Abstract

Dyslipidemia is a primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of dyslipidemia and its associated risk factors in the southwest region of Iran. This population-based cross-sectional study was conducted with 9846 participants aged 35 to 70 in southwest Iran. Data was collected on socioeconomic factors, demographic characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory tests, anthropometric measurements, and lifestyle variables. The criteria for dyslipidemia were based on the ATP III classification. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to control for potential confounders. Results showed that the overall prevalence of dyslipidemia was 43.5%, with abnormal levels of HDL, LDL, TC, and TG at 17.9, 21.8, 36.2, and 44%, respectively. The multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that males (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.74−2.14), individuals with abnormal waist circumference (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.67−2.12), those with low physical activity (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.15−1.46), smokers (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.05−1.31), rich people (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.04−1.36), and patients with hypertension (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.05−1.27) had higher odds of dyslipidemia. Our findings suggest that dyslipidemia is a complex condition that is influenced by various biological and lifestyle factors. Different prevention and treatment strategies may be necessary for various population subgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is a condition characterized by an imbalance of lipids, including cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)1. It can arise from various factors, such as diet1, tobacco exposure2, genetics, age3, sex2, alcohol use, hypertension, body weight, and abdominal obesity1.

The prevalence of dyslipidemia varies across different regions of the world, with hypercholesterolemia ranging from 22.6 to 54% across Africa, Southeast Asia, Europe, and the Americas4,5,6. In Iranian adults, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was found to be 81.0% (80.2–81.9), affecting 84.4% of women and 75.7% of men7. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), Dyslipidemia, specifically elevated total cholesterol (TC), is responsible for 2.6 million deaths annually and 29.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally8.

Dyslipidemia is a significant global risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality1. It can lead to premature atherosclerosis, potentially resulting in angina or heart attacks9. Elevated lipid levels are risk factors for atherosclerosis and can lead to symptomatic coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease10. However, dyslipidemia can be managed through lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise, as well as medications such as statins1.

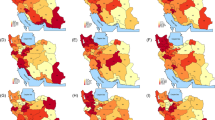

Despite the importance of dyslipidemia, which is considered one of the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, no recent study has been conducted on the prevalence of dyslipidemia and its risk factors in southwest Iran. The novelty of dyslipidemia prevalence research in Iran lies in its comprehensive approach to understanding the prevalence, risk factors, and geographical distribution of dyslipidemia in the country. The studies provide valuable insights into the prevalence of lipid abnormalities such as hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, high LDL-C, and low HDL-C, as well as the coexistence of these abnormalities in mixed dyslipidemia. Furthermore, the research highlights the regional variations in dyslipidemia prevalence across different provinces in Iran. These findings contribute to developing targeted preventive strategies and healthcare policies to address dyslipidemia and promote metabolic health in the country. A comprehensive epidemiological analysis of dyslipidemia would assist in providing essential baseline information about the disease burden, research priorities, optimal allocation of health system resources, and the development of effective screening programs. Therefore, we hypothesized that demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and comorbidity factors could be associated with dyslipidemia.

Results

Among 9846 participants, the mean ± SD of age was 48.76 ± 9.21 years (49.09 ± 9.24 in men and 48.53 ± 9.19 in women), and 59.1% of them were women. The overall prevalence of dyslipidemia was 43.5% (CI 95% 42.51–44.48), 52.7% (n = 2122) in men and 37.1% (n = 2160) in women). The mean ± SD of BMI was 28.82 ± 5.31 (27.50 ± 4.63 for men and 29.70 ± 5.54 for women).

Table 1 shows that dyslipidemia is significantly more prevalent among men, older participants, married individuals, residents of urban areas, educated people, richer individuals, participants with abnormal waist circumference, patients with hypertension, and people with low physical activity.

Besides, the results of the chi-square for trend test showed that with increasing age, level of education, physical activity, and wealth status, dyslipidemia also increases.

