Abstract

Contrast-enhanced chest CT (CECT) is more sensitive than non-contrast-enhanced chest CT (NCECT), but NCECT may have comparable efficacy in detecting new primary lung cancer among stage I NSCLC survivors after two years of surveillance. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of NCECT versus CECT for surveillance among stage I NSCLC patients surviving two years after curative resection without disease recurrence. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with stage I NSCLC who underwent curative-intent lung resection between January 2009 and December 2017 using the Registry for Thoracic Cancer Surgery at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Overall survival, recurrence-free survival, and cost effectiveness were compared between patients undergoing surveillance with CECT and NCECT. Among 3248 patients, 1002 (38.8%) patients underwent NCECT surveillance. During a median follow-up of 2.3 years (interquartile range, 1.5–3.9 years), a total of 208 deaths were observed. Although patients undergoing NCECT surveillance had 0.04 more deaths per 100 person-year compared with patients undergoing CECT surveillance (95% CI −0.36 to 0.44), this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.27 vs. 1.31 per 100 person-years; HR, 1.10; 95% CI 0.81–1.50). Regarding cost effectiveness, CECT group had a gain of 0.024 quality-adjusted life-year but $785 higher total cumulative cost per patient compared to NCECT. There was no difference in recurrence and mortality between NCECT and CECT for surveillance among stage I NSCLC patients who survived two years after surgery without disease recurrence. Further randomized clinical trials are required to confirm the findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since pivotal randomized controlled trials of low-dose chest computed tomography (LDCT)-based lung cancer screening have reported significant reductions in lung cancer mortality1,2, the number of patients diagnosed with asymptomatic early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is expected to increase. In patients with a good performance status, the current standard of treatment is surgery providing a chance of cure, thereby increasing the number of lung cancer survivors. Accordingly, surveillance after curative resection is becoming an increasingly important component of survivorship care, particularly patients with stage I NSCLC3,4,5.

However, there is currently a lack of consensus regarding imaging modalities for NSCLC surveillance after curative-intent therapy. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend chest computed tomography (CT) with or without contrast, while the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines recommend chest CT with contrast (preferred) or without contrast when conducting surveillance for recurrence during the first two years post-treatment6,7. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) currently recommends chest radiography or CT every six months during the first two years post-treatment8.

Contrast-enhanced chest CT (CECT) is more sensitive than non-contrast-enhanced chest CT (NCECT) for detecting the hilar and mediastinal recurrence9,10. As the risk of locoregional recurrence, including hilar, mediastinal, and pleural recurrence, is greatly increased in the first two years after surgery, CECT is the preferred imaging modality during the first two years of post-treatment surveillance, according to some authors11,12. However, NCECT may have comparable efficacy in detecting new primary lung cancer among stage I NSCLC survivors after two years of surveillance as the risk of locoregional recurrence is low and the detection of lung parenchymal lesions is clinically important. In other words, NCECT may have comparable efficacy to CECT for surveillance in the first two years post-treatment due to the substantial risk of lung-to-lung metastasis or the development of a new primary lung cancer13,14. In addition, the use of intravenous contrast poses a significant risk to patients with contrast allergy or kidney dysfunction, with repeated CECT examinations further increasing the risk of adverse reactions15,16,17,18. Accordingly, CECT should be used with caution in surveillance settings. However, there is currently a lack of evidence regarding the efficacy of NCECT for surveillance of stage I NSCLC patients surviving two years after surgery without signs of recurrence. Thus, we hypothesized that NCECT would be as effective as CECT for postoperative surveillance in patients with stage I NSCLC who have been disease-free for over two years following curative resection. This study aimed to evaluate the overall survival, recurrence-free survival, cost effectiveness, and quality of life between patients undergoing surveillance with CECT and NCECT to evaluate the efficacy of NCECT for postoperative surveillance among stage I NSCLC patients surviving two years after curative resection without disease recurrence.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Among 3,248 patients who underwent curative resection for stage I NSCLC without recurrence within two years of surgery, 1,002 (38.8%) patients underwent NCECT surveillance. At the index years which was 2 years since surgery, patients undergoing NCECT for surveillance were more likely to be older (61.08 vs. 59.94 years; p < 0.01), have undergone sublobar resection (26.3% vs. 17.7%; p < 0.01) and were less likely to have undergone mediastinal lymph node (LN) dissection (89.7% vs. 93.9%; p < 0.01) compared to patients undergoing CECT for surveillance (Table 1). PS matching yielded 1002 patients in the NCECT group and 1002 patients in the CECT. The distribution of co-variables after PS matching was well-balanced with standardized mean differences of less 0.1 (data not shown).

