Abstract

In the field of multi-organ 3D medical image segmentation, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are limited to extracting local feature information, while Transformer-based architectures suffer from high computational complexity and inadequate extraction of spatial and channel layer information. Moreover, the large number and varying sizes of organs to be segmented result in suboptimal model robustness and segmentation outcomes. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a novel network architecture, DS-UNETR++, specifically designed for 3D medical image segmentation. The proposed network features a dual-branch feature encoding mechanism that categorizes images into coarse-grained and fine-grained types before processing them through the encoding blocks. Each encoding block comprises a downsampling layer and a Gated Shared Weighted Pairwise Attention (G-SWPA) submodule, which dynamically adjusts the influence of spatial and channel attention on feature extraction. Additionally, a Gated Dual-Scale Cross-Attention Module (G-DSCAM) is incorporated at the bottleneck stage. This module employs dimensionality reduction techniques to cross-coarse-grained and fine-grained features, using a gating mechanism to dynamically balance the ratio of these two types of feature information, thereby achieving effective multi-scale feature fusion. Finally, comprehensive evaluations were conducted on four public medical datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that DS-UNETR++ achieves good segmentation performance, highlighting the effectiveness and significance of the proposed method and offering new insights for various organ segmentation tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the survey report by Sabina Umirzakova’s team1, in the domain of medical image analysis, achieving high-precision image restoration remains a significant challenge. Image segmentation, in particular, is a critical and highly challenging research direction that holds substantial practical application value. This includes tumor image segmentation, heart image segmentation, abdominal multi-organ image segmentation, etc. In today’s rapidly advancing computer technology era, harnessing the power of image segmentation to assist physicians in diagnosis not only enhances diagnostic speed but also augments the accuracy of diagnostic outcomes.

With the continuous advancement of modern computing power, deep learning is constantly evolving and innovating, particularly in the field of image segmentation where deep convolutional neural networks (CNN) have found widespread applications. Medical image segmentation is no exception to this trend. Since the introduction of U-Net2, numerous models based on its enhancements have emerged. This can be attributed primarily to the typical encoder-decoder structure and skip connections in U-Net2, which facilitate the propagation of fine-grained information and prevent information loss, thereby enhancing the accuracy of model segmentation. Building upon these advantages, several models have been developed including AFFU-Net3, OAU-Net4, ISTD-UNet5, MultiResU-Net6, SAU-Net7, KiU-Net8, and UCR-Net9. However, due to inherent limitations within CNN itself such as convolutional kernel sizes and strides settings, it can only capture local features in input data and cannot directly establish long-range dependencies for global information processing. To address this issue, researchers have proposed improved network structures and methods like CAT10 with a cross-attention mechanism and LMISA11 enhanced based on gradient magnitude to enhance CNN models’ ability to capture global information. Nevertheless, when it comes to handling volumetric medical images specifically, ineffective establishment of long-range dependencies continues to hinder CNN’s development in volumetric medical image processing.

With the successful application of the Transformer12 architecture in the image domain by Visual Transformer (VIT)13, which replaces convolution operations in CNN with self-attention mechanisms, models are now capable of establishing long-range dependencies between pixels globally. This enables a more effective capture of global information in images. Consequently, there has been an increasing number of researchers exploring segmentation models based on the Transformer architecture. For instance, RT-UNet14 introduces a Skip-Transformer that utilizes a multi-head self-attention mechanism to mitigate the impact of shallow features on overall network performance. SWTRU15 proposes a star-shaped window self-attention mechanism that expands the attention region further to achieve a global attention effect while maintaining computational efficiency. Zhu Zhiqin et al.16 introduced a multi-modal spatial information enhancement and boundary shape correction method, thereby developing an end-to-end brain tumor segmentation model. This model consists of three essential components: information extraction, spatial information enhancement, and boundary shape correction. Furthermore, the LMIS17 framework features a streamlined core feature extraction network and establishes a multi-scale feature interactive guidance architecture. CFNet18 presents the CFF method, which balances spatial-level effectiveness by calculating multi-view features and optimizing semantic gap between shallow and deep features. DFTNet19 designs a dual-path feature exploration network that incorporates both shallow and deep features using a sliding window approach to access deeper information. SDV-TUNet20 introduces an advanced sparse dynamic volume TransUNet architecture, integrating Sparse Dynamic (SD) and Multi-Level Edge Feature Fusion (MEFF) modules to achieve precise segmentation. Zhu Zhiqin’s team21 proposed a brain tumor segmentation method that leverages deep semantic and edge information from multimodal MRI. This approach incorporates a Multi-Feature Inference Block (MFIB), which utilizes graph convolution for efficient feature inference and fusion. Additionally, there exist hybrid image segmentation techniques such as UNETR22, which transform 3D medical images into a sequence and convert the segmentation task into a sequence prediction problem. It leverages the Transformer12 architecture to acquire multi-scale global information and employs a U-shaped network with encoder and decoder for pixel-level prediction. UNETR++23 introduces an efficient Enhanced Pairwise Attention (EPA) block comprising spatial attention modules and channel attention modules. In contrast to CBAM24, where these modules are concatenated, UNETR++23 processes them in parallel, sharing weights for attention calculations, thereby reducing overall network parameters and significantly decreasing computational complexity while maintaining exceptional model performance.

However, current hybrid image segmentation methods still possess certain limitations. Firstly, in the context of multi-scale image fusion, relying solely on convolution operations for local feature extraction may result in the loss of global information. Additionally, convolutions are insensitive to scale variations and thus ineffective in handling objects with different scales, potentially leading to inaccurate segmentation results. Secondly, when it comes to feature extraction based on Transformer12 architectures, the significance of spatial and channel layers is often overlooked. While certain models do incorporate both the spatial and channel dimensions, their utilization remains relatively simple, thus failing to fully leverage the potential of these layers. Moreover, given the diverse types and sizes of numerous organs within the human body, the resulting model may exhibit inadequate robustness, thereby complicating the successful completion of multi-organ segmentation tasks.

To tackle these challenges, this paper presents a 3d medical image segmentation network based on gated attention blocks and dual-scale cross-attention mechanism. Building upon the UNETR++23 architecture, this method introduces a dual-branch feature encoding sub-network that aggregates feature information from both coarse and fine scales. These features are then merged through convolution to capture context-rich spatial information more effectively. To encode feature information, an improved gated shared weighted Paired attention (G-SWPA) block is utilized. Additionally, a gated double-scale cross attention module (G-DSCAM) is designed for the bottleneck part of the network to facilitate dual scale feature fusion of volume images. The performance of DS-UNETR++ is thoroughly evaluated on four public medical datasets. In particular, on the BraTS dataset, HD95 decreased by 0.96 and DSC increased by 0.7% compared to the baseline model, resulting in values of 4.98 and 83.19%, respectively; On the Synapse dataset, HD95 achieved a value of 6.67 while DSC reached 87.75%, representing reductions of 0.86 and improvements of 0.53% compared to the baseline model respectively. These results demonstrate that DS-UNETR++ outperforms other models in terms of segmentation effectiveness as illustrated in Fig. 1 where visual segmentation results closely resemble ground truth labels. The contributions made by this paper can be summarized into three main aspects:

-

(1)

The DS-UNETR++ method is introduced, featuring a dual-branch feature encoding subnetwork. This approach uniquely segments the input image into coarse-grained and fine-grained features during preprocessing, constructing specialized encoding blocks for each scale. In medical imaging, disease or lesion areas exhibit distinct characteristics at varying scales, such as the fine structures at tumor edges and the overall tumor morphology. This design not only captures both macroscopic structures and microscopic details simultaneously but also enhances the model’s capability to detect target features across different scales while preserving spatial continuity and correlation.

