Abstract

As the global population ages rapidly, ensuring the accessibility of senior centers is crucial for supporting the well-being and quality of life of older adults. This study aims to address the facility location problem for senior centers in upcoming super-aging societies. An optimization model is developed using a genetic algorithm to determine the optimal locations of senior centers. The objective is to minimize travel distances for older adults while accounting for constraints such as mobility limitations and the existing distribution of senior centers. The elbow method is employed to identify the optimal number of new centers, balancing service accessibility and resource allocation. Open data sources, i.e., floating population and geographic information in Seoul, are used to estimate demand at various locations. The results show that adding up to 15 new centers in Seoul effectively reduced average travel distances for older adults by 24%, from 0.85 km to 0.64 km. The introduction of these new centers is prioritized based on their impact on the community, i.e., reducing travel distances and redistributing demand from overburdened facilities. These findings provide a data-driven framework for urban planners and policymakers to strategically enhance senior service networks in rapidly aging societies. By improving access to senior centers, this approach can help promote active aging, reduce social isolation, and ensure a better quality of life for older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As societies around the world face rapid demographic shifts, the challenge of providing adequate services for aging populations becomes increasingly urgent. According to the World Health Organization, the global population aged 65 and above is projected to reach 1.5 billion by 2050, nearly doubling from 703 million in 20191. One of the key concerns in super-aging societies, where more than 20% of the population is aged 65 or older, is the availability and accessibility of senior centers2. Specifically, older adults who regularly attend such centers experience a 30% decrease in feelings of loneliness and a 25% improvement in overall life satisfaction3. Moreover, 75% of senior center participants visit their center 1 to 3 times per week, emphasizing the importance of convenient locations4. As such, these centers provide critical social, health, and recreational services that help maintain the quality of life for older adults5,6.

This issue is crucial for urban planners and policymakers, especially in countries like South Korea, Japan, and Europe, where aging populations are growing at unprecedented rates. For example, South Korea recorded a fertility rate of 0.72 in 2023, positioning it as the fastest-aging country in the world7. This current fertility rate is related to the characteristics of an aging society. It is expected to become a super-aged society by 2025, with older adults constituting 20.6% of its population. By 2035 and 2050, this will rise to 30.1% and 43.0%, respectively. Similarly, Japan, with a fertility rate of 1.2 in 2023, has one of the lowest birth rates globally and is the world’s oldest country, with 29.1% of its 125 million people aged 65 or older8. Japan has long grappled with the challenges of its aging society. In the European Union, the proportion of older adults is projected to increase from 31.4% in 2019 to 52.0% by 2050, underscoring the growing need for efficient senior services. Italy and Finland follow Japan in the global ranking, with 24.5% and 23.6% of their populations aged 65 or older, respectively.

In this context, numerous studies have been conducted on the needs of the aging population9,10. These studies have shown that senior centers play a crucial role in promoting active aging, reducing social isolation, and providing essential services such as health screenings, education programs, and recreational activities. For example, All About Older Adults found that 90% of participants reported that senior centers improved their quality of life11. Additionally, the ideal walking distance for older adults to access community facilities is around 400–800 m, or about a 5–10 min walk12. Furthermore, older adults have specific preferences and needs for walking routes and purposes when accessing senior centers6. Accessibility refers to the ease of reaching a specific location or service, encompassing various modes of transportation such as walking, public transit, and private vehicles13,14,15. Older adults tend to prefer paths with gentle slopes, safe crossings such as crosswalks and traffic lights, and shaded routes or those with resting areas like benches16,17,18. The availability of resting spaces every 300–400 m, such as benches or pergolas, significantly impacts the choice of walking routes for older adults9. Additionally, many older adults prefer combining multiple errands, such as visiting the senior center along with medical appointments or grocery shopping, rather than making a trip for a single purpose4. These factors emphasize the need not only for optimal facility placement but also for creating senior-friendly environments that accommodate both mobility preferences and the need for breaks during walks.

The facility location problem (FLP) is fundamental to addressing these challenges in facility site selection19,20. The p-median problem is one of the most popular methods in FLP. It involves placing a specified number (p) of facilities to minimize the total travel distance between demand points and their assigned facilities20. Based on this concept, the p-median problem has been extensively studied in various contexts, including healthcare, retail, and public services. Several methodologies have been proposed for solving the FLP, ranging from linear programming and heuristic approaches to more advanced techniques like genetic algorithms and machine learning models21,22. These methods are widely applied to optimize different objectives. For instance, the p-median problem focuses on minimizing the total distance between facilities and users, while the maximal covering location problem aims to maximize the number of customers covered within a specified service range21,22,23,24. In addition to these optimization techniques, there is a growing body of research that highlights the importance of incorporating social and environmental factors into the FLP25,26,27,28,29,30,31. For instance, several studies have shown that geographic and spatial disparities in access to healthcare facilities lead to significant health inequalities25,26. More recent studies have expanded on these models by incorporating advanced computational techniques. For example, a robust optimization framework for healthcare facility location was introduced, considering uncertainties related to demand, mobility, and health conditions of older adults28,29. However, the application of FLP in the context of senior centers within super-aging societies remains relatively underexplored.

