Abstract

Sinomenium acutum, a traditional medicinal plant, has been utilized for millennia to alleviate various forms of rheumatic pain symptoms. The structurally diverse benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) found in S. acutum are the primary contributors to its therapeutic efficacy, with sinomenine being the principal bioactive constituent. In this study, we employed an integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic approach to investigate BIA biosynthesis in S. acutum. Transcriptome sequencing, functional annotation, and differential gene expression analysis were combined with metabolite profiling to predict biosynthetic pathways of structurally diverse BIAs and screen candidate genes. Metabolomic analysis revealed significant stem-enriched accumulation of BIAs compared to leaves. Furthermore, we proposed a biosynthetic pathway of sinomenine and hypothesized that 34 key candidate genes, including cytochrome P450 (CYP450s), reductases, 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-ODDs), and O-methyltransferases (O-MTs), might be involved in its biosynthetic process. This study provides a foundation for understanding the biosynthesis of structurally diverse BIA compounds in S. acutum and offers critical insights for future characterization of functional genetic elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sinomenium acutum, a traditional medicinal plant belonging to the woody vine type in the sinomenium genus of the Menispermaceae family1. S. acutum has a lengthy growth cycle and is predominantly found in the wild, garnering considerable attention for its economic and medicinal value2. The rattan of S. acutum is renowned for its durability, exceptionally long branches, and smooth feel, making it an excellent natural material for weaving various utensils. This traditional craft is recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage, with an annual consumption exceeding one million tonnes. Additionally, the dried stems of S. acutum, known as Qing fengteng in traditional Chinese medicine, have been used for millennia to alleviate rheumatic pain2. In modern medicine, S. acutum is employed in formulations such as injections and extended-release tablets, effectively treating conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, chronic nephritis, and gout3. The primary active constituents of S. acutum are BIAs, with sinomenine being the most notable. Sinomenine, classified as a morphinan alkaloid based on its skeletal structure, exhibits significant anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and immunosuppressive effects. It is widely used in sinomenine hydrochloride preparations for treating rheumatoid arthritis, demonstrating an overall efficacy rate of 89.0%4. Moreover, S. acutum contains various other BIAs, including 1-benzylisoquinoline scaffold (S)-norcoclaurine, known for its anti-HIV activity5, proaporphine stepharine, which possesses anti-aging, anti-hypertensive, and anti-viral functions6, aporphine alkaloid (S)-magnoflorine, with anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fungal activities7, and protoberberine alkaloids (S)-corydalmine and (S)-scoulerine. The former shows promise in alleviating bone cancer pain and reducing morphine tolerance8, while the latter exhibits potential in inhibiting various human cancer cell lines9. The diverse BIAs in S. acutum constitute the foundation of its therapeutic efficacy, underscoring the importance of comprehensive studies on their biosynthesis and metabolism to understanding the mechanisms behind the plant’s active ingredient formation.

Significant advancements have been achieved in researching the biosynthetic pathway of BIAs. For several prominent molecules, such as morphine, noscapine, and papaverine, the biosynthetic pathways have been fully elucidated, and heterologous production has been successfully achieved10. These BIAs typically originate from a common biosynthetic pathway, utilizing tyrosine as the initial precursor to generate two tyrosine derivatives, dopamine and 4-hydroxyphenylglyoxal (4-HPAA). Subsequently, a condensation reaction catalyzed by norcoclaurine synthase (NCS) forms (S)-norcoclaurine11, which is then converted by two methyltransferases (norcoclaurine 6-O-methyltransferase, 6OMT and coclaurine N-methyltransferase, CNMT) into (S)-coclaurine and (S)-N-methylcoclaurine12. Further hydroxylation at the C3’ position of (S)-N-methylcoclaurine, mediated by a cytochrome P450 ((S)-N-methylcoclaurine 3’-hydroxylase, NMCH), yields (S)-3′-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine13. Subsequent conversion by a methyltransferase (3’-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4’-hydroxylase, 4’OMT) leads to the production of the crucial intermediate (S)-reticuline14, which is pivotal in the formation of various BIAs, including morphine, codeine, berberine, and magnoflorine. The biosynthesis of most BIAs in S. acutum involves the above pathway15. Starting from (S)-reticuline, diverse skeleton types of BIAs are formed through the catalysis of cytochrome P450 (CYP450), methyltransferase, and reductase genes. Examples include protoberberine alkaloids like sanguinarine, aporphine alkaloids such as magnoflorine, and morpholine alkaloids like sinoacutine10. The biosynthetic pathway of sinomenine remains unclear, although a recent report suggests that MdCYP80G10 from Menispermum dauricum catalyzes the coupling of the C2’-C4 phenol of (S)-reticuline, followed by rearrangement to produce sinoacutine16. Further steps likely involve the catalysis of genes encoding reductase and methyltransferase to yield sinomenine.

Further efforts are required to elucidate the biosynthetic pathways of proaporphine, aporphine, and morpholine alkaloids in S. acutum. Currently, the sequence information of key enzymes in these biosynthetic pathways remains unknown, significantly impedes the synthesis and application of pharmacologically active compounds. Given its richness in BIAs, S. acutum has emerged as an ideal plant material for studying the biosynthesis of relevant BIAs compounds. However, the genome of S. acutum has not yet been sequenced, and genetic resources remain limited. Here, we conducted transcriptome sequencing, assembly, and functional annotation of S. acutum stems and leaves using the BGI DNBSEQ-T7 high-throughput sequencing platform. Combined with metabolomics data, we hypothesized the biosynthetic pathways and candidate genes of BIAs such as stepharine, fangchinoline, artabotrine, and 8-oxyberberine in S. acutum. Particularly, we investigated the biosynthetic pathway of the primary active compound sinomenine and screened key candidate genes, laying the foundation for further exploration into the biosynthesis of structurally diverse BIAs in S. acutum.

