Abstract

High-speed impact loading has a crucial effect on pore compaction and microscopic crack evolution for shale at different confining pressure (Pc). In this study, we selected the shales from Jiangxi (JX) and Sichuan Province (SC) in China, and then performed Split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) experiments at Pc = 0, 5, 15, and 25 MPa. Further, the impacted shales were tested by low temperature nitrogen adsorption (LTNA), mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) and environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM). The results showed that confining pressure could cause different degrees of pore compaction and crack blockage: total pore volume (TPV) based on MIP of the JX and SC shales at different confining pressures decreased by 24.3 ~ 69.2% and 54.1 ~ 66.5%, respectively; total pore volume based on LTNA decreased by 36.2 ~ 49.0% and 49.9 ~ 58.2%, respectively; total specific surface area (TSSA) based on BET model decreased 68.3 ~ 75.8% and 39.5 ~ 60.0%, respectively. It was found that the confining pressure had a more significant effect on macropores relative to mesopores. Confining pressure also changed the failure patterns of shales. The shales at low confining pressure (Pc = 0, 5, and 15 MPa) showed a marked characteristic of brittle shear damage. However, the shales at high confining pressure (Pc = 25 MPa) showed a brittle-ductile transition (BDT) phenomenon. Additionally, high confining pressure resulted in a tiny ductile damage and a significant increase in elastic modulus. Besides, the effect of different mineral compositions and grain sizes on crack extension was discussed. This study is meaningful for understanding and controlling pore compaction and crack extension, thus improving production processes of dynamic shale gas production technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

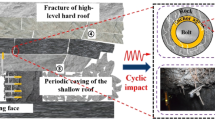

In recent years, with the increase in global energy demand and the growing problem of global warming, the total amount of shale gas extracted has increased dramatically. Shale gas is a clean and efficient energy source, and shale gas plays an important role in alleviating the energy challenge and the greenhouse effect1,2,3. Currently, the technology used for shale gas extraction is hydraulic fracturing. However, hydraulic fracturing technology exists a series of problems, such as serious waste of water resources, environmental pollution4, inapplicability to the exploitation of deep shale gas5. Therefore, some scholars proposed a new waterless fracturing technology, methane in-situ explosion fracturing (MISEF) technology6. The fracturing mechanism for this technique is illustrated in Fig. 1. Methane desorbed from the shale gas reservoir is mixed with the additive for combustion and ignited, then the shale is fractured by the combined effect of the combustion explosion shockwave and the explosive gases of high pressure7. Firstly, the explosion shockwave causes fragmentation and compaction of the shale in the area surrounding the blast hole8. Then the shockwave decays into a stress wave that continues to fracture the shale farther away from the blast hole. Finally, the fractures will continue to extend under the action of the explosive gas.

Combustion loading and SHPB loading are both high strain rate impact loading, so the fracturing effect of combustion loading can be studied by SHPB9. At present, scholars have conducted many studies on the failure patterns and mechanical properties of shale under SHPB loading. For example, Yang et al.10 reported that the dynamic crack initiation toughness was lower in Crack-divider and Crack-splitter loading modes. Crack-arrester loading mode would alter the extension direction of cracks. Luo et al.11 concluded that the dynamic mechanical characteristics of shale were affected by bedding angle. Shi et al.12 concluded that the fracture toughness has a positive relation with loading rate at a certain loading angle. However, these studies focus on the change rules of mechanical characteristics and analysis of macroscopic crack of shales under the impact. Fewer studies have been conducted on the microstructural change patterns of shale under high-speed impact loading. The mechanical property and the crack abundance are influenced by microstructure of shale13,14, including porosity, mineral composition15,16, grain shape17,18, grain size19,20, joint orientation21,22, water content23. For example, Huang et al.24 believed that the meso-mechanical anisotropy of shales was derived from the heterogeneous mineral component and micro-texture.

Additionally, with the upgrading of technology and equipment, shale gas extraction gradually moves from shallow layer to deep layer25,26. Deep shale reservoir has a high in-situ stress. In-situ pressure significantly affects the strength, deformation and damage patterns of deep shales27,28,29. In-situ stress also affects the fracturing effect of impact loading from two aspects: firstly, in-situ stress inhibits crack generation and extension during the fracturing process30; secondly, in-situ stress promotes crack closure after fracturing process31. However, the efficiency of shale gas extraction is directly related to the crack abundance of the shale gas reservoir after fracturing32.

Dynamic impact loading is effective at fracturing shales and creating penetrating cracks within the shale from a macroscopic perspective. However, there is still a lack of in-depth understanding of three aspects, including the effects of high-speed impact loading on pore structure of shales from a microscopic perspective, the effects of mineral grain composition and size on crack extension, and the failure mechanisms of the coupled loading of confining pressure and dynamic high-speed loading. Therefore, it is requisite to study the change rules of the pore structure and the crack extension under the coupling of confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\)) and high-speed impact loading. In this study, through the impact experiments of the JX and SC shales at different confining pressures, the pore compaction rules and the crack extension characteristics are revealed, which is meaningful for understanding and controlling pore compaction and crack extension, thus improving production processes of dynamic shale gas production technology.

Experiment

Geology setting

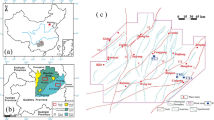

Shales were collected from outcrops from the Leping Formation in Jiangxi Province (JX) and the Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Province (SC), China. The Leping Formation is located Pingxiang-Leping Depression. This is one of the priority research targets for transitional shale gas reservoirs33. Organic carbon content is 0.21-23.24%, with an average of 1.74%. The vitrinite reflectance (\(\:{R}_{O}\)) is 0.7-4.06%, with an averaging average of 1.88%. The shale is in the mature-high mature stage, and the organic matter type of the shale is mainly type III34.The Longmaxi Formation shale is located in the Sichuan Basin. The Longmaxi Formation has become a leading target formation for shale gas exploration and development in China. Organic carbon content is 0.4-18.4%, with an average of 2.5%. The vitrinite reflectance (\(\:{R}_{O}\)) is 1.8-4.2%, with an averaging average of 1.88%. The shale is in the highly overmature stage, and the organic matter type of the shale is mainly type I35.

