular disease. LOWESS smooth curve was used to fit the number of LNs dissected and the risk of CVD, and the optimal number of LNs removed was determined with the lowest risk of death. (a and b) Show the change in CVD mortality risk as the number of LNs removed increases, for NLNs and PLNs. The red circle indicates the lowest risk of death from CVD when this number of LNs is removed. CVD, cardiovascular disease; DLN, dissected lymph node; LNs, lymph nodes; LND, lymph node dissection; N−, negative lymph nodes; N+, positive lymph nodes; NLNs, negative lymph nodes; PLNs, positive lymph nodes; RT, radiotherapy; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Tumor stage and risk of cardiovascular mortality

Due to different lymph node metastases and mortality risk in different clinical stages, we performed a Cox proportional risk competing risk analysis of patients (stages IA, IB, IIA, IIB and IIIA). The study found that for patients in stages IA, IB, and IIA, the lowest risk of cardiovascular death was associated with removing 4 (SHR = 0.929, 95% CI: 0.873–0.988, p = 0.020), 3 (SHR = 0.753, 95% CI: 0.647–0.882, p = 0.001), and 4 LNs (SHR = 0.906, 95% CI: 0.612–1.341, p = 0.062, Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, higher stages require the dissection of more LNs. For stage IIB patients, the dissection of 17 LNs is associated with the lowest risk of CVD mortality (SHR = 0.941, 95% CI: 0.883–1.003, p = 0.061), and for stage IIIA patients, the dissection of LNs was 19 (SHR = 0.936, 95% CI: 0.875–1.002, p = 0.057, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Effects of RT on LND status and CVD mortality

In view of the dual effects of radiotherapy (RT), patients were categorized into two subgroups: those receiving RT and those not receiving it, for further analysis of its impact on CVD mortality. Among patients with all NLNs, the trend in the subgroup without RT remained consistent with the description above. Figure 3a demonstrates that an increased number of LND in the non-RT subgroup (cutoff for LND = 3, SHR = 0.909, 95% CI: 0.841–0.982, p = 0.016) was associated with a higher risk of CVD in patients with stage IA-IIIA NSCLC. Simultaneously, in the RT subgroup, the risk of CVD was lowest when the number of LND = 11 (SHR = 0.877, 95% CI: 0.757–1.015, p = 0.079, Fig. 3b). Additionally, for patients undergoing RT, the risk of CVD gradually increased with the number of LNs removed (LND > 11). Nevertheless, in patients with all PLN (Supplementary Fig. S3), neither the non-RT group (cutoff for LND = 26, SHR = 0.958, 95% CI: 0.903–1.016, p = 0.151) nor the RT group (cutoff for LND = 27, SHR = 1.036, 95% CI: 0.985–1.089, p = 0.168) yielded an appropriate number of LND, and neither reached statistical significance.

Specific death of cardiovascular disease (N−). LOWESS smoothing curve was used to fit the number of LNs removed and the risk of CVD, and the optimal number of LNs removed was determined according to the lowest risk of death. (a) Shows the risk curve of death from CVD with postoperative NLNs without RT. (b) Shows the risk curve of death from CVD with postoperative NLNs in the context of RT. The red circle indicates the lowest risk of death from CVD when this number of LNs is removed. CVD, cardiovascular disease; DLN, dissected lymph node; LNs, lymph nodes; N−, negative lymph nodes; NLNs, negative lymph nodes; Non-RT, non-radiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

