Abstract

The production efficiency of rotifers, representing a crucial feed for fish larvae, is a key factor determining fish production in aquaculture. Poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) (PBSA) is a biodegradable polymer that enhances rotifer growth, but its effect on bacterial composition remains unknown. This study was aimed to investigate changes in the structure and function of actively growing bacterial communities in rotifer culture water after PBSA treatment. PBSA induced rapid changes in water quality, including elevated organic carbon levels, decreased pH, and increased in bacterial abundance and respiration, suggesting the elution of oligomers and monomers. Consequently, these conditions led to the increased prevalence of certain actively growing bacterial families, notably Alteromonadaceae and Hyphomonadaceae, compared with that in water without PBSA, which persisted throughout the experiment. Moreover, a decrease in ammonium concentrations was observed after PBSA treatment. As functions predicted using PICRUSt2 indicated that bacteria influenced by PBSA were unlikely to directly contribute to nitrogen conversion processes such as nitrification, denitrification, and nitrogen fixation, this observation was attributed to enhanced bacterial assimilation. These findings help elucidate how PBSA enhances rotifer production, highlighting the importance of considering the functional roles of the potential microbial consortium created by PBSA to optimize its use in seed production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rotifer Brachionus plicatilis species complex is widely used as a crucial initial feed for fish larvae during seed production1. Accordingly, the efficiency of rotifer production is a key factor determining fish production2,3. However, issues often arise during rotifer production and preservation, including a decrease in the number of rotifers due to increased free ammonia levels4 and contamination with Euplotes ciliates5, or Vibrio bacteria6. Ammonia toxicity, which can negatively affect rotifer production, is a notable concern, especially when the pH exceeds 8.5. To address the issue of ammonia toxicity, hydrochloric acid is added during production to maintain a pH near 7.07. Nevertheless, microbial contamination remains a considerable challenge, with no fundamental solution yet identified, although physical removal using filters has been implemented8. While specific solutions to these issues may vary depending on the circumstances, the most commonly employed approach is frequent water exchange to maintain the water quality of rotifer cultures. However, given that this maintenance is labor-intensive and costly, it is crucial to establish other effective approaches and technologies for seed production.

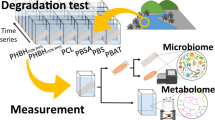

Biodegradable polymers have garnered attention due to their potential for microbial control in aquaculture. The striking efficacy of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) for controlling Vibrio campbellii, a known pathogen of Artemia brine shrimp (another crucial feed for fish larvae), has been reported9,10. Butyric acid eluted from PHB is responsible for disrupting the homeostasis of V. campbellii cells by forcing them to expend energy to export excess protons11. This approach, which employs biodegradable polymers, also holds promise for recirculation aquaculture systems, showing effectiveness in rotifer cultures12. For instance, many biodegradable polymers such as poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV), polycaprolactone (PCL), and poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) promote biological denitrification13,14,15,16,17,18. Poly(butylene succinate adipate) (PBSA) is another biodegradable polymer that has shown promise for aquaculture. PBSA exhibits denitrification activity19 similar to that of other biodegradable polymers and harbors nitrogen-fixing bacteria that accelerate polymer degradation20. A noteworthy characteristic of PBSA in rotifer production, which has not been reported for other polymers, is its dual impact: a growth-enhancing effect on rotifers and a growth-inhibiting effect on Euplotes21, which hinders rotifer growth and reduces productivity. Although changes in the microbial communities in rotifer culture water are expected upon PBSA treatment, they remain unclear. Understanding these changes is crucial for the implementation of polymers in rotifer production.

To address this issue, we investigated changes in the community structure of bacteria of actively growing bacteria (AGB) in rotifer culture water after the addition of PBSA. This study is distinct in its emphasis on the impact of PBSA on the surrounding water, which has not been previously reported. Given that AGB could play a crucial role in rotifer culture water by contributing to the metabolism and interactions among bacteria by utilizing substances for their growth, prioritizing them over non-AGB is essential. AGB were identified using a DNA tracer approach with the thymidine analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), which enables BrdU-labeled DNA to be immunochemically separated from total DNA using anti-BrdU antibodies conjugated with magnetic beads, followed by sequencing for species identification. For AGB abundance measurements, a click chemistry technique using ethynyldeoxyuridine (EdU), another thymidine analog, was applied with microscopy. Understanding the effects of PBSA on bacterial communities will provide crucial insights into the practical applications of the biodegradable polymer in aquaculture.

Results

PBSA influenced rotifer culture water quality throughout the experiment

We conducted a 12-day-incubation experiment using rotifer culture water. Two tanks were prepared for each experimental group: one group with the addition of PBSA (PBSA group) and another group as the control (Ctrl group), resulting in a total of four tanks for the experiment.