Results

Transcriptome sequencing and functional annotation of S. acutum

To investigate the key enzyme genes involved in the BIAs biosynthetic pathway in S. acutum, we extracted RNA from six samples of stems and leaves, constructed the corresponding cDNA library, and performed sequencing using the BGI high-throughput sequencing platform DNBSEQ-T7. After filtering the raw sequencing data, a total of 255,571,722 clean reads were obtained, and the mean Q20 and Q30 rates were 98.44%±0.11% and 95.50%±0.23%, respectively, and the mean GC content was 46.57%±0.18%, indicating high sequencing quality (Table S1). Given the absence of genomic information for S. acutum, the Trinity software was employed to assemble the clean reads, resulting in 181,935 transcripts with lengths ranging from 184 to 11,998 bp and an average length of 1,145 bp (Table S2). After clustering to remove redundancy and sequences with ≥ 95% similarity, 71,003 unigenes were identified. The N50 length of these unigenes was 1,469 bp, with lengths ranging from 199 to 11,998 bp and an average length of 816 bp (Fig. 1A, Table S2). Gene completeness was evaluated using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs)17 (Table S3), and coding region sequences (CDSs) were predicted for all unigenes, resulting in 41,118 CDSs. The length distribution of CDS was shown in Fig. S1. To maximize the identification of unique functional genes from the transcriptome, unigenes were annotated using multiple databases including GO, KEGG18,19,20, KOG, NR, PATHWAY, Pfam, and Uniprot (Table S4). Among the 71,003 unigenes, 21,761 (29.95%) were annotated in at least one database. Specifically, 21,903 unigenes (28.82%) were annotated in the NR database, followed by 21,716 (28.57%) in the Uniprot database, 11,626 (21.88%) in the Pfam database, 11,282 (18.79%) in the GO database, 1,666 (12.72%) in the KEGG database18, 1,967 (6.54%) in the PATHWAY database, and 1,309 (3.04%) in the KOG database. For GO analysis, a total of 38,536 unigenes were functionally annotated across molecular function, cellular component, and biological process, as some unigenes were annotated by multiple GO functions (Fig. 1B, Table S5). Within the molecular function category (11,022, 49.36%), the largest proportion of unigenes was associated with ATP binding (1,016, 10.60%), followed by metal ion binding (935, 4.92%) and zinc ion binding (716,3.76%). In the cellular component category (1,876, 25.63%), the most prevalent unigenes were linked to integral component of the membrane (1,404, 34.47%), followed by nucleus (1,514, 15.33%) and cytoplasm (602, 6.10%). In the biological process category (1,638, 25.01%), the highest number of unigenes were involved in the regulation of transcription, DNA-templated (346, 3.59%), followed by translation (265, 2.75%) and carbohydrate metabolic process (241, 2.50%). For KEGG analysis, due to the presence of one unigene annotated by multiple KEGG functions, a total of 11,631 unigenes were annotated across five aspects (Fig. 1C, Table S6). Specifically, 448 (3.85%) unigenes were annotated to cellular processes, 431 (3.71%) to environmental information processing, 1,266 (19.48%) to genetic information processing, 1,218 (70.66%) to metabolism, and 268 (2.30%) to organismal systems. Among these, 1,180 unigenes were annotated to be involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis, with 47 unigenes involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, 39 unigenes specifically associated with isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, 18 unigenes linked to tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis, and two unigenes involved in the indole alkaloid biosynthesis. These findings suggest a potential role for these unigenes in the biosynthesis of active compounds in S. acutum.

Transcriptome assembly and functional annotation of unigenes in S. acutum. (A) Length distribution of filtered unigene after redundancy removal. (B) GO classification of annotated unigenes, categorized into biological process, molecular function, and cellular component. (C) KEGG pathway annotation of unigenes.

Analysis of differential accumulation of metabolites in different tissues of S. acutum

To further investigate the biosynthetic pathways of BIAs with diverse structures in S. acutum, UPLC-MS/MS in positive and negative ion mode was employed to detect alkaloids in different tissues of S. acutum. Metabolites were characterized by integrating the self-generated database and multiple response monitoring (MRM), leading to the identification of 295 metabolites. These metabolites were categorized into 11 groups based on their secondary classification, including phenolamine (45, 15.25%), pyrrole alkaloids (11, 3.73%), plumerane (20, 6.78%), quinorisidine alkaloids (1, 0.34%), terpenoid alkaloids (4, 1.36%), isoquinoline alkaloids (118, 40.00%), piperidine alkaloids (5, 1.69%), tropane alkaloids (1, 0.34%), quinoline alkaloids (5, 1.69%), pyridine alkaloids (4, 1.36%), other alkaloids (81, 27.46%) (Table S7). Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed to compare the leaf group and stem group of S. acutum. The results showed clear separation between the two groups, with distinct clustering (Fig. S2). The OPLS-DA graph further illustrated differences in metabolite profiles between the leaf group and stem group (Fig. S3). The comparative analysis was conducted with the leaf group as the control group and the stem group as the experimental group (Table S8). Metabolites with a fold change ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5 were selected, identifying 155 significantly different metabolites, including 97 up-regulated and 58 down-regulated. Specifically, 69 significantly different isoquinoline alkaloid metabolites were identified, with 60 up-regulated and 9 down-regulated instances, suggesting that isoquinoline alkaloids are predominantly enriched in the stems rather than the leaves. However, the metabolomics data indicated a low abundance of sinomenine, a crucial active ingredient in S. acutum, possibly due to its relatively lower content in both tissues and the limited sample size used in the analysis. Further analysis using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS confirmed the presence of key compounds in the sinomenine biosynthetic pathway, including (S)-reticuline, sinoacutine, and sinomenine (Table S10, Fig. S4). These compounds exhibited higher accumulation in the stems, consistent with the overall trend of isoquinoline alkaloids enrichment. These spatial variations in metabolite distribution between leaves and stems provide a foundation for differential gene analysis and the screening of key enzyme genes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of BIAs in S. acutum.

