Abstract

X-ray inspection is a crucial technique for identifying defects in castings, capable of revealing minute internal flaws such as pores and inclusions. However, traditional methods rely on the subjective judgment of experts, are time-consuming, and prone to errors, which negatively impact the efficiency and accuracy of inspections. Therefore, the development of an automated defect detection model is of significant importance for enhancing the scientific rigor and precision of casting inspections. In this study, we propose a deep learning model specifically designed for detecting small-scale defects in castings. The model employs an end-to-end network architecture and features a loss function based on the Wasserstein distance, which is tailored to optimize the training process for small defect targets, thereby improving detection accuracy. Additionally, we have innovatively developed a dual-layer Encoder-Decoder multi-scale feature extraction architecture, BiSDE, based on the Hadamard product, aimed at enhancing the model’s ability to recognize and locate small targets. To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we conducted a series of experiments, including comparative tests with current state-of-the-art object detection models such as Yolov9, FasterNet, Yolov8, and Detr, as well as ablation studies on the model’s components. The results demonstrate that our model achieves at least a 5.3% improvement in Mean Average Precision (MAP) over the existing state-of-the-art models. Furthermore, the inclusion of each component significantly enhanced the overall performance of the model. In conclusion, our research not only validates the effectiveness of the proposed small-scale defect detection model in improving detection precision but also offers broad prospects for the automation and intelligent development of industrial defect inspection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the metal casting process, influenced by various factors such as materials, techniques, and equipment, castings often exhibit a range of defects that significantly undermine their performance and lifespan1. These defects primarily include porosity, inclusions, shrinkage and looseness, cold shuts, and cracks2. Each type of defect can lead to a reduction in mechanical performance, diminished corrosion resistance, shortened service life, increased machining difficulty, and elevated safety risks. Therefore, the detection and quality control of casting defects are crucial for ensuring the quality and safety of the castings3.

X-ray inspection, as one of the primary non-destructive testing methods for casting defects4,5, demonstrates unique advantages due to its ability to penetrate metallic materials and clearly reveal internal structures. However, this method requires operators to possess a high level of professional skills, which not only increases labor costs but also complicates defect detection due to potential confusions in the images—especially when defects are minute or resemble the surrounding material texture, thereby increasing the difficulty of detection and risk of misinterpretation. Therefore, the development of a fully automated system capable of accurately identifying small target defects is of critical importance. Traditional detection methods, such as those based on image sequences and wavelet transform, although widely used, often face issues of insufficient accuracy and poor model generalization capabilities6,7.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence8. Utilizing deep learning technology to automatically recognize and accurately differentiate minute defects9 not only significantly enhances the accuracy and efficiency of detection but also helps to reduce labor costs and improve the level of automation in production. D Mary and colleagues achieved significant results by constructing 3D ellipsoid models and using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to collect data, followed by training with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)10. Additionally, S Kumaresan and colleagues employed an adaptive transfer learning approach with the VGG16 network for fine-tuning, aimed at classifying weld defects in X-ray images, demonstrating good generalization performance across 15 different categories11. With the development of end-to-end architecture networks, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) model has garnered significant attention due to its ability to perform fast and accurate real-time object detection, showing substantial potential in industrial visual inspection applications12. Wu and colleagues developed a simple, fast, and high-precision automated system for internal defect recognition using the YOLO architecture13. While these studies have significantly improved the detection performance of traditional casting models, issues such as insufficient model interpretability, low data quality, and the need to improve the accuracy of detecting minute defects remain prevalent.

Based on the aforementioned background, this paper specifically establishes a dataset for deep learning, dedicated to the defect detection and recognition of X-ray casting images, with a particular focus on enhancing the accuracy of the model when detecting small target defects. We innovatively improved the traditional Ciou14 loss to NWD (Normalized Wasserstein Distance) loss15, aiming to achieve more accurate loss values for small targets. Inspired by the feature extraction methods of the YoloV8 model and the Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BIFPN)16, we constructed a novel point-to-point multi-scale feature extraction architecture—BiSDE (Bi-directional Small Object Detail Enhancement). This architecture promotes the flow of information between different levels and sizes of targets through skip connections. Simultaneously, enhanced small target detail features are integrated into each layer of the feature map using the Hadamard product method. The overall workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Workflow diagram of the YOLO-BiSDE framework, integrating the NWD Loss Detailed mathematical definitions can be found in Section "Normalized Wasserstein distance Loss".

In summary, the main innovations of this work are as follows:

-

We have specifically constructed a dataset comprising over 1,300 images for the detection of small-scale X-ray casting defects. This dataset has undergone meticulous preprocessing, including cropping, denoising, and filtering, before being annotated. Our aim is to accurately detect small defects in X-ray images.

-

To address the challenge of small object detection, we have improved detection accuracy by utilizing the Normalized Wasserstein Distance. Additionally, we have enhanced inter-level information exchange through the use of skip connections. On this basis, we further strengthen the point-to-point detail fusion of different feature maps using Hadamard product.

-

We conducted detailed ablation and comparative experiments. In the comparative experiments, we compared our model with the current state-of-the-art models, demonstrating that our model achieved the best performance. In the ablation experiments, we incrementally integrated each component into the model to validate their effectiveness. The experimental results show that each proposed component significantly enhances the model’s performance, with the final model surpassing the current state-of-the-art object detection models by at least 5.8%.

-

Normalized Wasserstein Distance Loss is an innovative regression loss function designed to address the challenges of small object detection. Unlike traditional loss functions such as IoU and its variants, which focus solely on the overlap between predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes, NWD Loss models the discrepancy between the predicted and ground-truth boxes using Gaussian distributions. By minimizing the Wasserstein distance between the predicted and ground-truth distributions, NWD Loss achieves more precise and robust alignment of bounding boxes. This advantage is particularly significant in scenarios involving small objects, where slight deviations in bounding box coordinates can substantially impact detection performance. Consequently, NWD Loss has demonstrated exceptional effectiveness in improving the accuracy of detecting small defects in X-ray images.