The prevalence of abnormal lipid profiles, including HDL, LDL, TC, and TG, were 17.9% (CI 95% 17.13–18.66), 21.8% (CI 95% 20.99–22.63), 36.2% (CI 95% 35.25–37.16), and 44% (CI 95% 43.01–44.98) respectively. The mean levels of triglyceride, total cholesterol, LDL-c, and HDL-c were 1.85 ± 1.23 mmol/L, 4.90 ± 1.04 mmol/L, 2.76 ± 0.85 mmol/L, and 1.30 ± 0.31 mmol/L respectively. Table 2 demonstrates that all lipid profile parameters show a statistically significant difference between both sexes (p < 0.05). Further details are provided in Supplementary table 1.

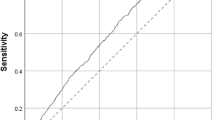

The logistic regression model performed the crude and adjusted odds ratios to assess the strength of associations and control for potential confounders. The odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals are reported in (Table 3). We included all variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the multivariable logistic regression model. Based on the Hosmer–Lemeshow test results, the model’s goodness of fit was acceptable (Chi-square = 7.57, df = 8, P = 0.48).

The crude odds ratios for all assessed variables, except age, were statistically significant (p < 0.05). However, age is usually an important potential confounder so, we included age and the other covariates in the multivariate logistic regression model. The adjusted odds ratios obtained from the multivariable logistic regression model are provided. There was a significant association between sex and dyslipidemia. The odds of having dyslipidemia in men were higher than in women (OR 2.25, 95% CI 2.01–2.52, p < 0.001). A direct and significant association between waist circumference and dyslipidemia was observed. The odds of having dyslipidemia were higher in participants with abnormal waist circumference than others, with an odds ratio of 1.88 (95% CI 1.67–2.12, p < 0.001). Additionally, a significant inverse association was found between physical activity level and dyslipidemia. The odds of having dyslipidemia decreased with higher levels of physical activity. Participants in quartile 4 of physical activity had 25% lower odds of dyslipidemia than those in quartile 1, with an odds ratio of 0.77 (95% CI 0.68–0.86, p < 0.001). We found an association between smoking and dyslipidemia. The odds of having dyslipidemia were higher in smokers compared to non-smokers, with an odds ratio of 1.13 (95% CI 1.01–1.26, p < 0.028). On the other hand, there were no significant associations between education levels (p > 0.05).

The population attributable fractions (PAF) were calculated for the assessed factors. In this study, abnormal waist circumference had the highest and smoke had the lowest PAF%. So, about 38.57, 7.93, 6.58, 2.58, and 3.96% of all cases in the population can be attributed to abnormal waist circumference, resistance in urban areas, poor physical activity, smoking, and hypertension, respectively.

The most significant risk factors that modify LDL goals were age (38%), hypertension (26.5%), and smoking (21.1%). Furthermore, age (58.2 vs. 38%), smoking (40.6 vs. 21.1%), and low HDL levels (27.5 vs. 17.9%) were more prevalent risk factors among men than women. In contrast, the prevalence of hypertension was higher among women compared to men (28.6 vs 23.4%) (Fig. 1).

Individuals without cardiovascular disease were classified into three groups based on Framingham Risk Score Levels. Most participants, 6524 (78%), were in the group with FRS < 10%. Our results showed that in the FRS > 20, FRS 10–20%, and FRS < 10% categories, 2.5, 3.1 and 2.6% needed TLC, and 3.2, 1.5 and 0.6% required TLC and DT, respectively (Fig. 2).

LDL cholesterol goals and cut points for therapeutic lifestyle changes and drug therapy in different risk categories. *Of the 9,846 study subjects evaluated in the analysis, 1486 subjects with cardiovascular disease were excluded from the calculation of the Framingham score. Consequently, the Framingham score was calculated for 8360 subjects.

Discussion

This study investigated the occurrence of dyslipidemia and its associated risk factors in southwest Iran. The findings suggest that dyslipidemia is a prevalent condition in this region of Iran, with 43.5% of the population affected. Also, abnormal HDL, LDL, TC, and TG were 17.9, 21.8, 36.2, and 44%, respectively. The study identified several factors associated with increased odds of dyslipidemia, including male gender, abnormal waist circumference, low physical activity, smoking, higher socioeconomic status, and hypertension.