Differentially expressed genes in the stems and leaves of S. acutum

To investigate differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different tissues of S. acutum, fragments per kilobase per million bases (FPKM) values were calculated to quantify gene expression levels21. The dispersion of unigene expression levels within individual samples and the comparative expression profiles across samples are shown in Fig. 2A. Differential expression analysis was performed using read count data, with the stem group as the control and the leaf group as the experimental group. A total of 5,795 DEGs were identified, including 2,375 up-regulated and 3,420 down-regulated unigenes (Table S11). The results indicated greater enrichment of DEGs in the stems. Volcano plots were employed to visualize the differential expression levels of unigenes (Fig. 2B).

Tissue-specific gene expression profiles in S. acutum stems and leaves. (A) The box plot illustrated the degree of dispersion in unigene expression levels across six samples. (B) The volcano plot illustrated the distribution of differentially expressed genes, with screening criteria established at p.adjust < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1. (C) GO term enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in stems and leaves. The horizontal axis represented the proportion of differentially expressed genes associated with each GO term relative to the total number of differentially expressed genes, while the vertical axis indicated the description of the GO function. The color of the dots indicated the p.adjust, and the size of the dots reflected the number of differentially expressed genes. The figure displayed only the top 20 most significant entries from the enrichment results. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes in stems and leaves. The horizontal axis represented the proportion of differentially expressed genes associated with each pathway relative to the total number of differentially expressed genes, while the vertical axis indicated the description of the KEGG pathway function.

To elucidate the biological functions of DEGs, GO annotation and KEGG pathway analysis were performed (Fig. 2C and D, Table S12). GO enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs were significantly associated with DNA-binding transcription factor activity, heme binding, carbohydrate metabolic process, plasma membrane, iron ion binding, and chloroplast pathway (p.adjust < 0.05). Additionally, DEGs were enriched in pathways related to plant-type secondary cell wall biogenesis, cell wall organization, and cellulose biosynthetic process, suggesting their regulatory roles in stem development and metabolite accumulation in S. acutum. KEGG enrichment analysis identified 112 metabolic pathways, with the most significant enrichment in carbon metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, plant hormone signal transduction, and photosynthesis (p.adjust < 0.05) (Table S12). We concentrated on tyrosine metabolism and phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis, which involved 21 and 17 DEGs, respectively. These genes were likely implicated in the synthesis of tyrosine, a precursor for BIAs. Furthermore, we identified 11 DEGs in the isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis pathway, including seven genes involved in the biosynthesis of dopamine, a key precursor in the upstream pathway of BIA synthesis. Among these, two genes were annotated as tyrosine aminotransferases (TyrAT), and five were annotated as polyphenol oxidases (PPO). The remaining genes were associated with the synthesis of other amines and amino acids. We hypothesized that the DEGs may be involved in the biosynthesis of BIAs in S. acutum.

Candidate gene screening for biosynthetic pathway of active compounds in S. acutum

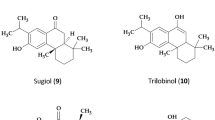

The main active compounds in S. acutum are BIAs, such as sinomenine, corydalmine, and corytuberine2. Given the shared biosynthetic origin of most BIAs in S. acutum, candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis were identified by the blast comparison of unigenes from the transcriptome data with known enzyme genes from other species. Integrating the results of differential metabolites and DEGs in stems and leaves, we hypothesized the involvement of candidate genes in BIA biosynthesis (Figs. 3 and 4, Table S13). Specifically, we screened 53 genes (solid arrow in Fig. 3, Table S13) potentially involved in the known pathway and 60 genes (dotted arrow in Fig. 3, Table S13) associated with the synthesis of downstream BIAs, such as stepharine, sinoacutine, and fangchinoline (Fig. 3). Notably, all enzyme genes in the biosynthetic pathway for (S)-reticuline, a key intermediate in BIA biosynthesis, were screened (light blue pathway in Fig. 3). This indicated that S. acutum, like other BIA-producing species such as P. somniferum and Corydalis yanhusuo, utilized a common pathway to produce (S)-reticuline, laying the groundwork for downstream BIAs biosynthesis22. Although no candidate genes were identified in the morphine pathway (dark blue pathway in Fig. 3), consistent with the absence of relevant BIAs in the metabolomic data, other skeletal types of BIAs were detected, including stephaarine (pink pathway), fangchinoline (green pathway), artabotrine and menisperine (yellow pathway), and 8-oxyberberine (purple pathway). In conjunction with the structures of these compounds, we hypothesize that candidate genes, including CYP450, methyltransferases (MTs), 2-ODDs, and reductases, such as short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs) and aldo-keto reductases (AKRs), might play a role in BIA biosynthesis (Fig. 3). To narrow down the candidate genes, we analyzed their expression levels in different tissues using a gene expression heatmap (Fig. 4, Table S14). The heatmap revealed tissue-specific regulation of gene expression, providing a framework for correlating gene expression with metabolite accumulation and screening candidate genes such as CYP450, methyltransferase and reductase.