Outcomes

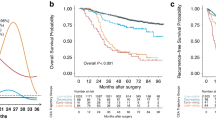

Over a median follow-up period of 2.3 years (interquartile range, 1.5–3.9 years) starting from the two-year postoperative mark, total of 208 deaths were observed. Although patients undergoing NCECT for surveillance had 0.04 more deaths per 100 person-year compared with patients undergoing CECT for surveillance (95% CI −0.36 to 0.44), this difference did not reach statistical significance (1.27 vs. 1.31 per 100 person-years; HR, 1.10; 95% CI 0.81–1.50; Table 2 and Fig. 1). The risk of all-cause death in patients undergoing NCECT after two years of surveillance remained non-significant in multivariable analysis (adjusted HR 1.10; 95% CI 0.80, 1.51). IPTW adjustment analysis and PS matched analysis demonstrated a similar of risk of all-cause death in the NCECT and CECT groups (Table 2). In subgroup analysis, there was no difference in the risk of all-cause death in the NCECT group compared to the CECT groups. This was consistently observed across various subgroups, with no significant differences observed between any of the subgroups, including when patients were classified as having stage 1A or 1B disease (Fig. 2).

Among the 208 all-cause deaths, 20 cases were death due to lung cancer. Although NCECT were less likely to death due to lung cancer compared to CECT, there was no statistical significance due to small number of cases (Supplementary Table S1).

After the first two years of postoperative surveillance for stage I NSCLC, during which patients were monitored with either NCECT or CECT, a total of 93 recurrent cancer cases were identified in subsequent surveillance. Of these, 16 cases occurred in patients undergoing NCECT for surveillance and 77 cases occurred in patients undergoing CECT for surveillance (0.46 vs. 0.84 per 100 person-years; difference, −0.38; 95% CI −0.67 to −0.08). IPTW adjustment analysis and PS matched analysis demonstrated a similar of risk of recurrence in the NCECT and CECT groups. Among cases of recurrent cancer, the most frequent site of recurrence was the lung (NCECT group, 56.3%; CECT group, 49.4%) followed by the ipsilateral pleura (NCECT group, 25.0%; CECT group, 20.8%) and ipsilateral mediastinum (NCECT group, 25%; CECT group, 14.3%; Supplementary Figure). Compared to the patients undergoing CECT for surveillance, patients undergoing NCECT for surveillance had a lower probability of local recurrence being detected (0.20 vs. 0.09 per 100 person-years; difference, −0.12; 95% CI −0.26 to 0.02) than distant metastasis; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (0.48 vs. 0.32 per 100 person-years; difference, −0.16; 95% CI −0.40 to 0.07; Table 3).

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Regarding cost effectiveness, there was a net gain of 0.024 QALYs in the CECT group compared with the NCECT group during follow-up. The total cumulative cost per patient in the CECT group was estimated to be $785.668, which was higher than in the NCECT group. Consequently, the ICER was calculated at $33,063.248, more than $30,000 over the WTP cut-off. Accordingly, CECT for surveillance was not considered a cost-effective alternative during follow-up (Fig. 3). When we simulated considering the relatively higher mortality and recurrence rate setting, the CECT group had $367 higher costs and a net loss of 0.14 QALYs compared to the NCECT group (Supplementary Table S2).

