Abstract

Latin Americans are underrepresented in the current equations used to estimate glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and the applicability of their predictions to this population may therefore be questionable. The objective of this study was to develop a new equation to estimate GFR based on data from Argentina. A cross-sectional study was conducted. We included 583 Argentinian adults in development sample (DS) and 78 in temporary validation sample (TVS). Urinary iothalamate clearance (reference method), and different predictive variables were used to develop candidate equations to estimate GFR. The performance was assessed through 10-fold cross-validation in DS, and by direct validation in TVS, using root mean squared error (RMSE), correlation (r), bias, P15, P30 and correct classification percentage (CC%) in CKD stages. The Argentinian equation (AE) chosen is based on a quasi-likelihood model which predicts GFR from creatinine, age, sex, single kidney, albumin and urea. Within the previous creatinine based equations (MDRD, MCQ, CKD-EPI and EKFC), the ones with the best performance were CKD-EPI 2009 and 2021. In the DS, AE showed lower RMSE, similar r, higher P15, median bias closer to zero and higher CC% compared to CKD-EPI 2009, and very slight differences in comparison to CKD-EPI 2021. In the TVS, AE presented lower RMSE, higher (or equal) r, P30 and CC%, and median bias closer to 0 compared to CKD-EPI in its two versions. In addition, it presented higher P15 than CKD-EPI 2009. In conclusion, AE presented a better performance to estimate GFR in Argentinian people and its use could have a positive impact on the clinical management of these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knowledge of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) plays a fundamental role in renal evaluation and in the detection and monitoring of chronic kidney disease (CKD)1. Measurement of GFR by urinary clearance with iothalamate is considered one of the gold standards2,3. This method is impractical to use daily with all patients and its availability is scarce in our region. Serum creatinine is commonly used to estimate GFR using different formulas4. These were developed in populations with characteristics different from those of our patients (physical build, eating habits, ethnic groups). The number of Latin American subjects included in these studies is low and therefore they are underrepresented5,6,7,8,9. For this reason, the predictions of these formulas may not be directly extrapolated to our population. To our knowledge, at present there is no equation developed in Latin America.

The objective of this study was to develop a new equation to estimate GFR, based on data from Argentina, and to compare its performance with that of currently available equations.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out.

Samples, inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adults residing in Argentina whose GFR had been measured with iothalamate at the Hospital Privado Universitario de Córdoba between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2017 were included. Patients with any of these criteria were excluded: <18 years, non-Latin American, being hospitalized during GFR measurement, cirrhosis, decompensated heart failure and some missing data regarding: age, gender, weight, height, history of solitary kidney, serum creatinine, urea or albumin. When the same patient had two or more GFR measurements during the study period, only the first was included. This first sample was used to develop the new candidate equations and we call it the development sample (DS). In this sample, internal validation was also carried out, using the 10-fold cross-validation resampling method10. From here, the equation with the best performance among the candidate models was chosen, according to the different measures that are described later.

In a second instance a new sample was added. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were exactly the same, only the recruitment period was later (between January 1, 2018 and July 1, 2019). This second sample was used to evaluate the performance of the new equation and compare it with the previous equations. We call it a temporary validation sample (TVS).

Laboratory methods

They are specified in supplementary data.

Statistical analysis

To compare the baseline characteristics of the samples we used: for categorical variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and for continuous variables, the student’s t test for independent samples and unequal variances.

Development of the new equations and nomenclature

Predictive equations were constructed in the DS using linear regression models11, generalized linear models12 and quasi-likelihood models13. In all candidate models, three predictor variables were always used: creatinine, age, and sex. Additional variables were added, both in their natural scale, with transformations and the possible interactions between them. We selected 9 candidate models. To refer to each model we use a nomenclature with 2 codes. The first code refers to the type of model: L (linear), G (generalized linear) and Q (quasi-likelihood). The second code refers to the number of explanatory variables: 3 (creatinine, sex and age), 4 (previous + single kidney) and 6 (previous + urea and albumin). More details on the development methodology and selection of candidate models are described in Supplementary Material, along with the expression of the different equations considered.