In the final analysis, no significant association was found between age and dyslipidemia. Some studies suggest older individuals are more likely to develop dyslipidemia11, while others show older participants may have a lower risk compared to younger ones12. This discrepancy can be partly due to the different study populations, study designs, genetics, lifestyles, and hormonal characteristics.

The overall prevalence of dyslipidemia was 43.5%. The Tehran lipid and glucose study in Iranian adults reported the prevalence of dyslipidemia for both sexes at 83.2%13. These differences can be explained by different genetics and environmental factors between the people living in these two regions. Also, the lifestyle of the people is different between the areas. Tehran is a big city with the characteristics of an urban community, while Hoveyzeh is a small district, as an agricultural and animal husbandry community including several rural areas with more active lifestyles people. Besides, Hoveyzeh people use more traditional foods so, we expect lower rates of dyslipidemia in our study.

In this study, the odds of dyslipidemia were found to be higher in men compared to women. The higher prevalence of dyslipidemia in males may be due to a combination of lifestyle factors, hormonal factors, age, and genetics. Men are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and drinking alcohol, which can increase the risk of dyslipidemia2. Furthermore, testosterone levels have been linked to dyslipidemia, and men generally have higher levels of testosterone than women14.

We found a direct and significant association between waist circumference and dyslipidemia. Studies have shown that waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (W/Ht) are better indicators of dyslipidemia compared to body mass index (BMI) in Iranian adults15. The prevalence of central obesity, defined by different criteria, was notably high in Iranian adults. Central obesity was more prevalent among females and urban dwellers, highlighting the importance of considering waist circumference measurements in assessing cardiovascular risk factors and dyslipidemia in this population16.

We found a direct association between smoking and dyslipidemia. One study in the Kurdish population of Iran found that current smokers had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia compared to former smokers and non-smokers, with an increased risk of abnormal HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the Iranian population17. Cigarette consumption has been shown to disrupt lipid metabolism, leading to an increase in triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels6,18. Also, smokers are more likely to engage in unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as a high-fat diet, lack of exercise, and excessive alcohol consumption, which can further increase the risk of dyslipidemia19.

The study results indicated that the likelihood of dyslipidemia is significantly higher in individuals with lower physical activity compared to those who engage in high levels of physical activity. This finding has been shown in some studies. So that individuals with dyslipidemia tend to have lower levels of physical activity compared to those without dyslipidemia20,21. Several studies have shown that physical activity can help reduce the risk of dyslipidemia by promoting weight loss22, increasing HDL cholesterol levels23, lowering LDL cholesterol23, and improving insulin sensitivity24.

In this study, there was no significant association between education level and dyslipidemia. Some studies have found significant associations between education and blood lipid levels11,25, while others have not. Education level may have a weaker influence on dyslipidemia than other factors such as lifestyle and genetics. One study found that the association between education and dyslipidemia differed by sex and income level26.

The results of our study did not show a statistically significant relationship between residence types and dyslipidemia. A study in rural and urban China found that the prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar among rural and urban participants2. Another study of adult residents of Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia, found that dyslipidemia was unacceptably high among all residents, regardless of their wealth index27. The reasons for these differences are not entirely clear, but some factors that may contribute include differences in lifestyle, diet, and access to healthcare2.

In line with our study, studies in Ethiopia and China found no significant association between wealth index and dyslipidemia2,28. These findings indicate that while socioeconomic status and wealth index may influence specific health outcomes, the prevalence of dyslipidemia does not consistently show a significant difference based on these factors. Other factors, such as lifestyle, diet, and access to healthcare, may have a more prominent impact on the prevalence of dyslipidemia in different populations2,25.

