Abstract

To address the challenges of motor system temperature rising and the failure of temperature-sensitive components in electric agricultural robots, this study focuses on the cooling design for the motor system of a specific electric weeding robot using simulation and experiment methods. Optimal cooling fan configuration was proposed, and the safe operational fan airflow volume range at varying working ambient temperatures was determined. First, the thermal properties of the physical model, including component materials, internal heat sources, and fluid conditions, were analyzed. A three-dimensional, full-domain simulation model was then developed, and steady-state fluid-thermal coupling field calculations were performed for three different fan configurations. These simulations identified the optimal fan configuration and highlighted the motor as the primary heat-generating component. Under this configuration, the cooling performance improved by 22.7% and 22.3% compared to the other two configurations. Furthermore, based on the optimal fan setup and the operational temperature characteristics of the electric weeding robot, the relationships between motor temperature, fan airflow, and ambient temperature were analyzed and modeled. Real-time, high-precision steady-state temperature experiments were conducted to validate the airflow-motor temperature relationship, leading to the establishment of a safe operational airflow range based on the maximum allowable motor temperature. The implementation of this safe airflow range reduces the probability of motor system failure by at least 60%. This work provides theoretical and practical insights for enhancing the cooling design of motor systems in electric agricultural robots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agricultural machinery1,2can be classified into fuel-driven and electric-driven types according to their power sources. Electric agricultural machines are favored for their high energy efficiency, reduced pollution, and ease of control, making them more suitable for automation and advanced technology applications3,4. Consequently, electric-powered machinery is a prominent direction for future agricultural equipment development. Electric agricultural robots are sophisticated automated systems with advanced sensing and decision-making capabilities5,6. These robots’ motor systems include various temperature-sensitive components, such as electronic devices and motors. Exceeding the maximum allowable temperature (MAT) of these components can lead to thermal failure, which significantly undermines their reliability and longevity7. Furthermore, electric agricultural robots typically operate in environments laden with soil, weeds, and dust8,9,10,11, necessitating high levels of protection and posing significant challenges for effective cooling. The growing emphasis on lightweight and compact designs for future robots exacerbates these cooling challenges7. Therefore, designing efficient cooling systems for the motor systems of electric agricultural robots is a crucial aspect of their overall development.

Common cooling methods for motor systems include air cooling, liquid cooling, and phase change cooling12,13,14. Given the relatively low heat generation and minimal noise requirements of electric agricultural robots, air cooling is the most economical and reliable method. In natural air cooling conditions, the motor is exposed to the ambient air, which can be detrimental to the robot’s protection. Therefore, forced air cooling is commonly used. Research and optimization of forced air cooling for motor systems are well-documented. Xu et al.15 investigated the impact of blade deflection angles and outlet angles on the cooling performance of fan systems and improved cooling effectiveness by optimizing this two angles. Chang et al.16 reduced motor temperature rise by adjusting parameters of the cooling system’s flow channels. GALLONI17 examined how the number and shape of fan blades affect motor cooling performance during forced air cooling. Gao et al.18 analyzed the effects of ventilation structure dimensions and inlet air volumes on motor temperature rise. Xu et al.19 studied the impact of different airspeed on the temperature of various heat sources in a motor control cabinet under forced air cooling conditions and identified an optimal fan speed range for balancing cooling effectiveness and noise radiation.

In the design of cooling systems for electric agricultural robots, where motors and electronic control components are typically standardized, the primary focus is on optimizing fan layout and determining appropriate airflow volume. This study addresses this focus by developing incompressible fluid-thermal coupling numerical simulations and real-time high-precision steady-state temperature experiments. Utilizing these approaches, the research simulates the thermal behavior of the motor system to establish an optimal fan configuration. Furthermore, it explores the relationship between airflow volume and the maximum temperatures of critical components, leading to the formulation of an empirical equation for determining the optimal airflow volume across various ambient temperatures.

Physical model

The focus of this study is the motor system of a specific electric weeding robot, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This motor system consists of several components, including the motors, reducers, and various controllers: the drive motor controller, blade lift motor controller, blade rotation motor controller, router, RTK controller, vehicle controller, and upper computer. The two drive motors are identical, both being three-phase brushless DC (Direct Current) motors with a rated voltage of 48 V, a rated current of 28 A, and a rated power of 1038 W. The motor output shafts are connected to reducers, which facilitate power transmission. The reducers decrease the rotational speed while increasing the torque of the output shafts, enabling the weeding robot to deliver higher power at low operating speeds. Various controllers handle signal reception, processing, and the management of autonomous navigation and multi-machine coordination. The layered arrangement of these controllers ensures a compact configuration, meeting the lightweight requirements of the machine. The cooling design process of the motor system primarily focuses on the power consumption and MAT of controllers, which is independent of their functional roles. Therefore, for simplification, these controllers are numbered accordingly in this paper. To protect against environmental factors such as weeds and dust, the motor system is enclosed in a rectangular casing with dimensions of 219 mm × 375 mm × 681 mm.