Throughout the experiment, the water temperature and salinity ranged from 19.52 to 31.14 °C and 3.10 to 3.20%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). These values were within the typical range for rotifer cultures during seedling production. In the PBSA group, the pH decreased from 8.16 (Tank 1) and 8.26 (Tank 2) on day 0 to 7.28 (Tank 1) and 7.27 (Tank 2) on day 7 (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the pH in the Ctrl group remained relatively stable at 7.97 ± 0.12 throughout the experiment. The initial dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations in the PBSA group were 6.998 ± 0.066 and 6.970 ± 0.029 mg/L in Tanks 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 1b). These reached minimum values of 4.039 ± 0.028 and 4.189 ± 0.032 mg/L in Tanks 1 and 2, respectively, on day 4 before subsequently increasing. The DO concentration in the Ctrl group (6.472 ± 0.226 mg/L, coefficient of variance (CV): 3.5%) was more stable than that in the PBSA group (5.606 ± 0.793 mg/L, CV: 14.1%). The total organic carbon (TOC) concentrations in the PBSA group were consistently higher than those in the Ctrl group throughout the experiment (Fig. 1c). The dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations in the PBSA group showed a rapid increase after the start of the experiments, reaching a maximum value (11.84 and 12.03 mg C/L in Tanks 1 and 2, respectively) on day 2 and, maintaining higher levels compared to those in the Ctrl group (1.74 ± 0.25 mg C/L) (Fig. 1d). The NH4-N concentrations in the Ctrl group remained stable throughout the experiment, except in Tank 4 on day 5 (Fig. 1e). In contrast, NH4-N concentrations in the PBSA group fell below the detection limit (0.5 mg/L) after day 3. No other nutrients (NO2-N, NO3-N, or PO4-P) were detected. The weight loss of PBSA after the experiment was 0.6689 g (loss ratio of 0.67%) in Tank 1 and 0.7406 g (loss ratio of 0.74%) in Tank 2 (Supplementary Table S1).

PBSA influenced bacterial abundance and respiration

The abundance of culturable bacteria on 1/2 ZoBell agar in the PBSA group surpassed that in the Ctrl group. However, the highest abundances in both groups were recorded on day 3: (2.02 ± 0.62) × 106 and (2.25 ± 0.50) × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL for Tanks 1 and 2, respectively, in the PBSA group, and (7.00 ± 3.58) × 105 and (6.83 ± 1.47) × 105 CFU/mL for Tanks 3 and 4, respectively, in the Ctrl group (Fig. 2a). In the PBSA group, the abundance of culturable bacteria increased again in the later phase of the experiment. Regarding the abundance of Vibrio bacteria on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salt-sucrose (TCBS) agar, a rapid initial increase in abundance was observed in the PBSA group, especially from days 1 to 3, compared with that in the Ctrl group (Fig. 2b). However, the abundance steadily declined thereafter, reaching undetectable levels (below the detection limit of 33 CFU/mL) by day 7. Total bacterial abundance, determined via a direct count, exhibited patterns similar to those in culturable bacteria, with the highest abundances recorded on day 3: (1.10 ± 0.20) × 107 and (9.65 ± 2.29) × 106 CFU/mL for Tanks 1 and 2, respectively, in the PBSA group (Fig. 2c). In contrast, abundances in the Ctrl group averaged (1.15 ± 0.72) × 106 CFU/mL and remained relatively stable throughout the experiment.

Bacterial parameters, including (a) ZoBell colony number, (b) TCBS colony number, (c) total bacterial abundance, (d) proportion of EdU-labeled cells to total bacterial abundance, (e) bacterial respiration rate, and (f) cell-specific bacterial respiration rate throughout the experiment. n.d.: no data.

The proportion of EdU-labeled bacteria among total bacteria in the PBSA group was also higher than that in the Ctrl group (Fig. 2d). While the percentages varied throughout the experiment in both groups, they averaged 20% (CV: 48%) in the PBSA group and 13% (CV: 45%) in the Ctrl group. The bacterial respiration rate in the PBSA group showed the highest values on day 3, at 2.460 ± 0.043 mg O2/L/d in Tank 1 and 2.528 ± 0.163 mg O2/L/d in Tank 2, surpassing that in the Ctrl group where the highest values were recorded on day 2: 0.577 ± 0.137 mg O2/L/d in Tank 3 and 1.175 ± 0.164 mg O2/L/d in Tank 2 (Fig. 2e). The variation in cell-specific bacterial respiration in the PBSA group, ranging from 0.03 to 0.53 pg O2/cell/d (Fig. 2f), appeared to be related to the changes in ZoBell colony number and bacterial abundance. In contrast, cell-specific bacterial respiration in the Ctrl group appeared to increase during the late phase of the experiment.

PBSA modified bacterial community structures and functions

The number of non-chimeric reads ranged from 27,119 to 49,348 (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Table S2). The alpha diversity indices, including observed amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (pd), Shannon entropy, and Pielou’s evenness, were within the ranges of 52–249, 6.29–21.88, 3.80–5.77, and 0.57–0.79, respectively (Table S3). All indices of BrdU-incorporated communities in the PBSA group, except Pielou’s evenness, were significantly lower than those of the total communities (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p < 0.05). Not all the observed ASVs in the total communities were detected in BrdU-incorporated communities (Supplementary Fig. S3). The observed ASV and Faith pd indices in the PBSA group from days 4 to 12 were significantly lower than those in the Ctrl group (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p < 0.05), whereas the Shannon entropy and Pielou’s evenness indices were not significantly different between these groups (Fig. 3).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed distinct differences in bacterial community structures throughout the experiment (Fig. 4). Similar to the alpha diversity indices (Fig. 3), the structures of the total and BrdU-incorporated communities were significantly different in both the PBSA and Ctrl groups (PERMANOVA, p = 0.0001). Furthermore, the community structures in the PBSA group exhibited a notable distinction from those in the Ctrl group, undergoing significant changes between days 0 and 4.