The mechanisms responsible for the association between hypertension and dyslipidemia are complex and involve multiple pathways, including endothelial dysfunction, hormonal imbalances, and metabolic disturbances29. Our study showed a significant association between hypertension and dyslipidemia. The result of young adults in Poland found that hypertension and dyslipidemia were significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Various epidemiological studies have shown the coexistence of dyslipidemia and hypertension in a range of 15 to 31%30. However, some other studies did not find a direct association between the two conditions30,31.

This study had some limitations, including using the cross-sectional design, which can only establish associations and not causality. In our population attributable risk formula, we used odds ratios instead of relative risks32. Another limitation of our study was that, since the outcome of interest was not rare, using the odds ratio instead of the relative risk in the Miettinen formula may lead to a some overestimation of the population attributable fraction (PAF). In this study, the family history of hyperlipidemia and diet intake were not investigated, which should be part of future studies. Furthermore, lifestyle variables, including smoking and physical activity, were assessed through self-reporting, which may have introduced response bias. On the other hand, the present study had several strengths. The measurement of dyslipidemia was performed with standard equipment and kits based on the valid guidelines of ATPӀӀӀ. This can reduce measurement errors and improve the accuracy of the estimated rates. The accuracy of lipid level measurements can be affected by factors such as the timing of the test, fasting status, and the use of different laboratory methods. Therefore, we used a standard laboratory protocol and laboratory quality control to increase the accuracy of laboratory findings. Our study used a large sample of participants, which enhances the statistical power and precision of the estimates. This representative population improves the generalizability of the results to the broader population. This study was conducted using a contextual cohort study design. Additionally, we used multivariable logistic regression analysis to adjust for potential confounding factors, which can increase the validity of the prevalence estimates and identify the independent effects of different risk factors.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of dyslipidemia in the southwest region of Iran has significant implications for public health policies. The findings of studies conducted in Iran suggest that dyslipidemia is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and that its prevalence is considerable in the population. Therefore, public health policies should focus on preventing and managing dyslipidemia to reduce the incidence of CVD and improve the overall health outcomes of the population. Public health policies should prioritize interventions that target the modifiable risk factors associated with dyslipidemia, such as unhealthy lifestyles, physical inactivity, and obesity. Additionally, raising awareness about dyslipidemia and its associated risk factors among healthcare providers and the general population is essential for the early detection and management of this condition.

Methods

Study design and participants

This population-based cross-sectional study used baseline data from 10009 individuals who participated in the Hoveyzeh Cohort Study (HCS), aged 35–70 years, between 2016 and 201833. HCS is a part of the Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study)34. Inclusion criteria consisted of individuals aged 35–70 years old, residents of Hoveyzeh, without severe mental disorders, and capable of completing the questionnaires independently. We excluded 163 pregnant women and finally, 9846 people were assessed in the analysis. Additionally, because the Framingham score evaluates the risk of developing cardiovascular disease over the next ten years, So, 1,486 individuals with cardiovascular disease were excluded only in Framingham score calculations.

Dyslipidemia: definition and quality control in the laboratory

The criteria for dyslipidemia were present in at least one of the above disorders or use of lipid-lowering medications based on the ATP III classification in adults from an individual’s lipoprotein levels, which can be determined by obtaining a complete lipoprotein profile after a 10 to 12 h fast35.

The LDL Cholesterol targets and also threshold values for implementing therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC) and drug therapy (DT) vary across different risk categories. For FRS > 20%, the Goal is LDL < 100 mg/dL, TLC should be initiated for individuals with LDL Levels of 100–129 mg/dL, and for people having LDL Levels ≥ 130 mg/dL, TLC + DT should be applied. For FRS 10–20%, the Goal is LDL < 130 mg/dL, TLC should be initiated for individuals with LDL Levels 130–159 mg/dL, and TLC + DT should be applied for people with LDL Levels ≥ 160 mg/dL). Finally in subgroup FRS < 10%, the Goal is LDL < 160 mg/dL, TLC should be initiated for individuals with LDL Levels of 160–189 mg/dL, and TLC + DT should be started for people with LDL Levels ≥ 190 mg/dL).