Putative BIA biosynthetic pathways and candidate genes in S. acutum. A total of 139 unigenes were implicated in BIA biosynthesis via blastn homology. The red numbers indicate candidate gene counts per enzyme. The solid arrows denote experimentally validated reactions in Menispermaceae or Papaveraceae family; dashed arrows represent uncharacterized steps. Abbreviations: TyrAT tyrosine aminotransferase, TyDC tyrosine/dopa decarboxylase, PPO, polyphenol oxidase, NCS norcoclaurine synthase, 6OMT (S)-norcoclaurine 6-O-methyltransferase, CYP80B (S)-N-methylcoclaurine 3ʹ-hydroxylase, CNMT (S)-coclaurine N-methyltransferase, 4ʹOMT (S)-3ʹ-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4ʹ-O-methyltransferase, BBE berberine bridge enzyme, SOMT scoulerine 9-O-methyltransferase.

Screening and phylogenetic analysis of candidate CYP450 genes downstream of sinomenine biosynthesis

Sinomenine, the principal active constituent of S. acutum, belongs to the morphinan alkaloids. Current research has predominantly focused on the upstream biosynthetic steps of sinomenine, as it shares a common pathway with most BIAs, producing the key intermediate (S)-reticuline. An et al. identified MdCYP80G10 from M. dauricum, the only functional gene reported to catalyze the conversion of (S)-reticuline to sinoacutine, a key compound in the synthesis of the sinomenine skeleton16. In the transcriptome data of S. acutum, we found only one unigene 9141 annotated as CYP80G, which showed no significant differential expression across tissues. To comprehensively screened CYP450 genes involved in sinoacutine synthesis, we expanded our screening range. After excluding genes with short sequences or incomplete coding regions, a total of 105 CYP450 genes were screened. These genes were classified into seven CYP450 clans based on phylogenetic clustering with functional CYP450s from diverse families across species (Fig. 5, Table S15). CYP450s involved in BIA biosynthesis primarily belong to the CYP80, CYP82, CYP719 families of the CYP71 clan10. Through functional annotation and phylogenetic analysis, 12 CYP450 genes from these key families were identified (highlighted in red in Fig. 5). Heatmap analysis of their expression in different tissues (Fig. 4, Table S14) revealed that three genes exhibited high expression levels in stems (highlighted in red in Fig. 4). Based on phylogenetic analysis and differential metabolite expression, we hypothesize that these three highly expressed CYP450s, along with unigene 9141 annotated as CYP80G, are promising candidates for further investigation in the biosynthesis of the sinomenine skeleton.

Phylogenetic analysis of candidate CYP450s from S. acutum. CYP450s for clustering include 105 unigenes screened from S. acutum and 123 functionally identified genes from various species. The green dots represent CYP450 genes that were screened from the transcriptome data based on annotation information. The unigenes highlighted in red indicated the screened genes belonging to the CYP80, CYP82, and CYP719 families. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7 software, with 1,000 bootstrap iterations performed to assess node support. The amino acid sequence information is available in Supplemental Table S15.

Screening of downstream candidate reductase genes for sinomenine biosynthesis

Combined with the structural formula of sinomenine, we hypothesize that the transformation from (S)-reticuline to sinomenine involves CYP450-mediated oxidation to produce sinoacutine, followed by catalytic actions involving reductases, 2-ODDs and O-MTs. The conversion of sinoacutine to sinomenine requires the reduction of the C7 ketone group to a hydroxyl group, likely catalyzed by reductases. Drawing parallels from the morphine biosynthetic pathway, we hypothesize that SDRs and AKRs are involved in this process23. The SDR superfamily, one of the largest enzyme families, is ubiquitous across all living organisms24. Despite low sequence identity, SDRs share conserved features, including a Rossmann-fold structure, a cofactor binding site (TGxxxGxG), and a catalytic domain fragment (NSYK)25. Three SDRs have been identified in the BIAs biosynthetic pathway, including SalR26, SanR27, and NOS28. In contrast, AKRs are characterized by a triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel structure with a conserved folded peptide backbone of alternating α-helices and β-chains29. Although AKRs and SDRs have distinct tertiary structures, their catalytic tetrad residues (tyrosine and lysine) overlap. Notably, two AKRs, DRR and COR, play significant roles in BIA metabolism and exhibit high homology30,31.

After annotating the transcriptome data and excluding short sequences or incomplete transcripts, 20 reductase genes were screened. Phylogenetic analysis of these genes, compared with functional reductase genes from other species (Fig. 6, Table S15), revealed that most belonged to the SDR family, while only two genes were classified as AKR. Heatmap analysis of their expression in different tissues revealed that 10 genes were highly expressed in leaves, while the other 10 genes were more prominent in stems (highlighted in red in Fig. 4, Table S14). Notably, all 10 stem-enriched genes belonged to the SDR family. Combined with phylogenetic analysis, differential gene expression, and metabolite profiling, we hypothesize that these 10 SDRs key candidates for involvement in sinomenine biosynthesis.

Phylogenetic analysis of candidate reductases from S. acutum. The reductases screened in S. acutum were denoted by green circles and red squares. A total of 20 reductases from S. acutum and 18 functional reductases from different species were selected for phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7 software, with 1000 bootstrap iterations performed to evaluate node support. Amino acid sequence information is provided in Supplemental Table S15.

