Abstract

In vulnerability assessments, accurately determining the indicator weights is essential to ensure the results’ precision and reliability. This paper proposes an optimized comprehensive symmetric Kullback–Leibler (K–L) distance weighting method, in which the comprehensive symmetric K–L distance for each indicator is calculated using a grid-based approach, and the normalized distance serves as the weight for each indicator. ArcGIS software was employed to assess the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability as a case study. The results reveal the following: (1) The grid-based optimized symmetric K–L distance method facilitated variable weight processing in the disaster assessments, where it offered a scientific and adaptable approach for indexing and weighting the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability, thus improving both the evaluation accuracy and practicality. (2) The spatial distribution of the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability levels was uneven, with higher vulnerability observed in the northwestern, southwestern, and southeastern regions, and lower vulnerability in the eastern and northeastern areas. Yining County, Yining City, and certain southern regions of Cocodala City were particularly vulnerable due to multiple influencing factors, including the population, economy, and society. These areas require focused attention and preventive measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural disasters have become increasingly frequent in recent years, with floods, in particular, causing severe impacts. As the socio-economic landscape develops, floods have emerged as the primary hazards in urban areas, posing significant threats to human life and safety while also resulting in substantial economic losses1,2. Consequently, flood risk assessment has become a central focus in disaster prevention and mitigation efforts in river basins3,4. According to Peijun Shi5, the regional disaster system is a structural entity composed of the disaster-prone environment, disaster-inducing factors, and disaster-bearing bodies. The stability of the disaster-prone environment shapes the functioning of this system, the risk posed by disaster-inducing factors, and the vulnerability of disaster-bearing bodies. The vulnerability assessment of disaster-bearing bodies is a critical flood risk assessment component6,7 and typically relies on the economic and social indicators specific to a region to evaluate potential losses due to a disaster. The vulnerability of disaster-bearing bodies is a semi-quantitative social indicator that reflects a region’s sensitivity to disaster-induced losses. It provides valuable insights for regional industrial adjustments and serves as a foundation for decision-making regarding disaster risk reduction investments8.

Some scholars believe that there are five common methods for flood risk assessment9, as well as essentially divided into three methods for flood vulnerability assessment based on the following10,11: analyzing historical disaster data12 (flood events and their resulting losses) and developing a functional relationship between the disaster losses and the flood intensity; systems with multiple indicators13,14, that comprehensively reflect the disaster risk, vulnerability, and exposure; and simulating various flood scenarios based on hydrological–hydraulic models15,16 to assess the potential inundation ranges, depths, and other factors, thus facilitating risk assessments. Among these, the indicator system method is the most commonly used17. As early as 2001, Yunxiao Fan and his colleagues researched the evaluation index system for the vulnerability of disaster-bearing bodies and elucidated its functions, principles, and selection methods8. The methods for determining the weights within the index system exhibit diverse characteristics, primarily categorized into three types: subjective, objective, and comprehensive subjective–objective integration weighting methods18. The subjective weighting method relies on experts’ knowledge, experiences, preferences, and subjective judgments to determine the indicator weights19,20. The core idea of this method is to leverage experts’ in-depth understanding in related fields to assess the various indicators’ importance. Liu et al.18 identified the main subjective weighting methods as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), binomial coefficient, and loop comparison scoring methods. Zheng et al.21 applied the AHP and triangular fuzzy numbers to assess geological disaster risks along the Chengdu–Kunming Railway. Ren et al.22 analyzed the urban waterlogging risk assessment indicator system using an optimal scale transformation and the AHP,

focusing on disaster-inducing factors, the disaster-prone environment, and disaster-bearing bodies. In contrast, the objective weighting method determines weights using mathematical techniques based on the relationships between the original data, without relying on subjective human judgment. This method has a strong mathematical theoretical foundation, making it more objective and scientifically grounded. Many scholars have employed objective weighting methods to assess risk or vulnerability23,24,25. In recent years, machine learning models have also been applied to risk assessments in addition to the entropy weight method26. For example, Wang et al.27 applied four machine learning models—GBDT, XGB, RF, and AdaB—to assess the risk of the “July 20” rainstorm and flood in Zhengzhou City. Finally, the comprehensive subjective–objective integration weighting method combines subjective and objective methods to determine weights while accounting for subjective judgment and objective data. This approach aims to achieve a more comprehensive and reasonable weight distribution. Increasingly, scholars have opted for this method in disaster risk assessments28,29, with the evaluation results consistently showing that the combined method yields more accurate outcomes than either weighting method alone. Overall, the method for determining indicator weights plays a crucial role in the vulnerability assessment of disaster-bearing bodies using traditional indicator system methods. These methods typically rely on a large amount of indicator data or professional knowledge and experience to calculate the weight coefficients through mathematical processing of the indicator data. They offer the advantages of scientific rigor, a systematic approach, and simplicity, and they are widely applied in risk assessment30, decision analysis31, environmental science, planning applications32, and other fields. However, the weight results obtained using these methods are often single numerical values, which fail to reflect spatial variations in the weight distribution. In disaster risk assessment, regional differences in influencing factors require differentiated weights, a concept known as variable weight theory33. This theory adjusts the weights to reflect the importance of different factors under varying conditions, making the evaluation results more accurate and reasonable. The variable weights allow for spatial adaptations to specific regional conditions, providing more flexible and detailed decision support for disaster risk assessment.

In addition to the methods for determining weights mentioned above, some scholars have recently used the symmetric Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance as a weighting method. The Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance, also known as the Kullback–Leibler divergence or relative entropy, is a measure used to quantify the difference between two probability distributions. It is commonly employed in machine learning, data mining, and statistical analysis. As early as 2011, Shiwei Lin proposed using the Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance to evaluate experts’ substantive or normative expertise and assign weights based on the corresponding scores (2011). In comprehensive system decision-making, system attributes have both certain and uncertain characteristics. Uncertain numbers34 are used to characterize or describe data types that contain uncertainty. Based on this, some scholars35,36 proposed that in decision-making problems with uncertain information, mixed attribute values should be converted into binary connection numbers, which are further transformed into two-tuple numbers. Each attribute’s comprehensive weighted symmetric K-L distance is then calculated, primarily using textual data, to provide decision basis, and the effectiveness of this method is verified. In 2023, some scholars proposed a method for assigning weights to indicators based on the uncertain nature of decision-making scheme index values. This method integrates the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance with the mixed attributes of decision-maker preferences37,38. In 2004, other scholars further optimized the model by calculating the comprehensive weighted symmetric K-L distance and the difference between the alternative solution index and the target center. Based on the smaller value of the comprehensive weighted symmetric K-L distance, the optimal alternative solution was selected, better fitting the uncertainty handling in actual decision-making39. This method has been widely applied in fields such as probabilistic risk assessment and decision analysis. However, it has not yet been applied to disaster vulnerability assessment.