The community structures of the bacterial taxa are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, illustrating their relative abundance at the phylum level. We identified 24 phyla, among which Proteobacteria (26.3–87.2%; mean, 57.9%) and Bacteroidota (11.5–62.1%; mean, 28.5%) were predominant. Archaea constituted a negligible proportion (< 0.2%) and was observed only on the first day of the experiment (day 0). The differences in community structures between the total and BrdU-incorporated bacteria were aligned with the PCoA results (Fig. 4). In the BrdU-incorporated communities (days 4, 8, and 12), three dominant bacterial classes were observed: Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria (phylum Proteobacteria), and Bacteroidia (phylum Bacteroidota) (Fig. 5a). Bacteroidia exhibited a greater abundance in the Ctrl group (mean, 46.7%) than in the PBSA group (mean, 17.5%) (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p = 0.003948). Conversely, Alphaproteobacteria was more dominant in the PBSA group (mean, 69.7%) than in the Ctrl group (mean, 30.3%) (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p = 0.003948), whereas no significant difference was observed for Gammaproteobacteria (mean, 9.1% and 16.9% in the PBSA and Ctrl groups, respectively; Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p = 0.2623). At the family level, the dominant bacterial families were consistent with the phylum and class levels: Flavobacteriaceae (class Bacteroidia; mean, 21.2%) and Rhodobacteraceae (class Alphaproteobacteria; mean, 28.2%) (Fig. 5b; Table S4). Flavobacteriaceae was significantly more abundant in the Ctrl group (mean, 34.2%) than in the PBSA group (mean, 8.2%) (Welch’s t-test, p = 0.00840), but no significant difference was observed for Rhodobacteraceae (mean, 31.0% and 25.5% in the PBSA and Ctrl groups, respectively; Welch’s t-test, p = 0.441) (Fig. 6a). Among the families that were more abundant in the PBSA group, Hyphomonadaceae (class Alphaproteobacteria) was predominant (mean, 32.2%) and showed a significant increase in abundance throughout the experiment; this family was nearly absent in the Ctrl group (mean, 1.2%). Representing bacterial taxa potentially harboring fish pathogens, the family Vibrionaceae was initially present in both the PBSA and Ctrl groups, constituting 5.33–8.25% of the BrdU-incorporated bacteria (Table S5). However, in the PBSA group, Vibrionaceae became nearly undetectable among BrdU-incorporated bacteria by day 4 (0.03% for Tank 1, absent for Tank 2), whereas in the Ctrl group, it was still detectable until day 8 (0.07 and 0.23% for Tanks 3 and 4, respectively).

Bacterial taxa of the BrdU-labeled communities at the family level throughout the experiment days (days 4, 8, and 12). (a) Relative abundance of the top ten bacterial taxa in the BrdU-labeled communities at the family level in the PBSA and Ctrl groups. p-values show the results of Welch’s t-test. (b) ASVs of BrdU-labeled communities at the family level in the PBSA and Ctrl groups. ASVs with |log2FoldChange| > 1 and adjusted P < 0.01 according to the DESeq2 analysis are shown. Positive and negative values for the log2FoldChange indicate significantly abundant ASVs in the PBSA and Ctrl groups, respectively. The bacterial families shown in red indicate the top ten bacterial taxa at the family level.

According to the DESeq2 analysis results, clear differences in ASV abundance between the PBSA and Ctrl groups were observed, varying throughout the experimental period (days 4, 8, and 12), as shown in Fig. 6b. ASVs belonging to the top ten bacterial family taxa were also detected in the PBSA group on days 4, 8, and 12, with 22 ASVs (12 families), 19 ASVs (10 families), and 17 ASVs (6 families), respectively. Among these, Alteromonadaceae (class Gammaproteobacteria) and Hyphomonadaceae were identified as characteristic ASVs in the PBSA group, consistent with the abundance of the top ten families. However, some ASVs related to Rhodobacteraceae (class Alphaproteobacteria), for which no significant difference in abundance was observed between the PBSA and Ctrl groups (Fig. 6a), were also identified as characteristic ASVs in the PBSA group.

The number of observed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) orthologs and enzymes ranged from 3,781 to 4,810, and from 1,450 to 1,686, respectively (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). Alpha diversity indices such as Shannon entropy and Pielou’s evenness were within the ranges of 10.78–11.09 and 0.90–0.93, respectively, for KEGG orthologs, and of 9.52–9.68 and 0.89–0.92, respectively, for enzymes (Supplementary Table S8). In the PBSA group, only the number of observed KEGG orthologs significantly differed between the total and BrdU-incorporated communities (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p = 0.003948). In the BrdU-incorporated communities, the numbers of observed KEGG orthologs and enzymes in the PBSA group from days 4 to 12 were significantly lower than those in the Ctrl group (Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, p < 0.05). In contrast, the Shannon entropy and Pielou’s evenness indices were not significantly different between these groups (Supplementary Fig. S5). The predicted functions varied between the experimental groups and throughout the experiment, although regular patterns similar to those for the community structures were not observed (Supplementary Fig. S6). However, predicted functions that were significantly abundant in both the PBSA and Ctrl groups were detected (Table S9). In the PBSA group, 216 out of 5,033 KEGG orthologs represented unique functions exclusively detected in this group, while a further 809 KEGG orthologs exhibited consistently higher enrichment in the PBSA group than in the Ctrl group throughout the experiment. Additionally, 74 out of 1,790 enzymes were unique to the PBSA group, with an additional 249 enzymes showing a higher enrichment than in the Ctrl group. KEGG orthologs associated with nitrate and/or nitrite reduction (K00368, nirK; K02567, napA; and K02568, napB) were identified in both the Ctrl and PBSA groups. Nitrogen fixation processes were observed in the Ctrl group, as indicated by the results of both KEGG ortholog (e.g., K02586, nifD; K02588, nifH; K02591, nifK) and enzyme (EC 1.18.6.1, nitrogenase) analyses. The KEGG ortholog associated with ammonia oxidation (K10944, amoA) was identified on the first day of the experiment (day 0), but no nitrification processes were observed in either the Ctrl or PBSA groups during incubation. Among the remaining KEGG orthologs and enzymes, DESeq2 analysis revealed several to be significantly more enriched in the PBSA group than in the Ctrl group (Supplementary Fig. S7). However, no clearly distinctive or characteristic features could be identified.