Metrics for equation performance

The measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) is the GFR of each individual measured by iothalamate. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is the GFR predicted by equations. Precisely, when evaluating the performance of the nine candidate equations by 10-fold cross-validation, the eGFR is, for each observation in the DS, the estimated value from the equation that leaves that observation out. At each observation in the TVS, it is the estimated GFR using the chosen equation based on the DS. The performance of the new equations to predict the GFR was compared with the previous ones: Mayo Clinic Quadratic equation (MCQ)5, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease with 4 (MDRD-4) and 6 variables (MDRD-6)6, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 (CKD-EPI 2009)7 and 2021 (CKD-EPI 2021)8 and European Kidney Function Consortium (EKFC)9. It is worth noting that the most recommended CKD-EPI 2021 creatinine-cystatin C equation8 could not be considered in our study due to the unavailability of cystatin C measurements. Throughout this manuscript, when we mention CKD-EPI 2021 equation, we are referring to the one that uses only serum creatinine.

The metrics used to evaluate the performance of the equations were: (a) bias, defined as the difference between eGFR and mGFR by iothalamate. The closer to 0 the bias, the better the estimate. Values greater than 0 overestimate the true GFR and less than 0 underestimate it. It is summarized using the median, first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3); (b) Root mean squared error (RMSE); (c) Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between mGFR and eGFR; (d) P15 and P30, defined as the percentage of the eGFR values that are within ± 15% or ± 30% of the mGFR ones, respectively and (e) the correct classification percentage (CC%) defined as the percentage of patients well classified within the 5 stages of CKD according to the eGFR, taking the mGFR as a reference.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the R program14.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Privado Universitario de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina (HP-4-288). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All methods used were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

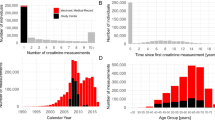

For the DS we considered 755 patients, of which 172 (22.8%) were excluded for different reasons (Figure S1) and 583 were finally included. For the TVS, we considered 118 new adult subjects, 40 (33.9%) were excluded for different reasons (Figure S1), and 78 subjects were included.

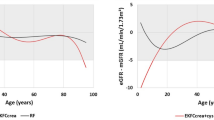

In the DS, 43.9% of the patients were male, with an average age of 46.3 ± 14.4 years, with a wide range of ages, weights, heights, and BMI among the included subjects (Table 1). In relation to comorbidities, 30% had obesity, 35.2% hypertension, 9.9% diabetes, and 6.7% had a single kidney. The request for the GFR measurement was for various reasons: 66.4% were evaluated as candidates to be kidney donors, 31.1% were suspected cases of chronic kidney disease, and 2.6% for another reason. There was a considerable variation among the participants’ laboratory analyses. The average mGFR was 91.1 ± 36.2 ml/min/1.73 m2 (min-max = 1.9–186.6 ml/min/1.73 m2) and 57.6% had an mGFR ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73 m2. No statistically significant differences were found between subjects included in the DS and TVS (Table 1). Figures S2 and S3 show the distribution of the main continuous variables in both samples.

Performance evaluation in the DS using 10-fold cross-validation

Within the previously existing equations, in the DS, CKD-EPI 2009 and CKD-EPI 2021 have a higher performance than MCQ, MDRD-4 and MDRD-6 taking into account all the performance criteria used (Table 2). CKD-EPI 2021 slightly improves the performance of the original CKD-EPI 2009, but there is a notable superiority of these two equations with respect to the rest. EKFC can be considered as having an intermediate performance between CKD-EPI in its two versions and the other equations, slightly surpassing MDRD-6 equation.