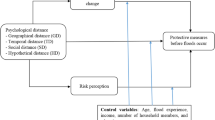

This study determines the index weights through comprehensive symmetric K-L distance optimization and uses ArcGIS 10.7 software to evaluate the flood vulnerability. Based on raster data from 2010, 2015, and 2020, an evaluation index system using the population, economy, and society as frameworks is constructed. The determined and uncertain values of the indicators are then calculated using multi-year indicator data, and the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance between each pair of indicators is computed to obtain the weight results in raster units. Then, a weight map reflecting the spatial variations in the weights is generated. Subsequently, the Ili River Basin is taken as a case study, and a weighted sum model is used to assess the flood vulnerability. This study also applies the entropy weight method to facilitate a comparison with traditional methods. Finally, the evaluation results are analyzed and validated, and reasonable scientific recommendations are provided. The main innovations of this study are twofold: (1) We propose and optimize an enhanced comprehensive symmetric K-L distance weighting method using Python software, making it applicable to grid unit data and realizing the concept of variable weights. (2) This method is applied to a flood vulnerability assessment, where it significantly enhances the accuracy and practicability of the assessment.

Research methods

Optimized comprehensive symmetric Kullback–Leibler (K–L) distance method for determining weights

Interval numbers and transformation

First, let’s introduce the definitions of interval numbers and multi-parameter interval numbers40. In the real number domain R, a specific numerical value range is represented as an interval number, denoted by \(\left[ {x_{1} ,x_{u} } \right]\), where \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{u}\) represent the lower and upper bounds of the interval number, respectively, and satisfy the condition \(0 < x_{1} < x_{u}\). Furthermore, when the interval number range includes one or more specific values within its bounds, it can be extended into a multi-parameter interval number, denoted by \(\left[ {x_{1} ,x_{2} \ldots x_{k} \ldots ,x_{\gamma } } \right]\), where \(x_{k}\) satisfies the condition \(0 < x_{1} < \cdots < x_{k} < \cdots < x_{\gamma } \in R\)37.

The binary connection number combines deterministic and uncertain features extracted from interval numbers and multi-parameter interval numbers, namely, (deterministic, uncertain), which is also an important concept in set pair analysis theory. The binary connection number between the mean \(\overline{x}\) and deviation \(v\) of the interval numbers40,41 is denoted by \(u\left( {\overline{x},v} \right)\). The specific formulas are as follows:

where \(i\) is a special variable that unifies the deterministic and uncertain terms; \(x_{k} \left( {k = 1, \ldots \gamma } \right)\) represents the k-th parameter of the interval number; \(\xi\) denotes the standard deviation of the parameter; and \(\psi\) is the maximum difference between the upper and lower parameter values and the mean. After determining the indicator’s binary connection number using the interval and multi-parameter interval numbers, it can be converted into two-tuple numbers.

Two-tuple numbers and standardization

The Two-tuple numbers are of the form \(\left( {\mu ,\sigma } \right)\), which are further normalized from the Binary connection numbers of mean-deviation values, where the deterministic degree \(\mu\) and uncertain degree \(\sigma\) are determined using formula (6).

Let \(\mu_{st}\) and \(\sigma_{st}\) represent the deterministic and uncertain degree of the binary connection numbers for each index, respectively. Consequently, the two-tuple numbers that can form a raster cell for each index are \(\left( {\mu_{st} ,\sigma_{st} } \right)\), where \(s = 1, \ldots ,n{\text{ and }}t = 1, \ldots ,m\). The binary numbers \(\mu_{st}\) and \(\sigma_{st}\) are obtained according to the normalized formula (7) to yield the deterministic term \(a_{st}\) and uncertain term \(b_{st}\).

Comprehensive symmetric Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance

(1) Comprehensive Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance

Based on the Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance42 and the standardized two-tuple numbers, the comprehensive K-L distance can be calculated35. The K-L divergence is directional in nature. Consider two vectors composed of two-tuple numbers \(S = \left( {\left( {x_{1} ,y_{2} } \right),\left( {x_{2} ,y_{2} } \right), \ldots \left( {x_{m} ,y_{m} } \right)} \right)^{T}\) and \(E = \left( {\left( {p_{1} ,q_{2} } \right),\left( {p_{2} ,q_{2} } \right), \ldots \left( {p_{m} ,q_{m} } \right)} \right)^{T}\) representing the vectors of two indicators at corresponding positions within a grid cell, where \(x_{k} ,y_{k} ,p_{k} ,q_{k} \ge 0,k = 1,2, \ldots m \ge 0\), and \(\left( {x_{k} ,y_{k} } \right)\) and \(\left( {p_{k} ,q_{k} } \right)\) correspond to the standardized two-tuple numbers (deterministic term, uncertainty term) for grid cells \(S\) and \(E\), respectively. The comprehensive K-L divergence of cell \(S\) from \(E\) can be computed using formula (8), where \(\alpha\) is the coefficient representing the deterministic term’s importance in the two-tuple numbers, and \(\beta\) is the coefficient representing the uncertain term’s importance in the two-tuple numbers:

By analogy with formula (8), the comprehensive K-L divergence \(H\left( {E,S} \right)\) of cell \(E\) from \(S\) can be given as formula (9):

(2) Comprehensive symmetric Kullback–Leibler (K-L) distance

\(H\left( {E,S} \right)\) represents the comprehensive K-L distance from \(S\) to \(E\), and \(H\left( {E,S} \right)\) represents the comprehensive K-L distance from \(E\) to \(S\). The comprehensive symmetric K-L distance between \(S\) and \(E\) is obtained by summing these distances, as expressed in Eq. (10):

The comprehensive symmetric K-L distance possesses symmetry, which allows us to conclude that \(D\left( {S,E} \right) = D\left( {E,S} \right)\).

Assessment method

The evaluation model utilized in this study was a weighted summation model that took the grid as its basic unit. This evaluation approach is straightforward, intuitive, and easy to comprehend. It relies on index data normalization and subsequent weight calculations, and produces, to a certain extent, a scientific and commonly employed model in multi-index comprehensive evaluations. First, the linear normalization method used ArcGIS software to normalize each index. Then, ArcGIS software was again leveraged to implement the weighted summation model, as depicted in formula (11):

where \(H_{j}\) represents the index evaluation index;\(w_{i}\) is the index weight of the grid unit; and \(x_{ij}\) is the result of the index after normalization.