Although previous studies on aging societies provide valuable insights, there is a lack of research on the facility location problem for senior centers, which is essential for the upcoming super-aging society. Existing studies often select locations from predefined alternatives rather than systematically exploring all possibilities. Moreover, many rely on simplified distance metrics like Euclidean distance, overlooking real-world constraints such as road networks and service coverage. This has the potential to result in suboptimal facility placements that fail to capture the optimal spatial distribution of senior centers in the real world. Therefore, this study aims to determine the optimal locations for additional senior centers, considering accessibility. Specifically, an optimization model is developed by integrating a genetic algorithm (GA), the FLP, and the elbow method to ensure a practical and effective facility location strategy. The objective function is set to minimize the travel distance between the senior center and demand points. Additionally, the elbow method is employed to determine the optimal number of centers considering accessibility and resource allocation. The proposed model is applied using open data sources from Seoul, i.e., floating population, building information, and existing senior center locations. The results contribute to an efficient and convenient center location strategy that enhances service accessibility for older adults in the upcoming super-aging society.

Methodology

Problem definition

This study aims to determine the optimal locations for senior centers by minimizing the total distance between the centers and demand points. The FLP is a type of optimization problem focused on identifying the best locations for facilities, such as warehouses, hospitals, or senior centers, to achieve specific goals19,21,22. These goals are typically centered around minimizing costs or optimizing service delivery.

As mentioned earlier, minimizing total distances is crucial because it directly affects the accessibility of essential services for older adults. Total distances are calculated by multiplying the distance between senior centers and demand points by the demand (i.e., the number of older adults). Since mobility decreases with age, shorter distances to senior centers can significantly enhance the quality of life by encouraging greater participation in social, health, and recreational services. Additionally, determining the appropriate number of centers is critical for balancing accessibility and resource allocation. Too few centers can result in overcrowding and long travel distances, while too many may strain financial and operational resources. Therefore, careful consideration of both location and quantity is essential to develop an efficient and effective network of senior centers that meets the needs of an aging population.

The FLP for senior centers focuses on determining both the optimal locations and the appropriate number of centers, with accessibility as a key factor. GA is widely used to solve optimization problems with high computational complexity, such as the FLP, which often involves a large number of census districts32,33. GA is effective because it explores multiple solutions simultaneously and excels at finding globally optimal solutions, making them particularly useful for problems with complex constraints. In this study, GA is employed to generate different combinations of candidate locations to identify the best sites for senior centers. The fitness function is designed to minimize total distances, and GA is used to select the optimal solutions. Subsequently, the elbow method is applied to determine the optimal number of centers by identifying the point at which improvements in fitness begin to plateau. Finally, the impact of the optimal solution is evaluated through a practical, real-world application. Table 1 presents the nomenclature used in the proposed FLP.

Facility location problem

Conventional FLP involves determining the optimal placement of limited resources to minimize operational costs or maximize service efficiency20–2123. FLP addresses the challenge of placing facilities in locations that best meet customer demand, considering factors such as distance, operating costs, and service responsiveness. Common applications of FLP include optimizing the locations of warehouses, hospitals, emergency service centers, and public facilities24,25,26,27.

In this study, an FLP model is used to optimize senior center locations with the following considerations. The proposed FLP approach involves selecting the optimal locations for senior centers to serve senior citizens within designated service areas. Specifically, the objective is to determine these optimal locations using latitude and longitude coordinates. The constraints include the origin, the destination, and a network that connects the origins to the destinations. The FLP consists of a facility set denoted by \(\:F\), a set of demand points denoted by \(\:D\), and a directed graph represented by \(\:G\). In this study, all facilities are considered homogeneous, meaning that all senior centers offer the same service capacity and functionality. The problem is formulated using the mathematical concepts of nodes and edges in a graph. In this representation, a node corresponds to either a facility or a demand point, while an edge represents the connection between two nodes in the network. The mathematical notation used to define nodes and edges is described below.