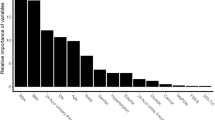

Within the candidate equations developed, those that use only 3 or 4 predictive variables have a worse performance than those that use 6. Hence, they are not shown in the tables. Q6 outperforms L6 and G6 in all performance metrics, presenting lower RMSE, higher r, P15, P30 (same as L6), CC% and median bias closer to zero.

In comparison to CKD-EPI 2009, Q6 presented lower RMSE, higher P15, median bias closer to zero, and higher CC%. In addition, from Q1, median and Q3 of the bias, a greater shift to the left is observed for CKD-EPI 2009. Compared with CKD-EPI 2021, Q6 obtained a median bias closer to 0 and a little lower interquartile range, and in the rest of the metrics had slightly lower or similar performance. Figure 1-A shows how the MDRD-4, MDRD-6, CKD-EPI 2009 and EKFC tend to underestimate GFR (bias less than 0) and MCQ tends to overestimate it (bias greater than 0). CKD-EPI 2021 and Q6 present a median bias (horizontal line inside the box) closer to 0.

Boxplots of the bias of the different equations in the development sample using 10-fold cross-validation (A) and in the temporary validation sample (B). MDRD-4 and MDRD-6 = Modification of Diet in Renal Disease with 4 and 6 variables; MCQ = Mayo Clinic Quadratic; CKD-EPI = Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 2009 and 2021; EKFC = European Kidney Function Consortium; L6 = linear model using 6 predictive variables; G6 = generalized linear model using 6 predictive variables; Q6 = quasi-likelihood model using 6 predictive variables; AE = Argentinian Equation.

This good performance of Q6 can be observed in both men and women (Table S1).

In patients with mGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 all equations considerably diminish their performance, although MDRD-4 and MDRD-6 appear to present some advantage (Tables S2 and S3). However, these equations perform worse for mGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and overall. Q6 and CKD-EPI are the equations that show the most consistent performance across all stages.

There is a high percentage of coincidences to discriminate a GFR < or ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, between Q6 and CKD-EPI 2009 (96%) and between Q6 and CKD-EPI 2021 (96.7%), (Table S4). Of the 23 subjects in whom there is a discrepancy with CKD-EPI 2009, 14 were correctly classified by Q6 and 9 by CKD-EPI 2009, using the mGFR as the reference pattern. Of the 19 subjects in whom there is a discrepancy with CKD-EPI 2021, 11 are correct for Q6 and 8 for CKD-EPI 2021. The number of subjects misclassified was 41 with Q6, 44 with CKD-EPI 2021 and 46 with CKD-EPI 2009.

From this internal validation analysis, Q6 was chosen as the best predictive model, from now on called Argentinian Equation (AE).

Performance evaluation in the TVS

Like in the DS, the ones with the best overall performance within the previously existing equations are CKD-EPI 2009 and CKD-EPI 2021, since they present lower RMSE, median bias closer to zero and higher P15 and percentage of correct classification (Table 2). There is a clear difference with the rest of the equations. MDRD-6 is the equation that presents the highest P30. AE presents a superior performance to the previous equations taking into account all the metrics, except P15, which is only surpassed by CKD-EPI 2021. Figure 1-B shows how MDRD-4, MDRD-6, CKD-EPI 2009 and EKFC tend to underestimate GFR, MCQ tends to overestimate it and CKD-EPI 2021 and AE present a median bias closer to 0.

This good performance of AE can also be observed in both men and women in this validation (Table S5).

In patients in the TVS with mGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 most of the equations generally show a diminution in performance, although the results are less reliable due to being based on only 14 observations (Table S6). From Table S7, AE appears to be the equation that remains the most stable across the different stages.