The case study

The study area and data sources

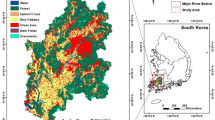

The Ili River Basin is located between the northern (Boluokenu Mountain) and southern (Hark Mountain) branches of the Tianshan Mountains in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China. It spans the geographical coordinates of 74 to 85° E longitude and 42 to 47° N latitude. Encompassing the West Tianshan Mountains and Ili River Valley, the basin covers an area of 60,000 square kilometers. Rich in water, soil, light, and heat resources, it has a catchment area of approximately 57,000 square kilometers, constituting 3.5% of Xinjiang’s total area. With an annual runoff of 15.3 billion cubic meters, the basin is a key potential area for inter-basin water transfer. It is the most contentious basin for cross-border rivers between China and Kazakhstan. The Ili River Basin study area extended beyond the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture to include parts of Hejing County in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture. The Ili River Basin boundary, as designated by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Project Office, is outlined in Fig. 1 below. The basin encompasses various landform types, with overall terrain trends that are high in the east and low in the west and narrow in the east and wide in the west. This can be succinctly summarized as “two mountains enclosing a basin”43. The Ili River Basin experiences a continental temperate climate with relatively abundant precipitation, although its spatial and temporal distributions are highly uneven. The Ili River Valley opens westward and is flanked by mountains on three sides, making it particularly susceptible to snowmelt-induced floods on both valley sides. The abundant precipitation in spring, along with frequent thunderstorms and hailstorms in the mountainous regions during summer, elevates the risks of floods and waterlogging disasters. Additionally, human activities, such as excessive reclamation and vegetation destruction, have exacerbated the soil erosion and reduced the river’s flood control capacity. Together, these factors pose significant challenges to flood and waterlogging disaster management in the Ili River Basin.

(a) Map of China, with map review number: GS(2024)0650 (b) Administrative division map of Xinjiang (c) Overview map of the study area. These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

The data used for the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability assessment were primarily categorized into three types: basic geographic data, remote sensing image data, and statistical data. The basic geographic data were sourced from various organizations, including the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program Office, Geospatial Data Cloud, and National Catalog Service for Geographic Information Resources. The remote sensing image data were obtained from the Global Soil Coverage Database and Earth Resource Data Cloud Platform. Lastly, the statistical data were compiled from sources such as the County Statistical Yearbook of China and Sixth and Seventh Population Censuses of China.

Constructing an evaluation index system

Some scholars8 argue that the evaluation indicators of regional disaster-bearing vulnerability primarily focus on social indicators, with the impact scope extending to the population, disaster-affected areas, and major economic factors. In contrast, other scholars44,45 categorized disaster-bearing vulnerability assessment into two levels: natural vulnerability (or physical vulnerability) and social vulnerability, or into three dimensions: population, socio-economy, and environment. Drawing on these scholars’ research and considering the study area’s unique characteristics, this study established a first-level indicator system that comprised population vulnerability, economic vulnerability, and social vulnerability. Furthermore, based on additional research46 and the specific characteristics of the study area, 20 secondary indicators were selected. The population vulnerability included the following: population density (PD), female population (FP), sex ratio (MYS), and demographic share of the elderly and young (PSE). The main reason for selecting the female population as an indicator, which covers population density, quantity, and structure, is that women are more vulnerable to disasters and are more prone to risks. Economic vulnerability encompasses the economic benefits, structure, total output, and development potential. Specifically, the economic vulnerability indicators include the gross domestic product (GDP), POI density (POI), primary industry value added (PIV), secondary industry value added (SIV), year-end main livestock and poultry inventory (LVEI), total meat production (TMP), total grain production (TGP), and the number of industrial enterprises above a designated size (NLIE). These indicators comprehensively reflect the stability and resilience of a region’s economy. Social vulnerability indicators reflect the social structure, service level, and environmental adaptability. Specifically, the fractional vegetation cover (FVC), bed capacity in medical and health facilities (MBN), average years of schooling (RD), number of primary school students (RYD), road density (UR), railway density (LUT), urbanization rate (SR), and land-use type (EJPR) are considered.

Based on the selected 20 indicators, a correlation analysis was conducted, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. The analysis revealed that the population density was highly correlated with the GDP, POI density, road density, and railway density. This was consistent with the actual situation, as densely populated areas with well-developed infrastructure and transportation networks drive economic activity. The secondary industry value added showed a high correlation of 0.86 with the number of industrial enterprises above a certain size, both of which reflected the economic development level. Due to the high degree of redundancy between these two indicators, this study excluded the number of industrial enterprises above a certain size and retained the secondary industry value added, as the latter better represents the overall economic impact rather than merely the number of individual enterprises. Furthermore, there was a high correlation of 0.88 between the number of hospital beds in medical and health institutions and the number of primary school students. Both indicators reflect disaster prevention and mitigation capabilities; however, medical facilities are deemed more appropriate for this purpose than the number of students. Consequently, the number of primary school students was excluded. As a result, 18 indicators were selected to construct the flood vulnerability assessment indicator system (Table 1).

Weight determination

Determining the weights using an optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance

This study assessed the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability using data from 2010, 2015, and 2020. The three-year data for each indicator were treated as interval data to calculate each indicator’s comprehensive symmetric K-L distance. During the data processing, textual statistical yearbook data were converted into raster data and combined with spatial attribute auxiliary data, such as the population distribution and landform. This approach not only enhanced the spatial resolution and accuracy of the raster data but also improved its spatial expression and analytical value. This process fully accounted for spatial heterogeneity to ensure that each raster cell’s value accurately reflected the data’s spatial variability. Furthermore, an in-depth analysis was conducted on the data resolution’s impact on the results. The analysis revealed that as the resolution increased, the spatial data distribution could be depicted more precisely; however, this also introduced challenges related to the computational complexity and data volume. Therefore, when selecting the raster cell size, it was necessary to balance the computational efficiency with the need to capture data details. This study selected a 30 × 30 m resolution as a compromise. Furthermore, the land-use type data were reclassified and assigned values according to the standard47 as follows: farmland (0.2), forest (0.1), shrub (0.1), grassland (0.1), water area (0.5), snow and ice (0.1), bare land (0.3), impervious surface (1), and wetland (0.1). Grid data, including the population density, GDP, POI density, vegetation coverage, and land-use types, were uniformly processed through operations, such as clipping. After the data preprocessing, the three-year grid data for each indicator were input into Python software. Following formulas (1)–(7), all the indicators were processed to obtain each indicator’s deterministic and uncertain terms. Subsequently, these two datasets were utilized to calculate the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance for each indicator based on formulas (8)–(10). The resulting comprehensive symmetric K-L distances for each indicator were then normalized using ArcGIS software, and the normalized comprehensive symmetric K-L distances served as the weight data for each indicator. ArcGIS software was further employed to visualize the weight data for the analysis. In this study, the importance ratio coefficients α and β in Eqs. (8) and (9) were set to 1 since the deterministic and uncertain terms were considered equally important. Figure 3 presents a flowchart of the key steps taken when optimizing the comprehensive symmetric K-L divergence to determine the weights, illustrating the process of deriving the comprehensive symmetric K-L divergence for each indicator from each indicator’s deterministic and uncertain grid data.

