Abstract

Despite the discovery of many plant-based drugs, research is still ingoing, in addition to using safer and more effective methods in the extraction process. Presently, Super Fluid Extraction (SFE) was applied to extract the mango seed kernels (MSK) at two operating temperatures 30 and 50 °C with studying their biological activities. MSK extract via SFE at operating temperatures 30 °C showed high yield 0.268 g compared to that at 50 °C. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis demonstrated high content of compounds such as gallic acid (68503.01 µg/mL), chlorogenic acid (6541.68 µg/mL), ferulic acid (2555.12 µg/mL) and ellagic acid (2479.42 µg/mL) MSK while at 50 °C the concentrations were low. Helicobacter pylori was highly inhibited by MSK extract via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C with inhibition zone 29.17 ± 0.29 mm, MIC 15.62 µg/mL and MBC 31.25 µg/mL, while at operating temperature 50 °C the inhibition zone was 24.67 ± 0.58 mm, MIC was 62.5 µg/mL and MBC was 125 µg/mL. Moreover, low hemolysis was recorded by H. pylori treated by MSK extract via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C compared to that at 50 °C. Excellent antioxidant with IC50 values of 4.34 and 10.5 µg/mL was recorded for MSK extract via SFE at operating temperatures 30 °C and 50 °C, respectively. The recorded IC50 values 151.64 ± 0.53 and 73.81 ± 1.68 µg/mL compared to IC50 202.83 ± 1.78 µg/mL and 85.78 ± 0.52 µg/mL indicated the efficacy of MSK extract via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C compared to that at 50 °C against prostate (PC3), and ovarian (SK-OV3) cancer cells lines, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to García-Mahecha et al.1, the Mangifera indica L. (Mango) is considered the greatest important tropical fruit that is cultivated and consumed by people all over the world. It is estimated that between 35 and 60% of fruits are thrown away during processing, often without any treatment, which causes environmental issues and financial losses. Seeds and peels (tegument and kernel) make up this waste2. Since the seed of mango has been identified as a bio-waste with a high level of bioactive chemicals (vitamin C, phenolic ingredients, carotenoids and nutritive fiber) that enhance the human health, it has attracted profound scientific attention3. Due to its antioxidant function, the seed of mango has also been shown to possess antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria4 and antitumor potential against cancer of the colon and breast5.

Mango seeds can be used as raw materials or as food additives, which might benefit producers financially by increasing the nutritional value that contributes to human health along with reducing the undesired environmental impact caused by mango seeds (bio-wastes)2. Mango seed kernels can be a rich source of various phenolic and antioxidant chemicals, according to Lim et al.6. Bioactive substances including; polyphenols, flavonoids and tannins have been demonstrated to have intriguing bio-functions resembling anti-inflammatory, cancer suppressing and antioxidant properties which can aid in the treatment of chronic illnesses7,8.

Several digestive systems-associated diseases such as peptic ulcer, gastritis and gastric adenocarcinoma were associated with H. pylori9. According to some reports, nearly half of the world’s populations are infected with H. pylori at some point in their lives. The management of H. pylori requires at least two antibiotics in addition toa proton pump inhibitor; however, the antibiotic resistance in bacteria, including H. pylori is becoming a major public health problem10. Alternative methods exploiting natural compounds extracted from plants have been widely investigated to discovering new compounds for H. pylori management11,12.

Cancer is a significant disease that has an impact on global health, as it is now the second greatest familiar cause of mortality worldwide, next to cardiovascular diseases12,13,14. The present investigations focused on two types of cancer including; prostate and ovary. According to recent studies, the most deadly gynecologic malignancy is ovarian cancer, and after diagnosis, fewer than half of patients live for more than five years15. Although it can strike women at any age, ovarian cancer is most frequently discovered after menopause16. Male prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men, accounting for 15% of all kinds of cancers17. According to James et al.18, the number of infected cases of prostate cancer will increase from 1.4 to 2.9 million cases in 2040 as compared to 2020.