(1.Motor 1 2. Reducer 1 3. Controller 1–1 4. Controller 2 − 1 5. Controller 2–2 6. Controller 2–3 7. Controller 2–4 8. Controller 3 − 1 9. Controller 3 − 2 10. Motor 2 11. Reducer 2 12. Plate)

Prior to thermal designing for the motor system, it is crucial to gain a comprehensive understanding of motor system’s thermal property, such as the component materials, internal heat sources and inside fluid condition. The motor system of this electric weeding robot primarily comprises aluminum and steel materials, as illustrated in Table 1. The internal heat sources and temperature-sensitive components include seven controllers and two motors, with relevant parameters listed in Table 2. The total thermal power generated by these sources amounts to 725.4 W, with a MAT range of 75 °C to 100 °C. Although the plates and the reducers do not generate heat and are not temperature-sensitive, they influence the flow field structure of the entire motor system and should not be overlooked.

Regarding the fluid conditions, this study uses three-dimensional incompressible flow equations to analyze the airflow within the motor system. The system experiences flow in the x, y, and z directions, with interactions between them, making a three-dimensional flow field analysis necessary for accurate results. Preliminary analysis indicates that the average velocity within the motor system is below 2 m/s, with the highest velocity occurring at the outlet fan. Based on Eq. (1), the Mach number (Ma) is calculated to be less than 0.3, which is generally considered to characterize incompressible flow in engineering applications20, where the air density is treated as constant.

Where v is the flow velocity; c is the local speed of sound, approximately 340 m/s at 15 °C and 1 standard atmospheric pressure.

In the forced air cooling process, the primary mechanism of energy transfer between the fluid and the solid surface is convection. Newton’s Law of Cooling, represented by Eq. (2), provides the fundamental formula for convective heat transfer.

Where h is the convection coefficient, W/(m²·K); A is the surface area of the object, m²; tw is the surface temperature of the object, °C; tf is the fluid temperature, °C.

Fluid velocity and flow patterns significantly impact the efficiency of heat transfer, so the accuracy of the temperature field analysis depends on the precision of the flow field. Therefore, coupled flow and heat equations are employed, as detailed in the following Eqs. 21–23:

Continuity Equation:

Momentum Conservation Equation:

Where u, v, and w is the velocities in the X, Y, and Z directions, respectively; \({S_{\text{u}}},{\text{ }}{S_{\text{v}}},{\text{ }}{S_{\text{w}}}\)is the generalized source term in the momentum conservation equation.

Energy Conservation Equation:

Where Cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure; T is the temperature; ST is the viscous dissipation term.

In the context of forced convection calculations, the Reynolds number (Re), calculated from preliminary results using Eq. (8), exceeds 105, signifying that the flow regime is turbulent. The Spalart-Allmaras (SA) model is especially effective for complex flow fields in heat exchangers, as it provides a reliable simulation of boundary layer flows and thus yields more precise temperature data for the flow field20. Consequently, this study utilizes the SA model as the turbulence model, as specified in Eq. (9) 24,25.

Where ρ is the air density, kg/m³; u is the air velocity, m/s; l is the characteristic length, m; µ is the dynamic viscosity, kg/(m·s).

Where \(\widetilde {v}\) is the turbulent eddy viscosity; ν is the molecular dynamic viscosity; \(\widetilde {\Omega }\) is the vorticity; σ, Cb1, Cb2 and k are constants; d is the length scale; and fw is the equation related to the eddy viscosity.

Simulation and results

According to physical model analysis, this study employs a three-dimensional flow-heat coupling model for simulation and utilizes the simulation results to optimize the fan layout and airflow design. The governing equations are provided in Eqs. (3)-(9). Figure 2 illustrates the three-dimensional computational model of the motor system. To improve computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy, the model simplifies various components, such as the motor, reducer, and controllers, by removing non-critical geometric features, including bosses, grooves, fillets, and mounting structures, which have minimal impact on the flow and temperature fields. However, the heat sink structure of the controllers is retained for accuracy. The housing of the motor system is represented as a boundary with negligible thickness. This simplification facilitates mesh generation and ensures compliance with quality standards for alignment, volume, and skewness.