The comprehensive K-L distance between each pair of indicators was calculated, and the sum of these distances was then used to obtain the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance for each indicator. The final normalized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance served as the weight, which reflected the complex interactions and influence relationships between the various indicators. Figures 4 through 6 display the weight distribution maps for each indicator, as obtained through the optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance weighting method.

(a) Population density weight distribution map (b) Female population weight distribution map (c) Sex ratio weight distribution map(d) Demographic share of the elderly and young weight distribution map (e) GDP weight distribution map (f) POI Density weight distribution map.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Specifically, Fig. 4a illustrates the weight results derived from calculating the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance between the population density and the other indicators. The results show a general increase in weight from the southeast to the northwest, with the highest weights found in Khorgos, followed closely by Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County. These results were primarily driven by the comprehensive calculations that involved other indicators. Similarly, Fig. 4b presents the weight results for the female population, revealing that the regions with the highest weights were Zhaosu County, followed by Yining City, Yining County, and Nilka County, while Qorghas exhibited the lowest weight. Notably, the weight values in Yining County varied across different regions due to the comprehensive calculations with other indicators. Figure 4c shows the gender ratio weight distribution map. The results indicate that the Ili River Basin’s eastern region exhibited lower weights, while the northern and some southwestern areas showed medium weights. The highest gender ratio weight values were concentrated in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County. Figure 4d presents the weight distribution map for the demographic share of the elderly and young, where various weight levels were observed across the region, with the highest values located in Khorgos and Cocodala City. Figure 4e displays the GDP indicator weight results, where Tekes County and Nilka County showed both high and low weight distributions, reflecting the variable weights concept. Finally, Fig. 4f illustrates the POI density weight results, where regions with a higher POI density exhibited higher weight values, indicating a clear correlation between the POI density and the weight distribution.

The following weight results are demonstrated in Fig. 5: (a) The added value of the primary industry. Similar to the GDP indicator, the weight distribution varied significantly across the regions. For instance, Nilka County, Xinyuan County, Hejing County, and Tekes County exhibited areas with high weight values. (b) The secondary industry added value. Regions with higher weight values were concentrated in Zhaosu County, Cocodala City, Yining City, Gongliu County, and parts of the southern region of Tekes County, effectively demonstrating the variable weights concept. (c) The end-of-year number of livestock and poultry. Qorghas and Gongliu County showed higher weights, while lower weights were observed in regions such as Zhaosu County, Xinyuan County, and Yining County. (d) The total meat production. Higher weight values were found in Khorgas and Hejing County, while Tekes County exhibited medium weight values and other regions had lower weights. The weight distribution for this indicator varied across counties and cities due to the system complexity. (e) The total grain output. High-weight regions were like those for the total meat production, with medium-weight values primarily found in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County. The boundary between the high and low weight values in Hejing County was distinct due to the comprehensive calculations of various indicators. (f) The average years of education. The southwestern regions exhibited lower weights, while the eastern regions and Qorghas in the northwest showed higher weights, reflecting the concept of spatially varying weight distributions.

(a) Primary industry value added weight distribution map (b) Secondary industry value added weight distribution map (c) Year-end inventory of main livestock and poultry weight distribution map (d) Total meat production weight distribution map (e) Total grain output weight distribution map (f) Average years of schooling weight distribution map.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

The following weight results are demonstrated in Fig. 6: (a) The vegetation coverage. These results effectively reflect the variable weights concept, with each region receiving different weight values based on this indicator’s objective data and the combined influence of other indicators. (b) The number of hospital beds in medical and health institutions. The Ili River Basin’s central area showed lower weights, and the values increased as they spread outward. Higher weight values were found in the northern parts of Khorgas and Qorghas. (c) The road density. The weight values were primarily influenced by this indicator itself, with higher road density areas corresponding to higher weight values. (d) The railway density. Regions with higher weight values were predominantly located in areas with a greater railway density. (e) The urbanization rate. This indicator was significantly influenced by other factors. The Ili River Basin’s western region showed lower weight values, while Yining City and Yining County had higher values. (f) The land-use types. This indicator’s weight distribution was mainly driven by the objective data, which resulted in various weight values across regions.

(a) FVC weight distribution map (b) Bed capacity in medical and health facilities weight distribution map (c) Road density weight distribution map (d) Railway density weight distribution map (e) Urbanization rate weight distribution map (f) Land use type weight distribution map.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Determining the missing weights using the entropy weight method

For the comparative analysis, this study also employed the traditional objective weighting method, namely, the entropy weight method, to calculate the weights of various flood vulnerability indicators for the Ili River Basin. The specific formula was from the methodology outlined by Chen48. First, ArcGIS software was used to conduct the zonal statistical analysis for each indicator’s raster data, using counties and cities as boundaries. The final weight results for each indicator are shown in Fig. 7. Among these, the POI density held the largest weight proportion at 0.22715, followed by the population density (0.14993), railway density (0.14406), and the end-of-year number of livestock and poultry (0.14881). Other indicators exhibited smaller weight proportions, such as the road density (0.08475), GDP (0.04001), primary industry value added (0.03801), and secondary industry value added (0.03256). Indicators such as the demographic share of the elderly and young (0.03555), fractional vegetation cover (0.02499), total meat production (0.01602), total grain production (0.01481), land-use type (0.01401), and female population (0.01081) had lower weights. Some indicators, including the urbanization rate (0.00926), sex ratio (0.00404), average years of schooling (0.00447), and number of beds in medical and health institutions (0.00075), were assigned very small weight values. While the traditional entropy weight method assigns weight values to each indicator, it fails to account for the system’s complexity, the correlations between indicators, or the concept of variable weights.

Results and analysis

In ArcGIS, we first calculated the average values for each indicator using data from three years. Subsequently, the indicators were normalized using the min–max normalization method49 to obtain the normalized data for each indicator. Next, the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability was assessed using the weighted sum model (Eq. 11), which incorporated the indicator weights determined using the optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance method. A similar vulnerability assessment was also conducted using the weighted sum model based on the indicator weights derived from the entropy weight method. Finally, the vulnerability results were classified into five levels—low, lower, medium, higher, and high—using the natural breaks classification method in ArcGIS to present the assessment outcomes visually. Figures 8, 9, 11, and 12 display the vulnerability comparison results obtained using the two different weighting methods; in each of these figures, (a) shows the vulnerability results based on weights determined using the optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance method, while (b) displays the results based on weights determined using the entropy weight method.