Related work

Casting defect detection and identification

In the field of casting defect detection and identification, related work primarily encompasses several methods17:

Adaptive filtering based on structure

Klatte utilized a specific filter to process each integrated X-ray image x, ensuring that the filter’s mask distribution matches the projected structure of the test piece at the inspection position18. By calculating the difference between the integrated image x and the estimated defect-free image y, defects are identified, though the limitations of the filter design cannot be avoided. Heinrich and his team developed a median filter that, by employing an adaptive filtering mask design, effectively suppresses small-scale structures while preserving certain features of larger structures. However, the consistency of the filtering effects cannot be guaranteed19,20.

Methods using machine learning, independent of the test piece’s position and structure

Santos et al. proposed a machine learning algorithm that applies Bayesian Networks and K-Nearest Neighbors, achieving promising results in the field of image classification for casting defects21. Wu et al. tested various combinations of feature engineering and machine learning algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests. They ultimately concluded that Local Binary Pattern (LBP) features and ensemble learning yielded the optimal results22. Iker Pastor-López et al. detected surface defects using segmentation methods and subsequently classified casting defects using machine learning classifiers such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Support Vector Machines (SVM)23. The aforementioned methods, while improving accuracy compared to traditional filtering techniques, still present several issues. These include high computational complexity, an inability to accurately localize defect positions in image classification, and a high dependence on image quality and preprocessing.

Techniques involving computer tomography scanning

Feid et al. proposed an automated defect recognition method based on 3D computer tomography (CT) scanning and Random Forest classifiers24. Nicoletto, G. and his team utilized CT scanning technology to analyze porosity and intermetallic phases in high-pressure die-cast Al–Mg-Si-Mn alloys25. In addition to the aforementioned studies, the application of CT scanning technology for defect detection in industrial castings remains widespread26,27,28,29,30. However, this method has the limitation of longer scanning times. Compared to other imaging techniques, CT scanning may require more time to obtain high-resolution three-dimensional images. This is particularly significant in the context of large-scale production, as each workpiece needs to be scanned individually, potentially leading to decreased production efficiency. Additionally, the operation of CT scanning equipment is relatively complex, typically requiring specially trained personnel for operation and maintenance. This not only increases the operational difficulty but may also result in additional training and labor costs.

End-to-end artificial intelligence automatic recognition methods

With the advancement of deep learning technology, end-to-end artificial intelligence (AI) automatic recognition methods have achieved promising results in the field of defect detection in castings. End-to-end AI automatic recognition refers to a system where the entire process, from data input to the final recognition result, is completely automated by an AI model. Its advantages lie in its high degree of automation and integration, enabling it to handle complex recognition tasks efficiently31. Q et al. proposed an improved end-to-end casting surface defect detection network based on Detr, which demonstrates higher speed but lacks attention to small targets32. Zhong et al. proposed a YOLO-based method for metal surface defect detection, achieving state-of-the-art performance by designing a cross-scale shallow feature enhancement approach combined with pooling attention mechanisms, demonstrating strong generalization capabilities33. Some recent state-of-the-art studies have focused on the lightweight implementation of defect recognition. These works leverage deformable convolutions and feature compression modules to effectively reduce information loss. Additionally, by employing methods that adapt to changes in feature scales, they enhance the distinctiveness of semantic features associated with defects, thereby improving both the reliability and speed of defect detection. Experimental results demonstrate that these approaches achieve competitive performance while attaining SOTA-level lightweight metrics34.

Small defect detection

Defect detection research has increasingly emphasized the challenges posed by surface defects, particularly in industrial applications. Recent advancements have introduced state-of-the-art (SOTA) models employing innovative two-stage detection frameworks. Initially, data augmentation techniques are leveraged to enhance the diversity and robustness of training datasets. This is followed by feature extraction using ResNet-101, which is further enriched through a feature pyramid structure to address the complexity of multi-scale defect detection. An improved Region Proposal Network (RPN) plays a pivotal role in accurately identifying defect regions, specifically focusing on the detection of missing small fasteners, such as pins, bolts, and rivets, in freight train systems. By incorporating a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN), the approach refines the segmentation of defect areas, ensuring precise localization. These developments underline the model’s potential for achieving exceptional performance in identifying small-scale defects, offering significant value for industrial quality control and safety assurance35.

In addition, some studies, such as the work by Xu et al. have primarily focused on feature extraction techniques for small targets in surface defects of castings. However, there is still a lack of in-depth analysis regarding the challenges in identifying small targets inside castings36. Similarly, other studies, such as the research conducted by Li et al., have concentrated on developing detection frameworks for small surface defects in industrial components. Nevertheless, the specific challenges associated with detecting small internal defects within these components remain underexplored and require further investigation37. Therefore, this study focuses on utilizing X-ray imaging technology for small target detection of internal defects, aiming to address the gaps in existing research and provide technical support for more comprehensive industrial defect detection.

Our proposed model focuses on detecting internal defects in small castings under X-ray inspection. We delve into the inherent challenges of identifying small targets and design a solution based on this analysis. The following Section "Methodology" elaborates on the methods we employed, while Section "Experiments" is dedicated to the experimental design and analysis of the results. Finally, the overall discussion is presented in the concluding section.