The simulation incorporates appropriate boundary conditions and heat source parameters based on the characteristics of the components. The housing is assigned a constant heat flux boundary condition, with the convection coefficient set to 10 W/(m²·K), consistent with typical values for natural convection heat transfer coefficients26,27. Power dissipation in the motor is attributed to Joule heating and eddy current losses, while the controllers’ power dissipation is primarily caused by Joule heating. The heat source parameters are defined according to the specific power dissipation characteristics of the motors and controllers.

Optimal fan configuration design

Based on the temperature rise characteristics of the motor system and its design structure, a 24 V DC-powered axial fan was selected for this study. The fan measures 140 mm × 140 mm, with a rated power of 36.4 W and a maximum airflow of 350 CFM. Additionally, the fan features speed control, stall protection, and waterproof and dustproof capabilities, ensuring its suitability for the operational conditions of the weeding robot. The arrangement of fans can significantly influence the internal airflow structure, thereby impacting the heat dissipation performance of the motor system. This study selects three fan configurations based on the operating characteristics of the motor system. It analyzes the temperature and airflow distributions of different components under identical temperature and airflow conditions to determine the optimal fan configuration.

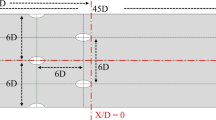

The upper part of the motor system’s housing (positive y-axis) is prone to intrusion by rain and dew, while the lower part (negative y-axis) is susceptible to weed penetration. The rear side (negative x-axis) connects to the main vehicle structure, making these areas unsuitable for openings. To ensure clean air intake, the inlet fan is placed on the upper left side of the motor system. A longer airflow path inside the motor system improves heat dissipation efficiency. Therefore, this paper proposes three different outlet fan configurations, as shown in Fig. 3.

The relative performance of the fan configurations is independent of ambient temperature and airflow volume. Therefore, during the fan configuration optimization process, the ambient temperature and airflow volume were preliminarily determined. The ambient temperature was set to 40 °C, meeting the requirements for extreme summer operating conditions. The total thermal power of the motor system was 725.4 W, and using Eq. (10) 28, the inlet fan airflow was calculated to be 0.03 m³/s, or 63.5CFM. The outlet fan airflow was equal to the inlet fan airflow.

where q is the fan airflow rate, m³/s; Q is the heat dissipation, W; ρ is the air density, 1.29 kg/m³; Cp is the specific heat capacity of air, 1005 J/(kg·K); Δt is the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet, initially set to 20 K .

Based on the previously discussed fan configurations, temperature conditions, and airflow parameters, three distinct operating cases were developed: Case 1, Case 2, and Case 3, each corresponding to one of the three outlet fan configurations. These cases involve coupled calculations of velocity and temperature fields, with the results representing steady-state conditions suitable for the extended operation of the electronic weeding robot. Figure 4 presents the results for Case 1, with temperature and velocity vector analyses conducted on the cross-section at x = 109.5 mm. Due to the high power diffusion of the two motors, their temperatures are significantly higher than those of other components. Motor 1 has a lower temperature than Motor 2 for the following reasons:1. The temperatures on either side of Motor 1 are lower than those on either side of Motor 2. Motor 1 is positioned at the inlet, where the air temperature ranges from 40 °C to 50 °C. After passing through internal heat sources, the air reaching Motor 2 is warmer, with temperatures ranging from 60 °C to 70 °C.2. The airflow at the inlet fan is concentrated, whereas the airflow at the outlet fan is dispersed. The concentrated airflow at the inlet fan is directed toward the upper part of Motor 1, resulting in a thinner temperature boundary layer and more effective heat dissipation. In contrast, the dispersed airflow at the outlet fan leads to a thicker temperature boundary layer around Motor 2, resulting in less effective but more uniform heat dissipation.

The temperature of the seven controllers is influenced by both the airflow structure and power diffusion. The formation of negative pressure zones behind Motor 1 and Reducer 1, resulting from their obstruction of airflow, generates vortices. These vortices increase the convective heat transfer time between the air and temperature-sensitive components, thereby aiding in component cooling. Controller 1–1 and Controller 3 − 1 are affected by local vortices, resulting in thinner temperature boundary layers and lower temperatures. Controllers 2−1 and 2–2, equipped with heat dissipation fins, exhibit increased convective heat transfer areas, resulting in lower operating temperatures.