(a) Vulnerability results based on optimized symmetric K-L Distance weights (b) Vulnerability results based on entropy weight method.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

(a) Economic vulnerability results based on optimized symmetric K-L distance weights (b) Economic vulnerability results based on entropy weight method.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Population vulnerability assessment results

As a key disaster-bearing entity in flood events, the population is directly linked to vulnerability through its density. Areas with a higher population density face greater flood risks because more people are exposed to potential hazards, which can result in higher casualties and economic losses. Additionally, population growth and concentration often correlate with economic development, which, while enhancing disaster resilience, also increases the potential impact of disasters, as economically developed regions may suffer more severe economic losses when disasters strike. Moreover, changes in the population structure, such as an aging population, can further heighten a region’s vulnerability.

Therefore, when conducting flood vulnerability assessments, it is essential to consider multiple factors, including the population density, population structure, and population size. Figure 8 presents a comparative diagram of the population vulnerability spatial distribution. Figure 8a shows the results based on the weighting method proposed in this paper. Overall, the vulnerability levels were higher in the northwest and southeast, and lower in the southwest and northeast. The population vulnerability levels in Yining City, Khorgos City, and Cocodala City fell into the higher and highest categories. This outcome was primarily influenced by the population density and proportion of the elderly and children. These two indicators had higher weight values in these areas compared with the other regions. The lower and medium vulnerability levels were mainly concentrated in the eastern part of the basin. Additionally, the significant difference in the population vulnerability distribution within Tekes County highlights the importance of variable weights. Figure 8b shows the results obtained using the traditional entropy weight method to determine the weights. It is evident that the population vulnerability distribution levels mirrored the population density distribution, with the population density being the primary influencing factor. The population density weight (0.14993) was significantly higher than that of the other three population indicators, which resulted in an uneven weight distribution that failed to capture the comprehensive impact of all the indicators. Consequently, the results disproportionately favored the indicators with higher weights. For the population indicators, it is important to consider not only the population density and quantity but also the population structure. This highlights the entropy weight method’s limitations, as it neglects the roles of other factors, such as the gender ratio and demographic share of the elderly and young.

Economic vulnerability assessment results

Figure 9 presents a comparison of the economic vulnerability assessment results, revealing significant differences. Figure 9a considers the comprehensive impacts of multiple indicators, which led to varying weight allocations and, consequently, diverse economic vulnerability level distributions. Higher vulnerability levels were primarily concentrated in some southwestern and small northwestern regions, which could be largely influenced by the GDP, primary industry added value, and secondary industry added value. Moderate and lower vulnerability levels were more evenly distributed throughout the Ili River Basin, reflecting a comprehensive consideration of economic vulnerability at the grid-cell level. In contrast, Fig. 9b shows a more extensive high-vulnerability area compared with Fig. 9a, which was primarily influenced by the POI indicator alone. Moderate vulnerability areas were concentrated in the central parts of Hexing County, Zhaosu County, and Xinyuan County. Lower vulnerability levels were mostly found in Tekes County and Gongliu County, while Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County, Yining County, and Nilka County showed primarily lower vulnerability levels. It is evident that the distribution of economic vulnerability levels in Figure (b) closely followed the county boundaries, with high-vulnerability areas being influenced by a single indicator.

Furthermore, we also conducted a spatial correlation analysis to elucidate the relationships between different indicators and their associations with economic vulnerability (Fig. 10). Based on the previous indicator correlation analysis, it was evident that the correlations between the GDP and the primary and secondary industry added values were not strong, indicating that these indicators were not redundant and each contributed to the overall dataset diversity. Additionally, univariate correlation analyses50,51 were conducted between the GDP, primary industry added value, and economic vulnerability results. The statistical analysis revealed that in Fig. 10a the correlation coefficients between the economic vulnerability and the GDP ranged from -0.3 to 0.9, with a spatial average of 0.69. Similarly, in Fig. 10b, the correlation coefficients between the economic vulnerability and the primary industry added value ranged from -0.27 to 0.93, with a spatial average of 0.66. Both indicators showed an overall positive correlation with economic vulnerability. The areas where the economic vulnerability was positively correlated with the GDP and primary industry added value accounted for 83% and 71% of the total basin area, respectively. Therefore, the GDP demonstrated a stronger correlation with the economic vulnerability, and both indicators were key factors that influenced the economic vulnerability.

(a) Correlation map of economic vulnerability and GDP (b) Correlation map of economic vulnerability and primary industry value-added. These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Social vulnerability assessment results

Figure 11 presents a comparison of the social vulnerability assessment results, where it is evident that the levels in Fig. 11a are more nuanced compared with Fig. 11b. In Fig. 11a, due to the influence of indicator weight distribution, the grading is not distinctly visible, reflecting the variable weights concept. This figure demonstrates that areas rated above the medium level were spread across several counties and cities within the entire basin, which aligned with the flexible variations in actual conditions. The weight distributions of the vegetation coverage and land-use type among the social vulnerability indicators were less clearly delineated due to their inherent data characteristics. As a result, the social vulnerability grading under these indicators’ influences was also less prominent. Additionally, the highest-rated areas were primarily located in the central regions of Yining County and Yining City, predominantly influenced by the railway density indicator. In Fig. 11b, the regions with medium and higher vulnerability levels were mainly those with a higher railway density, as the railway density weight derived from the entropy weight method was relatively high at 0.14406. Furthermore, the areas classified as having high social vulnerability in Fig. 11a corresponded with those in Fig. 11b, reflecting the significant role of the railway density indicator in the social vulnerability assessments. Additionally, the medium-vulnerability-level areas in Fig. 11b exhibited a block-like pattern, which aligned with the county- and city-level results and further influenced the social vulnerability level distribution.

(a) Social vulnerability results based on optimized symmetric K-L distance weights (b) Social vulnerability results based on entropy weight method.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Vulnerability assessment results and verification of flood

Figure 12 presents the flood vulnerability assessment results for the Ili River Basin, where it is evident that the variable weight method adopted in this study, which determines weights based on grid units, differs from traditional weighting methods. The comparative analysis demonstrated that both methods showed a similar trend in the vulnerability level distributions, with the overall pattern indicating higher vulnerability in the northwest compared with the southeast. Lower vulnerability levels were concentrated in the mountainous areas surrounding the basin.