Methodology

Data collection

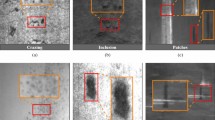

The training data for this study were collected using the XR225F model X-ray real-time imaging defect detection device. The configuration of the data collection device is depicted in Fig. 2, where we gathered defect images of X-ray castings in three batches over a period of 72 h. The equipment incorporates a computer, monitor, controller, and a 27-inch digital monitor; for detailed specifications, refer to Fig. 2. Through this X-ray device, we collected over 1500 images. After filtering out images that did not meet the quality standards, 1068 images were retained. These images were manually annotated by experts, labeling them under the “defect” category. The resolution of the dataset was uniformly set at 768 × 512 pixels, and data augmentation processes were applied prior to training. Data augmentation procedures were performed before training, and the dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing sets with a ratio of 7:1:2, respectively.

Data preprocessing

To enhance the adaptability and robustness of our model in real-world scenarios, we implemented a series of advanced image augmentation techniques on our training data. For examples of data and details on the data augmentation, see Fig. 3, These techniques include:

-

HSV Transformation38: Minor random adjustments are made to the hue, saturation, and brightness of images to enhance their color expressiveness and adaptability.

-

Mixup39 This method creates new samples by taking the weighted average of two different images, effectively reducing overfitting and improving the model’s ability to discriminate between class boundaries.

-

Mosaic40 By combining four different images into one, this technique allows the model to better understand and process scenes containing multiple objects and complex backgrounds.

-

Random perspective Random perspective transformations are applied to simulate image deformations from various viewpoints, enhancing the model’s capacity to adapt to changes in perspective.

Model construction

In constructing the backbone layer of the model, we adopted the YOLOv8 backbone architecture and integrated the Bi-directional Small Object Detail Enhancement (BiSDE) and NWDLOSS. The detailed network architecture, including the BiSDE-Decoder module and BiSDE-Encoder module, is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Normalized Wasserstein distance Loss

In object detection tasks, the loss function employed by YOLOv8 demonstrates its capability and flexibility in handling targets of varying sizes. The classification loss utilizes binary cross-entropy, primarily aimed at verifying the accuracy of the predicted categories. Simultaneously, the regression loss is calculated using the CIoU (Complete Intersection over Union) loss41, which evaluates the accuracy of predictions by measuring the distance between the centers of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, while also incorporating changes in aspect ratio.

Motivation for designing NWDLOSS

Although some loss functions, such as CIoU, perform well in detecting medium to large objects, they exhibit certain limitations when handling small objects, such as defects in X-ray castings. In small-object detection scenarios, even minor discrepancies between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes can lead to a significant drop in IoU values, negatively affecting the overall performance of the model. Small-object detection requires higher localization precision and boundary prediction accuracy, which traditional CIoU may struggle to effectively handle in these highly sensitive scenarios. To address these challenges, we propose the Normalized Wasserstein Distance-based loss function (NWDLOSS). The motivation for designing NWDLOSS is based on the following considerations:

-

Improved detection precision NWDLOSS evaluates the differences between bounding boxes using the Wasserstein distance, which captures geometric relationships between bounding boxes more accurately than traditional IoU metrics.

-

Handling high-sensitivity scenarios IoU-based loss functions, which heavily rely on the overlap between bounding boxes, NWDLOSS demonstrates greater robustness in small-object scenarios. It provides stable gradient flow, thereby improving the training process and ensuring consistent performance.

Comparison between different loss functions and NWDLOSS

As shown in Table 1, the differences between various loss functions and NWDLOSS are outlined to highlight the advantages of NWDLOSS. This comparison demonstrates how NWDLOSS addresses the limitations of traditional loss functions and provides superior performance in small-object detection scenarios. The compared loss functions primarily include commonly used ones in object detection, such as CIoU, IoU, DIoU, and GIoU.

NWDLOSS’s specific mathematical principles and implementation: The Central Limit Theorem posits that for a large number of independent42, identically distributed random variables, regardless of the original distribution of individual measurements, the distribution of their sum (or average) will tend towards a Gaussian distribution as the sample size increases. Within the context of bounding boxes, if parameters such as coordinates \(x,y\) and dimensions \(w,h\) are considered as random variables, the averages of these parameters across many bounding boxes will approximate a Gaussian distribution.

Assuming \(P\) and \(T\) represent the parameters derived from a large sample of predicted and actual bounding boxes, according to the Central Limit Theorem, the distributions of their mean coordinates and sizes will approach Gaussian distributions. Thus, \(P\) and \(T\) can be described as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2).

Here, \({\mu }_{P}\) and \({\mu }_{\text{T}}\) represent the mean vectors of the bounding box centers, and \({\Sigma }_{P}\) and \({\Sigma }_{\text{T}}\) represent the covariance matrices related to the size and shape variations of the bounding boxes. Specifically, for a complete bounding box, the definition of the mean vector is provided in Eq. (3).

To measure the discrepancies between two small object bounding boxes, we employ the Wasserstein distance expressed through Gaussian distributions. The computation of the multi-dimensional Wasserstein distance is illustrated in Eq. (4)43. For the Gaussian distributions \(P\) and \(T\), the Wasserstein distance has a closed-form solution, which can be expressed as shown in Eq. (5). The term \({inf}_{\gamma \in \prod \left(P,T\right)}\) represents the infimum over all possible joint distributions γ that have \(P\) and \(T\) as their marginal distributions.

To ensure that the range of the loss function values is more appropriate for the training process, an exponential form is used to mitigate large gradient values or other numerical issues, with ε serving as a scaling factor. The final loss function is expressed as shown in Eq. (6). Additionally, we present the pseudocode for the NWD Loss, specifically including the method for obtaining the Wasserstein distance, as shown in Table 2.

Bi-directional small object detail enhancement

To improve the detection of small objects, in addition to designing a specialized loss function, we developed a feature extraction network called Bi-directional Small Object Detail Enhancement (BiSDE), which incorporates various refined detail processing techniques. BiSDE employs an Encoder-Decoder architecture. In the Encoder part, it captures more useful information at different spatial levels through a hierarchical feature extraction approach. In the Decoder part, it effectively utilizes the Hadamard product to facilitate the flow of information across multiple feature map levels. The proposed BiSDE architecture comparison is shown in Fig. 5.