There is also a very high percentage of coincidences to discriminate a GFR < or ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, between AE and CKD-EPI 2009 (96.2%) and between AE and CKD-EPI 2021 (98.7%), (Table S8). Here there are only 3 discrepancies between AE and CKD-EPI 2009 (2 hits for AE and 1 for CKD-EPI 2009), and only 1 discrepancy between AE and CKD-EPI 2021 (hit for CKD-EPI 2021, corresponding to a subject for whom AE estimates a GFR of 61.3 ml/min/1.73 m2, very close to the discrimination cut-off point of 60). The number of subjects misclassified was 2 with AE, 1 with CKD-EPI 2021 and 3 with CKD-EPI 2009.

The regression coefficients derived from the DS were updated using also the TVS, giving the following final equation:

Figure 2 shows the scatter plot of the final AE predictions using the mGFR in the full sample as a reference, and Figure S4 shows the plot of standardized residuals versus predicted values (where a cloud of points without a specific pattern is observed).

Discussion

In the development of none of the current equations to estimate GFR, a significant number of Latin Americans were included5,6,7,8,9. In this study, we develop the first equation to estimate the GFR in our region.

Regarding the characteristics of the patients in our study, there is a wide range of age, BMI and GFR among the included subjects. This is beneficial since the equation can be used in the future only in patients with characteristics similar to those included in the original study. However, there are subpopulations that are poorly represented, such as very elderly patients or with extreme values in BMI. This could translate into lower future performance in these subpopulations. Furthermore, this equation should not be used in subjects excluded from the sample (pregnant women, children, ethnicity other than Latin American, among others).

The methodology applied in our study for the construction of the new equation was similar to that used in the previous ones, but with some particularities: (A) to estimate the GFR in previous equations, multiple linear regression models were used to initially predict the log-transformed response variable, and in a second instance exponentiate the prediction to finally inform it on its original scale5,6,7,8,9. In our study we used, in addition to this, generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link function, and quasi-likelihood models. This allowed the response variable to be predicted directly on its natural scale, without the need to transform the data, but rather by transforming the population mean12, and also, in the case of quasi-likelihood models13, without the need to assume a specific distribution beforehand. None of the previous equations used this kind of models. We believe that the direct prediction of the response variable at its natural scale without the need for data transformations is the most appropriate estimation tool, and the superior performance in the validation comparison supports this affirmation. (B) In nearly all previous equations, creatinine was transformed using a natural logarithmic scale6,7,8,9. In our study, creatinine was transformed using a square root, and when compared to the log transformation, this approach demonstrated clearly superior performance (results not shown). (C) The single kidney explanatory variable was not included in any of the previous equations5,6,7,8,9. Compared to individuals with two functioning kidneys, monorenal patients not only have a reduced renal mass but also undergo adaptive hemodynamic and structural changes, as well as alterations in tubular creatinine secretion15,16,17, which could modify creatinine concentration and therefore, the prediction of GFR from it. These are the reasons why we believe it is important to consider a specific coefficient to estimate the GFR in this type of patients. The incorporation of this variable added an important predictive capacity and performance to the models. (D) As in the MDRD-66, albumin and urea were added. In individuals with reduced muscle mass, malnutrition, and renal failure, serum creatinine levels typically do not rise significantly. This is because the production of creatinine, which is primarily derived from muscle metabolism, is altered18. In such cases, urea levels may increase, as urea production is not directly dependent on muscle mass, while albumin levels may decrease, serving as a marker of protein malnutrition. For this reason, we believe that these two variables add an important adjustment to the prediction of the GFR from a theoretical point of view. However, the inclusion of subjects with reduced muscle mass or malnutrition in our study is scarce, so a study with a larger number of subjects with these characteristics will be necessary to evaluate their performance in the future. (E) In both MDRD-4, MDRD-66, CKD-EPI7,8 and EKFC9, an independent sample from the development sample was used for internal validation, and in MCQ5 the same sample was used but through the bootstrapping methodology. In our study, two methods were carried out, the first using the DS, but through 10-fold cross-validation (methodology used only in the Bis equation to preselect candidate equations, but we do not use this equation as a comparator, since it only applies to subjects over 70 years19). This resampling method is the one recommended today and is considered the best internal validation method, since it allows to use all data for the development of equations and also for validation20. The technique of randomly dividing the entire sample and using one part for development and the other part for validation is a strategy widely used but is not recommended20. (F) In a second instance, a temporary validation was carried out. Some authors recognize temporary validation as a type of external validation, since, although it is carried out by the same researchers, it is carried out with a sample of independent subjects, from a late period20. According to the International Guide Tripod20 it could be said that temporary validation is a type of external validation, although it can also be considered as intermediate between the internal and external ones. In our study, the performance of the new equation was even higher in this TVS than in the DS. This acquires great relevance, since they are completely independent patients to those used for the construction of the equation. In addition, this double validation allows to reaffirm the superior performance of our equation in local patients.