(a) Flood disaster vulnerability results based on optimized symmetric K-L distance weights (b) Flood disaster vulnerability results based on entropy weight method.These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Figure 12a shows that high-grade areas were primarily concentrated in parts of Yining City, Qorghas, and Khorgas, which were heavily influenced by the social vulnerability factors. These higher-grade areas were scattered throughout the basin, reflecting all the indicators’ combined impact and respective weights. The medium-grade areas were mainly found in the basin’s southwestern, southeastern, and northwestern parts. The lower-grade areas were predominantly located in the central region, which showed a diverse distribution with varied risk levels across different counties and cities. The lowest-grade areas were mostly in the higher-elevation mountainous regions. Figure 12b shows that the distribution units were larger and primarily followed the boundaries of counties and cities. Areas with vulnerability grades above medium were more widespread than in Fig. 12a, where they covered Khorgas, Qorghas, Yining City, Cocodala City, Zhaosu County, Hejing County, and most of the central region of Xinyuan County, with isolated points in the central part of the basin. The distribution of regions with vulnerability grades below medium was like that in Fig. 12a, but the areas with the lowest grades were more extensive.

The assessment results show more pronounced regional differences, particularly in identifying high-vulnerability areas. The method proposed in this study could more accurately pinpoint critical regions, which demonstrated its higher sensitivity in capturing the regional vulnerability characteristics. In contrast, the traditional methods tended to produce excessively high grades that may not have aligned with actual conditions.

Taking Khorgas and Qorghas as specific examples for the analysis, there was a clear variation in the vulnerability grades between these two areas. Figure 12a shows that the vulnerability grade distribution in Khorgas had clear distinctions between the medium and high grades. However, in Fig. 12b, the entire region of Khorgas was classified as a high grade, which may not accurately reflect the actual situation. Similarly, the vulnerability distribution in Qorghas was comparable with that of Khorgas. Figure 12a shows that most areas of Qorghas fell into the medium-grade vulnerability category, while some southeastern parts were classified as a lower grade. This classification was primarily influenced by the weight distribution of five indicators: population density, female population, primary industry added value, secondary industry added value, and total meat production. The higher-grade areas were mostly concentrated in the southern parts of Qorghas. These results demonstrate that the optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance weighting method proposed in this study was highly applicable for the flood vulnerability assessments since the outcomes were scientifically sound and detailed, and the method successfully implemented true variable weighting.

Furthermore, to identify the key factors that influenced the flood vulnerability assessment results, this study employed the Extended Fourier Amplitude Sensitivity Test (EFAST) method52 for the sensitivity analysis. To construct bar chart in Fig. 13, we quantified the influence of each indicator on the assessment results. The analysis revealed that the population density (PD) was ranked first, with a sensitivity coefficient close to 0.2, indicating its significant impact on the results. Closely following were the female population (FP), main livestock and poultry year-end inventory (LVEI), and bed capacity in medical and health facilities (MBN), all with sensitivity coefficients that exceeded 0.1. This suggests that the economic activities and society’s disaster resilience also played crucial roles. Additionally, the GDP sensitivity coefficient was relatively high, where it exceeded 0.05. Notably, the indicators with higher sensitivity coefficients were directly associated with the population, economy, and social capacity, reflecting their comprehensive influence on the vulnerability outcomes.

The assessment results verification process evaluated the reliability of the identified high-risk and low-risk areas using additional data and thus assessed the flood vulnerability assessment accuracy53. It is widely acknowledged that areas with dense residential settlements and urban infrastructure typically exhibit higher vulnerability54. In this study, the POI (point of interest) data spatial distribution was used to validate the final vulnerability outcomes. POIs, which include public utilities, transportation hubs, accommodation facilities, and key infrastructure, represent economic zones and serve as significant disaster-bearing entities. Figure 14a illustrates the POI spatial distribution in the Ili River Basin, with a notable concentration in parts of Yining City, Yining County, and Cocodala City. This distribution pattern closely aligned with the main river systems within the Ili River Basin. Figure 14b shows the proportion of POIs across different vulnerability levels. The calculations revealed that over half of the POIs were located in high-vulnerability areas, where they specifically accounted for 65.5%. The POI proportions in the medium and higher vulnerability levels were approximately 30.3%, while the lowest vulnerability levels contained the fewest POIs. Additionally, this study examined the historical flood events in Yining County, including the torrential rain and flooding that occurred on July 5, 2012. This event breached the flood defenses in multiple townships, which caused water to inundate several villages and damage multiple electrical facilities. The disaster affected 661 people, where water entered the courtyards of 301 households and 96 basements across three residential areas. Another significant event occurred in May 2016, when floods triggered by heavy rainfall impacted several townships in Yining County. This flooding resulted in water entering villages and damaging several county–township roads. The flood breached over 150 m of flood defenses in the township and more than 100 m of rural roads. These events illustrate that Yining County experienced significant historical flood impacts, which indirectly validated the flood vulnerability assessment results. The POI location verification and the historical disaster events aligned with the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability assessment results, which further confirmed the assessment accuracy.

(a) Spatial Distribution of POI Overlayed with Flood Disaster Vulnerability Results (b) Proportion of POI in Different Vulnerability Levels. These maps were processed and generated in ArcGIS 10.7 software (URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index).

Conclusions and suggestions

Based on the comprehensive symmetric K-L distance method for determining weights, this study introduced an innovative optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance weighting method. This method utilizes grid cells as the fundamental research units, enhancing the weight determination’s accuracy and rationality. It also fully embodies the variable weights concept, making the weight allocation process more flexible and adaptable to varying conditions. This optimization provides a robust foundation for future research, particularly in addressing complex and dynamic natural and social phenomena, such as climate change. By precisely quantifying the differences and correlations between individual grid cells, this method enables researchers to better understand the spatial distribution, trends, and impacts of climate change, offering a solid scientific basis for devising effective response strategies and mitigation measures. Furthermore, this method’s flexibility and adaptability suggest its potential applicability across a wide range of research fields, contributing to advancements in related disciplines. In this study, this method was applied to assess the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability, where the following key conclusions were made:

-

(1)

The optimized comprehensive symmetric K-L distance weighting method proposed in this study utilizes grid units to assign weights to each indicator. This method accurately reflects the variable weighting concept, as it allows the weights to vary across different spatial units, thereby capturing the spatial heterogeneity of vulnerability. When applied to the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability assessment, this method demonstrated strong applicability and thus offered a flexible and scientifically sound approach to index weighting. The results validated its effectiveness in producing more precise and contextually relevant disaster vulnerability assessments.