Screening of downstream candidate 2-ODDs for sinomenine biosynthesis

We hypothesize that demethylation at the C6 site to form a C6 ketone is essential for the conversion of sinomenine. This process likely requires the involvement of 2-ODDs, a key enzyme family in the morphinan biosynthetic pathway. The 2-ODDs superfamily, the second-largest enzyme family in plant genomes, primarily facilitates oxygenation/hydroxylation reactions32. These enzymes use iron as a cofactor and 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) as a cosubstrate10. Based on amino acid sequence similarity, 2-ODDs are classified into three classes, DOXA, DOXB, and DOXC. The DOXC class is widely implicated in the metabolism of phytochemicals, including phytohormones and flavonoids32. Four 2-ODDs from P. somniferum have been identified in the BIA biosynthetic pathway, including 6-O-demethylase (T6ODM), codeine O-demethylase (CODM), protopine O-dealkylase (PODA), and papaverine 7-O-demethylase (P7ODM), where they catalyze O-demethylations or O, O-demethylenations33,34,35.

From the transcriptome data, seven 2-ODD genes were screened after excluding short or incomplete sequences. Phylogenetic analysis of these genes, compared with functional 2-ODDs from other species (Fig. 7, Table S15), revealed that they clustered into six branches of the DOXC class: DOXC13, DOXC15, DOXC22, DOXC52, DOXC31, and DOXC4132. Notably, genes in the DOXC52 branch are predominantly associated with BIA biosynthesis10, suggesting that unigene11331 and unigene7147 are promising candidates for further research. Heatmap analysis of their expression in different tissues (Fig. 4, Table S14) showed that three genes were highly expressed in leaves, including unigene11331 and unigene7147, while four genes were more prominent in stems (highlighted in red in Fig. 4). Integrating phylogenetic analysis, differential gene expression, and metabolite profiling, we hypothesize that these four stem-enriched 2-ODDs, along with unigene11331 and unigene7147, may play a role in sinomenine biosynthesis and warrant further investigation.

Phylogenetic analysis of candidate 2-ODDs from S. acutum. The 2-ODDs screened in S. acutum were indicated by red circles. A total of seven 2-ODDs screened in S. acutum and 91 functional genes of 2-ODDs from different species were selected for phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7 software, with 1000 bootstrap iterations performed to evaluate node support. Amino acid sequence information is provided in Supplemental Table S15.

Screening of downstream candidate O-MTs for sinomenine biosynthesis

Based on the structural characteristics of sinomenine, we hypothesize that the final biosynthetic step involves O-MTs-mediated methylation of the C7-hydroxyl group to form a methoxy moiety. Methyltransferases typically utilize S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor for modifying natural products36. Methyltransferases are classified based on their target atoms into O-MTs, C-methyltransferase (C-MTs), N-methyltransferase (N-MTs), S-methyltransferase (S-MTs), and specialized enzymes such as inorganic arsenic methyltransferase (Cyt19). O-MTs are characterized by iterative α-helices and β-strands, along with conserved C-terminal motifs37, including glycine-rich SAM-binding domains, metal-binding sites, and dimerization domains38. Over 10 O-MTs have been functionally characterized in the BIAs biosynthetic pathway of species such as P. somniferum and Coptis japonica, including 6OMT, 4’OMT, N7OMT, 7OMT, SOMT, OMT2, which catalyze key methylation reactions10. These enzymes exhibit catalytic promiscuity, enabling methylation at common hydroxyl sites in 1-BIA and protoberberine compounds, which possess relatively simple skeletal structures39.

By integrating transcriptome annotation data and excluding short or incomplete sequences, we identified 35 putative O-MTs in S. acutum. Phylogenetic analysis of these sequences, alongside functionally characterized O-MTs and N-MTs from other species (Fig. 8, Table S15), revealed a clear distinction between O-MTs and N-MTs. Nine genes (highlighted in pink in Fig. 8) clustered with known BIA biosynthetic O-MTs, suggesting their potential involvement in BIA biosynthesis. Heatmap analysis of 35 O-MTs genes in different tissues (Fig. 4, Table S14) indicated that 21 genes were highly expressed in leaves, while 14 genes exhibited elevated expression in stems (highlighted in red in Fig. 4). Integrating phylogenetic analysis, differential gene expression, and metabolite profiling data, we hypothesize that the 14 stem-enriched O-MTs, particularly unigene9784, may play a critical role in the final methylation step of sinomenine biosynthesis.

Phylogenetic analysis of candidate O-MTs from S. acutum. The O-MTs screened in S. acutum were represented by soil-green diamonds. A total of 35 O-MTs in S. acutum and 95 functional genes of O-MTs from different species were selected for phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7 software, with 1000 bootstrap iterations performed to evaluate node support. Amino acid sequence information is provided in Supplemental Table S15.

Discussion

The mining of candidate genes involved in the BIAs biosynthetic pathway from S. acutum is pivotal for understanding its medicinal properties and provides critical insights into the biosynthetic pathways of active components such as sinomenine and fangchinoline, with implications for their heterologous synthesis. In this study, we focused on perennial wild S. acutum specimens and sequenced the transcriptome of its stems and leaves. After removing redundant and similar sequences, we identified 71,003 unigenes, significantly enriching existing omics data for S. acutum. Integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses across tissues enabled the identification of 113 candidate genes potentially involved in BIA biosynthesis. Notably, we proposed a putative biosynthetic pathway for the clinically significant compound sinomenine and prioritized four CYP450s, 10 reductases, six 2-ODDs, and 14 O-MTs through comparative omics and phylogenetic analysis. These candidate establish foundation for elucidating biosynthetic pathways, validating gene functions, and enabling synthetic biology applications for sinomenine production.