-

(2)

Constructing the Gated Shared Weighted Paired Attention (G-SWPA) Block: This design incorporates parallel spatial and channel attention mechanisms, both of which are regulated by a gating mechanism. This allows the model to dynamically adjust the emphasis on spatial versus channel attention based on the characteristics of the input data. For instance, in certain image cases, channel information may be more critical, whereas in others, spatial details may hold greater importance. Consequently, the G-SWPA block enhances the efficiency and quality of feature extraction, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of segmentation outcomes.

-

(3)

Design of a Gated Dual-Scale Cross-Attention Module (G-DSCAM): To address feature fusion at the bottleneck layer, we propose a dimensionality-reduction cross-attention mechanism to perform self-attention calculations. Additionally, a gating mechanism is introduced to dynamically adjust the proportion of two types of feature information. Given that boundary information is typically multi-scale, with different scales collectively determining the accurate placement of segmentation boundaries, this approach enhances sensitivity to detailed features and significantly improves segmentation boundary accuracy.

Related work

This section primarily examines various segmentation methods for medical images. In accordance with the main research focus of this article, it predominantly analyzes image segmentation models based on multi-scale feature extraction. Additionally, it explores diverse attention mechanisms for integrating multi-scale context and provides comparative explanations alongside the model proposed in this article.

Multi scale feature extraction network

The U-Net2 architecture has demonstrated exceptional performance in the field of medical imaging, leading to the emergence of various encoder-decoder network models. These models can be broadly categorized into single-branch and multi-branch encoder networks. Building upon this foundation, many researchers have incorporated multi-scale feature extraction techniques, resulting in further enhancements to the model’s performance.

Single-branch encoder networks are more lightweight, offering enhanced efficiency in both training and inference processes. For instance, V-Net25 leverages multi-scale features to improve model perception and employs the Dice loss function for measuring similarity between predicted segmentation results and ground truth labels. nnUNet26 argues against overly complex model structures that can lead to overfitting, proposing an adaptive architecture capable of extracting features at multiple scales while enhancing model generalization through cross-validation. DeepLab27 utilizes dilated convolution operations to expand the receptive field and introduces spatial pyramid pooling (SPP Layer) for the first time in image segmentation tasks. DeepLabv3+24 incorporates dilated convolutions at different rates for feature map extraction and further integrates local and global features.

Multiple-branch encoders demonstrate enhanced adaptability for segmentation tasks in complex scenes. For instance, DS-TransUnet29 employs dual-scale encoders to extract feature information across different semantic scales and incorporates a Feature Interaction Fusion (TIF) module, effectively establishing global dependency relationships between features of varying scales. DHRNet30 proposes a hybrid reinforcement learning dual-branch network, primarily consisting of a multi-scale feature extraction branch and a global context detail enhancement branch. ESDMR-Net31 utilizes squeeze operations and dual-scale residual connections to design an efficient lightweight network. SBCNet32 introduces both a context encoding module and a boundary enhancement module, employing advanced multi-scale adaptive kernels for tumor identification from two branches. MILU-Net33 designs a dual-path upsampling and multi-scale adaptive detail feature fusion module to minimize information loss. MP-LiTS34 introduces an innovative multi-phase channel-stacked dual-attention module integrated into a multi-scale architecture. BSCNet35 designs a dual-resolution lightweight network capable of capturing top-level low-resolution branch’s multi-scale semantic context.

However, these networks still possess certain limitations. Firstly, the complexity and migration challenges associated with the two-branch encoders designed for these networks remain significant. Secondly, some encoders are only suitable for specific datasets and lack robust generalizability. In contrast, DS-UNETR++ proposed in this paper adopts a simpler and more efficient dual-branch encoder that exhibits wide applicability and can seamlessly integrate as a plug-and-play module within various networks.

Various attention mechanisms in multi-scale context fusion

The Visual Transformer (VIT)13 employs a patch-based approach to divide images into smaller segments and convert them into vectors. By harnessing the self-attention mechanism of the Transformer12 architecture, it achieves a significant improvement in model performance. Consequently, various attention mechanisms have emerged.

Swin-Transformer36 adopts a hierarchical structure, introducing the Swapping Window Multi-head Self-Attention (SW-MSA) mechanism, enabling the model to focus on information at different scales across layers; Swin-Unet37 utilizes Swin Transformer36 as an encoder to extract contextual features and designs a symmetric decoder with patch expanding layers for upsampling operations; VT-Unet38 employs parallel self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms in the decoder to capture fine details for boundary refinement; nnFormer39 combines interleaved convolutions and self-attention operations, introducing local-global volume-based self-attention to learn volumetric representations and designs skip attention mechanisms to replace traditional skip connections; Axial-DeepLab40 proposes axial attention, reducing 2D computations to two 1D computations, significantly lowering computational costs; MedT41 designs a gating position-sensitive axial attention mechanism, introducing multiple learnable parameters to control the amount of information provided to keys, queries, and values; TransUnet42 combines attention-based mechanisms with CNN-based feature maps to recover the original image through multi-layered upsampling; 3D UX-Net43 simulates the W-MSA and SW-MSA architectures from Swin-Transformer36 using convolutional methods and improves model performance with fewer normalization and activation layers. UNETR22 extracts feature maps using Transformers and refines them again with CNNs; Swin-UNETR44 utilizes shift windows for self-attention computation, extracting features at five different resolutions and integrating residual convolution blocks in the decoder stage for feature map fusion and upsampling.

The existing models, however, fail to fully exploit the spatial and channel information due to their oversight. In contrast, this paper proposes an enhanced Gate-shared Weight Pair Attention (G-SWPA) block that specifically focuses on attention computation for both spatial and channel information. It introduces a gate control valve to effectively handle the fusion of these two types of information. The G-SWPA module designed in this study is characterized by its lightweight nature and computational efficiency.

Method

Overall architecture

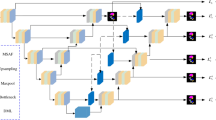

Overall network architecture diagram. A subnetwork for dual-branch feature encoding is designed to extract feature information from two scales simultaneously, effectively capturing target features at different levels. An introduction of a gated shared weighted pairwise attention (G-SWPA) block utilizes a gating mechanism to automatically adjust the influence of spatial and channel attention on feature extraction, resulting in more effective feature information. Finally, a gated dual-scale cross-attention module (G-DSCAM) enhances the effect of feature fusion.

The overall network architecture of DS-UNETR++ is illustrated in Fig. 2, resembling the architecture of UNETR++23. The primary structure of this study maintains a U-shaped design, comprising three main components: encoder, bottleneck, and decoder. Initially, the input medical three-dimensional images are categorized into coarse-grained and fine-grained feature inputs before entering the encoder section. The encoder consists of three stages, each with two branches containing two types of encoding blocks for handling coarse-grained and fine-grained feature inputs. Each type of encoding block comprises a downsampling layer and two consecutive Gate-Shared Weight Pair Attention (G-SWPA) sub-modules. Following the initial encoding in each stage, a Convolutional Fusion module (Conv-Fusion) further consolidates information from both scales of features to capture comprehensive contextual information in adjacent spatial positions. The bottleneck section includes a single stage processed by two types of encoding blocks for coarse-grained and fine-grained feature inputs while introducing the Gate-Dual-Scale Cross Attention Module (G-DSCAM) for processing. In the decoder section, a symmetric structure to the encoder is adopted with three stages, each composed of two consecutive G-SWPA blocks and upsampling layers. To further restore image details and integrate deeper feature information, we adopt skip connection methods similar to U-Net2, followed by carrying out two convolution operations to fully recover image size and obtain segmentation image. The main logical relationship is shown in Fig. 3.

The subsequent sections of this paper primarily demonstrate the processing techniques employed on the Medical Segmentation Decathlon-Heart segmentation dataset. By leveraging the image segmentation process utilized in the Heart dataset, these techniques can be readily extended to handle other datasets.