-

(2)

The population vulnerability assessment for the Ili River Basin revealed that areas with higher vulnerability levels were predominantly concentrated in the northwestern regions, including parts of Khorgos City, Yining City, and Cocodala City. These areas were primarily influenced by the population density and proportion of elderly and child populations. The economic vulnerability, on the other hand, exhibited more spatial variability, with higher vulnerability levels concentrated in certain southwestern regions and a small portion of the northwestern areas. This distribution was largely driven by factors such as the GDP, primary industry added value, and secondary industry added value. The social vulnerability assessment indicates that the areas with medium and high vulnerability levels were distributed across various counties and cities throughout the basin, largely influenced by the vegetation coverage and land-use types. Notably, high vulnerability levels were observed in parts of Yining County and Yining City, where the railway density played a significant role.

-

(3)

The Ili River Basin flood vulnerability levels indicate that the northwestern, southwestern, and southeastern regions predominantly exhibited medium to high vulnerability levels. In contrast, the southern and northeastern regions generally displayed lower vulnerability levels. Notably, areas such as Yining City, Yining County, and Cocodala City were characterized by the highest vulnerability levels, which were primarily driven by the social vulnerability factors.

To reduce the Ili River Basin flood vulnerability, the following suggestions are proposed based on the conclusions drawn in this study:

-

(1)

It is essential to strategically plan the urban spatial layout of Yining City and Cocodala City to reduce the urban density and lower the overall urban vulnerability. Additionally, efforts should be made to enhance the healthcare and educational infrastructure in Yining County, Xinyuan County, and other vulnerable areas. Strengthening the public awareness of disaster prevention and mitigation through education and outreach is also crucial to improving community resilience against future floods.

-

(2)

Strengthen the construction of fundamental flood control projects in the Ili River Basin, encompassing reservoirs, river channels, and embankments, while reinforcing lifeline engineering. Enhance the flood warning and monitoring capabilities, as well as improving the public awareness, warning systems, and emergency response capabilities. Formulate comprehensive policies, refine flood prevention emergency response plans, and establish robust emergency management systems for flood control and drainage in grassroots units and communities.

-

(3)

Strengthen the community-level participation and public-awareness-raising activities by organizing regular disaster prevention and mitigation training sessions and drills. These activities aim to elevate the public awareness of flood risks and cultivate self-rescue and mutual-rescue capabilities among community members. Furthermore, they enhance community resilience and encourage sustained public participation in this regard.

Data availability

The basic geographic data used in this study is available at: http://gis5g.com/data/tdly, The remote sensing image data used in this study is available at: https://www.gscloud.cn/.

References

Zhou, J., Zhang, H., Wang, B. & Sun, Q. Spatiotemporal characteristics analysis of vulnerability to urban rainstorm and flood disasters. Geospatial Inf. 19, 40–43 (2021).

Ji, K., Li, X., Gao, J., Xu, J. & Gao, Y. Assessment of urban vulnerability to heavy rain and flood disasters. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 44, 13–20 (2024).

Diriba, D., Takele, T., Karuppannan, S. & Husein, M. Flood hazard analysis and risk assessment using remote sensing, GIS, and AHP techniques: A case study of the Gidabo Watershed, main Ethiopian Rift, Ethiopia. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2024.2361813 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Urban flood risk assessment based on DBSCAN and K-means clustering algorithm. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2023.2250527 (2023).

Shi, P. Theory and practice on disaster system in a fourth time. J. Nat. Disasters 1–7 (2005).

Mwalwimba, I. K., Manda, M. & Ngongondo, C. Flood vulnerability assessment in rural and urban informal settlements: Case study of Karonga District and Lilongwe City in Malawi. Nat. Hazards 120, 10141–10184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-024-06601-5 (2024).

Gao, C., Zhang, Z., Liu, Q. & Ruan, T. Study on the optimal grid method in assessment of vulnerability to floods disaster—A case study in the mainstream of Huaihe River Basin. J. Nat. Disasters 27, 119–129 (2018).

Fan, Y. X., Luo, Y. & Chen, Q. S. Research on indexes system about regional vulnerability assessment. Geoscience 113–116 (2001).

Sun, N. et al. Urban flooding risk assessment based on FAHP–EWM combination weighting: a case study of Beijing. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2023.2240943 (2023).

Ziwei, L. et al. GIS-based risk assessment of flood disaster in the Lijiang River Basin. Sci. Rep. 13, 6160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32829-5 (2023).

Wang, X., Chen, W., Yin, J., Wang, L. & Guo, H. Risk assessment of flood disasters in the Poyang lake area. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 100, 104208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.104208 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Disaster mapping and assessment of Pakistan’s 2022 mega-flood based on multi-source data-driven approach. Nat. Hazards 120, 3447–3466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.104208 (2024).

Nguyen, T. L., Asahi, C., Tran, T. A. & Le, N. H. Indicator-based approach for flood vulnerability assessment in ancient heritage city of Hoi An, Central Region of Vietnam. Nat. Hazards 114, 2357–2385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05475-9 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Natural hazard triggered technological risks in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sci. Rep. 11, 13842. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93353-y (2021).

Wang, X., Xia, J., Dong, B., Li, Q. & Zhang, X. Hydrodynamics-based assessment of flood losses in an urban district under changing environments. Nat. Hazards https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-024-06792-x (2024).

Mustafa, A., Szydłowski, M., Veysipanah, M. & Hameed, H. M. GIS-based hydrodynamic modeling for urban flood mitigation in fast-growing regions: A case study of Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Sci. Rep. 13, 8935. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36138-9 (2023).

Wehbe, C. & Baroud, H. Limitations and considerations of using composite indicators to measure vulnerability to natural hazards. Sci. Rep. 14, 19333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68060-z (2024).

Liu, Q. Y. & Wu, X. N. Review on the weighting methods of indexes in the multi-factor evaluation. Knowl. Manag. Forum 2, 500–510 (2017).

Khan, A., Gong, Z., Shah, A. A. & Haq, M. A comprehensive assessment model for livelihood vulnerability using fuzzy TOPSIS technique: A case of 2022 flood in Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 103, 104351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104351 (2024).

Chai, L. et al. Risk assessment of land subsidence based on GIS in the Yongqiao area, Suzhou City, China. Sci. Rep. 14, 11377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62108-w (2024).

Zheng, Q., Lyu, H.-M., Zhou, A. & Shen, S.-L. Risk assessment of geohazards along Cheng-Kun railway using fuzzy AHP incorporated into GIS. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 12, 1508–1531. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2021.1933614 (2021).

Ren, D. F., Wei, X., Wang, J. L. & Wang, F. Y. Urban waterlogging risk assessment from the perspective of the optimal scale transformation-analytic hierarchy process. J. China Hydrol. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.19797/j.cnki.1000-0852.20230324 (2024).

Sun, H., Zha, Z., Huang, C. & Yang, X. Flood disaster industry-linked economic impact and risk assessment: A case study of Yangtze River Economic Zone. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04556-y (2024).