Let \(\:G=(D\cup\:{F}_{e}\cup\:{F}_{c},E)\) be an undirected graph, where \(\:D=\{{d}_{1},{d}_{2},\dots\:,{d}_{m}\}\) represents demand points,\(\:\:{F}_{e}=\{{f}_{1},{f}_{2},\dots\:,{f}_{r}\}\) represents existing senior centers, and \(\:{F}_{e}=\{{f}_{r+1},{f}_{r+2},\dots\:,{f}_{r+q}\}\) represents potential locations for new senior centers. The set of edges \(\:E\) denotes the connections between these nodes, and the distance between two nodes, \(\:{d}_{i}\) and \(\:{f}_{j}\), is represented as\(\:\:dist({d}_{i},{f}_{j})\), measured using the network distance (e.g., along roads or pathways). Each demand point \(\:{d}_{i}\) has an associated demand \(\:{p}_{i}\), and the decision variable \(\:{x}_{ij}\) indicates whether a senior center at location \(\:{f}_{j}\) serves the demand at \(\:{d}_{i}\). If \(\:{f}_{j}\) serves \(\:{d}_{i}\), then \(\:{x}_{ij}=1\); otherwise, \(\:{x}_{ij}=0\). Every demand point \(\:{d}_{i}\) must be served by exactly one senior center, which is ensured by the constraint \(\:\sum\:_{j\in\:F}{x}_{ij}=1\forall\:i\in\:D\). Additionally, new senior centers can only be built at candidate locations, and their number is limited to \(\:k\), a pre-determined value. The total number of new facilities built is represented by \(\:\sum\:_{j\in\:{F}_{c}}{y}_{j}=k\), where \(\:{y}_{j}\) is a binary decision variable indicating whether a new senior center is built at \(\:{f}_{j}\). A demand point \(\:{d}_{i}\) can only be served by \(\:{f}_{j}\) if \(\:{f}_{j}\) is either an existing facility \(\:{(f}_{j}\in\:{F}_{e})\) or has been newly constructed \(\:({f}_{j}\in\:{F}_{c})\).

The objective is to minimize the total travel distance weighted by demand. This is expressed as the sum of the products of the demand at each point, the distance to the assigned senior center, and the decision variable \(\:{x}_{ij}\). The objective function and constraints ensure that all demand is served, the number of new facilities is within the limit, and senior centers are used efficiently to minimize travel distances. The objective function and constraints are expressed as follows.

Subject to.

The objective function (1) aims to minimize the total travel distance between demand points and their assigned senior centers, weighted by the demand at each point. Constraint (2) ensures that each demand point is assigned to exactly one senior center, meaning that every demand point is exclusively served by a single center. Constraint (3) enforces that demand points can only be assigned to senior centers that are either existing \(\:{(f}_{j}\in\:{F}_{e})\) or newly constructed \(\:{(f}_{j}\in\:{F}_{c})\). Constraint (4) ensures that the total number of newly constructed senior centers is equal to the predetermined value \(\:k\). Constraint (5) defines \(\:{x}_{ij}\) as binary values, indicating whether a specific demand point \(\:{d}_{i}\) is assigned to a particular senior center \(\:{f}_{j}\). Constraint (6) defines \(\:{y}_{j}\) as binary values, indicating whether a new senior center is built at a candidate location \(\:{f}_{j}\).

Genetic algorithm

The GA is used to solve the facility location optimization problem by generating different combinations of candidate locations and updating them to find better solutions32. Specifically, GA, inspired by natural selection, is well-suited for complex problems such as NP-hard problem33. For example, in this study, the candidate locations include all coordinate points within Seoul, covering a continuous range of latitude and longitude values. For example, in this study, the candidate locations include all coordinate points within Seoul, covering a continuous range of latitude and longitude values. In such cases, the computational complexity increases significantly due to the vast number of possible facility placements. GA efficiently navigates this large solution space by iteratively refining solutions, allowing for practical and scalable optimization in real-world applications.

It starts with an initial population, where each individual represents a potential solution. These solutions are evaluated based on a fitness function, which considers distance and demand. Through selection, crossover, and mutation, better solutions are gradually generated. Crossover combines parts of different solutions, while mutation introduces random changes to avoid local optima. This iterative process continues until a stopping criterion is met, such as reaching a predefined number of generations or achieving solution convergence. GA effectively balances minimizing distances with constraints, making it a powerful approach for solving the FLP.

Elbow method

The elbow method is used to determine the optimal number of new senior centers. The FLP is run for varying numbers of new senior centers, from 1 to 100. The elbow method is then applied as a post-processing technique. It evaluates the trade-off between the number of centers and the total distance of assigning demand points to them. The method finds the point where adding more facilities greatly reduces the total distance, but after that, the improvement slows down. This “elbow” point shows the best number of new senior centers, balancing shorter travel distances with the right number of facilities. This approach helps avoid having too many or too few facilities, ensuring resources are used efficiently. It offers a clear, data-driven way to choose the best number of new senior centers, improving overall efficiency.