The PLNs ratio and the risk of CVD

In the presence of PLNs, the optimal number of LND is influenced by both the number of PLNs and the total number of LND. Therefore, we further investigate the impact of the PLNs ratio (the number of PLNs divided by the total number of LND) on mortality from CVD. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, compared to a PLNs ratio = 0.01–0.30, the PLNs ratio ranging from 0.31 to 0.60 was associated with the lowest risk of death from CVD (SHR = 0.833, 95% CI: 0.698–0.994, p = 0.042). When the PLNs ratio > 0.60, the risk of death from CVD was also reduced; however, this reduction did not reach statistical significance (SHR = 0.957, 95% CI: 0.775–1.182, p = 0.684). Based on the optimal range of the node-positive ratio of 0.31–0.60, the X-Tile technique was employed to determine the optimal cutoff point for the PLNs ratio = 0.53. Subsequently, the primary outcome of interest in this study—death from CVD—was selected for drawing the survival curve. The Kaplan-Meier curve illustrates the survival rates for CVD with a PLNs ratio between 0.31–0.53 and 0.53–0.60, as shown in Fig. 4b. When the PLNs ratio was between 0.31 to 0.53, the median survival time was 37 months. In contrast, when the PLNs ratio ranged from 0.53 to 0.60, the median survival time decreased to only 30 months (p < 0.0001). This indicates that a PLNs ratio = 0.31–0.53 can improve survival from CVD by 7 months. Ultimately, the optimal cutoff value for the PLNs ratio was established at 0.53.

Optimal dissection ratio for PLNs. (a) Association between the rang of PLNs rate and risk of death from CVD. (b) Stratification of CVD survival in patients with node-positive NSCLC with a PLNs rate of 0.53. CVD, cardiovascular disease; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PLNs, positive lymph nodes; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

According to the above research results, the Chinese clinical cohort was validated and analyzed. Correlation analysis of cardiovascular events revealed that age > 65 years (OR = 3.905, 95% CI: 1.220–12.500, p = 0.022), male gender (OR = 3.530, 95% CI: 1.198–10.404, p = 0.022), a previous history of hypertension (OR = 3.890, 95% CI: 1.281–11.815, p = 0.017), an abnormal preoperative electrocardiogram (OR = 3.326, 95% CI: 1.041–10.627, p = 0.043), and the number of LND were all positively correlated with the occurrence of cardiovascular events. Notably, when the number of LND = 10–12, the incidence of cardiovascular events significantly increased (OR = 18.870, 95% CI: 1.082–329.203, p = 0.044, Table 2). It is clear that LND does affect the occurrence of cardiovascular events, and the greater the number of LND may be more detrimental to the cardiovascular system. Based on clinical data from a Chinese cohort, we also analyzed the incidence of abnormal elevations in myocardial injury biomarkers in patients following LC resection. From the Supplementary Fig. S4, it is evident that within one week post-surgery, the most significantly elevated biomarkers were creatine kinase (84.5%) and B-type natriuretic peptide (60.5%), followed by creatine kinase myocardial band (22.0%) and cardiac troponin t (17.0%). Postoperative ECG indicated that 19.5% of patients experienced arrhythmias in the short term, and 21.5% received medication treatment during or after surgery. The most commonly used medications included β-blockers, amiodarone, diuretics, and nitroglycerin.

Discussion

Thus far, there have been limited clinical studies examining the impact of the number of LND on CVD in patients with NSCLC. In this study, we found that: (1) for patients with NLNs, the number of LND ≤ 3; otherwise, the risk of postoperative CVD will increase; (2) for patients with PLNs, the LND ratio should be between 0.31 and 0.53, in conjunction with the number of positive LND and the total number, to minimize the risk of death from CVD; (3) in postoperative patients with NLNs, the risk of CVD increased as the number of LND > 11. Thus, our study to examine the effect of LND on mortality from CVD. Excessive or extensive LND is detrimental to the cardiovascular system, and RT may have an adverse impact in a node-negative environment, leading to an increased number of LND.