Incremental cost-effectiveness plane for contrast CT compared with non- contrast CT at two years after surgery. Replications of the incremental cost effectiveness of contrast CT compared with non- contrast CT at 2 years after surgery are shown. The incremental cost-effectiveness plane represents the impact of contrast CT compared to non-contrast CT at two years after surgery in terms of the difference in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) and accompanying healthcare-related costs during a follow-up period of 5 years. Each of the 25,000 points represent the result of one bootstrap replication. The difference in cumulative costs is displayed on the vertical axis and the difference in QALYs is displayed on the horizontal axis. The average incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is indicated by the red dot. The willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $30,000 per QALY added (dashed line) is indicated in the plane.

Discussion

Using a large prospective registry, we observed no differences in recurrence and mortality between NCECT and CECT for postoperative surveillance among stage I NSCLC patients who survived two years after surgery without disease recurrence. CECT surveillance was associated with a small net gain in QALY but a higher total cumulative cost per patient compared to NCECT.

In the present study, postoperative surveillance using NCECT since two years after surgery for stage I NSCLC had no effect on all-cause mortality and lung cancer-related mortality compared with CECT. This finding may be attributable to the low rate of disease recurrence observed at two years after surgery. The risk of recurrence in patients undergoing curative resection of NSCLC is greatest during the first two years after surgery. The probability of recurrence then decreases after two years from surgery12,19,20, with the cumulative recurrence rate among stage I NSCLC patients reported to be 4.3–11.2%21,22. In the present, the recurrence rate at two years after surgery was less than 5%. In addition, the most frequent site of recurrence was the lung in both the CECT and NCECT groups. This finding corroborates the results of previous studies. Zhu et al. reported the incidence of postoperative recurrence in 994 patients with early-stage NSCLC demonstrating that recurrence was predominantly distant (87.5%) and the most common site of metastasis was the lung (34.0%)21. Parenchymal lung lesions can be easily detected by chest CT regardless of contrast administration. These findings a rationale that NCECT is not inferior to CECT for surveillance of early-stage NSCLC patients after two years postoperatively among patients with stage I NSCLC.

A U.S. population-based study reported 11.68% of patients with stage IA NSCLC developed second primary lung cancer, with the incidence of a second primary lung cancer increasing over time (1.5–6% per year)23,24. Therefore, the main goal of surveillance shifts toward the detection of new primary lung cancers at more than two years after surgery. The utility of NCECT as a screening modality for primary lung cancer has been clearly demonstrated in CT screening trials. Two recent trials established LDCT screening, which is conducted without contrast administration, as an important tool for the detection of early-stage NSCLC in patients at high risk of developing lung cancer1,2. Given the above findings, NCECT may have similar utility to LDCT in lung cancer screening of general at-risk populations at more than two years after surgery.

Regarding cost effectiveness, CECT was not found to be a cost-effective alternative after two years of surveillance. The present study found that a net gain of only 0.024 QALYs with the use of CECT surveillance during follow-up compared to NCECT. In contrast, the ICER was calculated as $33,063.248, which $30,000 more than the WTP cut-off. These results may be attributable to the incidence of recurrence at more than two years after surgery is very low, thereby reducing the survival benefit of CECT over NCECT surveillance.

The cumulative radiation exposure associated with repeated CT scans is an important consideration in long-term postoperative surveillance for lung cancer patients. While CT imaging remains a critical tool for detecting recurrences and new primary malignancies, the potential risks related to radiation exposure should be carefully evaluated alongside its diagnostic benefits. The radiation dose from chest CT scans varies depending on imaging protocols, scanner technology, and contrast usage. In general, NCECT and CECT deliver comparable radiation doses when performed under standard protocols. However, CECT may result in slightly higher radiation exposure due to the need for multiphase imaging or delayed-phase acquisition in certain protocols. The average effective radiation dose for a standard chest CT scan ranges from 5 to 7 mSv per scan, whereas LDCT, commonly used in lung cancer screening, reduces the radiation dose to approximately 1 to 2 mSv per scan25. In long-term lung cancer surveillance, where patients may undergo multiple scans over several years, the cumulative radiation dose becomes a relevant factor, particularly for younger patients or those with prolonged life expectancy. Although this study did not perform a direct radiation dose analysis, minimizing unnecessary radiation exposure in extended surveillance settings remains an important consideration. Future research should further investigate the long-term effects of radiation exposure and explore potential strategies for dose optimization in this patient population.