Application

Data description

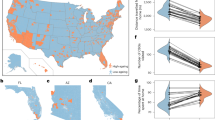

The government of Seoul has operated an open big-data portal (https://data.seoul.go.kr/) designed to make a wealth of public data readily accessible to citizens, researchers, and organizations. This platform serves as a hub of information from various public institutions, fostering collaboration and facilitating data-driven decision-making. The portal offers a diverse range of datasets spanning multiple domains, including weather, geography, transportation, and socioeconomic indicators, providing valuable insights into various aspects of life in Seoul. This study used public data from Seoul, including floating population data, building information, and senior center locations. Figure 1 shows the public data sources used in this study.

First, the demand is estimated using floating population data, which provides dynamic population distributions at the administrative census district level and reflects population patterns throughout the day. The strength of floating population data lies in its highly detailed spatial resolution. For example, residential population data divides Seoul into 426 administrative districts (dong), whereas floating population data segments the city into approximately 19,153 census blocks. Additionally, administrative district population statistics have the potential to include individuals who do not actually reside in a given area, which may affect accuracy. In contrast, floating population data is collected using mobile location information to capture real-time population movements and adjust the total population accordingly, resulting in more accurate population statistics. This high spatial resolution and precise data contribute to more realistic analyses and more informed decision-making. Therefore, using floating population data from a specific time period as a proxy for the resident population allows for a more accurate estimation34. The demand is defined as the number of older adult residents in each area. To estimate this, the population aged 65 and over is identified using floating population data recorded at 3:00 a.m., a time when most older adults are likely to be at home.

Second, building information was incorporated to refine the demand estimates. In the FLP, the placement of facilities is determined based on the distances between demand points and facilities, making it essential to allocate demand to individual buildings accurately. Precise demand allocation ensures that the analysis reflects realistic spatial relationships, leading to more effective facility placement21,22,23,24. The building data used in this study includes attributes such as the total floor area for each structure in Seoul. The total floor area was used as a weighting factor to assign the population to each building. Specifically, the floating population of each district was distributed across buildings based on their total floor area, under the assumption that larger buildings are likely to accommodate more people. This proportional assignment ensures more accurate population estimates for each building, reflecting real-world population patterns across the city. Finally, senior center location data was utilized. This was used to identify current service coverage and identify gaps where new senior centers might be required. This integrated dataset, which combines population demand, building information, and existing senior center locations, is used as the foundation for the FLP in this study. The public data sources from August 29th, 2024, are used in this study. This dataset was selected because it was the most recent available and represented the day with the highest floating population of individuals aged 65 and over. This setup was utilized to ensure efficient handling of the dataset and accurate execution of the analysis. The number of senior floating population, buildings, and existing senior centers are 1,461,082, 16,315, and 170, respectively.

Parameter tuning for genetic algorithm

Since the FLP is an NP-hard problem, a GA is used to find the optimal solution. Several parameters are required to run the GA, and optimizing these parameters is crucial for maximizing the algorithm’s performance. The optimal parameter values help GA find the global optimum solution efficiently and reduce computation time. The key parameters of GA include population size, generation, mutation rate, and convergence. The population size represents a set of candidate solutions; a larger population size increases the chance of finding diverse solutions but can also lead to longer computation times. Generation refers to the number of iterations, with solutions improving progressively over time. Mutation rate indicates the probability of mutations occurring, where genes are randomly altered during offspring generation to explore new solutions. Convergence refers to the condition that stops the algorithm when the same results are repeated.

The grid search method is used to determine the optimal parameters for the optimization model. In this method, predefined ranges of values are assigned to each parameter, and all possible combinations of these values are systematically tested to evaluate their performance. The parameters under consideration included population size, number of generations, mutation rate, and convergence criteria. To ensure a comprehensive exploration of the solution space, an additional scenario involving 100 potential new senior centers is simulated. Each combination of parameters is tested by running the model, and the performance is evaluated based on its ability to minimize travel distance while maintaining resource efficiency. After completing the grid search, the optimal parameter values are identified as follows: a population size of 200, 5000 generations, a mutation rate of 0.03, and a convergence threshold of 100. These settings are selected for their superior performance in balancing computational efficiency with solution quality, ensuring robust optimization results.

Result of optimal senior center locations

With the proposed FLP, optimal locations for senior centers were identified by minimizing the total travel distance for older adults. Specifically, the optimal locations for senior centers were determined using latitude and longitude coordinates. The candidate locations include all coordinate points within Seoul, with latitude ranging from 37.42824 to 37.69892 and longitude ranging from 126.76442 to 127.18451. The coordinate system used is WGS 84 (EPSG:4326). The data processing and analysis were conducted using Python (version 3.9) and QGIS (version 3.34). The computations were performed on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor, 32GB RAM, and Windows 10 operating system. A total of 10 scenarios were optimized. The base scenario included 170 existing centers, and additional scenarios were created by adding up to 50 more centers in increments of 5. Three key metrics were used to evaluate the performance of these scenarios: total distance (per 100 km), average distance per person (km), and improvement per additional center (m). Here, the distance used was the network distance (e.g., along roads or pathways). Specifically, the total distance metric was used to measure the overall travel burden for all users, indicating how effectively the network of senior centers reduced the total travel distance. The average distance per person metric was used to assess individual accessibility, showing how far each older adult had to travel on average to reach the nearest center. The improvement per additional center metric measured the marginal benefit of each new center in reducing travel distance, providing insight into the efficiency of adding more centers.