In a previous report, the extracts of mango kernel possess activity against the growth of Klebsiella spp., Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas spp., and Enterococcus faecalis19. Also, Dorta et al.20 investigated the anti-yeast activity of mango seed and peel extracts, and found that Hanseniaspora uvarum, Dekkera anomala, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Zygosaccharomyces bisporus, Candida bracarensis, Candida parapsilosis Candida glabrata and Candida nivariensis were inhibited by the applied extracts.

Numerous scientists have recently focused on the utilization of supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), an alternative method to classical methods via chemical solvents, for the extraction of natural ingredients21. The ability to work at lower temperatures and the capability for quick extraction are unique features of SFE compared to other extraction methods. According to several reports, the obtained extracts via SFE are enriched with bioactive molecules in different fields22. The applied solvent in SFE is CO2 which avoids the breakdown of the extracted compounds as well as minimizes its sensitivity to oxidation21.

Several studies have investigated the biological activities of the extracted mango seeds by chemical solvents, but there are limited investigations as to the best of our knowledge about SFE-CO2 of kernels of mango seeds and their influences on H. pylori and cancer development of prostate and ovarian cells. Therefore, this investigation aims to evaluate the anti-H. pylori, anticancer and antioxidant potential of the extracted kernel of mango seeds via SFE.

Materials and methods

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) of Mango seeds kernels (MSK)

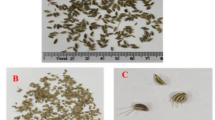

MSK were separated manually from seeds of ripe fruits (Mangifera indica, Anacardiceae family) which obtained from a farm at Jazan, Saudi Arabia (GPS: 17°00’54”N, 42°51’03”E), during the season of harvest at May 2025, then the kernels were dried for 5 days in open air. The dried kernels were grinded into powder and then injected in Supper Fluid Extraction (SFE) apparatus (ISCO-Sitec-adapted SFX 220 SFE system). SFE was operated at two temperatures, 30 and 50 °C, for extracting MSK, while pressure, dynamic and static time of extraction were constant at 25.16 MPa for 20 min and 40 min, respectively, during the process of extraction21. The extracted yield was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.6%).

HPLC analysis of MSK extract for flavonoids and phenols

The extract of MSK was subjected to HPLC analysis employing an Agilent 1260 series. The separation was completed by employing an Eclipse C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm, 40 °C). H2O (1st) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid dissolved in acetonitrile (2nd) at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min served as the HPLC’s mobile phase. Starting at 0 min (82% 1st), the phase of mobile was gradually changed in a straight gradient in the next regulation: 0 to 5 min (80% 1st); 5 to 8 min (60% 1st); 8 to 12 min (60% 1st); for minutes 12 to 15 (82% 1st); for minutes 15 to 16 (82% 1st); and for minutes 16 to 20 (82% 1st). The wavelength at 280 nm was recorded via a detector of HPLC. The injected quantity was 5 µL from each solution of the MSK extract23.

Activity of MSK against H. Pylori

To investigate the activity of MSK extract (from SFE at two different temperature settings, 30 and 50 °C) against H. pylori, the technique of well diffusion was used. The H. pylori colonies were first cultivated in Mueller-Hinton fluid at McFarland’s 0.5 threshold. Mueller-Hinton was amended by agar and 5% of horse blood was applied to promote H. pylori growth. Wells were done in agar and filled by MSK extract (50 µg/mL). After the incubation time (72 h) at 37 °C under a microaerophilic state, the radius of the inhibitory zone surrounding the well was measured24. Clarithromycin (50 µg mg/mL) was served as the study’s positive control. At two distinct temperature settings (30 and 50 °C), extracts of MSK from SFE were tested to evaluate its minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). The MTT tetrazolium reduction test was performed in 96-flat well microplates after the MSK extract from SFE was dissolved in Brucella broth in a range of 7.8 to 500 µg/mL. The inoculated plate wells by 50 µL of H. pylori (2 × 105 cells/mL) were incubated at 37 °C under a microaerophilic state for 72 h. The MTT reduction investigates was operated to estimate the MIC, which is the lowest dose that can inhibit H. pylori growth, or the lowest extract dose in the plate by which no H. pylori development took place. MTT (15 µL) was added after the MSK extract had been incubated for 15 min. The crystals of formazan were then melted by adding 80 µL from DMSO. The minimum absorbance (at 570 nm) was recorded using readers of microplate (Multimode Detectors DTX 800/880, Fullerton, CA). After the MIC test’s incubation period, 50 µL aliquots of MSK extract that did not show H. pylori development were intermixed with 150 µL of broth to determine MBC. These preparations (for 72 h at 37 °C) were incubated in a microaerophilic state. Absence of any color change in MBC after the addition of MTT, as previously noted, indicated that this sample contained the lowest dose of MSK extract.