3D patch partitioning

The input image \(X\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times D\times C}\) to DS-UNETR++ is a three-dimensional image obtained after preprocessing, primarily involving steps such as cropping and resampling, where H, W, D, and C respectively refer to the height, width, depth, and number of channels of the input image.

For the Heart dataset, the three-dimensional patch partition mainly performs projections at two scales: coarse-grained and fine-grained. These are transformed into two different high-dimensional tensors, denoted as high-dimensional tensors \({X}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{(H/{P}_{1}\times W/{P}_{2}\times D/{P}_{3})\times {C}_{1}}\) and \({X}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{(H/{Q}_{1}\times W/{Q}_{2}\times D/{Q}_{3})\times {C}_{1}}\), where \(H/{P}_{1}\times W/{P}_{2}\times D/{P}_{3}\) and \(H/{Q}_{1}\times W/{Q}_{2}\times D/{Q}_{3}\) represent the output shapes of tensors \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) respectively, and \({P}_{1}\backsim {P}_{2}\) and \({Q}_{1}\backsim {Q}_{2}\) denote scaling factors for the different side lengths of the two scales. \({C}_{1}\) represents the sequence length of \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\).It is worth noting that setting the sequence length to be the same facilitates subsequent fusion processing, which enhances efficiency in data integration. For different datasets, fine-tuning of these symbols may be necessary due to variations in specific values according to each dataset’s characteristics. To optimize computational complexity, the three-dimensional patch partition primarily comprises a convolutional layer and a normalization layer. In practice, the convolutional stride in the embedding block will also vary accordingly based on input patch sizes.

Encoder

The encoder is mainly divided into three stages, each consisting of two encoding blocks and one feature fusion block. The two encoding blocks receive high-dimensional tensors \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) of different scales from the three-dimensional patch partition. The downsampling layers inside the encoding blocks are used to capture the hierarchical object characteristics of different scales. Then, through the two gate-shared-weight paired attention (G-SWPA) submodules inside the encoding blocks, long-range dependency relationships between patches are captured. After the two encoding blocks undergo the above operations, the high-dimensional tensors \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) complete the preliminary acquisition of long-range dependency relationships and are entangled with the initial high-dimensional tensors. Then, the high-dimensional tensors \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) are output to the convolution fusion block (Conv-Fusion). The Conv-Fusion block downsamples the feature information of one scale, then concatenates the two kinds of feature information, and finally completes the fusion of the two-scale feature information through two convolution operations, outputting it to the decoder stage.

Three-dimensional dual-scale feature information

The long-term dependence between patches can be captured through various attention mechanisms in single-scale encoders. However, the connection between patches for feature information at a single scale will be weakened to some extent, potentially leading to information loss or blurring and failing to capture information at different scales in the image. When multiple scales of features exist in an image, single-scale extraction may not fully express the content of the image. Moreover, focusing solely on local details during single-scale feature extraction while ignoring global information may result in insufficient understanding of the overall structure, impacting subsequent task performance and potentially causing overfitting.

Therefore, this paper employs a two-branch feature coding subnetwork to compensate for this attenuation, with each branch processing scale-specific feature information to acquire more precise edge and line features. In this study, we propose a dual-branch feature extractor based on G-SWPA for extracting 3D feature information. There are three primary considerations as follows: (1) The two-branch feature coding subnetwork enables simultaneous utilization of multi-scale information, facilitating comprehensive understanding of image content and enhancing the model’s comprehension of both image details and overall structure. Specifically, two adjacent patches under a fine-grained feature projection will be in one patch in a coarse-grained feature projection. After the subsequent fusion processing of the two scales of feature information, the effect of feature extraction can be further improved. (2) By utilizing the dual-branch coding subnetwork for separate scale-based projections and coding processes, more accurate segmentation targets can be obtained, leading to improved detection of edges and contours within images. (3) Single-branch image segmentation may result in semantic information loss when dealing with complex scenes or small targets; however, employing a dual-branch approach can mitigate such issues while enhancing segmentation accuracy and robustness. Specifically, this paper uses two relatively independent branch sub-networks for feature extraction. Taking the Heart dataset as an example, the convolutional kernel sizes are \({S}_{1}=({P}_{1},{P}_{2},{P}_{3})\)(primary) and \({S}_{2}=({Q}_{1},{Q}_{2},{Q}_{3})\) (complementary). In the three stages of the encoder, the fine-grained branch obtains outputs with resolutions \(H/{P}_{1}\times W/{P}_{2}\times D/{P}_{3}\), \(H/{2P}_{1}\times W/2{P}_{2}\times D/{2P}_{3}\) and \(H/4{P}_{1}\times W/{4P}_{2}\times D/4{P}_{3}\), while the coarse-grained branch obtains outputs with resolutions \(H/{Q}_{1}\times W/{Q}_{2}\times D/{Q}_{3}\), \(H/2{Q}_{1}\times W/2{Q}_{2}\times D/{2Q}_{3}\) and \(H/4{Q}_{1}\times W/4{Q}_{2}\times D/4{Q}_{3}\).

Gated shared weighted paired attention blocks (G-SWPA)

The improved Gated Shared Weighted Paired Attention Block (G-SWPA) is a module comprising parallel spatial attention and channel attention, controlled by a gating mechanism. In contrast to the EPA module of UNETR++23, this paper introduces gated valves in the output stage of both spatial attention and channel attention. These gated valves automatically adjust the impact of spatial attention and channel attention on feature extraction, assigning greater weight to the party that facilitates feature extraction, and vice versa. Furthermore, this paper adopts the shared weights setting from the EPA23 module. For spatial attention and channel attention, identical key and query parameters are employed while different value parameters are used. This configuration not only reduces parameter count but also enables effective communication through shared weights for obtaining more efficient feature information.

The specific architecture of G-SWPA is illustrated in Fig. 4. This paper exemplifies one of the two types of coding blocks. Initially, the G-SWPA module receives feature map \(X\) and subsequently feeds it into the channel and spatial attention module of the G-SWPA block. The weights for both attention modules \(Q\) and \(K\) are shared; but different \(V\) values are used. Based on this premise, the calculation process for the two attention modules is as follows:

Where \({\widehat{X}}_{s}\) and \({\widehat{X}}_{c}\) represent spatial and channel attention graphs, respectively. \(SAM\) and \(CAM\) represent space attention module and channel attention module respectively. \({Q}_{SW}\) and \({K}_{SW}\) represent matrices of shared queries and shared keys, respectively, and \({V}_{Spatial}\) and \({V}_{Channel}\) represent matrices of spatial value layers and channel value layers, respectively. \({G}_{SA}\) indicates the gating parameter for space attention, and \({G}_{CA}\) indicates the gating parameter for channel attention.

It is worth noting that the EPA23 module effectively employs parallel processing of spatial attention and channel attention, utilizing shared parameters to significantly reduce parameter count. However, in the output stage of this module, the results of spatial attention and channel attention are not weighted but rather added and merged together. This operational approach hinders the model’s ability to discern which component contributes more prominently to the final outcome. To address this limitation, gate valves \({G}_{SA}\) and \({G}_{CA}\) are introduced in the output stages of spatial attention and channel attention respectively, enabling a weighting mechanism for their respective results. Both \({G}_{SA}\) and \({G}_{CA}\) serve as learnable parameters that can be automatically generated based on current size during calculations, with gradients computed during backpropagation for parameter updates. The gating mechanism assigns higher weights to one party if it performs better in feature extraction while assigning lower weights to the other party accordingly. Through this process, the model learns about the contributions made by spatial attention and channel attention, thereby achieving weight measurement. Below provides a detailed explanation of both types of attention calculation processes along with an elaboration on the gating mechanism.