Figure 5 compares the MAT of temperature-sensitive components with the calculated maximum temperature in three cases. Among the different fan configurations, the temperature of the controllers exhibits minimal variation and remains lower than the MAT. However, the temperatures of the two motors significantly exceed the MAT, identifying Motor 1 and Motor 2 as critical components within the motor system that require enhanced cooling strategies to bring their temperatures within the permissible range. The temperature of Motor 1 remains consistent across all three cases, whereas the temperature of Motor 2 in Case 1 is significantly lower compared to the other two cases. Figure 6 illustrates the velocity vector field at the z = 570 mm cross-section for the three cases. This cross-section intersects with Motor 2 and the outlet in both Case 2 and Case 3. In Case 1, the flow field vectors predominantly align along the negative z-axis, with smaller components in the xy-plane. The velocity vectors in Case 1 are not only higher in magnitude but also more evenly distributed, with an average velocity of 0.74 m/s. In contrast, despite the increase in velocity vector components at the outlets in Case 2 and Case 3, the airflow velocity at the boundary layer of Motor 2 is lower compared to Case 1, with average velocities of 0.66 m/s and 0.49 m/s, respectively. Motor 2 dissipates heat primarily through convective heat transfer, and according to Eq. (2), the amount of convective heat transfer is proportional to the surface flow velocity. Therefore, Motor 2’s convective heat transfer is greatest in Case 1, resulting in the lowest temperature. By comparison, the temperature of Motor 2 in Case 1 is 22.7% lower than that in Case 2 and 22.3% lower than that in Case 3. Based on this analysis, Case 1 is selected as the optimal fan configuration for cooling.

Airflow volume design

From the preceding analysis, it is evident that Motor 1 and Motor 2 are at risk of overheating within the motor system. To mitigate this risk, optimizing the airflow volume through the inlet and outlet fans can effectively reduce the motors’ maximum temperatures to within the MAT, thereby ensuring the reliable operation of the motor system. Considering that the operating ambient temperature of the weeding robot typically ranges from 25 °C to 40 °C, this study selects four representative temperatures (25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C) for airflow volume design. Based on Eq. (10) and the fan size, the range of inlet and outlet airflow volumes is determined to be 100–350 cfm. Using coupled fluid-thermal simulations and characteristic data fitting, the relationship between the maximum temperatures of Motor 1 and Motor 2 and the inlet and outlet airflow volumes is established under varying ambient temperatures. This relationship, combined with the motors’ MAT, is then used to determine the optimal ranges for the inlet airflow volume (Qin) and outlet airflow volume (Qout).

Across varying ambient temperature conditions, the influence of airflow volumes on the motor system’s temperature remains largely consistent. In practical operation, excessively high ambient temperatures impede the dissipation of heat from the internal system. Therefore, this paper analyzes the simulation results under the most extreme condition (an ambient temperature of 40 °C) to identify the relationship between motor temperature and fan airflow volume. The Qout was varied between 100 cfm and 350 cfm in 50 cfm increments, resulting in six simulation groups. For each group, the Qin ranged from 100 to 350 cfm, as shown in Figure 7.

As seen in Figure 7(a), when the Qout remains constant, increasing the Qin results in an overall temperature reduction of Motor 1, with a maximum decrease of 48 °C. This indicates that Qin have a significant impact on the temperature characteristics of Motor (1) In contrast, comparing the results at different Qout reveals that the Qout has a minimal effect on the temperature of Motor 1, which can be almost disregarded. For Motor 2, as shown in the temperature curves in Fig. 7(b), a similar trend is observed: as the Qin increases, the temperature of Motor 2 decreases. However, compared to Motor 1, this trend is less pronounced, with temperature differences ranging from 19 °C to 39 °C. Additionally, comparing the temperature variation curves for different Qout shows that increasing the Qout has a more significant impact on the temperature of Motor (2) When the Qout is increased from 100 to 350 cfm, the temperature of Motor 2 decreases by 24–41 °C. This analysis highlights that the effect of fan airflow volumes on the temperature characteristics of Motor 2 is more complex and requires special attention.

Airflow effect on motor 1

To investigate how airflow volume affects the temperature rise characteristics of Motor 1, simulations were performed with the Qin as the variable, across various ambient temperature conditions. Qin was varied between 100 cfm and 350 cfm in 50 cfm increments, results are shown in Figure 8.