To align with conservation ethics, this study focused on stems and leaves of S. acutum to avoid damaging perennial root systems. Metabolomic profiling revealed isoquinoline alkaloids as the dominant class (118 metabolites; 40% of total alkaloids), with 69 showing significant tissue-specific differences and stem-enriched accumulation. Yang et al.1 similarly reported higher BIA content in stems versus leaves, corroborating our findings. Transcriptomic analysis revealed stem-biased expression patterns for most DEGs, while a subset of candidate genes exhibited preferential expression in leaves, a phenomenon corroborated by prior studies1. Potential regulatory complexities, including negative feedback mechanisms, warrant further investigation. Functional characterization of candidate genes will be pursued in future work.

Metabolite profiling identified structurally diverse BIAs in S. acutum, including 1-benzylisoquinoline alkaloid (S)-norcoclaurine, aporphine alkaloid magnoflorine, morphinan alkaloid sinomenine, protoberberine alkaloid tetrahydropalmatrubine, and bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloid fangchinoline (Fig. 3). This chemical diversity underpins S. acutum’s pharmacological efficacy, motivating intensified research on its biosynthetic machinery. By integrating metabolite structures with cross-species enzyme homology, we identified 53 genes potentially involved in established pathways and 60 candidates for novel BIA modifications, highlighting unexplored biosynthetic complexity.

Special emphasis was placed on sinomenine biosynthesis due to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties40. Drawing parallels to morphine biosynthesis, we hypothesized shared enzymatic logic, particularly CYP450-mediated reactions critical to morphinan scaffold formation. CYP450 was an important oxidase in the sinomenine biosynthesis, participating not only in upstream hydroxylation reactions41, but also being identified in M. dauricum as involved in the synthesis of the sinomenine skeleton16. CYP450s, implicated in hydroxylation, isomerization, and coupling reactions, are classified into CYP80, CYP82, and CYP719 families10. For instance, CYP719B1 (SalSyn) catalyzes salutaridine synthesis via C-C phenol coupling in morphine biosynthesis42, while CYP80 homologs mediate sinoacutine formation16. Through phylogenetic filtering, we prioritized four CYP450 candidates for further investigation. Key oxidative modifications (e.g., C6 demethylation and C7 keto-methoxy interconversion) likely involve 2-ODDs, as evidenced by T6ODM/CODM homologs in opium poppy33. Expanding screening to flavin-dependent oxidoreductases (FADOXs) may further resolve pathway gaps10. Comparative omics and phylogenetic analyses to significantly narrow the selection of candidate genes from transcriptomic data. For example, when screening for genes involved in the final methylation reaction of the sinomenine biosynthesis pathway, we refined the initial pool of 35 O-MTs down to 14 promising candidates. This method streamlines future gene function verification efforts and provides an important framework for studying the biosynthesis pathway of sinomenine.

Future work will employ genomic sequencing, isotope tracer studies, and enzyme engineering to resolve BIA biosynthetic networks in S. acutum. Our work will contribute to the identification of functional genes in S. acutum and provide a reference for the study of biosynthetic pathways and gene screening of active ingredients in other medicinal plants.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and chemicals

S. acutum specimens were collected from Luoyang City, Henan Province, China (33°42’N, 111°45’E) and identified by Dr. Lian Conglong. To preserve the wild plant resources of S. acutum, only stems and leaves from perennial plants were harvested. Fresh tissues were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C for downstream analyses. Standards (S)-reticuline, sinoacutine, and sinomenine were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), with the purity of ≥ 95%. HPLC-grade methanol, LC/MS-grade acetonitrile, formic acid, and ethyl acetate were procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

RNA extraction and sequencing library construction

Total RNA was isolated from stem and leaf tissues using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA), with three biological replicates per tissue type43. RNA integrity was verified via1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and purity (A260/A280 = 1.8–2.1) was quantified using a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). High-quality RNA was used to construct cDNA libraries with the MGIEasy RNA Library Prep Kit for BGI®, involving poly(A)+ mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, and strand-specific cDNA synthesis. The entire process was entrusted to Wuhan Bena Technology Co., Ltd. After the library test was qualified, the BGI DNBSEQ-T7 high-throughput sequencing platform was used for sequencing.

Quality control and functional annotation

Raw data obtained underwent filtration to exclude reads containing more than 5% N-base content, reads with low-quality base counts exceeding 50%, and reads containing adapter contamination and repetitive sequences resulting from PCR amplification. Subsequently, homology search, protein domain identification (PFAM), protein signal prediction (SingalP), and comparison with existing annotation databases (GO, KEGG, KOG, NR, PATHWAY, Pfam, Uniprot) were employed to annotate the transcriptome function.

Targeted alkaloid profiling in S. acutum tissues

A qualitative and quantitative method was employed to detect the alkaloids in S. acutum44. Three biological replicates of stems and leaves from S. acutum, totaling six samples, underwent metabolomic analysis. The samples were freeze-dried under vacuum and subsequently ground to a fine powder using a grinder (MM 400, Retsch). 50 mg of the powdered sample were combined with 1,200 µL of pre-cooled 70% methanol water and subjected to vortex for 30 s every 30 min over a total of 6 cycles. Following centrifugation at 11,000 rpm for 3 min, the supernatant was collected, and the sample was filtered through the 0.22 μm microporous membrane and stored in an injection bottle for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. The instrumental system utilized for data acquisition primarily comprised ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) (ExionLC™ AD, Sciex) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS, TripleTOF6600, AB Sciex). The Agilent SB-C18 column (80 Å, 1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Agilent) from Agilent was selected. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C, with an injection volume of 2 µL and a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The elution gradient proceeded as follows: 0 ~ 9 min, 5%~95% B; 9 ~ 10 min, 95% B; 10 ~ 11 min, 95%~5% B; 11 ~ 14 min, 5% B.