G-SWPA network architecture. The parallel integration of spatial attention and channel attention is achieved through a gating mechanism, which dynamically regulates the impact of both types of attention on feature extraction to enhance the effectiveness of feature information acquisition. Both G_SA and G_CA serve as learnable parameters that can be automatically generated based on current size during calculations, with gradients computed during backpropagation for parameter updates.

Spatial attention computation

In the G-SWPA spatial attention computation, it effectively reduces the complexity of attention computation from \(O\left({n}^{2}\right)\) to \(O\left(nm\right)\) (where \(n\) represents the number of marks and \(m\) denotes the dimension of the projection vector, with \(n\ll m\)). This improvement is particularly beneficial for larger-sized feature information as it significantly reduces computational requirements. For the input feature map \(X\), the dimensions of width \(W\), height \(H\), and depth \(D\) are first combined to form shape \(HWD\times C\). Subsequently, three linear layers are employed to calculate \({Q}_{SW}\), \({K}_{SW}\), and \({V}_{Spatial}\) using the following formulas:

Where, \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{k}\) and \({W}_{V-Spatial}\) are the projection weight matrices of \({Q}_{SW}\), \({K}_{SW}\) and \({V}_{Spatial}\), respectively.

The specific calculation of spatial attention involves the projection of \({K}_{SW}\) and \({V}_{Spatial}\) onto \(m\) dimensions to obtain \({K}_{Proj}\) and \({V}_{Proj}\), followed by transposing \({K}_{Proj}\) and multiplying it with \({Q}_{SW}\). Afterward, \(Softmax\) is applied, followed by multiplication with \({V}_{Proj}\) to derive the spatial attention force \({\stackrel{\sim}{X}}_{s}\). Finally, multiplication with \({G}_{SA}\) yields the ultimate spatial attention force \({\widehat{X}}_{s}\). The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Where, \({Q}_{SW}\), \({K}_{Proj}\), and \({V}_{Proj}\) represent the matrix of the shared query, projection shared key, and projection space value layer respectively, \(d\) is the size of each vector, and \({G}_{SA}\) represents the spatial attention gating parameter.

Channel attention computation

To further capture the interdependence between feature channels, we employ the dot product method for calculating the channel attention map. For the input feature map \(X\), we utilize the same \({Q}_{SW}\) and \({K}_{SW}\) as in the spatial attention module, while employing a linear layer to independently compute the \(V\) value of channel attention as follows:

Where \({W}_{V-Channel}\) is the projected weight matrix of \({V}_{Channel}\).

The specific channel attention calculation involves the multiplication of the transpose of matrix \({Q}_{SW}\) with \({K}_{SW}\), followed by the multiplication with \({V}_{Channel}\) after \(Softmax\) to obtain the channel attention diagram \({\stackrel{\sim}{X}}_{c}\). Finally, it is multiplied by \({G}_{CA}\) to derive the final spatial attention diagram \({\widehat{X}}_{c}\). The precise calculation formula is as follows:

Where, \({Q}_{SW}\), \({K}_{SW}\), and \({V}_{Channel}\) represent the matrix of the shared query, shared key, and channel value layer respectively, \(d\) is the size of each vector, and \({G}_{CA}\) represents the channel attention gating parameter.

After calculating the spatial attention and channel attention, it is essential to combine the results of both attentions. Since the final results of these calculations have identical shapes, this paper employs a direct addition method for integration. This approach effectively demonstrates the role of gating parameters set in this study and ensures that the final output attention results are not weakened to any extent. Once fusion is completed, the original input is merged based on the ResNet45 structure. Subsequently, two convolutional layers are applied to transform the merged result again, facilitating a more comprehensive entanglement of both types of attention information. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Where, \({\widehat{X}}_{s}\), \({\widehat{X}}_{c}\) and \(X\) represent spatial attention graph, channel attention graph and input feature map respectively, and \({Conv}_{1}\) and \({Conv}_{2}\) are convolution blocks of and 3 × 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 × 1, respectively.

Conv fusion module

After the feature extraction of both scales at each stage, it is necessary to further integrate the feature information from these two scales. However, self-attention computation introduces a complexity of \(O\left({n}^{2}\right)\), which significantly increases computational costs during training and inference when dealing with long sequences. Moreover, considering all locations for correlation calculations in self-attentional mechanisms can lead to sparse correlations over long distances, resulting in delayed or inaccurate information transfer. To address these issues, this paper directly employs convolution methods to fuse the feature information from both scales in the first three stages of the encoder. This approach not only resolves the aforementioned problems but also captures rich contextual information from adjacent spatial positions through convolutions, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of feature extraction. Specifically, one scale’s feature information is initially downsampled to match the size of another scale’s features before applying two three-dimensional convolution operations for final fusion. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Where \(Downsample\) is the downsampling layer, and the maximum pooling is used to scale in the three directions of width, height and depth, the specific scaling ratio needs to be determined according to the data set, \(Cat\) is the concatenation operation, and \({Conv}_{3}\) and \({Conv}_{4}\) are two 3 × 3 × 3 convolution blocks.

Gated dual scale cross attention module (G-DSCAM)

The bottleneck section consists of a single stage, similar to the encoder section, comprising two coding blocks and a feature fusion block. The encoding block passes the output to the feature fusion block after attention calculation. Unlike the encoder section, convolution operation is not employed in the feature fusion module of the bottleneck section. Specifically, after four operations of feature extraction and downsampling, the size of features has been reduced to a relatively small range, making self-attention calculation complexity acceptable. To expand receptive field in the final layer, two sizes of feature information can be fully fused and entangled. Drawing inspiration from SENet46 and DS-TransUNet29 models, this paper introduces gated dual-scale cross-attention module (G-DSCAM) primarily for dual-scale feature fusion in volumetric images. This module is utilized for carrying out feature fusion operation at the last layer to enhance obtained feature information.

The G-DSCAM proposed in this paper utilizes the self-attention mechanism for computation and incorporates a standard Transformer12 block to fully capture the feature information from both volume scales, thereby achieving a more effective long-term dependency relationship. To regulate the impact of these two types of feature information on the final output after self-attention calculation, two gated valves are designed in this study. Similar to those in G-SWPA, these gated valves automatically adjust the proportion of each type of feature information to enhance model generalization. Furthermore, inspired by ResNet45, this paper ensures that newly obtained features are at least as good as the original ones by adding them back to the input after completing self-attention calculation, thus preserving the validity of feature information. Finally, the two features of the self-attention calculation are spliced and output after two convolution layers.

G-DSCAM network architecture. By reducing the dimensionality of coarse-grained and fine-grained features, self-attention calculation is performed, while utilizing two gates to dynamically adjust the relative proportions of these feature types. Both \({G}_{1}\) and \({G}_{2}\) serve as learnable parameters that can be automatically generated based on current size during calculations, with gradients computed during backpropagation for parameter updates.

The specific architecture of G-DSCAM is illustrated in Fig. 5. The proposed G-DSCAM in this paper facilitates the interaction between two branches with different scales. Subsequently, this paper elaborates on the interactive operation of the coarse-grained feature information branch as an exemplification, which can also be applied to the fine-grained feature information branch. During actual operation, both branches execute operations simultaneously. In this study, we denote the input fine-grained feature information as \({F}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{(H/2\times W/2\times D/2)\times C}\) and the coarse-grained feature information as \({F}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times D\times C}\). Initially, \({F}_{1}\) is average pooled and then flattened to obtain a vector \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{1\times 1\times 1\times C}\) that represents the entire fine-grained feature information. The specific calculation formula is presented below:

Where \(Avgpool\) refers to the average pooling operation, \(Flatten\) refers to the flattening operation, and the resulting \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{1}\) is a global abstract information representing \({F}_{1}\) that will interact with \({F}_{2}\) at the pixel level.