Several limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results of the present study. First, as a retrospective observational study, we could not determine false-positive or false-negative rates. Since NCECT and CECT were performed serially, and the recurrence was assessed based on interval change in serial CT findings, this approach made it difficult to accurately calculate false-positive and false-negative rates. Second, we were unable to exclude the possibility of selection bias as patients expected to have better prognosis may have been more likely to undergo NCECT for surveillance. In our study, the NCECT group had a larger proportion of patients who had undergone sublobar resection and a smaller proportion of those who had mediastinal LN dissection compared to the CECT group. This suggests a potential bias, likely due to the selection of patients with less aggressive tumors such as ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesions, which are associated with a better prognosis and might not require extensive lymph node dissection. Consequently, the less aggressive nature of these tumors might lead to reduced use of contrast-enhanced CT for surveillance. This trend could reflect a clinical decision to minimize intervention for patients with very low-risk tumors. To address this potential source of bias, we included only patients without recurrence at two years after surgery. Furthermore, we performed subgroup analyses and identified no factors significantly associated with risk of recurrence. Third, patients with a poor progression may not have attended our institution for surveillance and attended their local hospital instead. However, the present study was conducted in Korea which has a single-payer national health system. Thus, we were able to obtain clinical data for all participants from the national insurance system. Fourth, as our institution has strategies for preventing side effects of contrast media, the cost of contrast-associated side effects may have been underestimated. We therefore used the reported costs associated with side effects in previous literature in our cost-effectiveness analysis. Lastly, the results of the present study may not be generalizable to patients in other countries with different healthcare systems as the present study was conducted in Korea where the national healthcare system is centralized in a metropolitan city, Seoul. Fifth, we did not perform a direct comparison of the detection rates for complications such as pneumonia or pleural effusion between NCECT and CECT. However, since all patients underwent surveillance with chest CT, any differences in detecting these complications due to contrast use would likely be minimal. Previous studies have shown that CT, regardless of contrast administration, is highly effective in detecting pleural effusion and pneumonia26. Future research could further investigate whether contrast use provides any significant advantage in identifying these postoperative complications.

Despite these limitations, we believe this to be the first study to evaluate the efficacy and cost effectiveness of NCECT compared to CECT for surveillance of patients surviving more than two years after surgery without signs of recurrence using data from a large registry. We observed a potential benefit of NCECT surveillance in survivors of stage I NSCLC for a long-term follow-up period. Further randomized clinical trials are required to validate the findings of the present study.

Methods

Participants and design

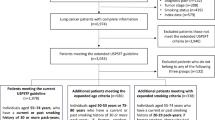

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Registry for Thoracic Cancer Surgery (RTCS) at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. The RTCS is a database that has prospectively collected information on all patients undergoing surgery at our institution since 1994 and includes data on clinical and pathologic parameters, perioperative treatment, surgery, and long-term survival. The RTCS is regularly updated by trained data managers using the electronic medical records of all patients. For the present study, we selected patients with stage I NSCLC who underwent curative-intent lung resection between January 2009 and December 2017 (n = 3913). To control for immortal time bias27, we included patients who were alive without any recurrence at two years after surgery (n = 3269). We then excluded 21 patients who were ineligible for CECT due to high serum creatinine levels. The final study analysis therefore comprised 3,248 patients. The study present was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Samsung Medical Center (IRB no. SMC 2020-07-028-002). The requirement for informed consent was waived as all data was de-identified.

This study was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Sociodemographic data from the time of diagnosis and clinical information from the time of diagnosis and post-treatment were from the RTCS. These data included information regarding disease staging (eighth edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM staging system for NSCLC), comorbidities, preoperative treatment, surgical and pathologic data, postoperative complications, and adjuvant treatment. We also obtained survival and recurrence data from the registry.