The antioxidant properties of MSK extract

The antioxidant properties of MSK extracts and ascorbic acid (as standard control) were assessed by estimating the radical scavenging activity (RSA %) of MSK extracts employing the 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) assessment as illustrated by Abdelghany et al.25. The amount of Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was assessed via graph which indicates the dose of extract required to scavenge (50%) of the free radicals. The activity of radical scavenging was designed via the equation:

Hemolysis inhibition assay by MSK extracts

The hemolysin potential of H. pylori treated by MSK extracts at different doses of sub-MIC extract (25, 50, and 75%) was measured employing the Rossignol et al.26 technique. The exposed and unexposed H. pylori to extract was controlled to an OD 600 of 0.4, and then centrifuged at 21,000× g for 20 min. A suspension of fresh erythrocyte (2%) (Erythrocytes were obtained from corresponding author of the current paper Prof. Samy Selim (College of Applied Medical Sciences, Jouf University, Saudi Arabia) and 0.8 mL saline was then intermixed by 500 µL of supernatants, kept at 37 °C for 60 min, and then centrifuged (for 10 min, at 4 °C, and at 11,000× g). The erythrocyte suspension was mixed with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate to form complete hemolysis (positive control). By maintaining the erythrocytes in the LB broth under the same conditions as the control (positive), the negative control (unhemolyzed erythrocytes) was produced. The hemoglobin discharge was measured at 540 nm. The percentage alteration from that of untreated control cultures was used to express the hemolysis that occurred in the extract of cultures treated with sub-MIC. The % of hemolysis prevention was calculated after the liberation of haemoglobin in the existence of controls via the next formula:

Anti-cancer properties of MSK extract

The anti-cancer properties of MSK extracts were evaluated using the MTT assay27 versus the prostate cancer cells (PC3), ovarian cancer cells (SK-OV3), and normal human lung fibroblast cell line (WI-38) (obtained from ATCC, USA). A specific concentration of 5 × 104 cells per well was seeded in a 96-well sterile microplate and incubated at 37°C for 48 h with varying doses (31.25–1000 µg/mL) of MSK extracts, which were dissolved in DMSO. Doxorubicin (0.15 µg/mL) was served as the study’s positive control. The IC50 was valued via graph which signifies the dose of extract necessary to inhibit the proliferation (50%) of cancer cells. Morphological features of tested cancer cells were imagined.

Statistical evaluation

The trial outcomes were authenticated as mean standard deviation (± SD) of three times. Using a software of Graph Pad Prism V5 (San Diego, CA, USA) to assessment the result for one-way of variance (one-way ANOVA).

Result and discussion

The operator conditions of SFE either temperature or pressures besides dynamic and static extraction times are critical conditions for the extraction of natural materials. Presently the kernels were excluded from the mango seeds, subjected to SFE, and followed by HPLC analysis and biological testes as illustrated in Fig. (1). The yield quantity of mango seed kernels (MSK) was affected by the operating temperature of SFE, where the amount of the yield extract was 0.268 g at 30 °C whereas it was 0.240 g at 50 °C (Table 1). da Silva et al.28 mentioned that temperature is considered critical factor for controlling of extracted quantity and its contents of ingredients.