The four feature extraction methods, FPN, PANet, NAS-FPN, and BiSDE44,45,46, are shown respectively. Compared to the BiSDE feature processing layer proposed in this study, traditional FPN and PANet utilize simple top-down or bottom-up network architectures, lacking complex cross-level connections and feature exchange mechanisms. This limitation weakens their ability to capture relationships between features at different levels. The improved NAS-FPN can capture cross-level features; however, its architecture includes some redundant paths that do not significantly contribute to performance enhancement, and its feature processing approach is relatively monotonous.

Encoder

Inspired by the Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN), our designed encoder utilizes both top-down and bottom-up pathways for feature fusion, a structure that ensures efficient transmission of information across different scales and levels. Additionally, we have established connections between various levels to further promote the integration of features. To prevent the emergence of redundant paths and to optimize feature fusion efficiency, we have introduced a weighted feature fusion method that allows the network to autonomously learn the importance of features on each path. For any potential feature fusion node \({\text{P}}_{\text{i}-1}\), \({\text{P}}_{\text{i}+1}\), \({\text{P}}_{\text{i}}^{^{\prime}}\), where these directions represent:

-

1.

\({\text{P}}_{\text{i}-1}\): Features from the next lower layer, adjusted to the current node iii scale through an upsampling operation.

-

2.

\({\text{P}}_{\text{i}+1}\): Features from the previous higher layer, adjusted to the node iii scale through a downsampling operation.

-

3.

\({\text{P}}_{\text{i}}^{^{\prime}}\) : Intra-level feature transmission within the current layer.

Feature fusion can be represented as shown in Eq. 7. Wherein \({\text{w}}_{1}\), \({\text{w}}_{2}\), and \({\text{w}}_{3}\) are learnable weights that control the contributions of features from different sources during the fusion process.

By adopting this approach in the encoder architecture of the feature extraction layer, on one hand, it allows for the elimination of redundant pathways, thereby accelerating the model’s convergence speed. On the other hand, given that the internal defects in castings are typically small and distinctly localized, this design significantly enhances the attention to features of small targets.

Decoder

The primary function of the decoder is to sequentially upsample the feature maps of casting defects processed by the encoder and fuse them using the Hadamard product to reconstruct the details and spatial information of the targets. This process aims to generate the final feature maps used for defect detection. The specific implementation principles of the decoder are illustrated in Fig. 6.

In the context of three feature maps of varying sizes, denoted as L1, L2, and L3, spatial and channel attention mechanisms are employed within their respective layers to perform associative analysis across both the channel and spatial dimensions. Given the feature map \({F}_{{L}_{1}}\in {R}^{c\times H\times W}\), the spatial attention mechanism integrates the features derived from global average pooling and max pooling to focus on prominent small-object features beyond mere average information. The expression for spatial attention is presented as Eq. 8.

The implementation of global average pooling and global max pooling are represented by \({\text{F}}_{\text{avg}}^{\text{c}}\) and \({\text{F}}_{\text{max}}^{\text{c}}\), respectively, as shown in Eqs. 9 and 10.

For channel attention, the weights of different channels are computed through the fully connected layers \({F}_{{C}_{1}}\) and \({F}_{{C}_{2}}\), selecting the most suitable channels to participate in feature extraction, as presented in Eq. 11.

Ultimately, spatial and channel attention mechanisms are applied within the feature map, as denoted by Eq. 12.

In the feature maps processed through channel and spatial attention mechanisms, the first step involves normalizing the number of channels to ensure consistency in the channel dimensions across different layers. Specifically for the \({F}_{{L}_{1}}^{C\&S}\) layer, the dimensions of all other layers, except \({F}_{{L}_{1}}^{C\&S}\), are adjusted to match the dimensions of \({F}_{{L}_{1}}^{C\&S}\). After this dimension adjustment, the aligned feature maps undergo smoothing operations to reduce noise and discontinuities, thereby further enhancing the quality of the feature maps.

Following the smoothing process, the Hadamard product is employed to merge all adjusted and smoothed feature maps. This method facilitates the thorough integration of features across layers, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to capture details and improving its resolution, as detailed in Eq. 13.

The feature extraction network BiSDE developed by our institute is specifically optimized for small object detection. This network adopts a bidirectional path encoder structure (top-down and bottom-up) to ensure effective information transfer across different scales. Additionally, by introducing weighted feature fusion technology, the network not only maximizes the efficiency of feature utilization but also significantly reduces redundant paths. In the decoder section, the combination of spatial and channel attention mechanisms, along with sequential upsampling and the application of the Hadamard product, effectively reconstructs detailed spatial information, thereby improving the quality and accuracy of the final feature maps.

Model evaluation

The evaluation metrics employed in this study include Precision, Recall, F1-Score, Frames Per Second (FPS), and mean Average Precision (mAP). Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all predicted positive instances, reflecting the model’s accuracy in identifying positive samples. Recall assesses the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances out of all actual positive instances, indicating the model’s ability to capture relevant cases. The F1-Score provides a balanced metric that considers both Precision and Recall, offering a single measure of the model’s performance. Mean Average Precision (mAP) evaluates the detection performance across all categories, serving as a comprehensive assessment of model accuracy. Frames Per Second (FPS) represents the number of images processed by the model per second, reflecting the model’s efficiency in real-time scenarios. In this study, FPS is particularly important to ensure that improvements in accuracy do not come at the expense of processing speed. These metrics collectively provide a holistic evaluation of the model’s performance.

Experiments

Experiment setup

In our experimental process, we conducted a series of tests to validate the model’s performance. First, we compared the performance of different network architectures to assess the superiority of our model. Next, we incrementally added components to validate the effectiveness of the NWD loss and the Encoder-Decoder of BISDE, and demonstrated the relationship between accuracy and efficiency through FPS values. Additionally, we conducted visualization and analysis. All models were iterated multiple times until they reached a stable state without overfitting. The experiments employed five-fold cross-validation, and the performance metrics from five experiments were averaged to provide an overall performance assessment of the model.