Senan, C. P. C. et al. Flood vulnerability of a few areas in the foothills of the Western Ghats: A comparison of AHP and F-AHP models. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 37, 527–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-022-02267-2 (2023).

Gorgij, A. D., Kisi, O., Moghaddam, A. A. & Taghipour, A. Groundwater quality ranking for drinking purposes, using the entropy method and the spatial autocorrelation index. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-6589-6 (2017).

Yousefi, S. et al. Assessing the susceptibility of schools to flood events in Iran. Sci. Rep. 10, 18114. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75291-3 (2020).

Wang, D. Y., Zhang, L. D. & Wu, Q. Urban storm flood disaster risk assessment based on social media data—A case study of the “7.20” rainstorm event in Zhengzhou City. Saf. Environ. Eng. 31, 11–22 (2024).

Cao, X. et al. Coastal erosion and flooding risk assessment based on grid scale: A case study of six coastal metropolitan areas. Sci. Total Environ. 946, 174393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174393 (2024).

Ma, S. Q., Lyu, S. & Zhang, Y. Weighted clustering-based risk assessment on urban rainstorm and flood disaster. Urban Clim. 39, 100974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100974 (2021).

Sammonds, P., Alam, A., Day, S., Stavrianaki, K. & Kelman, I. Hurricane risk assessment in a multi-hazard context for Dominica in the Caribbean. Sci. Rep. 13, 20565. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47527-5 (2023).

Wang, G. & Shao, Q. Design of a smart medical service quality evaluation system based on a hybrid multi-criteria decision model. Sci. Rep. 14, 26407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71224-6 (2024).

Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Li, H., Wang, G. & Ai, J. An adaptive operation planning and EBO-BPNN optimization method for decision support systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 21838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72808-y (2024).

Shu, B., Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & Zhang, Q. Scenario simulation of urban land expansion integrate variable weight with constrained fuzzy cellular automata. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 38, 498–503 (2013).

Liu, D., Jiang, Q., Zhu, H. & Huang, B. Distributing UAVs as wireless repeaters in disaster relief via group role assignment. Int. J. Coop. Inf. Syst. 29, 2040002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021884302040002X (2020).

Ma, J. Generalized grey target decision method for mixed attributes based on Kullback-Leibler distance. Entropy 20, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/e20070523 (2018).

Ma, J. S., Ma, X., Yue, J. & Tian, D. Kullback-Leibler distance based generalized grey target decision method with index and weight both containing mixed attribute values. IEEE Access 8, 162847–162854 (2020).

Ma, J. S. A determination method of objective weights for mixed attribute decisions based on symmetric K-L distances and decision makers’ subjective preferences. Ind. Eng. J. 26, 62–69 (2023).

Lin, S.-W. Jackknife evaluation of uncertainty judgments aggregated by the Kullback-Leibler distance. Appl. Math. Comput. 218, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2011.05.087 (2011).

Ma, J. & Zhu, H. Symmetric Kullback-Leibler distance based generalized grey target decision method for mixed attributes. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 14, 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1108/GS-01-2024-0001 (2024).

Zeng, Y. & Zhang, R. Energy-efficient UAV communication with trajectory optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 16, 3747–3760 (2017).

Zhao, K. Q. Decision making algorithm based on set pair analysis for use when facing multiple uncertain attribute. CAAI Trans. Intell. Syst. 5, 41–50 (2010).

Kullback, S. & Leibler, R. A. On information and sufficiency. Ann. Math. Stat. 22, 79–86 (1951).

Momin, G., Yang, L. M., Liu, Y. & Li, X. G. Spatial and temporal distribution of flood disasters and characteristics of disaster-pregnant environment in Yili River Basin in recent 30 years. Arid Land Geogr. 1–17 (2024).

Xu, W., Liu, K., Li, B. X., Du, J. & Wang, M. Vulnerability assessment of disaster-bearing bodies in multi-hazardous major natural disasters: Indicators, methods, and results. Disaster Reduct. China 16–18 (2022).

Xu, Z. X., Tang, Q. Z., Chen, H. & Yang, F. Assessment on the vulnerability of urban hazard bearing body based on refined spatial patterns. Adv. Water Sci. 35, 38–47 (2024).

Zhang, B., Zhao, Q. S. & Jang, Y. J. Research on indexes system about regional vulnerability of hazard-affected bodies and fine spatial quantitative model. J. Catastrophol. 25, 36–40 (2010).

National Technical Committee 283 on Ocean of Standardization Administration of China. Technical guidelines for risk assessment and zoning of marine disaster Part 1: Storm surge (2019).

Chen, P. On the diversity-based weighting method for risk assessment and decision-making about natural hazards. Entropy 21, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21030269 (2019).

Moreira, L. L., de Brito, M. M. & Kobiyama, M. Effects of different normalization, aggregation, and classification methods on the construction of flood vulnerability indexes. Water 13, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010098 (2021).

Bi, S., Bie, S., Hu, X. & Zhang, H. Analysis on the characteristics of spatio-temporal evolution and aggregation trend of early COVID-19 in mainland China. Sci. Rep. 12, 4380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08403-w (2022).

Zhang, L., Hou, Q., Duan, Y. & Liu, W. Spatial correlation between water resources and rural settlements in the Yanhe Watershed based on bivariate spatial autocorrelation methods. Land 12, 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091719 (2023).

Li, Z. H., Jin, X. L., Liu, H. L., Xu, X. G. & Wang, J. H. Global sensitivity analysis of wheat grain yield and quality and the related process variables from the DSSAT-CERES model based on the extended Fourier Amplitude Sensitivity Test method. J. Integr. Agric. 18, 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(18)62046-5 (2019).

Jiang, W., Deng, L., Chen, L., Wu, J. & Li, J. Risk assessment and validation of flood disaster based on fuzzy mathematics. Prog. Nat. Sci. 19, 1419–1425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.12.010 (2009).

Bathrellos, G. D., Skilodimou, H. D., Chousianitis, K., Youssef, A. M. & Pradhan, B. Suitability estimation for urban development using multi-hazard assessment map. Sci. Total Environ. 575, 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.025 (2017).

Funding

This research was supported by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No.2022xjkk0600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.: Helps to review the overall framework and main content of the article. Y.L.: Has made contributions to data processing, method construction, result analysis, and paper writing. X.Y.: Contributed to data collection and preprocessing. X.L.: Contributed to the formatting and layout of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Li, Y., Yuan, X. et al. Flood vulnerability assessment in the Ili River Basin based on the comprehensive symmetric Kullback–Leibler distance. Sci Rep 15, 7420 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90078-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90078-0