As a crucial component of radical lung cancer surgery, systematic mediastinal LND has been regarded as an essential treatment to extend the survival of LC patients and reduce the risk of local recurrence since the 1990s. However, with the emergence of research on selective mediastinal LND, the previous advantages have gradually diminished. In a 2002 randomized controlled trial conducted by Professor Wu Yilong’s team, the median survival time for stage I LC patients following systemic LND was significantly longer than that of the mediastinal LN sampling group (systemic LND: 59 months vs. LN sampling: 34 months), and the survival rate was also significantly higher in the systemic LND group (82.16% vs. 57.49%)14. The study by Lardinois et al. also supported the notion that mediastinal LND leads to longer DFS and a lower recurrence rate in patients with stage I NSCLC compared to mediastinal LN sampling15. However, a multicenter randomized trial with stage T1-2 N0-1 NSCLC compared systemic LND and mediastinal LNs sampling. There was no significant difference in postoperative recurrence rates between the two groups (5-year DFS: 69% for LND vs. 68% for sampling)16. Therefore, it is considered that systematic LND and LN sampling can achieve similar results for early-stage LC. Similarly, Professor Chen Haiquan’s first prospective study on LND methods in 2023 accurately predicted the negative status of all LNs in a specific mediastinal region based on 6 criteria, thereby suggesting the potential for selective LND17. In the current era of immunotherapy, the approach to LND has evolved. Two studies have indicated that the optimal number of LNs to dissect for accurate staging and improved survival is 1610. Furthermore, in patients with postoperative recurrent NSCLC undergoing anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, a lower number of LND (≤ 16) was associated with improved PFS11. The results of follow-up studies clearly supported the conclusions of this research. This study further analyzes the impact of RT factors on the number of LNs removed in patients with either NLNs or PLNs status concerning CVD. Surprisingly, our research found that NLNs patients who received adjuvant RT had a greater number of LNs removed compared to those who did not undergo RT (RT = 11 vs. Non-RT = 3). Corso et al. found that adjuvant RT did not improve the 5-year OS for postoperative NLNs patients (48.0% vs. 37.7%, p < 0.001)18. Another meta-analysis similarly observed that postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) for N0 NSCLC patients was associated with lower OS (HR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.31, p = 0.001), local recurrence-free survival (HR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.24, P = 0.020), and distant recurrence-free survival (HR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25, p = 0.020)19. Building on this study, our research further addresses the role of LND in the context of CVD. RT may impair the immune function of LNs, thereby exacerbating the number of LNs removed. Whether LND simultaneously activates immune function, along with its underlying mechanisms and principles, warrants further investigation. In addition, for postoperative PLNs patients, particularly those with stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC, a large-scale randomized controlled trial in Europe (Lung ART) demonstrated that adjuvant RT could improve DFS (47.1% vs. 43.8%) and reduce local recurrence rates (25.0% vs. 46.1%). However, it is important to note that the mortality rate in the PORT group was higher than in the control group (14.6% vs. 5.3%). Notably, 10.8% of patients in the PORT group experienced grade 3–4 cardiopulmonary toxicity, compared to 4.9% in the control group. The PORT group also had a higher number of deaths due to cardiopulmonary toxicity (16.2% vs. 2.0%) or treatment-related toxic reactions (3.0% vs. 0.0%)20. Unlike previous studies, this paper further explored the relationship between LND and CVD, determining the optimal number of LNs to be dissected. Properly managing the extent of LND can not only enhance the likelihood of preventing recurrence but also reduce the risk of developing CVD and related mortality.