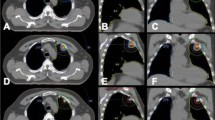

Surveillance imaging methods after two years of survivorship

Patients were regularly evaluated by chest CT with contrast every 3–4 months for the first two years following surgery. After two years of surveillance, chest CT was conducted every 6 months with or without contrast. NCECT was performed using thin-section images with a slice thickness of 1.25–1.5 mm. For CECT, imaging was conducted in two phases: a pre-contrast phase, which was performed similarly to NCECT with a slice thickness of 1.25–1.5 mm, and a post-contrast phase, which was acquired with a slice thickness of 3 mm after contrast administration. The choice of imaging modality (CECT or NCECT) after two years was determined by the physician's preference. Most providers tended to consistently use one method over the other. Patients were evaluated by positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scans, and biopsy when recurrence was suspected. Patients were classified into the CECT group and NCECT group according to the use of contrast media for surveillance CT at two years after surgery.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome of the present study was all-cause mortality, with patients followed from two years after surgery to the date of death from any cause or end of the study period (January 28, 2022). The secondary outcome was recurrence, with death prior to evidence of recurrence considered a competing event. Patients were included in the survival analysis model from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence, death, or last surveillance without evidence of recurrence, whichever came first. Data regarding site of recurrence (local, regional, and distant) was obtained by reviewing CT scans of patients with recurrence. In terms of distant, we excluded cases that had recurrence at sites outside the range of chest CT.

Cost and utility for quality-adjusted life-year

The costs of CECT and NCECT were obtained from our hospital enterprise data warehouse database. In this study, there were 3 health states for patients after lung cancer, including lung cancer-free survival, lung cancer recurrence, and death. Utility weights for the durations of non-recurrence and recurrence survival were obtained from existing literature28, while the utility weight for death was set to zero. Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were calculated by applying the respective utility weights to the actual duration of each health state. We calculated total quality-adjusted life-year (QALYs) for each group by summing the QALYs from the three statuses, combining mortality (years of life lost), recurrence (years lived with recurrence) and NSCLC (years lived with NSCLC) effects. These weighted durations were then summed to calculate the total quality-adjusted survival for each patient. Additional cumulative annual medical costs due to recurrence were obtained from a previous study29. Costs were limited to medical costs excluding non–medical and indirect costs. Furthermore, the probability and cost of side effects related to CECT were obtained from a previous study30.

Statistical analyses

The cumulative incidence of clinical events was presented as a Kaplan–Meier estimate. Hazard ratios (HRs) for death were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. Subdistribution hazard ratios (sHR) for recurrence were estimated using the Fine and Gray method to account for competing risks due to death31. For both outcomes, multivariable models were adjusted for age at the time of surgery, sex, histology, pathologic T category, extent of resection (lobectomy versus more extensive resection than lobectomy), year of surgery, and adjuvant treatment. The assumption of proportionality was assessed graphically using log-minus-log plots. Cox proportional hazard models for all clinical outcomes satisfied the proportional hazards assumption.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to minimize confounding effects. First, inverse probability treatment weighted (IPTW) Cox proportional hazard regression was used to compare differences in clinical outcomes between groups. All variables were included in this model. Each participant was assigned a weight based on the likelihood of undergoing NCECT at two years after surgery. Second, propensity-score (PS) matched cohort analysis was used to compare differences between group. The PS was estimated within each emulated cohort to minimize systematic differences in baseline characteristics between the CECT and NCECT at two years after surger. A logistic regression model was used to estimate the probability of receiving NCECT based on covariables, including age at the time of surgery, sex, histology, pathologic T category, extent of resection, year of surgery, and adjuvant treatment. To address potential biases, we applied 1:1 propensity score nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.2 on the propensity score scale. The matching was performed using the MatchIt package in R (version 4.0.3). Baseline differences between the two groups were evaluated before and after matching using absolute standardized differences, with values > 0.2 indicating significant imbalance.