During the pretraining process, we utilized publicly available weights that had been pretrained on the large-scale public dataset COCO, and fine-tuned the model on the defect detection task. We optimized the feature extraction layers and adjusted the hyperparameters based on the literature to tailor the model to the specific requirements of the current task. During fine-tuning, only the later layers were trained, preserving the general features learned from the pretrained model, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability and generalization ability.

The hyperparameter and experimental platform settings are detailed in Table 3. The primary task involves binary classification for defect detection and recognition, with the classes labeled as Defect and Non-Defect. Each parameter setting is based on preliminary tests and existing literature.31,32,33.

Comparison with baseline model

In the comparative experiments, we conducted detailed analyses of different models. The models used for the comparative experiments are as follows:

-

YOLO Series [YOLOv5-YOLOv9] Due to their end-to-end network architecture and efficient, rapid object detection capabilities, the YOLO series has found widespread application in the field of computer vision. Particularly after YOLOv8, the highly integrated code structure makes it exceptionally suitable for engineering applications.

-

FasterNet47 Through multi-scale feature extraction and a lightweight network architecture, FasterNet ensures high inference speed while maintaining high accuracy. It is a classic network that balances both precision and speed effectively.

-

DETR48 DETR utilizes a Transformer architecture to achieve an end-to-end task framework, simplifying the post-processing steps. It demonstrates significant advantages in small object detection and casting defect recognition.

The comparative experiment results are shown in Table 4. All models were trained using a five-fold cross-validation strategy and were iterated until they reached a stable state with no overfitting observed.

In the selection of the base model, this study is strongly supported by comparative experimental results. Besides our proposed model, YOLOv8 exhibited the best performance. Therefore, our BISDE model is based on YOLOv8 for both the ENCODER-DECODER part and the establishment of NWD-loss. This is likely due to YOLOv8 being specifically optimized for engineering applications, enhancing its generalization capability in the engineering field, and thus elevating its performance ceiling, even surpassing the newly introduced YOLOv9 object detection model.

Through comparative experimental results, it is evident that our model achieves the highest performance in terms of Precision and Recall, with specific values exceeding 0.9. Additionally, the F1-score, which balances these two metrics, is also the highest, surpassing the second-place YOLOv8 by more than 4.8%. This indicates that our model excels in both precision and recall, effectively accomplishing the relevant tasks. Interestingly, the Precision values for all models are more than 1.25% higher than their Recall values. This reflects a limitation of the models when dealing with small target tasks: for small targets with distinct features, once detected, they can be accurately predicted, but it is challenging to comprehensively detect targets with less distinct features, resulting in higher Precision than Recall. Our model’s parameter results confirm its superior performance in small target detection, with both Precision and Recall being the highest and nearly equal, demonstrating its robustness in ensuring consistent detection performance regardless of the target’s feature distinctiveness.

The MAP (Mean Average Precision) metric is used to assess the overall performance of a model, but it needs to be considered in conjunction with FPS (Frames Per Second). Even if a model achieves a high MAP, if it results in significant computational overhead, its practical value in engineering applications may be limited. Our proposed network model maintains the highest MAP without a significant decrease in FPS. Specifically, compared to the YOLOv5 model, which has the highest FPS, our model achieves a 26% increase in MAP with only a 10% reduction in FPS. When compared to the YOLOv8 model, which has the highest MAP aside from ours, our model shows a 5% increase in MAP with only a 3.9% decrease in FPS. In terms of both model speed and accuracy, our proposed BiSDE feature extraction architecture and specially optimized NWD loss function strike a balance between performance and efficiency, offering excellent practical value in the field of engineering manufacturing, particularly in the detection of casting defects.

Additionally, we plotted the variation in MAP (Mean Average Precision) over 150 epochs as the model converged to stability, as shown in Fig. 7. Specifically, we plotted the PR curve to demonstrate the model’s classification ability in the context of object detection, as shown in Fig. 8. Our model demonstrated the fastest convergence speed and achieved the highest MAP values, further illustrating the superior accuracy and efficiency of our approach in detecting small target casting defects. This highlights the enhanced performance of our solution in terms of both precision and computational efficiency.

Comparison with SOTA Model

To further validate the innovation and effectiveness of the proposed model, particularly in comparison with recently introduced state-of-the-art (SOTA) YOLO-based defect detection models, we conducted an in-depth comparison with the following approaches:

-

STEF-Net: A multi-stage approach aimed at enhancing statistical texture features in metal surface defect detection33.

-

LiFSO-Net: A lightweight feature screening optimization network designed for complex-scale metal surface defect detection34.

-

YOLOv8-m: One of the mainstream YOLO series object detection models, known for its balanced trade-off between speed and accuracy.

The comparisons were conducted on three datasets: NEU-DET, GC10-DET, and a custom X-ray casting defect detection dataset. The results of the comparison are presented in Table 5.

-

NEU-DET On the NEU-DET dataset, the proposed model achieved a MAP@50 of 81.7%, ranking second only to STEF-Net (82.3%) while significantly outperforming YOLOv8-m (77.4%). Moreover, the parameter count of the proposed model is only 12.14 M, which is lower than that of STEF-Net (19.07 M), demonstrating a superior lightweight design.

-

GC10-DET On the GC10-DET dataset, the proposed model exhibited performance comparable to LiFSO-Net, with MAP@50 scores of 71.1% and 71.2%, respectively, reflecting slightly inferior surface defect detection capability compared to the SOTA model. However, the proposed model achieved an improvement of approximately 2.8% over YOLOv8-m (68.3%). Although the parameter count is slightly higher than LiFSO-Net’s 1.77 M, the proposed model strikes a better balance between performance and lightweight design.