This phenomenon can be explained by several mechanisms. First, lymphatic vessels collect fluid from the tissues and carry it to the LNs. The LNs can produce an immune response and remove antigens from the lymph fluid, which is eventually transported back to the venous system through the thoracic duct and right lymphatic vessels. The LNs and lymphatic vessels make up the lymphatic system, which plays a crucial role in maintaining tissue fluid balance, immune surveillance, and lipid metabolism. Similarly, numerous lymphatic vessels run between the epicardium and the heart muscle, and the cardiac system also relies on lymphatic drainage to help regulate the body’s fluid balance13. In coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, the cardiac lymphatic system transports cholesterol from peripheral tissues and atherosclerotic plaques to the liver for elimination. Nevertheless, following a myocardial infarction, myocardial reperfusion injury can lead to cardiac lymphatic vessel dysfunction, exacerbating myocardial edema and inflammation, and ultimately worsening myocardial fibrosis. Clearly, the cardiac lymphatic system plays a crucial role in maintaining the body’s health21. Secondly, after radical surgery for LC, the disruption of LN structure leads to an increase in systemic inflammatory factors, causing lymphatic transport obstruction and triggering a local inflammatory response. This lowers the threshold for heart fibrillation, preventing the heart from maintaining a relatively stable state and resulting in various CVD, such as arrhythmias22,23,24,25. In mouse models, further research has shown that lymphovascular secretion signals produced by lymphoendothelial cells regulate the proliferation and survival of cardiomyocytes during cardiac development. These signals enhance neonatal heart regeneration and provide cardioprotective effects after myocardial infarction26. It is clear that the lymphatic system plays a crucial role in cardiac homeostasis. Therefore, assessing patients’ cardiac health before LC resection and developing personalized surgical plans can help minimize the impact of LND on the heart during surgery.

In a 2017 study that combined the SEER database with multi-center research in China, a large sample analysis of LND in NSCLC showed that a higher number of LNs removed (from 0 to 16) was associated with better outcomes. However, when > 16 LNs were dissected, survival rates actually decreased. The results indicated that unnecessary excessive LND may reduce long-term survival10. Differently, our study examined the role of LND in the postoperative prevention of CVD, providing relevant insights. We found that when the number of LNs removed > 3, patients faced a higher risk of developing CVD postoperatively. Conversely, for NLNs patients, the occurrence of CVD was lower when the positive rate of LND ranged between 0.31 and 0.53. Consequently, an appropriate LND is not only an important indicator of surgical quality but also affects the incidence of postoperative CVD. Additionally, the calculation of the PLNs rate indirectly assesses the quality and comprehensiveness of LND during surgery27. Even when PLNs are present, analyzing the positive rate helps mitigate the inaccuracies associated with solely relying on the number of positive nodes28. This study not only provides crucial prognostic information for patients but also encourages them to actively participate in their health management, thereby improving treatment outcomes and quality of life. Research on the role of LNs and lymphatic vessels in the cardiovascular system has challenged the traditional belief that “more lymph node dissection is better.” While systematic LND remains critical for accurate cancer staging, it is vital to completely and precisely remove all metastatic LNs with the lowest possible risk to cardiovascular health. Nonetheless, the risk of postoperative CVD should not be overlooked. This study also has several limitations. As it combines data from the SEER database in the United States with clinical samples from China, there are inevitable differences in population characteristics, healthcare systems, and research methodologies between the two groups. Given these considerations, the study specifically analyzed the correlation between the number of LND and cardiovascular events within the clinical cohort. As a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size and single-center design, the findings may not be representative of other regions or populations, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. We currently cannot obtain data on patient comorbidities and surgical margins from the SEER database. This is the weakness of this study. Secondly, there is currently a lack of research exploring the potential mechanisms linking LNR to CVD mortality, which is a limitation of this study. We speculate that this association may be related to inflammation and immune status. A higher LNR indicates more LNs are affected by the tumor, which can promote inflammation, accelerate atherosclerosis, and increase thrombosis29,30,31. Additionally, in normal tissues, LNs maintain cardiac immunity and fluid balance. LNR may reflect the immune status in the tumor microenvironment, influencing the occurrence of CVD32. Further research is needed to provide more insights and evidence about the connection between LNR and CVD. Thirdly, with the advent of the immunotherapy era, a new chapter has been opened for neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy in NSCLC. Both as IMpower01033 and CheckMate-81634, it has shown potential to improve patient prognosis. However, we currently cannot obtain this data from the database, which limits our exploration of it. We look forward to making more discoveries in future research.