As seen in Figure 8, at all four ambient temperatures, the maximum temperature of Motor 1 decreases as the Qin increases. For Qout ranging from 100 to 350 cfm in 50 cfm increments, the variance of temperature for the same Qin was computed, and the overall variance was found to be minimal. Moreover, below the MAT, the variance was generally less than 0.19, further confirming that Motor 1’s temperature is primarily influenced by Qin, with little dependence on Qout. Additionally, comparisons across different ambient temperature conditions show that Motor 1’s temperature is significantly higher in high-temperature environments. This is because, in convective heat transfer calculations, besides the airflow velocity around the motor system, the surface temperature difference is a key factor in determining the cooling efficiency. As ambient temperature increases, the temperature difference decreases, reducing the temperature gradient within the surface boundary layer, which hinders convective heat transfer. Therefore, Motor 1’s temperature characteristics within the system are determined by both Qin and ambient temperature.

Based on the preceding analysis, the data point with Qout=200 cfm was selected as the reference for curve fitting. As shown in Figure 8, the R-squared values for all four fitted equations exceed 0.99, demonstrating that each equation accurately models the relationship between Motor 1’s temperature and Qin. By synthesizing the characteristics of these four fitted equations, the relationship between Motor 1’s maximum temperature, ambient temperature, and Qin can be established, as represented in Eq. (11). According to Motor 1’s MAT, the minimum required Qin for various ambient temperatures can be determined.

Where T1 is the maximum temperature of Motor 1, °C, Qin is the inlet airflow volume, cfm; Tout is the ambient temperature, °C.

Airflow effect on motor 2

To analyze the effect of airflow on the temperature characteristics of Motor 2, simulations were conducted using Qin and Qout as variable, across various ambient temperature conditions. Considering the motor system’s component layout and airflow characteristics, along with standard fan parameters, Qin and Qout were varied between 100 cfm and 350 cfm in 50 cfm increments. The results are shown in Figure 9. At all four ambient temperatures, the maximum temperature of Motor 2 decreases with the increase in both Qin and Qout. Among these, Qout has a more significant impact, while the influence of Qin is relatively minor. The airflow range below the MAT plane in Figure 9 represents the airflow range required for the stable operation of Motor 2.

Comparing the results under different ambient temperature conditions reveals that as the ambient temperature increases, the maximum temperature of Motor 2 also rises, and the airflow range that satisfies the stability requirements narrows. To quantitatively describe the effect of Qin and Qout on motor temperature under different ambient conditions, two parameters were defined: \(\Delta {t_{in - r}}\) and \(\Delta {t_{out - r}}\)。\(\Delta {t_{in - r}}\)represents the maximum temperature difference of Motor 2 when varying the inlet airflow while keeping the outlet airflow constant. Each outlet airflow yields a corresponding \(\Delta {t_{in - r}}\), which is expressed as a range of values. Similarly, \(\Delta {t_{out - r}}\) represents the maximum temperature difference of Motor 2 when varying the outlet airflow while keeping the inlet airflow constant, and the results are also expressed as a range of values. The calculated results are shown in Table 3. The ranges of \(\Delta {t_{in - r}}\) and \(\Delta {t_{out - r}}\)are the same under different ambient temperature conditions, indicating that ambient temperature affects only the temperature value of Motor 2, not the range of temperature variation. Based on the analysis of Eq. (3) to (7), when Qin and Qout are same, the velocity vector distribution in the flow field and the temperature gradient distribution are identical. Therefore, ambient temperature affects only the value of the maximum temperature and has a linear influence.

Based on the preceding analysis, the maximum temperature of Motor 2 can be expressed as a function of ambient temperature, Qin, and Qout. The effect of airflow volumes is represented in an exponential form, while the effect of ambient temperature is represented linearly. Figure 9 illustrates the fitted temperature of Motor 2 under various ambient temperature conditions. The fitting relationship is described by Eq. (12) with R-squared values exceeding 0.92.

Where T2 is the maximum temperature of Motor 2, °C Tout is the ambient temperature, °C; Qin is the inlet airflow volume, cfm; Qout is the outlet airflow volume, cfm.