Additionally, subgroup analyses were performed according to age at the time of surgery, sex, histology, pathologic T category, extent of resection (lobectomy versus more extensive resection than lobectomy), year of surgery, and adjuvant treatment. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

For the cost-effectives analysis, PS matched cohort analysis was used to compare differences between group. The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis are presented as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), an indicator of incremental cost on additional QALYs gained from CECT at two years after surgery. We applied a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of US $30,000, which is close to the one-time (1x) gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of Korea in 2022 according to data from World Bank national accounts. Cost effectiveness was defined as an ICER lower than 1 × WTP threshold32. We also performed a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) using the bootstrap technique with the percentile method with 25,000 replications. As the mortality and recurrence rates were relatively low, we performed cost-effectiveness analyses in different healthcare systems based on a Markov model. We used a three-state Markov model that simulated: (1) no recurrence; (2) recurrence; and (3) death in lung cancer patients. Patients were initially allocated to lung cancer without recurrence and could either remain in the same state or transit to recurrence or death in every cycle according to the transition probability. The transition probability was calculated according to the annual rates of death and recurrence33. Cost and utility data were discounted by an annual rate of 4.5% according to the Korean Guidelines of Methodological Standards for economic evaluation (Supplementary Table S3).

All analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (StataCorp. 2011, College Station, TX) and R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Hong Kwan Kim, upon reasonable request. Data will be shared for non-commercial purposes only, subject to approval by the corresponding author, and provided that the requester has a valid reason for access. This is to ensure compliance with ethical standards and patient confidentiality regulations.

Abbreviations

- ACCP:

-

American college of chest physicians

- ASCO:

-

American society of clinical oncology

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced chest CT

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability treatment weighted

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- LDCT:

-

Low-dose chest computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NCCN:

-

National comprehensive cancer network

- NCECT:

-

Non-contrast-enhanced chest CT

- NSCLC:

-

Non–small cell lung cancer

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PS:

-

Propensity-score

- PSA:

-

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-year

- RTCS:

-

Registry for thoracic cancer surgery

- WTP:

-

Willingness-to-pay

References

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 (2011).

de Koning, H. J. et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1911793 (2020).

Mollberg, N. M. & Ferguson, M. K. Postoperative surveillance for non-small cell lung cancer resected with curative intent: developing a patient-centered approach. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 95, 1112–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.075 (2013).

Subramanian, M. et al. Imaging surveillance for surgically resected stage i non-small cell lung cancer: is more always better?. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 157, 1205–12171202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.09.119 (2019).

Westeel, V. et al. Chest CT scan plus x-ray versus chest x-ray for the follow-up of completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer (IFCT-0302): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00451-X (2022).

Ettinger, D. S. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 15, 504–535. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2017.0050 (2017).

Schneider, B. J. et al. Lung cancer surveillance after definitive curative-intent therapy: ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.02748 (2020).

Rubins, J., Unger, M., Colice, G. L. & American College of Chest, P. Follow-up and surveillance of the lung cancer patient following curative intent therapy: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guideline (2nd edition). Chest 132, 355S-367S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.07-1390 (2007).

Polat, G., Polat, M. & Meletlioglu, E. Effect of contrast medium on early detection and analysis of mediastinal lymph nodes in computed tomography. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 1992(69), 392–397. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20220869 (2023).

Takahashi, M. et al. Detection of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes by 16-row MDCT: is contrast material needed?. Eur. J. Radiol. 66, 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.05.028 (2008).

Demicheli, R. et al. Recurrence dynamics for non-small-cell lung cancer: effect of surgery on the development of metastases. J. Thorac. Oncol. 7, 723–730. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824a9022 (2012).

Lou, F., Sima, C. S., Rusch, V. W., Jones, D. R. & Huang, J. Differences in patterns of recurrence in early-stage versus locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 98, 1755–1760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.070 (2014).

Hamaji, M. et al. Surgical treatment of metachronous second primary lung cancer after complete resection of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 145, 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.051 (2013).