P30 is one of the best tools to compare the performance of the different equations, since it combines accuracy with precision21,22. In the study where the CKD-EPI 2009 equation was constructed, the P30 obtained in the MDRD internal validation (the comparator at that time) was 80.6 and that of CKD-EPI was 84.17. The P30 attained in the validation of the CKD-EPI 2021 equation was 86.5 for white race8. In our study, the main comparators obtained very high values for P30 in the internal validation sample (CKD-EPI 2009: 88.5 and CKD-EPI 2021: 85.9) and even the CKD-EPI 2009 P30 value is better than that obtained in the internal validation of their own study. Having a comparator with such good performance placed a higher demand for the new equations; even so, the P30 obtained by AE in the TVS was higher (89.7). The KDOQI guidelines suggest that equations to predict GFR should ideally have a P30 ≥ 90% in validation populations23. However, of currently available equations that only use serum creatinine as an endogenous marker, none have achieved that goal18,24. Murata et al.25 evaluated 2324 white patients and gained a P30 value for CKD-EPI of 75%. Selistre et al.26 evaluated the performance of CKD-EPI in 9430 Caucasian adults and the obtained P30 was 80%. The P30 value of 89.7% obtained in the TVS of our study, is assimilated to the ideal value of 90% suggested by the guidelines. In addition, currently a P30 > 80% is considered acceptable for most circumstances of utility in clinical practice8.

Within the previous equations, both MCQ, MDRD-4 and MDRD-6 presented in our study a clearly inferior performance than CKD-EPI in any of its versions, as shown by other authors21,27,28. Although MDRD-4 and MDRD-6 seem to have slight performance advantages in patients with mGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (as these equations were developed exclusively for this type of patients), these findings are not relevant due to the global performance decrease observed in all equations in the DS and the small number of subjects with this characteristic included in the TVS (only 14 subjects). A relevant finding is the generally good performance obtained from CKD-EPI in Latin American subjects. These equations had not been previously validated in our population. The results obtained are similar to or better than those originally published. Even so, and despite having used a DS with significantly fewer observations, the performance achieved by the new AE surpassed both, with a more evident superiority with respect to CKD-EPI 2009 than to CKD-EPI 2021. As stated before, CKD-EPI 2021 expression considered in our study is the one based only on serum creatinine (without cystatin C). In its original study8, that equation, which excludes race, did not yield better results than previous CKD-EPI among white subjects, did not reduce difference in bias between black and non-black participants and also resulted in a lower CC% in both groups. Therefore, CKD-EPI 2009 should be the main comparator to consider in our study. Inker et al8 suggest using the 2021 version of CKD-EPI that combines creatinine with cystatin C (and does not include race), as it improves the performance of the equation that uses creatinine alone and leads to smaller differences between race groups. In our setting, the availability of cystatin C is limited, and its cost remains high, making it unlikely that the clinical implementation of this new equation will become widespread in the short to medium term29. For U.S. adults, the Task Force established by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) has specifically recommended the implementation of equations developed without the inclusion of the race variable, because not only exclude race from the calculation and reporting of eGFR, but also incorporate diversity in their development30,31. However, they also recognize that Latin American populations remain underrepresented in eGFR research30,31. Furthermore, there is a growing emphasis on promoting more data collection and research from Latin America and other diverse populations and we believe that this work contributes to that effort32,33.