The mass spectrometry conditions were as follows: electrospray ionization (ESI) temperature set to 550 °C, ion spray voltage (IS) at 1,500 V (positive ion mode) /-1,500 V (negative ion mode), with the ion source gases I (GSI), gas II (GSII), and curtain gas (CUR) maintained at 50, 60 and 25 psi, respectively. The collision-induced ionization parameters were configured to high, while the QQQ scan was performed in MRM mode, and the collision gas (nitrogen) was adjusted to medium. By further optimizing the declustering potential (DP) and collision energy (CE), the DP and CE of each MRM ion pair were finalized. Please refer to the Supporting Information for a more detailed qualitative and quantitative analysis.

UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis of key intermediates

UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis was conducted for the key intermediates (S)-reticuline, sinoacutine, and sinomenine in the biosynthetic pathway of sinomenine. The sample extraction procedure follows the steps outlined in the aforementioned method, with the only modification being an increase in the sample powder weight to 100 mg. The chromatographic utilized Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (100 Å, 1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters) with a mobile phase of 0.1% formic acid water (A) and acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The injection volume was 1 µL, and the column temperature was maintained at 30℃. The gradient elution program proceeded as follows: 0–8 min, 95%~70% B; 8–13 min, 70%~35% B; 13–14 min, 35%~10% B; 14–15 min, 10%~95% B; 15–17 min, 95% B. The mass spectrometry conditions included an ESI ion source operating in positive ionization mode, with a capillary voltage of 300 KV, 100 °C, desolvation gas temperature of 500 °C, desolvation gas flow rate of 800 L/h, cone gas flow rate of 50 L/h, collision voltage of 6 eV, collision energy of 20–30 eV, and a scan range of 50 − 1,500 m/z.

Differential gene expression analysis

Differential expression analysis was performed using the read count data of unigene expression from each sample, obtained through expression quantification. DESeq2 software (https://bioconductor.org/packages/DESeq2/) was employed for differential expression analysis45, a filtering experimental data with a threshold of p.adjust < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1. Volcano plots were used to visually represent the relationship between unigene expression levels, log2FoldChange differences, and p.adjust values across the samples. ClusterProfiler software (https://bioconductor.org/packages/ClusterProfiler/) was employed to identify GO terms or KEGG Pathways in which differentially expressed genes showed significant enrichment compared to all annotated genes. The significance of enrichment was indicated by the proximity of the p.adjust value to zero. The top 20 most significant enrichments were plotted.

Candidate gene screening for BIA biosynthesis

According to the transcriptome annotation and differential gene expression analysis, combined with the structure characteristics of sinomenine compounds, the biosynthetic pathway of sinomenine was analyzed, and potential candidate genes were speculated. TBtools46 software (https://github.com/CJ-Chen/TBtools) facilitated the construction of a relative expression heatmap for genes across different tissues of S. acutum, revealing distinct expression patterns. Additionally, using MEGA 747 software (http://www.megasoftware.net/mega.php), a phylogenetic was constructed employing the neighbour-joining method to compare candidate genes with identified functional genes, and sequence homology among the genes was evaluated. Candidate genes were further selected based on the relative accumulation of metabolites in different tissues.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI/SRA database (Accession number PRJNA1206784).

References

Yang, Y. et al. Full-length transcriptome and metabolite analysis reveal reticuline epimerase-independent pathways for benzylisoquinoline alkaloids biosynthesis in Sinomenium acutum. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1086335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1086335 (2022).

Lyu, H. N. et al. Alkaloids from the stems and rhizomes of Sinomenium acutum from the Qinling Mountains, China. Phytochemistry 156, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.09.009 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Identification and quality control strategy of impurities in Zhengqing Fengtongning injection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 219, 114970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114970 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Multifunctional nanoparticles of sinomenine hydrochloride for treat-to-target therapy of rheumatoid arthritis via modulation of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Controlled Release 348, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.05.016 (2022).

Kashiwada, Y. et al. Anti-HIV benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and flavonoids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera, and structure-activity correlations with related alkaloids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 443–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.020 (2005).

Gorpenchenko, T. Y., Grigorchuk, V. P., Bulgakov, D. V., Tchernoded, G. K. & Bulgakov, V. P. Tempo-spatial pattern of Stepharine accumulation in Stephania glabra morphogenic tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040808 (2019).

Xu, T. et al. A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Pharmacol. Res. 152, 104632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104632 (2020). Magnoflorine.

Dai, W. L. et al. Selective blockade of spinal D2DR by levo-corydalmine attenuates morphine tolerance via suppressing PI3K/Akt-MAPK signaling in a MOR-dependent manner. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0175-1 (2018).

Li, J. et al. The phytochemical scoulerine inhibits aurora kinase activity to induce mitotic and cytokinetic defects. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2312–2320. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00429 (2021).

Dastmalchi, M., Park, M. R., Morris, J. S. & Facchini, P. Family portraits: The enzymes behind benzylisoquinoline alkaloid diversity. Phytochem. Rev. 17, 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-017-9519-z (2018).

Liscombe, D., MacLeod, B., Loukanina, N., Nandi, O. & Facchini, P. Evidence for the monophyletic evolution of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in angiosperms. Phytochemistry 66, 2501–2520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.044 (2005).

Facchini, P. & Park, S. Developmental and inducible accumulation of gene transcripts involved in alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy. Phytochemistry 64, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00292-9 (2003).

Huang, F. & Kutchan, T. Distribution of morphinan and benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid gene transcript accumulation in Papaver somninferum. Phytochemistry 53, 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00600-7 (2000).