The results of the optimal senior center location problem are shown in Table 2. The findings indicated that both the total travel distance and the average travel distance per person steadily decreased as the number of additional centers increased. For example, the base scenario with 170 existing centers showed a total distance of 1,229.7 (1000 km). However, this total distance decreased to 934.4 (1000 km) when 50 centers were added, representing a reduction of about 23.9%. Similarly, the average travel distance per person decreased from 0.84 km to 0.64 km, a reduction of about 24.0%. These results implied that increasing the number of senior centers had a significant positive effect on reducing travel distances, thereby enhancing overall accessibility for the older adult population.

However, the impact of each additional center in reducing total distances showed diminishing returns. As more centers were added, the improvement in travel distance per additional center decreased. For example, adding 5 centers showed an improvement of 9.8 m per center. In contrast, adding 50 centers showed an improvement of only 4.0 m per center. This suggested that the marginal benefit decreased with each additional center while adding more centers initially had a substantial impact. This finding implied that increasing the number of centers became less efficient due to the diminishing returns in travel distance reduction.

The elbow method was used to identify the most efficient number of additional centers. The x-axis represented the number of additional centers, ranging from 0 to 50, while the y-axis showed the improvement in travel distance per additional center (in meters). The blue curve indicated diminishing returns, as each additional center had a progressively smaller impact on reducing travel distances. A red line illustrated a hypothetical linear trend, serving as a reference to highlight the deviation from a constant rate of improvement.

The elbow point, where the curve bent sharply, was around 15 additional centers. This suggested that adding up to 15 centers led to significant reductions in travel distance, but beyond this point, the marginal benefit of each new center dropped noticeably. Specifically, after 15 centers, the improvement per center decreased more rapidly, indicating that further investments in additional centers would not have yielded proportional benefits in reducing travel distances. Therefore, 15 additional centers were considered optimal, as this was the point where the trade-off between cost and benefit was most favorable. Adding more than 15 centers would have resulted in diminishing returns, making it less cost-effective to continue expanding the number of centers. The result of the elbow method is shown in Fig. 2.

Impact of optimal senior center locations on community

With the optimal solution, the impact of senior centers on the community was identified. The impact was evaluated using three key metrics: the number of centers, distance per person, and demand per center. The results of the optimal placement of senior centers are shown in Table 3. The optimal scenario resulted in an increase in the number of centers by 15, from 170 to 185. Of these, 95 centers remained unchanged in their operation, and 90 centers were affected by the addition of new facilities. This redistribution of centers helped improve accessibility, especially in areas that previously had limited access to senior services.

The distance per person decreased from 0.85 km to 0.74 km, indicating that the additional centers effectively reduced the overall travel distance for older adults. The average distance for the unaffected centers remained constant at 0.74 km. In contrast, the average distance for the impacted centers significantly dropped from 1.54 km to 0.77 km. This demonstrates that the newly added centers greatly improved accessibility, particularly in areas with previously limited access.

The demand per center also decreased from 8,595 to 7,898, as the new centers distributed the demand load more evenly. Unaffected centers showed no change in demand, which remained steady at 6,854. In contrast, the demand for impacted centers decreased significantly from 10,799 to 8,999. This redistribution reduced the burden on previously overused centers and balanced the number of users across the network.

In summary, the addition of 15 new centers had a positive effect on the community by decreasing travel distances for older adults and balancing the demand across the network. This made it easier for older adults to access centers, reduced congestion at existing facilities, and improved overall service quality. These optimized results are expected to enhance older adult welfare and improve service accessibility throughout the community.

Figure 3 shows the impact of adding 15 new senior centers. Figure 3(a) illustrates the average distance per person to the nearest senior center. Areas shaded in darker red indicate regions where residents currently travel longer distances, up to 4 km, to access a center. The new centers, marked in blue, are strategically placed in these high-demand areas to improve service accessibility for underserved populations. Figure 3(b) shows the improvement in travel distance with the new centers. Darker blue areas represent regions where the travel distance has decreased significantly, by up to 3 km. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the new centers in reducing travel burdens for residents, particularly in areas that were previously underserved.