According to the results of the second National Health and Nutrition Survey carried out in 2019, the prevalence of CKD in adults in Argentina is 12.7% (approximately 4 million adults)34. The new equation developed (AE) achieved better performance than the previous one, with a high percentage of correct classification in the different CKD stages. This approach could not only provide benefits for patients by improving the diagnosis of the severity of renal involvement but also influence clinical management. It could impact treatment decisions, including the initiation, adjustment, or discontinuation of medications; vaccination strategies; dietary recommendations; timing of vascular access creation; initiation of renal replacement therapy; or renal transplantation. Furthermore, it may affect the actual prognosis, which varies depending on the stage of CKD. In other words, the correct classification allows appropriate management and treatment and this could generate benefits in the morbidity and mortality of patients in the short and long term.

The weaknesses of this study are: The sample does not encompass all type of subjects within the population. As in the previous equations, there are subgroups of patients that are not well represented. Besides, a classic external validation was not performed, although temporary validation could be considered a type of external one, or something in between of an internal and an external validation. The strengths of the study are: The inclusion of subjects with a wide range of characteristics allows the equation to be used in a large number of patients. For the development of the equations, novel statistical tools and strategies were added. Serum creatinine determinations are standardized by the IDMS reference method, which gives external validity to the study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first equation to estimate the GFR in the Latin American region, a population poorly represented in the previously available equations. The incorporation of this new equation could improve GFR predictions in our population and indirectly the management of these patients.

In conclusion, CKD-EPI 2009 and 2021 showed good performance among Argentine patients, surpassing the other existing equations, so they could be used when predictive variables are not available to calculate eGFR by AE. The first equation to estimate the GFR in Argentina was developed (AE), outperforming the estimation of GFR in subjects residing in Argentina compared to the currently valid equations. Its use could have a positive impact on the clinical management of these patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 3(1), 1–150 (2013).

Smith, H. W. The kidney: structure and function in health and disease (Oxford University Press, 1951).

Elwood, C. M., Sigman, E. M. & Treger, C. The measurement of glomerular filtration rate with 125I-sodium iothalamate (Conray). Br. J. Radiol. 40(476), 581–583 (1967).

Inker, L. A. & Titan, S. Measurement and estimation of GFR for use in clinical practice: core curriculum 2021. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 78(5), 736–749 (2021).

Rule, A. D. et al. Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 141(12), 929–937 (2004).

Levey, A. S. et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 145(4), 247–254 (2006).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150(9), 604–612 (2009).

Inker, L. A. et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C–based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl. J. Med. 385(19), 1737–1749 (2021).

Pottel, H. et al. Development and validation of a modified full age spectrum creatinine-based equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate: a cross-sectional analysis of pooled data. Ann. Intern. Med. 174(2), 183–191 (2021).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Resampling methods. In: (eds James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R.) An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R 175–201 (Springer, 2013).

Rosner, B. Fundamentals of biostatistics (Cengage Learning, 2015).

Myers, R. H., Montgomery, D. C., Vining, G. G. & Robinson, T. J. Generalized linear models: with applications in engineering and the sciences 522 (Wiley, 2012).

Wedderburn, R. W. M. Quasi-likelihood functions, generalized linear models, and the Gauss-Newton method. Biometrika 61(3), 439–447 (1974).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2020). Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

Kaufman, J. M. et al. Compensatory adaptation of structure and function following progressive renal ablation. Kidney Int. 6(1), 10–17 (1974).

Herrera, J. & Rodríguez-Iturbe, B. Stimulation of tubular secretion of creatinine in health and in conditions associated with reduced nephron mass. Evidence for a tubular functional reserve. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off. Publ. Eur. Dial Transpl. Assoc. Eur. Ren. Assoc. 13(3), 623–629 (1998).