Leroy, T. et al. Let us not underestimate the long-term risk of SPLC after surgical resection of NSCLC. Lung Cancer 137, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.09.001 (2019).

Cha, M. J. et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media: A multicenter study of 196 081 patients. Radiology 293, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019190485 (2019).

Andreucci, M., Solomon, R. & Tasanarong, A. Side effects of radiographic contrast media: Pathogenesis, risk factors, and prevention. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 741018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/741018 (2014).

Lee, Y. C., Hsieh, C. C., Chang, T. T. & Li, C. Y. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury among patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing imaging studies: A meta-analysis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 213, 728–735. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.19.21309 (2019).

Kobayashi, D. et al. Risk factors for adverse reactions from contrast agents for computed tomography. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-18 (2013).

Hung, J. J. et al. Post-recurrence survival in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer with local recurrence. Thorax 64, 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2007.094912 (2009).

Karacz, C. M., Yan, J., Zhu, H. & Gerber, D. E. Timing, sites, and correlates of lung cancer recurrence. Clin. Lung Cancer 21, 127-135.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.12.001 (2020).

Zhu, J. F. et al. Time-varying pattern of postoperative recurrence risk of early-stage (T1a–T2bN0M0) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Results of a single-center study of 994 Chinese patients. PLoS One 9, e106668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106668 (2014).

Christensen, N. L. et al. Assessing the pattern of recurrence in Danish stage I lung cancer patients in relation to the follow-up program: Are we failing to identify patients with cerebral recurrence?. Acta Oncol. 57, 1556–1560. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1490028 (2018).

Johnson, B. E. Second lung cancers in patients after treatment for an initial lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1335–1345. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/90.18.1335 (1998).

Lou, F. et al. Patterns of recurrence and second primary lung cancer in early-stage lung cancer survivors followed with routine computed tomography surveillance. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 145, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.030 (2013).

Larke, F. J. et al. Estimated radiation dose associated with low-dose chest CT of average-size participants in the National Lung Screening Trial. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 197(5), 1165–1169 (2011).

Purysko, C. P., Renapurkar, R. & Bolen, M. A. When does chest CT require contrast enhancement?. Cleveland Clin. J. Med. 83(6), 423 (2016).

Parast, L., Tian, L. & Cai, T. Landmark estimation of survival and treatment effect in a randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 109, 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2013.842488 (2014).

Yang, S. C. et al. Dynamic changes of health utility in lung cancer patients receiving different treatments: A 7-year follow-up. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14, 1892–1900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.07.007 (2019).

Park, H. Y. et al. Lifetime survival and medical costs of lung cancer: a semi-parametric estimation from South Korea. BMC Cancer 20, 846. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07353-8 (2020).

Arana, E. & Catalá-López, F. Cost-effectiveness of iodinated contrast media for CT scanning in Spain: A decision-based analysis. Imaging Med. 4, 193 (2012).

Fine, J. P. & Gray, R. J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 94, 496–509. https://doi.org/10.2307/2670170 (1999).

Anderson, J. L. et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on performance measures and task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 2304–2322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.016 (2014).

van den Berg, L. L., Klinkenberg, T. J., Groen, H. J. M. & Widder, J. Patterns of recurrence and survival after surgery or stereotactic radiotherapy for early stage NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 826–831. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0000000000000483 (2015).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yeong Jeong Jeon: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Investigation, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & Editing Danbee Gang: Methodology, Formal analysis Software, Writing—Original draft, Visualization Junghee Lee: Resource, Data Curation Seong Yong Park: Investigation, Resource Jong Ho Cho, Yong Soo Choi, Jhingook Kim, Young Mog Shim: Investigation, Resource, Data Curation Ho Yun Lee: Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing Juhee Cho: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration, Supervision Hong Kwan Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, Y.J., Kang, D., Lee, J. et al. Efficacy of contrast versus non-contrast CT surveillance among patients surviving two years without recurrence after surgery for stage I lung cancer. Sci Rep 15, 6142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90124-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90124-x