Sample preparation and mineral compositions

The shales were fabricated into cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 50 mm. The end face parallelism of specimens was maintained within \(\:\pm\:\)0.02 mm. The deviation from perpendicularity to the axis of the specimens was maintained within \(\:\pm\:\) 0.025 mm36. Additionally, an ultrasonic tester was used to test the longitudinal wave velocity of specimens before the experiment. Specimens with abnormal wave speeds were removed in order to avoid the influence of grown-in defects on the experimental results.

Quartz, feldspar, mica and carbonate minerals (calcite and dolomite) are common brittle minerals in shales. Kaolinite, montmorillonite, and illite are common clay minerals in shales21. The mineral compositions and contents of the two shales were measured by QEMSCAN. The results of the QEMSACN experiment of the JX and SC shales are shown in Fig. 2. The brittle mineral contents of the JX shales and SC shales are statistically 76.5% and 72.3%.

Moreover, brittleness index is one of the important characteristic parameters to evaluate the brittleness of shales. Calculating the contents of brittle minerals in shales is a typical method of brittleness index analysis37. The following formula can be achieved:

where \(\:{W}_{QFM}\) represents the total content of quartz, feldspar and mica minerals; \(\:{W}_{Calcite}\), \(\:{W}_{dolomite}\) and \(\:{W}_{Total}\) are the contents of calcite, dolomite and total minerals, respectively.

The brittleness indices of the JX shales and SC shales are 0.81 and 0.73, respectively. Apparently, the brittleness characteristics of the SC shales of the JX shales are essentially same, but the contents of specific brittle mineral compositions vary considerably.

Experimental systems and conditions

The SHPB loading is a high-speed dynamic impact loading, which can produce strong load changes and dynamic disturbances in the shale specimens within a very short period of time. At present, SHPB system can be used to study coupled dynamic impact tests with axial dynamic impact and confining pressure. It is widely accepted that SHPB system is the most successful loading technique for investigating the dynamic properties of rocks38.

The experimental system consists of two main sub-systems: an adjustable confining pressure device to simulate the state of high geopathic stress of shale gas reservoirs at different depths, and a SHPB impact system to simulate high-speed impact loading. The experimental system was used to study the pore compaction rules and crack evolution characteristics under the coupling of different confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\)) and SHPB loading. Additionally, two hypotheses must be used in this experiment, which are the one-dimensional elastic wave hypothesis and the specimen uniaxial uniform stress-strain hypothesis.

Before the experiment, the petroleum jelly lubricant was evenly smeared on the contact surface between the specimen and the impact bar to make the stress wave better transmitted. The dynamic impact experiments were conducted under room temperature conditions. The impact velocity was set to 10 m/s, the preloaded axial static loading to 2 MPa, and the confining pressures to 0, 5, 15, and 25 MPa, respectively.

Figure 3 illustrates the SHPB experimental system located at Henan University of Science and Technology39. The diameter of the system is 50 mm, and the length of the striker bar, incidence bar and transmission bar are 311 mm, 2000 mm and 2000 mm, respectively. Figure 3a shows the mechanism diagram of the SHPB system, including striker bar, incident bar, transmission bar, absorbing bar and buffer device, etc. Figure 3b demonstrates the mechanism diagram of the adjustable confining pressure device, including pressure gauge, steel frame, hydraulic oil inlet and outlet, sealing ring, rubber sleeve, etc. The device can apply a uniform confining pressure of 0–63 MPa to specimens. It can be observed from Fig. 3c that the SHPB system with the confining pressure device during the experiment.

Characterization experiments and conditions

An environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) and an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) were used to characterize the microcosmic crack morphology and connectivity of the impacted shale specimens. The FEI Quanta 250 ESEM could produce high-resolution images of microscopic cracks. Before the experiment, Ar-ion polisher was used to polish the specimens to make the surface smooth, which did not destroy the fine structure in pore and crack network compared to traditional polishing techniques.

An automated microporous physisorbent analyzer (AUTOSORB-IQ), which can measure pore sizes in the range 0.35–500 nm, was used to implement low-temperature nitrogen adsorption (LTNA) experiments. The specimens were milled into powder with a particle size of 40–60 mesh. Before the experiment, the specimens were also degassed at 110 °C for 12 h to protest moisture and impurity gases in the specimens from affecting the experimental results. The micropore volume, mesopore volume and pore surface area of shale specimens can be measured accurately by LTNA experiments and Density Functional Theory (DFT). DFT is applicable to the pore size ranging from 0.35 nm to 100 nm. It can accurately describe full-size pore characterization ranging from the micropore to mesopore of shales40,41.

An automatic mercury porosimeter (POREMASTER60GT), which can measure pore sizes in the range of 3–950,000 nm, was used to conduct mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) experiments. The specimens were milled into powder with a particle size of 60–80 mesh. Before the experiment, the specimens were also degassed at 110 °C for 12 h. The macropore volume of shale specimens can be measured accurately by MIP experiments and Washburn equation42.