Ziegler, J., Diaz-Chávez, M., Kramell, R., Ammer, C. & Kutchan, T. J. P. Comparative macroarray analysis of morphine containing Papaver somniferum and eight morphine free Papaver species identifies an O-methyltransferase involved in benzylisoquinoline biosynthesis. 222, 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-005-1550-4 (2005).

Li, Y., Winzer, T., He, Z. & Graham, I. A. Over 100 million years of enzyme evolution underpinning the production of morphine in the Papaveraceae family of flowering plants. Plant. Commun. 1, 100029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100029 (2020).

An, Z. et al. Lineage-specific CYP80 expansion and benzylisoquinoline alkaloid diversity in early-diverging eudicots. Adv. Sci. e2309990. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202309990 (2024).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 323. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Xu, D. et al. Integration of full-length transcriptomics and targeted metabolomics to identify benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthetic genes in Corydalis yanhusuo. Hortic. Res. 8, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-00450-6 (2021).

Dastmalchi, M. et al. Neopinone isomerase is involved in codeine and morphine biosynthesis in opium poppy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-019-0247-0 (2019).

Persson, B. et al. The SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase and related enzymes) nomenclature initiative. Chem. Biol. Interact. 178, 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.040 (2009).

Kallberg, Y. & Persson, B. Prediction of coenzyme specificity in dehydrogenases/reductases. A hidden Markov model-based method and its application on complete genomes. FEBS J. 273, 1177–1184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05153.x (2006).

Ziegler, J. et al. Comparative transcript and alkaloid profiling in Papaver species identifies a short chain dehydrogenase/reductase involved in morphine biosynthesis. Plant J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 48, 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02860.x (2006).

Kavanagh, K. L., Jörnvall, H., Persson, B. & Oppermann, U. Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families: The SDR superfamily: Functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3895–3906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-008-8588-y (2008).

Chen, X. & Facchini, P. J. Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase catalyzing the final step of noscapine biosynthesis is localized to laticifers in opium poppy. Plant J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 77, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12379 (2014).

Penning, T. M. The aldo-keto reductases (AKRs): Overview. Chem. Biol. Interact. 234, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2014.09.024 (2015).

Farrow, S. C., Hagel, J. M., Beaudoin, G. A., Burns, D. C. & Facchini, P. J. Stereochemical inversion of (S)-reticuline by a cytochrome P450 fusion in opium poppy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 728–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1879 (2015).

Unterlinner, B., Lenz, R. & Kutchan, T. M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of codeinone reductase: The penultimate enzyme in morphine biosynthesis in the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. Plant J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 18, 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00470.x (1999).

Kawai, Y., Ono, E. & Mizutani, M. Evolution and diversity of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily in plants. Plant J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 78, 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12479 (2014).

Hagel, J. M. & Facchini, P. J. Dioxygenases catalyze the O-demethylation steps of morphine biosynthesis in opium poppy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 273–275. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.317 (2010).

Hagel, J. M. et al. Transcriptome analysis of 20 taxonomically related benzylisoquinoline alkaloid-producing plants. BMC Plant Biol. 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0596-0 (2015).

Farrow, S. C. & Facchini, P. J. Dioxygenases catalyze O-demethylation and O,O-demethylenation with widespread roles in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid metabolism in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28997–29012. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.488585 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. An Arabidopsis thaliana methyltransferase capable of methylating farnesoic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 448, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2005.08.006 (2006).

Kagan, R. M. & Clarke, S. Widespread occurrence of three sequence motifs in diverse S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases suggests a common structure for these enzymes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 310, 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.1994.1187 (1994).

Ibrahim, R. K., Bruneau, A. & Bantignies, B. Plant O-methyltransferases: Molecular analysis, common signature and classification. Plant Mol. Biol. 36, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005939803300 (1998).

Bu, J. et al. Catalytic promiscuity of O-methyltransferases from Corydalis yanhusuo leading to the structural diversity of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Hortic. Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhac152 (2022).

Li, J. M. et al. Pharmacological mechanisms of sinomenine in anti-inflammatory immunity and osteoprotection in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharmacol. 121, 155114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155114 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Functional characterization of (S)–N-methylcoclaurine 3′-hydroxylase (NMCH) involved in the biosynthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in Corydalis yanhusuo. 168, 507–515 (2021).

Gesell, A. et al. CYP719B1 is salutaridine synthase, the C-C phenol-coupling enzyme of morphine biosynthesis in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24432–24442. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.033373 (2009).

Lian, C. et al. Multi-omics analysis of small RNA, transcriptome, and degradome to identify putative miRNAs linked to MeJA regulated and oridonin biosynthesis in Isodon rubescens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 258, 129123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.129123 (2024).

Zhu, G. et al. Rewiring of the fruit metabolome in tomato breeding. Cell 172, 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.019 (2018).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of Fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: An integrative Toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 (2020).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304650). Key project at central government level: The ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiment: CL.L. and SQ.C. Performed the experiments: XY.L. Analyzed the data: JC.C., R.M., Y.M., and L.Z. Wrote the manuscript: XY.L. Helped in data analysis and manuscript preparation: CL.L, Y.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We ensured compliance with relevant guidelines for the collection of plant specimens in our field studies, adhering to the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Additionally, we confirm that our research does not involve any studies with human or animal subjects.

Material availability

S. acutum was collected from Luoyang City, Henan Province. We have determined that S. acutum is not a protected plant in China. To promote the sustainable development of plant resources, we collected only the above-ground portions of the plant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Chen, J., Ma, R. et al. Metabolic profiling and transcriptome analysis of Sinomenium acutum provide insights into the biosynthesis of structurally diverse benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Sci Rep 15, 5877 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90334-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90334-3