Unlike some reports that showed SFE at high temperature induced the releasing of several phenols and flavonoids, the present study found that high temperature affected the ingredient contents of MSK as analysed via HPLC (Figs. 2 and 3). Some compounds including gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid and methyl gallate were reduced from 68503.01 to 62985.64 µg/mL, 6541.68 to 5722.86 µg/mL, 2555.12 to 2219.01 µg/mL, 775.98 to 594.74 µg/mL, respectively in MSK employing SFE-CO2 at operating temperature transformed from 30 °C to 50 °C (Table 2). Moreover, rutin, daidzein, kaempferol and hesperetin were identified in MSK using SFE-CO2 at operating temperature 30 °C while were not detected at 50 °C, indicating that high temperature was destructive for some ingredients. On the other hand, only three ingredients namely syringic acid, catechin and coumaric acid were recognized in MSK with higher concentrations using SFE-CO2 at operating temperature 50 °C than that concentration at 30 °C. Lim et al.6 found that gallic acid was the main compound detected in MSK, followed by caffeic acid, rutin and Penta-O–galloyl-β-d-glucose. Numerous compounds including catechin, apigenin, rutin, gallic acid as main component, kaempferol and querectin were recorded via HPLC in Mangifera indica shell29. Also, García-Mahecha et al.1 mentioned that gallic acid represents the main constituent in kernel of mango seed followed by other constituents namely caffeic, tannic, chlorogenic, and cinnamic acids besides mangiferin, hesperidin and rutin.

Wide-ranging pharmacological utilizations are attributed to various parts such as fruit, leaves, bark and seeds of mango tree. However, no commercial application of mango seed kernel which is removed as waste during the processing of fruits in most cases. From the recorded findings, the exposed H. pylori to MSK extract indicated the antibacterial efficacy of this extract but with different inhibitory potential depending on the operator temperature of SFE. The zone of inhibition was 29.17 ± 0.29 mm at operating temperature 30°C while it was 24.67 ± 0.58 mm at operating temperature 50 °C (Table 3; Fig. 4). Generally, MSK extract showed excellent anti-H. pylori compared to the utilized standard. Also, the lowest MIC (15.62 µg/mL) and MBC (31.25 µg/mL) was recorded with the utilization of MSK extract at operating temperature 30°C of SFE-CO2. The calculated index of MBC/MIC documented that MSK extract possess bactericidal effects on H. pylori (Table 3). A previous investigation showed that the extract of mango seed kernel possess anti-enteric bacterial (Shigella dysenteriae) potential with MIC 95 ± 11.8 µg/mL30. Antibacterial activity of mango seed kernels was reported recently towards Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus, and Klebsiella sp4. Kernel of mango was extracted and tested against numerous bacteria including Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Salmonella typhi which exhibited bacteriostatic (at concentrations ranged from 3.1 to 50 µg/mL) and bactericidal (at concentrations ranged from 12.5 to 100 µg/mL) properties19. Additionally, antibacterial and anti-yeast activities of seed and peel extracts of mango were reported by Dorta et al.20 against different clinically pathogenic yeasts. Moreover, seed extracts exhibited lower quantities of MIC and minimum fungicidal concentration than the extracts of peel. The etiology of gastric ulcer includes numerous factors, from which the infection by H. pylori; mango seed kernel was applied to avoid the gastric ulcer31. Broad difference between the effects of MSK extracts using SFE at operating temperature 30°C and 50 °C, where the hemolysis % at 25, 50, and 75% MIC was 22.33 ± 0.29, 9.43 ± 0.12, and 3.17 ± 0.06%, respectively at operating temperature 30°C whereas it was 93.61 ± 2.31, 31.73 ± 0.64, and 7.13 ± 0.12%, respectively at operating temperature 50 °C in the presence of H. pylori (Figs. 5 and 6). The anti-hemolysis properties of MSK extracts were confirmed through these findings.