Results

Dynamic failure patterns

The macroscopic failure patterns of the JX and SC shales after impact at different confining pressures (\(\:{P}_{c}\)) is displayed in Fig. 4. It can be found that the confining pressure obviously changes the macroscopic damage patterns of the shales after impact43. The JX and SC shales underwent brittle fracture damage or cleavage fracture along bedding planes without confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0 MPa)11. Similarly, the two shales showed obvious shear damage characteristics at low confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, and 15 MPa), and the surface of the specimens appeared obvious cracks. Moreover, the two shales remained basically intact after impact at high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa), but stress concentration may cause localized damage on the surface. These phenomena suggested that confining pressure inhibited the fracturing effect of high-velocity impact loading and attenuated the dynamic changes in the shales.

Microscopic crack characteristics

In this paper, we studied the microscopic crack evolution patterns of the JX and SC shales after impact at different confining pressures by means of ESEM and EDS. EDS can distinguish mineral composition but has a limited resolution, and ESEM has a high resolution but can only determine mineral composition based on gray scale values. Through the combination of ESEM and EDS, we can distinguish the mineral components on the microscopic perspective and study the influence mechanism of components on the microscopic crack evolution. To name a few examples here, quartz is silicon dioxide, and the main constituent elements are Si and O; it is characterized in ESEM images as circular or elliptical, with an uneven surface and low brightness. Albite, an aluminosilicate mineral with a major elemental composition of Na, O, Al and Si, is intercalated with quartz mineral grains; it is also characterized in ESEM images as circular or elliptical, but occasionally contains dissolution holes and is brighter than quartz. Calcite, a carbonate mineral with a major elemental composition of Ca, C and O, has a regular shape and a similar color with quartz in ESEM images, and often develops dissolution pores. Subsequently, clay minerals including kaolinite, illite, anthophyllite, chlorite, etc. are layered silicate minerals that appear filamentous, scaly, or irregular; they are slightly brighter than quartz, and its main constituent elements are Ca, Na, K, O, Al and Si44. It should be emphasized that chlorite and illite are the main clay minerals in JX shales and SC shales. Chlorite is a layered silicate mineral containing Mg and Fe. Illite is rich in K and Al, and lacks Fe, which help us to recognize it more easily from images of ESEM and EDS. Besides, we can easily distinguish between natural cracks and impact cracks, because impact cracks are not filled with minerals and show up as black in the EDS images.

Figure 5 depicts the microscopic cracks of the JX shale specimens at different confining pressure conditions. Parts of the natural cracks continued to extend into new cracks as illustrated in Fig. 5a,d,e,g,h. Other natural cracks were compacted and filled after impact as reflected in Fig. 5b,c. The JX shale specimens after impact showed a severe crack blockage phenomenon and a poor microscopic crack development. Overall, the JX specimens appears to be unsuitable for shale gas extraction.

Figure 6 presents the microscopic cracks of the SC shale specimens at different confining pressure conditions. The SC shales has a high content of quartz. The main quartz types are extrabasinal detrital granular quartz (5 ~ 35 μm) and microcrystalline quartz (2 ~ 5 μm). Microcrystalline quartz distributed randomly is favorable to attenuate compaction effect and promote extension of microscopic crack. Granular quartz of SC shale specimens mainly extended pericrystalline cracks and intergranular cracks. In addition, the mixed layer of albite and illite developed a large number of micro-cracks after impact. Calcite inhibits extension of intergranular crack as shown in Fig. 6f,h. As the crack develops near the calcite, the width of crack was significantly reduced.

Microscopic pores characterization

The pore classification method used in this paper was proposed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), classifying pores into micropores (< 2 nm), mesopores (2 ~ 50 nm) and macropores (> 50 nm).

LTNA results

As shown in Fig. 7, the adsorption and desorption curves of the untreated the JX shale showed a narrower hysteresis loop (P/P0 = 0.45 ~ 1.0) and an inflection point (P/P0 = 0.5). The hysteresis loop is an H2 type45, indicating that pores with smaller sizes (d < 5 nm) mainly develop slit pores, ink-bottle pores, or semi-closed pores. Then the adsorption curve rises rapidly at P/P0 between 0.9 and 1.0, indicating that the mesopores are completely open pores with a better pore connectivity, such as cylindrical pores open on all sides or parallel plate pores46. Similarly, the hysteresis ring and inflection point of the impacted the JX shales almost disappear, and the type of hysteresis loop is H3 type. This phenomenon indicates that the micropores and mesopores of the impacted the JX shales are mainly open pores with good connectivity, such as parallel plate pores or cylindrical pores47. In addition, the total adsorbed quantity of the JX shales decrease significantly after impact at different confining pressures, indicating that some of the pores and cracks were compacted. Overall, the adsorption curves basically overlap after the impact at different confining pressures, indicating that confining pressure has relatively small effect on compaction is minor for the JX shales.

For the SC shales, the hysteresis loops of both the untreated and impacted SC shales are of the H2 type, with significant inflection points (P/P0 = 0.5), suggesting that the pores morphology with a smaller size (d < 5 nm) includes ink slit pores, ink bottle pores, or semi-closed pores. Similarly, at P/P0 between 0.9 and 1.0, the adsorption curve rises rapidly, demonstrating that the number of open pores is relatively large.

As shown in Table 1, based on the LTNA method, the total pore volume and total specific surface area of the JX and SC shales decreased significantly after impact of different confining pressures. The total pore volume (TPV) of the JX and SC shales decreased 36.2 ~ 49.0% and 49.9 ~ 58.2%, and the total specific surface area (TSSA) decreased 68.3 ~ 75.8% and 39.5 ~ 60%, respectively. The total specific surface area of shales is mainly contributed by micropores and mesopores. Therefore, the specific surface area of the SC shales is larger after impact.

Figure 8 depicts the distribution of pores with different sizes of the two shales. The changes in the total pore volume of the JX shales were mainly due to changes in mesopores and pores with a size of 75 nm. The changes in total pore volume of the SC shales were due to changes in pores of all sizes. Figure 9 reflects the specific surface area distribution of the two shales. The changes in specific surface area of the JX shales were primarily due to changes in mesopores below 30 nm. The changes in specific surface area of the SC shales were due to changes in pores of all sizes.