Figure 3(c) shows the demand per center, with circle sizes representing the number of users each center serves. Larger circles indicate higher demand. Before the addition of new centers, some existing centers (gray circles) experienced high demand, creating potential service bottlenecks. The new centers (blue circles) help redistribute this demand more evenly across the network. Figure 3(d) shows the change in demand per center after the new centers were added. Impacted centers (pink circles) experienced a decrease in demand because new centers (blue circles) are absorbing the redistributed demand. This map highlights how the addition of new centers has helped balance the user load across the network, reducing congestion in previously overburdened centers.

Overall, these maps show that the addition of 15 new centers has effectively improved service accessibility and balanced demand, leading to a more equitable distribution of resources throughout the community.

Prioritization of the 15 new senior centers

The optimal solution from the FLP was estimated to involve adding 15 new senior centers. However, implementing all the new centers at once may not be feasible; a phased approach is a more practical and effective policy strategy. To prioritize this phased implementation, the impact of each potential location on the community was evaluated using three key metrics: total improved distance (km), shifted demand from existing facilities, and improved distance per capita (km).

The results of the 15 new senior centers with the optimal location are shown in Table 4. Based on the total improved distance, Gaebong-dong in Guro-gu had the highest priority, with a total improved distance of 21,392 km. Additionally, this location was estimated to have the largest shifted demand, with 19,790 users expected to be redistributed from existing centers. The improved distance per capita was also substantial, at 1.08 km, reflecting a considerable decrease in travel burden for individual users. Dangsan-dong and Hwagok-dong followed as the next highest priorities, based on the total improved distance. Dangsan-dong was projected to achieve a total improved distance of 13,364 km and redistribute 12,839 users, with an improved distance per capita of 1.04 km.

Other notable locations included Sinyeong-dong and Ichon-dong, which, despite having lower total improved distances and total demand, showed high values for improved distance per capita, at 1.17 km and 1.12 km, respectively. This suggested that even though the overall number of affected users was smaller, new centers in these areas would still have had a substantial positive impact on individual users.

These results offer valuable guidance for prioritizing new senior centers in Seoul based on policy goals. For city-wide improvements, the total improved distance metric is recommended, as it identifies locations that will significantly reduce overall travel distances for the older adult population, enhancing accessibility across the city. However, if the goal is to achieve targeted improvements in specific areas, the improved distance per capita metric is more suitable, as it highlights locations where new centers would provide substantial individual benefits. Ultimately, the choice of prioritization depends on whether the focus is on maximizing the overall impact or on addressing localized needs. Regardless of the approach, adding new centers in the identified high-priority locations would alleviate pressure on existing facilities and greatly improve access to services for older adults.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of existing and new senior centers in five major districts of Seoul: Gangseo, Gangnam, Seongbuk, Gangbuk, and Gwanak. The existing and new senior centers were colored grey and blue respectively. The numbers on the blue circles, ranging from 1 to 15, refer to the rank of each center based on its anticipated impact on the respective area.

The results showed that the top three ranked new centers were concentrated in the Gangseo district. This suggested that Gangseo was the district most urgently in need of additional infrastructure to support its older adult population. Similarly, several high-impact new centers were planned for the Gangnam district, with centers ranked 4th, 7th, and 12th. This indicated that Gangnam was the second most critical area after Gangseo for expanding senior services. In the Seongbuk and Gangbuk districts, several mid-impact new centers were planned, including those ranked 5th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 11th, 13th, and 14th. This suggested a moderate but notable need for additional facilities in these areas to alleviate the pressure on existing centers and improve service accessibility for the older adult population. Lastly, new centers ranked 9th and 15th were located in the Gwanak district. Although these centers were ranked lower in priority, they were still necessary to enhance service accessibility for the older adult population in this area.

Overall, the results of the impact rankings by district indicated that the placement of new centers was strategically planned to reflect the unique characteristics and demand in each area. This targeted approach is anticipated to improve access to senior services across Seoul and reduce disparities between districts.

Discussions

This study proposed an optimization model to address the facility location problem for senior centers in upcoming super-aging societies. The results demonstrated that adding up to 15 new centers could reduce the average travel distance for the older adult population by approximately 24%, from 0.85 km to 0.64 km. Specifically, prioritizing locations such as Gaebong-dong and Dangsan-dong, which showed the highest improvement in travel distance and demand redistribution, emphasizes the importance of focusing on high-need areas16. However, beyond the addition of 15 centers, the marginal benefits of reducing travel distances began to diminish, indicating that further expansion might not yield proportional benefits. This insight is crucial for policymakers, especially when considering the optimization of resource allocation in the context of limited budgets and rapidly aging populations17,35.