From each participant, 27 cc of blood was drawn. The tubes containing the blood clots were left at room temperature for 30 to 40 min before being placed in a centrifuge under a Class II laminate laboratory hood. Then, the serum was separated from the rest of the blood. Then, the clot tubes were placed in the centrifuge (Sigma, Germany) and spun at 3000 rpm for 10 to 15 min. The levels of serum required were measured using the BT 1500 autoanalyzer (Biotecnica Instruments, Italy). Normal and pathogen control serum samples were defined and tested on the BT 1500 device. The results of the control serum samples were evaluated using the Westgard and Levy Jennings quality control chart. Using this data, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. A Levy Jennings chart was created with the warning limits set at x + 2SD and the control limits set at x + 3SD. The percent coefficient of variation (CV) was determined by multiplying the SD by 100 and dividing it by the mean value of the results in a set of replicated measurements. The smaller CV indicates higher precision. The biochemical tests for Cholesterol, TG (GPO-PAP), HDL (IMMUNO), and FBS were performed using quantitative diagnostic kits from Pars Azmoun company in Iran and analyzed using the BT 1500 autoanalyzer (Biotecnica Instruments, Italy).

Data collection

Demographic variables, including age groups: 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65–70 years; sex: males and female; residence area: urban or rural; educational levels: illiteracy, primary school, secondary school, high school diploma, and university); Marital status (single, married, widow, divorced); Waist circumference (normal, abnormal); Hypertension was defined as having a systolic blood pressure equal or greater than 140 mmHg, or/and a diastolic blood pressure equal or greater than 90 mmHg, the use of antihypertensive medication, or self-reported hypertension, based on a physician’s previous diagnosis. Additionally, the physical activity score based on the metabolic equivalent task (MET) was divided into quartiles(Q1-Q4), and a smoker is defined as an individual who has consumed a minimum of 100 cigarettes throughout their lifetime (Yes, No). Furthermore, in this study, the Wealth Index utilized serves as a household’s assets. This index is calculated by considering several household factors, such as the ownership of certain assets, including televisions, bicycles, cars, computers, and so on. The calculated wealth scores were subsequently transformed into five quintiles, ranging from the poorest to the richest categories. The Framingham risk score (FRS) was utilized to evaluate the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), taking into account six coronary risk factors such as age (in years), sex (male/female), TC (in mg/dl), HDL-cholesterol (in mg/dl), systolic blood pressure (in mm Hg), and smoking habits (Yes/No). To calculate the FRS, the following thresholds were considered: TC < 160, 160–199, 200–239, 240–279, and ≥ 280 mg/dL; for systolic blood pressure: < 120, 120–129, 130–139, 140–159, and ≥ 160 mmHg; and for HDL-C: < 40, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥ 60 mg/dL. The total points determined the ten-year risk in percentage scored (1 point = 6%, 2 points = 8%, 3 points = 10%, 4 points = 12%, 5 points = 16%, 6 points = 20%, 7 points = 25%, 10 points or more > 30%). Based on the total score, the risk of CVD over ten years was categorized into three groups: low risk (< 10%), intermediate risk (10–20%), and high risk (> 20%) of developing CVD within 10 years36.

Data analysis

In Descriptive statistics, means and standard deviations for quantitative data and frequency and percent for categorical variables were applied. The Chi-square test was performed to evaluate the association between two categorical variables. The Chi-square test for trend was used to investigate the trend of dyslipidemia in ordinal variables. An independent t-test was used to assess the differences in the mean amount of lipid profiles between men and women. The logistic regression model was used to evaluate the determinants of dyslipidemia, controlling for the potential confounders. There is no consensus on the best method for selecting variables. There are two main strategies: the full model approach, which includes all candidate variables to prevent overfitting and selection bias, resulting in accurate standard errors and p-values37. It is suggested to begin with significant (p < 0. 25) and clinically relevant variables from univariable analysis for multivariable analysis38. Variables with p < 0.25 in the univariable regression analysis were entered as covariates into the multivariable logistic regression analyses. These variables were age, sex, educational level, waist circumference (WC), residence type, physical activity, smoking, wealth index, and hypertension. The population attributable fraction (PAF) is used to assess the public health impact of the exposures on the condition in the study population. The PAF is the proportion of cases for an event attributed to a defined exposure among the total population39. The unbiased estimation of PAF was conducted using a sample-weighted version of the Miettinen formula:32,39

Considering that the type of our study was cross-sectional, the adjusted odds ratio was used instead of relative risk in the formula32. Pe refers to the proportion exposed in the total population.