MIP results

Previous studies have shown that the internal pores of shales may be affected by the high pressure of mercury feed, leading to collapse and destruction of pores. This phenomenon causes inaccuracies in the experiments. Therefore, we investigated only the pore characteristics of macropore by MIP. Figure 10 illustrates the Hg-intrusion curves, Hg-extrusion curves and pore size distributions of the JX and SC shales. Significant hysteresis loops are present in both the untreated the JX and SC shales, suggesting that there are a large number of open pores appeared and a relatively excellent pore connectivity. After the high-speed impact, the hysteresis loops and the total mercury intrusion volume of the two shales became smaller, and the Hg-intrusion and Hg-extrusion curves of the high-pressure portion is nearly overlapped. The phenomena reflect the compaction and collapse of the pores and pore throats of the shales under the high-speed impact. It results in the emergence of numerous closed or semi-closed pores and poor pore connectivity.

As indicated in Fig. 11, with the increase of confining pressure, the total pore volume and macropore pore volume of the two shales show a tendency of decreasing firstly and then increasing, but total decreasing. It indicates that low confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 5, and 15 MPa) increases the stress density and enhances the compaction effect, leading to blockage, compaction and destruction of pores. However, too high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa) inhibits the compaction effect.

Combined analysis by MIP and LTNA

As illustrated in Fig. 12, the impact at different confining pressures (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, 15, and 25 MPa) resulted in compaction with different degrees of mesopores and macropores of the two shales. At low confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 5, and 15 MPa), there are a marked increase in the proportion of mesopores and a significant decrease in the proportion of macropores. At high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa), the JX shales and SC shales have larger volume and proportion of macropores after impact compared to low confining pressure.

Additionally, all micropores of the JX shales disappeared after impact at different confining pressure conditions, whereas the volume of micropores of the SC shales became larger after impacts at low confining pressure conditions, indicating that high-velocity impacts at certain confining pressures strengthened the connectivity of micropores for SC shales.

Meanwhile, we found that the sensitivity of mesopores to the compaction effect is different from that of macropores to the compaction effect at different confining pressure conditions. After impact at different confining pressures, the mesopore volume of the JX and SC shales changed tiny, indicating that the compaction effect on mesopores is not related to the confining pressure but only to the nature of shales themselves. At different confining pressure conditions, changes in total pore volume are mainly influenced by changes in macropore volume. Therefore, the trend in changes of macropore volume is the same as that of total pore volume.

Discussion

The extensive characteristics of dynamic impact cracks are jointly influenced by conditions, such as confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\)), components, mineral grain sizes, etc. Through pore characterization experiments and ESEM experiments, we have derived the change rules of the pores and cracks of the two shales after impact. However, the influence factors and mechanisms of microscopic structures of shales needs further study.

Fractal dimension of shale pores

The fractal dimension (\(\:D\)) is widely used to characterize the roughness of pore surface and the complexity of pore structure about porous media48. Currently, the Menger model is the most widely used fractal dimension calculation model based on MIP. Equation (2)49 presents the calculation of the fractal dimension (\(\:{D}_{M}\)) based on MIP:

where \(\:{V}_{M}\) is the volume of injection mercury, cc/g; \(\:{P}_{M}\) presents the pressure of injection mercury, MPa; \(\:D\)M depicts the fractal dimension based on MIP. Previous studies have shown that there is no linear relationship between the data in high pressure due to the damage of pores caused by high pressure mercury50. Therefore, we selected only the data from the low-pressure region for data fitting. Figure 13 shows the fitted plot of the MIP data based on the Menger model, and \(\:D\)M can be derived from the slope of the fitted straight line. Obviously, the fractal curves show a good linear relationship in the low-pressure region.

The Frenkel-Halsey-Hill (FHH) model51 is the most efficient calculation model of fractal dimension based on LTNA. Equation (3) presents the calculation of the fractal dimension (\(\:{D}_{L}\)) based on LTNA:

where \(\:{P}_{L}\) is the gas equilibrium pressure, MPa; \(\:{V}_{L}\) depicts the adsorbed volume of nitrogen at equilibrium pressure \(\:{P}_{L}\), cc/g; PL0 presents the saturation vapor pressure of nitrogen, MPa; \(\:D\)L is the fractal dimension based on LTNA. Previous studies have shown that there is a cutoff point at p/p0 = 0.48 that can divide the FHH fitted straight line into two stages. The fractal dimension \(\:{D}_{L1}\) calculated in the first stage (0 < p/p0 < 0.48) reflects the roughness of pore surface. The fractal dimension \(\:{D}_{L2}\) calculated in the second stage (0.48 < p/p0 < 1) reflects the complexity of pore structure52. The fitted plots of the LTNA data based on the FHH model are illustrated in Fig. 14. \(\:D\)L1 and \(\:D\)L2 can be derived from the slope of the fitted straight lines.

Table 2 lists the fractal dimensions of the JX and SC shales based on the MIP and LTNA. All fitted curves have a high correlation coefficient (\(\:{R}^{2}>\:\)0.958), indicating that the pores have a strong fractal characteristic. It can be noticed that the pore structure of micropore and mesopore is relatively simple, while the pore structure of macropore is more complex.