Experiment and results

Experimental methodology

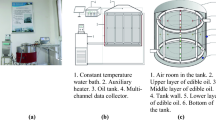

To experimentally validate the aforementioned simulation results, an experimental platform was constructed based on the physical model of the motor system, using the electric weeding robot. The platform consists of three main components: the robot’s motor system, the air cooling system, and the data collection system, as shown in Fig. 10; Table 4. The motor system is composed of the motor, reducer, and controller, which ensures the weeding robot can travel at a maximum speed of 1 m/s. This section serves as the primary focus for temperature rise during the data collection process. The air cooling system includes two ports machined into the motor system casing and two axial fans with control board. Based on the simulation results from Sect. 2.1, the fan layout was designed according to case1. Considering the operational characteristics of the weeding robot, the diameters of the intake and exhaust ports were set at 140 × 140 mm, and a high-flow axial fan was selected with an adjustable air volume. This allows for real-time control of the inlet and outlet airflow. During installation, flexible gaskets were added at fixed positions to reduce vibration and stabilize the airflow. The data collection system comprises a temperature test chamber and a temperature recorder with high-precision temperature sensors. The temperature text chamber is used to control and record the ambient temperature. The temperature recorder is used to monitor the temperature data of key components such as the motor and controller. To ensure measurement accuracy, point-based temperature sampling was chosen for data collection. As noted in the motor simulation results, the temperature distribution across the motor surface is uneven, primarily due to the influence of heat source location and the thermal properties of the motor materials. Although the metal casing provides some thermal uniformity, temperature variations still exist at different locations on the motor surface. Therefore, during the experiment, multiple measurement points were arranged on the object to monitor the temperature distribution.

Relationship between maximum temperature of Motor 2 and airflow volumes at different ambient temperature (The original data points are obtained from simulations, while the fitting surface represents the temperature distribution derived through fitting equations. MAT represents maximum allowable temperature of Motor 2, which is 100 ℃).

Based on preliminary research and simulation results, the primary heat sources in the motor system of the weeding robot are the left and right drive motors during operation. Therefore, this study focuses on the relationship between the temperature characteristics of the drive motors and the fan volumes of the air cooling system. In the experiment, the robot’s speed was set to 1 m/s, corresponding to the motors operating at maximum output power for 1.5 h. Simultaneously, a temperature recorder was used to continuously monitor the temperatures of both motors. High-precision thermocouples were employed to measure the surface temperature of the motors at specific points, with the temperature measurement points arranged as shown in Fig. 11. Each motor had two temperature measurement points placed uniformly at the top, and six points evenly distributed along the sides to ensure reliable data and minimize human measurement errors. Additionally, four temperature measurement points were scattered around the robot to monitor the ambient temperature in real-time. To accurately simulate real operating conditions during the experiment, the weeding robot was fixed to a nylon board on the test bench, ensuring that the robot encountered a frictional resistance similar to that of a real wheel on the ground. Since the coefficient of dynamic friction on actual grass and soil is approximately 0.3, a nylon board with a friction coefficient of 0.4 was chosen for the experimental setup. Given the influence of ambient temperature on motor temperature, the test bench was placed inside the temperature text chamber.

Experimental results and analysis

The simulation results presented in this study reveal the optimal fan layout and the influence of airflow on motors under varying ambient temperature conditions. The simulation of the fan layout offers an optimal design solution while reducing the cost of the cooling system design. Additionally, the simulation of airflow ranges across different external temperatures enables rapid determination of safe airflow limits and the development of an airflow-motor temperature equation. This section validates the airflow effects on Motors 1 and 2 under variable ambient temperatures using experimental data, thereby establishing the safe airflow range for the motor system.

The experiments were conducted with ambient temperature as the independent variable, setting four temperature conditions: 25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C. For each condition, the inlet and outlet airflow volumes were set to 160, 210, and 280 cfm, respectively, with a total of nine experimental sets. After 1.5 h, the temperature rise rate at each measurement point on Motors 1 and 2 slowed down, indicating that the motor temperatures had stabilized. The maximum temperature from the measurement points was considered as the motor’s peak temperature and was compared with the simulation results shown in Figure 8 and 9. Given that the temperature variation patterns were consistent across different conditions, the comparison focuses on the extreme temperature conditions of 40 °C (maximum) and 20 °C (minimum).

As shown in Figure 12, the experimental and simulation results exhibit similar trends. The temperature of Motor 1 is solely affected by the inlet airflow volume. As the inlet airflow increases, the temperature of Motor 1 decreases, and the relationship between the two follows an exponential distribution. The experimental temperature of Motor 1 was lower than the simulation results due to the limited placement of measurement points in the experiment, which may not have captured the maximum temperature point predicted by the simulations.

Given the consistent temperature variation pattern of Motor 2 across different ambient temperature conditions, this study provides a comparison of experimental and simulation results at 25 °C. As illustrated in Figure 13, both the experimental and simulation results reveal comparable trends. The temperature of Motor 2 is influenced by both the inlet and outlet airflow, with a more pronounced effect from the outlet airflow. The relationship between the temperature of Motor 2 and the inlet and outlet airflow adheres to an exponential distribution. The experimental data are lower than the simulation results, which can be attributed to the limited placement of measurement points in the experiments. Furthermore, the resistance and power levels during the experimental setup may not have been fully realized. The maximum relative error across all experimental data points is 8.27%, while the average relative error stands at 4.8%. This analysis confirms that the simulation results effectively replicate the physical principles governing airflow and temperature within the motor system.