Figure 7 cleared the potent antioxidant of MSK extracted via DPPH which increased with increasing the dose of the extract. Slight differences of DPPH scavenging (%) between MSK extract using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C and ascorbic acid particularly at high concentrations were observed; for instance, DPPH scavenging was 93.6 and 93.3% at 250 µg/mL, 96 and 96.1% at 500 µg/mL, 98.2 and 97.8% at 1000 µg/mL, respectively. Low DPPH scavenging % was recorded using MSK extract via SFE at operating temperature 50 °C if compared to other extract or ascorbic acid. Moreover, IC50 confirmed the excellent antioxidant properties of MSK extracts using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C (4.34 µg/mL) and 50 °C (10.5 µg/mL) compared to IC50 of ascorbic acid (3.47 µg/mL). Pitchaon32 documented the antioxidant potential of MSK, and concluded that the antioxidant capability may be affected by the extraction process. Also, the antioxidant activity of different varieties of MSK was recorded by Mutua et al.33 with maximum DPPH scavenging 92.22%. The presence of phenolic compounds plays a critical role in the antioxidant properties of MSK extracts. HPLC indicated the presence of numerous phenols and flavonoids MSK extract using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C which recorded low IC50 of DPPH scavenging. Abdel-Aty et al.34 mentioned that scavenging free radicals by MSK was affected by its phenolic compounds with IC50 values of 47.3 µg/mL. Buelvas-Puello et al.35 obtained greater antioxidant activity of MSK extracted by SFE than using other classical extraction methods.

Anticancer activity

PC3 cell line proliferation was suppressed by MSK extract using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C and 50 °C. Toxicity/Viability was increased/decreased as the applied dose of the extract increased/decreased which reached 97.47/2.53% and 96.38/3.62% at 1000 µg/mL of MSK extract using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C and 50 °C, respectively. Moreover, MSK extracts using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C exhibited lower IC50 than that of the extract using SFE at operating temperature 50 °C which valued at (151.64 ± 0.53 µg/mL) and (202.83 ± 1.78 µg/mL), respectively (Fig. 8). In the same context, SKOV3 cell line was affected by MSK extract (Fig. 9) with low values of IC50 73.81 ± 1.68 µg/mL and 85.78 ± 0.52 µg/mL using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C and 50 °C, respectively.

The extracts using SFE at operating temperature 30 °C and 50 °C against normal WI-38 cells exhibited IC50 values of 279.56 ± 2.66 and 298.63 ± 2.87 µg/mL, respectively (Data not tabulated). The obtained result of extracts was compared to standard drug, where the IC50 values of doxorubicin (positive control) was 17 ± 0.33 and 10.43 ± 0.50 µg/mL against PC3 and SKOV3 cells (Data not tabulated). A recent review indicated that extracts of M. indica and their phytochemicals possess anticancer potential against breast cancer36. Other studies indicated that different parts of mango tree (seed, fruit shells, stem, roots and bark) were rich with a phenolic compound namely mangiferin37 which exhibited anticancer against ovarian cancer38 and prostate cancer39. The differences between our results of IC50 values and other studies may depend on the extraction methods, target cancer cells and extracted part of mango plant. Ballesteros-Vivas et al.40 attained rich MSK with anticancer activity versus colon cancer cells via SFE. Figures 10 and 11 showed the morphological changes in PC3 cell line and SKOV3, respectively which indicated that MSK extract via SFE at 30 °C was more effective on the tested cells than MSK extract via SFE at 50 °C. The morphological changes were greatly cleared at high doses from 250 to 1000 µg/mL which accompanied with apoptosis, alterations in the shape and size, besides shrinkages and cell appearance as floating cells. Moreover, the decline in the population of tested cell was obvious compared to unexposed cells to the tested extract (controls). Generally, several detected compounds in MSK via HPLC in the present study play a critical role for controlling H. pylori growth and cancer development as well as acting as antioxidant agents. For example, Mahmoud et al.41 confirmed the anticancer and antioxidant activities of ferulic acid, naringenin, catechins and gallic acid that detected in mango seeds extract. Anticancer and antioxidant of ellagic acid were reported previously42. Shaban et al.43 reported the anticancer activity of ellagic acid, coumaric acid and mangiferin in mango seeds extract. In a previous study, both catechin and gallic acid inhibited the growth of H. pylori, but gallic acid was effective than catechin44. Also, chlorogenic acid reflected anti-H. pylori activity via urease inhibition45. Via docking studies, chlorogenic acid9 and ferulic acid24 exhibited activity against against H. pylori. However, one of the limitations of the current investigation is employing pure separated compounds which was rare, and therefore is required in the further studies. Furthermore, our investigation did not study the action mechanism of extract constituents at genetic levels. Finally, only in vitro investigation was included in this repaper, limiting the investigation of the effectiveness of the MSK in the animal.