Figure 15 reflects the trend of the fractal dimension with confining pressure. The \(\:D\)M of impacted the JX shales at different confining pressures is 2.678 ~ 2.778, and the \(\:D\)M of the SC shales is 2.523 ~ 2.759. The trend of fractal dimension is similar for both the two shales. In particular, the \(\:D\)M becomes smaller with increasing confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, and 15 MPa), indicating that the complexity of macropore decreases. Moreover, the complexity of macropores is approximately bigger at high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa) and no confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0 MPa). Changes in the values indicate increased complexity and improved heterogeneity of pore structure. This result also verifies that low confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 5, and 15 MPa) enhances the effect of compaction on the macropore. Ultimately, it makes the macropore less complex. In contrast, the high confining pressure increased the compressive strength of shales, inhibiting the compaction and collapse of the macropore.

The \(\:D\)L1 of impacted the JX shales at different confining pressures is 1.928 ~ 2.394, and the \(\:D\)L1 of the SC shales is 2.322 ~ 2.446. The \(\:D\)L1 reflects a decrease of the number of micropores, resulting in a more regular and flat pore surface53. The \(\:D\)L2 of impacted the JX shales at different confining pressures is 2.422 ~ 2.586, and the \(\:D\)L2 of the SC shales is 2.429 ~ 2.679. The values of the \(\:D\)L2 are approximately equal at \(\:Pc\) = 0, 5, 15, and 25 MPa, justifying that the confining pressure has less influence on the compaction of the mesopores. The variation in fractal dimension is mainly due to the difference in the damage degree, and the confining pressure is the main factor affecting the damage degree. Confining pressure increases the compactness and the bonding strength between mineral grains54, which reduces the ability of cracks to expand and improves compaction under impact.

Effects of mineral characteristics on microscopic cracks

The contents of total brittle minerals and total clay minerals of the JX and SC shales are similar, but the two shales show large differences in the results of ESEM experiments. This is due to the discrepancies of mineral characteristics. Shale can be thought as a layered rock consisting of a random distribution of brittle mineral grains and clay grains. The effect of mineral characteristics on crack was studied based on this definition. The specific brittle minerals affect the cracks with different mechanisms. In addition, the sizes of mineral grain greatly influence crack extension. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effects of mineral characteristics on the crack structure of shales.

Mineral compositions

The composition of shale mineral can determine the gas content, the pore structure, and the extension characteristics of natural and impact cracks in shale gas reservoirs. Thus, production patterns and efficiencies of shale gas are influenced by the specific mineral compositions of shales. Combining the common mineral compositions and the statistical results in Fig. 2, we mainly discussed the effects of brittle minerals (quartz, calcite, feldspar, and pyrite) and clay minerals (illite) on the crack structure of the shales.

Quartz has a significant effect on the properties of shales55. On the one hand, the randomly distributed quartz interconnects other brittle mineral grains to act as a rigid framework to resist compaction in the process of impact and protect the pores from destruction56. On the other hand, the compaction stress can transmit along the rigid framework to improve the energy absorption rate of shales57. The quartz contents of the JX and SC shales are 32.63% and 49.82%, respectively. As shown in Figs. 5 and 6, the SC shales have a higher number of cracks and a greater crack width at the same conditions. Calcite is a typical carbonate mineral with distinctive banding characteristics58. Carbonate minerals produce significant cementation and fill pores and cracks, affecting the connectivity of the shales59. The calcite contents of the JX and SC shales are 23.06% and 0.03%, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5 (a), (d), (e), (g) and (h), most of the cracks of the JX shales are clearly filled with calcite minerals, reducing the impact fracturing effect. Main cracks have tended to form in weak mineral bands, such as calcite bands or clay mineral bands60. Albite is the main feldspar mineral in the JX and SC shales, and the contents are 8.25% and 13.92%, respectively. Feldspar acts similarly to quartz which can strengthen the ability to resist compaction of shales. Illite is the main clay mineral in the JX and SC shales, and the contents are 8% and 17.15%, respectively. Micropores and microcracks are often massively extended in clay minerals around brittle mineral grains. In addition, micropores and microcracks can easily continue to extend into main cracks after impact61, which provides efficient transportation channels for shale gas.

Shales with higher content of brittle mineral can produce more cracks after fracturing operations, which is beneficial for shale gas extraction. In terms of shales with higher content of clay mineral, micropores and microcracks are more developed, providing conditions and space for the extension of cracks and the transportation of shale gas. Therefore, higher content of brittle mineral or clay mineral will not always favor shale gas exploitation, but rather a relatively suitable ratio.

Mineral grain sizes

The size of mineral grain is one of the main microscopic factors that control characterization of crack. In fact, the size of mineral grain has a little effect on the germination of new cracks, but it clearly controls the extension of intergranular cracks14 and the number of microcracks. The larger size of brittle grain also leads to a larger tortuousness and width of the main cracks20. The size distribution of grains about the main minerals in the JX and SC shales is shown in Figs. 16 and 17. Albite (Fel) and illite (Cl) have a smaller average size of mineral grain. As shown in the elliptical region of Figs. 5 and 6, microcracks occurred abundantly in the mixing bands of the two minerals.

Therefore, the mechanism of mineral components and particle sizes for crack is summarized. Specifically, smaller mineral particles provide space for microcrack generation and extension due to their greater number and small grain boundaries. Lager grain size leads to a wider grain boundary, which will increase the width of main cracks. As illustrated in Fig. 18a, Locations with smaller grain sizes will have a large number of microcracks. Similarly, large brittle mineral grains dominate the extension paths and the width of the main cracks as reflected in Fig. 18b.