-

Custom X-ray casting defect dataset On the custom X-ray casting defect detection dataset, the proposed model achieved the best detection performance with a MAP@50 of 93.5%, surpassing both LiFSO-Net (89.3%) and STEF-Net (91.1%). Furthermore, the proposed model demonstrates an excellent trade-off between performance and parameter count, maintaining a parameter count of 12.14 M, which is lower than STEF-Net’s 19.07 M. This further validates the model’s innovation and effectiveness.

The above comparisons were based on SOTA models and AI algorithms specifically designed for steel defect detection. For the task of detecting internal X-ray defects in castings, we reproduced the architectures of LiFSO-Net and STEF-Net. Since parameter counts are independent of the dataset, their reference values were primarily derived from existing literature and experimental results. Experimental results reveal that while the proposed model does not surpass the SOTA models in all metrics for surface defect detection tasks, it demonstrates strong generalization capability, achieving a satisfactory balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Moreover, the proposed model achieved the best MAP@50 performance in the task of detecting internal X-ray defects in castings. This indicates that the proposed model not only exhibits innovation and effectiveness in X-ray target detection of internal defects in castings but also validates its cross-domain generalization capability.

Ablation experiment

In addition to the comparative experiments, we also conducted ablation experiments. The setup for the ablation experiments was consistent with that of the comparative experiments, and all models were evaluated using fivefold cross-validation. The aim of the ablation experiments was to provide a more intuitive and accurate understanding of how the configuration of each model component influences overall performance trends. The results of the ablation experiments are shown in Table 6.

In Table 6, the Baseline refers to the feature extraction layer using Yolov8. The rationale for selecting Yolov8 as the Baseline is discussed in the comparative experiments. We incrementally integrate various components into the model, with BiSDE-E serving as the Encoder architecture, utilizing a top-down and bottom-up hybrid feature extraction approach. Meanwhile, BiSDE-D functions as the Decoder architecture, employing the Hadamard product method.

The results of the ablation experiments demonstrate that each component tested effectively enhances the model’s performance, with each exhibiting distinct positive effects. For instance, the NWD Loss increased the model’s Recall by 4.1%, indicating its effectiveness in improving the recall rate for small target casting defect detection and underscoring the utility of components designed for small targets. Additionally, both the Encoder and Decoder parts of the BiSDE architecture significantly boosted the model’s MAP value. The final ablation experiment results show an improvement of 5.4% in MAP value compared to the Baseline, illustrating that the BiSDE feature extraction method we developed performs effectively across different scales.

Specifically, to determine the optimal ratio between NWD Loss and traditional loss, we conducted experiments focusing on the NWD Loss parameter A. The formula for parameter A is shown below. The results of the NWD Loss parameter selection experiments are presented in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, in the ablation study, the NWD Loss component was the first to be added to the baseline model. Through multiple experiments, we determined the optimal ratio of NWD loss and then continued the ablation experiments. Ultimately, we selected a ratio of 60% NWD loss and 40% CIOU loss, at which point all model parameters achieved their optimal state. Additionally, Fig. 9 illustrates the changes in the model’s MAP as each component is added during the ablation study. The figure clearly shows that as more components are integrated, the model’s convergence speed significantly improves, and each component contributes positively to the overall model performance.

Visualization analysis

To further demonstrate the performance of the models, this study presents the inference results from both comparative and ablation experiments in Fig. 10. These visualizations display the model outputs under various conditions, clearly highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. Additionally, we used heatmaps to present the model results, providing interpretable visual analysis that emphasizes the robustness and performance of the models across different scenarios.

As seen in Fig. 10a,b, our model demonstrates superior performance in both the comparative and ablation experiments. Figure 10a shows the inference results from the comparative experiment, where our model exhibits a significant advantage in detection accuracy compared to other models, as evidenced by the confidence scores in all three images. Each image achieved a high level of confidence, and no instances of false positives or false negatives were observed throughout the detection process, further validating the robustness and reliability of our model.

Figure 10b presents the results of the ablation experiments, where the confidence scores displayed above the detection boxes further confirm the effectiveness of each component in enhancing the overall model performance.

To provide a deeper insight into the model’s feature extraction capabilities in the task of casting defect detection, we conducted a multi-stage visualization analysis of the feature extraction process within the BiSDE architecture and encoder components. Through the hierarchical display of feature maps (as shown in Fig. 11), we observed the variations in the model’s features at different depths, summarized as follows:

Stage 1 (Initial Stage) At Stage 1, the feature maps exhibit the highest resolution, clearly capturing the fine details and texture characteristics of casting defects. These feature maps focus on extracting small target information from the input images, such as the edges of tiny defect regions and subtle texture variations, demonstrating a strong capability for fine-grained feature extraction. This indicates that at the initial stage of information processing, the BiSDE architecture is capable of performing high-fidelity feature capture on the input images, laying a solid foundation for subsequent layers of information processing.

Stage 5 (Shallow Stage) In Stage 5, the feature maps maintain relatively high resolution. However, compared to Stage 1, more edge information and mid-scale structural features begin to emerge. At this stage, the feature maps gradually evolve towards multi-scale fusion, effectively integrating fine-grained details with local structural features. This significantly enhances the model’s preliminary modeling capability for complex defects. Notably, in small target detection tasks, the feature maps at this stage demonstrate that the skip connection mechanism in the BiSDE architecture facilitates the flow and sharing of detailed information across different layers.

Stage 15 (Intermediate Stage) At Stage 15, the resolution of the feature maps is significantly reduced, and more detailed information becomes abstracted as the features transition to higher-level semantic representations. The feature maps at this stage demonstrate the model’s global perception capability for defect regions, beginning to construct more abstract feature representations, such as high-level modeling of defect shapes, distributions, and texture patterns. This abstraction of features indicates that the BiSDE architecture is capable of not only capturing local information but also integrating the global characteristics of defects.