Effect of various doses of MSK extract on morphological fetures of PC3. Control (A), 31.25 µg/mL (B), 62.5 µg/mL (C), 125 µg/mL (D), 250 µg/mL (E), 500 µg/mL (F), and 1000 µg/mL (G) of the extract via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C. The existence of number (2) with the letters pointed the treatment by extract via SFE at operating temperature 50 °C.

Effect of various doses of MSK extract on morphological fetures of SKOV3. Control (A), 31.25 µg/mL (B), 62.5 µg/mL (C), 125 µg/mL (D), 250 µg/mL (E), 500 µg/mL (F), and 1000 µg/mL (G) of the extract via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C. The existence of number (2) with the letters pointed the treatment by extract via SFE at operating temperature 50 °C.

Conclusion

The results of our experiments reflected the efficacy of SFE at operating temperature 30 °C for the extraction of MSK. Moreover, the obtained extract of MSK via SFE at operating temperature 30 °C contained several phenols and flavonoids which appeared in high concentrations as well as possess high biological activities including prevention of H. pylori, PC3 and SKOV3 cancer cell lines. Further explorations are required to searching for other active compounds and separating these compounds for the illness management.

Data availability

The results from the present investigation are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable appeal.

References

García-Mahecha, M. et al. Bioactive compounds in extracts from the Agro-industrial Waste of Mango. Molecules 28 (1), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010458 (2023).

Gupta, A. K. et al. A review on valorization of different byproducts of mango (Mangifera indica L.) for functional food and human health. Food Bioscience. 48, 101783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2022.101783 (2022).

Jahurul, M. H. A. et al. Mango (Mangifera indica L.) by-products and their valuable components: a review. Food Chem. 183, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.046 (2015).

Sadiea, R. Z. et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial potential of mango (Mangifera indica) seed kernels in Bangladesh. Front. Trop. Dis. 5, 1473494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2024.1473494 (2024).

Abdullah, A. S. H., Mohammed, A. S., Abdullah, R., Mirghani, M. E. S. & Al-Qubaisi, M. Cytotoxic effects of Mangifera indica L. kernel extract on human breast cancer (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines) and bioactive constituents in the crude extract. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 14, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-199 (2014).

Lim, K. J. A., Cabajar, A. A., Lobarbio, C. F. Y., Taboada, E. B. & Lacks, D. J. Extraction of bioactive compounds from mango (Mangifera indica L. var. Carabao) seed kernel with ethanol-water binary solvent systems. J. Food Sci. Technol. 56 (5), 2536–2544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-019-03732-7 (2019).

Qanash, H. et al. Anticancer, antioxidant, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of Kei Apple (Dovyalis caffra) Fruit. Sci. Rep. 12, 5914 (2022).

Cárdenas-Hernández, E. et al. From Agroindustrial Waste to nutraceuticals: potential of Mango seed for sustainable product development. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 104754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104754 (2024).

Yahya, R. et al. Molecular Docking and Efficacy of Aloe vera gel based on Chitosan Nanoparticles against Helicobacter pylori and its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Polymers 14, 2994 (2022).

Qanash, H. et al. Inhibitory potential of rutin and rutin nano-crystals against Helicobacter pylori, colon cancer, hemolysis and butyrylcholinesterase in vitro and in silico. Appl. Biol. Chem. 66, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-023-00832-z (2023).

Al-Rajhi, A. M. H. et al. Anti-Helicobacter Pylori, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and Anti-alzheimer’s activities of Laurel Leaf Extract treated by Moist Heat and Molecular Docking of its Flavonoid Constituent, Naringenin, against acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Life 13 (7), 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13071512 (2023a).