Effects of loading on microscopic cracks under confining pressures

The dynamic modulus of elasticity of shales at different confining pressure conditions is shown in Fig. 19. For the JX and SC shales, the differences of the elastic modulus are small for impacts at \(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, and 15 MPa, and both shales tend to brittle shear damage. However, the elastic modulus and toughness of the two shales are greatly increased at high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa). In fact, the result is due to the BDT (brittle-to-ductile transition) phenomenon43 that occurs in shales at high confining pressure. Specifically, the shales are able to produce significant macroscopic cracks at lower strain rates and confining pressure. However, when the confining pressure exceeds about 20 MPa, the shales require extremely high strain rates to produce the same cracks. High confining pressure substantially strengthen ability to withstand a larger strain and resist compaction. This also explains the previous experimental result that the pore compaction phenomenon is more significant at low confining pressure compared to high confining pressure.

Overall, the pattern of cracks extension of shales is significantly different at different confining pressures, and the pattern is shown in Fig. 18 (e). Confining pressure inhibits crack generation and extension. Shales at no confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0 MPa) tend to occur brittle damage. At low confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) =5, and 15 MPa), the confining pressure suppresses the dynamic changes in the circumferential direction. The shales tend to occur shear damage, and most of the cracks are shear cracks. At high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa), the shales are transformed from brittle to ductile, which improves the ability of shale to withstand stress62. The shales occur a ductile damage and remain largely intact.

Mode of compaction and blockage

High-speed shock wave first acted on the wall surface of shale to generate compressive stress, resulting in compression damage to the shale. During this process, the pores and cracks within the shale were compacted to varying degrees. The shock wave then decays into a stress wave that continues to act on the rock. When the stress wave passes through the pore, the reflection and scattering of the stress wave will occur, resulting in the phenomenon of stress concentration63. Obviously, macropores are more sensitive to stress concentration phenomena compared to mesopores and micropores. This phenomenon also explains the experimental results. Additionally, this phenomenon can lead to pore collapse and crack generation, but it can also lead to the fragmentation of brittle mineral particles, which can lead to pore blockage. In summary, the mode of compaction and blockage is summarized in Fig. 18.

As shown in Fig. 18 (a) (b), shale is viewed as a granular mineral composed of brittle mineral grains interacting with clay mineral grains. Brittle mineral particles are connected to each other to form a rigid framework which can resist the compaction. Impact cracks are often extended on weak surfaces (clay mineral bands) between brittle mineral grains. In addition, high velocity impact leads to pore compaction and crack blockage from two aspects. Firstly, as shown in Fig. 18 (c), impacts can compress clay minerals, and decrease the width of main cracks. They cause pore compaction and crack blockage. Secondly, as indicated in Fig. 18 (d), brittle mineral grains in the process of impact produce tiny rock grains that can block the cracks. Finally, they result in reduced crack connectivity.

In order to avoid the effects of compaction and to utilize the energy primarily for crack extension, directional blasting should be achieved through the use of appropriately sized slotted tubes64.

Conclusions

In this study, JX and SC shales were used to explore the effects of high-speed impact loading on characteristics of pore structure, crack evolution and fractal dimension at different confining pressures (\(\:{P}_{c}\)). The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Confining pressure significantly affects the dynamic failure pattern. The shales tend to occur shear fracture at low confining pressures (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, and 15 MPa). Additionally, the shales at high confining pressure (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa) show the BDT (brittle-to-ductile transition) phenomenon and a tiny ductile failure, but remain generally intact.

(2) High-speed impact loading can compact both micro-, meso- and macro- pores. Total pore volume (TPV) based on MIP of the JX and SC shales at different confining pressures (\(\:{P}_{c}\) = 0, 5, 15, and 25 MPa) decreased by 24.3 ~ 69.2% and 54.1 ~ 66.5%, respectively; total pore volume based on LTNA decreased by 36.2 ~ 49.0% and 49.9 ~ 58.2%, respectively. At \(\:{P}_{c}\) = 25 MPa, confining pressures inhibits compaction.

(3) Mesopores and macropores of the shales have a different sensitivity to pore compaction under high-speed impact loading and confining pressures. The compaction on mesopores is less affected by confining pressure. The changes in total pore volume under high-speed impact loading are mainly governed by the variations in macropore volume.

(4) Impact loading leads to the reduce in crack volume and connectivity explained by two aspects: compress clay minerals; tiny brittle grains produced by impact block the cracks. The size of mineral grain has a little effect on the germination of cracks and a significant effect on extension cracks. Specifically, mineral grains with high size determine the extension direction of main crack, and mineral grains with small size determine the number of microcracks.

Data availability

The data supporting the outcomes of this study are available based on the request from the corresponding author.

References

Middleton, R. S., Gupta, R., Hyman, J. D. & Viswanathan, H. S. The shale gas revolution: barriers, sustainability, and emerging opportunities. Appl. Energy. 199, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.04.034 (2017).

Yang, Y., Wang, L., Fang, Y. & Mou, C. Integrated value of shale gas development: a comparative analysis in the United States and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 76, 1465–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.174 (2017).

Yuan, J., Luo, D. & Feng, L. A review of the technical and economic evaluation techniques for shale gas development. Appl. Energy. 148, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.03.040 (2015).

Vengosh, A., Warner, N., Jackson, R. & Darrah, T. The effects of Shale Gas Exploration and Hydraulic Fracturing on the quality of Water resources in the United States. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 7, 863–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeps.2013.03.213 (2013).

Wang, C., Wang, F., Du, H. & Zhang, X. Is China really ready for shale gas revolution—re-evaluating shale gas challenges. Environ. Sci. Policy. 39, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.02.007 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Experimental Investigation of Methane Explosion-Induced fracture propagation and load characteristics within Reservoir Perforation. Energy Fuels. 38, 16398–16415. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c02935 (2024).

Changyou, L., Jingxuan, Y. & Bin, Y. Rock-breaking mechanism and experimental analysis of confined blasting of borehole surrounding rock. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27, 795–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.07.016 (2017).

Lan, R. et al. Damage and fragmentation of Rock under Multi-long-hole blasting with large empty holes. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57, 7603–7622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03942-2 (2024).