Next, \({F}_{2}\) is flattened from a 3D structure to a 1D structure resulting in \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\). \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{1}\) is then spliced onto \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\) and fed into the Transformer for self-attention calculation. The gating parameter \({G}_{2}\), designed in this paper, is multiplied to obtain a new \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{(1+H\times W\times D)\times C}\) which undergoes \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{1}\) removal after calculation to yield the final \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\). \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\) is then restored back to its original 3D structure resulting in feature information \({\widehat{F}}_{2}\) after interaction with the input feature. This information is added back to the original input feature using the following specific formula:

Where \({G}_{2}\) refers to the gate parameter of the coarse-grained branch, \(Flatten\) refers to the flattening operation, \(Cat\) refers to the splicing operation, \(Transformer\) refers to the self-attention calculation, \(Reshape\) restores the feature information from one dimension to three dimensions, \({F}_{2}\) is the original input, and \({\stackrel{\sim}{F}}_{2}\) is the intermediate variable after the self-attention calculation, \({\widehat{F}}_{2}\) is the final output. After the aforementioned sequence of operations, coarse-grained features are able to acquire information from fine-grained branches, and vice versa. Consequently, the G-DSCAM module proposed in this study facilitates effective fusion of multi-scale branch features, thereby achieving enhanced segmentation performance. The proposed gating parameters \({G}_{1}\) and \({G}_{2}\), similar to the aforementioned gating mechanism, are learnable parameters that can be automatically updated during backpropagation. It is worth noting that if one party demonstrates superior feature extraction performance, the gating mechanism will assign a higher weight to it while assigning a lower weight to the other party, thereby achieving weight measurement.

Finally, the coarse-grained feature information is downsampled to match the size of the fine-grained feature information. The two types of features are concatenated and passed through two convolutional layers for final fusion. The specific calculation process follows the Conv-Fusion method described, which will not be reiterated here.

Decoder

In the decoder part, this paper adopts a symmetric structure with the encoder, which also consists of three stages. Each stage comprises a decoding block composed of an upper sampling layer and a G-SWPA submodule. Unlike the lower sampling layer, deconvolution is employed in the upper sampling layer to progressively restore low-resolution features to high resolution. Additionally, skip connections are utilized to facilitate cross-level information transfer for preserving more details from low-level features, mitigating gradient vanishing issues and addressing sample imbalance problems. This approach aims to enhance model performance and generalization ability by promoting better preservation of fine-grained segmentation details. Following the incorporation of skip connections and upsampling operations, the G-SWPA submodule is employed again in order to extract feature information while effectively integrating it with that from the encoder part.

Finally, to further integrate the high-resolution information from the original input with the semantic information extracted by the decoder, this paper employs a direct convolution of the original input and subsequently concatenates it with the output of the decoder. This is followed by two convolution operations to generate the final mask prediction.

Loss function

The loss function in this paper combines the soft dice loss25 and the cross entropy loss, thereby integrating both local pixel-level similarity and global category information. By incorporating these two loss functions, the model can effectively leverage contextual information surrounding each pixel for accurate classification and precise assignment of category labels. The specific calculation method is as follows:

Where, \(G\) refers to the set of real results, \(P\) refers to the set of predicted results, \({P}_{i,j}\) and \({G}_{i,j}\) represent the probability output of class \(i\) at voxel \(j\) and the one-hot coded true value respectively. \(I\) is the number of voxels; \(J\) is the number of classes.

Experiments

In order to validate the performance of the DS-UNETR++ model proposed in this paper, a comparative analysis is conducted with convolution-based image segmentation models including U-Net2, nnUNet26, 3D UX-Net43, as well as Transformer-based image segmentation models such as SETR47, TransUNet42, TransBTS48, CoTr49, UNETR22, UNETR++23, IMS2Trans50, Hsienchih Ting’s Model51, Swin-UNet37, MISSFormer52, Swin-UNETR44, LeVit-UNet53, PCCTrans54, Guanghui Fu’s Model55, MedNeXt56 and nnFormer39. The experiments are carried out on four diverse datasets, namely Brain Tumor Segmentation Task (BraTS), Multi-organ CT Segmentation Task (Synapse), automatic cardiac Diagnostic Segmentation Task (ACDC), and Medical Image Segmentation Decathlon (MSD) Heart Segmentation task (Heart). The datasets used are briefly introduced in this section, followed by an explanation of the experimental methodology employed in this paper, and finally an outline of the metrics adopted.

Dataset introduction

Brain tumor segmentation dataset (BraTS)57

The dataset comprises 484 MRI images, each containing four modalities: FLAIR, T1w, T1gd, and T2w. There are three label categories: edema (ED) as label 1, non-enhanced tumor (NET) as label 2, and enhanced tumor (ET) as label 3. The competition necessitates region-based segmentation with the identification of three sub-regions: whole tumor (WT), which includes labels 1, 2, and 3; tumor core (TC), comprising labels 1 and 3; and enhanced tumor (ET), consisting of label 3 exclusively. For data partitioning purposes in this study, it is divided into two parts with a ratio of training set to test set being 80%,20%, respectively. Evaluation metrics employed include Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and the Hausdorff distance at the threshold of the topmost five percentiles.

Multi-organ ct segmentation dataset (synapse)58

The Synapse dataset consisted of 30 abdominal CT scan images, which were partitioned into 18 training samples and 12 evaluation samples using the UNETR++11 processing method. This dataset encompassed eight distinct categories that required segmentation: spleen, right kidney, left kidney, gallbladder, liver, stomach, aorta, and pancreas. In this study, the evaluation metrics employed were DSC (Dice similarity coefficient) and HD95 (Hausdorff distance at 95th percentile).

Automated cardiac diagnostic segmentation dataset (ACDC)59

The ACDC dataset comprises 3D MRI images of the heart, encompassing a multi-class. Out of these, 100 data points were labeled and divided into 80 training sets and 20 test sets. The labels in this dataset include right ventricle (RV), myocardium (MYO), and left ventricle (LV). In this study, the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) was employed as an evaluation metric to compare against other models.

Heart segmentation dataset (heart)57

The dataset represents the second subset in the Medical Segmentation Decathlon, focusing on segmenting the left atrium from the provided MRI dataset. It involves a single-class segmentation task. A total of 30 patients were included, and their MRI images were divided into 20 training sets and 10 test sets. The evaluation metric used was DSC.

The indicators of the above four data sets are elucidated in Table 1, aiming to facilitate the visualization of the primary indicator data for each dataset.

Experimental details settings

The data set preprocessing in this paper follows the exact same approach as the baseline model UNETR++, including data cropping, scaling, etc. The program is executed on a single NVIDIA 4090 24G GPU in the Ubuntu 20.04 system environment. The PyTorch framework used is torch1.11.0 + cu113. For all data sets, the learning rate was set to 0.01 and weight decay to 3e-5. The Loss function employed was Dice + CE Loss. This paper evaluates each index using a model without pre-training weight training. This paper employs the identical data augmentation strategy utilized by the baseline model and implements model checkpointing to acquire the optimal weights. Please refer to Table 2 for details on the main environment settings.

Evaluation indicators

The paper introduces two primary evaluation indices: Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and Hausdorff Distance _95 (HD95). Among them, HD95 is employed to quantify the dissimilarity between the two sets, with smaller values indicating higher similarity. The choice of 95% is made to exclude outliers comprising 5% of the data. HD95 can be computed as follows:

Where, \({G}^{{\prime }}\) and \({P}^{{\prime }}\) represent the true label set and the predicted label set for all voxels, respectively. \({d}_{{G}^{{\prime }}{P}^{{\prime }}}\) is the maximum 95th percentile Hausdorff distance from the predicted value to the true value side, \({d}_{{P}^{{\prime }}{G}^{{\prime }}}\) is the maximum 95th percentile Hausdorff distance from the true value to the predicted value side, \({g}^{{\prime }}\) is the single voxel true value, \({p}^{{\prime }}\) is the single voxel predicted value, and \(d\) is the distance.