Bakri, M. M. et al. Impact of Moist Heat on Phytochemical Constituents, Anti-Helicobacter Pylori, Antioxidant, anti-diabetic, hemolytic and Healing Properties of Rosemary Plant Extract in Vitro. Waste Biomass Valor. 15, 4965–4979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-024-02490-8 (2024).

Al-Rajhi, A. M. H. & Abdelghany, T. M. In vitro repress of breast cancer by bio-product of edible Pleurotus ostreatus loaded with chitosan nanoparticles. Appl. Biol. Chem. 66, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-023-00788-0 (2023c).

Alghonaim, M. I., Alsalamah, S. A., Alsolami, A. & Abdelghany, T. A. Characterization and efficiency of Ganoderma lucidum biomass as an antimicrobial and anticancer agent. BioResources 18 (4), 8037–8061. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.18.4.8037-8061 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Ovarian cancer: diagnosis and treatment strategies. Oncol. Lett. 28 (3), 441. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2024.14574 (2024).

Baker, T. Early detection, symptoms, and Treatment options for Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Innovations. 10 (2), 332–343 (2024).

Almeeri, M. N. E., Awies, M. & Constantinou, C. Prostate Cancer, pathophysiology and recent developments in management: a narrative review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-024-01614-6 (2024).

James, N. D. et al. The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: planning for the surge in cases. Lancet 403 (10437), 1683–1722 (2024).

Seghosime, A., Ebeigbe, A. B. & Awudza, J. A. M. Potential use of Mangifera indica seed Kernel and Citrus Aurantifolia seed in Water Disinfection. Niger J. Technol. 36, 1303–1310. https://doi.org/10.4314/njt.v36i4.41 (2017).

Dorta, E., González, M., Lobo, M. G. & Laich, F. Antifungal activity of Mango Peel and seed extracts against clinically pathogenic and Food Spoilage yeasts. Nat. Prod. Res. 30, 2598–2604. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2015.1115995 (2016).

Qanash, H. et al. Ecofriendly extraction approach of Moringa peregrina biomass and their biological activities in vitro. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05916-4 (2024).

Almehayawi, M. S. et al. Evaluating the Anti-yeast, anti-diabetic, Wound Healing activities of Moringa oleifera extracted at different conditions of pressure via. Supercritical Fluid Extr. BioResources. 19 (3), 5961–5977. https://doi.org/ (2024).

Alsalamah, S. A. et al. Zygnema sp. as creator of copper oxide nanoparticles and their application in controlling of microbial growth and photo-catalytic degradation of dyes. Appl. Biol. Chem. 67, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-024-00891-w (2024).

Al-Rajhi, A. M. H., Qanash, H., Bazaid, A. S., Binsaleh, N. K. & Abdelghany, T. M. Pharmacological Evaluation of Acacia nilotica Flower Extract against Helicobacter pylori and Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma In Vitro and In Silico. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 14(4):237. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14040237

Abdelghany, T. M. et al. Antioxidant, Antitumor, Antimicrobial activities evaluation of Musa Paradisiaca L. Pseudostem Exudate cultivated in Saudi Arabia. BioNanoSci 9, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-018-0580-x (2019).

Rossignol, G. et al. Involvement of a phospholipase C in the hemolytic activity of a clinical strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. BMC Microbiol. 8, 189 (2008).

Abdelghany, T. M. et al. Effect of Thevetia peruviana seeds Extract for Microbial pathogens and Cancer Control. Int. J. Pharmacol. 17, 643–655 (2021).

da Silva, M. F. et al. Recovery of phenolic compounds of food concern from Arthrospira platensis by green extraction techniques. Algal Res. 25, 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2017.05.027 (2017).

Najim, T. M., Aldoori, A. A. & Hasan, M. S. Therapeutic effects of Mangifera indica extract against Proteus Mirabillis isolated from dogs with UTI, Invivo and invitro study. J. Surv. Fisheries Sci. 10 (3S), 3691–3697. https://doi.org/10.17762/sfs.v10i3S.1283 (2023).

Rajan, S., Thirunalasundari, T. & Jeeva, S. Anti—enteric bacterial activity and phytochemical analysis of the seed kernel extract of Mangifera indica Linnaeus against Shigella dysenteriae (Shiga, corrig.) Castellani and Chalmers. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 4 (4), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60089-8 (2011).