Rodríguez-Iturbe, B., Herrera, J., Marín, C. & Mañalich, R. Tubular stress test detects subclinical reduction in renal functioning mass. Kidney Int. 59(3), 1094–1102 (2001).

Levey, A. S., Coresh, J., Tighiouart, H., Greene, T. & Inker, L. A. Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16(1), 51–64 (2020).

Schaeffner, E. S. et al. Two novel equations to estimate kidney function in persons aged 70 years or older. Ann. Intern. Med. 157(7), 471–481 (2012).

Moons, K. G. M. et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 162(1), W1–73 (2015).

Earley, A., Miskulin, D., Lamb, E. J., Levey, A. S. & Uhlig, K. Estimating equations for glomerular filtration rate in the era of creatinine standardization: a systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 156(11), 785–795 (2012).

Shen, C. et al. Performance of the CKD-EPI equation to estimate GFR in a longitudinal study of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off J. Natl. Kidney Found. 69(3), 482–484 (2017).

Andrassy, K. M. Comments on KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 84(3), 622–623 (2013).

Porrini, E. et al. Estimated GFR: time for a critical appraisal. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15(3), 177–190 (2019).

Murata, K. et al. Relative performance of the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate among patients with varied clinical presentations. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6(8), 1963–1972 (2011).

Selistre, L. et al. Comparison of the Schwartz and CKD-EPI equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate in children, adolescents, and adults: a retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 13(3), e1001979 (2016).

Stevens, L. A. et al. Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off J. Natl. Kidney Found. 56(3), 486–495 (2010).

Kilbride, H. S. et al. Accuracy of the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) study and CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) equations for estimation of GFR in the elderly. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off J. Natl. Kidney Found. 61(1), 57–66 (2013).

Inserra, F. & Greloni, G. Nuevas ecuaciones basadas en creatinina y cistatina C para la TFGe, sin incluir raza. Rev. Nefrol. Diálisis Traspl. 42(2), 99–102 (2022).

Delgado, C. et al. Reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney diseases: an interim report from the NKF-ASN task force. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 78(1), 103–115 (2021).

Delgado, C. et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 79(2), 268–88e1 (2022).

Stevens, L. A. et al. Evaluation of the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation for estimating the glomerular filtration rate in multiple ethnicities. Kidney Int. 79(5), 555–562 (2011).

Madero, M. & Sarnak, M. J. Creatinine-based formulae for estimating glomerular filtration rate: is it time to change to chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation? Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 20(6), 622–630 (2011).

Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENNyS 2) 2019. Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social. Argentina. Available from: https://iah.msal.gov.ar/doc/705.pdf (2019).

Acknowledgements

To Fundación Nefrológica de Córdoba (Córdoba, Argentina) and Instituto Universitario de Ciencias Biomédicas de Córdoba (IUCBC, Córdoba, Argentina) for covering publication costs.

Funding

Takeda Argentina S.A, SeCyT-UNC (Project 33620180100055CB) and Gador S.A. financially supported registration to the Latin American Congress of Nephrology and Hypertension 2021, Latin American Congress of Statistical Societies 2021 and Kidney Week Annual Meeting 2023 respectively, where preliminary reports of this study were presented. This funding source had no involvement in the design, analysis, presentation, or interpretation of the results of the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.F. was responsible for manuscript writing, conception, design, statistical data analysis, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. M.L.N. was responsible for design, methodology, statistical data analysis, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. C.C. was responsible for conception, design, provided supervision and mentorship, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. W.D. was responsible for provided supervision and mentorship, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. J.D.A., P.L., E.J.S., S.N. and J.D.L.F. were responsible for critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández, P., Nores, M.L., Douthat, W. et al. Development and validation of a new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate in Argentinian adults. Sci Rep 15, 6183 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90092-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90092-2