In this study, the Qin and Qout are controlled between 100 and 350 cfm. The objective is to determine the specific airflow ranges that ensure the stable operation of Motor 1 and Motor 2 within these controlled airflow limits. The MAT for both motors is 100 °C based on the previous analysis, Figure 14 presents the operational airflow ranges for the two motors based on simulation and experiment. Under four different ambient temperature conditions, the minimum Qin is obtained from Eq. (11), while the maximum is determined by the controlled inlet airflow limits. The minimum Qout is determined by the fitting equation, with the maximum also set by the controlled limits. The fitting equation represents the slope when Motor 2 remains within the MAT range, with R-squared values exceeding 0.99.

When ambient temperature is high, the safe airflow range for Motor 1 and Motor 2 becomes smaller. This occurs due to the following reasons: at higher ambient temperatures, the temperature gradient between the motor and the surrounding air decreases. According to the governing Eq. (2), increasing the airflow velocity within the motor system enhances the convective heat transfer coefficient between the motor and the air, thereby ensuring the safe operation of the motor. However, this adjustment reduces the safe airflow range at both the inlet and the outlet. As the ambient temperature increases, the ratio range of outlet safe airflow to inlet safe airflow gradually decreases. Specifically, at ambient temperatures of 40 °C, 35 °C, 30 °C, and 25 °C, the ratio ranges are 0.95–1.1, 0.73–1.6, 0.6–2.0, and 0.4–2.2, respectively. This trend can be explained by the following factors: 1.As the ambient temperature increases, the minimum outlet safe airflow rises under the condition of maximum inlet safe airflow. This leads to an increase in the lower bound of the ratio range. 2.With rising ambient temperature, the minimum inlet safe airflow decreases, while the maximum outlet safe airflow remains constant. Consequently, the upper bound of the ratio range is reduced. Let P represent the probability of motor failure due to prolonged operation within the controlled temperature limits. Under ambient conditions of 40℃, 35℃, 30℃, and 25℃, the corresponding values of P are 99.7%, 90.0%, 74.5%, and 60.0%, respectively. The calculations presented in this study demonstrate that the probability of motor failure caused by overheating during extended operation can be reduced by at least 60%. Figure 14 provides the expressions for the ranges of Qin and Qout under the four ambient temperature conditions, as shown in Table 5.

(The area enclosed by the blue line represents the airflow range where Motor 2’s temperature remains below 100 °C, and the area enclosed by the red line for Motor 1. The green overlap shows the range where both motors’ temperatures stay below 100 °C. The yellow solid line is the fitting equation, the coordinates marked in the figure represent the corner points of the safe airflow range)

Conclusion

This study investigated the air-cooling design of the motor system in an electric weeding robot using incompressible fluid-thermal coupling simulations and real-time high-precision steady-state temperature experiments.Three fan cooling configurations were designed, and four ambient temperatures (25 °C, 30 °C, 35 °C, and 40 °C) were selected, to investigate the effects of fan configurations and airflow volumes on the motor system’s cooling performance. The key conclusions are as follows:

-

1.

Three fan configurations were developed, based on the motor system’s temperature requirements for long-term operation and the structural design of the weeding robot, Temperature analysis showed that both motors exceeded the maximum allowable temperature among three configurations, making them critical for system safety. Case1(symmetrical fan layout) significantly enhanced convective heat transfer by accelerating boundary layer flow at the outlet motor, reducing its temperature. In Case 1, motor’s temperature was 22.7% lower than in Case 2 and 22.3% lower than in Case 3, confirming Case 1 as the optimal fan configuration.

-

2.

In the selected fan configuration, the temperature of Motor 1 (near the inlet fan) is primarily influenced by inlet airflow volume, with its maximum temperature decreasing as the inlet airflow volume increases. In contrast, the temperature of Motor 2 (near the outlet fan) is influenced by both inlet and outlet airflow volumes. As airflow volumes increase, Motor 2’s temperature decreases significantly, with outlet airflow volume having a more pronounced effect on its maximum temperature than inlet. The relationship between motor temperature and airflow volume followed an exponential trend, while ambient temperature effects were linearly additive.

-

3.