Discussion

Impact of PBSA on bacterial community structure and rotifer culture water quality

The results of this study highlighted significant alterations in the community structure of AGB in rotifer culture waters after the addition of PBSA (Figs. 4 and 5), with a limited number of bacterial taxa compared with that in the Ctrl group (Fig. 3). Various biodegradable polymers have been suggested to induce different changes in microbial communities. For example, Omura et al.22 showed that both seawater and sediment microbial communities show distinct responsed to polymers, such as PCL and PBSA. However, previous studies focused on the microbial composition within the polymer itself, such as on the surfaces and biofilms of the plastisphere. Although several studies have reported the influence of PBSA on soil microbial environments23,24,25, its impact on aquatic environments remains largely unexplored. Furthermore, as the potential of polymers such as PBSA for microbial control in aquaculture has received limited attention, the present study contributes important insights to the field.

In this study, PBSA treatment promptly induced changes in rotifer culture water quality, with notable increases and decreases in TOC concentration and pH, respectively, observed at the outset of the experiment (Fig. 1). These changes strongly imply the elution of oligomers and monomers from PBSA, which was supported by the observed decrease in the weight of PBSA (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, the TOC decreased immediately, accompanied by marked increases in DOC concentration, bacterial abundance, and respiration (Figs. 1 and 2). This suggests that PBSA-derived organic matter can be utilized as a favorable substrate for bacterial growth and respiration. Previous studies have suggested that biodegradable polymers can be carbon sources for bacterial growth13,14. Our results study also suggest that these environmental modifications induced by PBSA influenced bacterial activity. These findings contribute to our understanding of how PBSA, as a microbial control agent, not only impacts bacterial communities but also dynamically alters the chemical composition of the water, fostering conditions conducive to bacterial growth.

PBSA as a microbial control agent

In the present study, the activity of Vibrio bacteria decreased immediately after the addition of PBSA (Supplementary Table S5), and no other pathogenic bacteria known to affect fish or rotifers were detected, suggesting that PBSA could be a valuable microbial control agent for rotifer production. This crucial confirmation of pathogens is among the most important evidence supporting the application of PBSA in actual seed production. Although PBSA itself did not exhibit direct inhibitory effects on Vibrio bacteria21, the suppression of DNA-synthesizing activity (BrdU-incorporating activity) occurred earlier in the PBSA group than in the Ctrl group (Supplementary Table S5). One possible explanation for this is the indirect effect of other bacteria influenced by PBSA on Vibrio species. Previous reports on fish-rearing water have demonstrated the role of photosynthetic metabolites from microalgae, such as Nannochloropsis oculate and Chlorella vulgaris, in enhancing the capabilities of Rhodobacteraceae (class Alphaproteobacteria). These enhanced Rhodobacteraceae, in turn, inhibit the growth of Vibrio bacteria26,27,28,29. This strategic management of rearing water, commonly referred to as “green water30, ” has emerged as a promising technique in seed production involving rotifer culture. The fundamental principle behind “green water” lies in the successful application of substances that promote beneficial bacteria while controlling harmful bacteria. Notably, PBSA and its eluates also harbored several Rhodobacteraceae members (Fig. 6b), potentially suggesting similar interactions among bacteria, to those observed in the case of microalgae. This “green water”-like technique using PBSA is paramount for sustaining desirable bacterial communities for rotifer and fish larva production31. Future studies should focus on analyzing not only the direct effects of PBSA and its degradation products on Vibrio strains but also the interactions between Vibrio species and the Rhodobacteraceae members stimulated by PBSA in this study. Such research would be beneficial for elucidating the potential mechanisms underlying the observed effects and supporting the application of PBSA as a microbial control agent.

PBSA had a profound impact on the bacterial community structures in rotifer culture water, leading to a pronounced predominance of Hyphomonadaceae (class Alphaproteobacteria) bacteria throughout the experiment. Members of Hyphomonadaceae are known for their role in organic matter degradation and biofilm formation, particularly in marine environments. Certain strains also exhibit nitrate reduction activity32, suggesting their potential contribution to controlling the nitrogen levels in rotifer culture water. Furthermore, this bacterial group appears to be a common degrader of biodegradable polymers in ocean environments, particularly in surface seawater22. Although some of the degraders in this study were consistent with those reported previously, the major groups differed, even among similar marine environments. The bacterial groups stimulated by PBSA in this study were also distinct from those typically dominating soil environments23,25. This distinction is likely attributable not only to environmental differences but also to the bacterial community structure. Rotifers in seed production were cultured using an established protocol, such that the associated bacterial communities were in a stable condition. Accordingly, Hyphomonadaceae emerged as an abundant and potential key species among the bacteria influenced by PBSA, contributing to both the “green water”-like function and nitrogen cycles in rotifer culture water. Alteromonadaceae, another predominant group, has also been identified as a degrader of biodegradable polymers33,34. However, its specific roles in polymer degradation and utilization remain unclear. Future studies, emplying isolation and metagenomic analyses, should prioritize these bacterial groups to thoroughly investigate their functions and ecological roles.