The Dice similarity coefficient is primarily utilized for quantifying the similarity between two sets, with a value range of [0, 1]. The higher the value, the greater the resemblance between the two sets. The calculation formula for DSC is as follows:

Where, \(G\) refers to the set of real results, \(P\) refers to the set of predicted results, \({G}_{i}\) and \({P}_{i}\) represent the true and predicted values of voxel \(i\), respectively, and \(I\) is the number of voxels.

Results

In this paper, the experimental results of four datasets are summarized and analyzed. Subsequently, a comparative analysis was conducted on various convolution-based image segmentation models including U-Net2, nnUNet26, 3D UX-Net43, as well as Transformer-based image segmentation models such as SETR47, TransUNet42, TransBTS48, CoTr49, UNETR22, UNETR++23, IMS2Trans50, Hsienchih Ting’s Model51, Swin-UNet37, MISSFormer52, Swin-UNETR44, LeVit-UNet53, PCCTrans54, Guanghui Fu’s Model55, MedNeXt56 and nnFormer39. Ablation experiments were then performed to further validate the effectiveness of the enhanced module proposed in this paper. Finally, visual segmentation results were presented to intuitively demonstrate the model’s performance.

Comparison of different segmentation models

BraTS dataset

Table 3 presents the results of DSC and HD95 indicators on the BraTS dataset for various models, calculating the final average values across three categories. The model performance in this study adopts single model accuracy without utilizing pre-training weights during training. The data in the table clearly demonstrates that UNETR++23 outperforms other models significantly, achieving an average HD95 of 5.94 and a DSC of 82.49%. In contrast, DS-UNETR++ surpasses UNETR++23 in all indicator categories, with an average HD95 of 4.98 and a DSC of 83.19%, resulting in a decrease of 0.96 in average HD95 and an increase of 0.7% in average DSC compared to UNETR++23. Particularly noteworthy is its superior performance in TC category segmentation where it exhibits a remarkable improvement by increasing the DSC index by 1.22% while reducing the HD95 index by 1.39, achieving both the highest DSC index and lowest HD95 index among all models including UNETR++23, thus highlighting its more effective performance.

Synapse dataset

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of various models based on the DSC and the HD95 metrics on the Synapse dataset, including the overall average performance across eight segmentation categories. Due to the diversity of segmentation categories, different models exhibit varying degrees of effectiveness across these categories. Notably, UNETR++23 demonstrates superior performance across multiple categories, achieving the highest average DSC and HD95 values, recorded at 87.22% and 7.53, respectively. In comparison, DS-UNETR++ surpasses these results, attaining an average DSC of 87.75%, which is a 0.53% improvement over the baseline model, and an average HD95 of 6.67, indicating a 0.86 reduction compared to the baseline. Furthermore, in the evaluation of specific category metrics, DS-UNETR++ excels in six categories: right kidney, left kidney, gallbladder, liver, aorta, and pancreas. Particularly, the segmentation performance for the right kidney and pancreas shows significant improvement, with increases of 4.87% and 1.05%, respectively, over the baseline model. These findings underscore the enhanced segmentation capabilities of the DS-UNETR++ model on the Synapse dataset, highlighting its superiority and robustness in medical image segmentation tasks.

ACDC dataset

Table 5 presents the DSC index results of various models on the ACDC dataset and calculates their final average values for three categories. The data in the table indicates that each model performs well overall, with good segmentation performance across all categories. Notably, nnFormer39 and UNETR++23 stand out with UNETR++23 achieving an impressive average DSC of 92.83%. DS-UNETR++, however, surpasses both models with an average DSC of 93.03%, which is 0.2% higher than the baseline model’s score. In terms of specific category segmentation, DS-UNETR++ improves right ventricular segmentation by 0.34% compared to the baseline model, demonstrating more effective performance in this area. Figure 6 compares training curves between UNETR++23 and DS-UNETR++ using ACDC data set (Figure (a) and Figure (b), respectively). As shown in the figure, DS-UNETR++ exhibits a more stable training process with relatively small fluctuations after approximately 500 rounds.

Heart dataset

The results of DSC indexes for various models on the Heart dataset are presented in Table 6, along with the calculation of the final average per category. It is evident from the data that nnUNet26 and UNETR++23 exhibit excellent performance, achieving DSC indexes of 93.87% and 94.41%, respectively. However, DS-UNETR++ outperforms them all with a remarkable DSC index of 94.51%. Despite being a single-category segmentation task with relatively well-defined segmented areas, there is noticeable disparity among the models’ performances. Nevertheless, DS-UNETR++ still achieves the best outcome, demonstrating its superior generalization capability and overall stronger performance. Figure 7 illustrates a comparison between training curves for UNETR++23 and DS-UNETR++ models on the Heart dataset (as shown in Figures (a) and (b), respectively). Notably, UNETR++23 exhibits considerable fluctuations even after 300 rounds, while DS-UNETR++, on the other hand, achieves stability faster—demonstrating its ability to converge more efficiently.

Table 7 presents the parameter counts and computational complexities of each model. “Params” denotes the total number of parameters during model training, while “FLOPs” represents floating-point operations per second. The data in Table 7 indicate that, compared to the baseline model UNETR++23, our proposed model exhibits a modest increase in both parameter count and computational complexity but achieves a higher Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) value. This suggests that the additional parameters and computational resources allocated to our model are effectively utilized. Furthermore, when compared to UNETR22 and nnFormer39, the parameter counts of these models are 1.4 and 2.2 times higher, respectively, and their computational complexities are 1.9 and 5.2 times greater than those of our proposed model. Despite this, neither UNETR nor nnFormer achieve as high a DSC value as our model, further underscoring its good performance.

To further validate the robust performance of the proposed model under varying image quality conditions, this study employs the Heart dataset for comparative experiments. Prior to model training, we increased the sampling stride parameter and reduced the resolution of the input data to assess the model’s performance under these altered conditions. As shown in Table 8, DS Str. denotes the downsampling stride. Based on the dual-branch encoding network presented in this paper, each experimental group utilizes two stride parameters. This study conducted three sets of experiments, with the last two serving as comparative verifications. The data in the table indicate that for the first set of comparative experiments (Resolution Reduction 1), the input data resolution for the first branch was reduced to half of the original, yielding a DSC value of 94.47%, which is insignificantly different from the best result experiment at 94.51%. For the second set of comparative experiments (Resolution Reduction 2), the input data resolution for the second branch was reduced to one-fourth of the original, resulting in a DSC value of 94.45%, also insignificantly different from the best result experiment. These two sets of comparative experiments demonstrate that the proposed model exhibits strong robustness and can maintain high performance even when the quality of the input images changes.

Comparison of ablation experiments

The ablation experiment results of this paper are presented in Table 9. Specifically, the ACDC dataset was utilized to investigate the impact of DS-UNETR++ on different modules. The evaluation indicators employed were the average Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and Hausdorff Distance at 95% (HD95) for the three categories. To ensure consistency in the experimental setup, our own equipment was used to test the baseline model UNETR++23. The table displays a DSC value of 92.54% and an HD95 value of 1.20 for this baseline model. Building upon UNETR++23, this study introduces a dual-scale efficient paired attention (EPA) block as part of the encoder, which incorporates feature information from two scales. This design validates the effectiveness of our proposed dual-branch feature coding subnetwork. The final evaluation indexes for DSC and HD95 are reported as 92.78% and 1.15 respectively, demonstrating improvements compared to the baseline model with an increase in DSC by 0.24% and a decrease in HD95 by 0.05. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the dual-branch encoding subnetwork proposed in this study. Building upon this foundation, in the second stage, the EPA23 block was replaced with the enhanced Gated Shared Weighted Paired Attention block (G-SWPA) The final evaluation indexes of DSC and HD95 were 92.90% and 1.11 respectively, indicating a marginal increase of 0.12% in DSC and a reduction of 0.04 in HD95. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the improved G-SWPA module proposed in this study. Additionally, building upon the second stage, we introduced the Gated Dual-Scale Feature Image Fusion module (G-DSCAM) developed within this paper. The ultimate evaluation indexes for DSC and HD95 reached 93.03% and 1.10 respectively, with an additional improvement of 0.13% observed in DSC index alone, further validating the efficacy of our designed G-DSCAM module presented herein. Therefore, considering all ablation experiments conducted herein, it can be concluded that several modules designed in this study played pivotal roles and ultimately led to superior performance of the DS-UNETR++ model compared to the baseline model as a whole.