Stage 25 (Deep Stage) By Stage 25, the feature maps have become highly abstracted, with the resolution further reduced, showcasing the model’s ability to integrate global semantic features. At this stage, the BiSDE architecture focuses more on extracting the overall patterns and high-level features of defects rather than on capturing individual details. The model effectively balances global and local information through a multi-scale feature fusion mechanism, ensuring robust detection of complex casting defects.

Through the analysis of feature maps across the four stages, Fig. 11 intuitively illustrates the BiSDE architecture’s multi-level balancing capability in feature extraction. The early stages prioritize capturing high-resolution details, demonstrating sensitivity to small targets, while the middle and later stages abstract and integrate features to form a comprehensive understanding of the defects. This multi-level feature extraction mechanism significantly enhances the model’s robustness and generalization in casting defect detection, further validating the effectiveness of the BiSDE architecture in this task.

To further enhance the interpretability of the model, this study presents attention heatmap visualizations to demonstrate the model’s performance in detecting internal casting defects from X-ray images, with a particular focus on small defect regions, as shown in Fig. 12.

In Fig. 12, the first column represents the ground truth of defect regions, serving as a reference. In the shallow attention heatmaps, it can be observed that the attention distribution covers a broader area, including contextual information around the target regions. However, this also introduces background interference. In contrast, the deep attention heatmaps demonstrate a more focused attention distribution, with less emphasis on background features, clearly concentrating on the vicinity of the small casting defects.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we proposed an innovative approach that combines a Wasserstein distance-based loss function (NWDLOSS) with a multi-scale feature extraction architecture (BISDE) to address the challenges of small-scale defect detection in X-ray images. The BISDE architecture employs a dual encoder-decoder structure, with a novel bidirectional skip connection in the encoder to enhance feature fusion. In the decoder, the fusion of feature maps is optimized using the Hadamard product, allowing for better reconstruction of target details and spatial information. Through comparative and ablation experiments, our model demonstrated superior performance in detecting small-scale casting defects, significantly outperforming existing methods. Specifically, in the ablation study, our model achieved more than a 1.05% increase in mAP, and in comparative experiments, it achieved over a 5.36% increase in mAP.

This exceptional performance can be attributed to several key factors. First, the NWDLOSS function provides a more accurate measurement of the difference between predicted results and the true distribution, particularly excelling in detecting complex and hard-to-distinguish small-scale defects. Second, the bidirectional skip connections in the BISDE architecture’s encoder enhance feature fusion, significantly improving the model’s ability to capture multi-scale features. Additionally, the optimized feature map fusion process better reconstructs target details and spatial information, leading to a substantial increase in detection accuracy. Finally, we employed efficient data preprocessing techniques to ensure the model’s reliability and practicality in real-world applications.

Despite the significant achievements of this study, some limitations remain. First, the homogeneity and limited number of data samples are a concern. Future research could involve collaboration with other industrial teams to conduct multi-center data studies, thereby increasing the diversity and quantity of data sources and enhancing the model’s accuracy and sensitivity. Second, additional casting defect detection metrics, such as defect type, location distribution, and material properties, could be integrated to further refine the detection system and allow for more detailed defect classification based on varying standards. Moreover, while the current model focuses primarily on small-scale defect detection, future research could address defects of different sizes and types to enhance the model’s applicability and detection precision. Finally, given the limited interpretability of deep learning in industrial applications, further model optimization and the exploration of more transparent interpretation methods are necessary to develop a system that can be widely applied in industrial production.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with the industrial partners involved in this project. However, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Parlak, I. E. & Emel, E. Deep learning-based detection of aluminum casting defects and their types. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 118, 105636 (2023).

Bharambe, C., Jaybhaye, M. D., Dalmiya, A., Daund, C. & Shinde, D. Analyzing casting defects in high-pressure die casting industrial case study. Mater. Today 72, 1079–1083 (2023).

Lin, J., Yao, Y., Ma, L. & Wang, Y. Detection of a casting defect tracked by deep convolution neural network. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 97, 573–581 (2018).

Jiang, L., Wang, Y., Tang, Z., Miao, Y. & Chen, S. Casting defect detection in X-ray images using convolutional neural networks and attention-guided data augmentation. Measurement 170, 108736 (2021).

Rotella, A., Nadot, Y., Piellard, M., Augustin, R. & Fleuriot, M. Influence of defect morphology and position on the fatigue limit of cast Al alloy: 3D characterization by X-ray microtomography of natural and artificial defects. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 785, 139347 (2020).

Mery, D. & Filbert, D. Automated flaw detection in aluminum castings based on the tracking of potential defects in a radioscopic image sequence. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 18, 890–901 (2002).

Li, X. L., Tso, S. K., Guan, X. P. & Huang, Q. Improving automatic detection of defects in castings by applying wavelet technique. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53, 1927–1934 (2006).

Wu, B. et al. An ameliorated deep dense convolutional neural network for accurate recognition of casting defects in X-ray images. Knowl.-Based Syst. 226, 107096 (2021).

Xue, L. et al. A high efficiency deep learning method for the x-ray image defect detection of casting parts. Meas. Sci. Technol. 33(9), 095015 (2022).

Mery, D. Aluminum casting inspection using deep learning: A method based on convolutional neural networks. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 39(1), 12 (2020).

Kumaresan, S., Aultrin, K. J., Kumar, S. S. & Anand, M. D. Deep learning-based weld defect classification using VGG16 transfer learning adaptive fine-tuning. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 17(6), 2999–3010 (2023).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 779–788 (2016).

Da Wu, J. & Huang, Y. H. Enhanced identification of internal casting defects in vehicle wheels using YOLO object detection and x-ray inspection. Traitement Signal 40(5), 1909–1920 (2023).