Yao, W. & Xia, K. Dynamic notched semi-circle bend (NSCB) method for measuring fracture properties of rocks: fundamentals and applications. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 11, 1066–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2019.03.003 (2019).

Yang, G., Li, X., Bi, J. & Cheng, S. Dynamic Crack initiation toughness of Shale under Impact Loading. Energies 12, 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12091636 (2019).

Luo, N., Fan, X., Cao, X., Zhai, C. & Han, T. Dynamic mechanical properties and constitutive model of shale with different bedding under triaxial impact test. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 216, 110758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110758 (2022).

Shi, X. et al. Experimental study of the dynamic fracture toughness of anisotropic black shale using notched semi-circular bend specimens. Eng. Fract. Mech. 205, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.11.027 (2019).

Yu, H. et al. The rock mechanical properties of lacustrine shales: Argillaceous shales versus silty laminae shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 141, 105707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105707 (2022).

Eberhardt, E., Stimpson, B. & Stead, D. Effects of Grain size on the initiation and propagation thresholds of stress-induced brittle fractures. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 32, 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s006030050026 (1999).

Luo, J. et al. Effects of Mineral Composition and Lamina on Mechanical properties and fractures of the wufeng–Longmaxi Shale in the Luzhou Area of the Southern Sichuan Basin. Energy Fuels. 37, 13949–13959. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c02594 (2023).

Patel, R. et al. Microstructural and mechanical property characterization of Argillaceous, Kerogen-rich, and Bituminous Shale rocks. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 108, 104827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2022.104827 (2022).

Huang, Q., Zhou, X. & Liu, B. Effect of realistic shape on grain crushing for rounded and angular granular materials. Comput. Geotech. 162, 105659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105659 (2023).

Cox, M. R. & Budhu, M. A practical approach to grain shape quantification. Eng. Geol. 96, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2007.05.005 (2008).

Přikryl, R. Some microstructural aspects of strength variation in rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 671–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(01)00031-4 (2001).

Gao, W., Iqbal, J., Xu, D., Sui, H. & Hu, R. Effect of brittle Mineral size on hydraulic fracture propagation in Shale Gas Reservoir. Geofluids e9147048. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9147048 (2019).

Wei, J. et al. Influence of shale bedding on development of microscale pores and fractures. Energy 282, 128844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128844 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Study on the effects of joints orientation and strength on failure behavior in shale specimen under impact loads. Int. J. Impact Eng. 163, 104162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104162 (2022).

Wang, J., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Chang, T. & Jiang, Q. Effects of Bedding geometry and Cementation Strength on Shale Tensile Strength based on discrete element Method. Shock Vib. 2021, 7805617. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7805617 (2021).

Huang, B., Li, L., Tan, Y., Hu, R. & Li, X. Investigating the Meso-Mechanical Anisotropy and Fracture Surface Roughness of Continental Shale. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 125. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017828 (2020).

Ma, X., Xie, J., Yong, R. & Zhu, Y. Geological characteristics and high production control factors of shale gas reservoirs in Silurian Longmaxi Formation, southern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47, 901–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1876-3804(20)60105-7 (2020).

He, Z. et al. Geological problems in the effective development of deep shale gas: a case study of Upper Ordovician Wufeng-Lower Silurian Longmaxi formations in Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Shiyou Xuebao/Acta Petrolei Sinica. 41, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.7623/syxb202004001 (2020).

Mechanical behavior and constitutive model of shale under. real-time high temperature and high stress conditions | Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology n.d. accessed June 6, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-022-01580-4.

Li, Y. Mechanics and fracturing techniques of deep shale from the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Energy Geoscience. 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engeos.2020.06.002 (2021).

Mohamadi, M. & Wan, R. G. Strength and post-peak response of Colorado shale at high pressure and temperature. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 84, 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2015.12.012 (2016).

Nie, H. et al. Deep shale gas in the ordovician-silurian wufeng–longmaxi formations of the Sichuan Basin, SW China: insights from reservoir characteristics, preservation conditions and development strategies. J. Asian Earth Sci. 244, 105521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2022.105521 (2023).

Yi, C., Johansson, D. & Greberg, J. Effects of in-situ stresses on the fracturing of rock by blasting. Comput. Geotech. 104, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2017.12.004 (2018).

Zhao, Z., Zheng, Y., Zeng, B. & Song, Y. Investigation and application of High-Efficiency Network Fracturing Technology for Deep Shale Gas in the Southern Sichuan Basin. ACS Omega. 7, 14276–14282. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c01060 (2022).

Liu, J., Lu, D. & Li, P. Nano-scale dual-pore-shape structure and fractal characteristics of transitional facies shale matrix. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 68, 102907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2019.102907 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. Pressure–temperature–time–composition (P–T–t–x) of paleo–fluid in Permian organic–rich shale of Lower Yangtze platform, China: insights from fluid inclusions in fracture cements. Mar. Pet. Geol. 126, 104936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.104936 (2021).

Dai, J. et al. Geochemistry of the extremely high thermal maturity Longmaxi Shale gas, southern Sichuan Basin. Org. Geochem. 74, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2014.01.018 (2014).

Zhou, Y. X. et al. Suggested methods for determining the dynamic strength parameters and mode-I fracture toughness of rock materials. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 49, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2011.10.004 (2012).

Jin, X., Shah, S., Roegiers, J-C. & Zhang Fracability evaluation in Shale reservoirs - An Integrated Petrophysics and Geomechanics Approach. SPE J. 20. https://doi.org/10.2118/168589-MS (2014).

Zhang, Q. B. & Zhao, J. A review of dynamic experimental techniques and mechanical Behaviour of Rock materials. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 47, 1411–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-013-0463-y (2014).