Moreover, the study’s findings align with previous research that stresses the need for strategic location planning to mitigate service disparities21,22,23,24,25. The results suggest that areas with previously high demand, such as the central and southern districts of Seoul, would benefit the most from additional centers. These areas, currently served by overburdened facilities, would experience reduced travel times for older adults, contributing to a more equitable distribution of resources and improved service accessibility19,26.

From an economic perspective, adding a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 50 senior centers is expected to reduce total travel distance from 1,229.7 (1000 km) to 1,089.1 (1000 km) and 934.4 (1000 km), respectively. This reduction in travel distance can be translated into economic benefits by applying a walking speed of 4 km/h and a time value of $4.28 per hour36. Based on this, assuming a 30% utilization rate of senior centers, the estimated annual economic benefit ranges from $1,647,991 to $3,462,021. This finding highlights that strategically placed new centers significantly enhance accessibility to senior services and generate substantial socio-economic benefits4,9,10.

Overall, these findings highlight the importance of targeted investments in senior center infrastructure to support the growing older adult population in super-aging societies. Ensuring both sustainability and efficiency in service expansion, policymakers can better address seniors’ needs by focusing on high-demand areas and optimizing resource allocation.

Conclusion

This study proposed an optimization model for solving the FLP for senior centers in super-aging societies. The results indicated that the addition of up to 15 new centers could reduce average travel distances for older adults by approximately 24%, from 0.85 km to 0.64 km. Moreover, the marginal benefits diminished beyond this point, suggesting that 15 new centers are the optimal number to achieve substantial improvements in accessibility without overextending resources. These findings highlight that strategic placement not only reduces travel distances but also helps redistribute demand, alleviating pressure on existing centers and improving overall service delivery.

This study made three key contributions to optimizing the facility location problem for senior centers in super-aging societies. First, it developed an optimization model specifically tailored to the senior center problem, considering factors such as senior demand and accessibility. Specifically, an optimization approach was devised by integrating heuristic algorithms, the FLP, and the elbow method to find a practical solution. Second, it evaluated the impact of the proposed facilities to establish a priority order for their introduction. Lastly, the model incorporated practical constraints such as mobility limitations, providing a realistic framework that can be refined and adapted to other cities facing similar demographic challenges.

Although the proposed model showed significant performance, several issues require further investigation. The use of static demand data may not capture fluctuations in center usage over time, and the exclusion of factors such as public transport availability and socio-economic differences could affect the accuracy of the model’s predictions. Future research should consider integrating real-time data and additional variables to enhance the robustness of the model.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and health 2018. URL: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health [accessed 2024-11-24].

Li, S. A., Duan, H. A., Smith, T. E. & Hu, H. Time-varying accessibility to senior centers by public transit in Philadelphia. Transp. Res. Part. A: Policy Pract. 151, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.06.020 (2021).

National Academies of Sciences, Division of Behavioral, Sciences, S. & Division, M. Board on behavioral, Sensory Sciences, … loneliness in older adults. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health care System. National Academies. (2020).

Pardasani, M. & Berkman, C. New York City senior centers: who participates and why? J. Appl. Gerontol. 40 (9), 985–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820917304 (2021).

Donovan, N. J. & Blazer, D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: review and commentary of a national academies report. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry. 28 (12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005 (2020).

Liao, H. W. & DeLiema, M. Reimagining senior centers for purposeful aging: perspectives of diverse older adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 40 (11), 1502–1510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464821996109 (2021).

CNN South Korea’s birth rate is so low, the president wants to create a ministry to tackle it. URL: https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/09/asia/south-korea-government-population-birth-rate-intl-hnk/index.html [accessed 2024-09-24].

BBC. Japan population: One in 10 people now aged 80 or older. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66850943 [accessed 2024-09-24].

Remillard, E. T., Campbell, M. L., Koon, L. M. & Rogers, W. A. Transportation challenges for persons aging with mobility disability: qualitative insights and policy implications. Disabil. Health J. 15 (1), 101209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101209 (2022).

Robnett, R., Brossoie, N. & Chop, W. Gerontology for the Health Care Professional, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. (2018). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315207735

All About Seniors. The Evolving Roles of Senior Centers in the 21st Century. https://www.allaboutseniors.org/the-evolving-roles-of-senior-centers-in-the-21st-century

Etman, A. et al. Characteristics of residential areas and transportational walking among frail and non-frail Dutch elderly: does the size of the area matter? Int. J. Health Geogr. 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-7 (2014).

Hwang, H., Cho, S. H., Kim, D. K. & Kho, S. Y. Development of a model for evaluating the coverage area of transit center using smart card data. J. Adv. Transp. 2020 (1), 8819791. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8819791 (2020).

Lee, E. H., Lee, I., Cho, S. H., Kho, S. Y. & Kim, D. K. A travel behavior-based skip-stop strategy considering train choice behaviors based on smartcard data. Sustainability 11 (10), 2791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102791 (2019).