All the reported p-values were based on two-tailed tests and compared to a significance level of 0.05. IBM® SPSS® Statistics 24.0 was used for the statistical analysis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- HCS:

-

Hoveyzeh cohort study

- The PERSIAN Cohort Study:

-

Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran

- TLC:

-

Therapeutic lifestyle changes

- DT:

-

Drug therapy

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent task

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

References

Pappan, N. & Rehman, A. StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2022).

Opoku, S. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for dyslipidemia among adults in rural and urban China: findings from the China national stroke screening and prevention project (CNSSPP). BMC Public Health 19, 1500. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7827-5 (2019).

Gao, H. et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated risk factors among adult residents of Shenmu City, China. PLoS One 16, e0250573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250573 (2021).

Noubiap, J. J. et al. Prevalence of dyslipidaemia among adults in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e998–e1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30275-4 (2018).

Lee, Z. V. et al. Prevalence of plasma lipid disorders with an emphasis on LDL cholesterol in selected countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Lipids Health Dis. 20, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01450-8 (2021).

Shin, D. Y., Jang, Y. K., Lee, J. H., Wee, J. H. & Chun, D. H. Relationship with smoking and dyslipidemia in Korean Adults. JKSRNT 8, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.25055/JKSRNT.2017.8.2.73 (2017).

Khanali, J. et al. Prevalence of plasma lipid abnormalities and associated risk factors among Iranian adults based on the findings from STEPs survey 2021. Sci. Rep. 13, 15499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42341-5 (2023).

Organization, W. H. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. (2014).ISBN:9789241564854. URL:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564854

Garg, R., Aggarwal, S., Kumar, R. & Sharma, G. Association of atherosclerosis with dyslipidemia and co-morbid conditions: A descriptive study. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 6, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-9668.149117 (2015).

Linton, M. F. et al. The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis (MDText.com Inc, 2019).

Cho, S. M. J., Lee, H. J., Shim, J. S., Song, B. M. & Kim, H. C. Associations between age and dyslipidemia are differed by education level: The cardiovascular and metabolic diseases etiology research center (CMERC) cohort. Lipids Health Dis. 19, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-020-1189-y (2020).

Liu, H. H. & Li, J. J. Aging and dyslipidemia: A review of potential mechanisms. Ageing Res. Rev. 19, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.12.001 (2015).

Shafiee, A. et al. Epidemiology and prevalence of dyslipidemia among adult population of tehran: the tehran cohort study. Arch. Iran. Med. 27, 51–61 (2024).

Soriano-Maldonado, C. et al. Gender differences in the diagnosis of dyslipidemia: ESCARVAL-GENERO. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 12419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312419 (2021).

Chehrei, A., Sadrnia, S., Keshteli, A. H., Daneshmand, M. A. & Rezaei, J. Correlation of dyslipidemia with waist to height ratio, waist circumference, and body mass index in Iranian adults. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 16, 248–253 (2007).

Esteghamati, A. et al. Third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases (SuRFNCD-2007) in Iran: methods and results on prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, central obesity, and dyslipidemia. BMC Public Health 9, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-167 (2009).

Moradinazar, M. et al. Association between dyslipidemia and blood lipids concentration with smoking habits in the Kurdish population of Iran. BMC Public Health 20, 673. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08809-z (2020).

Nakamura, M. et al. Relationships between smoking status, cardiovascular risk factors, and lipoproteins in a large japanese population. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 28, 942–953. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.56838 (2021).

Jeong, W. Association between dual smoking and dyslipidemia in South Korean adults. PLoS One 17, e0270577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270577 (2022).