PBSA-induced ammonium assimilation

Although previous studies have suggested that bacteria influenced by PBSA may enhance nitrogen conversion processes, including denitrification and nitrogen fixation19,20,23,25, our PICRUSt2-based findings were not consistent with these studies, especially regarding ammonium concentration dynamics. Ammonium concentrations in the Ctrl group remained constant (approximately 1 mg/L) throughout the experiment, while those in the PBSA group decreased several days after the start of the experiment and then reached the detection limit (< 0.5 mg/L) (Fig. 1e). Likely explanations for the decrease include the assimilation of ammonium by heterotrophic bacteria rather than nitrification followed by denitrification. This process was potentially enhanced by carbon-rich organic compounds leaching from PBSA (Fig. 1c and d, Supplementary Table S1), which promoted bacterial growth and increased the demand for nitrogen, including ammonium, for incorporation into microbial biomass. Indeed, a remarkable increase in bacterial abundance and respiration was observed on day 3 (Fig. 1a and b, and 1e), coinciding with the decrease in ammonium concentration. Maintaining optimal nitrogen conditions is a key process for effective rotifer production, as optimized rotifer growth depends on nitrogenous factors such as ammonium4. Previous studies have reported the denitrification performance of biodegradable polymers, such as PCL16, PHBV15, PBS13, and PBSA19. Moreover, other studies have indicated that PBSA enhances nitrogen fixation in soil20,23,25. However, in the rotifer culture in this study, signs of such nitrogen conversion processes reported in earlier studies were not observed. To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying ammonium assimilation and the role of PBSA in maintaining nitrogen conditions in rotifer culture water, future studies should focus on isolating and characterizing the specific bacterial strains responsible for ammonium assimilation. Such research will contribute to a better understanding of nitrogen management in ecosystems influenced by biodegradable polymers like PBSA and will provide insights for optimizing effective nitrogen cycling conditions in various environmental and industrial contexts.

Conclusion and future directions

It has been noted that BrdU and EdU could be incorporated into bacterial cells not only during DNA synthesis associated with cell division but also during DNA repair, and that some bacteria may not incorporate BrdU and EdU due to the lack of thymidine kinase35,36. Despite these points, studies have shown that BrdU incorporation strongly correlates with the traditional thymidine method37 and that there is no bias in the phylogenetic affiliations of bacteria incorporating BrdU38. In this study, BrdU-incorporated bacteria are regarded as AGB, offering a powerful approach to specifically identify active growers, though careful interpretation may be necessary in certain cases.

Despite these methodological considerations, this study demonstrated the impact of PBSA on the microbial communities in rotifer culture water, revealing a distinctive bacterial group stimulated by the elution of PBSA monomers, oligomers, and degradation products. These conditions are favorable not only for desirable bacterial communities, but also for rotifers21, whereas harmful bacteria such as Vibrio, known represent pathogens affecting rotifers and fish, remain inactivated and/or undetected. PBSA in rotifer cultures creates diverse ecological habitats for microbes and optimal conditions for rotifer development. Moving forward, it is imperative to elucidate the detailed functions and roles of key bacteria identified in this study, such as Hyphomonadaceae and Rhodobacteraceae, in facilitating the “green water”-like effect and nitrogen cycling in rotifer culture. DESeq2 analysis of KEGG orthologs and enzymes revealed that certain bacterial functions significantly increased in response to PBSA (Supplementary Fig. S7). As PBSA is expected to influence not only nitrogen cycling but also a broad range of complex interactions, limitations remain in linking these functions to specific bacterial taxa using 16 S amplicon analysis. A combination of bacterial isolation and metagenomic analyses is therefore essential for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of these processes, particularly regarding nitrogen cycling and microbial interactions in rotifer culture water influenced by PBSA. These findings contribute to our understanding of how PBSA enhances rotifer growth while suppressing Euplotes and Vibrio proliferation. Clarifying the functions of the potential microbial consortium created by PBSA is paramount for optimizing the application of this promising material in seed production technology.

Methods

Experimental design

Rotifer culture water and UV-treated seawater were obtained from the Susami Hatchery, Aquaculture Technology and Production Center, Kindai University, Wakayama, Japan, and were used commercially for seed production. The rotifer culture water obtained was filtered through a 60 μm nylon mesh to remove rotifers, followed by serial filtration with a 20 μm nylon mesh and a 3 μm pore size polycarbonate filter to obtain free-living bacteria. The filtered rotifer water was then diluted ten-fold using UV-treated seawater and transferred to 20 L Nalgene polycarbonate tanks (Supplementary Fig. S8). Two tanks were prepared for each experimental group: one group with the addition of PBSA (PBSA group), utilizing “Bio-PBS” PBSA pellets (Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and another group as the control (Ctrl group), resulting in a total of four tanks for the experiment. The PBSA concentration was set at 5 g/L, which has been shown to significantly affect denitrification19 and rotifer growth21. Incubation was conducted for 12 days with gentle stirring at 540 rpm using a magnetic stirrer (HE-20GB, Koikeseisakusho Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan), with the cap slightly loosened to ensure oxygen supply.