Optimal airflow volume ranges were determined for ambient temperatures between 25 °C and 40 °C, reducing the risk of motor failure due to overheating during prolonged operation by at least 60%.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mac, T. T. et al. Intelligent agricultural robotic detection system for greenhouse tomato leaf diseases using soft computing techniques and deep learning. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 23887. (2024).

Yang, L. et al. Multi-area collision-free path planning and efficient task scheduling optimization for autonomous agricultural robots. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 18347. (2024).

Tian, W. et al. Design and test of electric micro-facility agricultural operation machinery. Agric. Equip. Veh. Eng. 55(8), 19–23. (2017).

Huang, X. H. et al. Prospects for purely electric construction machinery: Mechanical components, control strategies and typical machines. Autom. Constr. 164, 105477. (2024).

Zhang, M. Introduction to Agricultural robot 2–3 (China Agricultural University, 2023).

Diego, T. F. et al. Towards autonomous mapping in agriculture: A review of supportive technologies for ground robotics. Rob Auton Syst 169, 104514. (2023).

Gao, L. L., Chen, S. & Zheng, G. F. A Review of the research status of robotic thermal control technology. J. Mech. Sci. Technol 43(5), 737–749. (2024).

Song, Y. M. et al. Development status and trend of new energy intelligent agricultural machinery and Equipment. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 62(1), 1–6. (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Orchard electronic control system design of the sprayer and test. Journal of agricultural mechanization research 45(6), 76–81. (2023).

Wang, J. F. et al. Applying fertilizer in paddy field electric double row weeding machine design and test. J. Agric. Mach. 49(7), 46–57. (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. Electric remote control hedge trimmer design. Journal of Chinese agricultural mechanization 39(3), 19–25. (2018).

Tang, Y. et al. The research status quo and trend of development of motor cooling system. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 32(1), 1135–1150. (2021).

Han, Y. L. et al. Thermal Control of Electronics for Nuclear Robots via Phase Change Materials. Energy Procedia 75, 3301–3306. (2015).

Han, Y. L. et al. Protection of electronic devices on nuclear rescue robot: Passive thermal control. Appl. Therm. Eng 101, 224–230. (2016).

Xu, Y. M. et al. Heat transfer characteristics of external ventilated path in compact high-voltage motor. Int. j. heat mass transf 124(4), 1136–1146. (2028).

Chang, C. C. et al. Air cooling for a large-scale motor.Appl. Therm. Eng 30(11–12), 1360–1368. (2010).

Galloni, E. et al. CFD analyses of a radial fan for electric motor cooling. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog 8, 470–476. (2018).

Gao, J. et al. Forced ventilation on high torque at low speed permanent magnet motor application analysis. Mot. Control 26(11), 58–64. (2022).

Xu, L. J. et al. Industrial robot electrical control cabinet of heat flow field analysis. Journal of machine tools and hydraulic 46(15), 32–36. (2018).

Wang, H. B. et al. Improvement of shock wave and compressibility effect of SST turbulence model. Chinese J. Aeronaut 45(3), 128694–128694. (2024).

Zeeshan, K. et al. Steady flow and heat transfer analysis of Phan-Thein-Tanner fluid in double-layer optical fiber coating analysis with Slip Conditions. Sci. Rep. 37, 729v740. (2016).

Elshaer, A. M. et al. Boosting the thermal management performance of a PCM-based module using novel metallic pin fin geometries: Numerical study. Sci. Rep. 13, 10955. (2023).

Wang, Y. K. ANSYS Icepak Electronic heat Dissipation Basic Course 1–435 (National Defense Industry, 2015).

Zhou, D. G. et al. Numerical simulation of airfoil separation flow with improved SA model. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronsutics 38(10), 1384–1388. (2012).

Xiao, F. et al. Research on improved delayed separation eddy simulation method based on SA model. Aeronautical Computing Technology 54(2), 52–56. (2024).

Meng, F. k., Xu, C. X. & Sun, Y. T. Transient characteristics of closed space thermoelectric cooler with heating Element. Journal of Zhejiang University (Engineering and Technology Edition) 57(1), 55–62. (2023).

Jiao, X. Q., Zhai, F. & Liu, D. H. Load thermal design and analysis based on Solidworks. Journal of electronics 43(2), 396–401. (2020).

Li, Y. & Zheng, Q. H. High-power IGBT radiator design of simulation and experiment research. Journal of power 16(1), 107–111. (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shusong Wang and Peng Wang wrote the main manuscript text, Heng Wang prepared field experiment and Haiyuan Wang prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Wang, H., Wang, P. et al. Air cooling design for the motor system of electric agricultural robots. Sci Rep 15, 7884 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90323-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90323-6