Banitalebi, M., Babak, A., Rouzbahani, R. & Motlagh, R. K. N. Nutrition and physical activity in Iranian dyslipidemic patients. Acta Med. Iran. https://doi.org/10.18502/acta.v57i10.3247 (2019).

Hajian, S. et al. The relationship between dyslipidemia and disease activity in Iranian population with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Nephropharmacol. 8, e06–e06 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Association between health-related physical fitness and risk of dyslipidemia in university staff: A cross-sectional study and a ROC curve analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010050 (2021).

Muscella, A., Stefàno, E. & Marsigliante, S. The effects of exercise training on lipid metabolism and coronary heart disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 319, H76–H88. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2019 (2020).

Maciel, E. D. S. et al. Physical inactivity level and lipid profile in traditional communities in the legal Amazon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 22, 542. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12973-9 (2022).

Espírito Santo, L. R. et al. Socioeconomic status and education level are associated with dyslipidemia in adults not taking lipid-lowering medication: a population-based study. Int. Health 14, 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihz089 (2019).

Lara, M. & Amigo, H. Association between education and blood lipid levels as income increases over a decade: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 18, 286. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5185-3 (2018).

Gebreegziabiher, G., Belachew, T., Mehari, K. & Tamiru, D. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated risk factors among adult residents of Mekelle city Northern Ethiopia. PLoS One 16, e0243103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243103 (2021).

Kumma, W. P. & Loha, E. Dietary patterns and their association with cardiovascular risk factors in Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 10, 1074296 (2023).

Miao, C. Y. et al. Association between dyslipidemia and antihypertensive and antidiabetic treatments in a China multicenter study. J. Clin. Hypertens. 23, 1399–1404 (2021).

Dalal, J. J. et al. LIPITENSION: Interplay between dyslipidemia and hypertension. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 16, 240–245. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.93742 (2012).

Wyszyńska, J., Łuszczki, E., Sobek, G., Mazur, A. & Dereń, K. Association and risk factors for hypertension and dyslipidemia in young adults from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20020982 (2023).

Khosravi, A. & Mansournia, M. A. Recommendation on unbiased estimation of population attributable fraction calculated in” prevalence and risk factors of active pulmonary tuberculosis among elderly people in China: a population based cross-sectional study". Infect. Dis. Poverty 8, 82–84 (2019).

Cheraghian, B. et al. Cohort profile: The hoveyzeh cohort study (HCS): A prospective population-based study on non-communicable diseases in an Arab community of Southwest Iran. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran 34, 141. https://doi.org/10.34171/mjiri.34.141 (2020).

Poustchi, H. et al. Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): rationale, objectives, and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 647–655 (2018).

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 285, 2486–2497 (2002).

Sohn, C., Kim, J. & Bae, W. The framingham risk score, diet, and inflammatory markers in Korean men with metabolic syndrome. Nurs. Res. Pract. 6, 246–253 (2012).

Royston, P., Moons, K. G., Altman, D. G. & Vergouwe, Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ 338, b604 (2009).

Hosmer, D. W., Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R. X. Applied Logistic Regression (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Mansournia, M. A. & Altman, D. G. Population attributable fraction. BMJ 360, k757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k757 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Hoveyzeh Cohort Study Center who assisted us in conducting this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Vice-Chancellor for Research at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences [Grant Number HCS-0007]. The Vice-Chancellor for Research at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences as our funding body played no role in the design of the study and gathering, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZR conceptualized the idea. BCh prepared the design and research instrument. ZR, MR performed the data collection and processing. ZR and BCh carried out data analysis and were a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. NS, SAH, BCh, SS and SJH interpreted the research data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The ethics committee approved the study protocol of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.AJUMS.REC.1400.616). This study was conducted based on the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. On the registration day, informed written consent was obtained from the study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheraghian, B., Saki, N., Sarvandian, S. et al. Evaluation of dyslipidemia based on ATP III guideline in adults in Southwest Iran: a population-based study. Sci Rep 15, 9463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90141-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90141-w