Rotifer culture water quality throughout the experiment

Subsamples to measure rotifer culture water quality, including water temperature, salinity, pH, DO, TOC, DOC, total nitrogen (TN), and nutrients (NH4-N, NO3-N, NO2-N, PO4-P) were taken every day, except on day 10. We used a portable DO meter (ARO-PR; JFE Advantech Co., Ltd., Hyogo, Japan) to determine the water temperature and DO concentration. The subsamples were placed in three clean oxygen bottles for each experimental tank through gentle siphoning with a combusted Whatman GF/C filter to avoid dissolving oxygen from the air. Salinity and pH were measured using a portable salinity meter (Salt-free 2500, AS ONE Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and a portable pH meter (LAQUAtwin AS-212, HORIBA Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), respectively. For organic carbon, the TOC subsamples were collected directly into a glass ampule, whereas for DOC, they were filtered through a combusted Whatman GF/F filter before being transferred to another ampule using a syringe. TOC and DOC concentrations were analyzed using a TOC-V CPH TOC analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). For subsamples for TN and nutrient content determination, the water was collected taken into a clean-washed polycarbonate bottle and stored at − 30 °C until analysis. A TN analyzer ND-210 (Nittoseiko Analytech Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan) was used to measure TN and a high-performance ion chromatograph IC-2010 (Tosoh Techno-System, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure NO3-N, NO2-N, and PO4-P. NH3-N levels were measured using a DR3900 spectrophotometer (Hach Company, Tokyo, Japan). To estimate the elution from PBSA, we measured the weight of PBSA before and after the experiment using an electronic balance (GR-200; A&D Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After the experiment, the PBSA was soaked in a reagent for appliance cleaning, Contaminon® N (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), for 1 day. Subsequently, the samples were rinsed to remove the reagents and dried. Unused PBSA was subjected to the same washing procedure to account for any weight loss during the washing step.

Bacterial abundance and respiration

Bacterial abundance was estimated using culture techniques: 1/2 ZoBell agar for total culturable bacteria, TCBS agar for culturable Vibrio, and a direct count using fluorescence microscopy. To estimate the number of culturable bacteria present, subsamples were serially diluted 10-fold in autoclaved seawater, and 5 µL of each diluted subsample was dropped (six drops per dilution) onto each plate using the drop plate method. All colonies on the plates were counted under a stereomicroscope after incubation at approximately 26 °C for 7 days on 1/2 ZoBell agar and 24 h on TCBS agar. The results are expressed as CFU. For direct counting, the subsamples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (final concentration) and stored at 4 °C until analysis. Bacterial cells were collected onto 0.2-µm pore size polycarbonate filter under a < 100 mmHg vacuum, and the bacterial DNA was stained using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; final concentration: 1 µg/mL). More than 300 cells, or at least 10 microscopic fields per sample, were counted using an epifluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) with a U-MWU2 filter.

The abundance of DNA-synthesizing bacteria was measured using a click chemistry reaction with 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU). After subsampling, the samples were incubated with EdU (final concentration: 1 µM) for 1 h in the dark and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (final concentration). Bacterial cells were filtered through 0.2 μm pore size polycarbonate black filters coated with poly-L-lysine under a < 100 mmHg vacuum, and the filter was dried well. EdU-incorporated bacterial cells were detected using an Invitrogen™ Click-iT™ EdU kit (Invitrogen, OR, USA). The slides were examined under an epifluorescence microscope (BX51) equipped with an ORCA-R2 charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The images (stored as TIFF files) were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus version 6.3 image analysis software (Media Cybernetics, MD, USA).

Bacterial respiration was measured using the oxygen consumption method. The subsamples were placed into three clean oxygen bottles for each experimental bottle using a gentle siphon with a combusted Whatman GF/C filter to obtain only bacteria without any oxygen contamination. After measuring the DO concentration before incubation using a portable DO meter (ARO-PR, JFE Advantech Co., Ltd.), glass bottles were triple-wrapped with aluminum foil to ensure light protection and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the DO concentration was measured in the same manner as described above. The bacterial respiration rate was calculated from the oxygen consumption before and after incubation.

Bacterial community structure analysis

The community structure of AGB was analyzed using the BrdU method following a previously reported protocol39. One liter of each subsample was collected into polycarbonate bottles before the experiment and after incubation for 4, 8, and 12 days. Each subsample was incubated in the dark with BrdU (final concentration: 1 µM) as a DNA tracer for 1 h. After incubation, the bacterial cells were collected onto 0.2-µm pore size Sterivex cartridge filters and stored at − 30 °C until further analysis. Bacterial DNA was extracted using the xanthogenate SDS DNA extraction method, and BrdU-labeled DNA was immunocaptured from 1,000 ng of the extracted DNA. After confirming the success of BrdU-labeled DNA immunocapture via PCR amplification, Illumina MiSeq sequencing was performed by Bioengineering Lab. Co., Ltd. (Kanagawa, Japan), focusing on 300-bp paired-end sequences (301 cycles×2) for the V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene (515 F forward, 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′; 805R reverse, 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), targeting both bacteria and archaea40.