Shin, H., Kim, D. K., Kho, S. Y. & Cho, S. H. Valuation of Metro crowding considering heterogeneity of route choice behaviors. Transp. Res. Rec. 2675 (2), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198120948862 (2021).

Dabelko-Schoeny, H. et al. Using community-based participatory research strategies in age-friendly communities to solve mobility challenges. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 63 (5), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1769787 (2020).

Lee, E. H. & Jeong, J. Assessing equity of vertical transport system installation in subway stations for mobility handicapped using data envelopment analysis. J. Public. Transp. 25, 100074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubtr.2023.100074 (2023).

Liu, C., Bardaka, E., Palakurthy, R. & Tung, L. W. Analysis of travel characteristics and access mode choice of elderly urban rail riders in Denver, Colorado. Travel Behav. Soc. 19, 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.11.004 (2020).

Celik Turkoglu, D. & Erol Genevois, M. A comparative survey of service facility location problems. Ann. Oper. Res. 292, 399–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-019-03385-x (2020).

Drezner, Z. Dynamic facility location: the progressive p-median problem. Location Sci. 3 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0966-8349(95)00003-Z (1995).

Das, S. K., Roy, S. K. & Weber, G. W. Heuristic approaches for solid transportation-p-facility location problem. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 28, 939–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-019-00610-7 (2020).

Filippi, C., Guastaroba, G., Huerta-Muñoz, D. L. & Speranza, M. G. A kernel search heuristic for a fair facility location problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 132, 105292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2021.105292 (2021).

Daskin, M. S. & Maass, K. L. The p-median problem. In Location Science (21–45). Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13111-5_2 (2015).

García, S. & Marín, A. Covering location problems. Location Sci. 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32177-2_5 (2019).

Jia, T. et al. Selecting the optimal healthcare centers with a modified P-median model: a visual analytic perspective. Int. J. Health Geogr. 13, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-42 (2014).

Shariff, S. R., Moin, N. H. & Omar, M. Location allocation modeling for healthcare facility planning in Malaysia. Comput. Ind. Eng. 62 (4), 1000–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2011.12.026 (2012).

Shehadeh, K. S. Reducing disparities in transportation distance in a stochastic facility location problem. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 153, 104199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2023.104199 (2023).

Silva, A., Aloise, D., Coelho, L. C. & Rocha, C. Heuristics for the dynamic facility location problem with modular capacities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 290 (2), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2020.08.018 (2021).

Nasrabadi, A. M., Najafi, M. & Zolfagharinia, H. Considering short-term and long-term uncertainties in location and capacity planning of public healthcare facilities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 281 (1), 152–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2019.08.014 (2020).

Seyedi, S. B., Attari, M. Y. N., Ghadim, V. A. P. & Ala, A. An efficient computational model for unequal-area dynamic facility layout problems considering input/output locations under algorithms case. Sādhanā 49 (3), 211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12046-024-02550-8 (2024).

Attari, M. Y. N., Ala, A., Ahmadi, M. & Jami, E. N. A highly effective optimization approach for managing reverse warehouse system capacity across diverse scenarios. Process. Integr. Optim. Sustain. 8 (2), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41660-023-00388-x (2024).

Lee, E. H. & Kim, G. J. Multi-objective optimization of submerged floating tunnel route considering structural safety and total travel time. Structural Engineering and Mechanics, An Int’l Journal, 88(4), 323–334. (2023). https://doi.org/10.12989/sem.2023.88.4.323

Han, S. W., Lee, E. H. & Kim, D. K. Multi-objective optimization for skip-stop strategy based on smartcard data considering total travel time and equity. Transp. Res. Rec. 2675 (10), 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211013044 (2021).

Lee, C., Lee, E. H. & Cities Evaluation of urban nightlife attractiveness for Millennials and Generation Z. 149, 104934. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.104934

Wong, R. C. P., Szeto, W. Y., Yang, L., Li, Y. C. & Wong, S. C. Public transport policy measures for improving elderly mobility. Transp. Policy. 63, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.12.015 (2018).

Study on Investment Evaluation Strategies for Pedestrian and Bicycle Transportation Infrastructure. Republic of Korea Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). (in Korean) (2019).

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the Sahmyook University Research Fund in 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.H.L. conceived and conducted the experiments, analyzed the results, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. J.J. corresponded with participants. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read it, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, E.H., Jeong, J. Facility location problem for senior centers in an upcoming super-aging society. Sci Rep 15, 6317 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90096-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90096-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Data-driven (hybrid) decision-making framework to define dairy factory location

OPSEARCH (2025)

-

Evaluation of NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 to simulate precipitation using multi-criteria decision-making analysis over Türkiye

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2025)