The study’s findings offer valuable insights for clinical practice and can guide future treatment and prognosis for patients. For NSCLC patients with NLNs, it is recommended to remove no more than 3 LNs to minimize postoperative CVD risks. However, when undergoing RT, up to 11 LNs should be removed. For patients with PLNs, maintaining a PLNs rate of 0.31–0.60 can reduce the risk of postoperative lymph node metastasis and better control the occurrence of CVD. In addition to assessing lymph node characteristics, considering individual patient features is equally important. Patients with any of the following characteristics should be closely monitored and followed up for prognosis: male gender, age over 65, a history of hypertension, or preoperative or postoperative ECG abnormalities. These factors are high-risk indicators for postoperative CVD and are important for assessing patient outcomes. For these patients, it is advisable to avoid removing 10–12 or more LNs. Once the LNs status and number of nodes removed are established, calculating the positive rate can help evaluate the extent of LND and its prognostic impact. If excessive LND is noted, awareness of potential CVD is crucial, necessitating timely intervention and long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

In NLNs patients, an increased number of LND (cutoff = 3) was associated with a higher risk of CVD in stage IA–IIIA NSCLC patients. Conversely, for PLNs patients, the risk of CVD was lowest with a LND ratio of 0.53. The risk of CVD increased with the number of LND > 11 in patients undergoing concurrent RT. Consequently, excessive dissection of immune-functioning LNs may contribute to the occurrence of heart disease-related deaths and amplify the impact of RT on such fatalities.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- LC:

-

Lung cancer

- LNs:

-

Lymph nodes

- LND:

-

Lymph node dissection

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- NLNs:

-

Negative lymph nodes

- PLNs:

-

Positive lymph nodes

- PORT:

-

Postoperative radiation therapy

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- SHR:

-

Subdistribution hazard ratio

References

Asamura, H. et al. The new database to inform revisions in the ninth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18, 564–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2023.01.088 (2023).

Riely, G. J. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, Version 4.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 22, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2204.0023 (2024).

Rami-Porta, R. et al. Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groups in the Forthcoming (Ninth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 19, 1007–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2024.02.011 (2024).

Raisi-Estabragh, Z. et al. Incident cardiovascular events and imaging phenotypes in UK Biobank participants with past cancer. Heart 109, 1007–1015. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2022-321888 (2023).

Health Commission of Prc, N. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer 2018 (English version). Chin. J. Cancer Res. 31, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.01.01 (2019).

Zhu, Z. et al. A large real-world cohort study of examined lymph node standards for adequate nodal staging in early non-small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 815–825. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-1024 (2021).

Nakagawa, K., Yoshida, Y., Yotsukura, M. & Watanabe, S. I. Pattern of recurrence of pN2 non-small-cell lung cancer: Should postoperative radiotherapy be reconsidered? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 59, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezaa267 (2021).

Chelazzi, C., Villa, G. & De Gaudio, A. R. Postoperative atrial fibrillation. ISRN Cardiol. 2011, 203179. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/203179 (2011).

Cardinale, D. et al. Prevention of atrial fibrillation in high-risk patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: The PRESAGE trial. Ann. Surg. 264, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001626 (2016).

Liang, W. et al. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: A population study of the US SEER database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 1162–1170. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5140 (2017).

Deng, H. et al. Impact of lymphadenectomy extent on immunotherapy efficacy in postresectional recurred non-small cell lung cancer: A multi-institutional retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000000774 (2024).

Vieira, J. M. et al. The cardiac lymphatic system stimulates resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3402–3412. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI97192 (2018).

Aspelund, A., Robciuc, M. R., Karaman, S., Makinen, T. & Alitalo, K. Lymphatic system in cardiovascular medicine. Circul. Res. 118, 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.115.306544 (2016).

Wu, Y. L., Huang, Z. F., Wang, S. Y., Yang, X. N. & Ou, W. A randomized trial of systematic nodal dissection in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 36(1), 1–6 (2002).