Sequence processing and statistical analysis

Sequencing processing was performed according to a previously reported protocol39. Sequenced reads were analyzed using the Qiime2 Core 2021.11 distribution41. Raw sequence data were demultiplexed using the q2-demux plugin, and primer sequences, low-quality sequences, and chimeric reads were removed using DADA242 by Bioengineering Lab. Co. Ltd. ASVs were taxonomically assigned using the q2-feature-classifier plugin43 of the classify-sklearn naïve Bayes taxonomy classifier against the Silva database (silva-138-99). ASVs related to eukaryotes, mitochondria, chloroplasts, cyanobacteria, and unassigned taxa were excluded from further analyses. All ASVs aligned using mafft44 via q2-alignment were used for phylogenetic tree construction using fasttree245 via q2-phylogeny. Functions based on the KEGG46 and Enzyme Commission (EC) number databases were predicted for ASVs using a phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved state (PICRUSt2) analysis47 via q2-picrust2. Alpha diversity metrics (distinct ASVs, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, Shannon entropy, and Pielou’s evenness) were computed after rarefication with the minimum sequences, abundance of ASVs, or functions predicted by PICRUSt2 using q2-diversity. A beta diversity Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index for bacterial community structures and functions was calculated with the normalized relative abundance per sample using q2-diversity, and the results were subjected to PCoA. Significant differences between the Ctrl and PBSA groups were assessed using either the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test or Welch’s t-test with a significance level of 0.05. For BrdU-incorporated communities, samples from days 4, 8, and 12 were used because there were no significant differences on day 0, the first day of the experiment, between the PBSA and Ctrl groups.

Data availability

Raw sequence data from this study have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) Sequence Read Archive under the DRA Run accession numbers DRR536053–DRR536084. The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary material. Additional information can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

20 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94329-y

References

Conceição, L. E. C., Yúfera, M., Makridis, P., Morais, S. & Dinis, M. T. Live feeds for early stages of fish rearing. Aquacult. Res. 41, 613–640 (2010).

Yoshimatsu, T. & Hossain, M. A. Recent advances in the high-density rotifer culture in Japan. Aquacult. Int. 22, 1587–1603 (2014).

Hagiwara, A., Suga, K., Akazawa, A., Kotani, T. & Sakakura, Y. Development of rotifer strains with useful traits for rearing fish larvae. Aquaculture 268, 44–52 (2007).

Yu, J. P. & Hirayama, K. Study on the unexpected sudden decrease and suppressed growth of the rotifer population in mass culture—I the effect of un-ionized ammonia on the population growth of the rotifer in mass culture. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 52, 1509–1513 (1986).

Cheng, S. H., Aoki, S., Maeda, M. & Hino, A. Competition between the rotifer Brachionus Rotundiformis and the ciliate Euplotes vannus fed on two different algae. Aquaculture 241, 331–343 (2004).

Yu, J. P., Hino, A., Noguchi, T. & Wakabayashi, H. Toxicity of Vibrio alginolyticus on the survival of the Rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 56, 1455–1460 (1990).

Yoshimura, K., Hagiwara, A., Yoshimatsu, T. & Kitajima, C. Culture technology of marine rotifers and the implications for intensive culture of marine fish in Japan. Mar. Freshw. Res. 47, 217–222 (1996).

Hagiwara, A., Gallardo, W. G., Assavaaree, M., Kotani, T. & de Araujo A. B. Live food production in Japan: Recent progress and future aspects. Aquaculture 200, 111–127 (2001).

Defoirdt, T. et al. The bacterial storage compound poly-ß-hydroxybutyrate protects Artemia franciscana from pathogenic Vibrio campbellii. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 445–452 (2007).

Halet, D. et al. Poly-ß-hydroxybutyrate-accumulating bacteria protect gnotobiotic Artemia franciscana from pathogenic Vibrio campbellii. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60, 363–369 (2007).

Defoirdt, T., Boon, N., Sorgeloos, P., Verstraete, W. & Bossier, P. Short-chain fatty acids and poly-β-hydroxyalkanoates: (New) Biocontrol agents for a sustainable animal production. Biotechnol. Adv. 27, 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.026 (2009).

Suantika, G., Dhert, P., Nurhudah, M. & Sorgeloos, P. High-density production of the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis in a recirculation system: consideration of water quality, zootechnical and nutritional aspects. Aquacult. Eng. 21, 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8609(99)00031-X (2000).

Zhu, S. M. et al. Biological denitrification using poly(butylene succinate) as carbon source and biofilm carrier for recirculating aquaculture system effluent treatment. Bioresour Technol. 192, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.06.021 (2015).

Luo, G., Hou, Z., Tian, L. & Tan, H. Comparison of nitrate-removal efficiency and bacterial properties using PCL and PHBV polymers as a carbon source to treat aquaculture water. Aquacult. Fish. 5, 92–98 (2020).

Xu, Z., Song, L., Dai, X. & Chai, X. PHBV Polymer supported denitrification system efficiently treated high nitrate concentration wastewater: Denitrification performance, microbial community structure evolution and key denitrifying bacteria. Chemosphere 197, 96–104 (2018).

Chu, L. & Wang, J. Denitrification performance and biofilm characteristics using biodegradable polymers PCL as carriers and carbon source. Chemosphere 91, 1310–1316 (2013).

Liu, D. et al. Poly(butylene succinate)/bamboo powder blends as solid-phase carbon source and biofilm carrier for denitrifying biofilters treating wastewater from recirculating aquaculture system. Sci. Rep. 8, 3289 (2018).

Deng, Y. L. et al. The impact of DO and salinity on microbial community in poly(butylene succinate) denitrification reactors for recirculating aquaculture system wastewater treatment. AMB Express. 7, 113 (2017).