Dong, C. & Duoqian, M. Control distance IoU and control distance IoU loss for better bounding box regression. Pattern Recogn. 137, 109256 (2023).

Gao, R. & Kleywegt, A. Distributionally robust stochastic optimization with Wasserstein distance. Math. Oper. Res. 48(2), 603–655 (2023).

Tan, M., Pang, R., & Le, Q. V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 10781–10790 (2020).

Mery, D., Jaeger, T. A. & Filbert, D. A review of methods for automated recognition of casting defects. Insight 44, 428–436 (2002).

Klatte, R. Computer-assisted X-ray testing for objective quality assurance of workpieces. PhD thesis, Institut für Allgemeine Elektrotechnik, Technische Universität Berlin (1985).

Heinrich, W. Ein zeitoptimaler Rangordnungsoperator für die Automatisierung der radiologischen Gußteilprüfung. Technischer Bericht 123, Institut für Allgemeine Elektrotechnik, Technische Universität Berlin (1987).

Heinrich, W. Automatic X-ray Series Testing of Cast Parts. PhD thesis, Institut für Allgemeine Elektrotechnik, Technische Universität Berlin (1988).

Santos, I., Nieves, J., Bringas, P. & Penya, Y. Machine-learning-based defect prediction in highprecision foundry production. Structural Steel and Castings: Shapes and Standards, Properties and Applications 259–276 (2010).

Wu, B., Zhou, J., Ji, X., Yin, Y. & Shen, X. Research on approaches for computer aided detection of casting defects in X-ray images with feature engineering and machine learning. Procedia Manuf. 37, 394–401 (2019).

Pastor-López, I. et al. Machine-learning-based surface defect detection and categorisation in high-precision foundry. In 2012 7th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA) 1359–1364 (2012).

Zhao, F., Mendonça, P. R. S., Yu, J. & Kaucic, R. Learning-based automatic defect recognition with computed tomographic imaging. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Melbourne, VIC, Australia 2762–2766 (2013).

Nicoletto, G., Konečná, R. & Fintova, S. Characterization of microshrinkage casting defects of Al–Si alloys by X-ray computed tomography and metallography. Int. J. Fatigue 41, 39–46 (2012).

Mery, D., Jaeger, T. & Filbert, D. A review of methods for automated recognition of casting defects. Insight 44(7), 428–436 (2002).

Cho, I. S., Hwang, J. H., Yang, J. S., Yoo, S. M. & Lim, C. H. Evaluation of defects in aluminum piston castings by using ultrasonics and computer tomography. China Foundry 9(3) (2012).

Nourian-Avval, A. & Fatemi, A. Characterization and analysis of porosities in high pressure die cast aluminum by using metallography, x-ray radiography, and micro-computed tomography. Materials 13(14), 3068 (2020).

Tenkamp, J. et al. Defect-correlated fatigue assessment of A356–T6 aluminum cast alloy using computed tomography based Kitagawa-Takahashi diagrams. Int. J. Fatigue 108, 25–34 (2018).

Fieres, J., Schumann, P. & Reinhart, C. Predicting failure in additively manufactured parts using X-ray computed tomography and simulation. Procedia Eng. 213, 69–78 (2018).

Fu, Y., Li, M. & Huang, J. Modified DeepLabV3+ algorithm for casting defect detection. In Third International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Signal Image Processing (AASIP) 12799, 231–245 (2023).

Pu, Q. C. et al. Casting-DETR: An end-to-end network for casting surface defect detection. Int. J. Metalcasting 18, 1–14 (2024).

Zhong, H. et al. STFE-Net: A multi-stage approach to enhance statistical texture feature for defect detection on metal surfaces. Adv. Eng. Inform. 61, 102437 (2024).

Zhong, H. et al. LiFSO-Net: A lightweight feature screening optimization network for complex-scale flat metal defect detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 304, 112520 (2024).

Xiao, L., Wu, B. & Hu, Y. Missing small fastener detection using deep learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–9 (2020).

Xu, J., Hu, X., Zhang, Y. & Li, Z. BHE-YOLO: Effective small target detector for aluminum surface defect detection. Adv. Theory Simul. 7, 2300563 (2024).

Zhang, R. & Wen, C. SOD-YOLO: a small target defect detection algorithm for wind turbine blades based on improved YOLOv5. Adv. Theory Simul. 5(7), 2100631 (2022).

Tellez, D. et al. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101544 (2019).

Zhang, L., Deng, Z., Kawaguchi, K., Ghorbani, A. & Zou, J. How does mixup help with robustness and generalization? Arxiv preprint. arxiv:2010.04819 (2020).

Hao, W. & Zhili, S. Improved mosaic: Algorithms for more complex images. J. Phys. 1684(1), 012094 (2020).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 7464–7475 (2023).

Kwak, S. G. & Kim, J. H. Central limit theorem: The cornerstone of modern statistics. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 70(2), 144–156 (2017).

Wang, J., Xu, C., Yang, W. & Yu, L. A normalized Gaussian Wasserstein distance for tiny object detection. arxiv preprint. arxiv:2110.13389 (2021).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 2117–2125 (2017).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 8759–8768 (2018).

Ghiasi, G., Lin, T. Y. & Le, Q. V. Nas-fpn: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 7036–7045 (2019).

Chen, J. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR) 12021–12031 (2023).

Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 213–229 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. and S.Z. wrote the main manuscript text and P.R. and T.P. prepared Figs. 1–10, X.M. prepared Table1-3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Li, H., Ren, P. et al. A detection method for small casting defects based on bidirectional feature extraction. Sci Rep 15, 6362 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90185-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90185-y

This article is cited by

-

Model of defect identification and cause tracing in casting process based on transformer structure

Production Engineering (2026)