Mahmoud, M. F. et al. Pentagalloyl glucose, a major compound in mango seed kernel, exhibits distinct gastroprotective effects in indomethacin-induced gastropathy in rats via modulating the NO/eNOS/iNOS signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 800986. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.800986 (2022).

Pitchaon, M. Antioxidant capacity of extracts and fractions from mango (Mangifera indica Linn.) Seed kernels. Int. Food Res. J. 18 (2), 523–528 (2011).

Mutua, J. K., Imathiu, S. & Owino, W. Evaluation of the proximate composition, antioxidant potential, and antimicrobial activity of mango seed kernel extracts. Food Sci. Nutr. 5 (2), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.399 (2017).

Abdel-Aty, A. M., Salama, W. H., Hamed, M. B., Fahmy, A. S. & Mohamed, S. A. Phenolic-antioxidant capacity of mango seed kernels: therapeutic effect against viper venoms. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 28 (5), 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2018.06.008 (2018).

Buelvas-Puello, L. M. et al. Supercritical fluid extraction of Phenolic compounds from Mango (Mangifera indica L.) seed kernels and their application as an antioxidant in an Edible Oil. Molecules 26 (24), 7516. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247516 (2021).

Yap, K. M. et al. Mangifera indica (Mango): A promising medicinal plant for breast cancer therapy and understanding its potential mechanisms of action. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press). 13, 471–503. https://doi.org/10.2147/BCTT.S316667 (2021).

Yadav, A. et al. Effect of mango kernel seed starch-based active edible coating functionalized with lemongrass essential oil on the shelf-life of guava fruit. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods. 14 (3), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.15586/qas.v14i3.1094 (2022).

Zeng, Z. et al. Suppressive activities of mangiferin on human epithelial ovarian cancer. Phytomedicine 76, 153267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153267 (2020).

Katti, K. V. et al. Prostate tumor therapy advances in nuclear medicine: Green nanotechnology toward the design of tumor specific radioactive gold nanoparticles. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 318 (3), 1737–1747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-018-6320-4 (2018).

Ballesteros-Vivas, D., Alvarez-Rivera, G., Ocampo, A. F. G., Morantes, S. J., Camargo,A. D. P. S., Cifuentes, A., … Ibanez, E. (2019). Supercritical antisolvent fractionation as a tool for enhancing antiproliferative activity of mango seed kernel extracts against colon cancer cells.The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 152, 104563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2019.104563

Mahmoud, M. et al. Anticancer and antioxidant activities of ethanolic extract and semi-purified fractions from guava and mango seeds. Biomass Conv Bioref. 14, 20153–20169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04216-7 (2024).

Ríos, J. L., Giner, R. M., Marín, M. & Recio, M. C. A pharmacological update of ellagic acid. Planta Med. 84 (15), 1068–1093 (2018).

Shaban, N. Z. et al. Anticancer role of mango (Mangifera indica L.) peel and seed kernel extracts against 7,12- dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary carcinogenesis in female rats. Sci. Rep. 13, 7703. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34626-6 (2023).

Díaz-Gómez, R., López-Solís, R., Obreque-Slier, E. & Toledo-Araya, H. Comparative antibacterial effect of gallic acid and catechin against Helicobacter pylori. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 54 (2), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2013.07.012 (2013).

Kataria, R. & Khatkar, A. In-silico design, synthesis, ADMET studies and biological evaluation of novel derivatives of chlorogenic acid against urease protein and H. Pylori bacterium. BMC Chem. 13 (1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-019-0556-0 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis S.S., M.S.A., M.H.A., M.T.A.; investigation, F.A.A., M.S.W., D.A.B., N.N.A., W.A.O.,A.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing A.M.B., A.J.A., M.A.A., S.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Selim, S., Almuhayawi, M.S., Alruhaili, M.H. et al. Extraction of mango seed kernels via super fluid extraction and their anti-H. pylori, anti-ovarian and anti prostate cancer properties. Sci Rep 15, 6359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90346-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90346-z