Visualize segmentation results

The visual segmentation results of the BraTS dataset are presented in Fig. 8a, showcasing a total of 5 samples. These samples are primarily compared with the baseline model, while incorporating real labels in the final row for enhanced analysis. Due to the absence of well-defined regions in brain tumor segmentation, certain ET regions appear as scattered dots, making segmentation more challenging. Both the baseline model and DS-UNETR++ exhibit room for improvement in accurately segmenting ET and TC regions when compared to ground truth labels. However, DS-UNETR++ demonstrates superior performance in segmentation compared to the baseline model. Notably, in cases three and four, DS-UNETR++ achieves closer alignment with the real label whereas UNETR++23 exhibits missing segments.

The visual segmentation results of the Synapse dataset, as well as five examples, are presented in Fig. 8b. Despite the large number of categories in this dataset, DS-UNETR++ demonstrates robust performance. From the figure, it is evident that our proposed model outperforms the baseline model in segmenting Rkid. Specifically, examples 1, 3, and 5 illustrate that UNETR++23 produces hollow predictions leading to incomplete segmentation; whereas DS-UNETR++ consistently aligns with the real labels. Furthermore, considering the second and fourth examples, UNETR++23 exhibits incomplete organ segmentation with undivided regions; however, DS-UNETR++ accurately segments corresponding organ regions at identical positions within the same section image of these examples.

The visual segmentation results of the ACDC dataset are presented in Fig. 9a, showcasing a total of 5 examples. It is evident from the figure that DS-UNETR++ exhibits notable advantages in image segmentation, particularly in the second example where it accurately segments the shape of RV compared to the ground truth label, while the baseline model only captures a partial segment. Furthermore, DS-UNETR++ demonstrates commendable performance in reducing false-positive predictions as observed in the fifth example; unlike UNETR++23, DS-UNETR++ correctly predicts RV without any errors. These findings substantiate that our proposed model delivers enhanced efficiency and superior identification capabilities.

The visual segmentation results of the Heart dataset are presented in Fig. 9b, showcasing three examples in total. Due to the presence of a single category and relatively complete segmentation regions, the difficulty level for segmentation is comparatively low. From the figure, it can be observed that both the baseline model and DS-UNETR++ exhibit commendable performance; however, certain disparities still exist. In terms of segmenting smaller regions, DS-UNETR++ demonstrates more comprehensive segmentation with segmented region sizes closer to the real labels compared to UNETR++23. Consequently, overall performance indicates that DS-UNETR++ outperforms its counterpart and exhibits greater potential.

Discussion

The limitations of the pure convolutional architecture model are evident, as it fails to establish effective long-term dependencies. Although U-Net2’s inclusion of jump connections has mitigated this issue, a semantic gap arises due to the disparity in semantic information between shallow and deep features. However, employing a pure Transformer12 architecture for 3D image segmentation tasks would entail significant computational costs. Hence, combining convolution with Transformer12 and utilizing a hybrid image segmentation approach proves to be an optimal choice.

The research in this paper focuses on the hybrid image segmentation method. Based on the experimental results presented in the previous chapter, it is evident that the proposed method is highly effective. This paper introduces three improvements. Firstly, a transition from single-branch to two-branch image segmentation is implemented. During the experimentation phase, various combinations of scale information from multiple branches are explored for different datasets. It was observed that incorporating small-scale feature information at an early stage of the encoder does not contribute positively to model performance. After conducting numerous experiments and considering scale information integration, an appropriate combination was ultimately selected. Secondly, this paper enhances the gated shared weight pairs of attention blocks (G-SWPA). In comparison to the EPA23 module in the baseline model, this study introduces a gated valve for each attention output to regulate its impact on model performance. During experimentation, various positions within the G-SWPA module were considered for incorporating these gated valves. After evaluating their effects at different stages such as input initialization, post dot product operation, and final output stage of attention components, it was observed that adding the gating valve in the output stage yielded optimal results. Consequently, this paper concludes by proposing the inclusion of this designed gating valve in the output stage. Finally, a gated dual-scale Cross attention module (G-DSCAM) is devised to effectively integrate feature information from two scales. Various experiments are conducted in this study to explore the optimal position of the gating mechanism. Additionally, a ResNet45 structure is incorporated after the attention calculation stage to ensure output reliability.

The improvement of the aforementioned three aspects can be observed from the results of the ablation experiment presented in Table 9. The incorporation and enhancement of each module positively contribute to enhancing model performance. In the final experiment, this study evaluates the model’s performance on four datasets. Each dataset exhibits varying degrees of improvement based on DSC and HD95 metrics, as evident from data provided in Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6. Notably, significant improvements are observed for the BraTS dataset (Table 3). To gain a more intuitive understanding of DS-UNETR++’s specific effects on image segmentation process, this paper visualizes each dataset with accompanying real labels for comparison purposes. The method proposed in this paper can be seamlessly integrated into clinical environments and readily adapted for application in various other domains. Specifically, the G-SWPA module designed herein serves as an effective feature extraction unit. The weight sharing and gating mechanisms embedded within it are versatile enough to be applied across diverse fields, including urban landscape imagery, remote sensing image segmentation, natural scene images, and even feature extraction in natural language processing. Furthermore, this study implements a modular integration design at the code level for both G-SWPA and G-DSCAM, facilitating ease of deployment and adaptability.

Although DS-UNETR++ has achieved satisfactory results, it still possesses certain limitations. Firstly, in comparison to numerous lightweight model architectures, this study may necessitate a greater allocation of computing resources. Although the use of a dual-branch feature extraction subnetwork undoubtedly enhances the model’s ability to extract features, it also introduces additional computing overhead. Despite significant advancements in computing power and memory capacity, the pursuit of enhanced performance metrics through reduced parameter counts and computational complexity remains a key developmental direction for models and a continuous innovation goal for researchers. Secondly, in the first three stages of the encoder, only convolution is used to fuse the dual-scale features. Compared to the approach utilizing attention mechanisms, the proposed method indeed reduces computational complexity; however, the fusion efficacy may not be optimal, potentially impacting subsequent decoding performance. Therefore, this limitation warrants further enhancement. Moreover, despite the model’s relatively low parameter count and computational complexity, there remains a risk of overfitting, necessitating the implementation of strategies to mitigate this concern.

In light of the current limitations of this method, we will focus on enhancing our approach in the following three areas: (1) By leveraging existing lightweight structural designs, we aim to optimize the dual-scale feature encoding network presented in this paper, thereby reducing the computational complexity of the model; (2) We will refine the feature fusion within the encoder and introduce a lightweight attention mechanism based on convolutional operations to further enhance the fusion effect without increasing model complexity. (3) To mitigate the risk of overfitting, we will employ techniques such as regularization and multiple cross-validation, and explore the design of data augmentation methods specifically for medical images to further minimize the risk of overfitting.