Yamada, T. et al. 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of microbiota in polybutylene succinate adipate-packed denitrification reactors used for water treatment of land-based recirculating aquaculture systems. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 8, e01295–e01219 (2019).

Tanunchai, B. et al. Nitrogen fixing bacteria facilitate microbial biodegradation of a bio-based and biodegradable plastic in soils under ambient and future climatic conditions. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts. 24, 233–241 (2022).

Taniguchi, A. et al. Addition of the biodegradable polymer poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) improves rotifer growth and prevents contamination. Aquacult. Sci. 71, 75–85 (2023).

Omura, T. et al. Microbial decomposition of biodegradable plastics on the deep-sea floor. Nat. Commun. 15, 568 (2024).

Purahong, W. et al. Back to the future: Decomposability of a biobased and biodegradable plastic in field soil environments and its microbiome under ambient and future climates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12337–12351 (2021).

Tanunchai, B. et al. Analysis of microbial populations in plastic–soil systems after exposure to high poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) load using high-resolution molecular technique. Environ. Sci. Eur. 33, 105 (2021).

Tanunchai, B. et al. Fate of a biodegradable plastic in forest soil: Dominant tree species and forest types drive changes in microbial community assembly, influence the composition of plastisphere, and affect poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 873, 162230 (2023).

Sharifah, E. N. & Eguchi, M. The phytoplankton Nannochloropsis oculata enhances the ability of Roseobacter clade bacteria to inhibit the growth of fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. PLoS ONE. 6, e26756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026756 (2011).

Sharifah, E. N. & Eguchi, M. Mixed cultures of the phytoplankton Nannochloropsis oculata and the marine bacterium Sulfitobacter sp. RO3 inhibit the growth of virulent strains of the major fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Aquacult. Sci. 60, 39–45 (2012).

Sharifah, E. N. & Eguchi, M. Benefits of live phytoplankton, Chlorella vulgaris, as a biocontrol agent against fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Fish. Sci. 78, 367–373 (2012).

Taniguchi, A., Sharifah, N. E. & Eguchi, M. Possible role of microalga Nannochloropsis in controlling Vibrio species in fish larva rearing water. Aquacult. Sci. 59, 451–458 (2011).

Palmer, P. J., Burke, M. J., Palmer, C. J. & Burke, J. B. Developments in controlled green-water larval culture technologies for estuarine fishes in Queensland, Australia and elsewhere. Aquaculture 272, 1–21 (2007).

Taniguchi, A., Aoki, R., Inoue, I. & Eguchi, M. Succession of the intestinal bacterial community in Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) larvae. PLoS ONE. 17, e0275211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275211 (2022).

Fukui, Y. et al. Algimonas porphyrae gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Hyphomonadaceae, isolated from the red alga Porphyra yezoensis. Int. J. Syst. Evol.Microbiol. 63, 314–320 (2013).

Morohoshi, T., Ogata, K., Okura, T. & Sato, S. Molecular characterization of the bacterial community in biofilms for degradation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) films in seawater. Microbes Environ. 33, 19–25 (2018).

Yokoyama, D., Takamura, A., Tsuboi, Y. & Kikuchi, J. Large-scale omics dataset of polymer degradation provides robust interpretation for microbial niche and succession on different plastisphere. ISME Commun. 3, 67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43705-023-00275-z (2023).

Urbach, E., Vergin, K. L. & Giovannoni, S. J. Immunochemical Detection and isolation of DNA from metabolically active Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1207–1213 (1999).

Hamasaki, K., Long, R. A. & Azam, F. Individual cell growth rates of marine bacteria, measured by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 35, 217–227 (2004).

Steward, G. F. & Azam, F. Bromodeoxyuridine as an alternative to 3H-thymidine for measuring bacterial productivity in aquatic samples. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 19, 57–66 (1999).

Mou, X., Sun, S., Edwards, R. A., Hodson, R. E. & Moran, M. A. Bacterial carbon processing by generalist species in the coastal ocean. Nature 451, 708–711 (2008).

Taniguchi, A., Kuroyanagi, Y., Aoki, R. & Eguchi, M. Community structure and predicted functions of actively growing bacteria responsive to released coral mucus in surrounding seawater. Microbes Environ. 38, ME23024. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME23024 (2023).

Caporaso, J. et al. (ed, G.) Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108 Supplement 1, 4516–4522 (2011).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z (2018).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., Miyata, T. & & MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 15, 3059–3066 (2002).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 5, e9490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 (2010).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 685–688 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hirokazu Shiba, Isamu Inoue, and the staff at Susami Hatchery, Kindai University, for providing rotifer culture water and Manato Hatashita and Takahisa Nishijima for their help with the PBSA experiment. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing. This work was supported by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) and Agricultural Technology and Innovation Research Institute, Kindai Univ. (Nara, Japan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ak.T.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. S.S.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. T.K. and Ay.T.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review and editing. M.E.: Supervision, Writing –review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Tomoki Kawagishi and Ayumi Tanaka are employed by the Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation. However, this affiliation does not alter the author’s adherence to all journal policies on sharing data and materials. All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incomplete. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction published with this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taniguchi, A., Shirakashi, S., Kawagishi, T. et al. The biodegradable polymer poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) modulates the community structures of actively growing bacteria in rotifer culture water. Sci Rep 15, 5572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90282-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90282-y