Ma, C., Zhu, C., Zhou, J., Ren, J. & Yu, Q. Dynamic response and failure characteristics of combined rocks under confining pressure. Sci. Rep. 12, 12187. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16299-9 (2022).

Klimakow, M., Klobes, P., Rademann, K. & Emmerling, F. Characterization of mechanochemically synthesized MOFs. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 154, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.11.039 (2012).

Li, J. et al. A comparison of experimental methods for describing shale pore features — a case study in the Bohai Bay Basin of eastern China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 152, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2015.10.009 (2015).

Arismendi Florez, J. J., Ferrari, J. V. & Ulsen, C. Study of the contact angle and roughness effects on mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) analysis in natural/real carbonate rocks using massive pure minerals and synthetic carbonate rocks. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 32, 286–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.07.177 (2024).

Cheng, G. et al. Experimental study on brittle-to-ductile transition mechanism of lower silurian organic-rich shale in south China. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105543 (2023).

Gao, Z., Liang, Z., Qinhong, H., Jiang, Z. & Xuan, Q. A new and integrated imaging and compositional method to investigate the contributions of organic matter and inorganic minerals to the pore spaces of lacustrine shale in China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 127, 104962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.104962 (2021).

Donohue, M. D. & Aranovich, G. L. Adsorption Hysteresis in porous solids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 205, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcis.1998.5639 (1998).

Liu, H. et al. Synthetical study on the difference and reason for the pore structure of the 3 coal reservoir from the southern Qinshui Basin, China, using mercury intrusion porosimetry, low-temperature N2 adsorption, low field nuclear magnetic resonance, and nuclear magnetic resonance cryoporometry. Energy Rep. 6, 1876–1887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.07.011 (2020).

Li, Z., Liu, D., Cai, Y., Wang, Y. & Teng, J. Adsorption pore structure and its fractal characteristics of coals by N2 adsorption/desorption and FESEM image analyses. Fuel 257, 116031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116031 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Micro-nano scale pore structure and fractal dimension of ultra-high performance cementitious composites modified with nanofillers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 141, 105129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105129 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Pore changes of slickwater-containing shale under supercritical CO2 treatment. Fuel 312, 122775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122775 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of CO2 intrusion on pore structure characteristics of mineral-bearing coal: implication for CO2 injection pressure. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 108, 104808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2022.104808 (2022).

Zhang, S., Tang, S., Tang, D., Huang, W. & Pan, Z. Determining fractal dimensions of coal pores by FHH model: problems and effects. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 21, 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2014.10.018 (2014).

Zhou, L. & Kang, Z. Fractal characterization of pores in shales using NMR: a case study from the Lower Cambrian Niutitang formation in the Middle Yangtze Platform, Southwest China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 35, 860–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.09.030 (2016).

Su, E., Liang, Y. & Zou, Q. Structures and fractal characteristics of pores in long-flame coal after cyclical supercritical CO2 treatment. Fuel 286, 119305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119305 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Tailoring Anti-impact properties of Ultra-high performance concrete by incorporating Functionalized Carbon nanotubes. Engineering 18, 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.04.030 (2022).

Liu, B., Schieber, J., Mastalerz, M. & Teng, J. Variability of rock mechanical properties in the sequence stratigraphic context of the Upper Devonian New Albany Shale, Illinois Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 112, 104068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104068 (2020).

Qiu, Z. et al. Silica diagenesis in the lower paleozoic wufeng and Longmaxi Formations in the Sichuan Basin, South China: implications for reservoir properties and paleoproductivity. Mar. Pet. Geol. 121, 104594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104594 (2020).

Ye, Y., Tang, S., Xi, Z., Jiang, D. & Duan, Y. Quartz types in the Wufeng-Longmaxi formations in southern China: implications for porosity evolution and shale brittleness. Mar. Pet. Geol. 137, 105479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.105479 (2022).

Li, Y., Wang, B., Xue, L., Liu, S. & Wang, T. Shale mineral particles directional arrangement and its effect on the mesoscopic failure mechanism. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03513-9 (2024).

Zheng, Y., Liao, Y., Wang, Y., Xiong, Y. & Peng, P. The main geological factors controlling the Wufeng-Longmaxi shale gas content. Bulletin 106, 2073–2102. https://doi.org/10.1306/07132218243 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. The Mechanical properties and fracture characteristics of Shale layered samples from the Lucaogou formation considering Natural Crack and Mineral distribution. Materials 16, 5881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16175881 (2023).

Song, H. et al. In-situ SEM study of fatigue micro-crack initiation and propagation behavior in pre-corroded AA7075-T7651. Int. J. Fat. 137, 105655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2020.105655 (2020).

Mechanical properties of. graphene-reinforced reactive powder concrete at different strain rates | Journal of Materials Science n.d. accessed December 16, (2024). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10853-019-04246-5.

Tao, M., Ma, A., Cao, W., Li, X. & Gong, F. Dynamic response of pre-stressed rock with a circular cavity subject to transient loading. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 99, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2017.09.003 (2017).

Li, Y., Huang, C., Liu, L., Chen, X. & Zhao, Q. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the explosive characteristics of slotted cartridges under different slotted structures. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 54, 6173–6189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-021-02592-y (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant Number: 2020YFA0711803), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Number: 52174211, 52334007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiawei Wang: Investigation, Writing–original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization. Chuanjie Zhu: Writing–review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Cong Ma: Writing–review & editing, Supervision. Zhongqiu Liang: Writing–review & editing, Supervision. Ke Li: Investigation. Cheng Zhai: Investigation. Baiquan Lin: Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhu, C., Ma, C. et al. Pore compaction and crack evolution of shale rock under high-speed impact loading and different confining pressures. Sci Rep 15, 6511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90347-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90347-y