Conclusions

This paper introduces a 3d medical image segmentation network based on gated attention blocks and dual-scale cross-attention mechanism. This architecture is designed to extract multi-scale features from two perspectives, thereby reducing the model’s reliance on specific feature sets. A novel Gated Shared Weighted Paired Attention block (G-SWPA) is proposed, which employs parallel spatial and channel attention modules to share query and key weights. This design not only captures comprehensive spatial and channel information but also reduces the number of parameters. Additionally, a gating mechanism is incorporated to dynamically adjust the influence of spatial and channel attention, enhancing the effectiveness of feature extraction. In the bottleneck stage, a Gated Dual-Scale Cross-Attention Module (G-DSCAM) is introduced to expand the receptive field by dimensionality reduction, promoting the fusion and entanglement of feature information across different scales. The proposed method was rigorously evaluated on four public medical datasets. In the BraTS dataset, the HD95 index drops to 4.98, while the DSC index rises to 83.19%, which is 0.86 lower and 0.53% higher than the baseline model. In the Synapse dataset, the HD95 value is 6.67 and the DSC value is 87.75%, which is 0.86 lower and 0.53% higher than the baseline model. These experimental results demonstrate that DS-UNETR++ excels in multi-organ segmentation tasks, offering a promising approach for this domain.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper may be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Umirzakova, S., Ahmad, S., Khan, L. U. & Whangbo, T. Medical image super-resolution for smart healthcare applications: a comprehensive survey. Inf. Fusion 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102075 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. PT III 9351, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (2015).

Zheng, Z. Z. et al. AFFU-Net: attention feature fusion U-Net with hybrid loss for winter jujube crack detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107049 (2022).

Song, H. J., Wang, Y. F., Zeng, S. J., Guo, X. Y. & Li, Z. H. OAU-net: outlined attention U-net for biomedical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104038 (2023).

Hou, Q. Y. et al. ISTDU-Net: infrared small-target detection U-Net. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2022.3141584 (2022).

Lan, C. F., Zhang, L., Wang, Y. Q. & Liu, C. D. Research on improved DNN and MultiResU_Net network speech enhancement effect. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 26163–26184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12929-6 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. SAU-Net: a novel network for building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing images by reconstructing fine-grained semantic features. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 17, 6747–6761. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3371427 (2024).

Valanarasu, J. M. J., Sindagi, V. A., Hacihaliloglu, I. & Patel, V. M. KiU-Net: Overcomplete convolutional architectures for biomedical image and volumetric segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2021.3130469 (2022).

Sun, Q. et al. UCR-Net: U-shaped context residual network for medical image. Comput. Biol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106203 (2022).

Lin, H., Cheng, X., Wu, X. & Shen, D. C. A. T. Cross attention in vision transformer. In IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME). https://doi.org/10.1109/icme52920.2022.9859720 (2022).

Jafari, M., Francis, S., Garibaldi, J. M. & Chen, X. LMISA: a lightweight multi-modality image segmentation network via domain adaptation using gradient magnitude and shape constraint. Med. Image Anal., 102536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2022.102536 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (NIPS 2017), 30. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1706.03762 (2017).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929 (2021).

Li, B. et al. RT-Unet: an advanced network based on residual network and transformer for medical image segmentation. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 37, 8565–8582. https://doi.org/10.1002/int.22956 (2022).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Star-shaped window Transformer Reinforced U-Net for medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. SWTRU. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105954 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Brain tumor segmentation in MRI with multi-modality spatial information enhancement and boundary shape correction. Pattern Recognit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2024.110553 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Lightweight medical image segmentation network with multi-scale feature-guided fusion. Comput. Biol. Med. 182, 109204–109204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109204 (2024).

Zhan, B. C. et al. CFNet: a medical image segmentation method using the multi-view attention mechanism and adaptive fusion strategy. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104112 (2023).

Cai, W. T. et al. DFTNet: dual-path feature transfer network for weakly supervised medical image segmentation. IEEE-ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 20, 2530–2540. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2022.3198284 (2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Sparse dynamic volume TransUNet with multi-level edge fusion for brain tumor segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 172, 108284–108284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108284 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Brain tumor segmentation based on the fusion of deep semantics and edge information in multimodal MRI. Inf. Fusion. 91, 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2022.10.022 (2023).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. UNETR: Transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. In 2022 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV 2022), 1748–1758. https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV51458.2022.00181 (2022).

Shaker, A. et al. UNETR++: Delving into efficient and accurate 3D medical image segmentation. arXiv:2212.04497 (2023).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J. Y. & Kweon, I. S. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1 (2018).

Milletari, F., Navab, N., Ahmadi, S. A. & Ieee V-Net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), 565–571. https://doi.org/10.1109/3DV.2016.79 (2016).

Isensee, F. et al. nnU-Net: Self-adapting framework for U-Net-based medical image segmentation. arXiv:1809.10486 (2018).

Chen, L. C. et al. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2017.2699184 (2018).

Chen, L. C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. Comput. Vis. ECCV 2018 PT VII. 11211, 833–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_49 (2018).

Lin, A. et al. DS-TransUNet: dual swin transformer U-Net for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3178991 (2022).

Bai, Q. Y., Luo, X. B., Wang, Y. X. & Wei, T. F. DHRNet: a dual-branch hybrid reinforcement network for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 17, 4176–4193. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3357216 (2024).

Khan, T. M., Naqvi, S. S. & Meijering, E. ESDMR-Net: A lightweight network with expand-squeeze and dual multiscale residual connections for medical image segmentation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.107995 (2024).

Wang, K. N. et al. SBCNet: scale and boundary context attention dual-branch network for liver tumor segmentation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28, 2854–2865. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2024.3370864 (2024).

He, Z. X., Li, X. X., Lv, N. Z., Chen, Y. L. & Cai, Y. Retinal vascular segmentation network based on multi-scale adaptive feature fusion and dual-path upsampling. IEEE Access 12, 48057–48067. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3383848 (2024).

Kuang, H. P., Yang, X., Li, H. J., Wei, J. W. & Zhang, L. H. Adaptive multiphase liver tumor segmentation with multiscale supervision. IEEE Signal. Process. Lett. 31, 426–430. https://doi.org/10.1109/LSP.2024.3356414 (2024).

Zhou, Q. et al. Boundary-guided lightweight semantic segmentation with multi-scale semantic context. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 26, 7887–7900. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2024.3372835 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021), 9992–10002. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00986

Cao, H. et al. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 205–218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25066-8_9

Peiris, H., Hayat, M., Chen, Z., Egan, G. & Harandi, M. A robust volumetric transformer for accurate 3D tumor segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2022 PT V 13435, 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16443-9_16 (2022).

Zhou, H. Y. et al. Volumetric medical image segmentation via a 3D transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32 (nnFormer), 4036–4045. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2023.3293771 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Axial-DeepLab: stand-alone axial-attention for panoptic segmentation. arXiv:2003.07853 (2020).

Valanarasu, J. M. J., Oza, P., Hacihaliloglu, I. & Patel, V. M. Medical transformer: gated axial-attention for medical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2021 PT I. 12901, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87193-2_4 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. Cornell Univ. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2102.04306 (2021).

Hin Lee, H., Bao, S., Huo, Y. & Landman, B. A. 3D UX-Net: a large kernel volumetric ConvNet modernizing hierarchical transformer for medical image segmentation. arXiv:2209.15076 (2023).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Swin UNETR: Swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in MRI images. In Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries, Brainles 2021, PT I 12962, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08999-2_22 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.90 (2016).

Hu, J., Shen, L., Albanie, S., Sun, G. & Wu, E. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011–2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpami.2019.2913372 (2020).

Zheng, S. X. et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2021, 6877–6886. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00681 (2021).

Wang, W. X. et al. TransBTS: multimodal brain tumor segmentation using transformer. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2021 PT I 12901, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87193-2_11 (2021).

Xie, Y. T., Zhang, J. P., Shen, C. H., Xia, Y. & CoTr Efficiently bridging CNN and transformer for 3D medical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2021 PT III. 12903, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87199-4_16 (2021).