Lardinois, D. et al. Morbidity, survival, and site of recurrence after mediastinal lymph-node dissection versus systematic sampling after complete resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 80, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.02.005 (2005). (discussion 274 – 265).

Darling, G. E. et al. Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non-small cell carcinoma: Results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 141, 662–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.11.008 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Selective mediastinal lymph node dissection strategy for clinical T1N0 invasive lung cancer: A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18, 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2023.02.010 (2023).

Corso, C. D. et al. Re-evaluation of the role of postoperative radiotherapy and the impact of radiation dose for non-small-cell lung cancer using the National Cancer Database. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000406 (2015).

Burdett, S., Rydzewska, L., Tierney, J. F., Fisher, D. J. & Group, P. M.-A. T. A closer look at the effects of postoperative radiotherapy by stage and nodal status: Updated results of an individual participant data meta-analysis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 80, 350–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.02.005 (2013).

Le Pechoux, C. et al. Postoperative radiotherapy versus no postoperative radiotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer and proven mediastinal N2 involvement (lung ART): An open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00606-9 (2022).

Song, G. et al. Cardiac lymphatics and therapeutic prospects in cardiovascular disease: New perspectives and hopes. Cardiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000743 (2024).

Oka, T. & Ohkubo, O. Y. Y. Thoracic epidural bupivacaine attenuates supraventricular tachyarrhythmias after pulmonary resection. Anesth. Analg. 93(2), 253–259 (2001).

Ahn, H. J., Sim, W. S., Shim, Y. M. & Kim, J. A. Thoracic epidural anesthesia does not improve the incidence of arrhythmias after transthoracic esophagectomy. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 28, 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.01.017 (2005).

Boos, C. J., Anderson, R. A. & Lip, G. Y. Is atrial fibrillation an inflammatory disorder? Eur. Heart J. 27, 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi645 (2006).

Lamm, G. et al. Postoperative white blood cell count predicts atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 20, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2005.03.026 (2006).

Liu, X. et al. Lymphoangiocrine signals promote cardiac growth and repair. Nature 588, 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2998-x (2020).

Chiappetta, M. et al. Lymph-node ratio predicts survival among the different stages of non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentre analysisdagger. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 55, 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezy311 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. Prognostic value of lymph node ratio in non-small-cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 50, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyz120 (2020).

Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059 (2022).

Jin, Y. & Fu, J. Novel insights into the NLRP 3 inflammasome in atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012219. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012219 (2019).

Ridker, P. M. et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with Canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 (2017).

He, M. et al. Intratumoral tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS) maturation is influenced by draining lymph nodes of lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 11, e005539. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-005539 (2023).

Felip, E. et al. Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after chemotherapy in resected stage II-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. 34, 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.07.001 (2023).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1973–1985. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2202170 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Shandong First Medical University for providing us with their learning platform. And thank you to the patients who contributed information to medical research.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172676, 82373217), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong (ZR2024JQ032), Shandong Natural Science Foundation Major Basic Research Project (ZR2023ZD26), Project supported by the State Key Program of National Natural Science of China (82030082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C., J.Y. and Y.M. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. X.L., P.L. and Y.Q. were responsible for data collection and organization. X.L. and P.L. performed data analysis and draw charts. All authors made significant contributions to the work and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Cancer Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University. Given its retrospective nature, the committee has waived the informed consent requirement for this study. We declare that patients information will be kept confidential and that we adhere to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, X., Li, P., Qin, Y. et al. Excessive lymph node dissection increases postoperative cardiovascular disease risk in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 5698 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90052-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90052-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of lymph node yield on survival of patients with metastatic esophageal cancer: a population-based retrospective study

Discover Oncology (2025)

-

Identification of the lymph node metastasis atlas and optimal lymph node dissection strategy in patients with resectable lung invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma: a real-world multicenter study

Military Medical Research (2025)